Controlling Administrative Discretion Promotes Social Equity? Evidence from a Natural Experiment

Related Content: Granados (PAR January/February 2017)

Abstract

Although social equity has been a formal pillar of public administration for decades, identifying mechanisms through which public officials inadvertently reproduce unfair conditions remains a relevant topic. In particular, it is important to understand how the habits and practices of street-level bureaucrats may result in an unjust allocation of public resources. This article provides evidence on how the administrative discretion conferred on school principals may result in an efficient but unfair condition regarding the allocation of students across schools, thus undermining social equity. By exploiting a natural experiment, we are able to provide reliable evidence on how controlling administrative discretion decreases the segregation of students based on their socioeconomic status.

Practitioner Points

- An inadequate conceptualization of social equity by street-level bureaucrats may compromise the fulfillment of organizational goals regarding social outcomes.

- The implementation of cost-reducing policies should be constantly evaluated based on reliable measures of how these policies will affect “nervous areas” of government such as social equity.

- Without appropriate checks and effective training for public officials, policies that allow administrative discretion without oversight may result in an efficient but unfair distribution of public goods.

- Procedures such as randomization that reduce the effects of personal bias may result in a fair method of allocating resources, especially when policy makers lack reliable information to select beneficiaries and street-level bureaucrats lack proper training.

Social equity is a concept that results from the views of a generation of scholars who, in the late 1960s, contravened the “traditional ideas of a politics–administration dichotomy and public administration practiced by neutral competents” (Norman-Major 2011, 233), suggesting that practitioners and scholars should be not only concerned about whether public agencies reach certain levels of efficiency, effectiveness, and economy but also aware of “for whom government operates” (Norman-Major 2011, 237). By defining social equity as “the fair, just, and equitable management of all institutions serving the public directly or by contract, the fair and equitable distribution of public services and implementation of public policy, and the commitment to promote fairness, justice and equity in the formation of public policy” (National Academy of Public Administration, cited in Gooden and Portillo 2011, 61–62), advocates have proposed a model of government that is dependent on the success of transforming public officials into actors who share the goal of reducing inequities in any policy process. Achieving social equity, then, is contingent on finding methods to influence public officials’ perceptions and decisions regarding the selection of policy options, the design of budgets, the evaluation of results, and the selection of potential recipients of public resources.

Although highly desirable, inserting social equity as a guiding principle for public officials is not a simple process. As Frederickson (2010) notes, accepting equity as a relevant goal among others traditionally followed (e.g., efficiency or economy) means that bureaucrats will constantly face moral dilemmas during the design and implementation of policies that they may not be prepared to address. In addition, practitioners will find it difficult to operationalize the notion of social equity because of the lack of conceptual clarity regarding the term, the limited importance this concept has during the preservice training of future public officials, and the lack of empirical research on social equity (Gooden and Portillo 2011).

How public officials address these dilemmas will echo experiences, training, and personal considerations (e.g., the perception of organizational goals, stereotypes, or even their own interpretations of the policy goals). All of these factors are typically grouped in what Lipsky calls symbolic constructs, which aim to reduce uncertainty, justify decisions, and even increase efficiency in decision-making processes (Lipsky 1969, 12). Depending on how public officials conceptualize equity, the social constructs that they build may inadvertently result in unfair conditions for some population groups.

Depending on how public officials conceptualize equity, the social constructs that they build may inadvertently result in unfair conditions for some population groups.

This article explores how the administrative discretion exercised by street-level bureaucrats, without proper reflection on the effects of the developed “routines and simplifications” noted by Lipsky (1969), may result in “administrative evil,” whereby “individuals and groups can engage in evil acts without recognizing the consequences of their behavior, or when convinced their actions are justified or serve the greater good” (Adams 2011, 277). To identify how discretion may result in routines that reproduce administrative evil that diminishes social equity, we exploit an exogenous variation resulting from a change in a local regulation guiding the allocation of students between morning- and afternoon-shift schools in the public primary schools located in a Mexican state. This situation presents a unique setting, given that before this legal reform, the allocation of students to school shifts completely depended on the discretionary decision of school principals, frequently resulting in the concentration of the poorest, oldest, and lowest-performing students in the afternoon-shift schools (Cárdenas 2011). 1 According to Cruz (2012), school principals’ decisions regarding the allocation of students across school shifts can be explained by the fact that principals either lack a proper conceptualization of equity or are unaware of the potential consequences of their decisions with regard to equity.

To present our findings, this article is organized as follows: In the first section, we present a brief discussion about the relationship between administrative evil, street-level bureaucrats, and social equity. In the next section, we describe the change in policy, data, and analysis strategy. In the following section, we present the results of the analysis and describe the main findings. Finally, we discuss the results and conclude with some ideas about practical implications and recommendations for future research.

Social Equity, Street-Level Bureaucrats, and Administrative Evil

Education is commonly accepted as a mechanism for reducing social inequities. As described by Dewey in the early twentieth century, public schools are conceived as institutions that are designed to give every individual “an opportunity to escape from the limitations of the social group in which he was born” (Dewey and Dewey 1915, 24). Furthermore, as Frederickson notes, “public education is still the primary engine driving the allocation of social and economic goods, and the level of one's education is still the best predictor of one's future success or achievement” (2010, 113).

Public education systems become an ideal space for discerning how public officials handle moral dilemmas and how public agencies respond to specific challenges regarding the administration of public justice through the distribution of scarce resources aimed at reducing unjust differences across populations. However, even in educational management, where promoting social equity seems to be a natural and unmistakably shared goal among public officials, different issues emerge that may jeopardize the effectiveness of public agencies in adequately distributing educational opportunities.

For instance, as Gooden notes (2014, 9), conceptualization of social equity depends on how organizations define organizational justice. Given that “all organizations have cultures that largely establish and maintain their hierarchy of values, such as efficiency, effectiveness, quality, citizen participation, and innovation,” conceptualization of issues such as social equity may be grounded in “an extended application of organizational justice,” thus capturing “nervous areas of government” that define how a public agency “considers, examines, promotes, distributes, and evaluates the provision of public justice in areas such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, class, and ability status.”

In addition to organizational values (hierarchies of values), according to Gooden, three additional factors will determine how organizations react to public justice: external environment (triggers to focus on equity), senior public administrators (the “tangible power” within organizations), and public servants (the implementers of decisions). Although the interaction of all of these components will thus determine how public agencies face equity issues, for the purpose of this study, we will focus on the role of public officials or street-level bureaucrats, who, “as Lipsky explains, … implicitly mediate aspects of the constitutional relationship of citizens to the state” (Gooden 2014, 8).

How street-level bureaucrats may contribute to administrative evil in “nervous areas of government” is an important empirical question. Research on social equity should include the identification of the extent to which public officials may involuntarily contribute to diminishing it, either by blindly applying rules and policies or by misinterpreting how administrative discretion should be exercised. In this regard, Adams (2011, 277) indicates that one of the key aspects to be analyzed is how the predominance of technical rationality in modern organizations may result in moral inversions that may end in practices of administrative evil, where “groups engage in evil acts without recognizing the consequences of their behavior,” even believing that “their actions are justified or are serving the greater good.”

It is important to emphasize that the nature of street-level bureaucratic work leads to the construction of habits and, occasionally, undesirable practices regarding the use of administrative discretion, affecting the allocation of resources. For instance, practices such as “creaming” or “cherry-picking,” which occur when street-level bureaucrats use their discretion to decide among possible recipients of public benefits, have been observed in the operation of public schools in Mexico. Indeed, previous studies suggest that street-level workers may favor clients with similar ethnic backgrounds or overreact to rules regarding racial discrimination (Lipsky 1980; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2012). The effect of street-level bureaucrats’ discretionary behavior on social equity may be explained by at least four interconnected factors: (1) the need for bureaucracies to be flexible in responding to unique situations and individual circumstances, (2) the aim of frontline workers to effectively improve the lives of clients, (3) public programs’ requirement to differentiate among recipients, and (4) the workloads and limited resources of frontline bureaucrats (Lipsky 1980).

As Adams and Balfour (2006, 682) suggest, administrative evil is observed in a continuum from “relative ignorance” to “deliberate” actions. On a daily basis, street-level bureaucrats must address decisions that require the materialization of social equity, particularly when deciding on the beneficiaries of public programs. Therefore, a first issue related to the feasibility of introducing social equity as a guiding model for decision making among teachers and school principals is understanding whether they are effectively informed and willing to make decisions that modify equality and equity conditions. Thus, it is centrally important to systematically analyze the determination of equity outcomes and the capacity of top managers to improve such outcomes and understand the consequences of their “informed” decisions.

On a daily basis, street-level bureaucrats must address decisions that require the materialization of social equity, particularly when deciding on the beneficiaries of public programs.

Two well-grounded assumptions are relevant for the purpose of this study: (1) discretion is inevitable at the front lines of public service, and (2) policy outcomes are almost always decided on the ground as a result of the interaction of several factors that influence the decisions of public officials. Before stating our main working proposition, it is important to indicate that adherence to social equity from the perspective of street-level bureaucrats requires reaching an equilibrium fostered by a public intervention that provides reliable information and sensitizes them to the unintended effects of their decisions on the allocation of public resources and the masked costs of privileging technical rationality as the main basis of efficacy and legitimacy.

In the analysis that we present next, we explore the extent to which the discretion conferred on street-level bureaucrats, exercised without the guidance of a proper conceptualization of social equity, results in biased decisions that affect underserved populations. However, when studying the effect of administrative discretion on inequities, it is important to bear in mind that such discretion is fundamental to ensuring an efficient provision of public services. For this reason, our aim is to empirically test whether street-level bureaucrats may involuntarily become involved in practices of administrative evil while exercising public discretion and the extent to which a shift in the rules may reduce the effects of these practices.

The Double-Shift Schooling Model

Public officials frequently face trade-offs among efficiency, quality, and equity in the operation of education systems. These trade-offs are common in the implementation of policies aimed at increasing enrollment rates, given that, frequently, most of the available (and financially feasible) policy options may inadvertently result in an inadequate distribution of educational opportunities, with the poorest population being affected the most.

The double-shift schooling (DSS) model is considered an efficient intervention for increasing the number of enrolled children who otherwise would be out of the education system. Under this model, schools “cater to two entirely separate groups of pupils during a school day, [and] each group uses the same buildings, equipment and other facilities” (Bray 2008, 17), thus reducing the operating costs of providing education services. The DSS model has been implemented in several countries and regions for decades. In Mexico, it has been implemented since the late 1950s in the basic education system, when increasing the enrollment rates in rural and unattended areas across the country became a national priority. Presently, the 32 state education systems operate schools based on this model in urban and rural areas, although the implementation of the DSS model in Mexico has been associated with the segregation of students based on socioeconomic status, as reported by Cárdenas (2011), who found that, on average, afternoon-shift primary schools in Mexico have a higher concentration of poor and indigenous students.

Regardless of a student's background, there is evidence that students who attend the afternoon shift tend to receive a lower quality of education because of several factors. For instance, Michaelowa (2003) has reported that in sub-Saharan Africa, there is “overwhelming evidence that double-shift classes imply considerable disadvantages for the students concerned.” Additionally, regarding one of the most important factors that explains student performance, Ingebo (1953) has documented how teachers who work in double-shift schools have complained about the “lack of time to work with pupils” and the fact that the “intensity of work creates an atmosphere that is unfavorable to learning.” In Mexico specifically, a large proportion of teachers in the second shift have already worked the first shift at another school. This situation gives them less time to prepare lessons and review student work, and they likely tire more because of the longer workday.

We have to be very careful about the characteristics of the students we will enroll in our schools [morning shift]. If we have 15 at-risk students and we enroll 20 more, we would definitely modify the working environment of our school. We would not be able to implement a real school project, and we would have to devote all our attention to these students. If we accept good students, they will graduate on their own. (2009, 33)

A plausible consequence of this behavior has been documented to produce differences in the inputs and social composition between the morning- and afternoon-shift schools (Saucedo 2005; Zehr 2002).

The segregation of students between school shifts (with the result that more affluent students are enrolled in morning-shift schools) may be explained by the lack of regulation guiding the student selection processes, as noted in the aforementioned study's description of the existence of a “cherry-picking” process implemented by school principals, whereby they decide who will be enrolled in morning-shift schools based on perceptions of socioeconomic status, academic performance, or willingness to pay school fees. 2 In the absence of specific rules and procedures, school principals frequently implement this selection process without further consultation with other members of the school community or any consideration given to issues of equity or diversity (Cruz 2012).

Given the characteristics of the DSS model, it results in an excellent laboratory for exploring whether the administrative discretion exercised by school principals results in practices of administrative evil and how a modification of the regulation provides evidence on the magnitude of the effects on social equity that these practices may have. The next sections describe our analytical strategy, interpretation, and findings.

Methods

Analysis Strategy

One problem of studying the effect of the decisions and behavior of street-level bureaucrats is the potential problem of sample selection bias. Sample selection bias (Schneider et al. 2007) is the methodological challenge of identifying whether a reduction in the discretion of school principals results in a more equal distribution of poor students across school shifts while using observational data (see the Methodological Appendix to this article). One opportunity to overcome the methodological restrictions of sample selection bias is the exploitation of “natural experiments,” defined as “situations in which some external agency, perhaps a natural disaster, or an idiosyncrasy of geography or birth date, or a sudden unexpected change in a long-standing educational policy, ‘assign’ participants randomly to potential ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ conditions” (Murnane and Willett 2010, 135), thus reducing “sample selection bias.” 3

This condition occurred in Mexico when, in 2009, a state public education agency decided to enforce a new rule demanding the allocation of students in morning- or afternoon-shift schools by a public lottery. The lottery would occur when the demand for places in any morning-shift school exceeded the capacity of the school, representing an important policy shift with regard to the allocation of students across school shifts in public schools. Before the change in the enrollment process policy, students were allocated across school shifts based on decisions made freely by school principals, which still occurs in the rest of the country. This situation is the result of official regulations and informal procedures widely implemented in public schools across Mexico, where school principals enjoy full discretion with regard to the distribution of resources within the school community, the enrollment of students and teachers, and the allocation of students across school shifts. Moreover, in these schools, parents and school councils typically have limited influence in key decisions regarding the operation of schools.

Thus, the enactment of this new regulation (“the external agency”) represents a significant reduction in the discretion enjoyed by school principals with regard to the allocation of students across school shifts and the composition of cohorts in their schools based on socioeconomic criteria. The new enrollment system was initially implemented by the state education agency through the distribution of letters informing every parent about the updated procedure for enrolling children in public primary schools. In this letter, in addition to noting that parents would be able to select a public school to enroll their children in, local authorities explained that a public lottery would be organized in each of the schools where the demand exceeded the number of available seats for new students in the morning shift (Under-Secretary for Basic Education, interview, May 2010). In practice, the policy variation resulted in an intervention that aimed to reduce the discretion enjoyed by principals in enrolling students, seeking to reduce the inequalities resulting from the public perception that morning-shift schools were more effective.

However, this unique case required a reliable counterfactual to allow the identification of changes in the behavior of school principals. For this purpose, we conducted a consultation with the remaining state governments about the criteria used to allocate students between morning- and afternoon-shift schools. The consultation was based on formal requests for information delivered to each of the state governments in the country through requests supported by local “access to information” acts. The information revealed that with the exception of the state where the natural experiment occurred, the decision to allocate students to morning- or afternoon-shift schools mostly continued to be the responsibility of school principals, with little variation across states, mainly because of the use of additional information during the selection process, such as thresholds based on test scores and the consideration of previous school grades.

To estimate whether the restriction of discretionary power among school principals generated by the lottery had any effect on the gaps identified between morning- and afternoon-shift schools, we used a difference-in-difference estimator. 4 By using this estimator, we were able to measure whether, compared with the morning-shift schools operating in the same building, afternoon-shift schools had a lower concentration of disadvantaged poor students after the implementation of the new allocation process. We measured the concentration of disadvantaged students by comparing two key outcomes between shifts: the percentage of enrolled students who had attended one year of preschool and the percentage of students who were recipients of PROSPERA, a national cash transfer program for low-income families (the relevance of these variables is explained in the next section).

where Y bt is the outcome variable corresponding to building b in year t; Post is a variable that is set to 1 if year t is 2009 and later (the period when the random allocation of students was implemented); Treatment is a variable that is set to 1 if the building b is located in the state where the random allocation process was implemented; Post * Treatment is an interaction that aims to capture the impact of the new allocation process; Υ is a set of control covariates; and ε b,t is the error term across buildings and time. β0 through β3 are the regression parameters to be estimated.

The interpretation of the model is simple: if the interaction of Post (school years 2009–10 to 2013–14) and Treatment (being a double-shift school located in the state where the lottery was implemented) is statistically significant, then the double-shift schools located in the state where the lottery occurred had a trend that was significantly different from the double-shift schools located in any of the states from the comparison group after the random allocation system was implemented. In other words, a significant β3 parameter would imply that after the implementation of the public lottery, double-shift schools in the state where the lottery was implemented had a different trend in the magnitude of the differences between morning- and afternoon-shift schools in the outcome of interest compared with the double-shift schools where the enrollment policy was not modified. Moreover, the sign of the parameter will identify whether afternoon-shift schools are reducing or increasing the percentage of students measured in the outcome of interest. Given the current distribution, with a higher concentration of poor students in the afternoon-shift schools, and given how we defined our dependent variables, a positive sign in the parameter of interest would indicate that the gap between morning- and afternoon-shift schools was reduced. By contrast, a negative sign would indicate that afternoon-shift schools increased the number of enrolled poor students in the state that introduced the treatment. 5

Data Collection and Measurement

To conduct our analysis, we used information from two databases, including information collected by the Mexican government: the National School Census from the Ministry of Education and the national database of PROSPERA recipients, implemented by the Ministry of Social Development.

The National School Census (known as Formato 911) is a national database with information that has been collected since 1975 from every private and public school operating in Mexico. The information is collected at the beginning and at the end of every school year (running from August to June) through the administration of self-reporting questionnaires to every school principal in the country. This census is the only database with information from each of the nearly 200,000 private and public basic education schools located in the country, and it is the main source for the official statistics used to monitor the performance of the national education system (e.g., enrollment, failure, repetition, and overage rates).

- Students, disaggregated by age, grade, and sex (e.g., enrollment, number of foreign and indigenous students, special education students, and the number of years that first-grade students attended preschool)

- Teachers (e.g., academic achievement and whether they teach single- or multigrade groups in the school)

- Organization of the school (e.g., the number of groups per grade, the number of available classrooms, the number of employees, the amount of annual school fees, and whether the school has multigrade instruction).

The PROSPERA recipient database identifies the number of recipients studying at each of the primary schools located across the country, disaggregating information by sex. The PROSPERA program (formerly known as Oportunidades or PROGRESA) has been implemented in Mexico since 1997 with the aim of reducing “the current level of poverty in Mexico and to increase the future productivity of children from poor families that should enhance the welfare of these families in the long run” (Schultz 2000, 1). It is based on the delivery of monthly stipends to the poorest families of the country, provided that they comply with different mandates, such as enrolling all children in schools, attending training sessions aimed to improve health conditions, and providing nutritional support.

Regarding the school sample, its size and characteristics were defined by narrowing down the population of public primary schools in the country to a sample composed exclusively of schools operating under the DSS model, identified after pairing morning- and afternoon-shift schools that share a building according to their registered address.

From the sample of nearly 17,000 morning- and afternoon-shift public schools operating in the country, we built a panel of 9,368 schools (sharing 4,684 buildings) based on the criterion that the schools to be included in our final sample should have been operating as double-shift schools during the entire period from school year 2004–05 to 2013–14, to control for the fact that an afternoon-shift school is typically opened only after a morning-shift school has been operating in that building. The main reason for controlling for this condition is that the inclusion of recently opened schools (either morning- or afternoon-shift schools) may result in unobserved differences regarding the organization of the school, at least when compared with the other school shift previously operating in the same building (e.g., the lack of experienced school principals or integrated communities), a situation that would cause misleading results.

Table 1 includes the descriptive statistics for the final sample of 9,368 morning- and afternoon-shift schools. It is important to note that although this table depicts a lower teacher–student ratio for afternoon-shift schools (capturing a higher demand for morning shifts). Previous studies (Cárdenas 2011) have found significant differences in the characteristics of teachers across school shifts associated with less effective teaching practices observed in the afternoon shift. Therefore, as expected, the table shows a higher proportion of at-risk students in afternoon-shift schools.

| Morning Shift | Afternoon Shift | |

|---|---|---|

| Total student enrollment | 411.33 | 237.89 |

| Number of teachers | 12.47 | 8.87 |

| Number of groups | 12.61 | 9.27 |

| School fee (annual, MXN) | $239.03 | $194.99 |

| Indigenous students | 0.58% | 0.79% |

| Special education students | 1.26% | 1.93% |

| Overage rate (first grade) | 5.00% | 12.70% |

| Repetition rate (first grade) | 3.35% | 6.65% |

| Failure rate (first grade) | 3.35% | 6.82% |

| Preschool attendance (one year) | 22.05% | 33.18% |

| PROSPERA/Oportunidades recipients | 10.14% | 13.98% |

- Percentage of PROSPERA recipients enrolled in each school: This value is estimated as the number of PROSPERA recipients enrolled in school j divided by the number of students enrolled in first grade in school j at the beginning of school year t, multiplied by 100.

The targeting process of PROSPERA has been considered effective for identifying the poorest families in the country (Coady, Grosh, and Hoddinott 2004). The importance of this variable is that it provides a reliable measure of the poverty concentration within schools, given that PROSPERA recipients are selected based on a two-stage process: in the first phase, the poorest communities across the country are identified. Then within those communities, after administering a survey and receiving feedback from members of the community, the program selected the neediest families. This process is performed outside the school, thus providing an unbiased measurement of poverty conditions.

- Percentage of students who attended preschool for only one year before being enrolled in primary school j: This value is computed as the number of students in first grade who attended preschool only one year and enrolled in school j at the beginning of the school year t divided by the number of students enrolled in first grade in school j at the beginning of school year t, multiplied by 100.

The rationale behind using the condition of attending preschool for only one year as a measurement of socioeconomic status is based on the fact that parents “make choices about how much time and other resources to invest in their children [i.e., their education] based on their objectives, resources, and constraints” (Rumberger 2001, 16). Given that in Mexico enrolling children in preschool is free and mandatory, late enrollment in preschool likely reflects family environments with reduced cultural and economic capital. As demonstrated in previous studies from the United States, early attendance in preschool is associated with family income: in the population group with the lowest income level, only 42 percent of families enrolled their three-year-old children, whereas in the group with the highest income, nearly 71 percent of children of the same age were enrolled (Barnett and Yarosz 2007).

We estimated the difference between morning- and afternoon-shift schools sharing a building for each of our measures, PROSPERA and PRESCHOOL, to identify whether school principals allocated poor students equally across school shifts. We used the estimated differences for each shared building as our dependent variables to identify three situations: (1) which of the school shifts had a higher concentration of poor students, (2) whether this concentration varied over time, and (3) whether the differences between school shifts were reduced in the state where the reduction in school principal's administrative discretion occurred.

The distribution of the dependent variable shows that in most cases, the outcome had a positive value. This sign implies that, on average, an afternoon-shift school had a higher concentration of PROSPERA recipients than a morning-shift school operating in the same building. In an ideal situation, where principals intentionally allocate students equally across school shifts, the mean value of this variable would be close to zero, implying that morning- and afternoon-shift schools have the same share of PROSPERA students or one-year PRESCHOOL students. According to this model, a negative sign in the parameter of interest (the interaction term Post * Treatment) would mean that compared with the percentage of poor students enrolled in morning-shift schools, the percentage of poor students enrolled in afternoon-shift schools was reduced after the implementation of the lottery.

Results

Tables 2 and 3 include the estimates of coefficients and standard errors from the fitting of the regression model for our two key outcomes. In the first model, the results show a negative, significant parameter for the Post * Treatment interaction, suggesting that the afternoon-shift schools located in the state implementing the lottery enrolled, on average, fewer students who were PROSPERA recipients once the discretion of principals was reduced (approximately 1.81 percent). This variation reflects a more equal distribution of the poorest students across school shifts. In other words, the results show that the poorest students were enrolled in afternoon-shift schools in a higher proportion in the absence of treatment.

| H0 : β = 0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | z | p |

| Intercept | 3.97 *** | .09 | 42.29 | .00 |

| Post | −0.39 *** | .05 | −7.14 | .00 |

| Treatment | 2.53 *** | 1.01 | 2.52 | .01 |

| Post * Treatment | −1.81 *** | .59 | −3.04 | .01 |

| R 2 | .01 | |||

- *** p < .001.

| H0 : β = 0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | z | p |

| Intercept | 10.25 *** | .31 | 32.49 | .00 |

| Post | 1.51 *** | .32 | 4.68 | .00 |

| Treatment | 3.76 | 3.28 | 1.14 | .25 |

| Post * Treatment | −9.49 *** | 3.30 | −2.88 | .01 |

| R 2 | .01 | |||

- *** p < .001.

The described trend observed in the first outcome is confirmed when interpreting the results of the regression for students who attended preschool for only one year. The parameter estimate of the Post * Treatment interaction identifies a reduction in the difference between morning- and afternoon-shift schools of approximately 9.49 percent less than the difference between school shifts in schools located in other states enrolling students solely based on principals’ decisions. This difference is likely a result of the random assignment of students across school shifts, thus suggesting that a reduction in the discretion of school principals resulted in a more equal distribution of poor students between morning- and afternoon-shift schools.

The results presented here provide evidence to support the idea that the afternoon-shift schools located in the state where the lottery occurred had a reduced share of poor students after the implementation of the lottery. Given the common practice reported in previous studies, where afternoon-shift schools had a higher concentration of poor students, the findings confirm that reducing school principals’ discretion over the allocation process across morning- and afternoon-shift schools resulted in a more homogeneous distribution of poor students across school shifts.

Discussion

The discretion conferred on school principals and exercised without guidance by a proper conceptualization of social equity may be one of factors that explain the biased decisions affecting underserved populations. Our findings demonstrate that the implementation of a public lottery to lessen the administrative discretion of school principals tempered the concentration of the poorest students in the afternoon-shift schools. These results suggest that administrative discretion without proper controls, training, and knowledge may result in administrative evil, whereby public officials will value certain criteria in their decisions, such as effectiveness, efficiency, or economy, over equity (Adams and Balfour 2004; Adams, Balfour, and Reed 2006).

The implementation of a public lottery to lessen the administrative discretion of school principals tempered the concentration of the poorest students in the afternoon-shift schools.

Despite the significant results produced by this public lottery, this intervention alone is unlikely to be sufficient to reduce administrative evil. The limitation of the instrument is the result of a potential adaptive behavior by school principals, who are likely to adjust their conduct to react to the lottery. For instance, they may be willing to report a reduced number of applicants to avoid the implementation of the lottery or even mislead parents about the results of the lottery process to circumvent the system. To some extent, these interventions confront the well-documented difficulties of designing organizations to support ethical behaviors (Cooper 2004) that, by themselves, are unable to create sufficient institutional incentives to promote social equity. Implementing actual change in the behavior of school principals is a complex and lengthy process that may require more than temporarily modifying the incentives of school principals’ decisions, as in the case of the lottery.

Among the actions that the system could take to promote long-term and stable change, raising awareness among school principals about the consequences of their behavior or decisions in terms of social equity or teaching them about the hidden costs of reducing social equity in a society is a fundamental but complicated task. These changes require the top management to modify the current behavior of public officials by modifying incentives based on extrinsic and intrinsic factors.

The generation of extrinsic motivations opens an opportunity to design new interventions that aim to increase the cost of reproducing inequities by modifying the institutional culture and shared values in relation to social inequities (Gooden 2014). This intervention has the potential to modify the hierarchy of values of public officials. In addition, public agencies need to reward any activity oriented toward detecting and diminishing any source of social inequity, thus creating an extrinsic motivation to change the preferences of street-level bureaucrats and reducing unfair conditions that were previously reproduced.

To influence the intrinsic motivation of principals, the school system needs to increase principals’ knowledge of the negative effects caused by unfair inequalities, particularly how, at a social level, they overshadow any positive effect related to efficiency. The case of Mexico shows that it seems to be imperative that street-level bureaucrats are trained to possess the skills that will help them identify different sources of inequities. In addition, the top-level management in the school system needs to create awareness among school principals about the consequences of their decisions in terms of issues of social equity. In summary, the use of interventions that promote both extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation is more likely to result in an informed decision-making process, thus creating personal commitments to detect and avoid administrative evil.

In the same sense, there is limited empirical research on how to better prepare street-level bureaucrats to handle moral dilemmas (see, e.g., Kelly 1994). However, the lack of evidence on effective interventions to support public officials in improving performance with regard to the promotion of social equity creates an opportunity to search for specific models from other disciplines that aim to increase social awareness in nervous areas of government (Gooden 2014). In particular, it may be helpful to look at how agency leaders promote ethical or moral behavior to identify possible venues for reducing practices of administrative evil, such as practicing “transformational leadership” styles (Griffith 2004, 334). Given that a large part of the seminal works on this topic have not been translated into empirical interventions, there is an important opportunity to increase our understanding of the relationship between specific interventions grounded in the research literature and the behavior of street-level bureaucrats by using innovative approaches such as experimental and quasi-experimental methods.

Finally, we noted earlier that school principals may inadvertently enroll students under some criteria that reproduce social inequities. For this reason, advancing social equity in elementary education may require lowering the importance of commonly accepted performance indicators, such as student performance (Meier and O'Toole 2003) and test scores, dropout rates, transfer rates, and attrition rates (Rumberger and Palardy 2005). Given that these performance indicators are defined as part of the political process, involving not only education authorities but also members of the research community and other interest groups, changing them requires a national discussion about the importance of promoting social equity by avoiding the segregation of low-income children within schools. At the operational level, the introduction of cultural audits, as suggested by Gooden (2014), has the potential to result in a different approach to the evaluation of the school's performance and the types of incentives that influence the decisions of principals. A cultural audit requires identifying current values and providing a description of the desired culture and values to advance social equity. The result of this audit may generate specific modifications of standards, values, and beliefs that promote values such as social equity inside public agencies (Gooden 2014).

This improvement requires adopting and designing “value-added” performance indicators (Meyer 1997, 284) that have the potential to isolate the contribution of schools to student achievement from other external factors, such as those used in “cherry-picking” outstanding students. However, these transformations would require the production of more research and evidence to demonstrate the social implications of double-shift schooling on equity to raise awareness of the issue and put it on the national policy agenda. Moreover, this research must contribute to demonstrating that a “business as usual” approach that ignores how street-level bureaucrats reproduce or foster social inequities in pursuit of efficiency will result in the reproduction of unfair conditions that, in the long term, affect the legitimacy and effectiveness of any public agency.

Conclusion

Since the publication of Herbert Simon's seminal work (Meier 2015; Simon 1946), the study of how public bureaucrats make decisions has been one of the central topics in the field of public administration. However, the field quickly realized that decision making was concerned not only with being efficient but also with being able to promote the ethical behavior of public administrators to pursue other values considered higher, such as social equity (Frederickson 1980, 1990, 2010; Waldo 1980).

This article is an initial effort to estimate some of the negative effects associated with the administrative evil generated by the pursuit of efficiency and efficacy in public agencies. By exploiting a natural experiment, this study provides reliable evidence on how controlling administrative discretion decreases the segregation of students within schools based on their socioeconomic status, thus reducing the effects of practices of administrative evil. Two main contributions from this study should be highlighted. First, it provides examples of the viability and convenience of exploring the use of quasi-experimental methods to address “traditional” questions in the field of public administration. This methodological approach makes it possible to test empirical questions that have traditionally posed challenges to research, such as the case of data with the problem of sample bias selection. Second, the study provides empirical evidence regarding the negative effects of practices of administrative evil that has the potential to sensitize different audiences to the need to introduce innovative instruments to tackle this problem.

Although this article provides some evidence on how the behaviors of bureaucrats in public agencies may reproduce inequities, we still know little about how to empirically change them, which presents a challenge and an opportunity to conduct new research on a topic that has been partially addressed since the 1960s (Gooden 2015). Finally, it is important to call attention to the importance of empirically studying theories that have attempted to incorporate values to promote ethical behaviors. Such studies should be conducted not only in developed countries but also in developing countries to advance our understanding of how public administration values are interpreted in different regions and contexts (Meier 2015). For instance, this situation calls for the study of how different mechanisms such as ethics courses could help public officials internalize other important goals. Moreover, there is also a need for further study of the role of unions and professional associations in any effort to educate public officials in pursuing social equity issues. These explorations are fundamental for developing countries, where professionalization is frequently only associated with the creation of civil or professional service systems, which concentrate mainly on the introduction of formal institutions to improve their public administration systems, paying little attention to the scale of values that they advance.

Methodological Appendix

Sample Selection Bias

This type of bias is observed when differences in outcomes from two different populations (in this case, schools where students are allocated across school shifts based on the results of a lottery, compared with schools where principals freely select students to be enrolled in each school shift) are not adequately estimated because one of the groups may be different from the other in several dimensions. A difference in characteristics between groups (a likely condition in observational studies) increases the probability of erroneously attributing the reduction of school principals’ discretion to some differences in the selected outcomes, although these variations may indeed be explained by other factors.

Ideally, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the best option for estimating the effect of an intervention, although an RCT requires a research design that is not always a feasible option for the agency in charge of a program. In the absence of an opportunity to conduct an RCT, a different approach should be explored to ensure that “there is a transparent exogenous source of variation in the explanatory variables that determine the treatment assignment” (Meyer 1995, 151) to overcome sample selection bias.

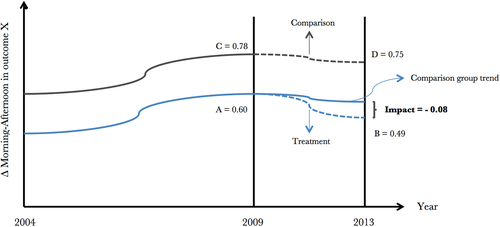

Difference-in-Difference Estimator

Figure A1 represents the conceptual model behind this method, in which the basic notion is that it is possible to isolate the effect of any intervention by subtracting the difference in any given outcome at two time points from a treated comparison group (values in points A and B) from the difference at two time points of a comparison group (values in points C and D). Therefore, the effect of a treatment (“differences of differences”) can be calculated as follows: DiD = (B − A) − (D − C) (Gertler et al. 2010).

Source: Adapted from Gertler et al. (2010).

The difference-in-difference estimator helps reduce the probability of erroneously attributing any variation in the selected outcomes to the implementation of the lottery for the student allocation process when these changes may be explained by previous differences in the characteristics between the “comparison” group (nonrandom allocation) and the “treatment” group (random allocation).

Acknowledgments

The authors are listed in alphabetical order. Both authors are equal and primary coauthors. We would like to thank the editors of this journal and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments for improving this manuscript. We also thank Adrian Guízar and Ana Martínez for their contributions to an early version of this study. Finally, we are in debt to Alfonso Miranda, Francisco Cabrera, and Susan T. Gooden for their valuable suggestions.

Notes

Biographies

Sergio Cárdenas is professor in the Public Administration Division at Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico City, Mexico. His primary interest is educational policy. He is editor of Reformas and Políticas Educativas, as well as member of the Global Education Innovation Initiative. He earned his Ed.D. from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.E-mail: [email protected]

Edgar E. Ramírez de la Cruz is professor in the Public Administration Division at Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico City, Mexico. His primary interests are urban governance and sustainability. He is also interested in public management, education policy, and policy networks. He is editor in chief of Gestión y Política Pública and associate editor of Urban Affairs Review. He earned his PhD from the Askew School at Florida State University. E-mail: [email protected]