Sleep disorders in the elderly: a growing challenge

Abstract

In contrast to newborns, who spend 16–20 h in sleep each day, adults need only about sleep daily. However, many elderly may struggle to obtain those 8 h in one block. In addition to changes in sleep duration, sleep patterns change as age progresses. Like the physical changes that occur during old age, an alteration in sleep pattern is also a part of the normal ageing process. As people age, they tend to have a harder time falling asleep and more trouble staying asleep. Older people spend more time in the lighter stages of sleep than in deep sleep. As the circadian mechanism in older people becomes less efficient, their sleep schedule is shifted forward. Even when they manage to obtain 7 or 8 h sleep, they wake up early, as they have gone to sleep quite early. The prevalence of sleep disorders is higher among older adults. Loud snoring, which is more common in the elderly, can be a symptom of obstructive sleep apnoea, which puts a person at risk for cardiovascular diseases, headaches, memory loss, and depression. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder that disrupt sleep are more prevalent in older persons. Other common medical problems of old age such as hypertension diabetes mellitus, renal failure, respiratory diseases such as asthma, immune disorders, gastroesophageal reflux disease, physical disability, dementia, pain, depression, and anxiety are all associated with sleep disturbances.

INTRODUCTION

The importance of sleep for the overall health and well-being of the elderly has been increasingly recognized.1, 2 Psychiatrists, neurologists, and geriatricians, general practitioners should have sound knowledge about the changing pattern of sleep from infancy to old age. Additionally, the sleep problems faced by the elderly, and the consequences of inadequate and inappropriate sleep in determining the quality of their life, have gained recognition recently.3-7 It is widely believed that social participation is the key to healthy ageing. However, data from the US National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project has shown that older adults with greater social participation slept better, but increasing social participation did not improve sleep.8

The percentage of the elderly population is growing due to increased life expectancy and improved socioeconomic development. Surprisingly, in the World Health Organization's 2015 World Report on Ageing and Health, there is no mention of sleep disorders.9 In India, the aged population is expected to be around 20–25% of the population by 2050. By then, the elderly population would be more than 25% of the population in developed nations. It already exceeded 30% in Japan in 2012. The increase in the aged population will bring with it a huge burden of sleep-related health problems. Although ageing is a global phenomenon, little data are available on regional trends in sleep-related problems.

SLEEP STAGES, TIME, AND ARCHITECTURE OF DIFFERENT AGE GROUPS

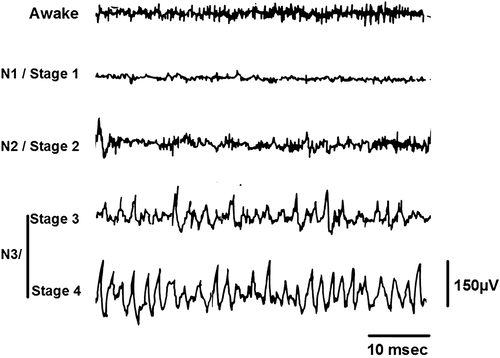

Behaviourally, sleep is characterized by reduced motor activity, decreased response to stimulation, stereotyped posture, and relatively easy reversibility. Scientifically, sleep is defined on the basis of electrophysiological signals like electroencephalogram (EEG), electromyogram, and electro-oculogram. The modern definition and classification of sleep was suggested initially by Nathaniel Kleitman in 1939, but it was described in detail in a manual written by Rechtschaffen and Kales in 1968.10, 11 Normal human sleep was classically divided into rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM (NREM) sleep, which consisted of four stages: S1, S2, S3, and S4. However, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine slightly modified the staging rules and terminologies in 2007: S3 and S4 were grouped together as N3, and S1 and S2 were renamed N1 and N2.12

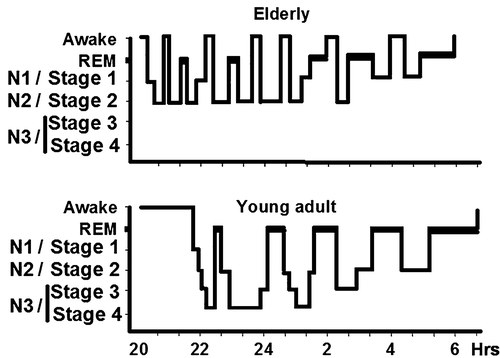

Sleep starts with a period of NREM sleep (slow wave sleep) in healthy young adults (Fig. 1). REM sleep takes place after a short period of NREM sleep.13, 14 This alteration between NREM and REM occurs about four or five times during a normal night's sleep. As NREM sleep progresses to deeper stages, the EEG shows increasing voltage and decreasing frequency (Fig. 2). Although muscle activity is progressively reduced, the sleeper makes postural adjustments about every 20 min. During NREM sleep, the heart rate and blood pressure decline, but gastrointestinal motility and parasympathetic activity increase. In contrast, REM sleep is characterized by a profound loss of muscle tone, but the eyeballs show bursts of rapid eye movements. The EEG becomes desynchronized during this phase.

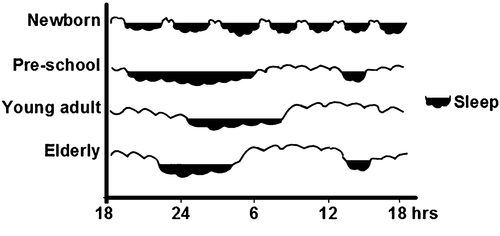

The quantity and quality of sleep change profoundly across the lifespan.15 Newborns show several sleep–wake cycles over 24 h (Fig. 3). This polycyclic rhythm passes through a biphasic pattern before a monocyclic pattern is established by the time children reach school-age. In newborns, the total duration of sleep in a day can be 14–16 h. Newborns spend a large amount of time in active sleep or REM sleep. Their sleep starts with active sleep (or REM sleep). Interactions with external synchronizers, such as light, eating, and other sensory inputs, help them to develop a circadian rhythm. Circadian sleep–wake rhythm with periodicity in physiological, biochemical, and psychological processes is modulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus as well as the pineal gland. These brain areas set the body clock periodicity to approximately 25 h, but with environmental clues (like light exposure) and activity schedule, the sleep–wake rhythm gets entrained to a 24 h day/night cycle.

In young adults, sleep of 7.0–8.5 h is considered fully restorative.16 The amount of sleep needed by each person is usually constant, although there is a wide variation among individuals. During old age, overnight sleep is often fragmented and lasts for less than 6.0–7.5 h. The elderly usually have a mid-afternoon nap for a period of about 1 h. The reason for these changes in sleep and circadian rhythms with ageing is not fully understood.

SLEEP CHANGES IN OLD AGE

Changes in the sleep patterns are a part of the normal ageing process. Older people have difficulty falling asleep and in staying asleep, due to frequent arousals. In fact, the required total sleep time remains nearly constant throughout adulthood. It is only the sleep architecture and depth that changes with ageing (Fig. 1). Older people spend more time in the lighter stages of sleep (N1 and N2) than in deep sleep (N3).15, 17-19 This results in their waking up several times during the night. This phenomenon is described as sleep fragmentation with ageing. In a recent study, the effect of age on a wide range of variables of sleep, including total sleep time, percentage of time in each sleep stage (N1, N2, N3) and REM sleep, arousals (named as macrostructure), and spectral power (microstructure), were studied. It showed that ageing had a more distinct effect on sleep microstructure—a decline in which was reflected particularly in fast spindle density, K-complex density, and delta power during N3 sleep—than on conventional sleep staging variables.20 Some reports indicated an overall decrease in total sleep time in the elderly.1, 18 The reduction in the percentage of REM sleep is significantly correlated with age in women, whereas the reduction in the percentage of slow wave sleep is correlated with age in men.19

REASONS FOR ALTERED SLEEP ARCHITECTURE IN OLD AGE

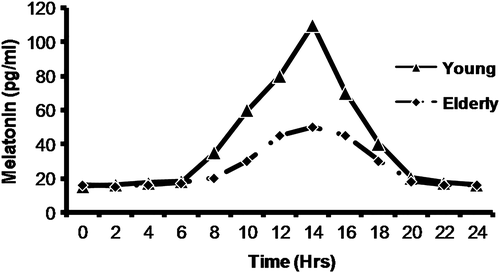

The circadian oscillations that alter body functions including sleep become less pronounced during old age. This is reflected in the decreased melatonin peak in the elderly (Fig. 4). Older people commonly exhibit advanced sleep phase syndrome, as they tend to go to sleep earlier and wake up earlier than young adults. This could be due to reduced light exposure. As such, bright light therapy is suggested as a treatment option for them.

The timing of sleep–wake cycles is regulated by two interacting regulatory systems: the sleep–wake homeostatic drive and the internal circadian clock.21 The interaction of these two systems keeps young adults alert during the day and enables them to sleep without interruption at night. As people age, the internal clock becomes less efficient,22 and this results in interrupted sleep, falling asleep earlier, and waking up earlier in the morning.23-26 Ageing reduces the amplitude of circadian oscillation in all the physiological parameters, including the melatonin level.25, 27-31 Decline in the efficiency of the central master clock—that is, the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus—is the key element responsible for this age-related decline. This affects day/night synchronization in the several peripheral cellular clocks in the metabolic pathways and endocrine mechanism. Circadian rhythms govern not only the physiological variables such as energy metabolism, sleep–wake cycles, body temperature, and locomotor activity, but they also influence the behavioural systems.32-35 It is plausible that ageing associated circadian desynchrony is responsible for metabolic imbalance, central neurodegenerative disorders, and sleep disruptions.36, 37 A recent conference report by Fung et al. discussed in detail the association between sleep and circadian rhythms during ageing.38

Decrease in EEG delta power is also associated with difficulties in initiating sleep in old age.39-41 Along with the reduction of delta power, the power in the beta waves (an indicator of cortical arousal) is increased in older individuals.39 Age-associated brain atrophy and cortical thinning are likely to contribute to these changes.40, 42

AGEING PROCESS AT CELLULAR LEVEL AFFECTS SLEEP

Ageing in general is a complex process with changes at the molecular, cellular, and genetic levels. A detailed review on the alterations in intercellular communication, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, deregulated nutrient sensing, loss of proteostasis, epigenetic alterations, and genomic instability provides insights into several interlinked components that are considered hallmarks of the ageing process.35 A progressive loss of physiological integrity as well as impaired and deteriorated body functioning increase the risk for metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and even cancer.19, 43-50 Telomeres are the chromosomal regions that are particularly susceptible to age-related deterioration.51 Insomnia in older adults (aged 70–88 years) is associated with shorter telomere length in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.52 Moreover, sleep disturbances may also enhance cellular ageing in the later years of life.52

INSOMNIA IN THE ELDERLY

Insomnia is one of the most common sleep disorders in the elderly. According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (3rd edition) by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, ‘Insomnia is defined as a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment'.53 But according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, ‘insomnia is defined as reported dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality and associated with difficulty with sleep initiation, maintenance, or early-morning awakening and that causes clinically significant distress or impairment, occurs at least 3 nights per week for 3 months, occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep, and is not better explained by another disorder or substance abuse'.54 It is important to note the emphasis on the perceived dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality in the second definition. Although polysomnographic assessment of sleep is of much significance while treating insomnia, it cannot achieve the desired objective if the patient's own feeling about his or her sleep is given due weightage. The difference in these definitions of insomnia is partially responsible for the variations in different reports on insomnia.

Although the prevalence of insomnia in the elderly population is high, there is a wide variation in reports from different parts of the world (Table 1).55-79 This variation cannot be attributed to differences in data from developed and developing nations. Also, the variation cannot be attributed purely to differences between ethnic groups, rural and non-rural population, and nursing home and non-nursing home data. A relatively low percentage (15%) of elders has insomnia in the Domkhar valley in India's Ladakh region, which is at a high altitude of 2900–4200 m.74 According to some reports, there is a higher prevalence of insomnia in the aged in nursing homes and rural areas.69, 75, 76 However, other studies have found no differences in the insomnia patterns of elders in nursing homes and in other homes.80

| Study group | Prevalence rate | Geographical region of aged population |

|---|---|---|

| Foley et al.55 | 23–34% | USA |

| Ohayon56 | 30% | France |

| Maggi et al.57 | 45% | Italy |

| Chiu et al.58 | 38.2% | Hong Kong (Chinese population) |

| Babar et al.59 | 32.6% | Hawaii (Japanese Americans) |

| Kim et al.60 | 26.4% | Japan |

| Pallesen et al.61 | 38.6% | Norway |

| Schubert et al.62 | 26.4% | USA |

| Sukying et al.63 | 46.3% | Thailand |

| Su et al.64 | 6% | Taiwan |

| Yu et al.65 | 10.4% | China |

| Bonanni et al.66 | 44.2% | Italy |

| López-Torres et al.67 | 36.1% | Spain |

| Kim et al.68 | 29.2% | South Korea |

| Li et al.69 | 49.7% | China (rural) |

| Tsou70 | 41% | Taiwan |

| Ayoub et al. 71 | 33.4% | Egypt |

| Ford et al.72 | 21.3% | USA |

| Sagayadevan et al.73 | 13.7% | Singapore (Chinese, Malay, Indian descent) |

| Sakamoto et al.74 | 15.2% | Ladakh, India |

| El-Gilany et al.75 | 62.1% | Egypt (rural) |

| Eser et al.76 | 60.9% | Turkey (nursing home) |

| Makhlouf et al.77 | 33.4% | Egypt (geriatric home) |

| Gambhir et al.78 | 32% | India (hospital) |

| Ogunbode et al.80 | 27.5% | Nigeria (geriatric centre) |

The 2004 National Health Interview Survey in the USA showed that the percentage of elderly men and women sleeping less than 6 h is as high as 20–25%.81 It has been reported that insomnia is more pronounced among elderly Hispanics than in non-Hispanic whites.82 In a small hospital-based study in northern India, researchers reported insomnia in 32% of the elderly population with multiple comorbidities.78 However, large-scale studies are required to further understand the role of ethnic differences in age-related insomnia. Although insomnia increases with age, comorbid health conditions largely influence the clinical severity.

Gender differences in insomnia in the aged population cannot be ignored as insomnia is generally higher in women.43, 55-58, 61, 62, 64, 66-73 In older women, with or without symptoms of depression, sleep disturbances increase with age.83 Elevated anxiety is another culprit that lowers sleep quality.84 It was reported that the female US veterans (i.e. those who had served in the armed forces on active duty for a period of 180 days or more) had a higher risk for insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing than non-veteran participants, making them more prone to cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.85, 86 Issues related to sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women, especially those coping with osteoarthritis, have yet to be fully examined.87

SLEEP, DEPRESSION, AND ANXIETY

Good quality sleep is considered a blueprint for maintaining mental health.88, 89 It is well documented that anxiety and depression are common in the aged population.83, 90 Depression in aged subjects can lead to adverse outcomes, including impairment in executive functions, medical illnesses, disability, increased mortality, and increased health services utilization.91-93 Accelerated age-related changes in sleep architecture may be linked to depressed mood in older adults.94, 95 Sleep of short and long durations are also associated with increased risk of depression in adults.96

Sleep disturbances are regarded as secondary to depression due to depression's comorbidity with sleep disorders. However, recent evidence has indicated that sleep disturbances not only precede the occurrence of depression, but are also associated with increased risk for depression cross-sectionally and longitudinally.88, 90, 94

SLEEP AND PAIN

Chronic pain is a common debilitating condition among the elderly population. A national study of Medicare beneficiaries in the USA showed that bothersome pain afflicts half of the older adults, and it increases significantly with greater disease burden.97, 98 This leads to emotional distress, thereby reducing sleep quality, which in turn can reduce pain thresholds and increase feelings of fatigue.85 In addition, symptoms of depression, fatigue, and insomnia were more severe in subjects with moderate-to-extreme pain interference than in those who reported less pain.85 Prevalence of pain and the number of pain locations are higher in older women than in men.98

SLEEP AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

Sleeping less than 4–5 h or more than 10 h per night is linked to increased mortality.99-102 A recent report on a middle-aged Chinese population found increased coronary artery disease in those sleeping less than 6 h per night.103 In a Japanese population, long sleep duration among the elderly with poor sleep quality is associated with a higher risk of mortality linked to cardiovascular disease.101 A similar trend was also observed in aged American Indians.102 According to this report, cardiovascular diseases were least prevalent among the subjects who slept for 7–8 h per night.

SLEEP AND DEMENTIA

Dementia is one the major problematic conditions in the elderly. A recent meta-analysis and detailed review indicated that sleep disturbances may predict the risk of incident dementia. Sleep-disordered breathing was a risk factor for all-cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and vascular dementia. In contrast, insomnia increased the risk for AD but not for vascular or all-cause dementia.104 Sleep disturbances are common (25–40%) in AD patients.105 Sleep problems in these patients are a serious concern as they further adversely affect the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia and also increase the risk factors associated with patients' day-to-day activities.106-110 Recent multi-centric, cross-sectional research in Japan indicated that sleep disturbances are key early symptoms of AD associated with behavioural and psychological factors.111 It was clearly evident from this elegant study that sleep disturbances were strongly associated with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in the very early stage. Very early-stage AD patients (Clinical Dementia Rating = 0.5) with sleep disturbances had significantly more behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia than those without sleep disturbances. They also had a higher prevalence of anxiety, euphoria, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behaviour. Another study found that sleep disturbances during middle age are associated with the development of dementia in later life.112 Cognitive impairment is reportedly increased in older women with sleep-disordered breathing.113

In recent years there has been substantial progress in the detection and recognition of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), which has emerged as a common and important clinical disorder. The DLB Consortium has also refined its recommendations about the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of DLB. The revised DLB consensus criteria give increased diagnostic weighting to REM sleep behaviour disorder.114

SLEEP AND PHYSICAL DISABILITY

Physical disability is yet another issue in the elderly that marks the loss of independence, as difficulty in performing activities necessary for independent living increases.115, 116 This affects sleep regardless of whether a person has assistance at home or is in a hospital intensive care unit.117-119 For those who have assistance at home, there are genuine concerns that their caregiver's sleep is also affected.120

OTHER MEDICAL CONDITIONS CONTRIBUTING TO SLEEP PROBLEMS OF OLD AGE

One study excluded subjects affected by various factors that can disrupt sleep such as poor health, primary sleep disorders, and poor sleep hygiene (e.g. irregular sleep schedules, poor sleeping environments). It found that older adults do not experience excessive daytime sleepiness and the concomitant need to nap regularly during the day.121 Nevertheless, the majority of older adults have significant sleep disturbances, which are related to a variety of causes. Physical and psychiatric illnesses, and the medications used to treat them, also contribute towards sleep problems in old age.122 The prevalence of insomnia is higher among older adults and is frequently related to an underlying medical or psychiatric condition.100, 123-128 People with insomnia often experience excessive daytime sleepiness, difficulty in concentrating, and significantly reduced quality of life. Both behavioural therapies and prescription medications are considered effective means to treat insomnia. Reports have suggested that addressing the conditions of depression and cognitive impairment in the elderly population may help improve not only their quality of life but also reduce insomnia.129, 130

Snoring, which is most commonly associated with being overweight and having anatomical alterations in the upper airway, worsens with age. Loud snoring can be a symptom of obstructive sleep apnoea, a condition in which breathing stops for as long as 10–60 s. A drop in oxygen in the blood during this period alerts the brain, causing a brief arousal (awakening) and breathing resumes. Repeated stoppages of breathing cause multiple sleep disruptions at night and can result in daytime sleepiness.47, 131

Restless legs syndrome is a neurological disorder characterized by an irresistible urge to move the limbs. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome increases with age and can make it difficult to sleep through the night. About 80% of people with restless legs syndrome also have periodic limb movement disorder. According to the National Sleep Foundation, approximately 45% of all older persons have at least a mild form of periodic limb movement disorder.132

Other medical problems can also produce sleep disorders in old age. Common medical problems such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, respiratory diseases (e.g. asthma), immune disorders, and gastroesophageal reflux disease are all associated with sleep problems.45, 46, 49, 50

NEW APPROACHES TO REMEDIAL MEASURES

Insomnia is one of the major health issues of old age. Although this review has not discussed medicines used for insomnia, it should be noted that classes on drugs that are commonly used to manage insomnia, such as benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines, can lead to several residual side-effects like drug dependence, tolerance, rebound insomnia, muscle relaxation, hallucinations, depression, and amnesia on prolonged use.133-135 Consequently, there is a persistent need to find a safer hypnotics for the treatment of insomnia. Moreover, because of the numerous challenges associated with treating the elderly, there is an increased need to avoid potentially harmful medications. Treatment with melatonin agonists has gained popularity because they have a better safety profile than sedative hypnotics that target γ-aminobutyric acid receptors.136 Traditional medicines offer a wide range of herbs and herbal products with sedative properties,137-139 some of which can be used for prolonged periods without ill effects. However, because of a lack of scientific validation, these herbs and herbal products have still not found a place in the mainstream clinical practice in sleep medicine.137, 138 So it is necessary to evaluate scientifically the hypnotic potential of the active principles of many of these herbs.140

Non-pharmacologic management of insomnia may be advisable for many elderly patients. Regular physical exercise is a simple strategy suggested for dealing with sleep problems in elders because it may promote relaxation and raise core body temperature, which could help in initiating and maintaining sleep.141 One recent report provided robust evidence for bright light therapy as a promising non-pharmacological strategy for managing insomnia in aged subjects with dementia.142

CONCLUSION

Ageing is associated with increased incidences of sleep-related ailments. Older people have difficulty in falling asleep and staying asleep due to frequent arousals. Changes in sleep patterns are a part of the normal ageing process, and their caregivers must be educated about the sleep patterns of the elderly. Awareness programmes are extremely important and helpful in dealing with the sleep problems of the elderly. Growing older does not always mean sleeping poorly, but sleeping well can certainly improve overall health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Cognitive Science Research Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology, India (SR/CSI/110/2012 and SR/CSRI/102/2014).