Narrative power in the narrative policy framework

[Correction after first publication 26 May 2025: Reference was added to Blum et al., Introduction to the special issue.]

Abstract

enThe Narrative Policy Framework lacks clear and empirical explanations of power. Yet, the study of narratives is inherently the study of power in shaping policy outputs and decisions. We develop a conceptual model positing that expressions of power (power to, with, and over) may be discovered in narrative constructs (e.g., narrative structure, communication forum). We suggest that the dilemma of measuring the “unobserved” in power may be addressed methodologically using a counterfactual (e.g., experiment, comparative study). Finally, we uphold the use of keystone NPF variables (e.g., policy decisions, attention) as proxy measures of the outcomes of narrative power in the policy process. Taken together, this model advances the operationalization and measurement of narrative power in the policy process.

摘要

zh叙事政策框架在权力方面缺乏清晰且实证的解释。然而, 叙事研究本质上是研究权力在影响政策产出和决策过程中的作用。我们提出一个概念模型, 假设权力的表达方式(权力行使、权力合作、权力支配)能在叙事建构(例如叙事结构、传播论坛)中被发现。我们认为, 反事实方法(例如实验、比较研究)能从方法论上应对一个困境,即如何衡量权力中“未被观察到”的方面。最后, 我们支持使用关键的叙事政策框架变量(例如政策决策、注意力),将其作为“叙事权力在政策过程中的结果”的替代指标。总而言之, 该模型推进了叙事权力在政策过程中的操作化和衡量。.

Resumen

esEl Marco de Políticas Narrativas carece de explicaciones claras y empíricas del poder. Sin embargo, el estudio de las narrativas es inherentemente el estudio del poder en la configuración de los resultados y las decisiones políticas. Desarrollamos un modelo conceptual que postula que las expresiones de poder (poder para, con y sobre) pueden descubrirse en constructos narrativos (p. ej., estructura narrativa, foro de comunicación). Sugerimos que el dilema de medir lo “no observado” en el poder puede abordarse metodológicamente mediante un contrafactual (p. ej., experimento, estudio comparativo). Finalmente, defendemos el uso de variables clave del Marco de Políticas Narrativas (p. ej., decisiones políticas, atención) como indicadores indirectos de los resultados del poder narrativo en el proceso de formulación de políticas. En conjunto, este modelo promueve la operacionalización y la medición del poder narrativo en el proceso de formulación de políticas.

The founding father of the policy sciences, Harold Lasswell, defined politics as “who gets what, when, and how” (Lasswell, 1936). Consequently, individuals and groups with the ability to influence such resource distribution dynamics are said to wield political power. Philosopher Bertrand Russell goes even further to place the study of power at the center of all social science: “The fundamental concept in social science is Power, in the same sense that Energy is the fundamental concept in physics” (Russell, 1938, p. 10). Policy scientists have since devoted considerable attention to explaining how policy actors obtain and use this power, as well as what effects the exercise of power has on policy outputs and outcomes. Indeed, some policy process scholars argue that “the study of policy process is ultimately the study of political power” (Smith & Larimer, 2018, p. 94). Yet, despite this long-standing recognition that power is a central concept, power remains a largely under theorized and operationalized concept in the policy process literature.

This lack of clarity is particularly problematic for the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), which, at its core, is concerned about the ways in which power is expressed through narratives (Jones et al., 2023). The NPF is grounded in the assumption that individuals, as homo narrans, conceptualize and process information in narrative form, which means that storytelling pervades—and shapes—virtually every social and political context, from the household to the workplace to the voting booth. The NPF is specifically interested in how narratives influence the trajectory of the policy process at various stages of policy making and across micro, meso, and macro levels. Thus, power in the policy process can potentially be illuminated in the study of policy narratives that the NPF claims shape the policy landscape.

Recent NPF scholarship has begun to work toward conceptualizing and operationalizing power, but much work remains. Most notably, Sievers and Jones (2020) challenged the policy process community—and NPF scholars specifically—to more precisely define what power means and how to measure it. While measuring narrative effects in the policy process is familiar territory for NPF studies, we address their challenge theoretically by conceptualizing narrative constructs (e.g., elements of form, content, narrator, venue of dissemination) in terms of the expression and impact of power. As such, we begin with a two-pronged premise. First, we assume policy actors are the entities who hold power in the policy process. Second, one way policy actors may wield power is through the use of narrative constructs, with the intention to affect some outcome (e.g., attention, motivation, behavior, policy choices, policy preferences). We call this phenomenon narrative power.

To advance the study of power in the policy process broadly, and in the NPF in particular, we begin by discussing the broader literature on narratives and power in the policy process. We summarize Sievers and Jones' (2020) critique of policy studies' lack of attention to power, as well as their suggested approach that leverages Lukes' (1974) theory of power and anchors power in the NPF to “beliefs.” We then outline a two-fold adaptation of Sievers and Jones' (2020) proposition that is grounded in addressing the challenges inherent in empirical assessment of power. In doing so, we make three distinct but interrelated contributions to the emerging scholarship on power and the NPF. First, we suggest that in lieu of choosing one single theory of power e.g., Lukes' (1974) elitism, Dahl, (1961) pluralism, NPF scholars could ground their inquiry of narrative power to the broader—and frankly more flexible and accessible—underlying conceptual elements that appear across several theories, namely the expression of power (power with, power to, and power over). Second, we argue that by refocusing attention on the expression of power, as opposed to a singular theory, NPF scholars will be better positioned to assess the contextual dynamics of narrative power, namely the ways in which certain actors are able to strategically manipulate or influence power in some contexts but not others. Lastly, we contend that incorporating counterfactuals (e.g., survey or natural experiments, comparative case studies) in NPF research designs provides a promising avenue for empirically evaluating the practical implications of these abstract theoretical elements of power real world contexts. We then present a conceptual model of narrative power in the NPF that posits the use of narrative constructs to observe and measure expressions of (or the absence of) power, as well as ways the outcomes of such expressions of power can be observed in the policy process.

POWER IN THE POLICY PROCESS

The idea that narratives and power are inextricably linked is hardly a revelation. For decades, policy scientists have emphasized the ways in which narratives and their content can both undermine and reinforce existing power structures. Schattschneider (1960) famously argued that “the definition of alternatives is the supreme instrument of political power” (p. 64), suggesting that groups who present and frame a policy idea in a way that resonates in a particular moment could gain power over the policy agenda. Rochefort and Cobb (1993) echo Schattschneider's assertion, writing “Actions speak louder than words, it is commonly said. However, in the world of politics and policymaking, this is not necessarily so, and in any case the two are inextricable; action and words influence and even stand for each other as the embodiment of the ideas, arguments, convictions, demands, and perceived realities that direct the public enterprise” (p. 27). And, in her groundbreaking book Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, Stone (2012) remarked that power in the polis is often expressed through narratives or what she calls the portrayal of different ideas, noting that “Political fights are conducted with money, with rules, with votes, and with favors, to be sure, but they are conducted above all with words and ideas” (p. 36). Thus, many of the foundational texts in the policy sciences suggest that narratives, political language, issue framing, problem definition, and agenda setting are important vehicles for expressing power.

Yet the NPF and, for that matter, virtually every theory of the policy process, has ignored operationalizing the concept of power, largely for two reasons detailed by Sievers and Jones (2020). First, power seemingly defies a universally accepted definition and is, therefore, difficult to measure because it is hidden, intangible, and hard to observe as it is often manifested in concepts like charisma, moral authority, and trust. Second, despite recent work extending the policy process research to non-democratic regimes, traditional theories of the policy process were developed in western contexts that assume some form of pluralism, meaning that unarticulated, normative assumptions of power are rife throughout them. However, in contrast to this lack of attention to power in the policy process theories, several explicit theories of power have emerged from political theory, political science, and public administration literatures: Lowi's arenas of power (Lowi, 1971); Follett's (1926) power in organizations; Arendt's (1970) distinction between power and violence; Dahl's (1961) pluralist perspective; Morriss' (1987) power as ability; Lukes' (1974, 2005b, 2021) and Bachrach and Baratz (1962) dimensional approaches to capture unobservable phenomena; and, more recently, the putatively marginal effects of the American public on public policy (Gilens & Page, 2014), alongside a host of others (see Pansardi & Bindi, 2021). As such, while power may be a common, albeit ephemeral, concept in the policy process literature, there are many theories of power in sister disciplines that can help to inform its conceptualization. And yet, choosing one theory of power is a nontrivial and consequential task, since empiricism is guided by operationalization of the concepts that populate the theory.

Undeterred by these theoretical and empirical barriers to power in policy scholarship, Sievers and Jones (2020) offer a path forward for the policy sciences. They begin by critiquing the field of policy studies for its propensity to rely on measuring observable elements of the policy process (e.g., policy decisions, participation in policy subsystems, agenda setting) while assuming a pluralistic democracy premised on accessibility, free participation, ease of petition, and manifest decisions. As such, those who lack power are implicitly excluded in many analyses because they tend to be absent from observable elements of the policy process, especially in ex ante studies. To address this weakness, Sievers and Jones (2020) leverage Lukes' (1974, 2005b) conceptualization of power, which was articulated, in part, in response to definitions of power grounded in pluralism that presumes the policy process as an open and relatively even-footed competition between various organized interests, as exemplified in Dahl's (1967) and Truman's (1971) scholarship.

In brief, Lukes (1974) proffered three dimensions of power. The first dimension, decision making, focuses on open interest conflicts in policy debates, in which there are discernible winners and losers. Power in this dimension is active and observable. Grounded largely in Dahl's (1961) work, Lukes argues this dimension does not consider unequal power structures. He identifies a second dimension of power, leveraged during agenda setting, which is informed by the work of Bachrach and Baratz (1962). In this dimension, elites use power to exclude non-conforming interests and groups from the agenda setting process. While this dimension is about elites limiting the scope of what is debated, there remains an identifiable and observable interest that is suppressed. Both the first and second dimensions relate to (a) known stages in the policy process and (b) conflicts of interests among individuals and/or groups.

Conversely, Lukes' third dimension of power considers the use of power that is unobservable, specifically the ability of elites to avoid conflict altogether by shaping peoples' thinking in what he called “domination.” Lukes' primary interest was this third dimension, where the expression of power is aimed at securing the willing compliance from people, even when such acquiescence is not in their own interest. This elite orientation of Luke's theory of power, similar to other scholars such as Murray Edelman (1967, 1971), was born in the context of the politically tumultuous U.S. context of the 1960s and 1970s, a time imbued with distrust of the government's use of power to act in the public interest. Thus, Lukes' third dimension assumes an elite theory of democracy e.g., Lowi's, (1979) end of liberalism; Mills', (1956) “power elite” that posits that political elites hold and express power at the expense of individual and collective interests, or power over. In its most successful form, from the perspective of those in power, dominant power yields what social psychologists and others describe as quiescence (Fiske, 1993; Gaventa, 1980; Keltner et al., 2003), in which large masses of people are unable to frame their own interests, much less organize to promote their interests.

Informed by Lukes, Sievers and Jones (2020) criticize the operational measures of power in the NPF and other policy process theories given the reliance on observed phenomenon, thus ignoring the unobservable or those non-leaders and non-decisions that reside outside of policy debates. The conundrum Sievers and Jones (2020) puzzle through is how to measure something that is not there, something that is not observable. They suggest that Lukes' (1974) third dimension of the unobservable power over in the policy process may be empirically ascertained through a comparison of “beliefs” in macro and meso elite policy narratives with that of disadvantaged target populations' policy narratives at the micro-level. Sievers and Jones (2020) fashion “beliefs” to be a proxy for these target populations' “true interests.” Exploring the absence of decisions, participation, and narratives, they say, will uncover expressions of domination or power over.

We agree with Sievers and Jones (2020) that bringing to bear explicit theories and operationalizations of power to the policy process may alter or advance policy studies writ large. In lieu of choosing one theory, however, we suggest using the concepts that define different expressions of power, namely power to, power with, power over. These concepts are widely used across multiple theories of power (Follett, 2013; Lukes, 1974, 2005a; Morriss, 1987), allowing for a potential convergence of conceptual applications in policy process research. Moreover, focusing on expressions of power has the added benefit of providing concepts that are more amenable to reliable operationalization. In a comprehensive documentation of the evolution of the study of power across time, Pansardi and Bindi (2021, p. 51) offer concise definitions of these three ubiquitous expressions of power. Power to is defined as the ability of an individual to achieve certain outcomes, to shape their life, to make a difference. Power with is defined as a collaborative/shared form of power, capturing individuals' ability to act together in the spirit of collective outcomes or goals, to build bridges across diverging interests. This aligns most clearly with empowerment models where power is shared in decision making. Finally, power over is defined as a reflection of an asymmetrical relationship between a singular actor or groups of actors, whereby one exerts influence over the other, sometimes against the latter's will or interest. Decision making is characterized by control and self-interest. These expressions of power expand beyond single stages of the policy process and conceptually capture elements of power that are both observed and unobserved.

Given our assertion that the expression of power (to/with/over) is a plausible operational definition of power, we now seek to advance Sievers and Jones' (2020) empirical propositions in two ways. First, we reconsider the role of the counterfactual in measuring the unobserved. By definition, counterfactuals are a way to explore outcomes if the intervention or phenomenon under study did not occur. Counterfactual reasoning is thinking about alternative scenarios if some event did or did not happen; for example, what would have happened if Biden stayed in the 2024 Presidential race? In science, counterfactual conditions are those whereby there is an absence of whatever is being studied. In the case of power, for example, experimental social psychologists often employ laboratory-based manipulations to examine the effect of high power as compared to the counterfactual of low or no power on human behavior and decision making through role-playing scenarios where participants are randomly assigned to different positions of power (e.g., manager, subordinate), given amounts different resources, or provided different structural positions in a room (e.g., head of table) (Cho & Keltner, 2020). Thus, with the use of counterfactuals in empirical research (both qualitative and qualitative), researchers are able to determine causal effects by comparing differences (the delta) between the observed (presence of power) and the unobserved (absence of power).

Determining what constitutes a counterfactual is crucial to the validity of scholarship through greater accuracy in assessing causal relationships. Thus, it is critical for researchers to be transparent about how/why the criteria they chose to determine the counterfactual demonstrates the absence of power. For example, Sievers and Jones (2020) rely on Gaventa's work on power (Gaventa, 1980, p. 29) and posit that the procurement of policy narratives from non-elites or disadvantaged target populations outside the policy subsystem can serve as the counterfactual. While this is a possible example of a counterfactual, we question the author's criteria of “outside the policy subsystem” as a realistic situation in which power does not occur. The counterfactual would be that if power in the subsystem were not exercised, then target populations would act in their own interest. Yet, disadvantaged target populations may be outside of the subsystem precisely due to the power exercised within the subsystem that intentionally or inadvertently excludes them; this potentially introduces endogeneity into measurements of and how/if power is wielded. In this case, Sievers and Jones' (2020) proposition may not always function as a proper counterfactual as it may not analyze the complete absence of the exercise of power, but rather how populations act that may have already been marginalized by those in power. Thus, while we whole-heartedly agree that the use of a counterfactual (in qualitative; Reichardt, 2022) and quantitative (Bours, 2021 approaches) is critical to the empirical analysis of power, we encourage a careful consideration of exactly what situations serve as appropriate counterfactuals and why.

Second, we concur with Sievers and Jones (2020) that analyses of power must satisfy scientific rigor in additional ways. The authors' proposed analysis of “beliefs” is systematic and may be useful when overarching belief systems are fairly well-crystallized and known. However, we question how this approach holds up in situations where belief systems are more dynamic and less observable, such as in nascent subsystems (Wiedemann & Ingold, 2024), or where institutions are designed to encourage actors with diverse beliefs to reach consensus (Koebele & Crow, 2023). Moreover, while elites' beliefs about a particular policy issue may be shared by actors outside of established coalitions within the subsystem or even completely outside of the subsystem, they may diverge on more macro beliefs such as those about who should be involved in decision making, potentially explaining why some actors are marginalized beyond the bounds of the subsystem to begin with. Indeed, the Advocacy Coalition Framework's tripartite belief structure suggests that actors sharing beliefs on some level may diverge on others (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Shanahan et al., 2013), and that actors with divergent beliefs may still choose to work together for other reasons, including the ability to gain power (Koebele, 2020). Analyses of these divergent “beliefs” will lead to different interpretations of the expression of power over, prompting the subjective question of which “belief” is the “best” comparison and represents the “true interests” of each group of actors. Thus, while the pursuit of the NPF concept of “beliefs” may be promising in the NPF study of power, it may, in some instances, fall short of satisfying scientific rigor, as the choice of which belief systems to measure is ultimately consequential to inference.

In sum, Sievers and Jones raise excellent questions about power and policy process theories that should continue to be advanced conceptually and tested empirically. Here we build on their discussion of power in the NPF and address our critiques by presenting a model of narrative power that pulls into alignment narrative constructs with operational definitions of power (to/with/over) and empirical outcomes of narrative power.

NARRATIVE POWER IN THE NPF

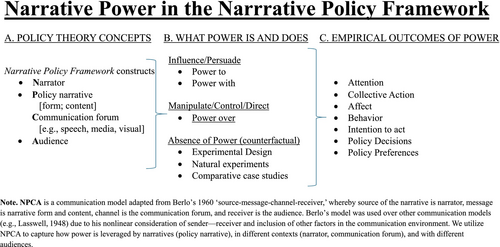

In this section, we propose a model to conceptualize and operationalize narrative power in the NPF based on three broad and interdependent categories: policy theory concepts, expressions of power, and empirical outcomes of power (Figure 1). We purport that (A) the core policy theory concepts of the NPF are narrative constructs (e.g., elements of form, content, narrator, forum of dissemination), which serve as a vehicle through which policy actors wield power; (B) how policy actors' expressions of power (to/with/over) reflect what this power does (e.g., persuade, manipulate) and may be observed when compared to the absence (counterfactual) of this power in experimental designs, natural experiments, comparative studies, etc.; and (C) the empirical outcomes of narrative power are derived through NPF's keystone outcome measures, including issue attention, policy preferences, and policy decisions (Figure 1). We theorize that narrative constructs (A) may strategically contain some expression of power (B) that results in a narrative effect (C). This model applies to the study of narratives at any level of analysis: micro, meso, or macro. We describe these three categories of our conceptual model in detail below.

Policy theory concepts

Alongside traditional measures of power such as resources and access, assessments of power in policy process theories are necessarily anchored in policy theory concepts. For example, the Advocacy Coalition Framework focuses on the power of coalitions (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993), and the Multiple Streams Framework assesses the power of policy entrepreneurs (Zahariadis et al., 2023). When considering the power of narratives, the most frequented terrain in the NPF literature features the policy narrative itself—its form (e.g., characters, setting, plot, and moral) and content (e.g., strategies and beliefs). Yet, there are a host of other NPF narrative constructs that fall outside of these two categories that are cited as important to the power of narratives (Jones et al., 2023) but receive minimal attention, including the narrator, audience, and communication forums (e.g., newspaper, X, website). The classic exposition of communication in David Berlo's (1960) source-message-channel-receiver model illustrates this relationship between narrator (source), narrative form/content (message) and the broader narrative environment (channel and receiver). Due to his nonlinear conceptualization of sender—receiver and inclusion of other factors in the communication environment, we employ Blum et al.’s (forthcoming) adaptation of Berlo's model to Narrator, Policy narrative, Communication forum, and Audience (NPCA, Figure 1a and figure note). This model serves as an organizing heuristic, bringing together in one place the different constructs that the NPF has described since its inception.

Narrators craft the point of view of a story. Examinations of the power of the narrator have gained attention in recent NPF scholarship (Costie & Olofsson, 2022; Hand et al., 2023). Given the NPF narrator trust hypothesis, most studies assess the power of the narrator to persuade individuals contingent on the extent to which the audience trusts the narrator (Ertas, 2015; Lybecker et al., 2022). Results have been mixed regarding the power of the narrator, especially in contrast to studies that include tandem effects of narrative form and content. Regardless, the role of the narrator in the NPF is largely undertheorized. For example, the power of the narrator in other literatures is measured through multiple dimensions, including demographic features such as gender identity (Witus & Larson, 2022), age (Oakes & North, 2011), political affiliation, cultural background, or profession (Faour-Klingbeil et al., 2021), values/beliefs, communication skills (e.g., charisma), and narrator point of view (Chen & Bell, 2022). In his seminal work on influence, Cialdini (2007; 2021) identified that narrators who are perceived to be in positions of authority as well as those who share a common identity with the audience are key factors that increase the persuasiveness of messages.

Importantly, the narrator in policy narratives has three potential functions of power. First, the narrator may be a policy actor who wields power (to/with/over) through narrative construction and choice of communication forum, as discussed further below. Political entities, interest groups, and the like pen policy narratives to affect policy change or maintain the status quo. Second, a narrator often casts himself/herself/themselves as a character in the policy story (usually the hero or victim), effectively becoming a narrative element intended to activate some outcome (e.g., affect, motivation, collective action, behavior). Third, many narrators are both a policy actor exercising power and a narrative element, the vehicle through which power is used toward some intended end (persuasion, attention, etc.).

Continuing with the NPCA, central to the study of power in the NPF is the Policy narrative. The two most current chapters on the NPF, one on the framework itself (Jones et al., 2023) and one on NPF methods (Jones et al., 2022), offer the most current and comprehensive listing of references to the myriad NPF studies on policy narratives. Form and content contain the primary NPF constructs upon which scholars focus. Narrative power is exercised through the strategic use of form and content that capture target audience attention and affect, effectively transporting them into the narrative (Shanahan et al., 2019). For example, hero characters are known to be persuasive and therefore a powerful vehicle for policy actors to use in constructing policy narratives, in contrast to victim-centered narratives which are not typically found to be as engaging and thus persuasive (Raile et al., 2022). Additionally, an emerging substream of NPF research has sought to expand beyond written and spoken policy narratives to include narratives conveyed in the form of pictures (Boscarino, 2022), videos (Lybecker et al., 2015), and visual policy narratives or narratives embedded within visual stimuli (Shanahan et al., 2023). These various forms through which policy narratives are presented may also be associated with narrative power.

Communication forum describes the context or venue in which a narrative is presented. NPF researchers have explored narratives in a variety of contexts including national policy making institutions (Jacobs & Sobieraj, 2007; Jones & McBeth, 2020), state and local policy making institutions (Chang & Koebele, 2020; O'Donovan, 2018), public hearings (Colville & Merry, 2022) and various types of media (Blair & McCormack, 2016; Crow, Berggren, et al., 2017; Crow, Lawhon, et al., 2017; Shanahan et al., 2011). On the whole, the communication forum has rarely been central to the study of narrative power (with some exceptions, Shanahan et al., 2008). Yet, as a mechanism for policy actors to reach target audiences, communication forum choice can be critical given the potential to reach larger audiences (e.g., nationwide networks) or provide more sophisticated dissemination tools (e.g., digital media with access to billions of users). The power of communication forum for a policy narrative to gain attention and influence the policy discourse is ripe for studies of narrative power.

Audience, while a critical part of any evaluation of the power of narratives, also receives little attention in NPF studies. Audiences, often referred to as “target audiences,” are typically just named rather than empirically determined in terms of who consumes the policy narratives. Recently, Colville and Merry (2022) and Lybecker et al. (2022) elevate the importance of the narrator–audience experience by analyzing the interactive effects of trust, beliefs and policy preferences between these narrative mechanisms. In the context of narrative risk communication, situating the audience as the hero is found to be effective at increasing risk preparation (Raile et al., 2022) and could be one potential exercise of power by policy actors. Simply put, policy narratives without an audience are absent of narrative power. Research on social interactions reminds us that the power or lack of power of the audience is also a powerful dimension for understanding potential effectiveness of narratives (Fiske & Berdahl, 2007).

In sum, the study of power in the policy process begins with the concepts that populate policy theory, as it is through the engagement with these concepts that policy actors are theorized to wield power. With the NPCA model, we encourage NPF scholars to consider a wider array of NPF constructs beyond form and content to study narrative power. The next part of our model proposes how to think about these narrative constructs in the context of power.

What power is and does

While political actors hold power, the NPF is primarily interested in how they exercise that power through the use of narrative constructs (Figure 1b). But, how do we assess this exercise of power in narratives? Here, we rely on the work of social psychologists (Fiske & Berdahl, 2007), who link what power is—expressions of power (to/with/over)—with what power does (e.g., persuade, manipulate). For example, power that persuades is akin to power to or the ability for a person to accomplish what they set out to do. For the NPF, persuasive narrative risk messages activate power to in individuals to engage in risk reduction behaviors by situating the audience as the hero (Raile et al., 2022). Similarly, power as influence is associated with power with, or acting together toward a communal goal. Such power may be present through the use of a communal communication forum that enables different narrative perspectives to be heard to solve a problem (Koch et al., 2021). Finally, power as manipulation, control, or directive is associated with both the traditional understanding of power over as dominance (Lukes, 1974) and a zero-sum game of winners and losers (Follett, 1973), as well as relationships based on consent that also include a hierarchy, such as those with expertise (e.g., parent, teacher), formal decision-making authority (e.g. elected officials), or those in command (e.g., symphony, military) (Chang & Koebele, 2020; Lukes, 2005b; Pansardi & Bindi, 2021). For the NPF, the expression of power over could be assessed through the role of the narrator, whereby dominance may be seen when a command-and-control regulatory agency is cast as the narrator (e.g., Food and Drug Administration), or a consensual hierarchy may be seen when a doctor (the expert) providing health advice is cast as the narrator. In all, NPCA policy concepts contain the critical characteristics of what power is and what power does.

To measure what power is and does through NPF constructs requires some rationale (usually theory based). For example, consider narratives around vaccination uptake. An NPF researcher may test the power of the narrator on intent to get vaccinated, hypothesizing that a narrator who is your doctor is an expression of power within this context of shared decision making in clinical practice. Put differently, the narrator (your doctor) is providing the receiver of the narrative (the patient) information that may or may not change their behavior in this rather intimate context. Conversely, the CDC (yet another narrator) may be considered power over, given that they frequently disseminate information through top-down, directive-like nature of communication. The CDC may implore the receivers of their narratives to “get vaccinated” through outreach campaigns, but these communications are effectively a one-way street.

To truly measure the exercise of power, a counterfactual is necessary. In experiments, the control condition serves as a counterfactual, as it enables researchers to measure the effects of the intervention (in this case, power) in the absence of the intervention (Bennett, 1987). In the example of narrator power, the counterfactual would be the absence of the narrator in the vaccine message delivery (e.g., receiving direct and personalized health advice from a doctor versus reading the same message in a magazine). Other examples of researchers using counterfactuals in their design include natural experiments and comparative case studies. Counterfactuals—in whatever form the researcher chooses—allow for heightened validity in interpreting the effect of what power is and does.

Empirical outcomes of power

Political actors leverage power to shape the policy process at all stages (Figure 1c). In this category of our model, we focus on the effects of the expressions of power and what it does on outcome measures of narrative power, which occur at various times in the policy process and at any level of analysis (micro, meso, macro). These core NPF response variables are well articulated and operationalized and include attention (Peterson, 2018), affective responses (Shanahan et al., 2019, 2023), behavior (Shanahan et al., 2023), collective action (Esposito et al., 2024), intention to act (Raile et al., 2022), policy solutions (Crow, Berggren, et al., 2017; Crow, Lawhon, et al., 2017), and policy preferences (Jones, 2014). We argue that these keystone outcome measures are not only appropriate in the assessment of the narrative power, but they are also necessary to define and assess repeatable and valid measures. Importantly, measuring effect size in comparison to a counterfactual (e.g., control condition for a micro-level experimental study or natural experiment for a meso-level case study) instills the validity of the measure of narrative power.

Much NPF scholarship assesses the narrative effects of narrative constructs on NPF keystone outcome variables. However, empirically connecting (A) NPF constructs to (B) expressions of power and then to (C) narrative outcomes is simply unexplored terrain for NPF researchers. Such future studies will illuminate power dynamics in the narrative environment and significantly contribute to understanding policy change and stability/stasis. For example, are particular narrative effects, such as collective action and attention, associated with power with and power to, respectively? Do certain character types, such as the villain, tend to exercise expressions of power over, or are these expressions of power through characters context dependent? Are settings—where the action takes place—a heuristic for power, e.g., a courtroom is an expression of power over, whereas a community meeting room is power with? We encourage NPF scholars to develop and test power-centered NPF research questions that connect narrative constructs, expressions of power, and narrative effects.

In sum, our model of narrative power in the NPF advances the study of power in three ways. First, it takes into account the entirety of the narrative environment (NPCA) as potential sources of power, thereby establishing a more comprehensive approach to narrative power. Second, it asserts the utility of the power to/with/over expressions as reliable constructs of power that are embedded in multiple theories of power. Third, because these expressions of power may be understood or measured in narrative constructs, the model creates a replicable pathway between narratives and power. Finally, the model offers an empirical solution by asserting the use of the counterfactual to measure the effect of power on narrative outcome variables.

CONCLUSION

Despite being an increasingly popular area of study in policy process research, the concept of power has remained under-articulated and ill-defined in the policy process literature, a testament to the challenges associated with conceptualizing and measuring such an abstract and deeply contextual concept. And yet, if the study of policy narratives is the study of one form of power in the policy process—which we term narrative power—how can we meaningfully and rigorously come to understand it across levels of analysis and contexts? We answer this question by bridging policy theory and concepts of power to demonstrate one way to operationalize narrative power in the policy process.

This approach begins with the assumption that policy actors, who are often political elites, hold political power and exert such power through the use of narrative constructs (narrator, form/content etc.; Figure 1a). To test the power of these mechanisms, we suggest theoretically anchoring definitions of narrative constructs to the concept of expressions of power (to, with, over; Figure 1b), which are leveraged in multiple theories of power. Indeed, our model of narrative power in the policy process can be integrated into other theories of the policy process through an examination of how power is leveraged in key policy concepts such as coalitions (ACF), policy entrepreneurs (MSF), or within formal and informal institutions (IAD).

For the NPF, the vast majority of studies examine the policy narrative itself through form and content, while much less attention is paid to the narrative environment external to the policy narrative—that of the narrator, communication forum, and target audience. We suggest the use of the NPCA model (Blum et al., forthcoming) in assessing narrative power, including a much wider range of NPF concepts, thus identifying the potential pathways through which power is wielded.

We also contend that the empirical measurement of the power of narrative concepts rests on methods that include a counterfactual in which narrative power is measured against the absence of narrative power (the unobserved) to determine the size of the effect. Although manipulated power and control conditions offer experimental counterfactuals, natural experiments and comparative methods also provide potentially fruitful approaches since they allow comparisons to be made between a policy passing in one context and failing in another (the negative case or counterfactual). Similarly, thought experiments may also consider the absence of power but are less empirical and more philosophical in nature.

Additionally, locating the concepts of power to, power with, and power over in specific elements of NPCA constructs may advance the study of narrative power. For example, expressions of power may be linked to characters (villains may be linked with power over; heroes may be reflective of power to or with) or settings (a courtroom may be linked to power over, whereas a community center may be power with). The effect of these expressions, we propose, is found in keystone NPF variables that reflect the ultimate goals of the policy elite in crafting policy narratives: narrative attention, affective response, motivation to do something, support for the elite's policy preference, and, ultimately, uptake of a prescribed behavior or policy.

We acknowledge that qualitatively assessing the larger and perhaps unobserved context in which power is being expressed is of immense value. When operationalizing any theoretical concept empirically, some amount of theoretical robustness is lost. This phenomenon occurs across policy process theories. For example, the operationalization of concepts such as policy entrepreneurs in the MSF and policy core versus deep core beliefs in the ACF sacrifices nuance and dimensionality for precision in measurement. Research should remain sensitive to the myriad of contextual factors shaping the expression of power across time and space regardless of their methodology. While experiments are unrivaled in their ability to correct and control for these exogenous factors, this necessarily means we are limited in our ability to directly observe the effect of context and the degree to which various spatial and temporal factors affect the expression of power.

From Lasswell to Lowi to Lukes, virtually all of the foundational studies across time in the policy sciences emphasize the centrality of power in the policy process. Yet, despite incredible advances in both the theoretical and empirical study of public policy, policy process research continues to lack a satisfactory conceptual and operational definition of power. Indeed, one could argue the pursuit of greater scientific rigor within policy sciences has caused the discipline to drift away from the power-laden assumptions of early researchers, not because they are wrong or inaccurate but because they are simply too difficult to capture. In this vein, we offer a modest first attempt to outline a conceptual and operational approach for narrative power. We bridge the gap between the theoretical and empirical by linking narrative constructs to the cross-cutting concepts of expressions of power (to/with/over), thereby abandoning the need to choose among conflicting and restrictive power theories. Moreover, the use of counterfactuals in empirical measures of narrative power is a clear pathway to assess the effects of narrative power on keystone outcome variables. The next steps to advance power in the policy process entail application to specific policy contexts, to test drive how narrative power is expressed, by whom, in what context, and to what end.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We offer our deep gratitude to reviewers for their persistence in asking us to think more deeply and precisely about how researchers can apply this model of narrative power empirically.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Biographies

Elizabeth A. Shanahan is a professor of Political Science at Montana State University where she teaches courses in public policy and administration, the Narrative Policy Framework, and applied statistics. Her research interests center on the role of narratives in policy conflict and decision making, particularly in the context of emerging infectious disease and One Health. She is a fellow in the National Academy of Public Administration and a Fulbright Scholar.

Rob DeLeo is an associate professor of Public Policy at Bentley University. His research explores the political dynamics of agenda setting and policy change in anticipation of emerging hazards as well as the governance of public risks. He teaches courses on public policy making, state and local government, and research methods.

Elizabeth A. Koebele is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Reno. She studies water policy and management in the western United States, with a focus on understanding the impacts of collaborative policy-making processes on governance and environmental outcomes. She also teaches about the policy process and co-edits the scholarly journal Policy & Politics.

Kristin Taylor is a Professor of Political Science and the Charles H. Gershenson Distinguished Faculty Fellow at Wayne State University where she teaches courses in public policy and environmental politics. Her research focuses on the role of risk and crises in the policy process, particularly agenda setting, policy entrepreneurship, and policy learning. She co-edits the journal Policy & Politics.

Deserai Anderson Crow is a Professor of Public Affairs in the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado Denver. She researches state and local policy, particularly focused on environmental and public health hazards and disasters. She teaches courses on research methods, the policy process, and disaster policy.

Danielle Blanch-Hartigan is the Chester B. Slade Professor of Psychology in the Department of Natural and Applied Sciences and the Executive Director of the Center for Health and Business at Bentley University. Her interdisciplinary research in psychology and public health aims to improve the patient care experience through better communication with healthcare providers.

Elizabeth A. Albright is the Dan and Bunny Gabel Associate Professor of the Practice at the Nicholas School of the Environment and Duke University. Albright, a mixed methods scholar, studies policy and behavior change in response to disasters, including extreme climatic events and pandemics.

Thomas A. Birkland is a Professor of Public Policy in the School of Public and International Affairs at North Carolina State University. He has studied the politics of natural hazards and technological accidents for more than 30 years. Before joining NC State, he was an associate professor of public administration in the Nelson A. Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy at SUNY-Albany.

Honey Minkowitz is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Administration at the University of Nebraska–Omaha. She earned her Ph.D. in Public Administration from North Carolina State University. Her research focuses on the policy process, policy communication, governance, and leadership.