HKT sodium and potassium transporters in Arabidopsis thaliana and related halophyte species

Edited by R. Deshmukh

Abstract

High salinity induces osmotic stress and often leads to sodium ion-specific toxicity, with inhibitory effects on physiological, biochemical and developmental pathways. To cope with increased Na+ in soil water, plants restrict influx, compartmentalize ions into vacuoles, export excess Na+ from the cell, and distribute ions between the aerial and root organs. In this review, we discuss our current understanding of how high-affinity K+ transporters (HKT) contribute to salinity tolerance, focusing on HKT1-like family members primarily involved in long-distance transport, and in the recent research in the model plant Arabidopsis and its halophytic counterparts of the Eutrema genus. Functional characterization of the salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway and HKT1-type transporters in these species indicate that they utilize similar approaches to deal with salinity, regardless of their tolerance.

Abbreviations

-

- Asn

-

- asparagine

-

- Asp

-

- aspartic acid

-

- CBL

-

- calcineurin B-like

-

- CIPK

-

- CBL-interacting protein kinase

-

- HKT

-

- high-affinity K+ transporter

-

- Ser

-

- serine

-

- SOS

-

- salt overly sensitive

Introduction

Among abiotic stresses, soil salinity constitutes a major factor in reducing crop productivity and yield (Munns et al. 2012, Zorb et al. 2019). The accumulation of salt in the soil of areas used for crop production, often irrigated with underground water, has developed into a major problem, limiting the growth and productivity of many important crops. The majority of crop plants are salt sensitive and unable to adapt to the stress factors associated with the increasingly elevated levels of salts in the soil, including ionic, osmotic and oxidative stresses, resulting in economic losses and societal disruptions. In saline soils, the ability of plants to grow, flower and develop seeds or fruits is severely compromised in a concentration-dependent manner. As a consequence, there is a strong interest in studying mechanisms of salinity tolerance in plants.

High salinity leads to osmotic stress, sodium ion-specific toxicity, nutritional deficiencies and oxidative stress (Shabala 2013, Zhu 2016, Isayenkov and Maathuis 2019) with inhibitory effects on physiological (e.g. photosynthesis inhibition), biochemical (e.g. protein stability and quantity) or developmental (e.g. retarded flowering) pathways (Li et al. 2007, Chaves et al. 2009, Kim et al. 2013, Hanin et al. 2016, Silveira and Carvalho 2016). For most plant species, Na+ toxicity is the main growth inhibitory factor (Munns 2002) at least in part because of the physicochemical similarities of Na+ with the macronutrient potassium (K+), which results in the displacement of K+ from the cellular milieu. However, Na+ ions, due to their rigid hydration shells compared to K+, has limited ability to replace K+ as the coordinating ion of proteins (Benito et al. 2014). Consequently, plants try to maintain a low Na+/K+ ratio in their cytosol, and the magnitude of this ratio is often used as a proxy to estimate the intensity of the salinity stress and the salt tolerance of plants (Shabala and Pottosin 2014). To cope with increased Na+ in soil water, plants have evolved biochemical resources and signaling pathways to restrict Na+ influx, re-export to counteract the un-avoidable influx of Na+, redistribute the ion through the plant organs via the xylem and to compartmentalize Na+ into vacuoles in various tissues (Qiu et al. 2002, Kim et al. 2007, Møller et al. 2009, Oh et al. 2009, Shabala 2013, Maathuis 2014). Moreover, K+ uptake in the presence of high external Na+ concentrations is equally crucial to preserve the supply of this essential nutrient (Assaha et al. 2017, Raddatz et al. 2020, Rubio et al. 2020). Na+ influx depolarizes the plasma membrane, leading to K+ efflux via depolarization-activated outward rectifier K+ channels (Demidchik 2014). In addition, high cytoplasmic Na+ inhibited K+ uptake by the root AKT1 channel of Arabidopsis (Qi and Spalding 2004).

The main means by which plants can cope with excess Na+ are the salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway, comprising an array of diverse signaling intermediaries and regulatory proteins that ultimately control the activity of SOS1, the leading plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger governing the efflux of Na+ in roots and loading into the xylem vessels for the long-distance transport out of the roots. Counteracting the activity of SOS1 is the family of high-affinity K+ transport (HKT) proteins, which despite their name are Na+ transporters that operate in the retrieval of Na+ from the xylem sap in both monocots and dicots (Class I HKTs), and that constitute a high-affinity Na+ uptake pathway in the roots of monocots under K+ starvation (Class II; Horie et al. 2001, Sunarpi et al. 2005). There are excellent reviews dealing with these Na+ transport systems in glycophytes (Assaha et al. 2017), but much less is known in halophytes, a diverse group of plants highly tolerant to salinity (Flowers et al. 2010). In this review, we will summarize what is known about the SOS and HKT systems in halophytes and how the features of individual transporters may contribute to their salt tolerance. Emphasis will be given to comparative analyses between HKT1 orthologs from Arabidopsis and related halophytic species because structural and kinetic features of these proteins have been functionally related to salt tolerance.

The SOS pathway

In genetic terms, the most significant mechanism that plants use to overcome sodicity is the SOS pathway (Ji et al. 2013, Assaha et al. 2017). The molecular and physiological analyses of the SOS pathway have been conducted on glycophytic species in which forward and reverse genetic resources are available, whereas the knowledge gained from halophytes is still scant (Oh et al. 2010, Shabala 2013). The core SOS pathway was initially described as the combined roles of three proteins, SOS3, a calcium-binding protein, SOS2, a serine/threonine-protein kinase and SOS1, a Na+/H+ antiporter (Qiu et al. 2002, Quintero et al. 2002). SOS1 is activated by the combined functions of SOS2 and SOS3, which form a complex that directly phosphorylates and activates the Na+/H+ exchange activity of SOS1 (Quintero et al. 2011). Further research has incorporated additional elements and functions to the SOS pathway (Ji et al. 2013). CBL10/SCaBP8 is an alternative CBL subunit of SOS2/CIPK24 that regulates SOS1 activity mainly in shoots, whereas SOS3/CBL4 seems to be more important in the roots of Arabidopsis (Quan et al. 2007). CBL10 also appears to regulate SOS1 activity in association with CIPK8 (Yin et al. 2020). CBL10 and SOS2 also interact at the tonoplast, suggesting that the complex may alleviate Na+ toxicity by modulating the sequestration of Na+ in vacuoles through unknown transporters (Kim et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2019). Two 14-3-3 proteins bind to and inhibit SOS2 upon phosphorylation of Ser-294 by PKS5/CIPK11 (Zhou et al. 2014, Yang et al. 2019b). However, under salt stress, Ca2+-activated 14-3-3 proteins repress PKS5, thereby releasing the inhibition of SOS2 (Yang et al. 2019b). Moreover, when active, PKS5 down-regulates H+-ATPase activity at the plasma membrane (Fuglsang et al. 2007) and salt-dependent inactivation of PKS5 enhances the activity of H+-ATPase and Na+/H+ exchange (Yang et al. 2019b). Activation of MPK6, upon the salinity-induced synthesis of phosphatidic acid by phospholipase D (PLD), is also required for the full activity of SOS1 (Yu et al. 2010). The SOS pathway interacts with the regulation of carbon metabolism through the kinases GRIK1 and GRIK2 (a.k.a. SnRK1 activating kinases). GRIK kinases activate kinases SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 related to sugar metabolism, and also SOS2 under salt stress, thus, linking the regulation of cellular energy to salt tolerance (Barajas-Lopez et al. 2018). Last, salinity alters the time of flowering and, surprisingly, regulators of flowering have an impact on salt tolerance. For instance, GIGANTIA (GI), a positive regulator in the photoperiodic branch controlling flowering time, sequesters SOS2 under non-saline conditions. Upon salt stress and in a Ca2+-dependent manner, GI is degraded, flowering is delayed, and SOS2 released from inhibition, which then supports salt tolerance through SOS1 (Kim et al. 2013). Deletion of GI promotes superior salt tolerance by derepressing the SOS pathway. By contrast, SOS2 has no function in setting flowering time, but SOS3 plays a positive role in flowering specifically under salt stress by an as yet unknown mechanism (Li et al. 2007, Kim et al. 2013).

The SOS pathway serves two important processes leading to salt tolerance. One is a cellular-based mechanism that relies on the efflux of Na+ back to the apoplast or to the soil solution. The second but not least important function is the control of Na+ loading into the xylem, which has been confirmed in Arabidopsis, tomato and rice (Shi et al. 2002, Olias et al. 2009, El Mahi et al. 2019). The relative contribution of each of these two processes governed by the SOS proteins to the overall tolerance of the plant remains to be determined. It could be argued that the much dramatic salt-sensitive phenotype of the Arabidopsis mutants lacking the single-copy gene SOS1 compared to hkt1 mutants imply that Na+ efflux dominates over interorgan distribution. However, the function of SOS1 impinges in both processes, being the two of them defective in sos1 mutants.

In line with the fundamental roles of the SOS pathway in salt tolerance, RNAi-mediated knockdown lines of SOS1 in Eutrema salsuginea (previously known as Thellungiella salsuginea), an Arabidopsis related halophyte, lead to loss of halophytism, which further strengthens the importance of SOS1 as an ubiquitous halotolerance determinant (Oh et al. 2009). The superior salt tolerance of E. salsuginea could not be linked to a more efficacious SOS1 protein, but to the enhanced expression of SOS1 in both leaves and roots compared to Arabidopsis (Oh et al. 2009). Suppression of SOS1 rendered E. salsuginea with a high shoot Na+-accumulating phenotype, resulting from a lack of control over Na+ uptake and distribution via xylem. Na+ accumulated preferentially in the root xylem parenchyma of SOS1-suppressed plants, displacing K+ from these cells (Oh et al. 2009). The function of SOS1 in the regulation of xylem loading also appears to be crucial for the salt-accumulating halophyte Salicornia spp., in which the constitutively enhanced expression of SOS1 in the root could be essential to maintain a constant flow of Na+ via the xylem to the shoot (Yadav et al. 2012, Katschnig et al. 2015).

Despite the essentiality of the SOS pathway in every species in which its contribution to salt tolerance has been analyzed, SOS components have not been identified in quantitative genetics and genomic analyses of salt tolerance, with the only exceptions of SOS3/CBL4 in barley and wheat, and SOS1 of wheat (Rivandi et al. 2011, Luo et al. 2017). This implies that there is little natural variability in the SOS system between related species and cultivars with contrasting salt tolerance. This is further supported by the evolutionary constraints observed in SOS1/NHX7 compared to other members of the NHX family from 32 plant species (Pires et al. 2013). By contrast, HKT, which also play crucial roles in the Na+ and K+ homeostasis under salt stress, have been identified numerous times as QTLs and GWAS being significantly associated with either high K+ and/or low Na+ content in shoots, and with salt tolerance (Ren et al. 2005, Hamamoto et al. 2015, Nieves-Cordones et al. 2016, Henderson et al. 2018, Zhang et al. 2018, Cao et al. 2019). These findings, together with the salt-sensitive phenotype often associated to loss-of-function mutants, show that HKT proteins represent a paramount line of defense that plants use against high salinity, and that a significant natural variability exists that can be utilized in breeding programs (Munns et al. 2012, Hamamoto et al. 2015). Therefore, we will devote the rest of this review to update our current understanding of HKT protein structure and function.

Role of HKT transporters in salt tolerance

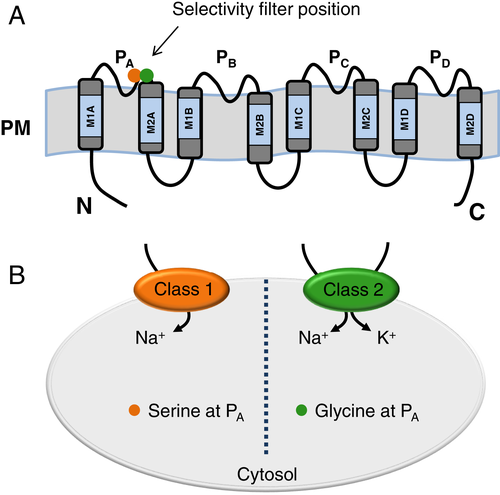

HKT transporters have been identified and widely characterized in model plants such as Arabidopsis and rice (Nieves-Cordones et al. 2016). HKT proteins are formed by four repetitions, MPM, M1A-PA-M2A–M1D-PD-M2D, where “M” corresponds to the transmembrane segment and “P” to pore-loop domain. The assembly of these repetitions forms a permeation pathway comparable to that of K+ channels. This structure was confirmed by the crystal structure of the K+ transporter TrkH from Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Cao et al. 2011). In three of the four pore-loop domains, PB to PD, all HKT proteins contain the GYG motif that is highly conserved in the selectivity filter of K+ transporting channels, but variability exists in the first position of this conserved motif in PA (Fig. 1). The HKTs family has been divided into two classes based on a structural determinant located in the first P domain, PA. Class I members, found both in monocots and dicots, have a highly conserved serine in PA and hence are also called the SGGG-type (Maser et al. 2002b, Hauser and Horie 2010). These are ubiquitous in plants, Na+-selective, and mostly promote the removal of Na+ from the xylem sap, which results in Na+ sequestration into xylem parenchyma cells (Maser et al. 2002a, Sunarpi et al. 2005). This mechanism prevents transport to, and accumulation of Na+ in the shoot over time and reduces Na+ toxicity by confining it to the roots, thus, protecting aboveground tissues from damage (Davenport et al. 2007). Numerous reports have shown that HKT1-type transporters determine the balance between Na+ and K+ under salt stress (Ren et al. 2005, Hauser and Horie 2010, James et al. 2011, Ali et al. 2012, Oomen et al. 2012, Maathuis 2014, Véry et al. 2014, Wang et al. 2014, Jaime-Pérez et al. 2017). In Class II members, found exclusively in monocots, the structural determinant of ion selectivity is composed of four glycine in the GYG motif of PA to PD (GGGG-type; Maser et al. 2002b, Hauser and Horie 2010). Although they are permeable to K+, HKT2s can operate as Na+/K+ symporters (Fig. 1; Horie et al. 2001, Platten et al. 2006). Through 3D comparative modeling, Cotsaftis et al. (2012) proposed that the replacement of G–S in Class I members imposed a steric hindrance causing K+ to be transported unfavorably. Likewise, in Class II HKTs, the G would facilitate the transport of K+, without ruling out that under certain conditions, the transport of Na+ was also possible (Maser et al. 2002b). Some exceptions to this rule are EcHKT1;2 from Eucalyptus camaldulensis, McHKT1;1 from Mesembryantemum crystallinum, EsHKT1;2 from Eutrema salsuginea (previously Thellungiella salsuginea or T. halophila) or EpHKT1;2 from Eutrema parvula (also known as Schrenkiella parvula; previously Thellungiella parvula). These proteins transport K+, but they contain a Ser in the PA domain (Fairbairn et al. 2000, Su et al. 2003, Jabnoune et al. 2009, Ali et al. 2012, Ali et al. 2018), which indicates that K+ permeability in HKTs depends on additional amino acids besides the Ser/Gly dichotomy in the pore. It is noteworthy that the HKT1 homologs departing from the S/G rule of ion selectivity are found mostly in either halophytes (e.g. EsHKT1;2 from E. salsuginea and McHKT1 from Mesenbryanthemum crystallinum) or salt-tolerant glycophytes (EcHKT1;2 from Eucalyptus camaldulensis; Assaha et al. 2017), suggesting an evolutionary advantage of this polymorphism in providing stress tolerance.

In the case of Class II members, two rice (Oryza sativa) HKT transporters, OsHKT2;1, isolated from Nipponbare and OsHKT2;2 present in the salt-tolerant Pokkali cultivar, have been amply characterized. These share high homology with 91% amino acid, and 93% cDNA sequence identity (Horie et al. 2001). However, in heterologous expression systems, they show differential Na+/K+ selectivity. OsHKT2;1 mainly transports Na+, whereas OsHKT2;2 mediates both K+ and Na+ uptake (Horie et al. 2001, Garciadeblas et al. 2003, Kader et al. 2006, Horie et al. 2007, Oomen et al. 2012). Unlike most members of Class II, OsHKT2;1 has a Ser residue instead of Gly in the PA domain. The Na+ uptake of OsHKT2;1 highly correlated with the presence of this residue (Horie et al. 2001, Maser et al. 2002a, Garciadeblas et al. 2003). Data obtained with the loss-of-function mutant oshkt2;1 suggest that OsHKT2;1 mediates a large Na+ influx into K+-starved roots, compensating the lack of K+ (Horie et al. 2007). OsHKT2;1 can also mediate K+ transport, depending on the external concentration of both K+ and Na+ (Jabnoune et al. 2009, Yao et al. 2010). On the other hand, OsHKT2;2 has the typical GGGG domain like the member of the Class II HKT transporters. It is highly permeable to both K+ and Na+ in a wide range of concentrations, and functions preferentially as a symporter (Horie et al. 2001, Yao et al. 2010). Studies have reported the impact that K+ ions exert on Na+ transport in OsHKT2;2. However, this effect has only been seen at low K+ concentrations, diminishing with higher concentrations of extracellular K+ (Oomen et al. 2012, Riedelsberger et al. 2018). Thus, at millimolar Na+ concentrations and in the absence of K+, OsHKT2;2 facilitates the entry of Na+ (Horie et al. 2001, Kader et al. 2006, Oomen et al. 2012), but with an increase in the concentration of K+, the uptake of Na+ ions is reduced (Riedelsberger et al. 2018). Another interesting case is the natural variant, NoOsHKT2;2/1, identified in the highly salt-tolerant rice cultivar NonaBokra (Oomen et al. 2012). This variant probably originated from a deletion in chromosome 6 producing a chimeric gene, where its 5′ region corresponding to the first three MPM domains, is homologous to OsHKT2;2, and more permeable to K+ (Horie et al. 2001). Its 3′ region corresponding to the last MPM domain is homologous with OsHKT2;1, weakly permeable to K+ and involved in root Na+ uptake (Horie et al. 2001, Golldack et al. 2002, Garciadeblas et al. 2003, Horie et al. 2007). NoOsHKT2;2/1 is essentially expressed in roots and shows a strong permeability for Na+ and K+, even at high external Na+ concentrations. Slopes of variation of NoOsHKT2;2/1 transport close to 20 mV per activity decade for both ions indicated that Na+ and K+ are the main ions transported, with a stoichiometry close to 1:1 (Jabnoune et al. 2009), contributing to salt tolerance in NonaBokra by enabling root K+ uptake under saline conditions (Oomen et al. 2012).

In wheat (Triticum aestivum), TaHKT2;1 seems to have a function similar to that of OsHKT2;1 (Horie et al. 2009). Preferentially expressed in the root cortex, this transporter has a role in root Na+ uptake induced by K+ deficiency, although it has also been reported to transport K+ (Schachtman and Schroeder 1994). In the same way, expression of HvHKT2;1 of barley (Hordeum vulgare) is induced by K+ deficiency in roots and shoots and by high Na+ concentration in shoots. In Xenopus oocytes, HvHKT2;1 has a low affinity for Na+, a variable affinity for K+ that depends on the external Na+ concentration, and inhibition by K+ at about 5 mM (Mian et al. 2011, Hmidi et al. 2019). Transgenic barley lines over-expressing HvHKT2;1 showed higher Na+ concentration in xylem, enhanced translocation of Na+ to shoots and higher Na+ accumulation in the leaves in comparison to the non-transformed plants. Moreover, transgenic plants that grew in limiting K+ conditions, showed a significant increase in shoot K+ content. This indicates that HvHKT2;1 could be involved in the absorption or re-absorption of K+ in the roots at very low concentrations of this cation (Mian et al. 2011). Recently, the transporter named HmHKT2;1 (Hordeum maritimum), homolog to HvHKT2;1, has been characterized (Hmidi et al. 2019). Electrophysiological analysis in Xenopus oocytes shows that HmHKT2;1 has a much higher affinity for both Na+ and K+ than HvHKT2;1 and a Na+/K+ symporter behavior in a very broad range of Na+ and K+ concentrations, due to reduced K+ blockage of the transport pathway. The analysis of chimeras between HvHKT2;1 and HmHKT2;1 allowed the identification of a region, composed of the fifth transmembrane segment, M1C and the adjacent extracellular loop, PC, as a key domain in the determination of the affinity for Na+ and the level of K+ in HKT2;1 (Hmidi et al. 2019).

Oddly, HvHKT1;5 from barley may negatively affect the plant performance in a saline environment because RNAi-mediated down-regulation of HvHKT1;5 resulted in salt tolerance instead of the anticipated sensitivity (Huang et al. 2020). HvHKT1;5 is a Na+-specific transporter inhibited by external K+ and localized to the plasma membrane of root stele cells. Contrary to common findings, knocking down HvHKT1;5 resulted in a decrease in the Na+ concentration in xylem sap and reduced Na+ translocation from roots to shoots, which would explain the increased salt tolerance of the transgenics compared with the wild-type plants. These findings suggest that HvHKT1;5 is involved in Na+ loading to the xylem, which is opposite to the function of the HKT1;5 homologs expressed in the root stele of rice and wheat (Ren et al. 2005, Munns et al. 2012). An unexplained observation is that expression of HvHKT1;5 increased under saline conditions (Huang et al. 2020), which could potentially result in greater salt sensitivity. The precise function of HvHKT1;5 in the salt-including behavior of barley remains to be determined.

Learning from halophytes

In the recent past, significant work has been carried out trying to understand the molecular mechanisms that plants use to cope with the saline condition. However, most of the work has been performed on glycophytic plants (salt-sensitive plants) such as Arabidopsis, rice, tomato and maize. Compared to glycophytes, halophytes (salt-resistant or salt-tolerant plants) could provide the best model system for studying successful adaptation to salt stress (Shabala 2013). Concentrations of NaCl over 100 mM severely inhibit the growth of most glycophytes. On the contrary, halophytes usually complete their life cycles in soils considered highly saline, of at least 200 mM NaCl or even reaching 400 mM in the case of euhalophytes (Flowers and Colmer 2008). Halophytes exploit the same three specialized mechanisms as glycophytes to maintain a balanced K+:Na+ ratio in their cytosol: distribution of Na+ to various tissues, the export of Na+, and salt sequestration in vacuoles, all of them governed through transporters (Flowers and Colmer 2008, Flowers et al. 2010, Oh et al. 2010, Kronzucker and Britto 2011, Shabala 2013). The salt-tolerance mechanisms in halophytes would be the same as those in glycophytes because they share common ancestry and evolution (Flowers et al. 2010). Evidence suggests that there are quantitative rather than qualitative differences between glycophytes and halophytes (Oh et al. 2010, Bartels and Dinakar 2013, Volkov 2015). This could occur due to an increased expression of genes related to the salt stress tolerance mechanism, or because halophyte proteins are more active than the corresponding glycophyte proteins, which indicate their better preparedness for harsh condition (Kumar et al. 2009, Das and Strasser 2013, Himabindu et al. 2016). The proteins belonging to HKT1-type transporters and SOS pathway are a clear example of these differences. The halophytes studied to date possess HKT1 and SOS1 proteins that predominantly contribute to their halophytic nature (Oh et al. 2009, Taji et al. 2010, Dassanayake et al. 2011, Ali et al. 2012, Wu et al. 2012, Ali et al. 2018, Wang et al. 2020). However, their expression patterns are different in salt-tolerant and sensitive varieties when subjected to NaCl stress. For instance, when the HKT1 expression among halophytic and glycophytic species of Cochlearia was compared, much higher expression levels were found in the halophytic species than in the glycophytic, supporting the idea that an increase in HKT expression is crucial to high-level salt tolerance (Nawaz et al. 2017). A comparison in the expression of genes in A. thaliana and Eutrema salsuginea, also revealed higher levels of HKT1 in E. salsuginea compared to A. thaliana (Wu et al. 2012). In the same way, EsHKT1;2 was strongly upregulated by salt stress while EsHKT1;1 expression was much lower. Another interesting case occurs with Salicornia dolichostachya, a highly tolerant and salt accumulating halophyte. Compared with its glycophyte relative Salicornia oleracea, S. dolichostachya shows constitutively high levels of SOS1 expression combined with suppression of HKT1;1 in roots, suggesting a halotolerance strategy that strongly favors Na+ loading into the xylem sap for delivery to aerial parts (Katschnig et al. 2015). However, the expression of other HKT1-like genes that might be present in S. dolichostachya was not explored.

As a close relative of Arabidopsis, E. salsuginea provides a model in which the halophytic nature of plants can be studied, drawing on the strengths of the glycophytic model and the exceptional ability to grow in seawater-strength concentrations of NaCl (Inan et al. 2004, Gong et al. 2005, Amtmann 2009, Ali et al. 2013, Bartels and Dinakar 2013). Moreover, the genomes for E. salsuginea and the related E. parvula are sequenced, which opens the door to new insights about the genetic basis of abiotic stress (Dassanayake et al. 2011, Wu et al. 2012). In this regard, these two Eutrema species are good model plants for studying salinity stress tolerance mechanisms (Vera-Estrella et al. 2005, Oh et al. 2009, 2010, Orsini et al. 2010, Volkov 2015).

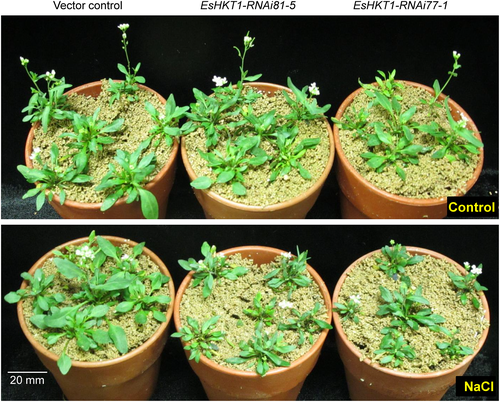

Previous studies indicate that salt tolerance in E. salsugineum does not arise due to complex morphological adaptations, but due to the robustness of the same mechanisms present in glycophytes (Bressan et al. 2001, Amtmann 2009). This adaptation can also occur through changes in gene regulation. Thus, E. salsugineum shows a higher level of expression in stress-related genes than its orthologs in A. thaliana, suggesting that the transcriptional network may be regulated for better performance (Taji et al. 2004, Wong et al. 2006, Taji et al. 2010). This adaptive modification would favor, at least partially, the tightly controlled net absorption of Na+ and the efficient and selective absorption of K+ compared to Arabidopsis (Volkov et al. 2004, Ali et al. 2012, Oh et al. 2014, Ali et al. 2018). We may thus expect that a gradation in salt tolerance may be determined by some genes and proteins that differ not by type but by responsiveness to stress (Oh et al. 2009,Ali et al. 2012, Ali et al. 2018). In addition, comparison of the genome sequences of E. salsuginea and E. parvula to that of Arabidopsis might highlight informative differences in the number of isoform for stress-related genes and their expressions such as SOS, HKT, and NHX (Oh et al. 2010, Ali et al. 2012, Wu et al. 2012, Oh et al. 2014, Ali et al. 2018). Recent studies reported the contribution of HKT1 isoforms to the halophytic character of E. salsuginea and E. parvula (Fig. 2; Ali et al. 2012, Ali et al. 2018), which we describe next.

HKTs and halophytism

The critical role of HKT1 in Na+ retrieval from the xylem under salt stress is well established in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Rus et al. 2001, Maser et al. 2002a, Sunarpi et al. 2005, Møller et al. 2009), and the crop plants tomato, rice and wheat (Ren et al. 2005, Munns et al. 2012, Almeida et al. 2014, Jaime-Pérez et al. 2017). Considering the importance of Class I (HKT1) proteins in salt-sensitive glycophytic plants, it is important to investigate their diversity and function in halophytic species. The E. salsuginea genome includes three HKT1 genes in a tandem array (Wu et al. 2012). These genes encode for three proteins, of which EsHKT1;1 and EsHKT1;3 are Na+ transporters, while EsHKT1;2, is a Na+/K+ co-transporter (Ali et al. 2012, Ali et al. 2016, Ali et al. 2018). Of the three homologs, only EsHKT1;2, is greatly induced following salt stress, highlighting its potential role in salt tolerance (Ali et al. 2012). By contrast, the EsHKT1;1 transcript, like AtHKT1, is less activated under salt stress, whereas EsHKT1;3 is expressed at low levels regardless of salt stress (Wu et al. 2012). Eutrema parvula, another Arabidopsis halophytic relative, contains two HKT1 genes, encoding the Na+ transporter EpHKT1;1, and the Na+/K+ co-transporter EpHKT1;2 (Dassanayake et al. 2011, Ali et al. 2018). Interestingly, EpHKT1;2, is upregulated upon salt stress, indicating again its likely contribution to the halophytic characteristics. On the other hand, upregulation of EpHKT1;1 is much lower than that of EpHKT1;2 (Ali et al. 2018). Finally, SsHKT1;1 from Suaeda salsa, a C3 halophyte, acts mainly as a K+ transporter and is involved in salt tolerance by maintaining cytosolic cation homeostasis, particularly K+ nutrition under salinity (Shao et al. 2014). These evidences indicate that homologs of HKT1-type transporters, play a critical role to regulate Na+ toxicity in halophytes and are therefore principal components of halophytism.

Arabidopsis contains a single copy HKT1 gene, encoding a Class I family member that shows a highly specific Na+ influx when expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Uozumi et al. 2000). Based on their protein sequences, homologs of HKT1 from E. salsuginea and E. parvula contain a serine residue in the selectivity filter position of the first pore-loop domain PA (SGGG-type) and therefore belong to Class I HKT1 transporters (Ali et al. 2012). However, isoforms from these halophytes, such as EsHK1;2 and EpHKT1;2, can take up both K+ and Na+, rather than only Na+, indicating that other important amino acids may control cation selectivity of these transporters apart from the S/G dichotomy in the selectivity filter (Ali et al. 2016). As we discussed earlier, HKT1 orthologs departing from the S/G rule in determining ion selectivity are found mostly in halophytes, suggesting an evolutionary advantage of this polymorphism in providing stress tolerance (Assaha et al. 2017).

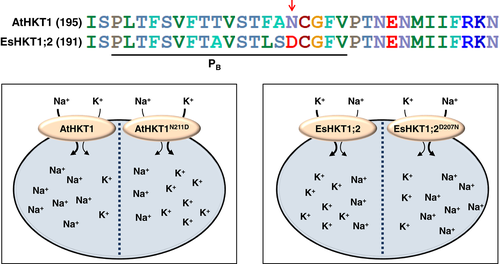

Alignment of amino acid sequences of three HKTs from E. salsuginea, two from E. parvula (now known as Schrenkiella parvula) and one from Arabidopsis (AtHKT1) with the well-known high-affinity K+ transporter of yeast, ScTRK1, provides clues about functional differences (Ali et al. 2012, 2016). Among them, EsHKT1;2 and EpHKT1;2 contain conserved aspartic acid residues (Asp207 and Asp205, respectively) in their second pore-loop region (PB) and also in the adjacent transmembrane domain, M2B (Asp238 and Asp236, respectively) (Ali et al. 2012). Interestingly, ScTRK1 possesses an Asp residue in the PB (Ali et al. 2012). By contrast, the rest of the HKT1 proteins published to date contain an asparagine residue (Asn) at these positions (Ali et al. 2016). Surprisingly, SIHKT1;1 from tomato, a Class I HKT1 transporter, contains a serine residue (Ser265) at this position (Asins et al. 2013). These findings suggested that the presence of Asp in the PA region of halophytic HKT1 transporters could be responsible for K+ selectively rather than Na+. Indeed, the substitution of Asp207 or Asp205 by Asn in EsHKT1;2 and EpHKT1;2, respectively, abolished K+ uptake, generating a canonical Class I Na+-selective transporter (Ali et al. 2016, 2018). In addition, plants expressing EsHKT1;2 or EpHKT1;2 in an athkt1 knockout background tolerate salt more effectively than those expressing AtHKT1. However, unlike EsHKT1;2, plants expressing EsHKT1;2D207N become sensitive to high salinity exactly like those expressing AtHKT1 (Ali and Yun 2016). Conversely, plants expressing AtHKT1N211D, where Asn211 is replaced by Asp211 show significant salt tolerance and gain the ability to take up K+ as well. Thus, by changing the asparagine residue in the PB region of AtHKT1 to aspartic acid, the transporter comes to resemble EsHKT1;2, with a high affinity for K+ transport resulting in salt tolerance (Ali et al. 2016; Fig. 3).

Recently, the mutagenesis of VisHKT1;1 (for Vitis interspecific) and TaHKT1;5-D from bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), established that charged amino acid residues located in the eighth transmembrane domain, M2D, converted these transporters into inward rectifiers of Na+ (Henderson et al. 2018). Thus, it seems clear that small changes in HKT proteins can improve salt tolerance. These results also suggest that through genome duplication and SNPs, halophytic HKTs gained the ability to take up K+ contributing to the halophytic nature of the species.

Conclusions and future perspectives

SOS1 and HKT1-like proteins are among the most important transporters that plants, glycophytes and halophytes alike, use to deal with high salinity. SOS1 exports Na+ out of the root and facilitates the loading into the xylem, thereby protecting the root from salt-induced damages. By contrast, HKT1-like proteins unload Na+ from xylem and help sequestering ions into xylem parenchyma cells to protect photosynthetic tissues. These two transporter systems function antagonistically in a refined way to spare the plant from Na+ toxicity, yet how their activities are co-regulated and fine-tuned to avoid a futile cycle of Na+ loading and unloading remains unknown.

Functional characterization of the SOS pathway and HKT1-type transporters in A. thaliana and E. salsuginea hint that these plant species use similar mechanisms to tolerate salinity. The question then is why is Arabidopsis salt-sensitive whereas its halophytic counterpart shows extreme tolerance toward salinity? Several factors could explain how E. salsuginea is different from Arabidopsis; for instance, the genes encoding the Na+/H+ antiporter (SOS1) and Na+/K+ transporter (HKT1) are more strongly induced in E. salsuginea compared to Arabidopsis (Oh et al. 2009, Wu et al. 2012), suggesting greater preparedness and responsiveness in the halophytic plant. Gene duplication of HKT1 homologs and neo-functionalization in E. salsuginea is another possible explanation (Dassanayake et al. 2011, Wu et al. 2012). These differences point to the co-evolution of the two ion transport systems playing a critical role in shaping the halophytic lifestyle of E. salsuginea. Furthermore, current knowledge suggests that halophytes possess highly developed and upgraded mechanisms that are presumably related to those present in glycophytes (Oh et al. 2014). Thus, the study of halophytic plants such as E. salsuginea and S. parvula that are close relatives to Arabidopsis may advance our knowledge of how plants achieve salt tolerance by using a similar repertoire of molecular resources. Combined with functional studies in Arabidopsis, analysis of homologous ion transporter, and their divergence in E. salsuginea may help us to understand how multiple ion transporters that contribute to ion tolerance have been acquired evolutionarily, permitting survival in environments with extreme levels of sodium ions. Gaining knowledge of the responses and strategies used by halophytes under saline conditions could allow their application to crop plants in the future.

Author contributions

All authors designed the work, collected information from literature and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Next Generation Bio-Green21 Program, Rural Development Administration (RDA), Republic of Korea (SSAC, PJ01318201 to DJY and PJ01318205 to JMP); the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (2019R1A2C2084096 to DJY) and Global Research Lab (2017K1A1A2013146 to DJY).

Open Research

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.