Rapid Weight Gain After Pediatric Kidney Transplant and Development of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Among Children Enrolled in the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies Cohort

On behalf of the NAPRTCS investigators listed in the appendix.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Given the risks of cardiovascular disease among pediatric kidney transplant recipients, we evaluated whether there was an association between rapid weight gain (RWG) following kidney transplantation and the development of obesity and hypertension among children enrolled in the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) registry.

Methods

This retrospective analysis of the NAPRTCS transplant cohort assessed for RWG in the first year post-transplant and evaluated for obesity and hypertension in children with and without RWG up to 5 years post-transplant. We evaluated three separate eras (1986–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2021). We performed chi-square and logistic regression analyses to assess cardiometabolic risk at three time points (1, 3, and 5 years post-transplant).

Results

The percent of children with RWG decreased across the three eras (1986–1999 37.3%, 2000–2009 23.0%, and 2010–2021 16.4%). Obesity was significantly more common among children with a history of RWG following transplant, with 48%–67% with RWG having obesity 5 years following transplant compared with 22%–25% without RWG. Hypertension was significantly more common in the RWG group than the non-RWG group at all but two time points. In logistic regression models, the odds of obesity in the RWG group compared with non-RWG was 2.55 (2.29–2.83), and the odds of hypertension were 1.00 (0.94–1.08). Steroid minimization protocols were associated with significantly less RWG.

Conclusions

RWG was significantly associated with obesity but not hypertension among pediatric kidney transplant recipients enrolled in NAPRTCS. Interventions targeting RWG following kidney transplant should be evaluated as a potential way to modify obesity rates following transplantation.

Abbreviations

-

- cIMT

-

- Carotid intimal media thickness

-

- CKD

-

- chronic kidney disease

-

- NAPRTCS

-

- North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies

-

- RWG

-

- rapid weight gain

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including kidney transplant recipients [1]. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors are therefore of particular interest in the pediatric CKD population.

Kidney transplantation can be associated with multiple metabolic changes, particularly in the first year following transplant when recipients often experience significant weight gain [2, 3]. Among adults, one study found an increase in truncal adiposity following transplant, without a concurrent increase in lean muscle mass despite increased physical activity levels [2]. Adults who developed obesity following kidney transplantation were at increased risk for hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease compared with transplant recipients who did not develop obesity [4]. There is also an association between the development of obesity following transplantation in adults and increased graft loss at 5 and 10 years following transplantation [4].

In the pediatric population, some research has shown that obesity at the time of kidney transplant is associated with poor graft outcomes and death [5, 6], though other studies have not shown increased risk of acute rejection despite increased likelihood of graft loss in obese pediatric kidney transplant recipients [7, 8]. There has been limited pediatric research evaluating metabolic consequences of rapid weight gain following pediatric transplantation.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors, specifically obesity and hypertension, in the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) transplant population, and to determine if there is an association between rapid weight gain in the first year after kidney transplantation and the development of cardiometabolic risk factors 1, 3, and 5 years after kidney transplantation. We also assessed secondary outcomes including transplant rejection, hospitalization, and mortality between the rapid weight gain and non-rapid weight gain groups, as well as associations between steroid-based protocols and dialysis prior to transplant with rapid weight gain.

2 Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study involving participants in the transplant arm of the NAPRTCS registry. We included all kidney transplant recipients between ages 2–18 years at the time of transplant who had at least 1 year of follow-up data. We excluded individuals who had graft loss within the first year of transplant, as these individuals would not have enough follow-up data to evaluate the outcomes of interest. We only analyzed data for a participant's first transplant and did not include data from subsequent transplants. We assessed data across three separate time periods based on enrollment date: patients enrolled before January 1, 2000 were part of the 1986–1999 era, those enrolled January 1, 2000–December 31, 2009 were part of the 2000–2009 era, and those enrolled after January 1, 2010 were part of the 2010–2021 era. This grouping was done to account for differences in immunosuppression practices over time, specifically the transition away from steroid-based immunosuppression regimens.

To assess for rapid weight gain, we calculated the sex-specific BMI for height-age at each time point. Height-age was the age at which the patient would be the median height for their current age; this method was used to account for the stunted growth often seen in pediatric patients with CKD and has been used in other studies evaluating the growth of children with CKD [9]. We calculated the percent difference in BMI from the median BMI for age (BMI%) at the time of transplant, and we then calculated the increase in BMI% over the first year. An increase in BMI% greater than 20 was considered ‘rapid weight gain’; these thresholds were based on previous studies of weight gain following kidney transplant in the NAPRTCS transplant population [9]. Baseline obesity prior to transplant was determined by the closest pre-transplant BMI available within the 6 months before transplant, and if these data were not available, then admission height and weight were used to calculate BMI.

We assessed cardiometabolic risk factors, specifically obesity and hypertension, at 1, 3, and 5 years following kidney transplantation. Obesity was defined as a BMI > 95%ile for height-age at each time point. Hypertension was defined as taking an antihypertensive medication or blood pressure > 95th percentile for age, sex, and height (based on 2017 AAP hypertension guidelines [10]). Hyperlipidemia and abnormal glucose metabolism could not be assessed, as there were insufficient longitudinal data for these parameters available in the registry.

Secondary outcomes of interest included whether there was a difference in rejection, hospitalization or death between the rapid weight gain and non-rapid weight gain groups. We also assessed whether individuals had received dialysis prior to transplantation and whether participants received steroid minimization protocols.

We performed t-tests to compare continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables. We performed a logistic regression analysis to assess for the risk of hypertension and obesity, controlling for rapid weight gain, age, gender, and time from transplant.

This study was approved under the institutional review boards of participating centers.

3 Results

The mean population age was 11 years and was similar across the RWG and non-RWG groups, although the RWG group consisted of fewer children in the 2–5 year age range and more children in the 6–12 year age range than the non-RWG group (Table 1a). There were more girls in the RWG group than the non-RWG group. Differences in race and ethnicity between the RWG and non-RWG groups were minimal. The most common etiologies for end-stage kidney disease included obstructive uropathy, congenital anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract (CAKUT), glomerulonephritis, and nephrotic syndrome. RWG was somewhat more common among the glomerular etiologies for ESKD, namely nephrotic syndrome and glomerulonephritis, while RWG was somewhat less common than non-RWG among those with a structural etiology for their kidney disease. Baseline BMI was similar in the RWG and non-RWG groups, and baseline obesity was more common in the non-RWG group compared with the RWG group (Table 1a). The proportion of participants on dialysis prior to transplant was similar in the RWG and non-RWG groups. Steroid-sparing regimens were more common in the non-RWG group than the RWG group. Use of steroid-sparing regimens increased over time (Table 1b).

| Characteristic | All (N = 6779) | Rapid weight gaina (N = 2096) | Non-rapid weight gain (N = 4683) | p (RWG vs. NRWG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (years) | ||||

| N | 6779 | 2096 | 4683 | < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.0 (4.7) | 11.6 (3.8) | 10.8 (5.0) | |

| Age categories (years), n (%) | ||||

| 2–5 | 1176 (17.4%) | 163 (7.8%) | 1013 (21.6%) | < 0.001 |

| 6–12 | 2530 (37.3%) | 988 (47.1%) | 1542 (32.9%) | |

| 13–18 | 3073 (45.3%) | 945 (45.1%) | 2128 (45.4%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 2777 (41.0%) | 995 (47.5%) | 1782 (38.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 4002 (59.0%) | 1101 (52.5%) | 2901 (62.0%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 3984 (58.8%) | 1189 (56.7%) | 2795 (59.7%) | 0.006 |

| Black | 1156 (17.1%) | 381 (18.2%) | 775 (16.6%) | |

| Hispanic | 1133 (16.7%) | 379 (18.1%) | 754 (16.1%) | |

| Asian | 13 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.3%) | |

| Other | 35 (0.5%) | 8 (0.4%) | 27 (0.6%) | |

| Not reported or unknown | 458 (6.8%) | 139 (6.6%) | 319 (6.8%) | |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Acute kidney injury | 191 (2.8%) | 40 (1.9%) | 151 (3.2%) | 0.002 |

| Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract | 1154 (17.0%) | 336 (16.0%) | 818 (17.5%) | 0.14 |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | 166 (2.5%) | 22 (1.1%) | 144 (3.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Glomerulonephritis (GN) | 983 (14.5%) | 360 (17.2%) | 623 (13.3%) | 0.002 |

| Hereditary ciliopathy | 251 (3.7%) | 85 (4.1%) | 166 (3.5%) | 0.3 |

| Hereditary GN | 161 (2.4%) | 59 (2.8%) | 102 (2.2%) | 0.11 |

| Hereditary tubulointerstitial nephritis | 387 (5.7%) | 97 (4.6%) | 290 (6.2%) | 0.01 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 883 (13.0%) | 297 (14.2%) | 586 (12.5%) | 0.06 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 1307 (19.3%) | 360 (17.2%) | 947 (20.2%) | 0.003 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 503 (7.4%) | 163 (7.8%) | 340 (7.3%) | 0.23 |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 176 (2.6%) | 40 (1.9%) | 136 (2.9%) | 0.02 |

| Traumatic/surgical | 52 (0.8%) | 13 (0.6%) | 39 (0.8%) | 0.35 |

| Not reported/Unknown | 565 (8.3%) | 224 (10.7%) | 341 (7.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Sex-specific BMI for-height-age | ||||

| N | 6779 | 2096 | 4683 | < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.1 (5.6) | 18.5 (4.2) | 19.4 (6.1) | |

| Sex-specific BMI for-height-age Z-score | ||||

| N | 6779 | 2096 | 4683 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.23 (8.27) | −0.28 (14.74) | 0.46 (1.27) | |

| Obesity pre-transplant, n (%)b | ||||

| N with pre-transplant height and weight data |

N = 2224 |

N = 659 |

N = 1565 |

|

| Yes | 317 (14.3%) | 83 (12.6%) | 234 (15.0%) | 0.14 |

| No | 1907 (85.8%) | 576 (87.4%) | 1331 (85.1%) | |

| On dialysis pre-transplant, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3680 (54.3%) | 1172 (55.9%) | 2508 (53.6%) | 0.09 |

| No | 3040 (44.8%) | 910 (43.4%) | 2130 (45.5%) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 59 (0.9%) | 14 (0.7%) | 45 (1.0%) | |

| Steroid sparing regimenc n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 943 (13.9%) | 170 (8.1%) | 773 (16.5%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 5836 (86.1%) | 1926 (91.9%) | 3910 (83.5%) | |

- a Rapid weight gain is defined by an increase in BMI% > 20 over the first-year post-transplant.

- b Obesity pre-transplant determined based on BMI for-height-age Z-score.

- c Steroid-sparing group is defined as the group of participants without the use of steroid medications 30 days after the transplantation (i.e., at baseline).

| Characteristic | Pre-2000 (n = 4119) | 2000–2009 (n = 1884) | 2010–2021 (n = 776) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (years), Mean (SD) | 10.86 (4.60) | 11.41 (4.65) | 10.78 (5.25) |

| Age categories (years) | |||

| 2–5 years | 704 (17.1%) | 293 (15.6%) | 179 (23.1%) |

| 6–12 years | 1629 (39.6%) | 662 (35.1%) | 239 (30.8%) |

| 13–18 years | 1786 (43.4%) | 929 (49.3%) | 358 (46.1%) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1669 (40.5%) | 772 (41.0%) | 336 (43.3%) |

| Race or Ethnicity | |||

| White | 2549 (61.9%) | 1027 (54.5%) | 408 (52.6%) |

| Black | 641 (15.6%) | 370 (19.6%) | 145 (18.7%) |

| Hispanic | 675 (16.4%) | 331 (17.6%) | 127 (16.4%) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.1%) | 11 (1.4%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.2%) | 32 (4.1%) |

| Not reported or unknown | 254 (6.2%) | 151 (8.0%) | 53 (6.8%) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||

| Acute kidney injury | 86 (2.1%) | 67 (3.6%) | 38 (4.9%) |

| Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract | 686 (16.7%) | 309 (16.4%) | 159 (20.5%) |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | 88 (2.1%) | 44 (2.3%) | 34 (4.4%) |

| Glomerulonephritis (GN) | 662 (16.1%) | 234 (12.4%) | 87 (11.2%) |

| Hereditary ciliopathy | 143 (3.5%) | 85 (4.5%) | 23 (3.0%) |

| Hereditary GN | 105 (2.6%) | 44 (2.3%) | 12 (1.6%) |

| Hereditary tubulointerstitial nephritis | 233 (5.7%) | 111 (5.9%) | 43 (5.5%) |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 510 (12.4%) | 263 (14.0%) | 110 (14.2%) |

| Obstructive uropathy | 827 (20.1%) | 336 (17.8%) | 144 (18.6%) |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 352 (8.6%) | 119 (6.3%) | 32 (4.1%) |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 104 (2.5%) | 50 (2.7%) | 22 (2.8%) |

| Traumatic/surgical | 31 (0.8%) | 12 (0.6%) | 9 (1.2%) |

| Not reported/unknown | 292 (7.1%) | 210 (11.2%) | 63 (8.1%) |

| Sex-specific BMI for-height-age, Mean (SD) | 18.5 (5.2) | 20.1 (6.4) | 20.1 (5.3) |

| Sex-specific BMI for-height-age Z-score Mean (SD) | 0.21 (1.49) | 0.15 (15.49) | 0.57 (1.84) |

| Obesity pre-transplanta | |||

| n with pre-transplant height and weight data | n = 1060 | n = 706 | n = 458 |

| Yes | 114 (10.8%) | 118 (16.7%) | 85 (18.6%) |

| On dialysis pre-transplant | |||

| Yes | 2245 (54.5%) | 989 (52.5%) | 446 (57.5%) |

| No | 1865 (45.3%) | 857 (45.5%) | 318 (41.0%) |

| Unknown/not reported | 9 (0.2%) | 38 (2.0%) | 12 (1.6%) |

| Steroid sparing regimen | 126 (3.1%) | 426 (22.6%) | 391 (50.4%) |

| Rapid weight gain | 1535 (37.3%) | 434 (23.0%) | 127 (16.4%) |

- a Obesity pre-transplant determined based on BMI for-height-age Z-score.

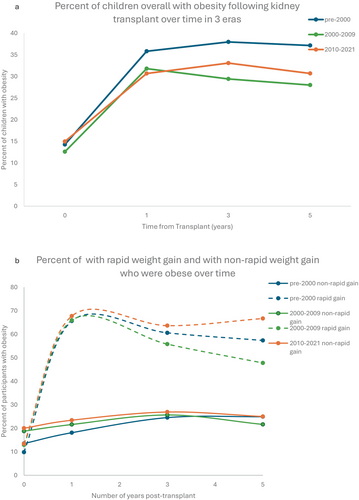

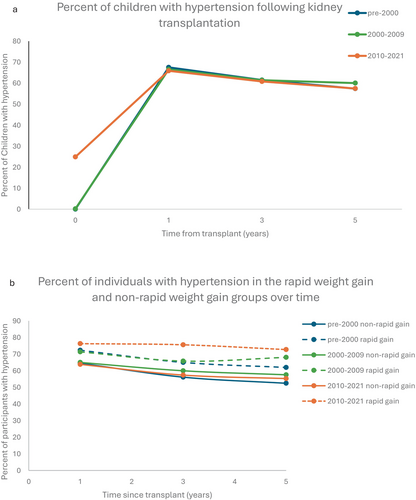

Baseline obesity (pre-transplant) occurred in 10.8% of patients pre-2000, and 16.7% and 18.6% of patients in the 2000–2009 and 2010–2021 eras, respectively (Table 1b). One-year post-transplant obesity ranged from 30.7%–35.8% (Figure 1a). Rates of baseline hypertension (pre-transplant) were difficult to determine due to missing registry data, but occurred in 57.4%–67.5% of patients following transplant and remained at sustained, high levels following transplantation (Figure 2a).

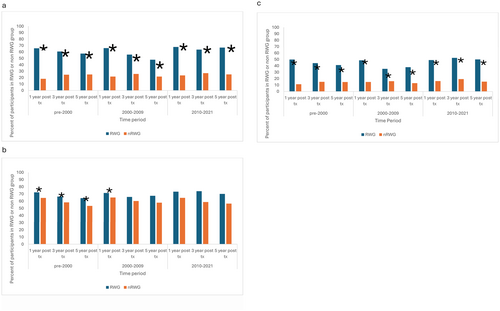

Rapid weight gain occurred in 37.3% of participants in the pre-2000 era, 23% of participants in the 2000–2009 era, and 16.4% of participants in the 2010–2021 era (Table 1b). Obesity was significantly more common in the rapid weight gain group than in the non-rapid weight gain group at each time point across each era following transplant (Figure 3, Appendix S1). Baseline obesity was significantly more common in the group that did not develop rapid weight gain compared with the rapid weight gain group (Figure 1b). In unadjusted analyses, hypertension was significantly more common in the RWG group at all timepoints in the pre-2000 era and was non-significantly higher at the remaining time points (Figure 3, Appendix S1). One year post-transplant, close to 50% of participants in each era who were in the rapid weight gain group had two cardiometabolic risk factors (hypertension and obesity) compared with 11%–16% in the non-rapid weight gain group (Appendix S1). Both obesity and hypertension persisted at relatively constant levels in the rapid weight gain group and the non-rapid weight gain group for up to 5 years following kidney transplantation (Figures 1b, 2b). In the most current era, 50% of participants in the rapid weight gain group had hypertension and obesity compared with 15.3% in the non-rapid weight gain group 5 years post-transplant (Appendix S1).

When controlling for age, race, sex, and time from transplant, logistic regression analysis showed significantly higher odds of obesity (OR 2.55, 95% CI 2.29, 2.83) but not hypertension (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94, 1.08) in the rapid weight gain group compared with the non-rapid weight gain group (Table 2,3).

| Variable | Odds ratio estimate | 95% confidence interval | Chi square statistics | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | 2.55 | (2.2916, 2.8312) | 300.38 | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.00 | (0.9360, 1.0758) | 0.01 | 0.9232 |

- Note: Obesity and hypertension over time at: 30 days (baseline), 1, 3, and 5 years post-transplant. N Obesity: 5194 subjects. N Hypertension: 4998 subjects.

| Characteristic | Pre-2000 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid weight gain (n = 1535) | Non-rapid weight gain (n = 2584) | p | Rapid weight gain (n = 434) | Non-rapid weight gain (n = 1450) | p | Rapid weight gain (n = 127) | Non-rapid weight gain (n = 649) | p | |

| On dialysis pre-transplant | 842 (54.9%) | 1403 (54.3%) | 0.17 | 254 (58.5%) | 735 (50.7%) | 0.01 | 76 (59.8%) | 370 (57.0%) | 0.83 |

| Steroid minimization | 51 (3.3%) | 75 (2.9%) | 0.45 | 70 (16.1%) | 356 (24.6%) | 0.001 | 49 (38.6%) | 342 (52.7%) | 0.004 |

| History of hospitalizationa | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 0.27 | 3 (0.7%) | 25 (1.7%) | 0.12 |

45 (35.4%) |

276 (42.5%) | 0.14 |

| Deceased | 47 (3.1%) | 65 (2.5%) | 0.30 | 4 (0.9%) | 4 (0.3%) | 0.07 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.2 |

| History of any rejectionb | 988 (64.4%) | 1486 (57.5%) | < 0.001 | 148 (34.1%) | 391 (27.0%) | 0.004 | 39 (30.7%) | 182 (28.0%) | 0.54 |

| Rejection in first year following transplant | 770 (50.2%) | 1139 (44.1%) | < 0.01 | 76 (17.5%) | 226 (15.5%) | 0.34 | 23 (18.1%) | 83 (12.8%) | 0.11 |

| Rejection after first year following transplant | 218 (14.2%) | 347 (13.4%) | 0.48 | 72 (16.6%) | 165 (11.4%) | 0.004 | 16 (12.6%) | 99 (15.2%) | 0.44 |

- a For patients with multiple hospitalization forms submitted, only the first instance of hospitalization was used.

- b For participants who multiple several acute rejection forms submitted, only the first instance of rejection was used.

Over half of participants were on dialysis prior to undergoing kidney transplantation, and pre-transplant dialysis was more common in the rapid weight gain group, but was significantly so in only one era. In the most recent two eras, rapid weight gain was significantly lower in participants who had received steroid minimization protocols compared with participants who received steroids. The number of individuals on steroid minimization protocols prior to 2000 was very low (Table 3).

Overall allograft rejection was significantly more common in the RWG group compared with the non-RWG group in the first two eras, though early versus late rejection did not vary significantly between RWG and non-RWG groups. There was no significant difference in hospitalizations or deaths across the RWG and non-RWG groups (Table 3).

Among those participants within the RWG group who developed obesity, male sex was the only factor significantly associated with RWG (Table 4).

| RWG with obesity (n = 224) | RWG without obesity (n = 1872) | Non RWG with obesity (n = 751) | Non RWG without obesity (n = 3932) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (years) | ||||

| N | 224 | 1872 | 751 | 3932 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.75 (3.82) | 11.55 (3.83) | 10.12 (5.33) | 10.87 (4.95) |

| Age categories at transplant (years), n (%) | ||||

| 2–5 years | 17 (7.6%) | 146 (7.8%) | 217 (28.9%) | 796 (20.2%) |

| 6–12 years | 101 (45.1%) | 887 (47.4%) | 220 (29.3%) | 1322 (33.6%) |

| 13–18 years | 106 (47.3%) | 839 (44.8%) | 314 (41.8%) | 1814 (46.1%) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 79 (35.3%) | 916 (48.9%) | 295 (39.3%) | 1487 (37.8%) |

| Male | 145 (64.7%) | 956 (51.1%) | 456 (60.7%) | 2445 (62.2%) |

| Hypertension at transplant (day 30), n (%) | (n = 220) | (n = 1822) | (n = 712) | (n = 3769) |

| Yes | 4 (1.8%) | 20 (1.1%) | 45 (6.3%) | 139 (3.7%) |

| No | 216 (98.2%) | 1802 (98.9%) | 667 (93.7%) | 3630 (96.3%) |

| Steroid sparing regimen (day 30), n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 20 (8.9%) | 150 (8.0%) | 145 (19.3%) | 628 (16.0%) |

| No | 204 (91.1%) | 1722 (92.0%) | 606 (80.7%) | 3304 (84.0%) |

4 Discussion

Kidney transplantation is associated with multiple long-term cardio-metabolic effects, and cardiovascular disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the pediatric kidney transplant population [1]. Carotid intimal media thickness (cIMT), which is an early marker of cardiovascular disease, is greater among pediatric solid organ transplant recipients than healthy children, and myocardial strain is also higher among pediatric kidney transplant recipients with obesity or metabolic syndrome [11]. One study found an increase in metabolic syndrome in pediatric kidney transplant recipients from 18.8% at the time of transplant to 37.0% one-year following transplant, with significant increases in hyperglycemia, obesity, and hypertension over this time period as well [3].

While kidney transplantation is associated with increased risk of cardiometabolic disease, the contribution of rapid weight gain following transplantation to this risk is less clear. Rapid weight gain over a relatively short period of time has been associated with multiple long-term health consequences in children with a history of prematurity [12], including increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease in adulthood [13] and increased cIMT [14]. In older children, rapid weight gain among children taking risperidone was associated with the development of metabolic syndrome [15]. Rapid weight gain has previously been demonstrated in the first year following transplantation in children receiving kidney transplants [9, 16], but the longer-term metabolic consequences of this rapid weight gain have not been well delineated.

We found that obesity was more common among children in NAPRTCS who experienced rapid weight gain following transplantation than in children who did not experience rapid weight gain. Obesity also persisted 5 years post-transplant in these children with initial RWG. Hypertension was non-significantly higher at most time points among those with RWG. Hypertension was very common among all transplant recipients, affecting 50%–70% of transplant recipients. Almost half of participants with RWG had two cardio-metabolic risk factors, obesity and hypertension. Given the potential cumulative effects of multiple risk factors on cardiovascular health [17], this accumulation of cardiometabolic risk factors in children with RWG may have implications for long-term health outcomes, especially given the data in our study showing persistence of these metabolic changes 5 years post-transplant.

Metabolic changes are a known complication of adult kidney transplantation [18], and the patterns manifested by the children in the NAPRTCS registry mirror patterns seen in adult populations, where weight gain was notable even 3 months post transplant [2]. Given the younger age and longer life expectancy of pediatric patients, however, the cumulative impacts of these metabolic changes immediately following transplant have the potential for even more profound long-term cardiovascular consequences than in adults. This study is one of the first to assess this combination of cardiometabolic risk factors, namely hypertension and obesity, over many years following kidney transplantation in children.

The relatively fixed rates of hypertension and obesity during long-term follow-up following transplantation point towards the difficulty clinicians face in reversing these metabolic changes once established. Studies have similarly shown that individuals who have significant weight gain post-transplant are more likely to have a persistently elevated BMI [16, 19, 20].

While the cause of rapid weight gain is likely multifactorial, rates of rapid weight gain decreased over time, and rapid weight gain was less common among children who were on steroid minimization protocols (Table 4). Given the known effects of steroids on weight, the decline in rapid weight gain over time may have been related to steroid exposure.

Similarly, hypertension remained at high levels over time across all 3 eras, without substantial changes across this time span. This picture is clouded, however, by the rise in obesity in the general pediatric population across the US during this time period, with obesity rates increasing from 5% in 1978 to 18.5% in 2016 [21]. It is possible that the impact of a decline in rapid weight gain was countered by the overall obesity trends in the pediatric population over the course of this study. In our study, baseline obesity rates increased across the three eras, which may partially account for the lack of overall decline in obesity in kidney transplant recipients.

Factors associated with rapid weight gain included older age, female sex, and a pre-transplant diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. Understanding potential risk factors for rapid weight gain could be helpful in targeting pre-transplant counseling surrounding nutrition and potential weight change patterns following transplantation.

Given the associations between rapid weight gain and obesity, as well as known complications of obesity in individuals with kidney transplant [3, 11], interventions directed at rapid weight gain could potentially lead to improved outcomes. In adults, small studies have shown that individuals who are more physically active and consume fewer high-calorie beverages have less weight gain following kidney transplant [22]; similar studies in children are not available and caution should be taken applying adult nutritional guidance to pediatric patients, who are still growing. This does remain an area, however, where further investigation may be warranted. Our data would suggest that targeting interventions at older pediatric patients may be most helpful. Specific studies of nutritional intake and activity in children post-transplant would be helpful but are not available in the NAPRTCS dataset. Given the need for pediatric patients to transition to adult care, it may also be important to include information about RWG for adult providers to ensure close monitoring for the development of other cardiometabolic risk factors as patients age.

Interestingly, RWG was more common among female participants; however, a larger percentage of male patients with RWG developed obesity than female patients with RWG (Table 4). Obesity was more common in male patients overall, paralleling trends in the US over the past decade [23]. Some individuals with RWG may have been underweight pre-transplant and thus the rapid-weight gain post-transplant allows them to reach a more “healthy” body weight. It may therefore be reasonable to consider additional counseling for patients who are under-weight prior to transplant about the changes in appetite that may occur post-transplant. RWG was seen more commonly in the older age groups, and it is therefore possible that pubertal hormones may have played a role in the rapid weight gain noted, particularly as this is an age when children normal experience significant changes in body composition.

Rapid weight gain was significantly associated with allograft rejection at only some points, and was not as significantly associated with hospitalization or death in our study population. Prior findings looking at obesity and graft survival have been mixed, with both significant and non-significant associations reported [5, 8, 24]. In our study, there was not a significant difference in the association between RWG and early (1 year post-transplant) versus late rejection.

This study did have a few limitations. While blood pressure measurement, antihypertensive use, and BMI were measured consistently throughout the duration of the cohort in transplant recipients, other cardiometabolic risk measures including lipid profiles and markers of glucose metabolism are more recent additions to the NAPRTCS data collection tool, and therefore were not able to be reliably used in this longitudinal analysis. Given general trends in obesity, some of the changes seen over time could represent this overall increasing predisposition to childhood obesity and not be specifically associated with kidney transplantation. In addition, while height and weight are generally checked at all transplant follow-up visits, NAPRTCS collects data every 6 months, and therefore closer assessment of changes in weight and BMI was not possible.

We found that rapid weight gain in the first year post transplantation was associated with sustained cardiometabolic changes up to 5 years post transplantation. Steroid minimization protocols were associated with significantly less RWG, and therefore continued efforts to minimize steroid use post-transplantation as able could impact post-transplant RWG and potentially obesity and other metabolic complications or transplants. Interventions targeted specifically towards reducing rapid weight gain in the first year following transplantation may therefore be a way to temper some of the metabolic complications of pediatric kidney transplantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the NAPRTCS participants and all of the NAPRTCS centers for making this research possible. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Jing Zhang, PhD, for her initial assistance with data analysis.

We did not receive external funding for the publication of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.