Kidney adolescent and young adult clinic: A transition model in Africa

Abstract

Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have challenges unique to this developmental period, with increased rates of high-risk behavior and non-adherence to therapy which may impact the progression of kidney disease and their requirement for kidney replacement therapy (KRT). Successful transition of AYA patients are particularly important in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where KRT is limited, rationed or not available. Kidney AYA transition clinics have the potential to improve clinical outcomes but there is a paucity of data on the clinical translational impact of these clinics in Africa. This review is a reflection of the 20-year growth and development of the first South African kidney AYA transition clinic. We describe a model of care for patients with CKD, irrespective of etiology, aged 10–25 years, transitioning from pediatric to adult nephrology services. This unique service was established in 2002 and re-designed in 2015. This multidisciplinary integrated transition model has improved patient outcomes, created peer support groups and formed a training platform for future pediatric and adult nephrologists. In addition, an Adolescent Centre of Excellence has been created to compliment the kidney AYA transition model of care. The development of this transition pathway challenges and solutions are explored in this article. This is the first kidney AYA transition clinic in Africa. The scope of this service has expanded over the last two decades. With limited resources in LMICs, such as KRT, the structured transition of AYAs with kidney disease is not only possible but essential. It is imperative to preserve residual kidney function, maximize the kidney allograft lifespan and improve adherence, to enable young individuals an opportunity to lead productive lives.

Abbreviations

-

- AYAs

-

- Adolescents and young adults

-

- CAKUT

-

- Congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract

-

- CKD

-

- Chronic kidney disease

-

- ESKD

-

- End-stage kidney disease

-

- GSH

-

- Groote Schuur Hospital

-

- GSH-ACE

-

- Groote Schuur Hospital Adolescent Centre of Excellence

-

- IPNA

-

- International Pediatric Nephrology Association

-

- ISN

-

- International Society of Nephrology

-

- KRT

-

- Kidney replacement therapy

-

- LMIC

-

- low- and middle-income countries

-

- RCWMCH

-

- Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital

-

- SA

-

- South Africa

-

- UK

-

- United Kingdom

-

- UK OKAC

-

- United Kingdom Oxford Young Adult Clinic

1 INTRODUCTION

Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have challenges unique to this developmental period requiring tailored management. Adolescence is defined as a phase of life between the age of 10 and 19 years,1 and young adults are defined as individuals between the age of 15 and 25 years.2 Transition of AYAs between the pediatric and adult nephrology services is of critical importance. Failure to prepare AYAs for transition can lead to poor clinic attendance, increased non-adherence,3 progression of kidney disease and even kidney allograft loss.4, 5 In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), these challenges are amplified by poverty, resource limitations and priority policies. In South Africa (SA), progression of kidney disease has severe consequences and can result in mortality6, 7 as kidney replacement therapy (KRT) is rationed in the SA government sector due to priority setting as a consequence of resource constraints. Thus, the establishment of kidney AYA transition clinics are of critical importance.

2 IMPORTANCE OF ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT TRANSITION CLINICS

There is a growing body of evidence describing effective models of the transition of adolescents with chronic conditions, with improved outcomes.2, 8 Advances in medical treatment have led to improved pediatric survival rates with more patients reaching young adulthood.9 The process of transitioning encompasses a purposeful, planned movement of adolescents with chronic illnesses from pediatric to adult care.10 It cannot be attributed to a singular event but is a coordinated process ensuring continuity of care.10

Adolescents undergo rapid physical, cognitive and psychosocial development. Brain development is estimated to be completed in most individuals by the age of 25 years.9 AYAs have increased rates of high-risk behavior, including non-adherence.11 In the setting of CKD, there may be the additional challenge of cognitive impairment, which is often found in advanced kidney disease.6, 7 These factors add to the complexity of the transition process from the familiar fully supervised “parent driven” pediatric setting; to a new adult service where autonomy and “patient-driven” care is expected.12 AYAs tend to experience adult nephrology clinics as busier, having higher patient to clinician ratios, shorter medical consultations, older patient populations and the expectation to assume full responsibility for their health and well-being.13 Transition clinics provide a structured approach to empower AYAs to make this adjustment efficiently. These adolescent-friendly clinics can address health care needs, and in addition, focus on high-risk adolescent behavior. They also aid in navigating the new adult health care service.

Despite the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the International Pediatric Nephrology Association's (IPNAs) consensus statement on the ideal parameters for adolescent transition,14 globally there is a lack of uniform practice in transitioning adolescents with kidney disease.15-19 Table 1 reflects a global comparison on patient experiences in nephrology transition clinics. Common themes identified include anxiety in leaving a familiar setting, lack of preparedness for transfer and difficulty adjusting to autonomy required in adult care.20-24 Patient-centered measurements have demonstrated the effectiveness of AYA transition clinics with improved self-management, optimism, emotional resilience, satisfaction, and engagement with healthcare services.25, 26 Medical outcomes also improved with good transition practices.27 Globally, well transitioned kidney transplant recipients have demonstrated improved adherence, fewer episodes of rejection, and less graft failure.28, 29

| Country | USA20 | UK21 | Australia22 | Germany23 | South Africa24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 2011 | 2014 | 2009 | 2013 | 2022 |

| Research design | Quantitative: questionnaire | Quantitative: cross-sectional questionnaire | Quantitative: retrospective chart review & questionnaire | Quantitative: 3 different transition models were compared via questionnaire | Qualitative; phenomenological analysis with in-depth interviews |

| Sample population | 21 KT patients

|

90 CKD stage 4 and 5 patients. Including advanced CKD, dialysis, transplant | 11 KT | 59 KT | 6 post-transplant

|

| Age (years) | Mean pre-transition age 20.6, post-transition age 21.6 | Age 15–25 | Mean age 19.5 | Greater than age 18 | Age 18–22 |

| Transition clinic | Dedicated transition clinic, based at a hospital, with a pediatric and adult nephrologist | ||||

| Assessment transition stage | Pre- and post-transition | Not described | Post-transition | Pre- and post-transition | Post-transition |

| Key findings |

|

|

|

<50% felt prepared for transfer to adult care |

|

- Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; KT, Kidney Transplant; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

In SA, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and the requirement of KRT is a significant public health care challenge.30 A minority of the SA population (16%) have access to private health insurance, which provides full access to KRT.31 In contrast, the majority of the SA population (84%) are supported by the government healthcare system, which has significant resource restrictions, including rationing of KRT for both adolescents and adults.31, 32 Future kidney transplantability is often the overarching principle for KRT access eligibility. Adherence is essential to be considered as a good kidney transplant candidate. Non-adherence is very common and complex to manage among AYAs. Poor adherence is often expressed in the delay or omission of medication doses, sub-therapeutic drug levels, poor appointment attendance, as well as difficulty following through with medical advice.27 In SA, AYAs who are non-adherent are in a precarious position as they could be declined eligibility to adult KRT programs. In this setting, an unsuccessful transition with a non-adherent adolescent could be a death sentence. This is vastly different to high-income settings, where a poor transition with kidney allograft failure in AYAs translate to recommencement of chronic dialysis and being evaluated for future kidney transplant re-listing.33 Therefore, in AYAs with CKD, it is imperative to preserve residual kidney function, monitor adherance to medical therapy, and maximize the success of transplantation to enable young individuals to have successful outcomes.28

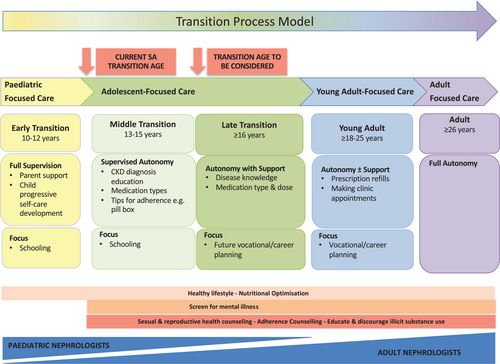

Historically, the SA government has demarcated the health allocation budget for pediatric services to patients younger than 13 years of age and funding toward adult services for patients older than 13 years of age. In isolated exceptional cases, where patients are highly complex and less mature with emotional and developmental delay, motivations are done to retain these patients at the pediatric service until the age of 18 years. Thus, in the majority of cases, transition occurs as early as 13 years. This practice is similar across most pediatric facilities in SA, as well as many African countries.34, 35 Thirteen is a very young age for patients to transition and engage with adult health care services.35 The SA transition age contrasts to international centres where the transition age is higher, reported to be between 18–21 years of age.13, 33, 36-38 The early age of transition directly impacts the management of AYAs, and patients with complex kidney diseases require an understanding of the nuances related to the age of transition.

There is a paucity of data on kidney transition clinics in LMICs. This could be attributed to lower gross national income, lower expenditure on health, lack of resources, lack of registry data as well as lower numbers per country of nephrologists.39

This paper describes the structure of the first dedicated kidney AYA transition clinic in SA. It illustrates a transition model of care and highlights the need for specialized kidney services for AYAs transitioning from pediatric to adult services. Furthermore, it explores challenges and solutions.9

3 BACKGROUND AND DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSITION MODEL

Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital (RCWMCH) and Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) are internationally renowned academic tertiary health care centers located in SA. GSH is one of the main adult referral centers for RCWMCH adolescent nephrology patients.

In 2002, five patients with advanced CKD or post-kidney transplant, transitioned from pediatric to adult health care centres with tragic outcomes. The transfer between the two centers took place in the form of a letter given to the patient to take to the referral center. At the time, there was no advocacy or dedicated medical or support staff for transitioning adolescents to the adult hospital. After the transfer, all five patients disengaged from medical therapy with poor adherence to treatment leading to either ESKD or kidney allograft failure. Due to recurrent non-adherence, all patients were declined acceptance to the adult government-sector KRT program. This was a devastating outcome for both pediatric and adult nephrologists. This event sparked an initiative to develop a new approach to transition adolescents. In 2002, a new transition care pathway for adolescents with ESKD was established. This occurred in an era where transition clinics were globally not well established. The initial kidney transition clinic focused on post-kidney transplant recipients, aged 13–18 years, and were located at the adult tertiary hospital. Due to staffing constraints and lack of training in adolescent nephrology, the scope of this clinic was limited. A dedicated pediatric nephrologist attended this clinic supported by availability of adult nephrologists. Adolescents had access to a clinical psychologist and social worker at clinic visits. There is no data available regarding the outcomes of this clinic.

3.1 The power of international collaboration and outreach

The United Kingdom Oxford Young Adult Clinic (UK OYAC) has been instrumental in support, outreach and collaboration with the SA kidney AYA clinic. In addition, the SA kidney AYA clinic has been the beneficiary of fundraising initiatives organized by UK OYAC, including funding from the annual United Kingdom (UK) post-kidney transplant Cape Town Argus Cycle Tour group.

3.2 Kidney AYA clinic re-designed

In 2015, the kidney AYA clinic was re-designed to form an integrated model, which aimed to form a bridge between pediatric and adult nephrology services. An innovation grant was awarded to design a “youth-friendly” kidney clinic.40 The first step in this process involved a needs assessment of AYAs with kidney disease attending the adult service. A qualitative questionnaire was designed and assessed patient experiences of the current service. Six themes were identified, including: (1) feeling of isolation, (2) anxiety, (3) dissatisfaction of physical appearance, (4) difficulties in communicating with staff, (5) staff not appreciating challenges related to lifestyle changes, and (6) difficulties in adherence to chronic medication. The second step in the process, included a series of three workshops that focused on designing a kidney AYA service that addressed those six themes. This involved the multidisciplinary nephrology staff, AYAs with kidney disease and their respective families. Four key points arose from these workshops. Firstly, AYAs wished to be in a clinic together, irrespective of their age where adolescents could be supported by older peers and older peers could mentor younger adolescents. Secondly, AYAs wished to be in the same clinic, irrespective of cause or severity of kidney disease, that is, CKD, dialysis and kidney transplant recipients to reduce the fear of future progression. Thirdly, patients wished to get to know one another, to decrease feelings of loneliness and isolation. Lastly, patients wished to have a service that was approachable and easier to access with school, university or work commitments. This formed the foundation of the re-designed kidney AYA clinic.

4 CURRENT TRANSITION MODEL

Key features of the new transitional care model included, (1) pre-transition discussions at age 10–12, (2) the transition process starting at the pediatric center (with adult nephrologists joining pediatric clinics), and continuing care at the adult center (with pediatric nephrologists joining the adult clinic), (3) expanding the adult center transition age to include patients up until the age of 25 years, (4) inclusion of all patients with kidney disease irrespective of severity, including KRT, (5) an afternoon clinic to accommodate for school and work commitments early in the day, and (6) having a dedicated multidisciplinary team with inter-departmental collaboration.

4.1 Structure of pediatric clinic

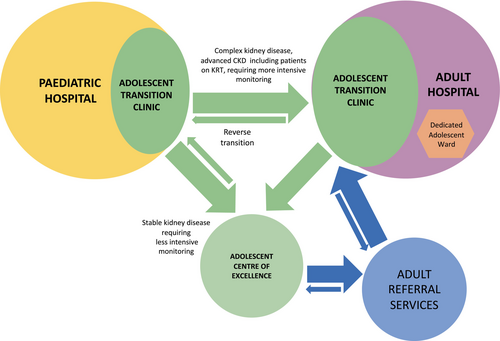

The transition pathway starts at the pediatric center, RCWMCH, and includes patients with CKD and those on KRT, ranging from 10 to 18 years of age. An adult nephrologist joins the pediatric clinic in assessing adolescent patients monthly. At this stage, the topic of future transition is introduced, as early as 10–12 years of age, and the future transfer is discussed over numerous visits. There is full supervision by the parents and clinician, with a gradual increase of patient self-care. As patients develop a more engaging and independent role, older patients are seen individually, away from their parents for short periods during the clinic visit and assessed for transition readiness. The clinic is supported by a dedicated dietician, social worker and transplant coordinator for kidney transplant patients. Patients who have complicated kidney disease or have received a kidney transplant are transferred to the GSH kidney AYA clinic. Patients with stable, less complicated kidney disease are referred to the GSH-Adolescent Centre of Excellence (GSH-ACE), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Support from medical managers at both pediatric and adult services has been of paramount importance. It is important for transition pathways to be structured, strengthened, and streamlined. It is essential to understand that transition can be dynamic and requires the transfer of adolescents to be tailored to the individual. This is illustrated in pediatric post-kidney transplant cases, where the transition age is often extended, for example, 16 years. Another case example includes unexpected teenage pregnancies, where patients require transition to adult services earlier for comprehensive co-management with obstetric and neonatology teams. Transition can be bidirectional, as seen in adult services with index presentation cases of 13-year-olds, who are physically small or emotionally immature, requiring KRT. In these cases, patients are discussed for temporary transfer to the pediatric service (reverse transition), on a case-by-case basis, and thereafter transitioned back to the adult service. This is a challenging space to navigate with strict budget allocation and resource restrictions.

4.2 Role of GSH-ACE

The GSH-ACE service was launched in July 2021 in response to the growing need for tailor-made adolescent services. This is a government-funded initiative and fully supported by medical managers at the adult service. GSH-ACE provides dedicated adolescent health care with specialized clinics for patients aged 13–18 years, for a vast range of chronic conditions. This unit is run by a dedicated adolescent pediatrician. The aim of this center is to ease the transition from pediatric to adult care. The concept of having a “familiar face in a new setting” is used to reduce stress and anxiety during transition. This center has access to specialized clinics with extensive counselling services, including genetics, psychiatry, sexual and reproductive health, and transgender support. GSH-ACE forms an important link between the pediatric and adult service.

The GSH-ACE kidney clinic occurs monthly, managed by the adolescent pediatrician and pediatric nephrologist. This clinic is aimed at stable, less complicated kidney disease. It also caters for young patients with hypertension associated with the metabolic syndrome. There is an innovative multidisciplinary Fitclub, which tackles the growing obesity epidemic amongst AYA in SA.

In addition, the GSH-ACE unit manages an adolescent inpatient ward at GSH. This is an incredibly valuable resource for young patients. AYA with kidney disease can be admitted to this dedicated ward where they can be co-managed by a pediatrician and an adult nephrologist to provide holistic care.

4.3 Structure of the adult service

The kidney AYA clinic, located at the adult hospital, is a continuation of the transition pathway and prioritizes adolescent advocacy. The majority of the referrals are from the pediatric service, but direct referrals from other adult services or the GSH-ACE can occur. The clinic is aimed at patients aged 13–25 years and takes place in the afternoon, which enables patients to attend school or work earlier in the day. The kidney AYA clinic has two key components: (1) a peer-mentored group session, and (2) the nephrology clinic. The peer-mentored group session is approximately 1 h in duration. It focuses on adolescent-friendly topics or social activities to enhance social connections between young people. These sessions are run by trained patient mentors who have kidney or other chronic diseases. The mentors are selected by treating clinicians based on how they engage with their kidney condition, how well they are doing on their medical treatment, the degree of maturity and if they show an interest in mentorship. With funding assistance they are formally trained in a 2-week course, run by a dedicated psychologist or social worker. They learn skills in communication, conflict resolution as well as boundary setting and group management. The mentors are supervised and debriefed after group session by a dedicated social worker, with a special interest in adolescents. Mentors also provide additional support for AYAs. This project has had a profound impact on the lives of the AYAs as well as the mentors themselves. This group has expanded its platform and now includes adolescents with other chronic conditions (HIV, diabetes mellitus, respiratory, and cardiac conditions).

The clinic visit with the nephrologist follows the group session. The clinic is designed to incorporate patients with kidney disease, irrespective of etiology or stage of CKD, including patients with ESKD on KRT. The clinic is run by a multidisciplinary team, which includes an adult and pediatric nephrologist with their respective nephrology residents, a professional nurse, a dedicated social worker and a clinical psychologist. The aim of the clinic is to provide patient-centered medical care, focusing on best clinical practice and the provision of education. It also aims to foster a supportive environment, actively addressing high-risk aspects of adolescent care. A retrospective study assessing AYA attending this nephrology service revealed the top three etiologies for patients with CKD attending the clinic to be due to glomerulonephritis, congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract (CAKUT) and hereditary conditions.27 In addition, study compared outcomes of AYAs attending the kidney AYA clinic versus the usual standard-of-care adult service. The cohort attending the kidney AYA clinic had improved kidney outcomes, lower mortality rates and less lost to follow up reported.27 One study, reviewing patients from this particular kidney AYA clinic, compared AYAs attending a recurring clinic-based peer support group versus a control group. Those that attended the peer support group had more positive attitudes toward their chronic illness, had less anxiety symptoms and were significantly less likely to screen positive for depression.41 Figure 2 illustrates this transition pathway model. The kidney AYA clinic is growing in strength and numbers.

5 CHALLENGES AND RECOMMENDATION FOR THE FUTURE

There have been many challenges in improving patient care and creating a sustainable AYA service. Table 2 highlights the challenges and possible solutions in developing an AYA service. These challenges include pediatric and adult nephrologist buy-in, access to support staff, such as a dedicated clinical psychologist, as well as institutional support and funding. An adolescent “champion” (a clinician or team member interested in adolescent care) is needed in both the pediatric and adult health care service. These “champions” provide advocacy for patients, regardless of their site of care. An additional challenge is the transition age, which requires engagement with hospital management and government policy makers.

| Challenges in adolescent care | Solutions | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Patient-related | ||

| Patient |

Interrupted schooling/education Non-adherence Engagement with high-risk behavior High rates of mental illness (depression and anxiety) Developing autonomy |

Youth-friendly environment Counseling and peer support Education Multidisciplinary support for psychosocial or psychiatric support Encouraging autonomy in treatment knowledge and decisions Promote independence |

| Parents and family |

Resistance to transition Social barriers |

Parent support group, counseling, introduction of the transition process at an early age Social worker |

| B. Health care system-related | ||

| Institutional support | Referral processes across hospitals |

“Same face in a different place” theory

Continuum of care:

Welcoming orientation at the adult center |

| Hospital management support |

Continued advocacy from pediatric and adult adolescent champions Advocacy for bidirectional transition (as necessary) |

|

| Lack of awareness | Need for better registry data on AYA outcomes | |

| Staffing | Limited staffing of adult nephrologists and heavy workload | Motivation for additional adult nephrologists in the government sector |

| Lack of funding for multidisciplinary team |

Private fundraising Task shifting – nurse/lay counselor/social worker Youth worker – counselor and advocacy member working on the continuum of care |

|

| Limited training in adolescent care | Adolescent training platforms for pediatric and adult nephrologists | |

| C. Environment-related | ||

| Social context |

Access to clinic (physical distance) High rates of poverty, substance misuse |

Dedicated social worker with a special interest in adolescence, social support grants |

| High rates of mental illness | Access to a clinical psychologist, psychiatric service with as inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy services | |

- Abbreviation: AYA, Adolescent and young adults.

This review highlights the need for a greater understanding of adolescent care in nephrology, as well as the impact of non-adherence and high-risk behavior on outcomes. Table 3 outlines key characteristics of the ideal kidney AYA transition clinic. Recommendations include building a collaborative multidisciplinary adolescent team. Our current clinical service acts as a training platform for South African and African adult and pediatric nephrology residents. This unique, shared training platform has many benefits, including (1) training all clinicians in adolescent care and addressing high-risk behavior, (2) increasing knowledge and management of rare pediatric conditions (e.g., Cystinosis, Alagille syndrome), and (3) understanding the evolution of pediatric to adult kidney disease, including the impact of pregnancy. This will allow for a smoother transition where pediatricians “let go” and adult physicians “take on” adolescent care responsibilities.

|

- Abbreviation: AYA, Adolescent and young adults.

Additional recommendations include the need for adolescent registry data on outcomes of kidney disease in LMICs. These data are vital in understanding this unique group, to improve retention and long-term kidney outcomes in AYAs living in resource-restricted areas.

6 CONCLUSION

This is the first kidney AYA clinic in Africa and has provided a clinical service for over two decades. The provision of a well-designed transitional service with adolescent advocacy at the forefront, is critical in ensuring continued adherence to treatment, especially in resource-limited settings with implications on KRT access. Kidney AYA transition clinics have the potential to improve health-related outcomes and quality of life. It is important that this process is responsive to the needs of AYAs and timing of transfer is tailored in accordance to the individuals' ability to assume an autonomous role.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.