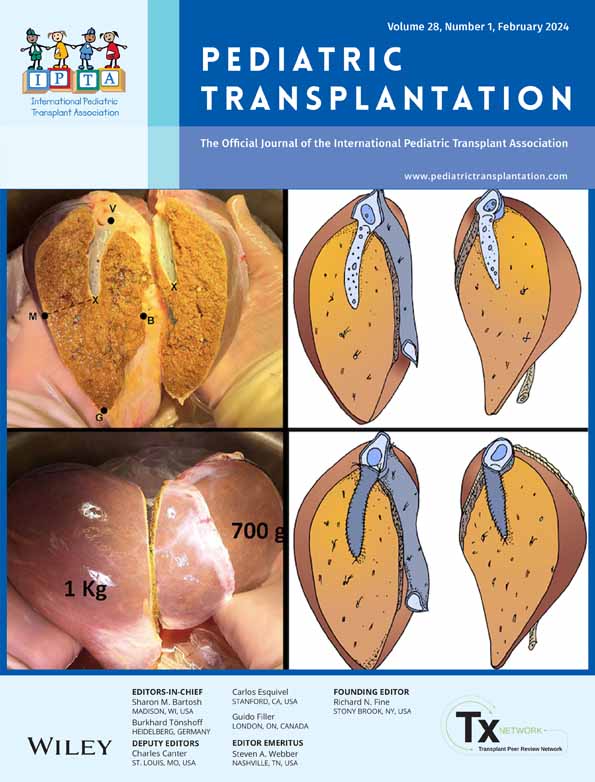

Disparity in organ distribution in Gauteng province in South Africa: Challenges and solutions

Abstract

Background

Despite South Africa's rich heritage as pioneers in organ transplantation, access to organs remains a major issue in the Gauteng province. This is secondary to an array of socioeconomic and political factors that have implications for organ distribution. Our aim was to assess the contribution of the public sector to solid organ transplantation in Gauteng province and compare the distribution of solid organs between the recipient groups.

Methods

This was a retrospective registry review of consented brain-dead donors from the public sector within Gauteng from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2021, coordinated at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital, a tertiary academic hospital.

Results

Records of 49 deceased donors were analyzed. Mean donor age was 31.5 years with the age group 30–39 years constituting the majority of deceased donors at 15/49 (30.6%); 10/49 (16%) were from pediatric donors. There was a significant discrepancy in allocation between public and private sector in cardiac (p = .012) and liver allocation (p < .001) and adult and pediatric recipients for all solid organs (p < .001). There was a significant increase in the rate and number (p = .0026) of pediatric kidney transplants occurring after March 1, 2020, when there was a transition to a public sector-mandated kidney transplant waitlist.

Conclusion

Current disparities in organ distribution have a significant impact on public sector recipients, especially pediatric patients. This is likely secondary to paucity of legislation and resource limitations which would benefit from improved governmental policies and explicit pediatric prioritization policies in transplant units.

Abbreviations

-

- CMJAH

-

- Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital

-

- NMCH

-

- Nelson Mandela Children's Hospital

-

- SA

-

- South Africa

-

- WDGMC

-

- Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre

1 INTRODUCTION

Solid organ transplantation is the standard of care for patients with end-organ failure.1 Although, South Africa (SA) has a rich heritage with major contribution as pioneers in transplantation worldwide2 and despite significant progress in the field of transplantation, access to organs remains a major challenge, particularly in the Gauteng province of SA. This is secondary to a complex array of socioeconomic and political factors that have significant implications for the distribution of organs.

One key factor contributing to this is the two-tiered healthcare system in South Africa.3, 4 The public healthcare system, which serves majority of the population, is under-resourced and overburdened, leading to longer waiting lists for organ transplantation. Public sector patients are fully funded by the government who pay the cost of the transplant as well as lifelong post-transplant care with minimal cost to the patient. The patient may be billed a minimal fee at each visit depending on their monthly earnings. In contrast, the private healthcare sector, which caters to a minority of the population with medical insurance, is well-resourced and able to provide timely access to organs.5 Private sector is funded by the patient's medical insurance by monthly self-payments to the insurance company. Depending on the medical insurance and payment plan, the transplant can either be fully or partially funded with part of the payment to the private hospital being made by the patient themselves. Some private hospitals charge above medical insurance rates for transplantation so the balance of the bill for transplantation will then have to be funded by the private patients themselves. This has led to a situation where private patients are more likely to receive organs than their public counterparts, who often face significant barriers to accessing the health care they need.6

Another factor that makes the Gauteng Province more vulnerable to disparity is the densely populated area with the majority of the transplant centers situated centrally to best serve the urban population as opposed to the rurally situated population who are also disadvantaged from a geographical location point of view.7 Additional factors that have contributed to the reduction in transplant units and training in the public sector were the legislative changes that were made at the dawn of new democracy changing focus to primary health care.8

South Africa has a legal framework for organ transplantation governed by the National Health Act of 2003,9 which largely include laws around donation (opt-in) and consent as well as organ trafficking. The current legislation regulating organ transplantation9, 10 is focused on organ and tissue donation and procurement, and does not include specific guidelines or laws on organ allocation, which are decentralized (center and province dependent). Transplant units have therefore established their own guidelines around organ allocation based on local practices and international guidelines, which are not necessarily legislated. This and the low donor rates11 have also contributed to the discrepancy in donor allocation rates between the adult and pediatric populations in addition to public and private sector patient populations.

Although children's rights in SA are protected through many legal frameworks including the constitution and international conventions,12 prioritization criteria for allocation of solid organs for pediatric patients are not legislated and are center and sector dependent. The prioritization of pediatric renal patients in the public sector after March 2020 was due to the renal transplant program in CMJAH becoming autonomous and independent from the private sector due to training of public sector-based renal transplant surgeons. This allowed the public sector transplant team autonomy in setting up separate guidelines for the CMJAH transplant unit which prioritized pediatric patients going forward. Prioritization guidelines for other pediatric solid organ transplants are currently not established or legislated.

Our aim was to assess the contribution of the public sector to solid organ transplantation in the Gauteng province and to assess and compare the distribution of solid organs between the various recipient groups.

2 PATIENT AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and population

This study was a retrospective registry review of consented brain-dead donors from state sector within the Gauteng Province from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2021. In this period, there were 49 consented donors which were all included in our study population. Brain-dead donors who did not meet the criteria for brain death or for whom consent was not obtained were excluded from our study.

Brain death by neurological criteria was defined as the complete, irreversible cessation of all brain function and confirmed as per criteria in the consensus document: South African Guidelines on the determination of death.13 Pediatric patients were defined as any patients less than or equal to 18 years of age, and adult patients were defined as any patients older than 18 years of age.

2.2 Study procedure

Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) is a tertiary academic hospital in Parktown, Johannesburg, which co-ordinates transplant procurement for public sector donors from various public sector hospitals throughout the province via the Gauteng Solid Organ Provincial transplant coordinator team. The procurement team at CMJAH is responsible for updating all donor information into the registry which is securely kept at CMJAH.

Currently, in the Gauteng Province, there is only one transplant center for the cardiac and lung (double lung) transplant program which is mandated at Netcare Milpark Hospital (a private hospital). Patients are listed monthly by means of a peer review and panel meeting. Allocation is made by a multidisciplinary team in private sector and based on blood group, age, gender, height, weight, and tissue typing. There is currently no public sector cardiac and lung transplant program in the Gauteng Province. There is also currently no pediatric cardiac or lung transplant program in the Gauteng province.

Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre (WDGMC), a private academic hospital, is the only transplant center performing liver transplantation in the Gauteng Province.14 Listing panels are held weekly and there is a separate waiting list for adult and pediatric liver recipients based at WDGMC. Public and private sector liver recipients are placed on a combined waitlist. Liver allocation for both pediatric and adult, public and private sector patients, is done by the private sector transplant team at WDGMC based on the Pediatric End-stage liver disease (PELD) and the Model for End-stage Liver disease (MELD) system of allocating to the sickest patient first. Allocation parameters other than MELD/PELD are not available and there is no consistency regarding the exceptions. There is no explicit consideration for pediatric priority in liver allocation, which is done by the surgical team in the private sector at WDGMC. Currently, there is no multidisciplinary team comprising of public and private sector involved in liver allocation. Although everyone is equally eligible for listing if they fulfill transplant criteria and the transplant listing panel (multidisciplinary team from public and private sector) agrees, there is no committee deciding priority on the waitlist, and the only firm criteria are PELD/MELD or if patients are on the national priority list for fulminant liver failure, hepatic artery thrombosis, or primary nonfunction. All public sector patients receive liver transplantation at WDGMC at a subsidized rate funded by the government based on a public–private collaboration between CMJAH and WDGMC.15

There are multiple hospitals in Gauteng where renal transplantation is being performed, both in public and private sector. There are currently five renal allocation lists in the Gauteng Province. In Johannesburg, the public sector and WDGMC have separate waitlists since March 2020 and Netcare private hospital group, since Nov 2020. Prior to this, there was a combined renal allocation list for all these entities based at WDGMC. There are also two separate waitlists in Pretoria, Gauteng (for public and private sector renal patients). Separate panel meetings are held monthly, and new patients are listed on the various lists. The renal allocation system is multidisciplinary and based on blood group, age of the donor and tissue typing, and waiting period on the waitlist. Since March 2020, the public sector renal panel decided to prioritize pediatric patients and any donor kidney less than 25 years of age would be offered to a suitable pediatric donor initially, prior to an adult donor. The first five slots for every blood group were also allocated to pediatric recipients. Within the Gauteng province, pediatric renal transplantation only occurs in Johannesburg (CMJAH, WDGMC, and Nelson Mandela Children's Hospital [NMCH]) and pediatric liver transplantation only at WDGMC.

There is no certainty regarding whether all organs are a public resource or “proprietary” as the South African legislation does not specify this.16 It is not “proprietary” as even organs procured from the public sector are “governed” by the private sector surgeons as they are the only ones who have the skills in transplanting certain solid organs, for example, liver.

Data collected included donor and recipient demographics including age, gender and of the donor, type of organ procured, distribution of organs between private and public sector, and adult and pediatric. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Witwatersrand (Medical) (M211045).

2.3 Statistical methods

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normality of continuous variables. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were described using the median and interquartile range, while normally distributed variables were described using the mean and standard deviation. Categorical data were described using frequencies and percentages. The Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA compared medians of continuous variables between categorical variables with two groups and those with three or more groups, respectively. The independent t-test compared means across categorical variables with two groups. Visual graphics such as bar graphs and box and whisker plots were used to summarize and organize continuous variables where applicable. Pearson's chi-squared test compared proportions between categorical variables; otherwise, Fischer's exact was used for sparse data. Analyses were done in Stata 14, and statistical significance was set at 5%.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Donor characteristics

The records of 49 deceased donors were reviewed and analyzed. The mean donor age at the time of death was 31.5 years with the age group 30–39 years, constituting the majority of deceased donors at 15/49 (30.6%). Ten (16%) were from pediatric donors less than 18 years of age. Most donors were male (75.5%) with African and White races contributing the most donations at 43% and 41%, respectively (Table 1). There was a total of 84 kidneys, 38 whole livers, 12 split liver lobes, 4 pancreases, 15 hearts, and 12 double lungs donated with a mean of 3.37 ± SD 1.2 organs donated per donor (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Total n = 49 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Donor age at the time of death/(years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 31.5 ± 14.8 |

| Donor age categories | |

| <10 | 2 (0.04%) |

| 10–18 | 8 (16%) |

| 19–29 | 12 (24.4%) |

| 30–39 | 15 (30.6%) |

| 40–49 | 4 (8.2%) |

| 50+ | 8 (16.3%) |

| Donor sex | |

| Female | 12 (24.5%) |

| Male | 37 (75.5%) |

| Donor race | |

| African | 21 (42.9%) |

| Mixed race | 7 (14.3%) |

| Indian | 1 (2.0%) |

| Caucasian | 20 (40.8%) |

| Donor metrics (excluding discarded) | |

| Total solid organs donated per donor | 3.37 ± 1.2 |

| Number of individual kidneys | 84 |

| Number of whole livers | 38 |

| Number of split liver lobes | 12 |

| Number of pancreases | 4 |

| Number of hearts | 15 |

| Number of double lungs | 12 |

3.2 Distribution of organs between pediatric and adult recipients

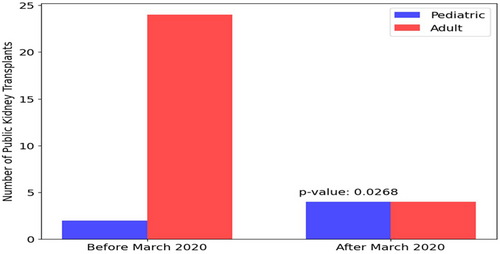

The mean age of recipients receiving livers procured during our study was 30.89 years (±17.10) with adult recipients receiving a significantly larger number of liver transplants compared with pediatric recipients (p < .001) (Table 2). This was found in all other solid organs transplanted (Table 2). There was a significantly larger proportion of kidneys allocated to adult recipients compared with pediatric recipients in the public sector (p < .001) (Table 2). Most pediatric renal transplants were performed after March 2020 when public sector kidney transplantation became independent from a private sector-based wait list and allocation system. The number and rate of pediatric kidneys compared with adult kidneys transplanted in public sector before: 2/26 (7.69%) and after: 4/8 (50%), March 2020, was also found to be statistically significant (p = .027) (Figure 1).

| Organ | Total organs used | Recipient age (mean) | Pediatrics N (%) | Adults N (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 38 whole 12 split lobes | 30.89 ± 17.10 | 11 (22) | 39 (78) | <.001 |

| Livera | 38 | 4(10.5) | 34(89.5) | <.001 | |

| Kidney (K1) | 42 | Unavailable | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.4) | <.001 |

| Kidney (K2) | 42 | Unavailable | Unavailable | Unavailable | Unavailable |

| Pancreas | 4 | Unavailable | 0 | 4 (100) | .028 |

| Heart | 15 | Unavailable | 0 | 15 (100) | <.001 |

| Lungs | 12 double | Unavailable | 0 | 12 (100) | <.001 |

- a Excludes split livers and unsuitable livers.

3.3 Distribution of organs between public and private sector

Fifteen (15/49: 30.6%) donor hearts were suitable for cardiac transplantation with 12/15 (80%) allocated to private sector recipients in a Johannesburg hospital and the rest to public sector (Cape Town). Lungs were equally distributed to all adult recipients between private sector in Gauteng (7/12: 58.3%) and public sector in Cape Town (5/12: 41.7%) (Table 3). Most livers procured were used for transplantation with 5/49(10.2%) found to be unsuitable. Thirty-three livers (86.8%) were used for recipients in the private sector with 5/38 (13.2%) used for public sector patients (Table 3). Six (15.8%) livers were split and donated equally between private and public sector patients. Two kidneys were donated from each of the 49 donors (Table 1). Two pairs were from HIV-positive donors and sent to public sector in Cape Town for the HIV-positive to positive kidney transplant program. Four pairs of kidneys were found to be unsuitable for transplantation. One kidney (K1) was predominantly allocated to public sector patients at 73.8%, while the other kidney predominantly to private sector patients at 97.6% (Table 3). Four kidneys (9.3%) were used for combined kidney–pancreas transplantation of which all the recipients were private-sector adult patients (Table 2). There was a statistically significant discrepancy in allocation between public and private sector in cardiac (p = .012), pancreas, and liver transplantation (p < .001) (Table 3).

| Organ | Total | Public | Private | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livera | 38 | 5 (13.2%) | 33 (86.8%) | <.001 |

| Liverb | 50 | 9 (18%) | 41(82%) | <.001 |

| Pancreas | 4 | 0 | 4 (100%) | <.001 |

| Kidney (1) | 42 | 31 (73.8%) | 11 (26.1%) | <.001 |

| Kidney (2) | 42 | 1 (2.4%) | 41 (97.6%) | <.001 |

| Heart | 15 | 3 (20%) | 12 (80%) | .012 |

| Lung pairs | 12 | 5 (41.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | .683 |

- Note: All values in bold are statistically significant as p < .05.

- a Excludes unsuitable livers and organs donated to both sectors like split livers.

- b Includes whole and split livers.

3.4 Distribution of various solid organs

Twenty-seven: 27/44(61%) donor livers procured from the public sector during this study period were from donors younger than 40 years of age. Six: 6/27(22.2%) of these were split. Of the livers that were not split, 4/39 (10%) were allocated to pediatric recipients. Ten (20.4%) livers were procured from pediatric recipients (Table 4), one of which were split (two lobes). Pediatric patients received four whole livers and seven lobes (split livers), so the donor and recipient numbers in pediatric livers in our cohort were relatively equal. The median age of liver transplant recipients was higher in the private sector at 45 years (IQR: 39–59) compared with the public sector at 21 years (IQR: 17–34), and this difference was statistically significant (p = .044) (Figure S1).

| Date year | Donor age (years) | Recipient age (years) | Type of liver | Sector | Kidney 1 sector | Kidney 2 sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 4 | 32 | Whole | Private | Public adult | Privatea |

| 2017 | 4 | 1.1 | Whole | Private | Privatea | Privatea |

| 2017 | 18 | 21 | Whole | Public | Public adult | Privatea |

| 2018 | 18 | 73 | Whole | Private | Public adult | Privatea |

| 2018 | 13 | 2 and 18 | Split | Private/public | Public adult | Privatea |

| 2018 | 18 | 2 | Whole | Public | Public adult | Privatea |

| 2019 | 18 | 50 | Whole | Public | Privatea | Privatea |

| 2019 | 14 | 44 | Whole | Private | Privatea | Privatea |

| 2020 | 16 | 17 | Whole | Public | Unsuitable | Unsuitable |

| 2020 | 16 | 40 | Whole | Private | Public pediatric | Privatea |

- a No data are accessible on whether the kidney was allocated to pediatric or adult private. All allocation for kidney and liver organs procured was done by private sector surgical team. Kidney allocation changed to multidisciplinary public sector team in March 2020.

Public sector kidneys procured from pediatric patients were a total of 20/84 (23.8%) kidneys from 10 pediatric donors (Table 4). Six pediatric patients received kidney transplants in public sector from the cohort. Unfortunately, data from private-sector kidney transplants are unavailable.

Of the 10 pediatric donors, 3/49(6%) hearts were used for adult heart transplantation and no pediatric patients received cardiac transplantation from our cohort of donors. One set of double lungs was procured from the 10 pediatric donors and used for lung transplantation in an adult recipient.

4 DISCUSSION

Significant disparity exists in the distribution of solid organs in the Gauteng Province in SA. This is the first report on the distribution of solid organs in the Gauteng province procured from the public sector. Despite being the smallest province in SA, Gauteng is the most densely populated and urbanized province17 and houses a population of about 15 million of the 59 million population of SA. Johannesburg is the biggest city in Gauteng18 and the location of CMJAH, a public sector tertiary academic hospital where this study was coordinated.

South Africa's current healthcare system is two-tiered with an obvious gap between public and private health services,3, 19 with more than 80% of the population accessing public health care, which is government-funded.20 This is an extremely under-resourced healthcare system with many public hospitals facing resource limitations (including skilled personnel)2, 3 and long wait list times as compared to the private healthcare system (self-funded), which is well-resourced and comparable to healthcare institutes in high-income countries. Lack of education of healthcare workers in terms of timeous referral of patients in need of transplantation and lack of sufficient numbers of trained personnel contribute to this resource limitation (lack of skilled staff and technology) which negatively impacts solid organ transplantation in public sector patients. This is emphasized by our study findings with public sector and pediatric patients with end-organ failure having limited access and opportunities for transplantation. In our cohort, pediatric donors accounted for 20% of total donors, and accounted for 18.8% and 22% of kidney and liver recipients, respectively.

The liver transplantation service in Gauteng is a good example of the skewed resources between private and public sector health care in SA. Currently, there are only two liver transplantation centers in SA,14 with WDGMC, a private academic hospital, in Johannesburg being the only center where living donor, split, and ABO incompatible liver transplantation is performed. There are currently no skilled liver transplant surgeons in the public sector hospitals in the Gauteng province, despite many transplant surgeons having completed their surgical training time in public sector hospitals. Compensation packages and resources in private hospitals are more lucrative resulting in an exodus of skilled surgeons from the public to private sector hospitals21, 22 in Gauteng.

A private–public collaboration between WDGMC and CMJAH was established to mitigate the skewed resources and to assist public sector patients in accessing liver transplantation.15 This partnership has predominantly benefitted the pediatric patients in the public sector, especially since 2015, when a functional pediatric hepatology unit was established at CMJAH. Although CMJAH is a public sector government hospital, with a lack of skilled surgeons to perform liver transplantation, all other expertise to manage pediatric liver transplant recipients is available. In our study period, despite more public sector pediatric patients receiving liver transplants, the deceased donor allocation to public sector patients including pediatric patients, was significantly lower compared with private sector patients. The increase in pediatric liver transplants in public sector patients was largely due to related living donor liver transplantation which accounts for >50% of pediatric liver transplants performed at WDGMC.4 The allocation of deceased donor livers, whether procured from public or private sector, is done by the private sector transplant surgical team working at WDGMC. Both CMJAH and WDGMC fall under the academic auspices of the University of Witwatersrand.

At any given point in our study period, there were more than 50% of public sector pediatric patients on the combined active waitlist for liver transplantation. An annual review on liver transplantation data in 2020 published by Bouter et al. from the private sector WDGMC transplant team included an audit of all liver transplants (public and private) done at WDGMC from 2016 to 2020 which correlates with the timeline of our study. This audit showed that the waitlist mortality for pediatric patients was found to be double that of the adult recipients (22% vs. 10.7%), and it was also found that 41% of pediatric patients transplanted had a PELD score between 15 and 29 compared with 93.7% of adult patients receiving liver transplants with a MELD <15. Although more living-related donor transplants were performed for pediatric patients, adult patients received more deceased donor transplants and spent less time on the waitlist compared with pediatric patients.23 This audit emphasizes the lack of explicit pediatric prioritization in liver allocation in Johannesburg resulting in poorer outcomes for waitlisted pediatric patients.

Cardiac and lung transplant centers24 are based at a private hospital in Johannesburg, called Milpark Hospital. Although there is currently no cardiac or lung transplantation being performed in the public sector or for pediatric patients, many patients who no longer have medical insurance after their transplants in the private sector are transitioned to CMJAH who assist with resources for their long-term follow up. Despite the first cardiac transplantation being performed in a public sector hospital in the Western Cape in SA in 1967 by Dr Chris Barnard,25 momentum has been lost and resource limitation largely due to financial constraints would be the major reason the public sector hospitals in the Gauteng province are not performing heart and lung transplantation, hence allocation of these organs is largely skewed in favor of the private sector population.

The first renal transplant was performed in Johannesburg in 1966 by Thomas Starzl and Bert Myburg at the Johannesburg Hospital (now known as CMJAH).2, 26 Since 2000, renal allocation policies in Johannesburg have tried to iron out the discrepancies previously present, to the benefit of public sector patients. One kidney would always be allocated to a public sector patient irrespective of which sector the kidney was procured from.2 This is the reason why there is a largely equal distribution between private and public patients with regard to renal allocation. Pediatric patients, however, were not being explicitly prioritized when the Johannesburg renal waitlist was being mandated by WDGMC until March 2020. This is consistent with studies from many low-middle-income countries.27, 28 Since March 2020, when the public sector waitlist became autonomous with our public sector surgeons performing kidney transplantation at CMJAH, an increased number of pediatric patients received kidney transplantation as compared to previously, in keeping with newer public sector guidelines prioritizing pediatric renal recipients. This resulted in a significant increase in renal transplantation in pediatric public sector recipients since the implementation of explicit pediatric prioritization.

The collaboration between CMJAH and NMCH, a tertiary pediatric hospital situated near CMJAH, has positively contributed to the increase in pediatric transplant numbers. NMCH is a trust-funded pediatric hospital which serves both public and private sector pediatric patients and has state-of-the-art intensive care facilities and resources29 that have assisted in improved outcomes for pediatric renal transplant recipients in the public sector. The surgical team from CMJAH is responsible for pediatric renal transplantation at NMCH. The allocation criteria in public sector were adjusted to prioritize pediatric patients. Kidneys from deceased donors younger than 25 years of age would be allocated preferentially to a pediatric recipient. On the top 30 lists, the first five slots for each blood group would be occupied by potential pediatric recipients first, followed by adult recipients. This has all contributed to a marked increase in pediatric kidney transplants in the public sector since March 2020.

There has been an increased focus on educational campaigns30 in the form of online webinars, for staff involved in public sector hospitals and primary-level facilities, to improve education regarding the availability of transplantation and referral pathways in solid organ transplantation. The pediatric webinar series called; “Transplant saved my baby” has served as a national outreach platform where we have managed to educate healthcare workers based in outlying areas. This has not only increased the referral of patients but also sparked an interest in medical personnel in seeking training and expertise in the field of transplantation. The utility of online webinars and awareness campaigns30 by transplant coordinators and educators31 and the employment of link nurses has also been undertaken in public sector hospitals to increase deceased donor referrals and the rate of consent for deceased donor organs.32 Collaboration opportunities with established international transplant units have also been embarked on with the purpose of increasing the surgical skills and expertise in public hospitals,33 and assisting in removing these inequities in organ distribution.

4.1 Limitations

This was a retrospective study with information acquired from the public sector registry, so only information on solid organs procured from the public sector in Gauteng was considered. This study did not include organs procured from the private sector in the Gauteng region and their distribution. This information would be more useful in formulating definitive conclusions regarding allocation and distribution of all organs procured from the Gauteng province.

5 CONCLUSION

South Africa is an interesting country steeped in immense inequality from our racialized history of unequal health care secondary to apartheid governmental policies.5, 34 Our current disparities in organ distribution and allocation have had a significant impact on both public sector and pediatric recipients and are largely secondary to paucity of legislation9, 10 and resource limitations, which would benefit from improved governmental policies and the implementation of national health insurance.35, 36 Recognizing that the implementation of government legislation may take some time, as an interim measure, we recommend the introduction of a multidisciplinary panel to assist in the decision-making process. Explicit pediatric prioritization as adopted in our current public sector pediatric renal transplant program, has made an immense positive contribution to pediatric renal transplantation and should be modeled in allocation policies for all solid organs. A transparent, equitable allocation system would mitigate the current disparity in organ distribution in the Gauteng province in SA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PW contributed to the conception of the study, acquisition, and interpretation of data, drafting of first and subsequent drafts, and final draft of the manuscript. STP contributed to the interpretation of data and approval of final manuscript. CH contributed to the approval and adjustment of final draft and manuscript. AM contributed to the conception of the study, acquisition and interpretation of data, and approval of the first and final draft of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all donors and their families, members of Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital Transplant Unit, and for Dr Faith Moyo for assistance with the statistical analysis.

FUNDING INFORMATION

There is no funding source for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of HREC of the University of Witwatersrand and with the Declaration of Helsinki standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.