Japanese pediatric guideline for the treatment and management of bronchial asthma 2012

Abstract

A new version of the Japanese pediatric guideline for the treatment and management of bronchial asthma was published in Japanese at the end of 2011. The guideline sets the pragmatic goal for clinicians treating childhood asthma as maintaining a “well-controlled level” for an extended period in which the child patient can lead a trouble-free daily life, not forgetting the ultimate goal of obtaining remission and/or cure. Important factors in the attainment of the pragmatic goal are: (i) appropriate use of anti-inflammatory drugs; (ii) elimination of environmental risk factors; and (iii) educational and enlightening activities for the patient and caregivers regarding adequate asthma management in daily life. The well-controlled level refers to a symptom-free state in which no transient coughs, wheezing, dyspnea or other symptoms associated with bronchial asthma are present, even for a short period of time. As was the case in the previous versions of the guideline, asthmatic children younger than 2 years of age are defined as infantile asthma patients. Special attention is paid to these patients in the new guideline: they often have rapid exacerbation and easily present chronic asthmatic conditions after the disease is established.

The Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JSPACI) published the first guideline for childhood asthma (“Japanese pediatric guideline for the treatment and prevention of bronchial asthma” [JPGL]) in the year 2000. It was revised three times (2002, 2005, 2008), each in response to the progress in the strategy of asthma management and also to the introduction of new medications into clinical practice.1, 2 Also, the mortality from asthma-related events has been in decline. During more than 3 years since the last revision (JPGL2008), asthma mortality in the pediatric age group showed a further decrease. The year 2010 had only 10 patients younger than 19 years of age who died from asthma-related events. The JPGL thus plays an important role in the treatment and management of childhood asthma in this country.

From the therapeutic point of view, the concept of controlling asthma-related symptoms at a satisfactory level has been accepted as an important strategy for long-term asthma management.3 In the new version of the guideline, JPGL2012, this internationally adopted concept is accepted as mostly valid in Japan as well; however, we pediatricians should always set our ultimate goal at a higher level.4

Definition, pathophysiology, diagnosis and classification

Childhood asthma is defined as a respiratory disease that presents repeated wheezing, dyspnea and prolonged expiration time by paroxysmal airway constriction. Although these symptoms usually resolve or disappear in time without any treatment or by medical intervention, death occurs on rare occasions. Airway constriction is caused by airway smooth muscle contraction, submucosal edema and hyper-excretion from mucosal glands. Fundamental pathophysiology is airway hyper-responsiveness closely associated with chronic airway inflammation that results in irreversible structural changes, such as smooth muscle hyperplasia, mucosal fibrosis and thickening of the basement membrane (airway remodeling). Childhood asthma is considered to develop from genetic traits in conjunction with environmental factors.5 In a large population of asthma patients, immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated allergic reaction is an initial step of airway inflammation that induces infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, Th2 lymphocytes, mast cells and eosinophils, which in turn release various cytokines, chemokines and chemical mediators.6-12 Once airway hyper-responsiveness is established, various exacerbating factors, including tobacco smoke, cold air, and virus infection, can cause asthma symptoms to surface; that is, symptoms associated with airway constriction and airflow limitation. Although it has been reported that airway remodeling is found in childhood asthma, it is not clear whether the remodeling is the result of chronic inflammation or it develops by other independent mechanisms.13-15

A diagnosis of childhood asthma is made on the basis of the patient's history, clinical symptoms, respiratory functions and allergic predisposition, after exclusion of other respiratory and cardiac diseases indicating similar clinical symptoms and signs.

Childhood asthma is a heterogeneous disease that presents a variety of pathophysiological conditions. In most of the patients with childhood asthma, specific IgE antibodies to airborne antigens are elevated (atopic asthma), while in some patients those specific antibodies are not found (non-atopic asthma). In Japan, mites in house dust are the most common and significant antigens in atopic asthma. Recently, however, different asthma phenotypes in the infantile period have been discussed. Martinez et al. classify wheezing infants into three subtypes: transient early wheezers, non-atopic wheezers and IgE-associated wheezers.16 Brand et al., on the other hand, classify wheezes that infants present with into two subtypes: multi-trigger wheeze and episodic (viral-induced) wheeze.17 In JPGL2012, a diagnosis of infantile asthma is made when an episode of wheezing in the expiratory phase occurs three times independently, regardless of complications due to respiratory infection. Infantile asthma based on the JPGL may therefore include various pathophysiological conditions.

Asthma severity

In asthma severity, JPGL2012 follows the classification of the previous version, JPGL2008, which consists of intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent asthma. Asthma severity is basically evaluated in the absence of controller (for long-term management) drugs. Long-term management in the JPGL2012 guideline is divided into four steps that match the respective ranks of the severity of asthma. If controller drugs are already prescribed, the “true” asthma severity should be determined with the present treatment taken into consideration. For example, even if the “apparent” severity of a patient in treatment step 2 is determined as mild persistent, the “true” severity should really be moderate persistent, which is what their intersection point – mild persistent asthma and step 2 – represents (Tables 1, 2).

| Asthma severity | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Intermittent | Seasonal cough and/or wheeze (2–3 times/year). Sometimes dyspnea also, but recovers soon with SABA |

| Mild persistent | Cough and/or mild wheezing; more than 1/month, less than 1/week. Sometimes dyspnea also, but it does not continue for long enough to disturb daily life |

| Moderate persistent | Cough and/or mild wheezing; more than 1/week, but not everyday. Sometimes progresses to moderate to severe exacerbation, and disturbs daily life |

| Severe persistent | Cough and/or mild wheezing occurs everyday. Moderate to severe exacerbation occurs 1–2/week, disturbing daily life and sleep |

| Most severe persistent (sub-class) | Asthma symptoms continue despite the treatment for severe persistent asthma. Frequent asthma exacerbations requiring treatment at emergency room and hospitalization. Daily life is disturbed to a large extent |

- SABA, short-acting β-agonist.

| Asthma severity decided from patient's symptoms without considering current treatment-step | Current treatment-step | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

| Intermittent asthma | Intermittent asthma | Mild persistent | Moderate persistent | Severe persistent |

| Mild persistent asthma | Mild persistent | Moderate persistent | Severe persistent | Severe persistent |

| Moderate persistent asthma | Moderate persistent | Severe persistent | Severe persistent | Most severe persistent |

| Severe persistent asthma | Severe persistent | Severe persistent | Severe persistent | Most severe persistent |

A comparison of ranks of asthma severity between JPGL2012 and international guidelines, such as those by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and the Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3), reveals one-stage differences: intermittent, mild persistent, and moderate persistent in GINA, for example, approximately correspond to mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent in the JPGL2012. Severe persistent in the GINA guidelines and the EPR-3 is close to the “most severe persistent” sub-group in the severe persistent rank of the JPGL2012. In the case of symptoms occurring less than once a week, the grade is taken as intermittent in both the GINA and EPR-3 guidelines, but it is mild persistent in the JPGL2012. This scheme makes the JPGL more useful in the management of childhood asthma because it helps the clinician diagnose the disease earlier and begin the treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs sooner.

Epidemiology of childhood asthma

Prevalence of childhood asthma

In this country, the prevalence of asthma as determined by the American Thoracic Society – Division of Lung Diseases is 2.8–6.5%. The prevalence in school children has been increasing in the last 2 decades according to a survey targeting children at the same elementary schools in the same area.18 In general, data shows the following: (i) asthma is more common among juveniles, particularly among male children, and more specifically among male infants; (ii) the prevalence varies twofold or more between regions; and (iii) the prevalence is higher in children with a family history of allergic diseases. Children with a higher body mass index (>90th percentiles) indicate higher prevalence of asthma from infancy to adolescence.19 Prevalence of childhood asthma in Japan is ranked at the middle of various countries in the world.

Complications

Allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and atopic dermatitis are common as coexisting allergic diseases caused by the same mechanism as asthma. Their respective complication rates are 52.8%, 24.4% and 30.9%.20

Death from asthma

Mortality from asthma during childhood has markedly decreased throughout the years since the publication of the JPGL. The number of deaths in patients with asthma aged 0–19 years was 10 in 2010.21 Suffocation is the leading cause of death in acute asthma exacerbation. Death occurs mostly in patients with severe persistent asthma, but sometimes patients with moderate or mild persistent asthma also die from its exacerbation.

Prognosis

The remission rate is lower in cases that are more serious in severity. Remission is defined as an asymptomatic status without any treatment. A remission status that continues for 5 years or longer is considered a clinical cure. Furthermore, if respiratory function and airway hyper-responsiveness recover to normal levels, the status is determined as functional cure.

Risk factors and prevention

Childhood asthma is considered to originate from genetic traits that are prone to produce IgE against allergens. At the same time, various environmental risk factors are at work, such as respiratory infections, exercise, tobacco smoking, weather conditions and air pollution. Eliminating exacerbating factors from the immediate environment of each patient is essential to the prevention and management of asthma. It is therefore extremely important that a clinician take the patient's history carefully to identify specific allergens and exacerbation factors. Also, for primary prevention, it is strongly recommended that a patient avoid active and passive smoking. For secondary and tertiary prevention, the patient must avoid inhalation of allergens, including house dust mites, as well as other non-specific irritants, such as tobacco smoke and chemical substances. Respiratory viral infections, specifically from rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus, are obvious risk factors for asthma development and asthma exacerbation.22-25

According to some reports, inhaled glucocorticosteroid may not change the natural course of childhood asthma, but it does prevent asthma exacerbation, leading to improved quality of life (QOL).26

Respiratory function and other indices for diagnosis of asthma and its severity

Respiratory function tests and other objective indices are useful for diagnosis, decision on treatment step, and monitoring of control levels. Spirometric measurement, peak flow meter monitoring, and blood gas analysis give data with which to assess airflow limitation. Nitric oxide (NO) concentration in expiratory breath by NO analyzer and cell classification analysis in sputum reflects airway inflammation. Airway hyper- responsiveness is determined by detection of the concentration at which forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) starts decreasing when gradually increasing concentrations of methacholine, acetylcholine or histamine are inhaled.

The impulse oscillometry analyzer has been introduced into the practice of pediatric respiratory medicine, which offers the possibility of detecting segmental airway obstruction.27

Acute exacerbation and treatment

Intensity of asthma exacerbation is determined by respiratory conditions, including results of respiratory function tests, level of consciousness, and living matters, such as state of speaking, feeding and sleeping. Measurement of percutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2) is another important index that indicates the intensity of asthma exacerbation. The intensity is classified into four levels: mild exacerbation, moderate exacerbation, severe exacerbation, and respiratory failure. The criteria by which to judge intensity of asthma exacerbation are shown in Table 3.

| Component | Mild exacerbation | Moderate exacerbation | Severe exacerbation | Respiratory failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory status | Wheezing | Mild | Apparent | Marked | Reduced or eliminated |

| Retractive breathing | None–mild | Apparent | Marked | Marked | |

| Prolonged expiration | (−) | (+) | Apparenta | Marked | |

| Orthopnea | Can lie down | Prefers sitting position | Bends forward | ||

| Cyanosis | (−) | (−) | Possibly(+) | (+) | |

| Respiratory rate | Slightly increased | Increased | Increased | Undetermined | |

| Normal respiratory rate | <2 months <60/min | 2–12 months <50/min | 1–5 years old <40/min | 6–8 years old <30/min | |

| Feeling of dyspnea | During rest | (−) | (+) | Marked | Marked |

| During walking | (+) When in a hurry | Marked during walking | Difficulty in walking | Cannot walk | |

| Daily life | Speech | Pause after one sentence | Pause after phrases | Pause after one word | Impossible |

| Diet | Almost normal | Slightly difficult | Difficult | Impossible | |

| Sleep | Can sleep | Occasionally wake up | Disturbed | Disturbed | |

| Impaired consciousness | Excitation | (−) | Slightly excited | Excited | Confused |

| Lowering of consciousness | (−) | (−) | Slightly lowered | (+) | |

| PEF | (Before β2 inhalation) | >60% | 30–60% | <30% | Unmeasurable |

| (After β2 inhalation) | >80% | 50–80% | <50% | Unmeasurable | |

| SpO2 (room air) | ≥96% | 92–95% | ≤91% | <91 | |

| PaCO2 | <41 mmHg | <41 mmHg | <41–60 mmHg | >60 mmHg |

- a Difficult to determine during tachypnea. During strong exacerbation, the expiratory phase is at least twice as long as the inspiratory phase. There are several criteria. It is not required that all criteria be met. As intensity of exacerbation increases, infants present with seesaw breathing, not shoulder breathing. During expiration and inspiration, distention and depression of the chest and abdomen repeat like a seesaw. Exclude intentional abdominal breathing. PaCO2, carbon dioxide partial pressure; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Treatment of asthma exacerbation at home

First of all, what is important is to fully educate patients and/or caregivers on how to correctly determine the signs and symptoms of critical levels of exacerbation. In the absence of signs of critical levels of exacerbation, the patient can be treated with inhalation of β-2 agonist at home, followed by observation. The patient should be taken to medical facilities without delay when dyspnea continues or worsens. Taking earlier, often immediate, action is recommended in babies and infants. When the patient exhibits signs of critical levels of exacerbation, he/she should be taken to emergency hospital, and on the way there, inhalation treatment with β-2 agonist can be repeated every 20–30 min. Prompt action is compulsory in severe exacerbation and respiratory failure.

Treatment of asthma exacerbation at the hospital

If a patient is at moderate or severe exacerbation level, or in respiratory failure, he/she should be treated at the hospital. Once at the emergency department, the intensity, duration and cause of exacerbation should be assessed. The patient's history of exacerbation and medical treatment on such occasions is also evaluated before a treatment plan is determined. For evaluation of the exacerbation level, measurements of SpO2 and peak expiratory flow (PEF) are useful besides clinical signs and symptoms. Drug-based treatment plans according to the intensity of asthma exacerbation are shown in Table 4.

| Mild exacerbation | Moderate exacerbation | Severe exacerbation | Respiratory failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | β2 agonist inhalation |

O2 inhalation (SpO2 > 95%) Repeated β2 agonist inhalation† |

Hospitalization O2 inhalation, intravenous infusion Repeated β2 agonist inhalation† or Continuous isoproterenol inhalation Steroid administration Consider continuous infusion of aminophylline |

Hospitalization O2 inhalation, intravenous infusion Continuous isoproterenol inhalation Steroid administration Continuous infusion of aminophylline Consider ventilation under respirator |

| Additional treatment | Repeated β2 agonist inhalation† |

Steroid administration (intravenous infusion or oral administration) Aminophylline‡ (intravenous or continuous infusion) Consider hospitalization |

Increased dose of continuous isoproterenol inhalation Ventilation under respirator |

Increased dose of continuous isoproterenol inhalation Ventilation under respirator Acidosis correction Consider anesthesia |

- †Every 20–30 min; total up to 3 times. ‡Intravenous infusion of aminophylline should be done by experts for childhood asthma.

Moderate intensity of exacerbation

An initial treatment is inhalation of β-2 agonist (0.1–0.3 mL for babies and infants, 0.3–0.5 mL for school children) to keep SpO2 higher than 95% with or without oxygen. Beta-2 agonist is repeatedly inhaled every 20–30 min, maximally 3 times.

Intravenous injection or per-oral administration of glucocorticosteroid is considered as an additional treatment. Continuous infusion of aminophylline is another option. But to avoid side-effects, it is recommended that the serum concentration of aminophylline be kept at 8–15 μg/mL. The use of aminophylline is not recommended for infants younger than 2 years of age. Patients who are 2 years old or over who respond well to the treatment can be returned home. Regardless of their age, infants who do not respond to the treatment should be admitted to the hospital for further treatment.

Severe intensity of exacerbation and respiratory failure

Inhalation of β-2 agonist with oxygen should begin immediately. Continuous inhalation of isoproterenol with oxygen is an alternative treatment when patients do not respond well to repeated inhalation of β-2 agonist. Intravenous injection of glucocorticosteroid should be simultaneously started and continuous infusion of aminophylline should also be considered. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation must be considered when respiratory condition fails to improve.

Long-term management by pharmacotherapy

Although the ultimate goal of asthma therapy is to obtain functional remission and/or cure, maintaining a patient at a well-controlled (symptom-free) level by suppressing chronic airway inflammation for a long-enough period is the pragmatic aim of the treatment and management of childhood asthma in daily life. Essential to that end is an adequate management against acute exacerbation and a good strategy to weaken environmental risk factors, like mites in house dust. The most important and effective strategy, however, is to use anti-inflammatory drugs appropriately according to the patient's asthma severity. As said before, asthma severity is classified into four levels: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent. These levels respectively correspond to treatment steps 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the pharmacotherapy plan for long-term management of childhood asthma, each step consisting of two categories of therapies, namely basal and additional. There are three pharmacotherapy plans for the long-term management of childhood bronchial asthma depending on the patient's age: under 2 years old (babies), 2–5 years old (infants), and 6–15 years old (school children) (Tables 5-8).

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal therapy | As needed | LTRA and/or DSCG | ICS (medium dose) | ICS (high dose) possibly add LTRA |

| Additional therapy | LTRA and/or DSCG | ICS (low dose) |

LTRA LABA (p.o. or adhesive skin patch) |

LABA (p.o. or adhesive skin patch) Theophylline (maintain at 5–10 mg/mL in blood concentration) should be considered |

- LABA is discontinued when good control level is achieved. LABA (p.o.) is defined as the drugs prescribed as twice a day. Theophylline is not used for patients under 6 months of age. Theophylline is not recommended for patients with history of convulsion. Prescription of theophylline for patients with fever should be with caution. Strongly recommend that uncontrollable patients with step 3 or step 4 management strategy be referred to experts in treating severe childhood asthma. DSCG, disodium cromoglycate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal therapy | SABA as needed | LTRA and/or DSCG and/or ICS (low dose) | ICS (medium dose) |

ICS (high dose) + (possibly add one or more of the following drugs) LTRA theophylline LABA or SFC |

| Additional therapy | LTRA and/or DSCG |

LTRA LABA or SFC theophylline (consider) |

Consider the following increase ICS/SFC to higher doses or p.o. steroid |

- LABA is discontinued when good control level is achieved. When SFC is started, oral and percutaneous LABA should be discontinued. Addition of SFC to ICS is acceptable; however, total dose of steroid is limited within the dose of basal therapy. SFC should be used for patients 5 years or more of age. Uncontrollable patients with step 3 management strategy should be referred to experts in treating severe childhood asthma. As an additional therapy at step 4, an increase of ICS/SFC to higher doses or p.o. steroid therapy or long-term admission management should be considered. Patients should be controlled under an expert in severe childhood asthma treatment. DSCG, disodium cromoglycate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SFC, salmeterol/fluticazone combined drug.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal therapy | SABA as needed | ICS (low dose) and/or LTRA and/or DSCG | ICS (medium dose) |

ICS (high dose) + (possibly add one or more of the following drugs) LTRA theophylline LABA or SFC |

| Additional therapy | LTRA and/or DSCG | Theophylline (consider) |

LTRA theophylline LABA or SFC |

Consider the following: increase ICS/SFC to higher doses or p.o. steroid |

- LABA is discontinued when good control level is achieved. When SFC is started, oral and percutaneous LABA should be discontinued. Addition of SFC to ICS is acceptable; however, total steroid dose is limited within the dose of basal therapy. It is recommended that uncontrollable patients with step 3 management strategy be referred to experts in treating severe childhood asthma. As an additional therapy at step 4, an increase of ICS/SFC to higher doses or p.o. steroid therapy or long-term admission management should be considered. Patients should be controlled under an expert in severe childhood asthma treatment. DSCG, disodium cromoglycate; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SFC, salmeterol/fluticazone combined drug.

| Manufacture of drug | Low dose (mcg) | Medium dose (mcg) | High dose (mcg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone | ∼100 | ∼200 | ∼400 |

| Beclomethasone | ∼100 | ∼200 | ∼400 |

| Ciclesonide | ∼100 | ∼200 | ∼400 |

| Budesonide | ∼200 | ∼400 | ∼800 |

| Budesonide inhalation solution | ∼250 | ∼500 | ∼1000 |

- High-doses of inhaled corticosteroid are preferable to use under the control of medical doctors with adequate experience in the management of childhood asthma.

Anti-inflammatory drugs are the primary drugs used for the long-term management of childhood asthma. Among them are inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), disodium cromoglycate (DSCG), long-acting β-agonist (LABA), and theophylline, of which ICS and LTRA are the principal drugs. JPGL2012 advises that an identical dose of ICS should be administered in each treatment step regardless of the age group. And low, medium and high doses of ICS are to be applied, respectively, to mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent cases.

Treatment of intermittent asthma (Step 1)

Patients should be treated with short-acting β-agonist as the need arises in asthma exacerbation. No regular medication with controller drugs is necessary. When symptoms continue and/or respiratory functions are unstable, long-term treatment with LTRA or DSCG may be needed. A step-up in treatment should be considered if a well-controlled level is not attained.

Treatment of mild persistent asthma (Step 2)

Basal therapy for step 2 is a low dose of ICS, LTRA and/or DSCG for the age groups of 2–5 and 6–15 years old. For the 2–5-year age group, LTRA is the first choice of these three drugs. For the under-2-years age group, ICS is not a basal drug but an additional drug when control level is unsatisfactory. Theophylline is an additional drug only for the age group of 6–15 years old.

Treatment of moderate persistent asthma (Step 3)

Basal therapy for step 3 should be done with a medium dose of ICS for all age groups of children. LTRA and/or LABA can be used as additional drugs when control level is unsatisfactory. ICS can be altered to an ICS+LABA combination formula for patients over 5 years old. Theophylline is another additional therapy for the age groups of 2–5 and 6–15 years old. Theophylline, however, should be used with caution for the age group of 2–5 years.

Treatment of severe persistent asthma (Step 4)

For patients at the severity level of step 4, a high dose of ICS should be used in combination with LABA, LTRA and/or theophylline as basal therapy for the age groups of 2–5 years and 6–15 years old. An ICS+LABA combination formula instead of ICS alone can be used as a basal drug for patients over 5 years old. For the under-2-years age group, a high dose of ICS is used in combination with LTRA as basal therapy. LABA is an additional drug and theophylline should be used with caution for infant patients under 2 years of age.

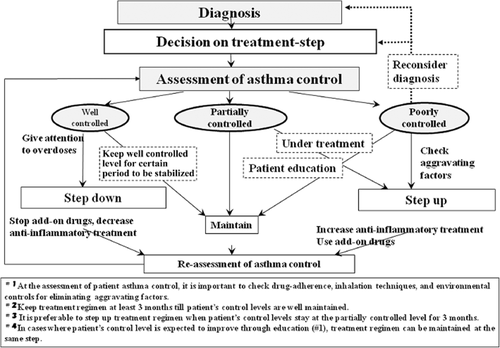

Asthma-management strategy based on control levels

Control levels are categorized into three grades: well-controlled, partially controlled, and poorly controlled levels. Each level is characterized by presence or absence of the following four indices: subtle asthma symptoms, apparent exacerbation, poor activities, and frequent use of β-2 agonist as rescue treatment (Table 9). Respiratory function indices, such as PEF and flow-volume curve, are useful if available. Treatment step can go up or down, approximately every 3 months, according to the patient's asthma control level. Points to consider then: whether or not drugs are taken as instructed, how well or badly environmental risk factors are managed, and other personal risks (Fig. 1).

| Component of control | Classification of asthma control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-controlled | Partially controlled | Poorly controlled | |

| Mild symptoms | None |

≧1/month ≦1/week |

≧1/week |

| Apparent symptoms | None | None | ≧1/month |

| Interference with normal activity | None | None | ≧1/month |

| SABA use for symptom control | None |

≧1/month ≦1/week |

≧1/week |

- Control levels are evaluated by conditions during the last 4 weeks. Mild symptoms indicate transient cough and/or wheezing induced by exercise, laughing and crying. Also included are short periods of coughing at the time of awakening and during sleep. Apparent symptoms indicate continuous coughing and wheezing with dyspnea and chest tightness. >80% of predicted/personal best in PEF and/or forced expiratory volume in 1 s. 0%~<20% of circadian changes in PEF, and <12% of FEV increase by β-2 agonist inhalation are preferable as well-controlled conditions. At the time of assessment, hospital admission due to severe exacerbation, use of oral glucocorticosteroid for symptom control, and seasonal exacerbation in the last 12 months should be considered. PEF, peak expiratory flow; SABA, short-acting β-agonist.

Strategy for long-term management of asthma.

JPGL2012 proposes a strategy for a clinician to maintain the patient on the well-controlled, or complete, level for a long time, help the patient keep a high QOL, and prevent airway remodeling as much as possible.

Well-controlled (complete) level

Well-controlled patients have no apparent asthma exacerbation, including wheezing and dyspnea, nor limitation of exercise or activities in daily life. Nor do they present signs and symptoms that suggest airway hyper-responsiveness, such as transient coughs, wheezing and/or slight dyspnea, even for a short period. They have no need to inhale β-2 agonist as rescue medication. Asthma symptom scores on both asthma condition evaluation charts, the Japanese Pediatric Asthma Control Program and the Childhood Asthma Control test, are full scores. Daily variations in PEF are less than 20% and/or keep the score at over 80% of the patient's best score. FEV1 is over 80% of the expected score and/or improvement after inhalation of β-2 agonist is less than 12%.

The set of conditions as above indicates that an adequate management status is attained. It is important to keep these conditions for as long as possible. A step-down might be considered when the level of this condition is maintained for more than 3 months without other risk factors, such as an episode of severe seasonal or periodic exacerbations.

Partially (fairly well) controlled level

Partially (fairly well) controlled patients infrequently have only subtle asthma symptoms, such as transient coughs, wheezing and/or slight dyspnea for a limited period when they exercise, have a big laugh or cry, and wake up in the morning; and pharmacotherapy is maintained at the present level. These patients' asthma symptoms are indeed controlled fairly well, but it is still unsatisfactory in pursuit of complete asthma control. A step-up in the management might be considered if the level cannot be improved within 3 months, during which patients are adequately educated about pharmacotherapy, including a re-instruction in inhalation techniques, and about enlightening procedures to keep their environment free of risk factors. Diagnosis and other complications also need to be checked.

Poorly controlled level

Poorly controlled patients frequently (once or more per week) have subtle asthma symptoms, such as transient coughs, wheezing and/or slight dyspnea for a short period, and often (once or more per month) have an apparent asthma exacerbation. These patients have difficulties in daily life and need frequently (once or more per week) to use β-2 agonist as rescue medication. Their management and treatment level are not adequate. Diagnosis and evaluation of asthma severity should be re-considered. Education regarding pharmacotherapy, including re-instruction of inhalation techniques, should be done, and intervention of environmental controls is necessary. Step-up of pharmacotherapy should be considered.

Infantile asthma (patients younger than 2 years of age)

Children younger than 2 years of age who have experienced wheezing more than three times on separate occasions are diagnosed as having infantile asthma. Wheezing may or may not be associated with a respiratory infection. In some cases, the diagnosis may be difficult to make because children of this age group often have wheezing associated with respiratory infection. The reason why we diagnose some infants as having infantile asthma by somewhat ill-defined criteria is that they should be treated and managed adequately so that they can enjoy good QOL from as early a stage as possible.

Patients with infantile asthma have special characteristics, not only in their anatomy but also in their pathophysiology. The airway caliber is narrow and lung flexibility and contractility is less than in older children. Hyper-secretion of mucus, and limited breathing movements due to a horizontally oriented diaphragm could easily cause airflow limitation, which induces a rapid exacerbation of asthma symptoms. The disease may become a chronic condition after its establishment in infants in this age group. Moreover, they cannot subjectively complain of respiratory failure, and so symptoms must be observed only objectively. There is therefore a requirement that an early diagnosis must be made and intervention should be started accordingly for patients of this age group.

Asthma during adolescence

There are three major problems of asthma in the period from adolescence to young adulthood: (i) patients show less willingness to adhere to long-term pharmacotherapy; (ii) they increasingly become dependent on β-2 agonist; and (iii) they lose interest in the environmental control associated with exacerbation risk factors against asthma. As a result, it is often the case that airway remodeling progresses and the mortality rate from asthma increases. Disturbances in lifestyle due to psychological stress that is related to friendships, schoolwork, or employment might contribute to poorer compliance with the doctor's advice.

The male-to-female ratio of asthma patients is 1.5:1 before adolescence, which decreases and comes close to 1:1 during this period and reverses at around 25 years of age. In severe cases, an obstructive pattern in flow-volume curve tends to be present and airway hyper-responsiveness persists during the symptom-free period, because of the progress in airway remodeling. Patients having frequent exacerbation in their adolescence possibly carry the symptoms over into their adulthood. It has been reported that obesity has a close relation to asthma, especially in female patients. Menstruation may be associated with asthma exacerbation. It is important to improve treatment compliance on the part of patients in this age group. It may be difficult, but sustained education and enlightening activities on the patients' behalf must be done with suitable explanations of asthma and individual treatment plans. Physicians also need to establish a good partnership with their patients.

Check-points for clinicians treating patients with adolescent asthma are as follows: monitor the patient to keep regular visits to the clinic; pay attention to lapses in adherence to medication use; monitor abuses of β-2 agonist; clarify the transition of care from pediatrics to internal medicine; re-evaluate the use or disuse of ICS; and maintain a good relationship with patients by providing sufficient information on available drugs and medication plans.

Inhalation and accessory devices

Pharmacotherapy using inhalation devices and accessories is the mainstay for the long-term treatment and management of asthma as well as for rescue therapy. It is essential for a clinician to know what constitutes an adequate selection of inhalation devices and accessories for patients in each of the different age groups. Have technical instructions ready that are patient-friendly and/or caregiver-friendly.

Inhalation techniques should be regularly checked using actual devices in front of doctors or other health professionals.

Education and enlightening activities

In the management of childhood asthma, how well a patient adheres to the treatment protocol contributes most to the success or failure in accomplishing a good control level. Knowledge and good understanding of the pathophysiology of bronchial asthma, anti-asthma medications and exacerbating factors help reinforce good adherence and compliance on the patient's part. Explanations according to the developmental stage of the child patient should be made in easily understandable words. Model structures, various figures, graphs and illustrations regarding asthma are useful for better understanding. Education and enlightenment is intended not only for the patient him/herself but also all members of the family, especially their main caregivers. The goal of therapy has to be shared with the patient, family members and all medical and co-medical staff. Therefore, it is critical to establish good relationships between doctors and the patient's family members.

Self-monitoring and action plans for the management of asthma through the behavioral approach can be made available. Several questionnaires can be utilized to improve the QOL of patients and family members.28-30

Exercise-induced asthma and other activities

Although the pathophysiology of exercise-induced asthma (EIA) has not been clarified very well, it is proposed that asthma (EIA) may result from increased osmotic pressure in bronchial epithelium caused by heat and water loss accompanied by hyperventilation, which is in response to hard persistent exercise, especially under the conditions of dry and cool air. It often occurs in patients with severe persistent or uncontrolled asthma. It is important for a clinician and a caregiver to be well aware of the characteristics of EIA and have a sufficient knowledge to manage it, because activities of children are often restricted at school, in the nursery or at home. A fundamental strategy against EIA is to keep a well-controlled level in daily life by using sufficient pharmacological treatment and avoidance of exacerbation factors. In order to prevent EIA, warm-ups are needed before exercise. Preventive use of medication is also available.31-33

Conclusion

A new edition of the JPGL, namely the JPGL2012, was introduced, which reflects recent progresses in asthma treatment and management for children. The most important change from the previous version is to introduce an asthma-management strategy based on the patient's asthma control level, the concept of which was introduced for the first time in the GINA 2006 guidelines. In this version of the JPGL, “well-controlled level” is set as completely controlled status without subtle symptoms, such as even a short period of wheezing and/or cough. It is important to maintain a well-controlled state for a long enough period, which in turn affords good QOL and may ultimately result in remission and cure. Anti-inflammatory medicines, that is, ICS (including ICS+LABA combination and LTRA) are the most important drugs for the treatment of chronic airway inflammation initiated with an immediate type of allergic reaction.

A long-term management with anti-inflammatory controller drugs, elimination of airborne antigens, such as house dust mites, animal products and molds from the patients' living environment, and enlightenment and education about bronchial asthma are the three fundamental factors for the treatment and management of childhood asthma.