Evaluation of resting state gamma power as a response marker in schizophrenia

Abstract

Aims

An abnormal activity in the electroencephalography (EEG) gamma band (>30 Hz) has been demonstrated in schizophrenia and this has been suggested to be reflecting a deficit in the development and maturation of the basic cognitive functions of attention, working memory and sensory processing. Hypothesizing gamma oscillatory activity as a potential EEG biomarker to antipsychotic response in schizophrenia, the present study aimed at measuring baseline spontaneous gamma activity in schizophrenia patients, and evaluating its response to antipsychotic treatment over 8 weeks.

Methods

Fifteen drug-free/naïve patients were recruited, compared at baseline with 15 age-, sex- and education-matched healthy controls, and were followed up for 8 weeks' treatment on antipsychotics. Resting state EEG waves were recorded using high (192-channel) resolution EEG at admission, 4 weeks and 8 weeks. Spectral power was calculated using fast Fourier transformation, Hanning window. The power was averaged region-wise over nine regions in three frequency ranges (30–50 Hz, 50–70 Hz, 70–100 Hz).

Results

Patients and controls differed significantly at intake in terms of left temporal and parietal high (70–100 Hz) gamma power. Consequently, no significant differences were seen over the course of antipsychotic treatment on gamma spectral power in any of the regions.

Conclusions

Lack of significant effect of treatment on gamma power suggests that these gamma oscillations may be trait markers in schizophrenia.

The etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia, a major mental disorder, remains unclear despite intensive research and advances in the field of mental health. Biomarker research enhances neurobiological understanding of the illness, leading to better evidence-based biological therapies. However, among various biomarkers studied in schizophrenia research, few of them are monitored and predicted together.1 Quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG or EEG), especially resting-state EEG, may offer some promise in this regard as they can serve as cost-effective clinical tests that predict treatment response. Moreover, given differential treatment response to antipsychotics, there is a recent quest for a potential EEG biomarker to antipsychotic response in schizophrenia.2 Such biomarkers have also been proposed to be useful in early-phase clinical studies for schizophrenia.3

Neuronal gamma-band (>30 Hz) oscillations, which can be recorded in most cortical and sub-cortical areas, represent a fundamental process that serves as an elementary operator of brain function and communication.4 Activity in gamma frequency represents both local and long-range synchronization.5 Gamma oscillations have been linked with an array of distinct cognitive and sensory functions: perception, attention, memory, consciousness and synaptic plasticity.5 They reflect a deficit in the development and maturation of these basic neural functions.6 Expectedly, schizophrenia patients, with abnormalities in these functions, have consistently demonstrated an aberrant activity in the gamma frequency band.7 Further, studies have associated an alteration in gamma band activity with positive and negative symptoms' severity in schizophrenia.8-11

Studies on gamma activity in schizophrenia have mostly investigated either steady state or evoked responses and those studying spontaneous or resting state activity are relatively less common. Recently, spontaneous gamma activity has gained additional importance as it has been shown to determine or influence task-related measures.12 Although, generally reports on EEG high-frequency oscillations in schizophrenia are heterogeneous as to reduced or increased gamma activity,13 findings from studies investigating spontaneous activity consistently show increased gamma oscillatory power in schizophrenia patients.12, 14, 15

Increased resting-state gamma oscillatory activity reported in untreated schizophrenia patients12, 15 is consistent with the glutaminergic hypothesis that stems from the result that N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists mimic schizophrenia symptoms by disinhibiting pyramidal cells and increasing excitability.16, 17 GABAergic interneuron abnormalities found in schizophrenia have also been associated with the pathophysiology and abnormal gamma activity seen in the disorder.18 Moreover, modulation of GABAergic transmission by dopamine/D4 receptor function as well has been suggested to regulate gamma oscillations and related cognitive processes.19

Various animal studies have shown that antipsychotics, both first- and second-generation agents, have been shown to vary spontaneous high-frequency, especially gamma oscillatory activity.20-22 Few studies specifically have investigated antipsychotic treatment effects on human gamma band activity. Hong et al. (2004)23 found that although schizophrenia patients as a group did not significantly differ from controls, patients taking new-generation antipsychotics had significantly enhanced gamma synchronization compared to patients taking conventional antipsychotics. No study has investigated the effect of antipsychotics on dense array gamma oscillations in medication-free schizophrenia patients prospectively at specific time-points.

We hypothesized that baseline resting gamma oscillations would be higher in schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls and specifically that there would be reduction in the activity over the prospective natural course of antipsychotic treatment. We investigated resting-state gamma spectral power at two response stages – early (4 weeks) and late (8 weeks) – from treatment initiation compared from baseline (untreated stage).

Methods

The study was conducted at the KS Mani Centre for Cognitive and Neurosciences, Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), Ranchi. It was approved by the Institute's ethics committee.

Participants

All the participants gave informed consent. Sixteen drug-naïve or drug-free (at least 4 weeks for oral and 12 weeks for depot medications) right-handed patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia as per ICD 10 DCR24 were recruited using purposive sampling from amongst the patients admitted at the Institute. We excluded those who had: (i) a history of any other comorbid psychiatric disorder; (ii) a major neurological or medical illness, including head injury and epilepsy; (iii) drug or alcohol dependence, except nicotine or caffeine use; and (iv) those who had received electroconvulsive therapy in the past 6 months. One patient dropped out because of a diagnostic revision and the study was completed with 15 patients. The healthy control group included 15 right-handed age-matched subjects, recruited from the hospital staff and community living in the vicinity of CIP.

Assessment

Relevant sociodemographic data were collected from the patients upon admission. The subjects were rated on the Sidedness Bias Schedule25 to assess handedness, and on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)26 to quantify their psychopathology and to follow them up through the study. Healthy controls were screened with the General Health Questionnaire 12;27 only those with scores < 3 were included.

EEG recording

Subjects fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent an EEG recording between 09.00 and 12.00 h on the day of their admission. Spontaneous resting EEG was recorded for 3 min during each recording while the patient sat relaxed on a recliner inside a light- and sound-attenuated room with eyes closed. The EEG was recorded using a custom-made scalp cap with 192 Ag-AgCl electrodes (Electro-Cap International, Eaton, Ohio, USA) in accordance with the international 10-5 system. Eye movement potentials were monitored using right and left electro-occulogram channels. Electrode impedance was kept < 5 kΩ. EEG was filtered (time constant, 0.1 s; high-frequency filter, 120 Hz; notch filter, 50 Hz) and digitized (sampling rate, 512 Hz; 16 bits) using Neurofax EEG-1100K (Nihon-Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). At the end of 4 weeks and 8 weeks of treatment, the EEG was recorded under similar circumstances.

Spectral analysis

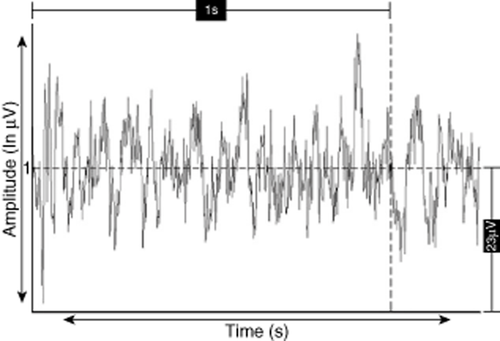

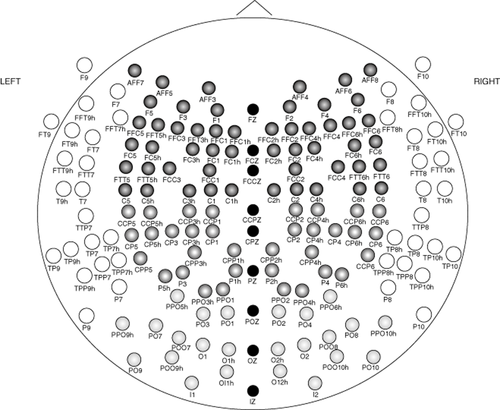

Artifacts were visually identified. Eye movement/blink, body movement and muscle tension artifacts were visually detected and epochs containing them were discarded, and a 30-s artifact-free EEG data clip was visually selected from each of the recordings. The selected epochs were recomputed with common average reference (Fig. 1 shows waveforms at Cz electrode in a recording of a patient with schizophrenia). The raw EEG signals of all the subjects in both phases were filtered using a linear phase 300th order band pass finite impulse response (FIR) digital filter. Spectral power was calculated in micro-Volts with fast Fourier transformation, Hanning window using Welch's averaged periodogram method. The power was averaged region-wise over right and left frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital and central regions (nine regions, Fig. 2). Gamma spectral power was estimated in three frequency bands: the low- (30–50 Hz, gamma 1) and high-gamma (51–70 Hz, gamma 2; and 71–100 Hz, gamma 3) bands. MATLAB-8 (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) was used for spectral analysis.

Waveforms at Cz electrode in a patient with schizophrenia.

Placement of electrodes according to the International 10-5 system. Various shades show the region-wise distribution of electrodes used for spectral power computation.  , Frontal;

, Frontal;  , Temporal;

, Temporal;  , Parietal;

, Parietal;  , Occipital;

, Occipital;  , Midline.

, Midline.

Statistical analysis

Demographic differences between patients and healthy controls for continuous and categorical variables were computed using independent samples t-test and Fisher's exact test, respectively. Comparison of spectral power between the groups was done using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Repeated measures anova was done to compare psychopathology scores over time. Freidman's test was used to compare spectral power over time. Spearman's correlation was subsequently performed between changes in psychopathology and gamma measures; also with type and dose of antipsychotics. For controlling multiple comparisons, variables showing statistical significance at P < 0.05 were reviewed at P < 0.0125 (for comparing PANSS scores [0.05/4]) and P < 0.00185 (for gamma spectral power comparisons and correlations (0.05/27 [i.e. region [9]*band [3] combinations]) by applying the Bonferroni correction. Statistical analysis was done using spss 16.0 (spss, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The patient and the control groups were comparable in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. Eleven of the 15 patients were diagnosed with paranoid type; seven had a positive history of family psychiatric illness. Four patients were drug-naïve, and the rest were drug-free. Mean duration of illness was 55.13 months. At the end of 4 weeks, the patients were on a mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dose of 516.62 ± 208.61 mg, and after 8 weeks, the mean equivalent dose was 496.26 ± 242.35 mg. At 4 weeks, nine patients were on olanzapine, four were on risperidone and two on haloperidol. At 8 weeks, nine were on olanzapine, three were on risperidone, two were on quetiapine and one was on haloperidol. Table 2 shows the comparison of PANSS scores over time. We found significant reduction in the total and all the sub-scores at week 4 and week 8 compared to baseline; also between weeks 4 and 8 (even after controlling for multiple comparisons).

| Variables | Patients | Controls |

t/χ2 (Fisher's exact) d.f. = 1,28 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(N = 15) Mean ± SD/ n (n%) |

(N = 15) Mean ± SD/ n (n%) |

||||

| Age (years) | 28.87 ± 6.81 | 29.33 ± 5.85 | 0.201 | NS | |

| Sex | Male | 12 (80) | 12 (80) | 0.00 | NS |

| Female | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | |||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 1.067 | NS |

| Married | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | |||

| Religion | Hindu | 12 (80) | 11 (73.3) | 1.710 | NS |

| Non-Hindu | 3 (20) | 4 (26.7) | |||

| Education | Primary or less | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0.00 | NS |

| Secondary | 7 (46.7) | 7 (46.7) | |||

| Intermediate | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | |||

| Graduate or more | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | |||

| Family monthly income | <5000 INR | 6 (40) | 3 (20) | 3.333 | NS |

| 5000–10 000 INR | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | |||

| >10 000 INR | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | |||

| Habitat | Rural | 10 (66.7) | 3 (20) | 13.912 | <0.01 |

| Urban | 5 (33.3) | 12 (80) | |||

| Diagnosis | F20.0 | 11 (73.3) | |||

| F20.3 | 3 (20) | ||||

| F20.9 | 1 (6.7) | ||||

| Family psychiatric history | Affective disorder | 3 (20) | |||

| Non-affective psychosis | 4 (26.7) | ||||

| None | 8 (53.3) | ||||

| Drug status | Naïve | 4 (26.7) | |||

| Free | 11 (73.3) | ||||

- INR, Indi an rupee; NS, not significant.

| PANSS score | Week 0 (1) | Week 4 (2) | Week 8 (3) | F | Post-hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 27.13 ± 7.46 | 15.67 ± 5.39 | 10.60 ± 3.37 | 47.11** | 1 > 2 > 3* |

| Negative | 21.60 ± 10.30 | 12.80 ± 5.40 | 10.07 ± 4.07 | 13.77* | 1 > 2 > 3* |

| General psychopathology | 35.60 ± 8.26 | 22.87 ± 6.32 | 19.40 ± 5.88 | 39.95** | 1 > 2 > 3* |

| Total | 83.87 ± 15.90 | 51.80 ± 13.36 | 39.33 ± 9.96 | 66.24** | 1 > 2 > 3* |

- *P < 0.0125; **P < 0.0025.

- PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Table 3 shows the significant difference (at P < 0.05) between the patient and control groups at baseline on spectral power in gamma 1 of the right frontal and left occipital regions; gamma 2 of the left frontal region; and gamma 3 of the right and left parietal, left temporal and central regions. After controlling for multiple corrections, significance difference was restricted to the left parietal and temporal gamma 3 spectral power. Spectral power in these bands/regions was higher in patients than controls (See Fig. S1 [supporting information] for comparison of topoplots showing spectral power in gamma 3 frequency band across representative sample of schizophrenia patient and healthy control groups at baseline).

| Regions | Z | P | Significant difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma 1 (30–50 Hz) | |||

| Right frontal | 2.012 | 0.044 | NS |

| Left frontal | 0.145 | 0.885 | NS |

| Right parietal | 0.684 | 0.494 | NS |

| Left parietal | 1.514 | 0.130 | NS |

| Right temporal | 1.431 | 0.152 | NS |

| Left temporal | 0.726 | 0.468 | NS |

| Right occipital | 0.228 | 0.820 | NS |

| Left occipital | 2.261 | 0.024 | NS |

| Central | 0.394 | 0.694 | NS |

| Gamma 2 (50–70 Hz) | |||

| Right frontal | 0.021 | 0.983 | NS |

| Left frontal | 2.012 | 0.044 | NS |

| Right parietal | 0.933 | 0.351 | NS |

| Left parietal | 0.353 | 0.724 | NS |

| Right temporal | 1.887 | 0.059 | NS |

| Left temporal | 1.804 | 0.071 | NS |

| Right occipital | 0.518 | 0.604 | NS |

| Left occipital | 1.431 | 0.152 | NS |

| Central | 0.104 | 0.917 | NS |

| Gamma 3 (70–100 Hz) | |||

| Right frontal | 1.182 | 0.237 | NS |

| Left frontal | 1.224 | 0.221 | NS |

| Right parietal | 2.426 | 0.015 | NS |

| Left parietal | 3.505 | 0.000** | Patients > controls |

| Right temporal | 1.804 | 0.071 | NS |

| Left temporal | 3.256 | 0.001* | Patients > controls |

| Right occipital | 1.804 | 0.071 | NS |

| Left occipital | 0.270 | 0.787 | NS |

| Central | 2.302 | 0.021 | NS |

- *P < 0.00185. **P < 0.00037.

- NS, not significant.

Table 4 shows the comparison of spectral power values in the three gamma bands across baseline and treatment stages: acute and late. Consequent significant (P < 0.05) persistent reduction in spectral power values was seen on gamma 1 and 2 bands in the left occipital region. Right frontal gamma 1 power showed significant (P < 0.05) reduction at week 4 compared to baseline but showed significant (P < 0.05) increase at week 8 compared to week 4. However, no significant differences over time were found in spectral power of any of three bands in the nine regions when correction for multiple comparisons was applied.

| Region | Gamma band | Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | ||||||

| Right frontal | 1 | 2.40 | 1.33 | 2.27 | 10.133 | 0.006 |

| 2 | 2.20 | 1.80 | 2.00 | 1.200 | 0.549 | |

| 3 | 2.27 | 1.67 | 2.07 | 2.800 | 0.247 | |

| Left frontal | 1 | 2.20 | 1.67 | 2.13 | 2.533 | 0.282 |

| 2 | 2.40 | 1.93 | 1.67 | 4.133 | 0.127 | |

| 3 | 2.33 | 1.80 | 1.87 | 2.533 | 0.282 | |

| Right parietal | 1 | 2.00 | 1.87 | 2.13 | 0.533 | 0.766 |

| 2 | 2.00 | 2.27 | 1.73 | 2.133 | 0.344 | |

| 3 | 2.20 | 1.73 | 2.07 | 1.733 | 0.420 | |

| Left parietal | 1 | 2.00 | 1.73 | 2.27 | 2.13 | 0.344 |

| 2 | 1.93 | 1.73 | 2.33 | 2.800 | 0.247 | |

| 3 | 2.40 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 4.800 | 0.091 | |

| Right temporal | 1 | 2.40 | 1.73 | 1.87 | 3.733 | 0.155 |

| 2 | 2.47 | 1.73 | 1.80 | 4.933 | 0.085 | |

| 3 | 2.40 | 1.87 | 1.73 | 3.733 | 0.155 | |

| Left temporal | 1 | 2.27 | 1.53 | 2.20 | 4.933 | 0.085 |

| 2 | 2.47 | 1.80 | 1.73 | 4.933 | 0.085 | |

| 3 | 2.47 | 1.73 | 1.80 | 4.933 | 0.085 | |

| Right occipital | 1 | 2.40 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 4.800 | 0.091 |

| 2 | 2.40 | 1.80 | 1.80 | 3.600 | 0.165 | |

| 3 | 2.33 | 1.93 | 1.73 | 2.800 | 0.247 | |

| Left occipital | 1 | 2.53 | 1.80 | 1.67 | 6.533 | 0.038 |

| 2 | 2.47 | 2.00 | 1.53 | 6.533 | 0.038 | |

| 3 | 2.27 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 1.600 | 0.449 | |

| Central | 1 | 2.27 | 1.67 | 2.07 | 2.800 | 0.247 |

| 2 | 2.20 | 1.93 | 1.87 | 0.933 | 0.627 | |

| 3 | 2.13 | 1.87 | 2.00 | 0.533 | 0.766 | |

No significant correlations were found between types of antipsychotics used, their doses with change in PANSS scores or gamma spectral measures. No significant correlation was seen between change in PANSS scores at week 4 and week 8 and corresponding changes in gamma spectral measures.

Discussion

Increased resting state gamma power in schizophrenia

The present study results, as hypothesized, show that resting state spectral power in various gamma sub-frequency bands across various regions was increased in the schizophrenia group compared to controls. Although earlier studies investigating gamma response to cognitive/perceptual tasks report deficits in gamma oscillations, recent studies point to the possibility that resting state gamma oscillations may differ from the one associated with task-related cognitive processing. Kikuchi et al.28 had found significantly elevated resting-state gamma-band power over frontal electrodes in medication-naïve, first-episode schizophrenia patients. Spencer10 reported a similar finding: significantly increased ∼40 Hz baseline source power in chronic patients with schizophrenia. Unmedicated schizophrenia patients, both familial and sporadic, and especially those with a higher number of developmental anomalies, are reported to have increased gamma spectral power.15, 29 This verifies that, at baseline, gamma oscillatory activity and hence glutaminergic neurotransmission is deranged in schizophrenia patients. Adequate drug-free intervals before EEG recording in our patients, use of the averaged reference30, 31 for estimation of gamma spectral power, and the high spatial and temporal resolution offered by 192-channel EEG adds credibility to our findings.

Frontal regions in 30–70-Hz gamma bands and parieto-temporal regions in 70–100-Hz bands showed significantly higher values; significance, however, was limited to 70–100-Hz frequency bands, particularly in the left parietal and temporal regions, when multiple-comparisons correction was applied. This finding supports the proposal that high-gamma activity is distinct in terms of temporal, spatial and functional specialization from low-gamma activity.32

Effect of treatment on psychopathology and gamma power

Results on the effect of treatment show significant reductions in the psychopathology scores at the early stage that further reduced at the late stage. This suggests that response to treatment was significantly good. Treatment in the schizophrenia group, however, did not result in significant differences in spectral power values, in any of the scalp sites, at follow-up recordings compared to baseline findings. While studying treatment effects in neuroleptic-naïve schizophrenia patients, Kikuchi et al.33 inferred that the gamma global field synchronization is unaffected by treatment and considered it as a trait marker for schizophrenia. In another study, Takahashi et al.34 also found no antipsychotic treatment effect on gamma spectral power in drug-naïve schizophrenia patients. In line with these findings, lack of significant effect of treatment on gamma spectral power suggests that these gamma oscillations are trait markers in schizophrenia. Moreover, family studies have found resting state gamma spectral activity to be possible trait markers for schizophrenia.14

Studies measuring treatment effects on gamma oscillations in schizophrenia have included patients on both conventional and newer antipsychotics.33, 34 As introduced, some studies23 have shown that patients taking new-generation and conventional antipsychotics differ in their effect on gamma synchronization. Our study results did not show significant correlation between types of antipsychotic, dosage and change in psychopathology or gamma power. Animal models have studied the effect of individual antipsychotics on gamma power. Sustained and significant decreases in ongoing gamma power were found during chronic administration of haloperidol or clozapine.21, 22 No study in humans, however, has studied the differing effect of individual antipsychotics on gamma oscillations in schizophrenia. Such studies would require larger samples.

Regional specificity in treatment effects

Regional specificity in treatment effects was limited to results when multiple-comparisons correction was not used. Although concrete conclusions could not be drawn, we discuss these results as there can be certain scientific implications.

Schizophrenia has been related to enhanced attention to relevant signals and a lack of inhibition of irrelevant signals.35, 36 It has been suggested that signals from the occipital region represent irrelevant neuronal signals and those from other regions are relevant.37, 38 Now, treatment with antipsychotics in the present study could significantly reduce and sustain reduction of occipital gamma spectral power and not elsewhere (P < 0.05). This suggests that antipsychotic agents target and facilitate inhibition of irrelevant neuronal signals – occipital gamma oscillations – in schizophrenia patients.

Gamma spectral power in the right frontal areas, although reduced significantly at early treatment stage (4 weeks), failed to endure this reduction; rather, it increased significantly at the late stage compared with the early stage. We suggest that possible mechanisms for this finding might be a positive modulation at NMDA receptors during the early treatment phase and a reverse modulation later. The acute effect might be due to an indirect effect of dopaminergic and serotonergic antagonism of antipsychotics on NMDA receptors, while the late effects might be a result of overpowering of neurodevelopmentally modulated abnormal synaptic neurotransmission.

Strengths and limitations

Our study suffered from certain limitations, such as a small sample size (N = 15) and smaller representations of the female sex (n = 3). However, repeated measures over 8 weeks have improved the reliability of the study results, and they lend credibility to our findings. We ensured uniformity amongst the subjects in terms of handedness, and also achieved a high degree of comparability between patients and control group in terms of age and sex. Past studies have reported changes in gamma over the follow-up period, ranging from 3 to 6 weeks. Our study ensured all subjects were tested at the same time, so as to more confidently delineate temporal evolution of gamma waves. As mentioned previously, a very dense array of 192 electrodes provided our findings with improved spatial resolution.

To explore any potential direct pharmacological effects of medications on gamma power (e.g., effects that could be observed when antipsychotics are administered to healthy controls) we correlated type of antipsychotic and their doses with change in PANSS scores and gamma spectral power. No significant correlations were found. Although this lack of correlation suggests that individual types of antipsychotics may not have any direct effects on the spectral power changes, we might not be able to draw any definitive conclusions.

Moreover, the issue of multiple comparisons, which is inherent to brain-imaging studies, is a constraint. When controlling for multi-testing, variables showing significant difference over treatment course, without correction, were found to lose significance. While it controls false positives, this kind of correction has been argued to increase the probability of producing false negatives that reduce the statistical power of the study.

Another limitation was in the graphical (topo-imaging) representation of results. Individual waveforms and spectral maps of individual subjects presented in the manuscript do not represent the overall results.

Conclusion

This report provides evidence for a lack of change in spontaneous neuronal integrating function, assessed in terms of gamma spectral power, in schizophrenia with treatment. Lack of significant effect of treatment on gamma power suggests that these gamma oscillations are trait markers in schizophrenia. The findings, thus, have wide-ranging implications in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

We do not have any conflict of interest. We have not received any financial aid for conducting this study.