Efficacy of an expanded preoperative survey during perioperative care to identify illicit substance use in teenagers and adolescents

Section Editor: Dean Kurth

Abstract

Background

As illicit substance use can present several perioperative concerns, effective means to identify such practices are necessary to ensure patient safety. Identification of illicit substance use in pediatric patients may be problematic as screening may rely on parental reporting.

Aims

The current study compares answers regarding use of illicit substances between a survey completed by the patient and the preoperative survey completed by parents or guardians.

Methods

The study included patients presenting for surgery at Nationwide Children's Hospital, ranging in age from 12 to 21 years. After consent, patients completed a survey of six drop-down questions using an iPad. The six questions involved the patient's history of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, vaping, and opioid use. The results were compared to the answers obtained from the parents during a preoperative phone call.

Results

The study cohort included surveys from 250 patients with a median age of 16 years. Survey data showed a statistically higher reporting of substance use or abuse from the patient study survey in comparison to the routine parental preoperative survey. Alcohol report rates were highest with 69 (27.6%) patients reporting use compared to only 5 parental reports (2%). There was a similar discrepancy in reported rates of vaping use (40 patient reports, 16.0% vs. 11 parental reports, 4.4%) and illicit substance use including marijuana (52 patient reports, 20.8% vs. 11 parental reports, 4.4%). Reported rates of tobacco use were lowest among the survey responses with 12 patient reports (4.8%) and 5 parental reports (2.0%).

Conclusions

Identifying illicit substance and tobacco use via a phone survey of parents is inaccurate and does not allow for proper identification of use of these substances in patients ≤21 years of age presenting for surgery. An anonymous 2-min survey completed by the patient more correctly identifies these issues.

1 INTRODUCTION

The annual prevalence of illicit substance use throughout the United States in 8th, 10th, and 12th graders has continued increasing after a significant decline during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Additionally, while substance use overall decreased in 8th, 10th, and 12th graders during the pandemic, drug overdose deaths nearly doubled in 2022 in adolescents ages 12–17.2 Illicit substance use often starts during adolescence with reports suggesting that more than 80% of drug users began using during adolescence. Data collected in 2022 from middle and high schoolers in the United States indicated that 3.3% and 14.1% of middle and high schoolers, respectively, use e-cigarettes.3 In addition to the immediate impact on morbidity and mortality related to acute toxicity, acute and chronic use of illicit substances can impact perioperative care, impacting the effect of anesthetic agents on end-organ function, and potentially increasing perioperative morbidity.4, 5 While it is clear that illicit substance use is an increasingly prevalent concern throughout the United States and many parts of the world, there are limited data on how best to identify it during the perioperative period.

At our children's hospital, preoperative information regarding health issues, previous surgeries, nil per os times, and other preoperative concerns is generally obtained from the parents. Given these practices, it is also common for screening for illicit substance use to rely primarily on parental reporting during the preoperative evaluation. Additionally, even if information is obtained directly from the patient, this questioning may be influenced if it is performed in the presence of parents. The current study compares answers regarding the history of illicit substance use between a survey completed by the patient on the day of surgery and the preoperative survey completed by parents or guardians during the pre-admission testing phone call.

2 METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nationwide Children's Hospital (STUDY00002306) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05353036). Patients, ranging in age from 12 to 21 years, was selected from the preoperative holding area of the main operating room. Surveys were collecting from patients during the summer months for prescheduled surgical procedures occurring at Nationwide Children's Hospital main campus typically during the hours of 7 a.m.–4 p.m. on weekdays. Due to the time constraint of urgent or emergent cases, inclusion of these patients in the study cohort was not deemed feasible. As the survey was available for administration only in English, non-English speaking patients were not eligible for inclusion. Likewise, due to the intricacy of the survey and the need to be able to use an iPad, patients with cognitive impairment or significant learning disabilities were also ineligible. All other pediatric patients presenting for anesthetic events were eligible for the survey. Consent was obtained from a parent/guardian for those less than 18 years of age or the patient if they were more than 18 years old. Assent was obtained from patients who were 12–17 years of age. The participants were made aware that the survey was anonymous, so that their parents and the treating physicians would not have access to the data collected. The number of participants was tracked via REDCap and patients who denied participation were tallied separately to obtain a survey response rates. As this was a preliminary descriptive study, with the only analysis being based on demographic data, a formal power analysis for other outcomes was not performed.

The patient completed the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) survey on an iPad without parental oversight. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Nationwide Children's Hospital.6, 7 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing an interface for validated data capture; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for data downloads to common statistical packages; and, procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

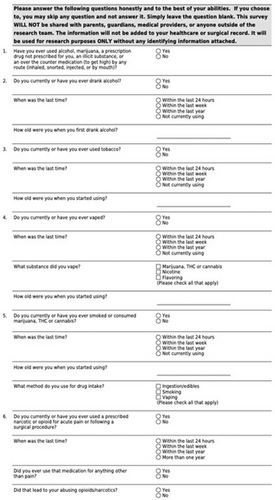

The survey consisted of drop-down questions regarding illicit substance use in general and then specifically including alcohol, tobacco, vaping, marijuana, and narcotics (Figure 1). Using the drop-down survey, patients were asked to indicate “yes” or “no” to the use of various substances. If a participant selected “yes” to using any of the illicit substances, additional questions populated the survey asking about the age they started using the substance, and the last time they used the substance. Each participant could select any number of different substances, and drop-down questions would populate for each one. For vaping, an additional question asked about the substance they vaped with the options of nicotine, flavoring, and marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabis. For marijuana consumption, a drop-down question asked about the method of drug intake with the options of smoking, vaping, and ingestion/edibles. The narcotics question began by asking the participant if they had ever received narcotics, with drop-down questions asking about use of narcotics.

After survey completion, demographic data were collected from the patient's EPIC profile. The data collected included gender, race, ethnicity, age, and zip code. Each patient's EPIC profile at Nationwide Children's Hospital has a section completed by the parent during a preoperative screening phone call by our pre-admission testing team of registered nurses. During this phone interview, parents are asked yes or no questions about their child's history of illicit substance, tobacco, and alcohol use. There are specific yes or no questions asked as to whether their child smokes, vapes or uses alcohol, smokeless tobacco or drugs. No specific follow-up questions are provided in the script for the preoperative interview if there is an affirmative response to any of the questions. Further questioning and investigation is left to the attending anesthesiologist on the day of surgery. The data from the parental survey obtained during the preoperative screening phone call was collected from the participant's profile. These data were connected to the participant's REDCap survey responses.

Data analysis was conducted using Python (Python Software Foundation). Chi-squared testing was used to compare the REDCap patient survey response to the EPIC parental survey data for each substance and to compare categorical demographic data to reports of substance use.

3 RESULTS

A total of 346 patients were initially approached regarding participation to accrue a final study cohort of 250 patients, resulting in an accrual rate of 72.3%. The final study cohort of 250 patients ranged in age from 12 to 21 years (mean age 15.8 ± 2.3 years) (Table 1). Self-identified race of the study cohort included White/Hispanic or Latino (n = 187, 74.8%), Black or African American (n = 37, 14.8%), Asian (n = 11, 4.4%), American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 1, 0.4%), more than one race (n = 12, 4.8%), or unknown/not reported (n = 2, 0.8%). The median income was $51 636 (IQR $39 627, $66930.20) based on zip code data collected from the electronic medical record (data missing from four patients).

| Number of patients | 250 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12–21 (15.8 ± 2.3) | |

| Male/female | 109/141 (43.6%–56.4%). | |

| Self-identified race | White/Hispanic | 187 |

| Black or African American | 37 | |

| Asian | 11 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | |

| More than one race | 12 | |

| Unknown/not reported | 2 | |

- Note: Data are listed as the mean ± SD or the number.

Of the 250 patients who completed the survey, 59 of 248 (23.8%) answered yes when asked “Have you ever used alcohol, marijuana, a prescription drug not prescribed to you, an illicit substance, or an over-the-counter medication to get high by any route (inhaled, snorted, injected or by mouth)?”. Two of the 250 participants did not answer the initial survey question. This contrasts to parental responses, where only 11 of 250 (4.4%) answered yes when asked about drug or illicit substance use and 5 (2%) reported alcohol use. Of the four categories, 47 participants (19%) reported using more than one substance.

In the follow-up questions on the patient survey, which asked specifically about which substances were used, more than the 59 who had originally answered yes to the broad question about alcohol or illicit substance use, answered yes to any one of the specific questions of the four substances. Of the 250 participants, 69 (27.6%) reported using alcohol, 51 (20.4%) reported using marijuana, 40 (16%) reported vaping, and 12 (4.8%) reported using tobacco. Only two reported opioid misuse while only one reported opioid abuse (n = 3, 1.2%).

Alcohol use was reported by the largest number of patients. More than one-fourth (27.6%) of the survey respondents reported drinking alcohol at some point in their lives (Table 2). This was substantially more than the parental response which responded yes to alcohol use in only five patients (2%, p < .001) (Table 3). Of the 69 participants who self-reported drinking alcohol, 15 (21.7%) stated they were not currently drinking alcohol, 2 (2.9%) reported drinking alcohol within the past 24 h, 11 (15.9%) reported drinking alcohol within the past week, and 41 (59.4%) had consumed alcohol within the last year. The median age for initiation of alcohol consumption was 16 years (IQR 14, 17 years).

| Question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you currently or have you ever drank alcohol? | |

| No response recorded | 1 (0.4) |

| No | 180 (72) |

| Yes | 69 (27.6) |

| When was the last time? | |

| Not currently using | 15 |

| Within the last 24 h | 2 |

| Within the last week | 11 |

| Within the last year | 41 |

| How old were you when you first drank alcohol? (median, IQR in years) | 16 (14, 17) |

- Note: Data are listed as the number (%) or median and IQR in years for age.

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

| Overall (%) | Patient (%) | Parents (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||

| No response recorded | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 425 (85.2) | 180 (72.3) | 245 (98.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | 74 (14.8) | 69 (27.6) | 5 (2.0) | |

| Drug use | ||||

| No | 437 (87.4) | 198 (79.2) | 239 (95.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 63 (12.6) | 52 (20.8) | 11 (4.4) | |

| Vaping | ||||

| No response recorded | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 448 (89.8) | 209 (83.9) | 239 (95.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 51 (10.2) | 40 (16.0) | 11 (4.4) | |

| Tobacco | ||||

| No response recorded | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 482 (96.6) | 237 (95.2) | 245 (98.0) | .136 |

| Yes | 17 (3.4) | 12 (4.8) | 5 (2.0) | |

Marijuana use was the second most commonly used substance as reported by participants with 51 patients (20.5%) reporting use (Table 4). No specific question is currently included in our hospital's preoperative screening phone call regarding marijuana, cannabis, or THC use. The most common method of intake was smoking (n = 42), followed by vaping (n = 27), and ingestion (n = 24). Nineteen participants reported marijuana use within the last year while only six reported using within the last 24 h and 16 within the last week. Ten patients reported that they were not currently using. The median age to begin marijuana use was 16 years (IQR 14, 17 years).

| Question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you currently or have you ever smoked or consumed marijuana, THC or cannabis? | |

| No response recorded | 1 (0.4) |

| No | 198 (79.2) |

| Yes | 51 (20.4) |

| When was the last time? | |

| Not currently using | 10 |

| Within the last 24 h | 6 |

| Within the last week | 16 |

| Within the last year | 19 |

| Method or route for drug intakea | |

| Smoking | 42 |

| Vaping | 27 |

| Ingestion of edible | 24 |

| How old were you when you started using? (median, IQR in years) | 16 (14, 17) |

- Note: Data are listed as the number (%) or median with IQR for age.

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

- a Method or route of intake equals more than number responding yes (n = 51) as there may be more than one route of ingestion per respondent.

Vaping was third among responses from participants with 40 patients or 16.0% reporting its use (Table 5). This was less than the parental response which stated yes to vaping in 11 patients (4.4%, p < .001) (Table 3). Vaping exceeded those who reported using tobacco (12 patients or 4.8%). Of the 40 participants who responded yes to the question about vaping, 11 patients were not currently using while 10 patients had vaped in the last 24 h, 12 in the last week, and 7 in the last year. Nicotine was the most popular vaping substance followed by marijuana, THC, or cannabis. The median age to being vaping was 15.5 years (IQR 14, 16 years).

| Question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you currently or have you ever vaped? | |

| No response recorded | 1 (0.4) |

| No | 209 (83.6) |

| Yes | 40 (16.0) |

| When was the last time? | |

| Not currently using | 11 |

| Within the last 24 h | 10 |

| Within the last week | 12 |

| Within the last year | 7 |

| Substance vapeda | |

| Marijuana, THC or cannabis | 17 |

| Nicotine | 32 |

| Flavoring | 15 |

| How old were you when you started vaping? (median, IQR in years) | 15.5 (14, 16) |

- Note: Data are listed as the number (%) or median and IQR in years for age.

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

- a The substance vaped equals more than the number responding yes (n = 40) as more than one substance was vaped.

Tobacco use was reported in a minority of the survey participants (12 or 4.8%) (Table 6). This was not different from the parental response which stated yes to smoking in 5 patients (2%, p = NS) (Table 3). Five of the 12 patients that reported a history of tobacco use, reported that they were not currently smoking tobacco. Of the remaining 7, 3 reported tobacco use in the past 24 h, 2 within the last week, and 2 within the last year. The median age of starting tobacco use was 15 years (IQR 14, 15.5 years).

| Question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you currently or have you ever used tobacco? | |

| No response recorded | 1 (0.4) |

| No | 237 (94.8) |

| Yes | 12 (4.8) |

| When was the last time? | |

| Not currently using | 5 |

| Within the last 24 h | 3 |

| Within the last week | 2 |

| Within the last year | 2 |

| How old were you when you started using? (median, IQR in years) | 15 (14, 15.5) |

- Note: Data are listed as the number (%) or median age and IQR for age.

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Positive reports of opioid misuse or abuse were lowest of any of the responses from the patient surveys with two patients reporting opioid misuse and one patient reporting opioid abuse (Table 7). There was no specific question on parental surveys to address opioid abuse outside of a broad question on drug use, in which 11 (4.4%) parents reported drug use (Table 3). Thirty-five (14%) patients reported receiving opioids at some point following a surgical procedure or for acute pain. Thirteen reported that they were not currently using opioids while 3 reported using within the last 24 h, 3 within the last week, and 15 within the last year. When asked if they ever used the opioids for anything other than pain (opioid misuse), 2 said yes while one reported that this resulted in further opioid abuse.

| Question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you currently or have you ever used a prescribed opioid for acute pain? | |

| No | 215 (86.0) |

| Yes | 35 (14.0) |

| When was the last time? | |

| Not currently using | 13 |

| Within the last 24 h | 3 |

| Within the last week | 3 |

| Within the last year | 15 |

| Did you ever use that medication for anything other than pain? | |

| No | 33 |

| Yes | 2 |

| Did that lead to your abusing opioids/narcotics? | |

| No | 34 |

| Yes | 1 |

- Note: Data are listed as the number (%).

When considering the entire cohort and the impact of demographic variability on illicit substance and tobacco use, there was no significant difference in illicit substance or tobacco use based on gender, race, or income. Patients who were ≥ 16 years of age were more likely to drink alcohol, vape, and smoke or consume marijuana.

4 DISCUSSION

Despite the importance of identifying the use and abuse of illicit substances prior to anesthetic care, there is no standard approach or survey used during the preoperative screening process. Currently at Nationwide Children's Hospital, a list of questions is asked of the parent or guardian during the pre-admission testing phone call prior to the surgical procedure. This survey asks simple yes or no questions regarding the child's history of illicit substance, tobacco, and alcohol use. There are no specific questions about opioid misuse, abuse, or drug addiction. There are specific yes or no questions asked as to whether their child smokes, vapes or uses alcohol, smokeless tobacco, and drugs. No specific follow-up questions are provided in the script for the preoperative interview if there is an affirmative response to any of the questions. Further questioning and investigation is left to the attending anesthesiologist on the day or surgery.

We hypothesized that there would be a difference between surveys completed by parents and their children as parents might not be aware of their child's habits and open communication may not always be present in families. Furthermore, questioning adolescents regarding substance abuse in front of their parents may not be revealing due to concerns of parental sanctions regarding such practices. To avoid these limiting factors in the current study, patients completed the survey without parental oversight and they were assured that data would be kept anonymous. In our study, we noted a higher incidence rate of substance use reported by survey participants when compared to parents for everything except tobacco. Although the incidence of tobacco use reported by the patients was more than twice that reported by the parents (4.8% vs. 2%), the relatively low rate of tobacco use may have precluded the ability to achieve statistical significance.

An unexpected finding was that more survey participants reported consuming alcohol when asked about alcohol specifically than when asked broadly about substance use or abuse, suggesting that the participants who completed the survey do not consider alcohol a drug or illicit substance despite the fact that they were below the legal age for alcohol consumption. In fact, alcohol was the most common substance used by the patients completing the survey, followed by marijuana, vaping, tobacco, and opioids, respectively.

The results from this survey confirm the original study hypothesis that substance use or abuse is underreported by parents when compared to patients and that a more accurate reflection of the true incidence of substance use/abuse and the actual substances being used can be obtained by asking the patient. To avoid biasing responses, we suggest that survey responses should be collected anonymously without parental input to ensure as accurate a response as possible. With significant differences in reporting rates, a new survey method likely needs to be implemented to accurately identify at risk patients. Identification of illicit substance use is not only imperative to prevent perioperative complications, but may allow for interventions and behavioral strategies to decrease substance abuse following the surgical intervention.8-10 Studies in various clinical scenarios has shown that early intervention programs may improve long term outcomes related to substance use for adolescents in a variety of studies.8 These interventions are effective for various substances including alcohol, marijuana, and other substances. In addition to decreasing substance abuse, additional benefits have included a reduction in other behaviors including peer aggression and risk-taking.8 Similarly, studies from the adult population have specifically demonstrated that the preoperative environment is an effective environment to offer information on tobacco cessation as patients may be willing to consider lifestyle changes especially when facing significant challenges related to an upcoming surgical intervention.9, 10 There are also more specific unanswered questions which are specifically relevant to the anesthesia practitioners regarding how these findings should impact our practice regarding the anesthetic at hand, should an elective surgical procedure be postponed if recent use is identified, are there day-of-surgery interventions that can be used to limit subsequent substance abuse, is there a process in place for outpatient referrals for long-term counseling and interventions, or are immediate changes in postoperative opioid prescriptions/use required. These questions remain unanswered and are outside the scope of the current study. However, given their impact on perioperative care and future outcomes, they may provide the basis for future investigations.

As a secondary objective of the study, we attempted to define if there were any demographic findings which pointed to a higher incidence of illicit substance use. Of the demographic data collected, we noted only that those who were more than 16 years of age had a higher likelihood of using illicit substances. In line with recommendations for the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the American Academy of Pediatrics, these data support the recommendations that all pediatric patients above the age of 12 years should be screened for drug abuse with the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) model whenever they are receiving medical care, as no demographic data indicates a greater risk of substance use outside of age.11 The National Institute on Drug Abuse offers both the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) and Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and other Drugs (BSTAD) as validated screening tools for adolescences ranging in age from 12 to 17 years.11, 12

Recent data collected throughout the COVID-19 pandemic indicated a decrease in alcohol, marijuana, and vaping use in adolescents in 8th, 10th, and 12th grade; however, it is unknown whether this is a true decrease or related to adolescents completing the survey at home, rather than at school, with less privacy from parental oversight.13 Even the National Institute on Drug Abuse's director was unclear as to what caused the decrease in substance use, although it was noted that factors such as “drug availability, family involvement, differences in peer pressure” may have played a role.13 While this study cannot contrast trend data, it does show a clear indication that substance use in children and adolescents is still a major issue in our communities that needs to be addressed within the healthcare network. An extension of this study could look at the association and trends of the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to pediatric substance use when considered within the lens of accessibility and social seclusion caused by isolation and remote learning.

One limitation of this study is that data were only collecting during the summer months. It is possible that these data would differ if collected throughout other times of the year as it is possible that substance use may vary during the schoolyear compared to the summer months. Additionally, the surveys were collected from patients undergoing prescheduled surgical procedures. Due to the rapid nature of urgent or emergent cases, inclusion of these patients in the study cohort was not deemed feasible. The survey asked “yes” or “no” questions regarding substance use and did not assess the frequency of such use although the proximity of use (when did you last use?) was assessed. Although this study took place at only one hospital in Ohio, it is clear that substance misuse and abuse is a prevalent problem within the pediatric and adolescent population today.1-3 However, the rates of substance abuse and the agents involved may vary from region to region within the United States and worldwide. Future studies may be required to further define geographic and demographic differences in the substance use and abuse. However, we believe that these problems have a significant impact on all geographic and demographic groups.

One of the main primary concerns regarding preoperative substance abuse that we could not address with the current study was its impact on postoperative opioid use or abuse. Patients with a history of preoperative substance abuse may have a higher incidence of postoperative opioid misuse. A future initiative could be to look at the association of preoperative substance use and its impact on these concerns. Such a study would require a prolonged prospective design with an evaluation of patients with prolonged opioid use or repeated prescript refills. Additionally, the potential impact of substance use on perioperative outcomes was not assessed. Given the infrequency of perioperative complications, especially in a relatively health cohort of patients ranging in age from 12 to 21 years, a much large study cohort would be needed.

Through this study, we sought to identify a more effective method of accurately identifying substance use in children. The current survey, completed anonymously by the patient, resulted in a higher incidence of reported use of illicit substances than that reported by parents. The survey was easily completed by the patient without interfering with the workflow of the busy preoperative area of the inpatient surgical unit of a tertiary care children's hospital. Our hospital provides anesthetic care for approximately 38 000 patients a year in 40 anesthetizing locations. Given this was only a survey study, there was no means to verify the responses provided by the patient through drug screening. Additionally, the study was conducted during the summer months in our operating rooms. We are not aware of data that specifically addresses the incidence or pattern or substance abuse during the summer versus the school year. Screening tools such as this survey may not only be useful in identifying illicit substance use and thereby reducing its impact on anesthetic care, but may also serve as a platform for interventions to counsel patients.14, 15

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.