Leveraging normative power in co-production to redress power imbalances

Abstract

In this article, we explore how less dominant actors, service users in our case, utilize different types of power to influence more dominant professional groups during processes of co-production. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with 48 service users involved in healthcare improvement research, we illuminate the crucial role of normative power during processes of co-production. In contrast to extant co-production literature, which largely focuses on structural or resource power, we show how normative power is created by service users to leverage influence over more dominant actors. We highlight the relationship between structural, resource, and normative power during processes of co-production, extending understandings of the dynamic nature of co-production and generating implications for public involvement policy and practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of co-production has been a key topic of research and policy over the last two decades, as we seek to understand how to maximize the important role played by service users in public service planning, production, and delivery (Beresford, 2019; Chauhan et al., 2023; Haug, 2024; Nederhand & Van Meerkerk, 2018). Defined as a process through which citizens “play an active role in producing public goods and services of consequence to them” (Ostrom, 1996, p. 1073), co-production can be understood as “an umbrella concept that captures a wide variety of activities that can occur in any phase of the public service cycle and in which state actors and lay actors work together to produce benefits” (Nabatchi et al., 2017, p. 769). However, a resounding message from extant research is that true co-production is rarely identified, with service user involvement often described as “tokenistic” (Steen et al., 2018; Verschuere et al., 2012).

Tokenistic involvement is often ascribed to the unequal power status that exists between service users and more dominant professional groups who may be reluctant to involve other parties, privileging their own experiences and knowledge over that of service users (Steen et al., 2018; Voorberg et al., 2015). The tacit knowledge held by service users poses a significant challenge to the knowledge and expertise gained by dominant professional groups through formal education and certification (Gaventa, 1993; Gaventa & Cornwall, 2008; Oborn et al., 2019). Established professional groups derive power from knowledge gained through formal education, meaning they are vested in maintaining the status quo (Abbott, 1988; Gaventa, 1993), and may dismiss the tacit knowledge of less powerful groups, such as service users, and marginalize their involvement in co-production. As such, it can be challenging to integrate service users into existing multi-professional teams where there may be power imbalances between team members (Martin & Finn, 2011).

Policy initiatives attempting to redress the power imbalances within processes of co-production often rely on interventions to increase the resource power (i.e., expertise, knowledge or networks) (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2008; Lukes, 2005), or structural power (i.e., determining the inclusion or exclusion of topics for discussion) (Lukes, 2005; McCabe et al., 2021) of service users, for example, by engaging them through formal employment (Beresford, 2019; Bevir et al., 2019; Chauhan et al., 2023). This focus on resource and structural power is arguably because the majority of research exploring power imbalances in processes of co-production has focused specifically on the different resources or structures available to dominant professional groups, in contrast to service users, who may subsequently struggle to be genuinely involved in co-production (Amann & Sleigh, 2021; Contandriopoulos, 2004; Williams et al., 2020). For example, Amann and Sleigh (2021) examined challenges in involving vulnerable groups in co-production and highlighted that, researchers, the more powerful groups in co-production, possess decision-making power, that is, resource power, compared to the vulnerable public involvement members. In short, notwithstanding a handful of notable exceptions (Chauhan et al., 2023; McCabe et al., 2021), extant research has paid relatively little attention to how service users can agentically leverage power to wield influence over more dominant professional groups during processes of co-production.

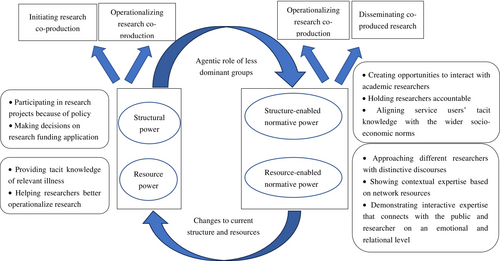

In this article, we draw on Luke's three dimensions of power (i.e., resource power, structural power, and normative power), to ask: how can service users utilize different types of power to influence more dominant professional groups during processes of co-production? Drawing insights from 48 semi-structured interviews with service users involved in the co-production of healthcare improvement research, we illuminate the important, yet largely obscured, role of normative power during processes of co-production. We make three contributions to the co-production literature. First, we extend research examining the agentic role of less dominant actors, in our case service users, in leveraging power over more dominant actors during the process of co-production. Second, we illuminate the various ways that normative power can be created by less dominant actors during co-production. Specifically, we identify two distinct forms of agentically constructed power leveraged by service users: structure-enabled normative power and resource-enabled normative power. Finally, we present a model to highlight the cyclical relationship between structural, resource, and normative power during processes of co-production, highlighting its dynamic nature.

2 POWER IN PROCESSES OF CO-PRODUCTION

Existing understandings of co-production are underpinned by the democratic principle of public involvement and contribution of service users, highlighting the importance of their expertise and experiential knowledge (Lehoux et al., 2012; Martin, 2008; Oborn et al., 2019). Service users commonly accumulate tacit knowledge through personal experience in dealing with illnesses of their own or the people they care for, or through self-education such as learning and socializing with professionals (Degeling et al., 2015; Oborn et al., 2019). The tacit knowledge of service users is distinct from, but complementary to, the codified and objective knowledge held by medical professionals (Martin, 2008; Oborn et al., 2019).

However, it is equally as highlighted that the “complexity and richness” of service user knowledge is often not recognized by more powerful professional groups, leading to tokenistic involvement as dominant professionals attempt to retain control over decision-making (Abbott, 1988; Green & Johns, 2019; Lehoux et al., 2012). For example, involvement may be controlled by professionals selecting the “right” type of service users, those who are articulate and educated and have certain desirable skills (El Enany et al., 2013). Dominant professional groups might also keep service users at arm's length and only involve them for certain activities (Contandriopoulos, 2004; Croft et al., 2016), further exacerbating the unequal power dynamics characterizing the relationship between service users and professionals.

Nevertheless, it would be reductive to assume that all co-production research characterizes the relationship between service users and dominant professionals as a one-way power dynamic. It is often acknowledged that less powerful groups “retain the capacity to act in ways that counter the dominant power” of professional groups (Prior, 2009, p. 32). For example, Farr (2018) offered a panoramic view of power in co-production, highlighting the agency of less powerful groups in co-production to ensure more equal relations through processes such as reflective practice and continuous communication. Although not focusing on co-production specifically, Huising (2014) similarly explored how less dominant actors such as managers and lab coordinators involved in research and development leveraged increased influence over previously dominant research specialists during a planned change.

Another reason service users may be increasingly able to leverage power over more dominant actors is related to the changing characteristics of professional work, which is linked to the changing demographics of clients (Huising, 2023; Mukherjee & Thomas, 2023). That is, well-informed and educated clients do not simply comply with notions of professional expertise based on an abstract knowledge system, but increasingly value relational expertise (i.e., whether professionals are able to relate to, and interact with, clients) and contextual expertise (i.e., understandings of the broader organizational system in which they are situated) (Abbott, 1988; Huising, 2023; Mukherjee & Thomas, 2023). This creates an opportunity for previously less powerful, non-professional actors to exert influence over the provision of professional work by previously dominant actors.

Therefore, increasingly, research focuses more on how service users may leverage different types of power during processes of co-production (Amann & Sleigh, 2021; Chauhan et al., 2023; Farr, 2018; McCabe et al., 2021). Much of this work builds on Lukes' definition of power as identifiable acts, discourse or relationship between people, delineated along three dimensions: structural power, resource power, and normative power (Lukes, 2005).

Structural power relates to dominant actors shaping or controlling the inclusion and exclusion of certain issues in the co-production agenda (McCabe et al., 2021), and can be exerted through “manipulating decision-making rules or exploiting existing rules” (Lukes, 2005, p. 27). This may involve limiting less dominant actors' access to key pieces of information, or putting them in a disadvantageous position by setting rules and regulations so they are unable to fully participate in the decision-making process (Croft et al., 2016; McCabe et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2007). Structural power can also be wielded by appointing decision-makers from their own professional group who are likely to agree with the dominant perspective, and alternative voices can be minimized (O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016). Resource power is the mechanism of “controlling decision-making by prevailing in debates” by “mobilizing superior resources, such as knowledge, personal charisma or formal authority” (Lukes, 2005, p. 27). Resource power is characterized by expertise, knowledge, network, formal authority, or any other superior resources used by one actor to influence another (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2008; McCabe et al., 2021).

Normative power involves “shaping the controlled's interests” (Lukes, 2005, p. 27), so that less dominant actors accept “their role and the existing order of things” (Lukes, 2005, p. 11). As the “most effective” and “supreme” form of power (Lukes, 2005, pp. 27, 28), normative power is “exerted by shaping the controlled party's desires, beliefs and perceptions in ways contrary to their interests” (Hayward & Lukes, 2008, p. 6). By employing normative power, dominant actors might be able to manipulate less powerful actors to make them believe that the interests of dominant actors are their own interests (Farr, 2018). Through normative power, the more dominant group influences others to abide by the norms of usual practice, retaining the status quo so that their interests and jurisdiction is protected, such as in the case of collaboration between academic researchers and practitioners (McCabe et al., 2021).

Normative power is primarily exercised through socialization and education (Culley & Angelique, 2011; Lukes, 2005; McCabe et al., 2021; O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016). Through these processes, dominant actors can propagate “truths” and prevail meaning over less dominant actors. For example, normative power can be leveraged directly by proposing certain problems and providing solutions, which could be achieved through “thought leadership,” publishing research reports, training, and advertising (O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016). Normative power can also be exercised indirectly through discourse, language, and symbols to construct meaning and shape preferences (Culley & Angelique, 2011; O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016). For example, Culley and Angelique (2011, p. 413) showed that dominant actors, nuclear advocates in this case, employed the rhetoric of “nukespeak,”—“the use of metaphor, euphemism or technical jargon to portray nuclear technology in a neutral or positive way,” to thwart public participation in governmental dispute related to global climate change. Normative power can also be leveraged through phrases and terms that align with the wider socioeconomic norms. For example, the language McKinsey uses such as “talent,” “war” was in line with the wider norms of post-war Europe in the diffusion of McKinsey ideas, giving McKinsey legitimacy among clients in this context (O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016).

Notable co-production research has previously utilized Lukes' (2005) three-dimensional framework of power to explore the impact of power dynamics between users and professional groups on the outcome of co-production. For example, McCabe et al. (2021) explored the effects of the three types of power on co-production between academic researchers and practitioners. They found that structural and normative power are insufficient to ensure effective knowledge co-production, highlighting the role of resource power and the facilitating role played by academic researchers. Chauhan et al. (2023) showed that service users were able to utilize normative power by embedding expertise that did not challenge the dominant groups' control and knowledge, leading to enhanced co-production. This suggests that a possible relationship exists between normative power and expertise-based resource power. However, research is yet to explore how less dominant groups agentically create and subsequently leverage normative power to facilitate meaningful co-production.

Therefore, this article asks the question of how service users utilize different types of power to influence more dominant professional groups during processes of co-production. To do so, we draw from an empirical case of co-producing healthcare improvement research by service users and academic researchers, exploring the role of normative power to redress power imbalances.

3 METHODS

3.1 Empirical context

Our exploration of processes of co-production focuses on service users working with academic researchers in healthcare improvement research, linked to one of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded translational research centers in the United Kingdom. Our setting provides an ideal context to explore how less dominant groups attempt to leverage power over more dominant groups during processes of co-production for two reasons. First, NIHR has an established history of promoting the co-production of research between academic researchers and service users in healthcare improvement research (NIHR, 2016). Involvement of service users is seen as increasingly important in the co-production of healthcare improvement research through the full cycle of research activities: research initiation (proposal development and funding application), research operationalization and dissemination (Cashman et al., 2008; Degeling et al., 2015). Second, our setting is characterized by the power dynamics between service users and a more dominant professional group, in this case academic researchers, who establish dominance through their codified, and expert knowledge gained through education, socialization, and research practices.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

In this article, we draw on 48 semi-structured interviews with service users and secondary analysis of NIHR documents related to public involvement (Table 1). The service users interviewed were involved in co-producing healthcare improvement research through an NIHR Research Centre. The interviews were carried out from April 2017 to November 2018, and participants were initially identified through one of the academic researchers in the center followed with a snow-balling technique. Ethical approval for the study was sought and granted before sending out the study invitation. Interviews lasted around 1 h and were transcribed verbatim. Interviewees were asked to describe their experiences in public involvement, how they became involved in research projects, and discuss how they worked together with academic researchers.

| Date published | Shortened name | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 25 February 2020 | NIHR guide to public involvement | NIHR: A brief guide to public involvement in funding applications |

| 5 April 2021 | NIHR notes for researchers | NIHR: Briefing notes for researchers—public involvement in NHS, health and social care research |

| 10 June 2022 | NIHR research governance guidelines | NIHR: Research governance guidelines |

| November 2019 | UK standards for public involvement | UK Standards for Public Involvement: Better public involvement for better health and social care research |

Our data analysis comprised the following two main steps. First, we derived informant-centric coding (first order codes) and identified the core activities described by each service user about how they interacted with researchers and navigated through different stages of research. We then theorized first order codes into more abstract second order codes, and aggregate dimensions (Table 2). For example, we identified how service users utilized resource-enabled normative power (aggregate dimension) to influence academic researchers, which they described as approaching different researchers with different discourses (second order codes). In the words of informants (first order codes), the observable actions are: service users learning how to deal with different academic researchers through various meetings and socialization events, service user learning to “speak academic speak” to engage academic researchers (Table 2). Through this process, we identified two main processes through which power was utilized by service users to leverage influence during co-productions of research: (1) structural power and structure-enabled normative power, and (2) resource power and resource-enabled normative power.

| Selected quotes | First-order code | Second-order code | Theoretical dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| In order for them (researchers) to get research funding that they would need to have public (user) involvement… it must be obvious to them by now that they won't get funding unless they make some effort to include service users to help them write the proposal or to scrutinize it or to provide input onto what service user interventions they might put in their proposal to make their research proposal more effective. (ID 20) | Required to have service users on research proposal for funding application | Participating in research projects because of policy |

Structural power |

We're asked sometimes to go and judge those projects. A lot of them are over-wordy…I expect there'd be something in there that tells me exactly what the point of this is in a general manner. (ID 42) Responses to these questions will be considered by the reviewers, research panels and boards (which increasingly include members of the public) and will influence funding decisions. (NIHR notes for researchers) |

Service users invited to assess the lay summary section of research proposal | Making decisions on research funding application | |

| There is only about 180 people going to that (conference)…researchers and managers and service users themselves. I'm going as a service user. I found it quite difficult to find someone to pay for me to go as a service user. So, I reached out, and they let me off the fee eventually…We need to improve how the NHS views, including researchers, service users, because if we can involve them more, then that interaction between the researcher or clinician or whoever and the individual members of the public that they're working with would be more appropriate, more effective. (ID 39) | Service users extending the interaction with academic researchers and arguing for more interaction | Creating opportunities to interact with researchers | Structure-enabled normative power |

I think their (service user) role is to make sure that public money is spent in the way that benefits the public, and not benefits the hospital or the clinicians or others…There needs to be some sort of public accountability, and Service users can provide that. (ID 20) …It's being able to stop things early on if they're going on a tangent that's not relevant to patients and what they want and need. So it's about considering what a patient and public perspective is and making sure that's what's presented in the public funds that are used to fund research. (ID 30) |

Service users hold researchers accountable and making sure the specific public fund is used appropriately | Holding researchers accountable in existing structures | |

| At the moment, researchers tend to want to get their names on citation lists don't they, and that's the end of it really…It is a legal requirement now that researchers have to publish their findings in some way or another that shows impact. (ID 39) | Service users utilizing the new requirement of the research world in terms of producing high impact research | Aligning service users' tacit knowledge with the wider socioeconomic norms | |

| As a researcher, unless you've got that condition you've no idea what it's like to go through the process, what it feels like, and how you were treated. That's what they're using my experience for. (ID 44) | Service users possessing knowledge of illness through experience | Providing tacit knowledge | Resource power |

| One of the big problems I've discovered with a lot of research projects I get involved in is recruitment. They can't get people…they can't get enough numbers to recruit. If they had involved the public more, they might have foreseen some of those problems. (ID 7) | Service users helping researchers with lay summaries or accessible language | Helping researchers to better operationalize research | |

| I think a lot of researchers they're in a very ivory tower environment…they're out of touch with what's real to people, so like those issues to do with parking and traveling and whose available when and whose going to be willing to do things. So I think people can, a PI person (service user) can offer practical advice, another point of view. (ID 23) | Service users helping researchers identify practical issues related to conducting research | ||

| It's about evaluating ideas. It's about coming up with new ideas…Thinking about other people's ideas, what they're trying to do and giving a critical analysis, not to be derogatory but to find the weak points. Why are you doing this? Why aren't you doing that? So it's giving a stimulus to other people's ideas. (ID 2) | Service users learning how to deal with different academic researchers and work in a way that researchers work | Approaching different researchers with distinctive discourses | Resource-enabled normative power |

| I feel that academics only think about academic output like getting stuff into journals. They don't think about maybe contacting community groups, women's magazines, (and) health magazines, these sorts of things that ordinary folk are going to read or see… we help them to see that it doesn't just disseminate in one direction only, toward other academics, doctors, healthcare professionals, but also to interested groups like the general public. (ID 7) | Service users can help researchers find venues to disseminate research findings through patient networks | Demonstrating contextual expertise based on network resources | |

| Last year we had one of our researchers bringing one of their service users to an event again to talk about their study and that, the impact from that was, the whole audience was engaged. (ID 4) | Patients are more likely to relate to service users | Demonstrating interactive expertise that connects with the public and researcher on an emotional and relational level | |

| I think you have to be quite eloquent; you have to be able to put your point across quite well, and I think you have to be quite patient in the sense that you're working with people who have been, quite often they've been doing their jobs for a long time and they think they know best. So you have to be patient in letting them say what they have to say and provide constructive criticism…I think that's quite important to have somebody who's good at having relationships with people. (ID 30) | Service users explored ways to build trust and relationship with academic researchers |

4 FINDINGS

Our findings indicated that during processes of co-production of research, structural and resource power were most important to initiate involvement. However, to sustain involvement throughout the co-production process, service users needed to generate and subsequently utilize normative power to influence academic researchers' beliefs and perceptions of user involvement. Generating different forms of normative power was reliant on agentic use of structure and resource, whereby service users actively utilized existing structures and resources to their advantage.

4.1 Structural power and structure-enabled normative power

Our findings illuminate how certain structures put in place by funding bodies or mandated by institutional policies can help initiate research co-production, that is, enabling service users to be involved in various research activities that would otherwise not fall under their remit.

NIHR has a standard application form used by all research programmes…One of the sections on the form asks applicants to describe how they have involved the public (service user) in the design and planning of their study as well as their plans for further involvement throughout the research, including plans for evaluating impact. (NIHR notes for researchers)

There's always a PI adviser (service user) on all these panels when they go for funding, and if the PI adviser (service user) says the user involvement is rubbish and marks it down, your vote is equal to anybody else's vote. So, I have the same vote as a health economist or the chair. (ID 20)

However, the mere presence of such structures might indicate tokenistic involvement. Researchers might “ignore” their questions about research projects and not take them on board or consider suggestions from service users. Although service users could be involved in meetings and given the opportunity to express their ideas, they might be “quietly dumped” if their views “put the back of the researcher up” (ID 22). To sustain involvement throughout the research co-production process, we found that service users in our case actively utilized various forms of structure to generate normative power to influence academic researchers' belief and perception of user involvement, which we call “structure-enabled normative power.”

…I was quite keen to get involved with [academic researcher name] and [academic researcher name] with one-to-one meetings. Because I became much better informed about the research process and some of the issues that they face as a result of that…to [be able to] do that sort of thinking and inform the clerk (academic researchers) about how it could be done better. (ID 19)

The steering committee meeting, in my experience, can be very good…The next time you meet they said, well, the last time you did raise the following points, and make the following suggestions, and we've managed to do this, and we haven't managed to do that because xyz, how do you feel about that? And this particular thing, we're still working on that, but it's going in the right direction now and we do find that such and such. (ID 39)

…one of the many criteria that universities are assessed on is increasingly looking at the impact of research. So, it's all very well you've done your study; hopefully you've got a good publication, but it's that next bit…researchers are probably not very good at disseminating findings…and we as service users, can definitely help research dissemination. (ID 17)

In sum, service users were able to utilize structures to generate normative power, which changed researchers' belief and perception of user involvement and facilitated meaningful co-production. Specifically, service users took the initiative to create opportunities to interact with researchers, hold researchers accountable in existing meetings, and align their tacit knowledge with the wider socioeconomic norms of the research world.

4.2 Resource power and resource-enabled normative power

If you're doing something about diabetes, have you consulted people who have diabetes? Because ultimately whatever you're going to do is going to influence people with that condition. It's important to engage with that group of people, and get their perspective and to validate, justify that the work that you're doing is benefiting them. (ID 4)

It (The research) was so full of technical terminology that I wouldn't understand with my O Levels. The thing has to become more user-friendly from a patient point of view…Service users can help with that, and make it more accessible (ID 21)

Sometimes it could be practical advice, rather than more intellectual advice or patient experience…I was asked to be involved in a study, where they were looking at Pyodermata and Rheumatoid Arthritis. They'd already set the study up, but they'd got nobody to participate in the study. So then they said “would you be involved and help us work out why we got such low take-up?,” and it's really easy for me to see why they had low take up. They had low take up because they were doing it in [place name], where there's no parking and it's really difficult to get to for patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. (ID 30)

Nevertheless, on multiple occasions, academic researchers tried to keep service users at arms' length and away from conducting research. Service users told us they found academics, who were established in the research world, tended to disregard the experiential and tacit knowledge of service users. In situations like this, service users utilized various resource to generate normative power to reshape the belief and perception of academic researchers on service users and influence the co-production process which we call “resource-enabled normative power.”

I've worked with the researchers now for a long time. I've been to meetings, conferences with quite a lot of them…I know the way they work, and I also know how best to put things. How I give feedback to one academic might be different to how I give feedback to another academic, because I know them and I know how they will respond, and I know what ticks their boxes. (ID 30)

I try to do it very gently…I have to say, “well, have we thought about doing it this way, someone else does it this way and it really works.” It's just my experience of how to put message across working with researchers. (ID 39)

You need to be able to read a paper and take something from it. So, you need some analytical skills, because otherwise, you're not going to be able to have a sensible discussion with academics. (ID 3)

I think the great value in having people like us involved is that we're often connected within communities, so we can be quite influential about getting the various messages out…researchers appreciate that we can disseminate much more broadly into the community, at all the various places in the community where the new research ought to reach. (ID 19)

I've spoken about my experiences at conferences, and people have said, how, of the whole conference, that was the one that really spoke to them the most….because of the great feedback from the audience, later that year, I was invited by [researcher] to join some members of the research team at a health event and give a presentation on service user involvement to a healthcare conference last year. (ID 30)

People would be more readily willing to join a trial if they were talking to somebody with a similar problem who was involved in the trial, rather than somebody, a medic or researcher somewhere that is doing it because it's his or her job. (ID 31)

If you've got to work with people then you've got to get trust, and it's about people being familiar with you, and chatting over coffee, and all that sort of thing…and now we're getting on to the actual work (co-producing research), because that's now starting to unfold. (ID 13)

To sum up, although resources are useful to initiate and operationalize research, our findings indicate that resource-enabled normative power is more effective in operationalizing and disseminating research. In particular, we found that service users classified different researchers and approached them with distinctive tacit resources to get their messages across, demonstrated their contextual expertise based on network resources, and showed their interactive expertise in relating to the public and researchers. Service users utilized these resources to change the belief and perceptions of researchers and therefore, were able to exert normative influence over researchers.

5 DISCUSSION

Our findings illustrated how service users can leverage different types of power, that is, structural power, resource power, and normative power, at different stages of the co-production process. As outlined in Figure 1, service users were able to utilize structural power when initiating co-production of research by participating in research projects, facilitated by policy and their decision-making involvement on potential funding applications. They were then able to leverage resource power through initiation and operationalization of the research by providing tacit knowledge in relation to relevant illnesses and related practical concerns. However, our most significant finding is that, in the latter stages of research (operationalizing research and disseminating co-produced research), normative power was created by less dominant actors through structures and resources, to influence more dominant groups. Our findings showed how service users utilized existing structures to generate structure-enabled normative power by creating opportunities to interact with academic researchers, holding academic researchers accountable during prearranged meetings (i.e., steering group meetings), and aligning service users' tacit knowledge with wider socioeconomic norms. Our findings also illuminated three ways to generate resource-enabled normative power through existing resources: approaching different researchers with distinctive discourses, showing contextual expertise based on network resources, and demonstrating interactive expertise that connects the public and researcher on an emotional and relational level.

Building on our findings, we make the following three contributions to the co-production literature. First, we illuminate an alternate perspective on the power dynamics between service users and more powerful professionals in co-production processes. Specifically, we extend understanding by illustrating how less dominant service users are able to leverage power over more dominant professional groups to engage in meaningful co-production. While previous research has often focused on the “dark side” of co-production (Steen et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2020), where service users are conceptualized as the controlled actor in the power relationship, with more dominant professionals controlling structures and resources (Amann & Sleigh, 2021; Glimmerveen et al., 2018), we challenge this characterization. As outlined in Figure 1, by highlighting the agentic role of less dominant groups, we showed how service users are able to create normative power based on existing structures and resources during the process of research co-production. In doing so, we align with a growing body of research illuminating the changing dynamics of professionalism and professional work in the modern day, due to increasingly well-informed and educated clients, increasing public scrutiny, and influence from multiple stakeholders such as managers, clients, and the public (Huising, 2023; Mukherjee & Thomas, 2023).

Second, by focusing on the role of normative power in the co-production process, we identified how two different forms of normative power can be created by less dominant actors through structures and resources. Building on the work of Chauhan et al. (2023), which highlights the importance of normative power that does not challenge the dominant group's control and knowledge, we illustrate three ways that normative power can be created through structures to nurture the co-production process. First, service users create opportunities to interact with academic researchers, such as attending conferences and social events, at which they would articulate their non-threatening expertise and make their valuable contribution evident to the dominant actors. Second, they generated structure-enabled normative power by using meetings (such as steering group meetings) to hold academic researchers accountable for their actions and respond to their questions and suggestions. Finally, service users drew attention to the need for their involvement in relation to broader expectations of the professional work being undertaken. In our case, researchers were required to demonstrate the tangible impact of their work to funders. As such, rather than using phrases, terms, and metaphor that align with the wider socioeconomic norms to generate normative power, as identified in previous work (Culley & Angelique, 2011; O'Mahoney & Sturdy, 2016), service users drew direct links between their involvement and wider research requirements to create structure-enabled normative power.

Alongside structure-enabled normative power, we identified three different ways that service users utilized resources to create normative power. First, we identified how less dominant actors engage in classification strategies and approach members of the dominant group with specific, variable forms of discourse. By classifying academic researchers in this way, service users adapted their language and communication style to ensure they could communicate their desired message appropriately to leverage influence. Second, services users leveraged their contextual expertise and personal networks to highlight the unique and crucial knowledge they have that could assist more dominant researchers. Third, we showed how service users do not only use expertise to connect with other members of the public, as suggested by Farr (2018), but to also connect with the researchers to build relationships, facilitating discussion of shared interests and concerns among service users and researchers. As noted previously, due to the changing nature of professional work, professionals can no longer leverage power through codified expertise and knowledge alone but rely on relational and contextual expertise (Anteby et al., 2016; Huising, 2023; Mukherjee & Thomas, 2023). We suggest that, due to the increasing value of diverse forms of expertise to dominant professional groups, service users are increasingly able to generate resource-enabled normative power to leverage influence by drawing on and highlighting their own relational and contextual expertise.

Our final contribution is the development of a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between different types of power (structure, resource, and normative power) during processes of co-production. While previous researchers have argued that resource power is the most important aspect of the process (McCabe et al., 2021), arguing that the influences of structural and normative power are minimal, we challenge this assumption. We argue that all three types of power are crucial at different stages of the co-production process, but highlight the key role of resource and structural power in the development of normative power. As shown in Figure 1, while structural and resource power are crucial to initiate co-production, co-production is only sustained in a meaningful way if non-dominant groups are able to generate structure-enabled or resource-enabled normative power. Further to this, we suggest there is a cyclical relationship between structural, resource, and normative power. As shown in Figure 1, less dominant groups can take the initiative to generate normative power from existing structures and resources and make full use of their agentic role during co-production. The creation of normative power is reliant on the agentic role of less dominant groups through mechanisms such as skilled use of distinctive discourses, mimicry, socialization, and education during the process of co-production. Once normative power for service users is created, they are subsequently able to make changes to structures and resources available, further strengthening structure and resource power of less-dominant groups. As such, we show how structural and resource power can provide a foundation to generate normative power, which in turn, reinforces structural and resource power during co-production. We highlight how normative power can help institutionalizing meaningful co-production by embedding public involvement in formalized professional practices and routines, ensuring sustained and equal interactions between academic researchers and service users.

Our work indicates that current policy is too reliant on the role of resource and structural power in processes of co-production, and largely downplays the significant influence of normative power. Given the ongoing, often frustrating, debates about how to involve service users more significantly in the planning and delivery of public services, more research is needed to understand how to generate different forms of normative power. While we illuminated the importance of structure-enabled and resource-enabled normative power, future work should further consider how the interactive and contextual expertise gained through (working) life or close contact with the public may also generate different types of normative power.

Our study also highlights the importance of the agentic role of less powerful groups (in our case service users) in co-production. While dominant groups (academic researchers in our case) should help create the right environment and empower less powerful groups in co-production (Callaghan & Wistow, 2006; Haug, 2024; McCabe et al., 2021), service users need to take an agentic role and actively create power through existing structures and resources during the process of co-production.

6 CONCLUSION

In this article, we developed understandings of processes of co-production by exploring how less dominant service users are able to influence more dominant professional groups, drawing on the empirical case of research co-production between academic researchers and service users. While extant research focuses primarily on how dominant actors utilize resource and structural power, creating tokenistic involvement, we took a more agentic view to illuminate how service users were able to leverage various types of power over more dominant actors. Specifically, we highlighted how service users create normative power through resources and structures. Finally, we showed the relationship between structural, resource, and normative power during process of co-production, extending understandings of the dynamic nature of co-production. We suggest that policy makers need to be mindful of the ways in which different types of power play out during processes of co-production and argue the need for policy to go beyond merely generating structures and resources, but give deeper consideration to how those structures and resources can be mobilized to create normative power for less dominant groups.

Building on this, we suggest future research could take a more micro lens perspective to examine why some service users are more able to leverage normative power, enabled by either structure or resource. Given the conclusions of El Enany et al. (2013), that articulate and educated service users are more likely to be involved by dominant groups, there is a significant issue of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) that needs to be considered. In particular, future work should consider whether the increased influence of service users who are able to leverage normative power has a positive or counter-intuitively negative impact on DEI within processes of co-production. Last but not least, although conducted in the United Kingdom, our research is relevant to other settings, where there are multidisciplinary work involving dominant professionals and less dominant groups in the co-production process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all interviewees for their time, as well as Editor Bruce D. McDonald III and reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments in developing this article.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) West Midlands. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.