Influences on e-governance in Africa: A study of economic, political, and infrastructural dynamics

Abstract

E-governance is considered one of the most important factors in delivering and administering public services in modern societies. However, data show that many African countries are currently lagging behind countries in other parts of the world. This manuscript investigates how various factors, including economic prosperity, government effectiveness, and infrastructural support, contribute to the growth and effectiveness of e-governance initiatives in 54 African countries. We specifically analyze the influence of three factors: economic prosperity (measured by GDP per capita), political competence (measured by government effectiveness), and infrastructural or technological support (measured by access to electricity). Panel data covering a 5-year period were retrieved from databases of the United Nations and World Bank, and a multiple linear regression analysis was used to analyze the data. We found that the three factors influenced e-governance to varying degrees. However, while infrastructural support and political competence were statistically significant, economic prosperity was not.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electronic government or e-government is often referred to as the application of information technology (IT) products and services for public administration and public service delivery (Schelin, 2007; Silcock, 2001). In recent decades, e-government has become a crucial tool for the functioning of an efficient and modern public administration system. Scholars have described the development of an efficient e-government system as a necessary factor in improving ethical behavior and transparency within the public sector, making public service delivery more cost-effective and fostering citizen participation in the democratic process (Curtin et al., 2003; Gupta & Jana, 2003; Reddick, 2010; Twizeyimana & Andersson, 2019). In addition, e-government can improve trust and confidence in governance, simplify the governing process, support business and economic growth, and help governments solve the difficult socioeconomic challenges facing its people (Basu, 2004; Fang, 2002; Reitz, 2006; Tolbert & Mossberger, 2006).

Empirical evidence from around the world supports the positive influence of e-governance on societies. For example, a study in Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines over a 52-year period revealed that e-governance reduces corruption (Sriyakul et al., 2022), and studies around the COVID-19 virus found that e-governance had a significant impact on healthcare and corporate social responsibility within some contexts (Avotra et al., 2021; Pedawi & Alzubi, 2022). Nevertheless, within Africa, e-government has largely remained underdeveloped. The 2022 United Nations (UN) e-government development index showed that South Africa was the highest-ranked African country, but was only ranked 65th in the world (UN, 2022). Meanwhile, the six least-performing countries were all African states. South Sudan was ranked bottom in the world, followed by Somalia, Central African Republic, Eritrea, Chad, and Niger. In fact, the majority of African countries rank below average in e-government development (UN, 2022).

Furthermore, from a public value perspective, e-government is not only vital for reducing the transaction costs of running public administration or making it more efficient, but it also strengthens social and democratic values such as bringing governments closer to the people, promoting citizen engagement in the democratic process, and making the overall governing process more transparent (Cordella & Bonina, 2012; MacLean & Titah, 2022; van den Berg et al., 2024). These are all desperately needed values as several African governments face an increasingly tumultuous period marked by coups and political instability. In addition to direct impacts, e-government can also lead to a wide range of indirect economic and social benefits (MacLean & Titah, 2022). Studies in development economics have revealed that high-functioning e-government can help mitigate some of the structural economic challenges facing many African countries (Dhaoui, 2022; Elbahnasawy, 2021). For instance, many African countries have a large informal economy, which has led to the exploitation of labor within the continent (Banik, 2013). Also, sustainability/climate issues, including scarcity of resources and loss of economic opportunities, are leading to terrorism and political instability in the continent (Mavrakou et al., 2022). However, extensive research on both subjects shows that e-government can reduce the scope of the informal economy and promote sustainable development (Dhaoui, 2022; Elbahnasawy, 2021).

Nevertheless, the positive benefits of e-government are not universally acknowledged in academic research. Some studies have argued that applying models of e-government implementation in developed countries is not suited to the unique needs and challenges of developing countries, such as those in Africa (Mukabeta Maumbe et al., 2008). Other studies have suggested that e-government might be driven by technology instead of the core values of government, leading to a weakening of democracy (Sundberg, 2019). In addition, issues around user participation in e-government, the digital divide in the use of IT, data security and privacy, and challenges with implementing e-government have also led to more criticisms of the concept (Sundberg, 2019). Also, scholars have highlighted the dangers of governments using e-government tools to restrict, control, and surveil citizens (Lindgren et al., 2019) and the lack of a rigorous theoretical background on the topic (Heeks & Bailur, 2007).

In spite of these challenges, the African Union (AU) has put e-government at the heart of its efforts to transform public service delivery and improve the overall socioeconomic development of the continent (NEPAD, 2022). However, research on e-government has been dominated by theoretical or conceptual approaches (Bannister & Connolly, 2015; Cordella & Iannacci, 2010; Jaeger, 2003) or by the benefits/impact of e-government (Cordella & Bonina, 2012; Pina et al., 2007). Studies on the determinants of e-government success or the factors contributing to its development have largely remained limited. Compared with developed societies, research on the determinants of e-government among developing countries, such as much of Africa, has been almost absent (Twizeyimana & Andersson, 2019). Among the few studies on factors influencing e-government success, Mensah (2020) examined the adoption of e-government among individuals, Malodia et al. (2021) conceptualized a framework for e-government within India and proposed that citizen orientation was most significant for implementing e-government, and Tejedo-Romero et al. (2022) provided a mechanism for participation in e-government. However, these studies have largely examined a small part of the e-government system, such as e-government adoption or participation, and have done so with relatively small sample sizes within a single case or country. Our paper differs from these approaches by examining e-government performance data across more than 50 countries over a longitudinal time frame. Consequently, this study provides one of the most definitive analyses of the determinants of e-government to date. This paper also provides an evidence-driven resource for policymakers, multilateral organizations, and development/aid organizations interested in improving e-government within the African continent.

Therefore, drawing on the conclusions of previous studies (Mensah, 2020; Osei-Kojo, 2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2022), this research was designed to analyze the influence of three structural factors on the e-government development of African countries. First, we used data on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita to examine the influence of economic factors. Then, we used data on government effectiveness to analyze the influence of political factors. Finally, we analyzed the influence of an infrastructural or technological factor comprising data on one of the most basic but important technologies: access to electricity. All data were retrieved from databases of both the UN and World Bank, and a multiple linear regression method was used to quantitatively analyze the data. The following sections describe our theoretical background, methodology, results, discussions, and conclusions.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Electronic governance

Ideas for using the tools of information and communication technologies (ICT) to process and deliver government services have been studied for decades (Bellamy & Taylor, 1994). Within public administration, the period from the 1980s to the 1990s saw the rise of the new public management (NPM) and reinventing government movement (Dunleavy & Hood, 1994; Hood, 1991). The core argument of NPM proponents, as well as a number of policymakers and government officials, was that public bureaucracies and programs should be radically reformed to be more efficient, cost-effective, and responsive to the demands of citizens (Ferlie et al., 1996). As such, scholars explain that NPM is primarily concerned with adopting some private sector practices to make public administration more dynamic and efficient (Hood, 1991). At the same time as the ideas of NPM were sweeping the discourse on public administration, the internet, personal computers, and other IT tools and services were not only proliferating, but increasingly forming the core part of the business models of companies (Ban Seng, 1996). Also, evidence began to mount on the benefits of adopting IT systems in companies, including improvements in productivity and overall performance and reduction in transaction costs (Capello et al., 1990; Picot et al., 1996). As a result, NPM supporters gravitated toward advocating for the use of IT systems in public administration (Bellamy & Taylor, 1994).

Electronic government or e-government—also digital government or ICT government—has been a source of great controversy since it was introduced into the academic vocabulary. There is little consensus on the precise scope, limits, or functions of e-government, and while some experts have portrayed a rather expansive notion of the concept, others have argued for a more limited scope. For example, an early definition of e-government defined it as the use of electronic means to manage the relationship between the government and its customers and suppliers (Means & Schneider, 2000). They argue that the customers and suppliers of governments can include citizens, businesses, and other government agencies or institutions. Other studies have described e-government as the use of ICT to “support public services, government administration, democratic processes, and relationships among citizens, civil society, the private sector, and the state” (Dawes, 2008), and some scholars have included a wide range of ICT products and services such as networking systems and automation, among others (Jaeger, 2003). Nevertheless, these broad definitions have been contested by scholars such as Bannister and Connolly (2012), who argue that e-government and e-governance are distinct terms that must be separated to advance studies within the field. They believe that e-governance should be more concerned with transforming the structures of governance (Bannister & Connolly, 2012). However, other scholars have established a similarity between e-government, e-governance, and other associated terms such as e-participation and e-democracy (Akman et al., 2005; Yildiz, 2007), suggesting that e-government is more akin to an umbrella term covering various iterations of these concepts.

This practical approach is also taken by leading multilateral development organizations such as the UN. According to the UN, e-government involves the “use of ICT by government for conducting a wide range of interactions with citizens and businesses as well as open government data and use of ICTs to enable innovation in governance.”1 Because this paper primarily uses data from the UN, we adopt this UN definition. Consequently, this paper takes an approach to e-government modeled after the approach of the UN and therefore equates e-government with e-governance. Nonetheless, challenges to e-government are not limited to its definition. There remains little consensus on its exact theoretical underpinnings, leading some studies to describe a “great theory hunt” to fill this gap (Bannister & Connolly, 2015). Although NPM is seen by some as the theoretical backbone of e-government (Cordella, 2007), this belief is challenged by a wide range of scholars, including those who acknowledge the overlapping but distinct nature of both elements (Homburg, 2004) and others who argue that e-government is actually a replacement for NPM (Dunleavy, 2005). In more recent years, public value theory has been gaining some traction in studies on e-government (Cordella & Bonina, 2012; Panagiotopoulos et al., 2019; Yıldız & Saylam, 2013).

2.2 Public value theory

The theory of public value can be traced to the work of Moore (1995), who envisioned a public management system focused on creating value. According to Benington (2011), public value theory is primarily concerned with two things: what the public values and what provides value to the public. Benington (2011) went on to separate public value from traditional public administration, which he argues was influenced by Keynesian economics and the theory of public goods, and NPM, which was influenced by markets and neo-liberal approaches to public choice. Instead, public value is shaped by a commitment to democracy and a networked approach to governance characterized by systems of dialog and exchange, bringing together civil society and community governance (Benington, 2011; Moore, 1995; Stoker, 2006).

Moore (1995) introduced the concept of a “strategic triangle,” which forms the basis of public value theory. Proponents of the strategic triangle argue that public managers can enhance public value by putting great focus on political or democratic legitimacy, public value, and operational feasibility (Bryson et al., 2017; Moore, 1995). The networked interconnection of these three forces can lead to a more efficiently run public administration system that is grounded in civic and democratic principles (O'Flynn, 2007). This approach, which emphasizes collaboration and value co-creation, has become the new normal in public administration (Torfing et al., 2024). Furthermore, public value is increasingly applied to studies on e-governance. Proponents of this approach believe that it goes beyond the efficiency and customer orientation of NPM and leads to the creation and maintenance of socially shared expectations of fairness, trust, and legitimacy (Panagiotopoulos et al., 2019). Accordingly, a public value approach to e-governance also considers social and political outcomes, not simply economic or financial ones (Cordella & Bonina, 2012).

A number of studies have looked into the impact of e-government from a public value perspective. For example, a review study by Twizeyimana and Andersson (2019) found that e-government practices grounded in public value approaches led to improvements in public service delivery, administrative efficiency, open government efforts, improved social value and well-being, and a more ethical and professional public administration system. Another review study found that e-government contributes to creating public value by fostering improvements in public transparency and reducing corruption. It can also increase public trust, strengthen the relationship between citizens and their government, foster innovation, and promote client satisfaction (MacLean & Titah, 2022; Olumekor, 2024). Other studies show that e-government initiatives can improve democracy by promoting a more participative, collaborative, and transparent public environment (Harrison et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2024; van den Berg et al., 2024).

2.3 E-governance in Africa

Initiatives to inspire the development of e-governance in Africa have existed for several decades. The UN Economic Commission for Africa launched the African Information Society Initiative in 1996 to develop and promote Africa's digital vision, including e-government services. Furthermore, since the formation of the AU in 2002, the organization has championed the importance of e-government services for promoting good governance and efficiency in service delivery. The AU introduced an e-government framework to offer guidelines related to policy, strategy, infrastructure, and human capital (Osei-Kojo, 2017). It has also established a number of key initiatives to promote the development of e-government and other electronic services. For instance, the AU created the NEPAD e-Africa Commission in 2002, and recently, the AU High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies and the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa were also created. The goal of the e-Africa Commission is to make ICT a priority sector and facilitate digital integration, information society, and knowledge economy in Africa, whereas the High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies is particularly concerned with using ICTs to improve the service delivery of government (NEPAD, 2022). Finally, the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa is a plan to use digitalization to promote job creation and the overall sustainable development of the continent (African Union Commission & OECD, 2021).

According to the AU High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (NEPAD, 2022), one of the biggest challenges facing public administration in Africa is the fractured and uncoordinated communication between government departments, leading to restrictions in information access and poor efficiency in governance. Research shows that even in developed societies, fragmentation can lead to persistent challenges for public administrators (Andersen & Breidahl, 2025). Consequently, African governments and multilateral institutions have promoted e-governance as a potential solution. E-government in Africa can promote public participation in important governance activities, including electoral participation, payment of taxes, application for documents such as passports and marriage, birth, and death certificates (NEPAD, 2022). In addition, studies show that e-government initiatives in African countries have led to improved governance, enhanced public service delivery, and progress toward attaining the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Dhaoui, 2022; Paul & Adams, 2024). However, studies have also shown that many African countries face persistent challenges in implementing e-government (Osei-Kojo, 2017). While studies in other parts of the world, such as the United States, also highlight challenges in achieving the full benefits of e-government (Baxter, 2017), issues such as ICT infrastructure and electricity access make the challenges in Africa more pervasive (Osei-Kojo, 2017).

3 DATA AND METHODS

All data used in this research were retrieved from the respective databases on September 15, 2023. Data on the development of e-government across Africa were sourced from the e-government development index compiled by the UN. The UN e-government development index is a composite index comprising three main indicators: the provision of online services within a country, the level of telecommunication connectivity, and the level of human capital development. The index assigns a score and rank to all 193 member states of the UN. Whereas, data on economic factors were retrieved from the World Bank's World Development Indicators database. The World Bank's world development indicator database includes an exhaustive list of hundreds of social, economic, and political data on countries around the world. All data used in this research are open-access and are available on the respective websites of the UN and World Bank, as presented in the data availability statement.

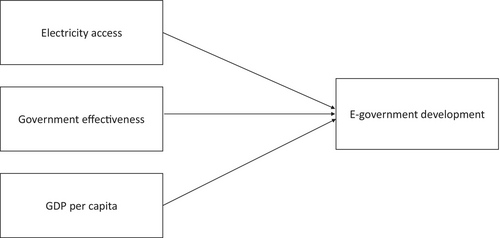

After retrieving the research data, it was necessary to decide precisely which economic, infrastructural, and political indicators to include in our analysis. First, because the e-government index already includes vital indicators such as knowledge/skills and telecommunications infrastructure, these data were immediately excluded from our dataset. Also, due to the influence of population size on many aggregate economic data such as the GDP and gross national product, a decision was made to consider data that factored in population size. As such, GDP per capita was chosen as the preferred indicator, alongside other vital metrics. In total, three main metrics were chosen for the analysis. These include the percentage of the population with access to electricity, GDP per capita, and government effectiveness. This is expressed in our conceptual model in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model used in this study. Electricity access was selected because of the central role it plays in the provision of internet access that e-government requires. Moreover, studies have shown that electricity access is one of the most significant challenges for implementing e-governance in Africa (Osei-Kojo, 2017). In addition, technological tools that are necessary for e-government, such as telephones and computers, require electricity to function either directly or indirectly via rechargeable batteries. GDP per capita was selected because it is one of the most widely used measures of economic performance (Maddison, 1983). Furthermore, studies have consistently shown that GDP per capita remains one of the most important measures of economic activity within Africa (Gil-Alana et al., 2021; Henri, 2019). Finally, data on government effectiveness was chosen because it was considered a key factor for measuring political competence and connected all other issues within a country. Government effectiveness is considered a “measure of the quality of output and how well policy achieves desired objectives” (Duho et al., 2020). According to the World Bank data used for this research, government effectiveness measures the “perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government's commitment to such policies.” (Kaufmann & Kraay, 2023). Prior studies on Africa have demonstrated the influence of governance factors on e-government development (Akpan-Obong et al., 2023). Thus, in the context of this study, we postulate that the competence of governments to formulate and implement e-government policies is crucial for the development of e-government within a country. As a result of the aforementioned factors, this research seeks to test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.Economic, political, and infrastructural factors—measured by access to electricity, GDP per capita, and government effectiveness—will influence the e-government development of African countries.

H1a.Access to electricity influences e-government development in Africa.

H1b.GDP per capita influences e-government development in Africa.

H1c.Government effectiveness influences e-government development in Africa.

All data were sent to a Microsoft Excel worksheet for sorting and processing, and the final dataset was panel data covering a 6-year period from 2018 to 2022 for all 54 African countries. However, data on electricity access and government effectiveness were not available for 2022. Also, Eritrea and South Sudan were excluded for having no data on any of the metrics for the 6-year period, thereby leaving a total pool of 52 countries. Following this, a multiple linear regression model was fitted for data analysis. The e-government index was taken as the outcome variable, while electricity access, GDP per capita, and government effectiveness were the predictor variables. The results of the assumption checks and regression analysis are presented in the following sections and subsections.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Data and model assumptions

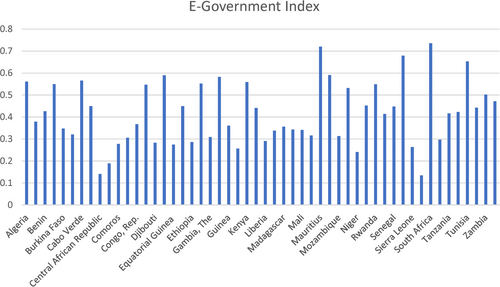

Figure 2 shows the e-government development index of 52 African countries for 2022. The figure shows that fifteen African countries scored above the average of 0.5 and can, therefore, be ranked as having a high or medium level of e-government development. South Africa led the continent in e-government development, followed by Mauritius, Seychelles, Tunisia, and Morocco. Meanwhile, at the other end, Somalia, the Central African Republic, and Chad scored the least. Furthermore, before beginning the linear regression analysis, it was necessary to check if our data met the core assumptions of linear regression. The first assumption is to check for outliers in our data using one of the most popular methods: Cook's distance test (Cook, 1977).

Table 1 shows the results of Cook's distance test for data outliers. The result of our Cook's distance test is less than 1, which means that we can reasonably assume that there are no problems with outliers in the dataset. Furthermore, a core part of any linear regression is to check for a linear relationship or the normality of the residuals. To achieve this, we use the quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot (Altman & Krzywinski, 2016; Easton & McCulloch, 1990).

| Range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

| 0.0101 | 0.00357 | 0.0167 | 5.21e−6 | 0.0873 |

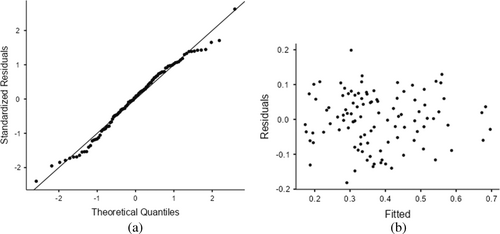

Figure 3 shows the results of the Q–Q plot (Figure 3a) and the plot of residuals for linearity (Figure 3b). The result of the Q–Q plot shows a normal linear distribution among the residuals of the model, signifying the reliability of our approach and analysis. Also, the random nature of Figure 3b shows that our model satisfies the assumption of linearity and homoscedasticity. Following this analysis, we tested for the absence of multicollinearity in the model. Multicollinearity is one of the most important assumptions of a linear relationship and regression, and it examines whether there is a high degree of correlation between the predictor or independent variables (Gunst & Webster, 1975). Because predictor variables should be independent, a high degree of collinearity would signify a high level of similarity between the predictor variables and would, therefore, cast serious doubts on the reliability of our results (Alin, 2010). The results of our multicollinearity test are presented below.

The results of the multicollinearity test are presented in Table 2. It shows a low variance inflation factor above 1 for all predictor variables. This signifies the absence of multicollinearity in the variables and is further strengthened by the tolerance levels of the predictor variables.

| VIF | Tolerance | |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity access | 1.85 | 0.540 |

| Govt Effectiveness | 1.48 | 0.675 |

| GDP per capita | 1.75 | 0.570 |

- Abbreviation: VIF, variance inflation factors.

4.2 Regression results

Table 3 shows the results of the goodness of fit for the model used in our analysis. Our model fit summary shows an F-test with a statistically significant model at a probability of 1% or p < 0.001. Furthermore, the results of the R2 and adjusted R2 show a high degree of influence and that the core assumptions and hypothesis of this research are correct. The R2 test shows that approximately 71.5% of the change in the e-government development performance of African countries is due to the three factors of electricity access, government effectiveness, and GDP per capita.

| R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.846 | 0.715 | 0.707 | 83.7 | 3 | 100 | <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: df, degree of freedom; F, F-test.

The main results of the linear regression analysis are presented in Table 4. Table 4 shows a positive influence of all the predictor variables—access to electricity, GDP per capita, and government effectiveness—on the e-government performance of all countries in Africa. However, while electricity access (β = 0.3742, t = 5.154, p < 0.001) and government effectiveness (β = 0.5495, t = 8.464, p < 0.001) were significantly influential, GDP per capita (β = 0.0513, t = 0.725, p = 0.470) was not. Moreover, of the three predictor variables examined in this research, government effectiveness was the most influential factor in determining the e-government performance of African countries.

| 95% Confidence interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | t | p Value | Stand. estimate | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 0.35214 | 0.0272 | 12.939 | <0.001 | |||

| Electricity access | 0.00202 | 3.91e−4 | 5.154 | <0.001 | 0.3742 | 0.2302 | 0.518 |

| Govt Effectiveness | 0.12214 | 0.0144 | 8.464 | <0.001 | 0.5495 | 0.4207 | 0.678 |

| GDP per capita | 2.49e-6 | 3.44e−6 | 0.725 | 0.470 | 0.0513 | −0.0890 | 0.191 |

- Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

5 DISCUSSION

This research looks into the state of e-government development in Africa and the factors that influence it. We hypothesized that access to electricity, wealth or economic prosperity measured by GDP per capita, and government effectiveness are likely to influence the development of e-governance. To test this hypothesis, we used a linear regression model to analyze panel data for all 54 African countries over a 5-year period. The results of the analysis showed that our model and all three factors were very influential and responsible for a variance of over 70% (adjusted R2). This means that 70% of the change in e-government development in African countries can be explained by electricity access, economic prosperity, and government effectiveness.

In addition, looking at the influence of each of the three factors, we found that government effectiveness was the most influential factor. This conclusion is supported by some previous studies which found that political factors play a leading role in the adoption of e-government. For example, studies show that political factors such as political trust, government capacity, and government performance determine the level of e-government development (Mensah, 2020; Mensah & Adams, 2020). Other studies have described the influence of different types of political factors such as institutional effectiveness and political leadership (Apriliyanti et al., 2020; Stratu-Strelet et al., 2021). Similarly, we also found that access to electricity significantly influenced the development of e-government. This is supported by previous studies on African countries (Abusamhadana et al., 2021). Since the technological tools required for e-government implementation and access require electricity, it is no surprise that countries with higher electricity access tend to perform better in e-governance. Research shows that electricity access remains poor in Africa and negatively impacts both economic growth and digital transformation (Blimpo & Cosgrove-Davies, 2019).

In addition, studies on Africa show that political effectiveness influences electricity access, which also influences income inequality (Sarkodie & Adams, 2020). The influence of electricity access ties into the influence of overall infrastructure, such as cloud computing and internet access, which research shows is important for fostering e-government development (Antoni et al., 2019; Mudawi et al., 2020). Finally, our results show that while economic prosperity positively influences e-government development, this influence is only marginal and not statistically significant.

6 THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL CONTRIBUTIONS

This paper makes a number of contributions to both existing knowledge and practice. First, this paper answers the call of recent studies (see, e.g., Twizeyimana & Andersson, 2019) on the need for more research into the e-government of developing countries, especially those in the global south, many of which are in Africa. Consequently, this paper expands the range of debate on the determinants of e-government success by examining one of the most under-studied regions of the world on the topic. Second, we enhance the understanding of the factors that enable a thriving e-government environment as electronic technologies or IT continue to play an outsized role in the social, political, and economic lives of people around the world. Furthermore, unlike prior studies on the determinants of e-government, which have tended to be narrow in scope, this research argues that any holistic understanding of e-government in developing countries cannot simply be limited to single issues such as wealth, infrastructure, or political support (Mensah, 2020; Osei-Kojo, 2017). Instead, it must connect all three factors. This fact is demonstrated by the significant cumulative weight of all three factors in our study (see Table 3).

In addition, although a considerable number of studies have taken a public value perspective (MacLean & Titah, 2022) and shown the enormous political benefits of e-government (Stratu-Strelet et al., 2023; Tolbert & Mossberger, 2006; Zou et al., 2023), this paper contributes to the nascent debate on studies showing the reverse effect. That is, political factors influence e-government success. Furthermore, by analyzing actual data over multiple years, rather than data from individual surveys and interviews, this paper provides significant implications and evidence for policymakers, public managers, and development/aid organizations. Our conclusions, showing that political effectiveness is the most significant influencer of e-government success, imply that strengthening political and democratic institutions might be the best way to increase the performance of e-governance within African countries. Since e-government depends on a great deal of trust between citizens and public workers (Mensah & Adams, 2020; Pérez-Morote et al., 2020), policies that help to foster political trust and competence should be prioritized. However, this cannot be achieved in the absence of a supportive infrastructural environment. Crucial enabling infrastructure, such as electricity access and broadband coverage, should be supported.

Finally, we argue that e-governance in Africa should be developed from a public value perspective, not a market efficiency one. Several studies on developing countries and developed societies have shown that introducing the sort of market efficiency approaches advocated by NPM, which often prioritizes cost reduction and privatization, can lead to additional or even worse outcomes for society (Diefenbach, 2009; McCourt, 2008). Research also shows that NPM can worsen challenges for people in the bottom rungs of society who depend on government support, such as the poor and homeless (Farr, 2016). These issues can have disastrous consequences for a continent facing intense socioeconomic challenges, such as Africa. Instead, a public value approach to e-governance encourages having a balance between what public services deliver, how these services are delivered, and what society expects of them (Panagiotopoulos et al., 2019). While e-government can certainly be used to make public administration more effective, the guiding principles should be a broader approach toward public value, including improving governance, democratic accountability, public trust, and citizen–government relationship (Cordella & Bonina, 2012).

7 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Some important limitations should be considered while interpreting the results of this study. First, the three factors examined in this research should by no means be considered exhaustive. Extensive studies on similar areas of IT, such as electronic commerce, have revealed that a wide range of factors can influence the adoption, usage, and development of Internet tools and services. For example, good quality internet access remains crucial to the development of online systems, and digital literacy, poverty, and a number of individual factors can also influence online services (McGuirt et al., 2022; Olumekor et al., 2024). Moreover, research on the digital divide has highlighted the presence of a gender divide, a rural–urban divide, and an age-related divide (Friemel, 2016; Lai & Widmar, 2021; Mumporeze & Prieler, 2017; van Dijk, 2020). All of these can represent potential avenues for future research within the context of e-government. Furthermore, although this paper only examined the influence of economic performance, government effectiveness, and access to electricity, the e-government data used for this study is a composite measure that aggregates knowledge/skills within a country, the performance of online services, and the quality of telecommunications infrastructure.

In addition, this research did not investigate the potential impact of historical injustices, such as colonialism and exploitation, on the current development of e-government in Africa. There is a well-established body of literature within the internet economy showing that historically marginalized groups do not use online tools and services as much as other groups (Francis & Weller, 2022; Intahchomphoo, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2019). These studies reveal that this disadvantage is prevalent among racial minorities and indigenous communities. Therefore, future studies on Africa that consider the overarching influence of these issues can provide a much-needed context for studies on e-government within the continent. Another potential avenue for future research on e-governance in Africa is the role of ethnic divisions and conflicts. In recent years, a rising number of studies have begun to highlight the challenges of reaching political consensus and support in countries with diverse ethnic groups, particularly those with a relatively short period of co-existing as nation-states, such as much of Africa (Bluhm & Thomsson, 2020; Franck & Rainer, 2012). While much evidence suggests that ethnic diversity can lead to economic prosperity and sociocultural progress (Bove & Elia, 2017; Page, 2008), there can be historical grievances between ethnic groups that were forced into becoming nation-states with other nationalities through colonial conquest. In such cases, ethnic polarization can have negative effects on economic development and lead to poverty and political challenges (Churchill et al., 2019; Esteban et al., 2012; Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005). This also offers an interesting avenue for future research.

Other potential avenues for future studies can be the role of cultural differences in influencing the development of e-government. Due to the huge cultural diversity in Africa, some prior studies have argued that only a multi-cultural approach to e-government can be successful in Africa (Mukabeta Maumbe et al., 2008). However, studies examining the influence of cultural differences have so far remained scarce. In addition, studies can also examine if African states can potentially skip some stage/s in the process of developing e-government services. As advanced technologies continue to proliferate, e-government services can potentially skip certain stage(s) that counties in other parts of the world went through, providing opportunities to learn from the challenges/mistakes of other parts of the world in providing public value through e-government. Finally, the influence of issues such as cybersecurity, privacy, identity theft, and many other challenges that e-government might face in Africa also require further exploration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Michael Olumekor and Sergey N. Polbitsyn acknowledge funding from the Ural Federal University (Ministry of Science and Higher Education) project within the Priority-2030 program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Endnote

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data used for this study are openly available in the Harvard dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SSTKS8. Data on the e-government development index can be downloaded from the United Nations: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/Data-Center. Other economic and political data can be downloaded from the World Bank: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Accessed on September 15, 2023.