Deservingness at the frontline: How health-related responsibility cues affect sanctioning and prioritization of citizens

Abstract

enDeservingness literature has shown that people, including frontline workers, spontaneously judge whether welfare recipients are responsible for their own situation or are victims of circumstances beyond their own control, and that these judgments shape behaviors and opinions. We contribute to this literature by examining the impact of clients' responsibility for their own sickness on how the clients are treated by frontline workers. Using a pre-registered vignette survey experiment among 1050 caseworkers, we examine our hypothesis that frontline workers treat clients who are responsible for their own sickness more harshly. In the experiment, we manipulate whether a client got COVID-19 because of his own behavior or was unlucky to catch it. We find that although the manipulation strongly influences frontline workers' responsibility attribution, it does not affect inclinations to help or sanction the client. Our findings highlight that factors other than deservingness are important for frontline workers' prioritization of sick citizens.

Abstract (Danish)

esDeservningness på frontlinjen: Hvordan sundhedsrelaterede cues påvirker sanktionering og prioritering af borgere

Deservingnesslitteraturen har vist, at individer, herunder frontlinjearbejdere, anvender cues om arbejdsløses grad af kontrol, når de vurderer, om arbejdsløse selv er ansvarlige for deres situation eller ofre for uheldige omstændigheder. Disse vurderinger er centrale, idet de både former holdninger og adfærd. I nærværende studie bidrager vi til denne litteratur ved at undersøge, om kontanthjælpsmodtagere, der har handlet på en måde, der tillægger dem en vis grad af ansvar for deres situation, også bliver behandlet hårdere af frontlinjemedarbejdere. Til formålet benytter vi et præregisteret spørgeskemaeksperiment blandt 1.050 sagsbehandlere, der arbejder på de danske jobcentre. I eksperimentet manipiulerer vi, om en kontanthjælpsmodtager selv var skyld i, at vedkommende fik COVID-19, eller om kontanthjælpsmodtageren var uheldig at få sygdommen. Vores eksperimentelle stimuli lykkedes med at påvirke sagsbehandlernes vurdering af, om kontanthjælpsmodtageren kan tillægges mere eller mindre ansvar for at blive syg. Vi finder til gengæld ingen effekter af vores stimuli på sagsbehandlernes villighed til at hjælpe eller sanktionere kontanthjælpsmodtageren. Resultaterne understreger derfor, at andre faktorer end deservingness cues er vigtige for frontlinjemedarbejderes adfærd overfor syge borgere.

1 INTRODUCTION

Extant scholarly research has demonstrated how perceptions of welfare recipients' deservingness are important in shaping welfare-related attitudes and behaviors among citizens (Aarøe & Petersen, 2014; Jensen & Petersen, 2017). A key argument in the literature is that deservingness perceptions are often formed based on cues about welfare recipients' level of responsibility for their situation (Petersen et al., 2010). In general, generous attitudes tend to be formed toward welfare recipients as long as they are not viewed as responsible for their need for benefits (i.e., as long as they are seen as unlucky victims of external circumstances). However, welfare recipients who are viewed as responsible for their situation (e.g., people who do not show an interest in providing for themselves) are more often judged as undeserving of help (Ibid.). Building on these insights, recent research in public administration has begun to examine how frontline workers' sanctioning behavior, prioritization of clients, and enforcement of burdensome policies are affected by deservingness-related perceptions (Guul et al., 2021; Jilke & Tummers, 2018; Pedersen et al., 2018; Petersen, 2021; Soss et al., 2011). For example, studies have found that frontline workers' deservingness perceptions are affected by cues about citizen attributes such as motivation and competence (Guul et al., 2021) as well as their performance and effort (Jilke & Tummers, 2018).

In this paper, we add to this burgeoning public administration literature on the role of deservingness cues by studying the role of health-related cues in relation to frontline workers' attitudes and behaviors toward citizens. Despite some attention to health in political-psychological research on deservingness cues in relation to the attitude formation of the general public (e.g., Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Reeskens et al., 2021), little is known about the impact of health-related cues in relation to frontline workers' attitudes and behaviors. This is problematic as in many key areas of the public sector, frontline workers are being confronted on a daily basis with government welfare recipients suffering from various kinds of health problems. This is most obviously the case in the health sector but also in other areas such as the employment sector where unemployed clients often struggle with health problems (Andreeva et al., 2015; Paul & Moser, 2009). Thus, in this article, we set out to study the impact of cues related to citizens' health problems.

Drawing on prior political-psychological research, we hypothesize that frontline workers will be less willing to help and more willing to sanction sick clients if cues make them think that the clients are responsible or can be blamed for being sick. On the other hand, we hypothesize frontline workers to be more willing to help and less willing to sanction in cases where cues make them think that clients are not responsible for being sick. We test these pre-registered hypotheses using a survey experiment among 1050 caseworkers working in Danish unemployment agencies.1 The Danish unemployment sector constitutes a good case for a test of our hypotheses. For instance, the caseworkers are regularly confronted with clients struggling with health problems (see e.g., Ydelseskommissionen, 2021, pp. 64–66). Moreover, the caseworkers are responsible for implementing the rules and regulations of the Danish unemployment benefit system, meaning that they are, among other things, responsible for determining clients' eligibility for help and for sanctioning violations of rules and requirements in relation to receiving benefits.

In our survey experiment, we ask the caseworkers to react to a rule breach by a client suffering from long COVID, and we provide cues about the client's own responsibility for catching the infection. At the time of the survey, the COVID-19 pandemic was very salient in Denmark as the country was experiencing its second big wave of infections, causing the country to be in partial lockdown. Thus, strong moral perceptions were in place regarding responsible and irresponsible conduct.

The results of our experiment show that frontline workers do attribute significantly more responsibility to clients for their sickness if they got infected while engaging in irresponsible behaviors (participating in a big party at a time when authorities urged people to see as few people as possible) compared with if they got infected while engaging in responsible conduct (grocery shopping).2 However, even though the manipulation of the client's perceived responsibility was effective, the frontline workers are not more inclined to sanction or less inclined to help clients who they perceived as responsible for getting sick. We discuss the implications of these results as well as for future research on the role of the deservingness heuristic in citizen-state interactions.

2 THEORY

To form hypotheses about frontline workers' decision-making toward welfare recipients, we turn to insights from political psychology about the role of the deservingness heuristic in shaping welfare-related attitudes among citizens (Aarøe & Petersen, 2014; Gilens, 2000; Guul et al., 2021; Petersen, 2012; Petersen et al., 2010; van Oorschot, 2000; Van Oorschot et al., 2017). According to this literature, people's willingness to help others and support for public benefits programs tend to depend strongly on cues about why people need help. As noted by Aarøe & Petersen (2014, p. 686), “needy individuals who are viewed as being responsible for their own situation are judged as undeserving of help, whereas those who are viewed as victims of circumstances beyond their own control are judged as deserving.”

The deservingness heuristic has been found to operate automatically (Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Petersen, 2012) by triggering emotions of anger toward undeserving individuals and compassion toward deserving individuals (Brandt, 2013; Hansen, 2023; Petersen et al., 2012). According to political psychologists, the deservingness heuristic represents a universal, deep-seated psychological orientation towards reciprocity in relation to sharing resources, which has been adapted throughout human evolutionary history. Thus, as human beings, we have a strong interest in targeting help towards people who will likely reciprocate while avoiding spending resources on people who will not do so (Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Petersen, 2012, 2015).

In political science, most research on the deservingness heuristic has focused on citizens' welfare attitudes, including their willingness to provide welfare benefits to people in need (Buss, 2019; Geiger, 2021; Kootstra, 2016; Larsen, 2008; Petersen et al., 2010; van Oorschot, 2006). However, deservingness cues have been found to matter in relation to a broader range of policy areas as well, including immigration policies (Kootstra, 2016) and COVID-19 vaccines (Reeskens et al., 2021). Moreover, in addition to people's willingness to provide help, deservingness cues also shape people's willingness to impose burdens on the individuals who receive help (Schneider & Ingram, 1993). In the context of unemployment benefits, for example, people tend to become more supportive of burdensome compliance demands such as mandatory work requirements if cues prompt them to view welfare recipients as responsible for not having a job (e.g., because they are lazy) compared with welfare recipients perceived as unlucky (Baekgaard et al., 2021; Petersen et al., 2010).

2.1 The deservingness heuristic and decision-making at the frontline

Most prior research on the impact of deservingness cues has focused on the attitude formation of citizens (e.g., Petersen et al., 2010; Van Oorschot et al., 2017) and, in rare cases, politicians (Aarøe et al., 2021; Baekgaard et al., 2021). We aim to investigate whether the attitudes and behavior of frontline workers are affected by deservingness cues, particularly frontline workers' willingness to help or sanction sick unemployment welfare recipients. Building on the empirical evidence about the impact of the deservingness heuristic among citizens in general, we should expect deservingness considerations to impact decision-making among frontline workers. However, deservingness considerations might collide with core public values such as impartiality and equity (Lapuente & Van de Walle, 2020). Thus, frontline workers, such as the social caseworkers in our investigation, may adhere to professional norms of equity and impartiality. When frontline workers adhere to professional norms in the decision-making process, they may disregard all pieces of information that are not strictly relevant to form a professional judgment. If that is the case, this could potentially weaken the impact of deservingness cues.

Although professional norms may potentially weaken the effects of deservingness cues, it is at the same time worth noting that deservingness-related factors have been pivotal in building expectations about frontline workers' decision-making concerning clients. For instance, in Lipsky's seminal work from 1980, it was argued that street-level bureaucrats' prioritization of clients would be based on the perceived worthiness and need for help among the clients (Lipsky, 1980). In line with this, studies have demonstrated that deservingness perceptions do indeed affect street-level bureaucrats' prioritization of clients (Guul et al., 2021; Jilke & Tummers, 2018) as well as sanctioning behavior towards clients (Pedersen et al., 2018; Petersen, 2021; Soss et al., 2011). Therefore, we expect that frontline workers' decision-making will be affected by deservingness cues.

2.2 Sickness and deservingness perceptions

In this article, we investigate the impact of sickness-related deservingness cues on frontline workers' willingness to help or sanction sick welfare recipients. When forming theoretical expectations about the impact of a sickness-related cue, it should be noted that there is reason to expect attitudes towards sick individuals to be less affected by deservingness cues than attitudes towards other groups of citizens. Importantly, Jensen and Petersen (2017) theorize a human bias towards perceiving sick individuals as generally deserving (i.e., a tendency to unconsciously tag sick individuals as unlucky no matter the reason for an individual's illness). Using different survey experiments, Jensen and Petersen (2017) find evidence in support of this as the impact of controllability cues is found to be weaker in the context of healthcare than in the context of unemployment benefits.

At the same time, however, even if sickness-related controllability cues have less influence than unemployment-related cues, this does not mean that sickness-related cues do not matter for attitude formation and behavior. In Jensen and Petersen's (2017) experiments, controllability cues do have an effect, even in the context of healthcare (the effects are just weaker than in other contexts), and the authors also find differences in people's willingness to help sick individuals depending on the kinds of sickness they suffer from. For example, people are more willing to help in case of cancer and asthma compared with obesity or smoking-related chronic bronchitis, arguably because of the latter being perceived as more related to people's own behavior (Jensen & Petersen, 2017, pp. 80–81). Moreover, other studies have found effects of controllability cues on people's sickness-related help-giving attitudes. Murphy-Berman et al. (1998), for example, find that people are less willing to prioritize Medicaid funds to patients who are described as being responsible for the onset of their sickness compared with patients who are not responsible for their sickness. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies have demonstrated high levels of moral condemnation of individuals who do not adhere to infection-preventive behaviors (Bor, Jørgensen, Lindholt, & Petersen, 2023; Bor, Jørgensen, & Petersen, 2023) as well as a prevalent willingness to punish nonadherence financially (Weisel, 2021) or through restricted access to scarce healthcare resources (hospital beds, etc.) (Reeskens et al., 2021; Schuessler et al., 2022). Based on the existing evidence, we thus expect sick welfare recipients' responsibility for their sickness to have an impact on frontline workers' willingness to help and sanction welfare recipients. Our expectations are summarized in the following two hypotheses:

H1.Frontline workers are less willing to help welfare recipients who are responsible for their own sickness compared with welfare recipients who are not responsible for their sickness.

H2.Frontline workers are more willing to sanction welfare recipients who are responsible for their own sickness compared with welfare recipients who are not responsible for their sickness.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Empirical setting

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a survey experiment among social caseworkers at Danish unemployment agencies. Danish unemployment agencies constitute a good test case for at least three reasons. First, caseworkers in Danish unemployment agencies have a large degree of discretion when making decisions (Pedersen et al., 2018; Petersen, 2021). Discretion in decision-making (and hence variation in decision-making) is required to identify any effects of health-related deservingness cues, making it essential for our test case. Secondly, social caseworkers in Danish unemployment agencies regularly interact with and make decisions concerning clients who struggle with various health-related problems (see, e.g., Ydelseskommissionen, 2021, pp. 64–66). This means that caseworkers are familiar with dealing with clients who have health problems. Finally, we believe that the Danish unemployment agencies constitute an important test case because they make decisions that critically influence welfare recipients' outcomes. Thus, social caseworkers make decisions concerning eligibility to different services and programs, and they have the discretion to sanction recipients that do not fulfill rules or requirements. Such economic sanctions can have a major impact on welfare recipients' financial stability and well-being.

3.2 Survey experiment

In our survey experiment, we asked caseworkers to read a vignette describing an unemployed citizen, Mathias, who—without notice—has not shown up at a mandatory employment activity. The vignette describes how a few months before the incident, the citizen contracted COVID-19, which caused a 2-week sick leave. He excuses his current no-show with severe headaches, which he has developed as a long-term complication of the COVID-19 infection—information that is corroborated by a medical statement from his general practitioner. Finally, to enable a test of our hypotheses, we randomized the vignette's information about how he was infected. In one condition (the low-controllability condition), he contracted COVID-19 while grocery shopping, whereas in the other condition (the high-controllability condition), he was infected while attending a big New Year's celebration. After reading the vignette, caseworkers were asked how they would respond to the situation in terms of helping and potential sanctioning. See Table 1 for the full wording of (the different versions of) the vignette.

| Mathias is 31 years old and a job-ready cash welfare recipient. In early January 2021, Mathias was diagnosed with COVID-19 after [going shopping/attending a big New Year's celebration]. The course of the disease lasted 2 weeks, but since then, Mathias has been declared fit for work. |

| Mathias has no education other than primary school, and his main work experience is as a warehouse worker. Following his illness, Mathias has been given a four-week work placement in a local company. Three weeks into the traineeship, Mathias' manager in the company contacts Mathias' caseworker. Mathias' manager tells him Mathias has not turned up for the past 3 days and has not given notice. |

| Mathias' caseworker then contacts Mathias. Mathias says that he is suffering from long-term effects of COVID-19, which have given him severe headaches, and that is why he has been unable to attend. Mathias' doctor confirms that it is likely that Mathias' may suffer from long-term effects of COVID-19. Mathias has not previously been sanctioned. |

The case of COVID-19 is well suited to test our hypotheses because of the strong norms about responsible and irresponsible behavior that were developed in relation to this pandemic. In relation to most diseases (even lifestyle diseases, where individual behavior is a significant risk factor), determining the extent of an individual's responsibility for their sickness is complicated by the fact that factors such as genetic predispositions and environmental factors may cause sickness as well (Jirtle & Skinner, 2007). During the COVID-19 pandemic, even though the risk of (accidental) infection was far from equally distributed,3 authorities across the globe appealed strongly to (and sometimes even enforced) infection-preventive behaviors such as social distancing, masking, and vaccine take-up. Moreover, as discussed above, people's adherence to infection-preventive behaviors has been a highly moralized issue in relation to the pandemic (Bor, Jørgensen, Lindholt, & Petersen, 2023).

Regarding the specific wording of our experimental material, it should be noted that the 2020 New Year's Eve (where the high-controllability version of our vignette's citizen was infected) coincided with the peak of Denmark's second wave of infections, which happened in the winter of 2020–21. Thus, COVID-19-related hospitalization and mortality numbers had never been higher (Mellerup, 2021; SSI, 2022), and therefore, in the weeks leading up to the new year, the government and national health authorities emphasized the need to limit celebrations to prevent infections. The rhetoric culminated at a high-profile press conference on December 29, which was broadcasted live to almost 2 million Danes (more than 40% of the adult population) according to viewership numbers from the major national TV stations (Hansen, 2022). Here, the Prime Minister made it clear that “given the current situation, with a lockdown of Denmark (…) and the huge costs that come with it (…), it would not be fair if a New Year's celebration leads to even more spread of infection” (The Prime Minister's Office, 2020, own translation from Danish). Moreover, the director of the National Board of Health said, “If you have planned a New Year's Eve with people you don't normally see, then cancel those plans. If you need to have dinner with someone, then do it with as few as possible. (…) Stick to your household and maybe a few of your closest relatives. (…) If we have all contributed to not letting the epidemic get out of hand, then we have celebrated New Year's the right way” (The Prime Minister's Office, 2020). In other words, the moralized nature of people's individual behavior was extremely prevalent in the context of New Year's Eve, which we utilize in the study.

3.3 Data collection

We contacted the managers from all 94 Danish local unemployment agencies and invited them to participate in our survey. A total of 32 unemployment agencies agreed to participate. Our sample of unemployment agencies is diverse in terms of geography and population. Importantly, as can be seen in Table 2, the sample of unemployment agencies is representative on key variables such as share of non-Western immigrants and share of unemployed citizens.

| Participating | Nonparticipating | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhabitants in municipality (mean) | 72,102 | 53,804 | 18,298 |

| Socioeconomic index | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.05 |

| Share of non-Western immigrantsaa | 4.45 | 4.10 | 0.35 |

| Share of unemployedb | 4.47 | 4.66 | 0.19 |

| Share of cash welfare recipientsb | 2.17 | 1.98 | 0.19 |

- Note: Based on administrative data gathered from www.noegletal.dk, www.dst.dk, and www.jobindsats.dk. Reprint from Halling and Petersen (2024). ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

- a As percentage of the whole population.

- b As percentage of the workforce.

In accordance with our preregistration, the data collection lasted from February 23 to March 23, 2021. Throughout this period, everyday-life in Denmark was still highly restricted by measures that were introduced in response to the second wave of infections. There were, for example, restrictions in children's access to school, and restaurants, cafes, cultural institutions, and the like were closed. An assembly ban was also in place prohibiting public gatherings of more than five individuals (during the last 2 ays of the data collection, the assembly ban was relaxed, allowing outdoor gatherings of up to 10 individuals). The pandemic (and the continued need to limit infections) was still very prevalent in people's minds.

The managers at the participating unemployment agencies were given the option to either provide us with direct contact information on their employees or forward the survey themselves.4 Twenty-eight managers provided us with contact information on the caseworkers, whereas four managers opted to distribute the survey link to their employees. Using the contact information provided by the managers, we distributed the survey directly to 1911 caseworkers and sent out two reminders over the course of the data collection. A total of 957 of the invited caseworkers (50%) answered all questions necessary for our analysis. We consider this response rate to be satisfactory given the numerous responsibilities and tasks caseworkers perform on a daily basis. In addition, 192 caseworkers participated via open links that were forwarded by their local managers, meaning that our analytical sample consists of 1149 caseworkers.5 Table 3 shows the composition of the sample on key individual-level characteristics. It also shows that the experimental groups balance on the various observables. To determine the minimum detectable effect size given this number of respondents, we have conducted a post-hoc power analysis using G*Power version 3.1. Results indicate an ability to detect a small effect of Cohen's d = 0.17 with a significance criterion of α = 0.05 and power = 0.80 for an independent t-test (two-sided).

| Total | Control | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% women) | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| (0.399) | (0.392) | (0.406) | |

| Age | 47.02 | 46.95 | 47.09 |

| (11.48) | (11.17) | (11.80) | |

| Tenure | 8.72 | 8.64 | 8.82 |

| (7.308) | (7.370) | (7.246) | |

| User-orientation | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.72 |

| (0.171) | (0.168) | (0.174) | |

| Benefit type (% unemployment benefits + cash benefits + job-ready cash welfare benefits) | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| (0.495) | (0.495) | (0.497) |

- Note: means with standard deviations in parentheses. There are no statistically significant differences between experimental groups at the 5% level.

3.4 Measures

To measure caseworkers' willingness to sanction welfare recipients and prioritize them, we used two validated measures from the literature. First, to measure the caseworkers' willingness to sanction, we use a measure previously used by Pedersen et al. (2018). Concretely, we ask the caseworkers following the vignette: “How likely is it that you will sanction Mathias for his absence?” The caseworkers could respond on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“Very unlikely”) to 10 (“Very likely”). For our second measure, we used a measure from Guul et al. (2021) and asked them: “How likely is it that you will exert an additional effort to help Mathias? Assume that an additional effort would mean that you have less time to help other clients.” Again, the caseworkers could reply on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“Very unlikely”) to 10 (“Very likely”). Finally, we tested whether our experimental manipulation worked as intended by asking the caseworkers on the following page: “To what extent do you believe that Mathias is responsible for catching COVID-19?” The caseworkers could reply on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“To a very high extent”).

4 RESULTS

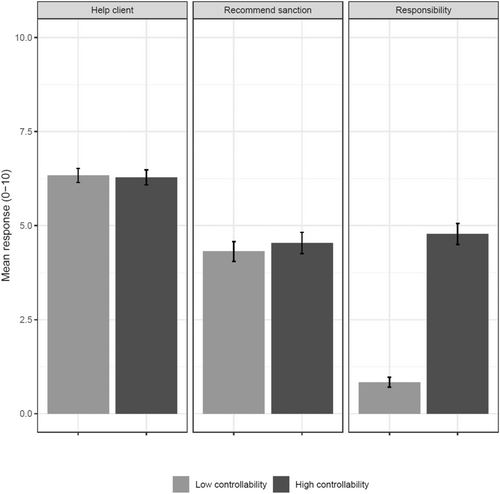

To test our hypotheses, we use OLS analyses with standard errors clustered at the job center level. The results are displayed in Table 4 and Figure 1. Examining the results, we can see that our experiment did successfully manipulate caseworker perceptions of the client's responsibility for getting sick. Thus, we find a significant difference between the caseworkers' attribution of responsibility for the version of the client that got sick with COVID-19 while shopping and the client that got sick at a party. With an average responsibility attribution of 0.8 (shopping) and 4.7 (partying), the caseworkers attribute a little more than five times as much responsibility to the client who got COVID-19 following a party.

| Man. check | Sanction | Help | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 3.94*** | 0.22 | −0.05 |

| (0.17) | (0.16) | (0.12) | |

| Constant | 0.83*** | 4.31*** | 6.33*** |

| (0.07) | (0.13) | (0.08) | |

| N | 1142 | 1152 | 1150 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

However, to our surprise, none of our hypotheses is supported by the data. Hence, we find no statistically significant differences, neither in willingness to help (H1) nor in inclinations to sanction (H2), across our experimental conditions. In terms of willingness to help, the difference between groups is very close to zero, while there is a small yet statistically insignificant difference in the expected direction for inclination to sanction. As can be seen in Table A1, including control variables in the statistical models does not lead to any substantial changes in these results.

4.1 Explorative analyses

The finding of no deservingness effects on caseworkers' help-giving and sanctioning intentions is intriguing, especially in light of the strong effects that were found on respondents' responsibility attributions. Below, we conduct several explorative analyses to (1) address some potential reasons for the lack of a deservingness effect, and (2) look into factors at the individual level that might better predict caseworkers' help-giving and sanctioning intentions or potential moderators of the deservingness effects. However, while these post hoc analyses can give indications of potentially interesting individual-level factors, it is crucial to note that these analyses where not preregistered and, as such, the analyses should be interpreted with caution. Thus, we consider these analyses as hypothesis-generating rather than confirming.

4.1.1 De facto limited discretion?

In order for deservingness cues to have an impact, respondents need to have at least some degree of discretion (and thereby room for variation) in terms of how they respond to the deservingness cues in the vignettes. For instance, even if deservingness cues increased caseworkers' willingness to help or sanction clients in a given situation, their ability to do so may be institutionally constrained (e.g., by formal rules and guidelines or professional norms). If that is the case, there is a risk that our null results are caused by a constrained decision-making process that leaves little room for variation in caseworkers' decisions.

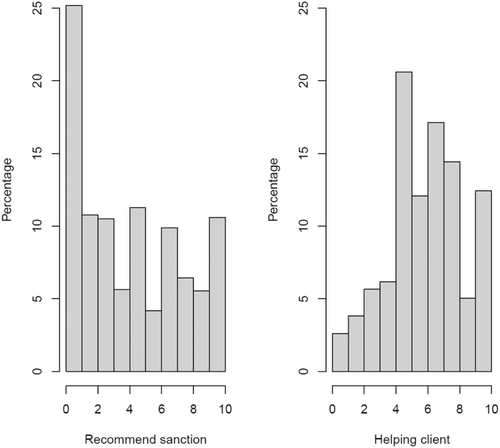

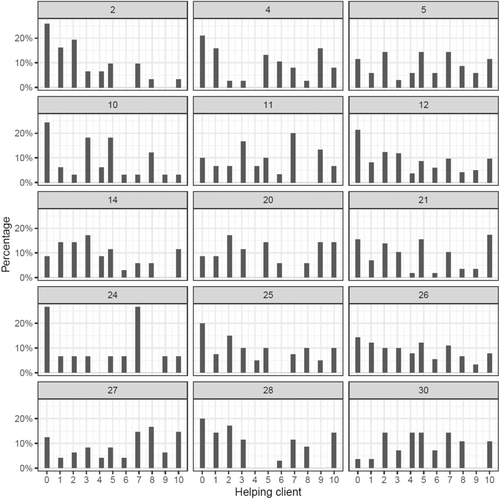

To examine this potential explanation, we investigated the caseworkers' responses on our two dependent variables. Here, Figure 2 shows how the caseworkers' answers are distributed with regard to sanctioning and help-giving intentions. If our null effects were due to a lack of discretion (e.g., regulations dictating that rule breaches like the one in the experimental material should always—or never—be sanctioned), relatively uniform distributions would be expected. However, none of the dependent variables are uniformly distributed. Instead, we observe quite a lot of variation, specifically with regard to the sanctioning variable. Although most respondents (52%) indicated a low intention to sanction (between 0 and 4 on our 0–10 scale), a substantial share (37%) indicated a high intention (between 6 and 10) to sanction, while only 11% opted for a neutral value (5). Moreover, with regard to caseworkers' willingness to exert an additional effort to help the client, we see that 18% of the caseworkers indicated a low likelihood of doing so (between 0 and 4 on our 0–10 scale), 21% chose the neutral value (5), and 61% indicated a high likelihood of exerting an additional effort (between 6 and 10).

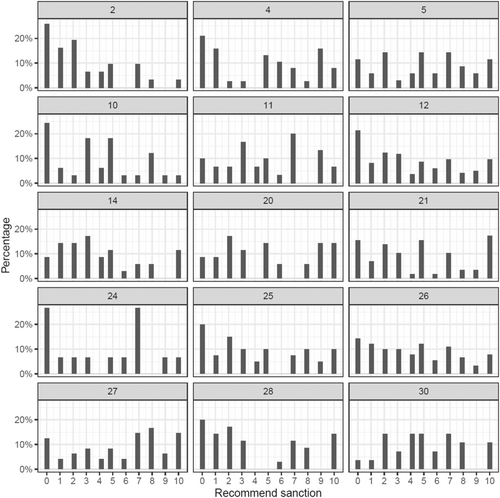

In addition to Figure 2, which is based on our entire sample, in Figures 3 and 4, we show intra-agency distributions for all unemployment agencies where 30 or more caseworkers participated in our survey.6 We do so to address the potential of responses being constrained—not by rules, regulations, and so forth., at the national level (i.e., factors that would have resulted in uniform responses in Figure 2) but by factors at the agency level. It could, for example, be that in some agencies, local norms, instructions from leaders, and the like recommend a strict approach to sanctioning when citizens do not comply with rules, whereas other agencies might adopt a more lenient approach where there is more focus on helping and less on sanctioning. In that case, relatively uniform distributions would be expected when looking within agencies but not necessarily when looking across the entire sample as shown in Figure 2. However, Figures 3 and 4 show high levels of variation on the tendency to sanction and help within the agencies as well. Taken together, our data thus shows that caseworkers' responses on the dependent variables were not uniformly distributed across the entire samples or within agencies, which suggests that our null findings are not a result of caseworkers being constrained by rules, norms, or practices within unemployment agencies.

4.1.2 The role of individual-level factors

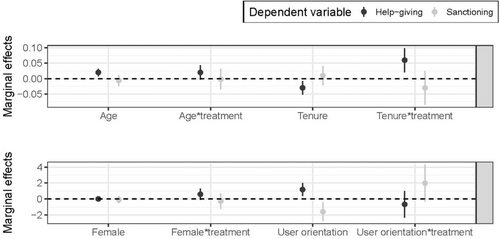

Given that the caseworkers in our experiment did indeed have a high level of discretion—and varied considerably in how they used this discretion in our experiment—it is relevant to explore alternative factors that might potentially explain the caseworkers' decisions to sanction or exert an additional effort given the absence of our hypothesized deservingness effects. Existing literature on street-level bureaucracy has demonstrated how individual-level characteristics can sometimes shape decision-making at the frontline (e.g., Maynard-Moody & Musheno, 2000; Watkins-Hayes, 2011). We therefore conclude our explorative analyses by investigating the potential role of age, tenure, gender, and user orientation. Data on age, tenure, and gender were collected through background questions in the beginning of our survey. Moreover, to measure user orientation, we used four items developed by Andersen et al. (2011) and Gregersen et al. (2021) to measure people's “motivation to deliver public service with the purpose of doing good for the direct user of the service” (Jensen & Andersen, 2015, p. 755).7 We combine the four user-orientation items into an index from 0 to 1 (Cronbach's α = 0.66). Below, in Figure 5, we examine how age, gender, tenure, and user orientation correlate with our dependent variables and potentially moderate the treatment effect.

Looking at Figure 5, it can be seen that age, tenure, and user orientation do seem to be predictive of help-giving intentions among our respondents: Older respondents and respondents with higher levels of user orientation are more willing to help the experimental material's citizen than younger respondents and respondents with lower levels of user orientation. Conversely, tenure is negatively associated with help-giving intentions (controlling for age and gender), indicating that more experienced respondents are less willing to exert additional effort to help the experimental material's citizen compared with their less experienced counterparts. Turning to sanctioning intentions, the explorative analyses indicate that only user orientation is predictive of people's responses, with higher levels of user orientation being associated with lower intentions to sanction. None of the remaining factors (age, gender, and tenure) are significantly related to sanctioning intentions in our data.

We also explored group differences by comparing frontline workers who were most willing to help and least inclined to sanction with frontline workers who were least willing to help and most inclined to sanction.8 Independent t-tests comparing these two groups on age, gender, tenure, and user orientation showed that the group of frontline workers in our data who were most willing to help clients (scoring above the median on willingness to help clients) and least likely to use sanctions (scoring below the median on recommending sanction), were significantly older and scored higher on user orientation (p < 0.05). Thus, these results are generally in line with the results from Figure 5's tests of individual-level differences (for full results regarding group differences, see Tables A6–A8).

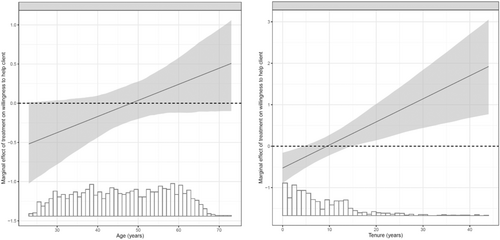

In addition to the direct associations, Figure 5 includes a number of interaction terms to explore indications of moderating effects of personal factors as well. As can be seen, the findings indicate that age and tenure do seem to moderate the impact of our deservingness cue on respondents' help-giving intentions whereas gender and user orientation might not. As can also be seen in Figure 6 below, among the youngest and least experienced respondents, caseworkers do respond as expected with H1 (informing them that the citizen caught COVID-19 at a New Year's celebration does, as expected, make them less willing to exert additional effort to help him compared with if he got infected while grocery shopping). On the contrary, surprisingly, among the oldest and most experienced respondents, people's responses are contrary to our expectations as people become more willing to help the citizen if he caught COVID-19 at a New Year's celebration (compared with if he got infected while grocery shopping). Finally, turning to sanctioning intentions, none of the individual-level factors in Figure 5 moderate the impact of the deservingness cue. In line with the existing literature, our explorative results tentatively suggest that individual-level factors are important for frontline workers' decision-making. Importantly, our explorative results also indicate that the deservingness heuristic (as examined in this study), might work differently depending on the age and user orientation of the caseworker. Here, there may be an important point for future researchers to consider when studying deservingness effects—namely, that deservingness cues may be interpreted or evaluated differently depending on the caseworkers' individual-level characteristics. Again, it is important to emphasize the provisional nature of these exploratory analyses, meaning that the conclusions from this section are tentative and only give indications of potentially important individual-level predictors and moderators.

5 CONCLUDING DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the existing public administration literature on the role of deservingness cues (e.g., Guul et al., 2021; Jilke & Tummers, 2018; Pedersen et al., 2018) by examining whether health-related deservingness cues shape attitudes and behavior of frontline workers towards citizens in need of government benefits. We examined through a vignette experiment whether caseworkers in Danish unemployment agencies are more likely to punish unemployed welfare recipients if they are responsible for their own sickness.

The findings suggest that frontline workers attribute more responsibility to welfare recipients for their sickness if they got sick due to irresponsible behavior. However, contrary to our hypotheses, the treatment does not influence frontline workers' inclination to help or sanction clients. Thus, even though frontline workers are more likely to attribute responsibility for sickness to clients who engaged in irresponsible behavior, this does not necessarily lead to more sanctioning or less help towards these welfare recipients. These results are surprising given the extensive literature on how deservingness perceptions strongly influence attitudes and behavior among different groups of individuals, including citizens, frontline workers, and politicians (Aarøe et al., 2021; Aarøe & Petersen, 2014; Baekgaard et al., 2021; Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Jilke & Tummers, 2018; van Oorschot, 2006). Our findings are particularly surprising, given how the manipulation check showed that the treatment clearly affected the caseworkers' perceptions of the client's responsibility. While our hypotheses are based on how people generally react to deservingness cues, frontline workers might have specific motivations that are distinct from the motivation of the general public. According to Zacka (2017) frontline workers adopt different moral dispositions in citizen-state interactions, which might influence how they approach clients and therefore also their decision-making. Thus, one theoretical explanation for the null results could be the vignette describing a “deserving” client. If that is the case, this may induce the frontline worker to adopt a moral disposition of a “caregiver,” who gives attention to clients they sympathize with, while the vignette describing the “undeserving” client made frontline workers respond as an “enforcer,” who gives more attention to undeserving clients (see Zacka, 2017).

In a series of exploratory post hoc analyses, we show that the lack of treatment effects cannot be explained by external constraints to people's responses (neither national-level nor agency-level constraints). Thus, we find considerable variation on the outcomes both across the sample of frontline workers and within each unemployment agency. In addition, explorative analyses indicate that decision-making among frontline workers is shaped by individual factors such as age, tenure, and user orientation rather than deservingness cues. These results speak to the broader literature on the individual-level factors shaping frontline workers' willingness to help welfare clients and their general tolerance for administrative burdens (Bell et al., 2021; Halling et al., 2023). Yet, the individual-level explorative analysis also indicates that the deservingness treatment is effective in influencing the tendency to help citizens among the youngest caseworkers and those with the least experience. It is important to note, however, that these analyses are explorative, and we consider them as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Thus, future research is warranted to replicate and validate these findings in a more preplanned manner. In sum, the results suggest that frontline workers, at least in our sample, may be less influenced by deservingness considerations than previously thought and that other individual-level factors may potentially play a larger role in shaping their attitudes and behavior.

Another potential reason for the lack of treatment effects could be due to limitations regarding our design, case, and the general context of the study. First, we do not know the extent to which the estimates from our survey experiment travel to a real-world context. On the one hand, we could expect that our estimates are conservative because frontline workers in a real-world situation work under a considerable workload, which might make them rely more on deservingness cues in their decision-making. On the other hand, we might find weaker estimates in a real-world situation given that real outcomes are at stake, which could potentially make frontline workers base their decisions on more thorough considerations (and less on intuitively derived deservingness-perceptions). Second, one may speculate that the lack of differences in caseworkers' willingness to help and sanction clients based on our deservingness cue might be because of COVID-19 being a special case. In a Danish context, at least, it was repeatedly communicated by the government and health authorities that multiple lockdowns and strict regulations were needed because “one death due to COVID-19 is one too many.” This might have created a strong general conviction that nobody should be worse off due to contracting COVID-19. Therefore, it is important that future research extend the findings to other service areas and in relation to health-related deservingness cues that are not associated with COVID-19.

Relatedly, future research should investigate whether responsibility cues impact decision-making when using an even stronger treatment of responsibility. Even though the frontline workers in this study attributed responsibility for catching COVID-19 in line with the treatment, they might not have attributed responsibility in terms of actively seeking out COVID-19. Thus, future studies should test whether frontline workers' reactions are influenced by a stronger treatment with more distinct conditions of deliberately risky behavior and completely unavoidable exposure, respectively.

Moreover, while the sickness-related issue in our experiment did not influence the behavior of frontline workers, we do not know for certain whether the findings generalize to other client groups, sectors, or decision scenarios. For example, we might get different results if frontline workers are asked to compare two clients in terms of help-giving and sanctioning (e.g., Jilke & Tummers, 2018). Future research should continue to examine the generalizability regarding the role of sickness-related cues for frontline workers' decision-making. Such studies would help with clarify whether this article's null finding is a potential or a more conclusive limitation to the deservingness heuristic.

Finally, a more general alternative explanation is whether deservingness cues related to one domain (e.g., health) influence decision-making in another domain (e.g., unemployment). This article tests the effect of deservingness cues related to sickness on frontline workers' attitudes and behavior related to unemployment. Thus, we might have found support for our theoretical expectations if frontline workers had, for instance, been asked about their prioritization of who should receive intensive care because it also relates to the health domain. Even though frontline workers working with health (e.g., doctors) might have stronger professional norms that could crowd out the effect of deservingness, future studies could explore such research questions. In conclusion, our results show that the deservingness heuristic may have limits in guiding frontline workers' attitudes and behavior towards welfare recipients. As welfare recipients often face health-related challenges, it is crucial for policymakers and public administrators to be aware of how deservingness cues impact frontline workers' behavior towards citizens in need of government benefits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Asdija Thangaratnam and Signe Sandager for providing excellent assistance with the data collection. We also thank Rasmus Vedel Jensen for his seminar paper that gave us the idea for this research.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement number 802244).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

APPENDIX A

| Sanction | Help | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0.25 | −0.02 |

| (0.19) | (0.12) | |

| Female | −0.11 | 0.08 |

| (0.28) | (0.24) | |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.03*** |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Tenure | −0.01 | −0.27* |

| (0.02) | (0.01) | |

| Constant | 4.46*** | 5.24*** |

| (0.64) | (0.47) | |

| N | 1068 | 1067 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

| Model | Help | Sanction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treatment | −0.03 (0.13) | −1.01* (0.46) | 0.21 (0.16) | 0.29 (1.07) |

| Age | 0.02** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.02) |

| Treatment × Age | 0.02* (0.01) | −0.00 (0.02) | ||

| Constant | 5.43*** (0.34) | 5.92*** (0.50) | 4.58*** (0.42) | 4.54*** (0.67) |

| Observations | 1129 | 1129 | 1131 | 1131 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

| Model | Help | Sanction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treatment | −0.07 (0.12) | −0.54 (0.27) | 0.22 (0.17) | 0.43 (0.34) |

| Female | 0.01 (0.18) | −0.29 (0.31) | −0.08 (0.25) | 0.06 (0.36) |

| Treatment × Female | 0.59 (0.34) | −0.27 (0.42) | ||

| Constant | 6.34*** (0.15) | 6.58*** (0.24) | 4.37*** (0.26) | 4.26*** (0.35) |

| Observations | 1137 | 1137 | 1139 | 1139 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

| Model | Help | Sanction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treatment | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.51* (0.19) | 0.25 (0.20) | 0.54 (0.30) |

| Tenure | −0.03* (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| Age | 0.03** (0.01) | 0.03** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Female | 0.08 (0.24) | 0.06 (0.24) | −0.11 (0.28) | −0.10 (0.27) |

| Treatment × Tenure | 0.06** (0.02) | −0.03 (0.03) | ||

| Constant | 5.24*** (0.47) | 5.50*** (0.50) | 4.46*** (0.64) | 4.31*** (0.61) |

| Observations | 1067 | 1067 | 1068 | 1068 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05..

| Model | Help | Sanction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Treatment | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.52 (0.52) | 0.22 (0.21) | −1.23 (0.84) |

| User orientation | 1.18** (0.41) | 1.52* (0.56) | −1.59** (0.56) | −2.57*** (0.59) |

| Tenure | −0.02* (0.01) | −0.02* (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Age | 0.03** (0.01) | 0.03** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Female | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.05 (0.23) | −0.12 (0.28) | −0.11 (0.28) |

| Treatment × User orientation | −0.68 (0.68) | 1.99 (1.13) | ||

| Constant | 4.38*** (0.47) | 4.13*** (0.51) | 5.61*** (0.81) | 6.34*** (0.83) |

| Observations | 1045 | 1045 | 1046 | 1046 |

- Note: Clustered standard errors at the municipality level in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

| Variable | Help | Sanction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50% percentile | >50% percentile | Diff. | ≤50% percentile | >50% percentile | Diff. | |

| Gender | 0.80 (0.40) | 0.81 (0.39) | −0.01 | 0.81 (0.39) | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.02 |

| Age | 45.77 (11.85) | 48.34 (10.94) | −2.57*** | 47.23 (11.24) | 46.75 (11.76) | 0.48 |

| Tenure | 8.83 (7.30) | 8.63 (7.33) | 0.20 | 8.55 (7.05) | 8.90 (7.56) | −0.35 |

| User orientation | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.74 (0.18) | −0.03** | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.71 (0.17) | 0.03*** |

- Note: Two-sided t-tests. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

| Variable | Help | Sanction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤25% percentile | ≥75% percentile | Diff. | ≤25% percentile | ≥75% percentile | Diff. | |

| Gender | 0.79 (0.40) | 0.80 (0.40) | −0.01 | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.80 (0.40) | −0.01 |

| Age | 45.68 (11.94) | 48.70 (10.95) | −3.02*** | 47.20 (11.29) | 46.72 (11.66) | 0.48 |

| Tenure | 8.95 (7.42) | 8.79 (7.40) | 0.16 | 8.44 (7.43) | 8.91 (7.34) | 0.47 |

| User orientation | 0.70 (0.17) | 0.74 (0.19) | −0.04** | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.03** |

- Note: Two-sided t-tests. ***p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

| Variable | Help and sanction | Diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High willingness to help + low willingness to sanction | Low willingness to help + high willingness to sanction | ||

| Gender | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.003 |

| Age | 48.41 (10.80) | 44.61 (11.69) | 3.80** |

| Tenure | 8.19 (7.48) | 8.82 (7.26) | −0.63 |

| User orientation | 0.75 (0.19) | 0.70 (0.16) | 0.05* |

- Note: Two-sided t-tests. High willingness to help is defined as at or above the 75% percentile on the willingness to help measure, while low willingness to help is defined as at or below the 25% percentile. High willingness to sanction is defined as at or above the 75% percentile on willingness to sanction, while low willingness to sanction is defined as at or below the 25% percentile. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data and materials to reproduce the main analyses are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BWYGKL. The preregistration is available at: https://osf.io/5z48w/?view_only=00757069dfa043e78353150e13cb6f47.