Weight stigma experienced by patients with obesity in healthcare settings: A qualitative evidence synthesis

Summary

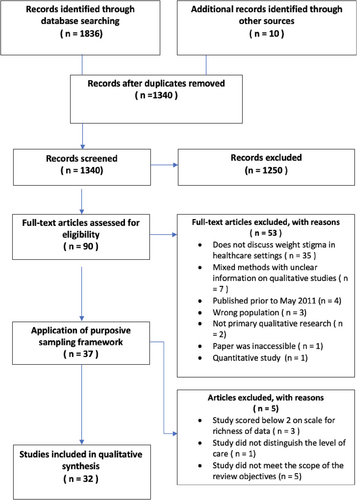

Weight stigma research is largely focused on quantifiable outcomes with inadequate representation of the perspectives of those that are affected by it. This study offers a comprehensive systematic review and synthesis of weight stigma experienced in healthcare settings, from the perspective of patients living with obesity. A total of 1340 studies was screened, of which 32 were included in the final synthesis. Thematic synthesis generated three overarching analytical themes: (1) verbal and non-verbal communication of stigma, (2) weight stigma impacts the provision of care, and (3) weight stigma and systemic barriers to healthcare. The first theme relates to the communication of weight stigma perceived by patients within patient–provider interactions. The second theme describes the patients' perceptions of how weight stigma impacts upon care provision. The third theme highlighted the perceived systemic barriers faced by patients when negotiating the healthcare system. Patient suggestions to reduce weight stigma in healthcare settings are also presented. Weight stigma experienced within interpersonal interactions migrates to the provision of care, mediates gaining equitable access to services, and perpetuates a poor systemic infrastructure to support the needs of patients with obesity. A non-collaborative approach to practice and treatment renders patients feeling they have no control over their own healthcare requirements.

1 INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a chronic relapsing disease typified by the accumulation of excess adiposity,1 which is associated with acute health burdens including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and premature mortality.2 According to the World Health Organization,1 the risk of comorbidities associated with obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2) increases with BMI. However, research has shown that the widespread stigma and discrimination experienced by those living with obesity is a stronger predictor of poor health outcomes than BMI.3, 4

Weight bias and weight stigma are interrelated concepts, but there are differences between the two. Weight bias is described as having negative beliefs and attitudes toward people living with overweight and obesity.5 It is theoretically understood as originating from false and negative attributions around the causality and controllability of weight.5 Weight stigma is instigated by weight bias, facilitated by societal norms and manifested through actions that can be exclusionary and discriminatory resulting in the devaluation and marginalization of people living with obesity.6

Weight stigma is prevalent across healthcare settings7 where it has been consistently shown to contribute to poor physical health outcomes and the maintenance of obesity via physiological8 cognitive, emotional, and behavioral pathways.3, 9 In addition to physical ill health, weight stigma is associated with poor psychosocial outcomes10 and an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality.11 A scoping review on the effects of weight bias experienced by patients in primary healthcare settings found that enacted weight stigma influenced patients' expectation of differential healthcare treatment,12 which negatively impacted upon healthcare utilization, ultimately contributing to poor health outcomes. Further research has highlighted that perceived weight stigma experienced in healthcare settings is a barrier to both the prescription and uptake of alternative interventions to lifestyle interventions such as medications and metabolic surgery.13

Weight stigma research has largely been focused on quantifiable outcomes7, 14, 15 with inadequate representation of the perspectives of those that are most affected by it.16 This can lead to a misrepresentation of the phenomenon under review. Qualitative studies that capture the experience of weight stigma from the patient perspective can increase awareness of how stigma presents within patient–provider interactions and ultimately inspire change in healthcare provision. Previous reviews conducted from the patient perspective have primarily concentrated on the views and experiences of weight management17 as well as the outcomes of bariatric surgery.18 More recently, a review has reported on the lived experiences of people living with obesity, discussing concerns regarding the health risks associated with obesity and patient aspirations for future obesity treatment.19 To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first review to systematically search for and synthesize weight stigma experienced in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings, explicitly from the patient perspective.

The aim of this review was to explore weight stigma experienced across healthcare settings, from the perspective of the patient with obesity to gain a deep and broad understanding of the barriers to treatment that arise in this cohort. A further objective of the current review was to collect the patients' suggestions on how to minimize weight stigma in healthcare settings to inform best practice and future intervention design.14

2 METHODS

The review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews on September 12, 2021 (CRD42021273286). The reporting of this qualitative evidence synthesis was guided by the ENTREQ checklist20 and PRISMA guidelines.21 A comprehensive overview of the methodology can be found in the peer-reviewed protocol.22

2.1 Information sources and search strategy

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with an information specialist (RD). The search terms were refined using a combination of MeSH terms, free-text terms, and methodological filters to capture the constructs under review (Table 1). Electronic searches were conducted in five databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase, and Scopus. To facilitate a comprehensive search, gray literature searches were preformed (PsycExtra and Google Scholar). Forward and backward citation chaining and hand searches of the reference lists of the included studies were also conducted. Where eligible studies were not easily accessible, key authors were contacted to obtain the full-text papers. Studies that were not retrieved within the pre-defined 2-week deadline were omitted from the synthesis.

| ((((((((weight stigma) OR (weight prejudice)) OR (weight-based discrimination)) OR (fat shame*)) OR (fat shaming)) OR (obese* stigma)) OR (obesity* stigma)) OR (anti-fat)) AND ((((((((((interview) OR (“interview as topic”)) OR (experience*)) OR (experiences)) OR (personal narrative)) OR (biography*)) OR (“biographies as topic”)) OR (narrative*)) OR (narration*)) OR (qualitative)) |

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined using the PICoS tool23 (Table 2). Studies that collected and reported primary qualitative data exploring the perceptions and experiences of enacted weight stigma across primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings from the perspective of the patient living with obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) were eligible for inclusion. Mixed method studies were included where qualitative data were collected and the qualitative findings were reported separately to the quantitative results. There were no geographical restrictions placed on searches; however, eligible studies were required to identify the level of care provision to satisfy the inclusion criteria. Studies that did not identify the level of care provision were excluded from the synthesis. All studies retrieved in English and published after May 2011 were considered for inclusion in the review. Further information related to the coverage dates can be found in the protocol.22

| PICoS |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Patients living with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) Adults (18 years of age or older) |

Patients that do not live with obesity Adolescents and children will not be included (<18 years of age). |

| Phenomenon of interest | Patients' perceptions and experiences of weight-based stigma enacted by healthcare professionals | The experiences of enacted weight-based stigma from a person living with obesity outside of primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings |

| Context | Primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings. All geographical locations | Non-clinical settings |

| Study type | Primary qualitative research. Mixed methods studies will be considered for review where the data has been collected and analyzed using qualitative methods and the findings are reported separately to the quantitative results. |

Studies that employ quantitative methods only Studies published prior to May 2011 Studies not published in English |

2.3 Study screening methods

Database search results (1848) were imported into Endnote X20 where duplicates were retrieved and removed. The remaining 1340 studies were exported into the Rayyan data screening tool where title and abstract screening was conducted by two independent reviewers (LR and RC). Any disagreements in judgment were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (CH). Ninety full text articles were screened by two independent reviewers (LR and RC) in accordance with the eligibility criteria (Table 2). Any disagreements in judgment were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (CH). Eligible studies identified through forward and backward citation searches were screened by one reviewer (LR). A second independent reviewer (RC) screened a random 20%, and any disagreements were discussed until consensus was achieved.

2.4 Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers (LR and RC) using a modified data extraction form in Microsoft Excel. The following data were recorded: citation, geographical location, study setting, participant characteristics, recruitment strategy, data collection method, data analysis approach, themes identified in the study, data extracts related to the themes, author interpretations of the themes, recommendations made by the author(s), recommendations made by the patient(s), and limitations of the study. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist.24 The appraisal was conducted by two independent reviewers, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third member of the review team.

2.5 Analysis and synthesis

A qualitative inductive approach following the steps outlined by Thomas and Harden25 was used to collate and synthesize the data from the included studies. This method of analysis is useful for integrating the findings of multiple qualitative studies while retaining the integrity of the original study findings. In line with the Thomas and Harden approach, primary qualitative data and author interpretations were extracted from the included studies and imported into Nvivo 20 software for qualitative analysis. The process initiated with the line-by-line coding of the included data into free codes to facilitate the translation of concepts across the included studies. The next stage of analysis involved the organizing and grouping of the free codes into descriptive themes. In the final step, the descriptive themes were analyzed in light of the review question to generate new interpretations and the development of analytical themes that accounted for patterns that became evident across the included studies. The analysis was completed by one independent reviewer (LR) in consultation with the review team at each step of the analysis. This was an iterative process that produced the results presented below.

2.6 Reflexivity

Reflexivity is an essential aspect of qualitative research that involves acknowledging how the author(s) personal stance and beliefs related to the phenomenon being explored may influence the design of the study, data gathering, data analysis, and the interpretation of the findings.26 The review team is composed of authors with backgrounds in patient advocacy (SB), medicine (MC), information science (RD), computer science (OC), and four psychologists (LR, RC, CH, and JW), two of whom have subject-area expertise (LR and CH) and expertise in qualitative research (CH). The incorporation of different perspectives on the review team was sought to enhance reflexivity by cultivating a practice of constant comparison during the analytic process to ensure that the interpretations of only one author were not privileged in the reporting of the findings. Team members considered their positionality and beliefs related to the phenomenon under review. The lead author (LR) documented any preconceptions that arose in a reflexive journal and in collaboration with the review team, critically reflected on and accounted for them at each stage of the analysis.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study characteristics and quality appraisal

A total of 1340 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility for inclusion in the synthesis. Of these, 90 full-text articles were screened, of which 37 were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review. A three-step sampling framework27 composed of three key sampling criteria specific to the review objectives (Supporting Information S1) was generated and applied to the identified 37 eligible studies. All of the studies originally included, but not sampled, and the reason for their exclusion can be found in Table 2 in Supporting Information S1. After applying the sampling framework, 32 studies that met the review inclusion criteria (Table 1) were included in the synthesis (Figure 1). These studies explored the subjective experiences of weight stigma of 1384 adults in studies conducted across primary (10), secondary (14), and tertiary (10) healthcare settings.

Of the 29 studies that reported gender, 3% (32/1104) of the participants identified as male. Studies were included from a range of countries: Australia (3), Canada (5), Denmark (2), Ireland (1), New Zealand (3), Norway (1), Spain (1), Sweden (2), the United Kingdom (3), and the United States (11). Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Overall, the included studies were found to be of good quality (mean CASP score 9/10; Table 3). Quality scores ranged from 7.5 to 10 (Table 1 in Supporting Information S2). Two studies did not report ethical approval28, 38; 16 studies did not discuss researcher reflexivity; one study scored 7.5 due to ambiguity in the reporting of the study aims, no clear statement of findings, no ethics reported, and no discussion of reflexivity.38 A sensitivity analysis determined that the study findings contributed meaningful primary data to the synthesis; thus, the study was not excluded.

| Citation | Sample size (N) | Country | Setting (level of care) | Study aim(s) relevant to this analysis | Recruitment strategy | Data collection method | Data analysis approach | Quality score (CASP checklist) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akoury et al.29 | 15 | USA | Mental health clinic and private practices – secondary | To examine the experiences of weight-based discrimination in therapy | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Bombak et al.30 | 24 | Canada | Reproductive healthcare – secondary | To explore the experiences of women with obesity in reproductive healthcare settings | Purposive and snowball sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis filtered through Foucaultian theory | 9 (strong) |

| Buxton and Snethen31 | 26 | USA | Primary care | To describe female experiences and perceptions of stigma in primary healthcare settings | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Phenomenological approach (Colaizzi method) | 9.5 (strong) |

| Christenson et al.32 | 17 | Sweden | Maternal healthcare – secondary | To explore important aspects of good and successful gestational weight management | Purposive sampling | Focus groups and interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Cusimano et al.33 | 15 | Canada | Tertiary care setting | To explore the experiences of women with low-grade endometrial cancer and severe obesity as they navigate the healthcare system | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 8.5 (moderate) |

| Davis and Bowman34 | 20 | USA | Bariatric care – tertiary | To explore the subjective experiences and daily struggles that individuals potentially face due to weight-related oppression | Convenience sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Grounded theory approach (Birks & Mills, 2011) | 9 (strong) |

| DeJoy et al.35 | 36 | USA | Maternal healthcare – secondary healthcare setting | To understand the experiences of women with obesity in the US maternity system | Purposive sampling strategy | Demographic graphic survey and interviews (semi-structured) | Phenomenological analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Dieterich et al.36 | 18 | USA | Perinatal healthcare – secondary | Exploration the impact of perceived weight stigma on the breastfeeding experiences. | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Content analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Gailey37 | 74 | USA | Primary care | To explore hyper (in)visibility as a result of symbolic violence toward women living with obesity | Purposive sampling | Interviews (open-ended questions) | Grounded theory (Glasser & Strauss, 1967) | 9.5 (strong) |

| Geddis-Regan et al.38 | 8 | UK | Bariatric healthcare – tertiary | To explore the experiences of patients and dentists regarding referral to bariatric dental care facilities | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Heslehurst et al.39 | 15 | UK | Maternity care – secondary | To explore women's lived experiences being pregnant with obesity | Purposive sampling | Interviews (low-structured) | Thematic content analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Hurst et al.40 | 30 | USA | Prenatal care – secondary | Identify ways to improve the quality of care for pregnant women with obesity receiving perinatal care | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 8 (moderate) |

| Incollingo Rodriquez et al.41 | 501 | USA | Maternity care – secondary | To examine the prevalence and frequency of weight-stigmatizing experiences in prenatal and postpartum healthcare | Purposive sampling | Mixed method | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Jarvie42 | 27 | UK | Diabetic antenatal clinic – secondary | To explore the lived experience of women with co-occurring maternal obesity and GDM during pregnancy and post birth period (<3 months) | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Corss sectional thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Jiménez-Laoisa et al.43 | 9 | Spain | Primary and tertiary healthcare settings | To explore women with obesity' experiences of weight stigma in healthcare settings | N/A | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis from a latent and constructionist perspective | 7.5 (weak) |

| LaMaare et al.44 | 17 | New Zealand | Reproductive healthcare – secondary | To explore the experiences of overweight and obese women/trans women in fertility/pregnancy care | Snowball sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Lauridsen et al.45 | 21 | Denmark | Prenatal care setting – secondary | To explore stigmatization women may have experienced during interventions | Convenience sample | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Lindhardt et al.46 | 16 | Denmark | Specialist antenatal care – tertiary care | To describe the experiences of pregnant women with a pre-pregnant BMI > 30 kg/m2 during their interactions with HCP | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis – Giorgi's phenomenological approach | 9 (strong) |

| Malik et al.47 | 40 | Australia | Dental services – primary care | To understand locally relevant barriers to dental services so to improve widespread dental access for PwCSO | Purposive sampling | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| McPhail et al.48 | 24 | Canada | Reproductive healthcare – secondary | To explore the experiences of obesity stigma experienced by women in reproductive care settings | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Melander et al.49 | 14 | Sweden | Primary care | To describe women's experience of living with lipedema | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Qualitative content analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Meleo-Erwin50 | 217 | USA | Post-operative bariatric healthcare – tertiary | To explore patient understanding of how bariatric clinics either facilitate or pose barriers to positive outcomes and how this may influence attendance to follow up care | Convenience sample | Analysis of posts (n = 50) and comments (n = 167) | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Nagpal et al.51 | 9 | Canada | High-risk obstetrics clinic – tertiary care | To identify and present suggestions from the women's perspective that may inform the reduction of weight stigma in prenatal clinical settings | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Content analysis | 9 (strong) |

| O'Donoghue et al.52 | 15 | Ireland | Primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings | To explore the lived experience of weight stigma in healthcare settings from the perspective of patients living with obesity | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Framework analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Paine53 | 50 | USA | LQBTQ+ primary care services | Explore the experiences of LQBTQ people of weight stigma in healthcare | N/A | Interviews (semi-structured) | Abductive analytic approach – not specified | 8 (moderate) |

| Parker54 | 27 | New Zealand | Maternity care setting – secondary | Explore the experience of women with obesity navigating the healthcare system | Self-identified and purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Rand et al.55 | 15 | Canada | Weight management setting – tertiary | Explore how do those living with obesity describe their experiences with psychological, emotional, and social well-being issues | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Raves et al.56 | 35 | USA | Bariatric healthcare – tertiary | Explore the relationship between weight stigma and bariatric surgery outcomes from the perspective of the patient and provider. | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) and patient observation ongoing over 4 years. | Ethnographic analysis | 9 (strong) |

| Russell and Carryer57 | 8 | New Zealand | Primary care | To explore large bodied women's experience of accessing New Zealand-based general practice services | Snowball sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Setchell et al.58 | 15 | Australia | Primary care | An exploration of patients' perceptions of interactions with physiotherapists that involved weight. | Convenience sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Thematic analysis | 10 (strong) |

| Thorbjornsdottir et al.59 | 10 | Norway | Maternity care – secondary | To explore women with obesity' experiences of childbirth and their encounters with birth attendants | Convenience sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Descriptive phenomenological approach | 10 (strong) |

| Williams60 | 16 | Australia | Primary care | To explore and interpret women with obesity' understanding of their individual health experiences | Purposive sampling | Interviews (semi-structured) | Grounded theory | 9 (strong) |

3.2 Qualitative evidence synthesis results

Three inter-connected overarching analytical themes were identified: (1) verbal and non-verbal communication of stigma, (2) weight stigma impacts the provision of care, and (3) weight stigma and systemic barriers to healthcare. The first theme relates to the verbal and non-verbal communication of weight stigma perceived by patients with obesity within patient–provider interactions. The second theme pointed to the patients' perceptions of how weight stigma impacts the provision of care for obesity. The third theme highlighted the perceived systemic barriers faced by patients with obesity trying to negotiate the healthcare system. Patient suggestions to reduce weight stigma in healthcare settings were also collected and are reported below: “See me as a person first.” The GRADE CERQual assessment28 was applied to the analytical themes and the supporting themes to evaluate confidence in the review findings. Of the eight findings, six were graded as high confidence, and two were graded as moderate confidence; the results can be found in Supporting Information S3.

3.3 Theme 1: Verbal and non-verbal communication of weight stigma

Patients felt devalued through repeated negative interactions with healthcare providers where the use of derogatory language38, 29-35, 37, 39-56, 59, 60 and pejorative non-verbal behaviours29-35, 37, 39-55, 59, 60, 36, 57 were perceived to convey weight stigma across primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings. The patient–provider relationship was the primary source of conflict across the literature. Experiencing depreciating comments,38, 29-35, 37, 39-56, 59, 60 not being listened to,29, 31, 32, 39-41, 43, 46, 48, 51, 54, 36, 57 and being “talked down to”29-32, 34, 35, 39, 41, 45, 46, 48, 50-53, 57 were prevalent experiences for patients with obesity. Overall, the patients in the included studies described feeling disempowered when trying to negotiate their healthcare requirements.

3.3.1 Disrespectful dialogue

I thought maybe I was having some kind of neck problem because I worked in a factory. And so I said, “Well, what is that?”. And he[GP] said, … “That's fat. You just love the pork, don't you?”56

I basically got a lecture every time I went in. They made judgements about what I ate, about how much I exercised. They never asked me; they just said things like “Don't drink soda,” which I don't, and “Don't eat candy bars,” which I don't.35

It was a totally different experience the first time I came to [Tertiary care], I was listened to, the doctor looked straight at me and I actually felt what I had to say mattered.52

My fourth pregnancy was twins and I lost one of the babies and the consultant put everything that went wrong down to my weight, even losing the baby.52

3.3.2 Non-verbal cues

Does he give you pap smears: G: No, uh-uh. He also doesn't examine me … And I think it has to do with my weight … I'm under the impression like he would prefer not to … touch me.30

I feel my doctor is looking at the computer and making faces. I sometimes want to say why are you making that face? Just say what you have to say.52

No-one is completely rude, it is much subtler than that, it's the facial expressions when you walk into the room first – no eye contact.52

I still wanted to talk to [GP] about something else but [GP] got up and walked to the door and stood there like it was time for me to leave. [GP] needed to listen to me and reassure my fears.57

Health care providers shock you when they use words like “morbidly obese.” And I think they believe using words like that will shock you into thinking, “Oh, I need to lose weight,” and that's not what happens.51

…because you cannot scare away a weight problem. It is not a good method! It doesn't work! Unfortunately! Or else we would have been very thin. (laughs) […]I have met doctors who lectured me and made me go home and cry afterwards. It has never worked to frighten someone to lose weight. It only adds to your anxiety and worries and often has the opposite effect somehow.32

I get upset I comfort eat, and the thing is when you get upset at appointments because they say about BMI, you go and comfort eat.42

3.4 Theme 2: Weight stigma impacts the provision of care

This theme represents the patients with obesity perceived loss of agency in seeking treatment options and gaining equitable access to suitable healthcare services. Patients reported that the provision of care oscillated between the dismissal of non-weight-related concerns33, 35, 37, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 36, 57 in active presentations of ailment to the catastrophizing of potential risks30, 35, 40-44, 46, 48, 51, 59 associated with higher weight in preventative care. Patients report procedures being put upon them or being refused access to care based on potential risk in the absence of investigating the patients' unique presentation. A non-collaborative approach to care delivery rendered patients feeling vulnerable,35, 47, 49, 52, 54, 60 scared,30, 32, 35, 42, 48, 59 and feeling discriminated against.33, 41, 44, 51, 55

3.4.1 Dismissed, referred, and refused

“You know, you go in there, I got a headache.” “It's because you're fat.” “My toes hurt.” “It's because you're fat.”56

I had my 1 week post op appt. and he was again very late, checking his texts while with me. And I have had a couple of concerns post-surgery, heart palpitations and pain under my ribs, and his coordinator said merely to speak to your primary care physician and cardiologist if you are concerned.50

It was initially, I was deemed as kind of high maintenance at the start and did find it difficult to find a midwife. When I'd phone around and they'd ask me the simple questions and I'd say well I'm a bigger girl, “oh well that's going to take a bit more attention so I don't have the space for you now”54

3.4.2 Reduced to a metric

The GP weighed me and measured my BMI without even speaking to me about it. Then I am referred to a special practice for fat pregnant women without my consent. I really feel stigmatized. It is quite all right to speak about smoking but why can they not address the obesity as it is. I am much more upset now than if he had told me up front. I'm going to confront him next time I see him.46

I had had an IUD placed. And I wanted to have it out, and [my doctor] refused. She said that at my weight, it would be a disaster if I got pregnant. … So it was probably a year of me going and saying “I really want to take this out.” And, her just saying “Absolutely not.” … So I called Planned Parenthood one day. I went there, to get it out. And I was crying. I went into that appointment thinking that I was going to have another doctor tell me that I shouldn't do it and I must be crazy. … And she realized I was crying and she said “You know, are you okay?” And I said “Well, you know, I'm just, I want to have a baby.” And I was lying down, and I figured “Maybe she can't tell that I'm four hundred pounds.” And she came up by me, and she said “Of course you want to have a baby. What's wrong?” And I said “Well, my doctor wouldn't take this out.” She said “Okay. What am I missing?” I said “What do you mean?” She said “Well, what's your health, like, high blood pressure?” I said “No.” “How's your blood sugar?” I said “Pristine.” … And she said “Do you smoke?” I said “No.” And she was like, “Of course, you've got every right in the world to want this.” And she was rubbing my arm and that made me cry harder. And she took it out.48

[My primary care office] prints out these reports and it tells you your BMI on it. And it's like, how is that number even relevant to my health care and the reason for my visit. That number, BMI, is almost like a standardized test in high school or something, where the visit just becomes all about this number.36

3.5 Theme 3: Weight stigma and systemic barriers to healthcare

3.5.1 Lack of consistency in the delivery of care

I cannot find a doctor willing to take on my care for this. I am near [location] and would like to know if there are any doctors near me who can do this. My primary care practitioner does not feel comfortable as he is not knowledgeable about this procedure. I have not had any follow up labs related to this surgery since. I recently found out I have severe iron deficient anaemia that I am being treated with blood and iron infusions. The haematologist who is treating me does not want/or is not aware of the other things I need to be tested for. From what I'm gathering most surgeons require follow-up care and yearly labs and they check for a lot more than what I have mentioned. I have tried to contact a few bariatric surgeons near me but none are willing to take on my after care. I'm really worried that since I am so iron deficient that I may be deficient in other things too.50

I don't want any extra special treatment; it should just be the case that if you are a patient you can access the care you need.38

It would be great to receive the same kind of treatment as a patient with cancer. Because they have someone laying it out nicely, they get treatment plans, they receive help. We are often met by “Ok, this is a routine check-up and you can book another appointment later when you'd like to come back.” There is never a treatment plan whatsoever.32

3.5.2 Update the outdated advice

They don't tell you what diet to have, how to exercise, how to lose the weight properly, or what foods to stay away from. They just tell you to lose weight.51

Now, for example, I have been operated on and I have been controlling my diet since May … but I have stagnated and there is no way to lose weight. And the last time I went to the surgeon, he told me: “You have to do more exercise or eat less.” Well, I'm going to drink only water, because I'm eating only protein shakes and there's no way, I don't know. The only thing they [the doctors] tell you is “get on a diet.” They should get involved a little bit more ….43

Yeah so they've kinda, they're saying you can't birth at [birth centre] and that your weight's a problem but they're not offering you anything, they're not explaining to you why and they're not offering you anything to do about it.54

3.6 Patients suggestions: “See me as a person first”

I wish my doctor would see me as a person first, who has feelings. Not just as fat. If only he would ask me questions, try to understand how I got here. It's not just black and white, it is way more complex than that.52

I'm a human and I want someone to understand me and listen to me. I want to communicate to him about my concerns and him to treat me with respect and to treat me like a person.31

You need to, in a way, be able to see the whole picture and be able to talk about it in a nice, non-judgmental way, in a way… For me, it's about keeping focus on what factors actually matter (…), to be able to refer to specific studies and not just that which is preconceived, that just because you are fat that all those factors will play a role, that one, in a way, must look at the whole picture, so if one is otherwise healthy, being fat might not necessarily be such a scary factor ….59

There needs to be more education done, specifically with doctors around how they talk to and interact with people who might be overweight or obese … and really, you're pointing out the obvious, you're telling me I'm fat, like, I don't know that. But I think there's ways of doing it in a way that, like …“Are you healthy?” “Are you a healthy person?” “Do you smoke” … they didn't ever ask me if I smoked or drank.44

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Statement of principal findings

The collective findings of this qualitative evidence synthesis describe the pervasive experience of weight stigma across primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare settings for patients living with obesity. These findings are broadly consistent with the quantitative literature documenting the verbal and non-verbal behaviors indicative of weight stigma conveyed to patients with obesity across healthcare settings.7, 61 The review goes beyond the current literature to illuminate nuances in the patient experience and offers deeper insight into how weight stigma is perceived to impact upon care delivery and treatment options.

BMI is perceived to bias HCPs attitudes toward treatment options leading to healthcare decisions being made in the absence of an investigation into the patients' history, their current lifestyle practices, weight loss efforts, and potential external factors that may influence weight or health outcomes. Patients reported that weight stigma they experienced within interpersonal interactions with HCPs migrated to the provision of care, mediated gaining equitable access to services, and perpetuated an overall poor systemic infrastructure to support the needs of patients with obesity. A non-collaborative approach to practice and treatment results in patients feeling they have no control over their own healthcare requirements.

4.2 Weight stigma in clinical practice

Weight stigma translates into clinical practice when HCPs fail to deliver compassionate, respectful, and tailored care to patients living with obesity. Across the literature, patients were often subjected to negative interpersonal interactions with healthcare providers characterized by the communication of biased attitudes around the causality and controllability of higher weight.29, 31, 34, 39, 40, 44, 46, 47, 49-55, 36 Patients described a lack of individualized care and the prescription of overly simplistic lifestyle interventions being generalized as the treatment for obesity.33, 34, 42, 47, 49, 50, 53 A reductionist approach to treatment implies that weight management is under the patients volitional control, which can deprioritize the healthcare concerns of patients with obesity; this in turn negatively impacts on continuity of care.61-63 The shifting of the responsibility of weight loss on to the patient is likely due to gaps in knowledge between contemporary obesity research and current treatments prescribed in practice.61, 63

The implications of healthcare providers holding stigmatizing beliefs are the apparent gatekeeping of access to evidence-based interventions including multicomponent behavioral interventions64 and adjunctive pharmacotherapy and surgery.13, 65 Additionally, weight stigma poses a significant barrier to patients accessing services to support non-weight-related concerns. As reported by the patients in the included studies, HCPs had the propensity to oscillate between dismissing patients non-weight-related concerns33, 35, 37, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 36, 57 and magnifying the potential risks30, 35, 40-44, 46, 48, 51, 59 associated with higher BMI. BMI was perceived to influence the quality of care patients received and mediated patients gaining equitable and timely access to healthcare services for both weight-related and non-weight-related health concerns. The denial of care from patients with obesity predicated upon an over-reliance on quantitative indicators of health is both unethical and discriminatory.66 Conversely, referring patients with obesity to services without consulting the patient fails to consider the individual needs of the person, further alienating patients from engaging with healthcare services.67

The obesity clinical practice guidelines seek to address stigmatizing medical treatment through the implementation of evidence-based practice guidelines that reflect advances in our understanding of the complexity of the disease.68-70 The guidelines recommend taking a person-centered approach to the treatment of obesity, which initiates with evidence-based discussions between patients and providers using the 5A's framework to guide the collaborative exploration of informed and individualized treatment options for patients with obesity.71, 72

4.3 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive qualitative evidence synthesis exploring weight stigma in healthcare settings explicitly from the perspective of the patient living with obesity. To maintain rigor, the quality of the included studies were critically evaluated using a standardized appraisal checklist (CASP). The majority of the included studies was of high quality, albeit there was a notable absence of researcher reflexivity in many studies that may have impacted on study research design, data collection, analysis, and the interpretations of the findings within those studies. To enhance the transparency of the review findings, GRADE CER Qual was applied. The CER Qual evaluation indicated high confidence in the findings with moderate confidence in verbal and non-verbal communication of weight stigma and lack of consistency in the delivery of care. Moderate confidence was indicated in both themes because the findings were of partial relevance to primary care settings. This corroborates previous research calling for further exploration of the patient experience of weight stigma in this setting.12

The review is limited by the inclusion of fewer male participants in the sampled studies. This is a common finding in weight stigma research, thus highlighting a recurrent gap in our understanding of the male experience of weight stigma across healthcare settings. Due to time limitations, only articles that were written in English were included in the synthesis. Therefore, the magnitude of weight stigma experienced by patients living with obesity across healthcare settings is likely underrepresented.

5 CONCLUSION

Weight stigma continues to persist within interpersonal interactions between patients and healthcare providers. This phenomenon insidiously impacts upon patients gaining timely and equitable access to required healthcare services. As suggested by the patients in the included studies, to reduce weight stigma, emphasis must be placed on improving the quality of patient–provider interactions across healthcare settings. The core conditions of person-centered care include genuinely conveying empathy and unconditional positive regard toward the patient to build rapport and cultivate a collaborative approach to addressing healthcare requirements grounded in the individual preferences of the patient.73-76 To legitimately provide non-stigmatizing person-centered care for obesity, it is essential that the quality of the patient–provider relationship is founded upon those conditions.

5.1 Recommendations for reducing weight stigma in clinical practice

- Adopt a person-centered approach to weight-based communication inclusive of person first language. Convey empathy, unconditional positive regard, and maintain a genuine interest in addressing the patients' presenting healthcare concerns.

- Promote a collaborative approach to treatment options that are grounded in the individual needs and preferences of the patient. Do not make lifestyle assumptions. Evaluate the history of the patient.

- Offer treatment options to patients that reflect contemporary advances in obesity medicine. Do not oversimplify the complexity of weight management for obesity.

- Foster an inclusive healthcare environment. Healthcare settings should be adapted to accommodate for higher weight.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LR and RC are in receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland Centre for Research Training in Digitally-Enhanced Reality (D-REAL) under Grant No. 18/CRT/6224. Open access funding provided by IReL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

LR, RC, CH, JW, OC, and RD declare no conflict of interest. Michael Crotty reports honoraria for educational events or conference attendance from Novo Nordisk and Consilient Health and is a member of a Novo Nordisk advisory board. He is a member of the Irish ONCP Clinical Advisory Group and ASOI. Michael is the co-founder and clinical lead of “My Best Weight Clinic.” Susie Birney reports funding to ICPO from the HSE, Novo Nordisk, and the European Coalition for People Living with Obesity (ECPO) and consulting fees or honoraria from Diabetes Ireland, ECPO, and Novo Nordisk. Susie is the Executive Director of ICPO and the Secretary of ECPO.