Policies to restrict unhealthy food and beverage advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets: A scoping review of the literature

Summary

Unhealthy food marketing influences attitudes, preferences, and consumption of unhealthy foods, leading to excess weight gain. Outdoor advertising is highly visible (often displayed on publicly owned assets), but the evidence supporting regulation is unclear. This systematic scoping review of academic and grey literature aimed to (1) describe potential health and economic impacts of implementing government-led policies that restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on public assets (including studies examining prevalence of advertising, associations with health outcomes and interventional studies); (2) identify and describe existing policies; and (3) identify factors perceived to have influenced policy implementation. Thirty-six academic studies were eligible for inclusion. Most reported on prevalence of unhealthy food advertising, demonstrating high prevalence around schools and in areas of lower socioeconomic position. None examined health and economic impacts of implemented policies. Four jurisdictions were identified with existing regulations; five had broader marketing or consumer protection policies that captured outdoor food marketing. Facilitators of policy implementation included collaboration, effective partnerships, and strong political leadership. Barriers included lobbying by food, media, and advertising industries. Implementation of food marketing policies in outdoor spaces and on public assets is feasible and warranted. Strong coalitions and leadership will be important to drive the policy agenda forward.

1 INTRODUCTION

Unhealthy diets are a key, modifiable risk factor for overweight and obesity1 and are a leading risk factor for the burden of disease, globally.2 Unhealthy food and beverage marketing (foods and non-alcoholic beverages high in fat, salt, and/or sugar [HFSS]) is ubiquitous around the world.3 Clear and consistent evidence demonstrates that marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages negatively influences dietary preferences and consumption among children and adults,4-7 which leads to excess weight gain and obesity.8 This occurs through increased awareness of products and brands,9, 10 increased brand loyalty,10, 11 and the reinforcement of societal and cultural norms around unhealthy foods.12

The food and beverage industries utilize a range of settings and media for marketing their products.13 Outdoor or out-of-home marketing is unique in that it is highly visible and, in most instances, cannot be avoided as people go about their daily life. Outdoor marketing includes advertising on static billboards, digital billboards, and posters, as well as sporting stadiums, public transport, and public transport waiting areas (bus shelters and train stations), which are often government-owned. Unhealthy food marketing on government assets is in direct conflict with the public health imperatives of governments.14-16 Public health advocates and international health agencies including the World Health Organization (WHO) are calling on governments to implement policies that restrict unhealthy food marketing.16, 17 The recommendation is to protect children from all unhealthy food marketing that they are exposed to—this includes outdoor settings.

To date, implementation of national government regulations to restrict unhealthy food marketing has been limited. A recent review of government policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children identified statutory regulations in 16 countries, of which only two (Chile and Quebec) included outdoor advertising.18 However, several subnational jurisdictions have banned unhealthy food marketing in various ways. In 2019 the Mayor of London introduced a ban on unhealthy food advertising across London’s entire public transport network, including underground and overground rail, buses, and bus shelters.19 In 2015, the Australian Capital Territory Government introduced a ban on unhealthy food and beverage advertising (as well as alcohol and gambling) on all government run bus services, later extended to include light rail services.20 These examples demonstrate efforts by governments to address unhealthy food marketing; however, there are complexities in the design of such policies including the criteria used to define unhealthy food and beverages, the marketing techniques or the types of media to be included, definitions of outdoor spaces, and the age group of children to be protected.18 These challenges can create loopholes that lead to weak policy designs.18

- What are the potential health and economic impacts of restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets?

- Where and how have jurisdictions implemented government-led policies that restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets, and what is the evidence of effectiveness?

- What are the reported barriers and/or facilitators to adopting and implementing of policies restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor advertising spaces or on publicly owned assets?

2 METHODS

Preliminary searching indicated a small number of studies reporting on outdoor advertising, and very few studies reporting evaluation of policies to restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces. A scoping review was therefore considered appropriate to map the existing body of literature in this field, examine the nature and extent of available evidence, across a range of publications, and study types from academic and grey literature. This method allowed researchers to begin with broad research questions, employ an iterative approach (whereby inclusion and exclusion criteria evolve as the review progresses), present a qualitative, rather than quantitative synthesis of findings, and identify gaps in the current body of evidence.23

This review has been informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute’s scoping review framework24 and reported in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines.25 A protocol to guide this scoping review was developed with input from all researchers involved with the study. Data searching, screening, and extraction were facilitated using Endnote citation manager and Covidence systematic review software.

2.1 Overview and search strategy

2.1.1 Academic literature search

A systematic search of five electronic databases (Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Global Health [EBSCO], and Business Source Complete [EBSCO]) covering a range of disciplines including health, public health, and business was conducted. Search terms were identified for each of the following concepts: “food and beverage” (food, beverage, and drink), “advertising” (advertising and marketing), and “outdoor/public assets” (outdoor, public, train, subway, and bus). Search terms were applied to title, abstract, and keyword searches. Subject headings were used where applicable, and the search strategy was translated as necessary for each database. No date limits were set. Reference lists of all included articles were scanned for additional relevant studies. The search was conducted in August 2020.

2.1.2 Grey literature search

As recommended for grey literature searches, we used a variety of methods to iteratively search for relevant grey literature across a number of sources.26-28 We manually searched the following policy databases: World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) NOURISHING database (www.policydatabase.wcrf.org; an overview of government policy actions implemented around the world), the World Health Organization (WHO) Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA) (www.who.int/nutrition/gina; a platform for information on nutrition policies and action around the world), and Australia’s Obesity Evidence Hub (www.obesityevidencehub.org.au; a website that aims to identify, analyze, and synthesize evidence on obesity worldwide), to identify jurisdictions where government-led policies have been implemented to restrict advertising in outdoors spaces or on publicly owned assets. Google Scholar was used to locate any additional relevant details for the policies and jurisdictions identified in the policy database searches, scanning the first 10 pages (100 entries) returned for each search.

A focused search of government websites of jurisdictions that were identified to have had relevant policies implemented was undertaken to identify further details of regulatory design and any details on policy evaluation and impact (e.g., regulatory impact statements). Where we identified that a policy had been implemented in a jurisdiction but could not find further information relating to the policy on the government website, we contacted our known networks for additional information.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

2.2.1 Academic literature

Inclusion criteria for this review was intentionally broad, designed to capture the objectives of the review.29 Because preliminary searches returned very few studies evaluating real-world policies, we included studies reporting the prevalence of, or exposure to, unhealthy food marketing in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets to identify the potential exposure to and impacts of advertising. We also included articles reporting the association between unhealthy outdoor advertising and diet and obesity outcomes to understand the potential impacts of advertising on health outcomes.

Reviews and qualitative and quantitative studies were eligible for inclusion if they met at least one of the following criteria: (i) The study reported on the implementation (including barriers and facilitators) or evaluation of government-led or government-approved co-regulatory policies to restrict unhealthy food or non-alcoholic beverage advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets or (ii) the study reported on the prevalence or impact of unhealthy food or non-alcoholic beverage advertising in outdoor spaces (including, but not limited to, billboards, digital billboards, posters, public transport and public transport waiting areas [bus shelters and train stations], shopping centers, or building exteriors) on food consumption or health. Advertising was defined as material published that draws the attention of the public to promote a product, service, or organization.30

Articles were excluded for the following reasons: (i) The study examined unhealthy food and beverage marketing in media and settings outside the scope of this review (e.g., television, online, in schools, or in retail stores); or (ii) the study was not published in English; or (iii) the article was a conference abstract, book, editorial, letter to the editor, news article, or commentary.

2.2.2 Grey literature

Grey literature was deemed relevant if it reported on any aspects of a government-led policy to restrict unhealthy food and beverage marketing in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets, including policy implementation or evaluation. This included policy documents (i.e., policy proposals, implementation plans, or evaluations), media releases, and reports from inter-governmental agencies and non-government organizations (NGOs) (e.g., the WHO and WCRF). Government-led and government-endorsed co-regulatory policies were included; industry-led codes were excluded from this review.

2.3 Article selection

2.3.1 Academic literature

Following the search process and removal of duplicates, all titles and abstracts were screened independently by two members of the research team (AC and DR). Each article deemed potentially relevant based on title and abstract was obtained, read in full, and assessed against the eligibility criteria by one author (AC). The first 25% of full text articles were assessed in duplicate by a second author (DR), with discrepancies discussed and resolved between authors. Because there was high concordance between authors (95%), all remaining articles were assessed by a single author (AC).

2.3.2 Grey literature

One author (CZ) conducted the grey literature search and extracted all potentially relevant data. Potentially relevant data were cross-checked for inclusion by a second author (KB). Any queries (e.g., concerning the type and depth of information being retrieved) were iteratively discussed between CZ and KB and, where necessary, resolved with other members of the research team.

2.4 Data charting

Charting tables were developed and piloted during the development of the review protocol. These tables were used to record key details of each included article from the academic and grey literature.

2.4.1 Academic literature

The following information (where available) was recorded from academic literature: authors, title, publication date, setting (country or town), study design (observational study, modelling study, and evaluation), study aim, summary of policy design, advertising media, key evidence used to support the policy, key findings, or recommendations of the report or study.

2.4.2 Grey literature

The following information (where available) was extracted and recorded from grey literature sources: characteristics of regulatory design, including the regulatory system (mandatory/voluntary), policy objective, food classification system, advertising content (e.g., marketing intent or techniques) and media covered by the policy, regulatory exemptions, and monitoring system. We also collected information related to policy evaluation, including the potential impact on advertising, health, or economics. Factors perceived to have influenced policy adoption or implementation were also recorded.

2.5 Critical appraisal

The purpose of this scoping review was to map and describe existing evidence across the academic and grey literature; therefore, appraisal of the methodological quality of included evidence was not conducted.31, 32

2.6 Synthesis of results

A narrative synthesis was considered the appropriate method to synthesize findings to answer our review objectives due to the heterogeneity in the studies and document types retrieved across academic and grey literature sources. To do this, evidence collated from academic and grey literature sources was tabulated and subsequently mapped to each of the three research questions.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Selection of sources of evidence

3.1.1 Academic literature

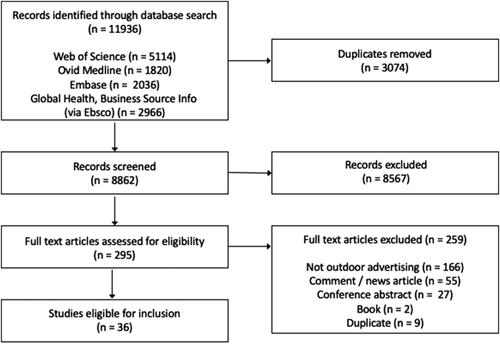

The academic literature database search returned 11,936 potentially relevant citations. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts for relevance, 295 full text articles were retrieved and reviewed in full. Of these, 36 articles were included in the review after assessment against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). The primary reason for exclusion was not reporting on advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets.

3.1.2 Grey literature

Grey literature searching identified relevant policy information from the WCRF NOURISHING database (n = 10), the WHO Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA; n = 9), and Australia’s Obesity Evidence Hub (n = 3). A Google search revealed details of the implementation of two further potentially relevant policies. After removing duplicates and assessing policies against the inclusion criteria, nine policies from various jurisdictions were included for a focused search of relevant government websites to identify additional details for each policy.

3.2 Characteristics of sources of evidence

3.2.1 Academic literature

A majority of studies reported on data obtained in the United States (n = 11), Australia (n = 10), and New Zealand (n = 6), with a further two studies from the United Kingdom and one each from Canada, Sweden, Chile, Ghana, Jamaica and Indonesia, The Philippines and Mongolia (the latter two included in a single study).

Of the 36 included studies, 28 reported on the prevalence of unhealthy advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets33-60; two reported associations between outdoor marketing and consumption of unhealthy food6, 61; one reported associations between outdoor advertising and the school food environment58; one reported outdoor advertising and neighborhood level obesity rates62; two reported on policy options for regulating unhealthy food marketing in outdoor environments63, 64; two reported on public opinions towards marketing regulation65, 66; and one study reported an evaluation of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising.67 A detailed description of all included studies from the academic literature is reported in Table S1. From the grey literature, we identified nine jurisdictions with relevant policies in place.

3.2.2 Grey literature

Nine jurisdictions were identified with government-led policies that ban or restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. These policies were diverse in policy objectives, the media type and food groups covered, and the regulatory system used. Seven of these were statutory regulations, and two were government-led voluntary regulations. The regulatory details for each of these policies is summarized in Table 1.

| Jurisdiction | Policy objective/scope | Food classification system | Advertising content and media | Monitoring system and evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policies focused on public assets—Mandatory | ||||

| London (2019) Revision of the TfL advertising policy | Updated standards for advertisement approval. The promotion (directly or indirectly) of food or non-alcoholic drink which is high in fat, salt, and/or sugar (HFSS) cannot be advertised on services run or regulated by TfL.19 The policy is integrated with the London Food Strategy.68 | Public Health England’s Nutrient Profiling Model used to classify high fat, sugar, and/or salt (HFSS) products.69 |

Content: Graphics and text promoting HFSS foods and drinks (visual content, in-text references, brands, and incidental placement) Media: London underground, rail, buses, overground, light railway, roads (e.g., roundabouts and bus stops owned by TfL), river services, tram, Emirates Air Line, Victoria coach station, Dial-a-Ride, taxi, and private hire. Exemptions: Brands can be included if the advertisement promotes healthy products as the basis of the advertisement (e.g., sugar free drink).69 |

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is evaluating the impact of the regulation on sales of HFSS foods and drinks (April 2019–March 2021). |

| Australian Capital Territory (2016) ACTION bus services advertising policy | Restrictions on the promotion of unhealthy food on government-run bus services and light rail to ensure that the promotion of products is appropriate for the broader population and aligns with the values of the community and Government objectives.20 Stated alignment with the Towards Zero Growth: Healthy Weight Action Plan.70 | Unhealthy food and drinks as defined by the Australian Dietary Guidelines and associated Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.20 | Media: Government-run buses and light rail services. | None identified |

| Amsterdam (2018) Amsterdam Healthy Weight Program | Ban on billboard advertisements for unhealthy products targeted at children and teenagers (up to 18 years of age) in any of Amsterdam’s 58 metro stations.71, 72 | National nutrition guidelines from the Netherlands Nutrition Centre.73 | Media: Billboards at metro stations (n = 58). | None identified. |

| Brazil (2016) Ordinance (No 1.274) on healthy food procurement | Aim to address overweight, obesity and non-communicable diseases and based on the right to adequate food. Prohibits advertisements and sales promotions of ultra-processed food products on the premises of the Ministry of Health and its entities.74 | Ultra-processed productsa defined by the Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profiling Model.74 | Media: Ministry of Health premises and entities. | The Brazilian Ministry of Health is responsible for monitoring and evaluation. |

| Broad policies (including outdoor advertising restrictions)—Mandatory | ||||

| Chile (2016) Food Labelling and Advertising Law | Protect children, promote informed selection of food, and decrease the consumption of food with excessive amounts of critical nutrients. The policy is focused on child-directed advertising (where children are defined as <14 years).67 Outdoor spaces and publicly owned assets inherently captured as part of the broad Food labelling and Advertising Law. | Foods and beverages “High” in energy, fat, salt, and/or sugarb cannot be advertised. | Content and media: All forms of child-directed marketing techniques across any communication channel. | Compliance monitored by an inter-sectoral network including government agencies, academia, NGOs, consumer associations food marketing, and consumers’ rights organizations.75 |

| Latvia (2016) Law on the Handling of Energy Drinks | Protect human health from the adverse effects of energy drinks on the body. The government regulated law aims to restrict the marketing of energy drinks as well as prohibiting the sale of energy drinks to children <18 years.76 | Energy drinks containing >150 mg/L caffeine and one or more other stimulants such as taurine and guarana. |

Content: Any association with sports activities, energy drinks cannot be offered for free to children <18 as a promotion. Media: Educational establishments and on the buildings and structures of these institutions. |

None identified |

| Quebec (1980) Quebec’s Consumer Protection Act (Section 248) | Bans any commercial advertising (including outdoor) directed at children <13 years, including food and beverage marketing. | No food classification system. |

Content: promotion that is intended for children; the appeal of an advertisement to children; and whether children are likely to be exposed to the advertisement. Media: Signage, use of promotional items. Exemptions: Children’s entertainment events, in-store windows, and on-pack advertisement (if they meet certain criteria). |

No formal monitoring body; complaint and media reports are submitted to report non-compliance. |

| Broad policies (including outdoor advertising restrictions)—Voluntary | ||||

| Ireland (2018) Voluntary Codes of Practice | Aim to reduce exposure of the Irish population to marketing initiatives relating to HFSS foods.77 | Nutrient profile model used by the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland. |

Content: No licensed characters or celebrities that are popular with children, promotions, competitions. Media: non-broadcast media, including all forms of digital media, out-of-home media, print media, and cinema. Out-of-home media includes billboards or hoardings, public transport stops or shelters, interiors and exteriors of buses or trains, or building banners. Exemptions: Corporate social responsibility initiatives, donations, or patronage. |

Government body and monitoring framework designated to monitor these Voluntary Codes of Practice for compliance. |

| Finland (1978; updated in 2016) Finnish Consumer Protection Act | Regulates all marketing, including food marketing to children (<18 years). Food advertisements should not be misleading and should not encourage unhealthy dietary habits in children.78 | No guidance on food classification or what is considered as marketing to children. |

Content: Food advertisements must have an explicit purpose; advertising cannot be misleading or promote unhealthy diets among children. The appropriateness of marketing to children is examined on a case-by-case basis. Media: All media including outdoors. |

Consumer Ombudsman in collaboration with the food industry to ensure marketing aligns with the guidelines. Over the last 10 years, no cases have been taken to court. |

- a Food mainly produced from the processing of unprocessed food and/or other organic matter, containing ≥1 mg of sodium per 1 kcal, ≥10% of total energy from free sugars, ≥30% of total energy from total fat, ≥10% of total energy from saturated fat, and ≥1% of total energy from trans fat.

- b For food, “High” products contain energy >275 kcal/100 g, sodium >400 mg/100 g, total sugar > 10 g/100 g, and saturated fat >4 g/100 g. For beverages, “High” products contain energy >70 kcal/100 g, sodium >100 mg/100 g, total sugar > 5 g/100 g, and saturated fat >3 g/100.

3.3 Synthesis of results

3.3.1 Research Question 1: What are the potential health and economic impacts of restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets

No studies reported directly on the health or economic impacts of government restrictions on unhealthy food and beverage advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. However, 27 studies were identified that reported on the prevalence of unhealthy food and beverage advertising in outdoor spaces, demonstrating the nature and extent of this type of advertising. A further four studies examined associations between outdoor unhealthy food advertising and health-related outcomes, from which we can infer potential health impacts of policies to ban unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets on diet or health-related outcomes. Evidence from the grey literature was found to demonstrate the economic impacts of banning unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets. Each of these findings are discussed below.

Prevalence of unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets

Twenty-seven studies reported on the prevalence of advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. For example, a New Zealand study found that 30% of children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing occurred in public spaces.56 Sixteen studies reported on unhealthy outdoor advertising according to socioeconomic position (SEP). Fourteen studies (from the United States,34, 37, 38, 41, 43, 48, 59 the United Kingdom,51, 79 Stockholm,40 Canada,57 Australia,54, 55 and New Zealand58) demonstrated socioeconomic differences in unhealthy food advertising in outdoor areas, with unhealthy food marketing more prevalent in areas of lower SEP. Conversely, two studies (one from Australia53 and one from the United States60) found no SEP differences in the prevalence of outdoor marketing of unhealthy food and beverages.

Twelve studies reported on outdoor advertising specifically in areas surrounding schools. These studies, undertaken in various countries (Australia,44, 52, 53 New Zealand,39, 42, 46, 49, 58 Canada,57 the USA,41, 43 and Manila, The Philippines, and Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia45), consistently showed that unhealthy food and beverage advertising is prevalent in areas around schools. For example, one Australian study of advertisements within a 500-m radius of primary schools in Sydney and Wollongong found that 80% of food and beverage advertisements were promoting unhealthy food, beverages and alcohol.44

Seven studies specifically examined food and beverage advertising on public transport.40, 42, 48, 52-55 For example, a 2019 study of advertisements in and immediately surrounding subway stations in Stockholm, Sweden, found 32.8% of advertisements promoted food products and of those, 65.4% promoted ultra-processed products (defined as processed food and beverages typically high in fat, salt and/or sugar, that are convenient, highly palatable, and heavily marketed80).40 A study in Perth, Australia, analyzed advertisements on every bus shelter within 500 m of schools within five local government areas and found 31.4% were promoting unhealthy products. Food represented the largest proportion of unhealthy advertisements, accounting for 56.5% of all advertisements in the unhealthy category (including fast food, ice cream, confectionary, and chocolate). Less than 1% of advertisements (0.7%) promoted a healthy product.52 Another study in Sydney examined advertisements at 178 stations across the Sydney metro train network, finding 27.6% of all identified advertisements were for food or beverages. Of the food and beverage advertisements, 84.3% were promoting unhealthy food.54

Potential health impacts of policies to ban unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets on diet or health-related outcomes

No studies were identified that specifically examined the health impact of policies restricting unhealthy food advertisements in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. Four studies examined associations between outdoor unhealthy food advertising and health-related outcomes. Two studies, one each in Australia and Indonesia, reported a positive association between exposure to unhealthy food marketing (including on public transport) and consumption of unhealthy food.6, 61 A US study found positive associations between outdoor food and beverage advertisements and obesity such that for every 10% increase in food advertising in a neighborhood, residents had 1.05 (95% CI 1.003–1.093, p < 0.03) greater odds of overweight or obesity.62 A New Zealand qualitative study reported on the food environment, including food and beverage advertising surrounding schools and associations with the food environment within schools. Principals, teachers, and parents from schools with a higher percentage of students passing food outlets and advertisements considered that their presence impacted efforts within their school to improve the food environment.58

Potential economic impacts of banning unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets

No literature was identified that specifically reported on the economic impacts of policies that ban unhealthy food advertising in outdoor environments or on publicly owned assets. However, some relevant evidence relating to the revenue generated by advertising and therefore the potential economic implications of banning unhealthy food advertising on public transport was identified in two documents. The first was the Annual Report and Statement of Accounts (2019/2020) for the Transport for London (TfL), which reported an increase in commercial advertising income (2.8%) between 2019 and 2020 (policy implemented in February 2019).81 The second was documentation from a Western Australian Parliamentary debate (Hansard) in February 2020 where, in response to a question to the Department of Transport, it was reported that the income paid to the Public Transport Authority from all food and beverage advertising was $1,006,050 in 2017–2018 and $1,002,984 in 2018–2019.82

3.3.2 Research Question 2: Where and how have jurisdictions implemented government-led policies that restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets, and what is the evidence of effectiveness?

London, Amsterdam, and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) have implemented policies to ban unhealthy food and beverage advertising on their public transport networks. In London, the TfL advertising policy was revised in 2019 to update standards such that the promotion (directly or indirectly) of food or non-alcoholic beverages high in fat, salt, and/or sugar can no longer be advertised on services run or regulated by TfL.19 In 2018, Amsterdam, as part of the Healthy Weight Program, banned advertisements of unhealthy food products targeted at children and teenagers (up to 18 years of age) across Amsterdam’s 58 metro stations.71 In the ACT, as part of the ACTION bus services advertising policy, the promotion of unhealthy food and drinks on government-run bus services and light rail has been banned since 2016.20

In 2016, Brazil implemented a specific policy that bans unhealthy food and beverage advertising across all Ministry of Health premises and its entities.74 This is part of a broader Ordinance (No 1.274) on healthy food procurement to address overweight, obesity, and non-communicable diseases, underpinned by the human right to adequate food.74

Advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets is also inherently captured in other broad-based laws. The Chilean Food Labelling and Advertising Law bans “child-directed” marketing (to children under the age of 14 years) across all media. Similarly, the consumer protection legislation in Quebec prohibits commercial advertising that is “child-directed” (aimed at children <13 years) across all media, including food and beverages.67 In Latvia, under the Law on the Handling of Energy Drinks, the advertising (and sale) of energy drinks to children <18 years is prohibited within and on the exterior buildings of educational establishments.76

A further two government-led voluntary regulations were identified in Ireland and Finland. In Ireland, under the Government-led Voluntary Codes of Practice (2017) (the Codes), the marketing of foods high in fat, sugar, and salt should not be marketed in non-broadcast media, including all forms of digital media, out-of-home media, print media, and cinema.77 Out-of-home media includes billboards or hoardings, public transport stops or shelters, interiors and exteriors of buses or trains, or building banners. The Codes also stipulate that advertisements for HFSS foods be restricted to placement at least 100 m from the school gate for large roadside billboard formats. The Codes were co-developed with industry, with no statutory basis.77 The Finnish Consumer Protection Act regulates marketing across all media, including food marketing to children (<18 years), stating that food advertisements should not be misleading and should not encourage unhealthy dietary habits in children. However, the guidelines supporting the implementation of the Act, which are not legally binding, do not provide guidance on food classification or what is considered as marketing to children.78

3.3.3 Research Question 3: What are the reported barriers and/or facilitators to adopting and implementing of policies restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor advertising spaces or on publicly owned assets?

The factors perceived to have influenced the adoption or implementation of policies restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets have been categorized as likely facilitators of policy adoption or implementation and likely barriers. These are summarized in Table 2, with additional details provided in Table S2.

| Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Wide-spread support among stakeholders, including the general public | Industry opposition, including legal challenges |

| Strong political will and a political champion with power | Disagreement over definitions including what age defines a child, choice of reference nutrition models/criteria to classify foods as unhealthy |

| Effective partnerships between key stakeholders | Perception of negative impact on government revenue |

| Rights-based framing, i.e., protecting children | Lack of political will |

| Policy coherence | Weak or unclear mechanisms for monitoring and enforcement |

| Existing legislative frameworks | Insufficient public demand/support |

Policy facilitators

Common factors identified that ultimately facilitated policy adoption included collaboration and coalitions among multi-sectoral actors and effective partnerships across levels of government, academia, and NGOs, backed by strong and influential political leadership and championing.83, 84 For example, in London, key stakeholders included the Mayor of London (political champion and chair of the Transport for London Board), Public Health England and other NGOs (public sector lobbying and advocacy), the Greater London Authority and Transport for London (drafting of policy and consultation), Transport for London (policy implementation), London boroughs and the London Food Board (general policy support) and local universities (policy evaluation).

Policy alignment and a common policy agenda were also identified as key facilitators to policy adoption.21 For example, the ACT policy to restrict the promotion of unhealthy food on government-run bus services and light rail aligned with the “Towards Zero Growth: Healthy Weight Action Plan.”70 The TfL ban aligned with local government policies on “Sugar Reduction” and “Healthier Foods” (hence gaining the support of London boroughs).83 Similarly, the Amsterdam ban across 58 metro stations was implemented as part of the city’s Healthy Weight Program.72 Embedding the policy in a long-term vision and including clear policy objectives were also identified as critical, particularly during changes of leadership.72, 84 Lastly, policy framing around child or rights has been reported to facilitate policy adoption and is used in advocacy to support regulatory action.85, 86

Four additional studies examined public support and existing legislative tools as potential facilitators of policy adoption (but were not connected to any specific policy).63-66 Three of these, conducted in Australia, cited support from government stakeholders and the general public as key facilitators for policy adoption. In the first of these studies, more than 80% of surveyed Victorian government stakeholders indicated support to restrict non-broadcast marketing (internet, billboards, and sport sponsorship) in 2009–2010.64 Public support for government policy to restrict unhealthy food and beverage advertising in public spaces (e.g., bus stops and train stations) was also strong in a nationally representative sample of Australian adults, with 70% of participants agreeing that there should be at least some government regulation to protect the public.66 When framed as regulation for protecting children, the level of support increased to 78.9%.66 In the third study, 92% of sampled mothers supported restrictions on unhealthy food advertising in and around public transport.65 The fourth Australian study identified three legislative and three non-legislative government planning tools in the state of Queensland that could be used to limit unhealthy food advertising. Legislative tools include Corporate and Operational plans, local laws and State planning policies. Non-legislative tools were identified as complements to legislative processes and included community public health planning, community renewal, and health impact assessments.63

Policy barriers

Political lobbying by the food, media, and advertising industries was the most frequently identified challenge to adopting and implementing regulations to restrict unhealthy food advertising. Multiple forms of lobbying were identified, including the risk of legal threats and lawsuits and criticizing and challenging the regulatory design of proposed policies.83, 87 Lobbying such as this has previously been demonstrated to lead to watering down of the scope and regulatory design of nutrition policies.88 Watering down of outdoor policies was observed in the ACT, Australia, where policy changes were observed following an initial consultation on the promotion and marketing of unhealthy foods. The original consultation sought views and ideas on many different types of marketing, including at sporting venues and at government venues and events, however the adopted policy only included advertising restrictions on government-run buses, and later, light rail.20

Other challenges identified included a perceived risk of reduced advertising revenue for governments,83 potential policy loopholes such as cross-border advertising, rendering the policies ineffective,89 weak or unclear mechanisms for enforcement and monitoring of policies,90 and perceived inadequate public support for policy action.91

4 DISCUSSION

The findings from this scoping review demonstrate that government-led policies to restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets are warranted and that policy adoption and implementation is feasible. The studies included in our review highlight the global and ubiquitous nature of unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets. Combined with the broader evidence on the impact of food marketing on children’s food preferences and intake, our findings suggest that government-led policies are necessary to reduce children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing.

The high prevalence of unhealthy food advertising was particularly evident in locations surrounding schools and on children’s routes to school, with a higher volume of unhealthy food advertising in neighborhoods experiencing greater socioeconomic disadvantage. No studies were identified that evaluated existing policies that have banned unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. Only two studies were identified that examined the association between these types of advertising and food consumption, both of which reported positive associations between exposure to unhealthy food marketing and consumption of unhealthy food.6, 61 When considered alongside the broader literature on unhealthy food marketing (through other media), the evidence is strong that marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages influences attitudes, preferences, expectations, and consumption of these products across the life-course.4, 10 Evidence also shows that unhealthy food marketing increases unhealthy food consumption4 and total energy intake,10 which, over time, leads to excess weight gain and obesity.8

Nine jurisdictions that have adopted policies to restrict unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets were identified. Four of these policies were implemented at the national level, and five were within a city or state/province. Four identified policies specifically focused on publicly owned assets, of which three focused on public transport (London, Australian Capital Territory and Amsterdam) and one focused on Ministry of Health premises and entities (Brazil). The remaining five jurisdictions (Chile, Latvia, Ireland, Finland, and Quebec) have implemented broader-based policies (consumer protection law or broad-based advertising laws), which inherently capture marketing in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets. While this precedent demonstrates the feasibility of enacting such policies at the national and local levels, it also highlights several limitations with existing policies. First, while restricting unhealthy food advertising on publicly owned transport is likely to have large reach, as evidenced by the large volumes of unhealthy food advertising identified in this scoping review, it does not capture the full range of government owned assets, which also includes sports stadiums, billboards, and signage in public spaces and at public events. Second, a key limitation of the broader-based policies is the tendency to focus on marketing that is “directed to children” (Chile, Quebec, and Finland). Policies that are narrowly focused on marketing that is “directed to children” can be difficult to enforce (and are therefore less effective) due to the complexities with different interpretations of the intended audience.67 They also fail to protect children from being exposed to unhealthy advertising that is targeted towards older audiences. Third, two of the policies identified were voluntary in nature. Independent evaluations assessing the effectiveness of both government-led voluntary regulation and industry-led self-regulation in relation to other marketing media consistently indicate that the impact of both approaches on reducing the exposure and power of marketing to children is limited.92 Research in Australia found that the frequency of food advertising and children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing on television remained unchanged despite the implementation of industry self-regulatory pledges.93 Mandatory regulation creates a level playing field for businesses, where compliance is not left to the voluntary commitment of industry. This removes any possibility of a company attempting to gain market advantage through non-compliance (an option that is still open to them under voluntary or self-regulation).94 Finally, several policies included exemptions. For example in London brand marketing is permitted if the advertisement promotes healthy products.69 This is problematic as brand marketing (the use of brands alone or company branding alongside healthy options) that is primarily associated with unhealthy products has shown to increase reward pathways in the brain and to increase selection and consumption of unhealthy products.95, 96 It is recommended that policies that ban unhealthy food advertisements on publicly owned assets cover all entities and assets owned by government and all marketing of unhealthy food products and brands to which children are exposed (regardless of intended audience of the advertisement).16

To date, none of the policies identified in this study have been evaluated to assess their impact on exposure to, or consumption of, unhealthy foods. While evaluation studies have demonstrated a decline in purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages following implementation of Chile’s Food Labelling and Advertising Law, attribution of these effects to the food advertising ban (let alone changes in outdoor advertising) is not possible when other policies, including food labelling and school food policies were implemented around the same time.67 As a result, conclusions on the effectiveness of such policies or any financial implications cannot be made at this point in time. This review found no evidence to date to suggest that government regulation of outdoor advertising will have negative financial impacts for governments. In fact, the literature that was identified suggested the opposite. Advertising revenue from TfL assets slightly increased in the year following policy implementation compared to previous years.81 However, minimal conclusions can be made with this limited data as the trend in revenue may have been increasing year on year. In Western Australia, the Department of Transport reported that the Public Transport Authority received an income of approximately $1 million per year in 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 from all food and beverage advertising.82 This is a relatively small amount compared with the current estimates on the cost of obesity, which is estimated to reach $610 million annually in Western Australia by 2026 if current trends continue.97

Political lobbying and arguments opposing regulation by the food, media, and advertising industries were consistently identified as key challenges to adopting and implementing regulations to restrict unhealthy food advertising in jurisdictions with existing policies in place. Industry lobbying and opposition is recognized as a major barrier to nutrition policy.98 These actions, including the risk of legal threats and lawsuits, criticisms of regulatory design, and negatively framing policy and public discourse, may lead to watering down of policy scope and regulatory design88; however, we cannot say this for certain as assessments of the evolution of policy design was out of the scope of this review.

The drivers of political commitment to nutrition are complex and context dependent.21 Building commitment is underpinned by effective nutrition actor networks characterized by strong leadership and cohesion among members including parliamentarians, bureaucrats, academics, and civil society representatives.21 Factors enabling the successful implementation of nutrition policies include policy framing that resonates with political leaders and the public,99, 100 cohesive and collective advocacy by multi-sectoral actors, and strong and influential leadership with a long-term vision.21, 101

While we identified studies reporting on the prevalence of unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets, our study identified few studies reporting on the impact of outdoor advertising on dietary behaviors. However, the mechanisms through which unhealthy food marketing influences dietary behaviors is unlikely to be vastly different across media and settings. Therefore, when combining the evidence from our review with the broader evidence base (e.g., the impact of television marketing on dietary behaviours4, 10), it is highly likely that unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets also has negative implications for population diets and health. While this study identified a number of jurisdictions with regulations in place to reduce exposure to unhealthy food advertisements in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets, we did not find any evidence on the effect of removing unhealthy advertising in outdoor spaces or on publicly owned assets. It will be important that existing policies in this area are evaluated and communicated to support international advocacy efforts and policy adoption and implementation.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this scoping review is the comprehensive, systematic searching of academic and grey literature. The review was guided by a protocol developed by a research team with expertise in reviews and knowledge synthesis and conducted in accordance with the PRISMA ScR guidelines.25 The search strategy included five academic literature databases, three policy databases, and government websites. Data searching, screening, and extraction were rigorous and transparent, with citation manager (Endnote), systematic review software (Covidence), and pretested Microsoft Excel spreadsheets used to account for all articles and grey literature sources.

Given this review was conducted as part of a rapid obesity policy translation project, the study protocol was not pre-registered. Because of the scoping nature of the review and the limited available literature related to existing policies restricting unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces, our results on the barriers and facilitators to policy implementation are somewhat cursory. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of effective policy implementation can help inform policy processes, increasing the likelihood of effective implementation.22 Therefore, future research should seek to provide a deeper understanding of barriers and to effective implementation of public health policies. A further limitation of this review is that it only focused on unhealthy food marketing in outdoor spaces and publicly owned assets, and therefore, the relative prevalence of unhealthy food advertising and policy adoption to limit exposure through other settings and media is unknown. The findings of this review should be interpreted in the context of recommendations for a comprehensive regulatory design, across multiple advertising media, to protect the population from the harmful impacts of unhealthy food marketing.16

5 CONCLUSION

Unhealthy food advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets is ubiquitous and cannot be avoided. Comprehensive government regulation is necessary to protect the population from the impacts of unhealthy food marketing in outdoor spaces. Greater volumes of this type of advertising in disadvantaged neighborhoods suggest that action to remove unhealthy advertising is likely to improve population diets and reduce inequalities in diet-related morbidity and mortality across the life-course. This study demonstrates the feasibility of government regulation to reduce exposure to unhealthy food advertisements in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets. Several jurisdictions have successfully implemented regulation that bans the advertising of unhealthy food and beverages on government-owned assets. However, none of the regulation to date covers the full breadth of government owned assets or adequately covers all unhealthy food and brand advertisements to which children are exposed. Governments around the world have the responsibility to demonstrate global leadership in this regulatory space and invest in the future health of their populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This scoping review was supported by Cancer Council Western Australia as part of a rapid obesity policy translation project, funded by the Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation, Healthway.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AC, DR, JA, and KB report grants from Cancer Council Western Australia and Telethon Kids Institute during the conduct of the study; AS and KK report grants from Healthway during the conduct of the study; JA reports grants from Cancer Council Western Australia, National Health and Medical Research Council, World Health Organization, Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education outside the submitted work; KB reports grants from National Heart Foundation of Australia, Australian Research Council, National Health and Medical Research Council and personal fees from UNICEF outside the submitted work.