Symptoms from the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index and clinical factors associated with delayed gastric emptying in patients with suspected gastroparesis

Abstract

Background

The association between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and delayed gastric emptying (GE) shows conflicting results. This study aimed to assess whether the symptoms of the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) and/or the scores were associated with the result of GE tests and whether they could predict delayed GE.

Methods

Patients referred for suspected gastroparesis (GP) were included in a prospective database. Demographical data, medical history, and symptoms of the GCSI score were collected for each patient. A GE scintigraphy was then performed with a 4-hour recording. Delayed GE was defined as a retention rate ≥ 10% at 4 h.

Results

Among 243 patients included in this study, 110 patients (45%) had delayed GE. The mean age (49.9 vs. 41.3 years; p < 0.001) and weight loss (9.4 kg vs. 5.6 kg; p = 0.025) were significantly higher in patients with delayed GE. Patients with diabetes or a history of surgery had a higher prevalence of delayed GE (60% and 78%, respectively) than patients without comorbidity (17%; p < 0.001). The GCSI score was higher in patients with delayed GE (3.06 vs. 2.80; p = 0.045), but no threshold was clinically relevant to discriminate between patients with normal and delayed GE. Only vomiting severity was significantly higher in patients with delayed GE (2.19 vs. 1.57; p = 0.01).

Conclusion

GE testing should be considered when there are symptoms such as a higher weight loss, comorbidities (diabetes, and history of surgery associated with GP), and the presence of vomiting. Other symptoms and the GCSI score are not useful in predicting delayed GE.

Key points

- The distinction between functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis can be challenging, and the indications to refer patients for a gastric emptying test should be clarified.

- Patients with previous surgery, diabetes, a higher weight loss, and more severe vomiting symptoms were more likely to have delayed gastric emptying.

- The Gastric Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) was higher in patients with delayed gastric emptying, but no threshold could predict the result of emptying test.

1 INTRODUCTION

Gastroparesis (GP) and functional dyspepsia (FD) are the two most common disorders of the gastroduodenal region.1 They both share similar upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, such as postprandial fullness, bloating, or early satiation, and similar pathophysiological features.2, 3 Therefore, the distinction between FD and GP remains tricky and debated in the literature.4, 5

The objective measurement of delayed gastric emptying (GE) of solid food is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of GP.6 The prevalence of diagnosed GP is low, estimated at 0.02%, but it might be due to the under-diagnosis of the disease.7 Epidemiological evaluations consider that delayed GE could reach up to 1.8% of the population including patients with undiagnosed, or “hidden gastroparesis.”8 This low diagnostic rate could also be due to the difficult access to the measurement of GE, with either GE scintigraphy or 13-Carbon octanoic acid breath test.9, 10 Indeed, these techniques can be expensive, and time-consuming requiring evaluation for at least 4 hours.11

FD is defined by Rome IV criteria by the presence of persisting postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, or burning, with no evidence of structural disease.3 The prevalence is very high estimated at 7.2% in the global population.1 However, up to 30% of patients with FD have delayed GE, and should not be considered as GP, making the distinction between these two entities more difficult.12 Consensus on FD agrees that GE measurement should not be performed when considering this diagnosis.13 Moreover, a recent study showed that GE results might change 48 weeks apart, and assessed that FD and GP are interchangeable diagnostics in tertiary centers.14 Therefore, clinical criteria to select patients who should be referred for an objective measurement of GE are required.

The Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) is a subjective score used to assess symptom severity in GP.15 This score includes nine symptoms assessed on a Likert scale from 0 (absent) to 5 (very severe) during the past 2 weeks. It has been used for the follow-up of the patients and to define the response to treatments. However, data assessing whether this score could be used as a diagnostic tool are scarce.16 Indeed, the concordance of GE tests with each clinical symptom of GP is variable among studies.17, 18

The aim of our study was to determine the factors and symptoms associated with delayed GE in patients with upper GI symptoms suggestive of GP and to determine whether the GCSI score could be used as a diagnostic tool or not.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Patients

This is a retrospective monocentric study from a prospectively collected database. Consecutive patients referred to the gastroenterology department of the Louis Mourier Hospital between 2015 and 2021 for upper GI symptoms suggestive of GP were included in a prospective database. A specifically dedicated consultation was offered to these patients, and the demographic characteristics, the GCSI scores, and the clinical evaluation of the patients were recorded in a database. The decision of whether patients could then be referred to a GE test or not was left to the clinician choice. Thus, the inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: the presence of upper GI symptoms suggestive of GP (i.e., postprandial fullness, early satiation, bloating, nausea, and/or vomiting), collection of the GCSI score at the initial consultation, and performance of a GE scintigraphy. Exclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of an obstacle on endoscopy or imaging (n = 2), patients who performed a previous endoscopic (botulinum toxin injection in the pylorus, pyloric dilatation, gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy (G-POEM)) or surgical treatment for GP (gastric electrical stimulation), and patients who have had a non-compliant GE test as detailed in the GE scintigraphy section. All the patients gave their informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The study responds to MR004 national laws in France (Decision no. 2018-155, 05 March 2018) about research of public interest.

2.2 Clinical evaluation

During the medical consultation, demographical data (age, sex), biometric data (weight, height, and body mass index), and medical and surgical history were systematically collected in our database. Only surgeries with a higher risk of delayed GE were reported (fundoplication, Ivor Lewis surgery, lung transplantation, and pancreatic surgeries). Weight loss before the consultation, as well as the duration of the symptom evolution, was numerically reported. Each symptom of the GCSI score was collected prospectively according to the Lickert scale reported by Revicki et al.15 This included nausea, retching, vomiting, postprandial fullness, inability to finish a meal of normal size, early satiation, loss of appetite, bloating, and abdominal distension. The overall GCSI score and the 3 GCSI subscores (nausea/vomiting, postprandial fullness/satiation, and bloating) were then calculated.15

2.3 Gastric emptying scintigraphy

The patients referred for a GE test performed a GE scintigraphy according to international recommendations and were classified as normal or delayed GE.9 The results of the GE testing were added retrospectively to the database. The GE scintigraphy was performed within 6 months after, or sometimes before the medical consultation (patients referred after the result of the GE test). Patients were asked to stop treatments that may impact GE 48–72 h before the exam (opioids or prokinetics mainly). Fasting blood glucose levels had to be lower than 2.5 g/L in diabetic patients before the meal ingestion.

The GE scintigraphy was performed after the ingestion of a calibrated meal consisting of two egg whites, and two slices of bread labeled with Technetium 99-m. Emptying of liquids was assessed at the same time after the ingestion of Indium-111 labeled water. Delayed GE was defined by a retention rate of solid food >60% at 2 h, and/or >10% at 4 h.9 The half-emptying time (T1/2) was also reported for solids and liquids. Severely delayed GE was defined by a retention rate at 4 h > 50%, corresponding to Grade 4 according to the consensus for GE scintigraphy.9 Patients who had GE scintigraphy that did not comply with international recommendations (mainly only 2 h recording or even less) were excluded.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The comparison between patients with normal and delayed GE was performed by a Student's t-test, or Welch's test for quantitative variables. A chi-squared test was performed for the comparison between discrete variables. Finally, the correlation between symptoms and numerical values of the GE scintigraphy was performed using a Spearman test.

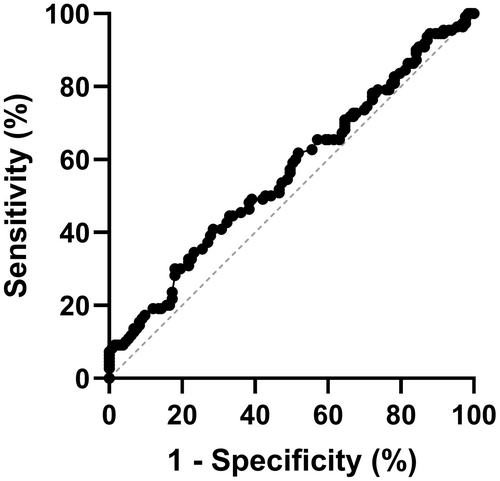

A receiving operator characteristic (ROC) curve was represented for GCSI scores to determine the best predictive threshold for the diagnosis of GP using GraphPad Prism. version 8.0, for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). Sensitivity and specificity were then calculated with this best-chosen threshold.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Clinical characteristics of the cohort

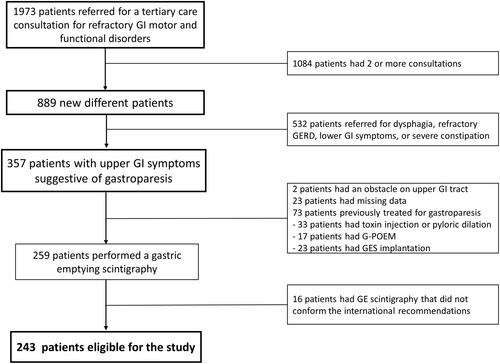

Between February 2015 and April 2021, 334 patients were seen in consultation for upper GI symptoms suggestive of GP and explored by GE scintigraphy. Of these patients, 75 patients had previously received endoscopic or surgical treatment for GP and were excluded. In addition, 16 patients had non-compliant GE scintigraphy and were also excluded (Figure 1). Therefore, the study cohort consisted of 243 patients.

The clinical characteristics of the cohort are described in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 45.5 ± 17.4 years, with majority being women (n = 175; 72% of the population). The most frequent co-morbidities were diabetes (n = 60; 24.7%), previous surgery (n = 50; 20.6%), and systemic diseases (n = 38; 15.6%). The surgical history included anti-reflux surgery (n = 21), lung transplantation (n = 10), esophagectomy for cancer (n = 6), and other pancreatic, or gastric surgery not involving the antrum (n = 13). Systemic diseases included Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (n = 10), systemic sclerosis (n = 7), connective tissue diseases (n = 4), amyloidosis (n = 3), sarcoidosis (n = 3), Parkinson's disease (n = 4), and other genetic systemic conditions (n = 7). The mean GCSI score was 2.93 ± 1.03 with a mean duration of symptoms of 3.4 ± 4.5 years. The two most severe symptoms reported by the patients were early satiation, rated 3.82 ± 1.42, and postprandial fullness rated 3.52 ± 1.49.

| n = 243 patients | |

|---|---|

| Sex: female | 175 (72%) |

| Age (years) | 45.5 ± 17.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 ± 5.2 |

| Chronic cannabis consumption | 4 (1.6%) |

| Chronic opioids consumption | 6 (2.5%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 60 (24.7%) |

| Type 1 | 38 (15.6%) |

| Type 2 | 22 (9.1%) |

| Previous surgery | 50 (20.6%) |

| Systemic/neurologic disorders | 38 (15.6%) |

| No comorbidity | 95 (39.1%) |

| Weight loss (kg) | 7.3 ± 9.4 |

| Duration of symptom evolution (years) | 3.4 ± 4.5 |

| Symptoms | |

| Nausea | 2.80 ± 1.57 |

| Retching | 2.54 ± 1.73 |

| Vomiting | 1.85 ± 1.93 |

| Postprandial fullness | 3.52 ± 1.49 |

| Early satiation | 3.82 ± 1.42 |

| Not able to finish a normal meal | 3.10 ± 1.72 |

| Loss of appetite | 2.63 ± 1.83 |

| Bloating | 3.36 ± 1.64 |

| Abdominal distension | 2.91 ± 1.88 |

| GCSI score | |

| Global score | 2.93 ± 1.03 |

| Nausea/vomiting subscore | 2.39 ± 1.36 |

| Postprandial fullness/satiation subscore | 3.27 ± 1.20 |

| Bloating subscore | 3.14 ± 1.66 |

- Note: Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as numbers and percentages.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GCSI, Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index.

3.2 Results of gastric emptying scintigraphy

GE scintigraphy confirmed delayed GE of solid food in 110 patients, representing 45.3% of the whole cohort. The mean retention rate at 4 h was 27.7 ± 28.8%, and 39 patients had a severely delayed GE, this represented 35.5% of patients with delayed GE. The mean T1/2 for solids GE was 158.0 ± 161.9 min. Liquid emptying was also assessed and showed a mean retention rate of 12.8 ± 15.8% at 4 h. Eighty-one patients had delayed GE for liquids using a retention threshold of 10% at 4 h, among which four patients did not have delayed GE for solids. The mean T1/2 for liquid GE was 60.2 ± 50.4 min.

3.3 Comparison of patients with normal and delayed gastric emptying

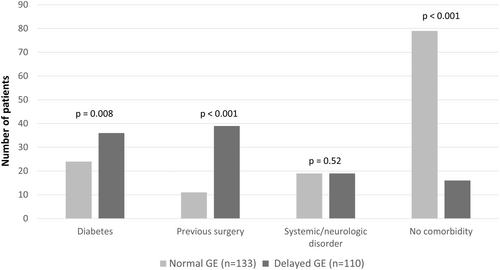

The characteristics of patients with normal and delayed GE are presented in Table 2. Patients with delayed GE had a higher mean age (49.9 ± 17.1 vs. 41.3 ± 16.6 years; p < 0.001), but no difference in the sex ratio was observed (73.5% female vs. 69.9%; p = 0.42) as compared to patients with normal GE. A higher weight loss (9.4 ± 11.8 vs. 5.6 ± 6.6 kg; p = 0.025) was associated with delayed GE. Patients with diabetes or a history of surgery with a higher risk of GP had a higher prevalence of delayed GE (32.7% vs. 18%; p = 0.003, and 34.5% vs. 8.3%; p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2). On the contrary, patients without comorbidity were more likely to have normal GE (59.4% vs. 14.5%; p < 0.001). The proportion of patients with delayed GE results was not different between type 1 and type 2 diabetes (57.9% vs. 63.6%, respectively; p = 0.66). A trend for a higher rate of delayed GE was shown for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, although the subgroup analysis did not reach significance.

| Normal GE (n = 133) | Delayed GE (n = 110) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.3 ± 16.6 | 49.9 ± 17.1 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 93 (69.9%) | 82 (73.5%) | 0.424 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.6 ± 5.2 | 21.7 ± 5.2 | 0.984 |

| Cannabis consumption | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0.637 |

| Opioid consumption | 2 (1.5%) | 4 (3.9%) | 0.284 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 24 (18.0%) | 36 (32.7%) | 0.008 |

| Type 1 | 16 (12.0%) | 22 (20.0%) | 0.09 |

| Type 2 | 8 (6.0%) | 14 (12.7%) | 0.07 |

| Previous surgery | 11 (8.3%) | 39 (35.5%) | <0.001 |

| Systemic/neurologic disorder | 19 (14.3%) | 19 (17.3%) | 0.523 |

| No comorbidity | 79 (59.4%) | 16 (14.5%) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss (kg) | 5.6 ± 6.6 | 9.4 ± 11.8 | 0.025 |

| Duration of symptom evolution (years) | 3.7 ± 4.7 | 3.1 ± 4.2 | 0.405 |

- Note: Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as numbers and percentages. A Student's t-test was performed for comparison of continuous data, and a Chi-squared test or Fischer's exact test was performed for binary data.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GE, gastric emptying.

The comparison of symptoms and the GCSI scores between patients with normal and delayed GE is presented in Table 3. Only the vomiting severity was significantly higher in patients with delayed GE (2.21 ± 1.91 vs. 1.56 ± 1.90; p = 0.008). The global GCSI score was also higher in this group (3.07 ± 1.04 vs. 2.80 ± 1.01; p = 0.045), while other GSCI subscales were not significantly different between patients with normal and delayed GE, as shown in Table 3.

| Normal GE (n = 133) | Delayed GE (n = 110) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea/vomiting symptoms | |||

| Nausea | 2.77 ± 1.53 | 2.82 ± 1.61 | 0.826 |

| Retching | 2.49 ± 1.74 | 2.60 ± 1.71 | 0.622 |

| Vomiting | 1.56 ± 1.90 | 2.21 ± 1.91 | 0.008 |

| Fullness/satiation symptoms | |||

| Postprandial fullness | 3.38 ± 1.62 | 3.66 ± 1.32 | 0.140 |

| Early satiation | 2.99 ± 1.71 | 3.21 ± 1.73 | 0.318 |

| Not able to finish a meal | 3.77 ± 1.54 | 3.87 ± 1.29 | 0.589 |

| Loss of appetite | 2.57 ± 1.85 | 2.68 ± 1.81 | 0.658 |

| Bloating symptoms | |||

| Bloating | 3.22 ± 1.71 | 3.49 ± 1.56 | 0.211 |

| Abdominal distension | 2.68 ± 1.96 | 3.14 ± 1.75 | 0.056 |

| GCSI global score | 2.80 ± 1.01 | 3.07 ± 1.04 | 0.045 |

| GCSI subscales | |||

| Nausea/vomiting | 2.28 ± 1.26 | 2.54 ± 1.46 | 0.141 |

| Postprandial fullness/satiation | 3.18 ± 1.23 | 3.35 ± 1.17 | 0.255 |

| Bloating | 2.95 ± 1.73 | 3.32 ± 1.56 | 0.090 |

- Note: Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Comparison between the two groups was performed using a Student's t-test.

- Abbreviations: GCSI, Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index; GE, gastric emptying.

3.4 Prediction of delayed gastric emptying

The impact of the GCSI score for the diagnosis of delayed GE was then assessed using a ROC curve (Figure 3). The area under the curve was 0.566. The best threshold was set for a GCSI value of 2.875, with a sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 50%. No other value gave a better sensitivity and specificity ratio. The area under the curve was similar for other GCSI subscales, reaching 0.558, 0.537, and 0.555 for nausea/vomiting, postprandial fullness/satiation, and bloating subscales, respectively.

3.5 Comparison between patients with normal and severely delayed gastric emptying

The characteristics of patients with severely delayed GE are presented in Table 4. The mean age (54.3 vs. 41.3 years; p < 0.001) and weight loss (13.1 vs. 5.6 kg; p = 0.031) remained significantly higher in this group of patients, as compared to patients with normal GE. The comorbidities were also significantly different, with a higher proportion of patients with previous surgery (38.5% vs. 8.3%; p = <0.001), and a lower proportion of patients without comorbidity (12.8% vs. 59.4%; p < 0.001). No difference in symptoms or GCSI scores was found between patients with severely delayed GE and patients with normal GE.

| Normal GE (n = 133) | Severely delayed GE (n = 39) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.3 ± 16.6 | 54.6 ± 16.1 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 93 (69.9%) | 28 (71.8%) | 0.997 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.6 ± 5.2 | 23.6 ± 6.0 | 0.252 |

| Cannabis consumption | 2 (1.5%) | 0 | NA |

| Opioid consumption | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (5.1%) | 0.222 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 24 (18.0%) | 11 (28.2%) | 0.179 |

| Type 1 | 16 (12.0%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0.58 |

| Type 2 | 8 (6.0%) | 5 (12.8%) | 0.16 |

| Previous surgery | 11 (8.3%) | 15 (38.5%) | <0.001 |

| Systemic/neurologic disorder | 19 (14.3%) | 8 (20.5%) | 0.330 |

| No comorbidity | 79 (59.4%) | 5 (12.8%) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss (kg) | 5.6 ± 6.6 | 13.1 ± 12.8 | 0.031 |

| Duration of symptom evolution (years) | 3.7 ± 4.7 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 0.141 |

| Nausea/vomiting symptoms | |||

| Nausea | 2.77 ± 1.53 | 2.68 ± 1.68 | 0.695 |

| Retching | 2.49 ± 1.74 | 2.82 ± 1.48 | 0.243 |

| Vomiting | 1.56 ± 1.90 | 2.08 ± 1.87 | 0.115 |

| Fullness/satiation symptoms | |||

| Postprandial fullness | 3.38 ± 1.62 | 3.41 ± 1.46 | 0.140 |

| Early satiation | 2.99 ± 1.71 | 3.13 ± 1.73 | 0.318 |

| Not able to finish a meal | 3.77 ± 1.54 | 3.69 ± 1.42 | 0.589 |

| Loss of appetite | 2.57 ± 1.85 | 2.31 ± 2.00 | 0.658 |

| Bloating symptoms | |||

| Bloating | 3.22 ± 1.71 | 3.36 ± 1.69 | 0.776 |

| Abdominal distension | 2.68 ± 1.96 | 3.31 ± 1.61 | 0.072 |

| GCSI global score | 2.80 ± 1.01 | 2.99 ± 1.08 | 0.370 |

| GCSI subscales | |||

| Nausea/vomiting | 2.28 ± 1.26 | 2.50 ± 1.42 | 0.326 |

| Postprandial fullness/satiation | 3.18 ± 1.23 | 3.13 ± 1.25 | 0.805 |

| Bloating | 2.95 ± 1.73 | 3.33 ± 1.56 | 0.268 |

- Note: Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as numbers and percentages. A Student's t-test was performed for comparison of continuous data, and a Chi-squared test or Fischer's exact test was performed for binary data.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GCSI, Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index; GE, gastric emptying.

3.6 Correlation between symptoms and delayed GE

The correlation between numerical data from GE measurement and symptoms is represented in Table 5. There was no correlation between any symptom and measurement of GE of solids. Only T1/2 of GE of liquids was correlated with vomiting (r = 0.14; p = 0.04) even though this correlation was poor. A correlation between early satiation (r = 0.13; p = 0.04) and abdominal distension (r = 0.16; p = 0.01) was also statistically significant. The correlation between the global GCSI score and subscores is also shown in Table 5. The GCSI scores did not correlate with any measurement of the GE of solids. The best correlation was with T1/2 of GE of liquids and the GCSI score (r = 0.18; p = 0.01).

| Solids | Liquids | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention rate at 4 h (%) | T1/2 (min) | Retention rate at 4 h (%) | T1/2 (min) | |

| Nausea/vomiting symptoms | ||||

| Nausea | r = 0.00; p = 0.98 | r = −0.06; p = 0.40 | r = −0.04; p = 0.63 | r = 0.04; p = 0.55 |

| Retching | r = 0.00; p = 0.99 | r = 0.03; p = 0.63 | r = 0.05; p = 0.51 | r = 0.11; p = 0.09 |

| Vomiting | r = 0.08; p = 0.29 | r = 0.11; p = 0.11 | r = 0.08; p = 0.29 | r = 0.14; p = 0.04 |

| Fullness/satiation symptoms | ||||

| Postprandial fullness | r = 0.03; p = 0.64 | r = −0.01; p = 0.83 | r = 0.09; p = 0.27 | r = 0.09; p = 0.19 |

| Early satiation | r = 0.07; p = 0.36 | r = 0.09; p = 0.19 | r = 0.15; p = 0.06 | r = 0.13; p = 0.04 |

| Unable to finish meal | r = −0.03; p = 0.71 | r = −0.04; p = 0.55 | r = 0.03; p = 0.73 | r = 0.08; p = 0.25 |

| Loss of appetite | r = −0.04; p = 0.63 | r = 0.01; p = 0.90 | r = −0.01; p = 0.91 | r = 0.05; p = 0.43 |

| Bloating symptoms | ||||

| Bloating | r = 0.10; p = 0.15 | r = 0.04; p = 0.58 | r = 0.10; p = 0.19 | r = 0.13; p = 0.06 |

| Abdominal distension | r = 0.14; p = 0.05 | r = 0.10; p = 0.12 | r = 0.17; p = 0.03 | r = 0.16; p = 0.01 |

| GCSI global score | r = 0.10; p = 0.15 | r = 0.08; p = 0.24 | r = 0.14; p = 0.08 | r = 0.18; p = 0.01 |

| GCSI subscales | ||||

| Nausea/vomiting | r = 0.05; p = 0.52 | r = 0.05; p = 0.45 | r = 0.06; p = 0.43 | r = 0.14; p = 0.04 |

| Fullness/satiation | r = 0.02; p = 0.82 | r = 0.02; p = 0.72 | r = 0.10; p = 0.19 | r = 0.12; p = 0.06 |

| Bloating | r = 0.13; p = 0.07 | r = 0.08; p = 0.21 | r = 0.15; p = 0.06 | r = 0.15; p = 0.02 |

- Note: The correlations have been performed using a Spearman test. Significant data are shown in bold.

- Abbreviations: GCSI, Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index; T1/2, half-time of gastric emptying.

4 DISCUSSION

The main results of this study are as follows: (1) 45% of patients explored for upper GI symptoms suggestive of GP had delayed GE confirmed by scintigraphy; (2) patients with older age, higher weight loss, diabetes, or a history of surgery with a risk of GP were more likely to have delayed GE; and (3) the GCSI score was significantly higher in patients with delayed GE, although there was no relevant threshold, and vomiting was the most distinctive symptom.

In the present study, GP was confirmed in 45% of patients with upper GI suggestive symptoms with an objective measurement of delayed GE. An optimal test with a GE scintigraphy was performed on patients, which lasted 4 h and conformed to international recommendations. Thus, 16 patients with a shorter duration of recording were excluded. Indeed, the last meta-analysis by Vijayvargiya et al. highlighted that many studies performed suboptimal measurements, with 19 of 49 GE studies using measurements for less than 3 h or using only liquid meals.18 This led to heterogeneity in the association between symptom assessment and the results of GE tests.18 This rate of delayed GE is similar to another study by Wuestenberghs et al. reaching 45% of patients,19 although other studies reported a slightly lower rate ranging from 25% to 35%.20, 21

Although the measurement of delayed GE is a mandatory condition for the diagnosis of GP, patients with FD might have a slightly delayed GE and remain classified as FD. Whether GP is a part of the spectrum of FD or not remains a matter of debate in the literature. The two entities share many common symptoms, including postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain. Moreover, the study of Pasricha et al. including 944 patients showed high intra-individual variability in the results of the GE test repeated 48 weeks apart.14 The result of GE testing can change in nearly one-third of patients with FD or GP, independently of symptom evolution, and this study assessed that the two diagnoses are interchangeable.14 However, a confirmed diagnosis of GP could impact patients care, especially with the development of new endoscopic techniques, namely, gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy.22 Moreover, recent data suggested that delayed GE had a prognosis impact leading to an increased mortality.23 Thus, the GE test should be performed in patients refractory to medical treatment, in which the result will lead to further interventions. Also, the prevalence of FD reached up to 7.2% of the worldwide population, making it necessary to select the patients that will need an accurate GE measurement.1

The current series did not find any correlation between sex and delayed GE. An older study of 343 patients reported delayed GE to be more prevalent in female patients.24 However, the definition of delayed GE in this study by Stanghellini et al. was based on local mean values, before the publication of international recommendations.9, 24 The recent study by Huang et al. showed results similar to our series with no difference in delayed GE between males and females.21 This was also confirmed by epidemiological studies showing a similar predominance of females among patients with FD and GP, reaching 60% of the population in both conditions.7, 25 Along the same line, epidemiological studies reported that the incidence of GP increased with age, with the mean age at diagnosis being 50.6 years for GP as compared to 43.8 for patients with FD.7, 25 The study of Huang et al. also reported a higher prevalence of delayed GE in their older age group.21

Several studies assessing the correlation between symptoms and GE excluded patients with diabetes.21, 26, 27 In the current study, 60% of diabetic patients had a delayed GE. The prevalence is higher than the reported prevalence of delayed GE in diabetic patients, ranging from 19% to 36%, even though those studies did not only include patients with upper GI symptoms.28, 29 The study by Chedid et al. mainly reported data on patients with Type 2 diabetes, while another study showed that the prevalence of GP was 3 to 4 times higher in patients with type 1 diabetes, which is different from our series where no difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes was found.28, 30 Nevertheless, two studies showed that diabetes was associated with a higher prevalence of delayed GE in patients with upper GI symptoms referred for GE measurement.16, 19 In the study of Wuestenberghs et al., diabetes was the only condition associated with a higher prevalence of delayed GE in the multivariate analysis.19 Patients with a previous history of surgery also had a significantly higher prevalence of delayed GE reaching 78% of the patients. We only reported previous surgeries associated with a higher risk of GP, including fundoplication, lung transplantation, and Ivor Lewis surgery, which certainly leads to a selection bias. However, the reported prevalence of diagnosed GP after lung transplantation or fundoplication is higher than in the global population, reaching 10.7% and 3.4%, respectively.31, 32 Therefore, our results were in line with these data. Finally, in the “idiopathic” group without comorbidities, the rate of confirmed delayed GE was only 17%.

The correlation between symptoms and delayed GE has been assessed in several studies with conflicting results. Two studies published by Stanghellini et al. and by Sarnelli et al. showed that postprandial fullness and vomiting were associated with delayed GE with odds ratios (OR) of 4.04 [1.30–12.54] and 2.65 [1.62–4.35] for vomiting, respectively.24, 33 The meta-analysis by Vijayvargiya et al. found that nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiation/fullness were significantly associated with GE with the highest OR of 2.0 [1.6–2.7] for vomiting.18 On the contrary, several studies did not find any association between symptoms and the results of GE.16, 19, 26 In the current study, a higher vomiting score was reported in patients with delayed GE. This symptom seems to be the one that correlated with the results of GE.18, 24 This is also highlighted by the recent consensus that identifies nausea and vomiting as cardinal symptoms for the diagnosis of GP, and as key symptoms to define the “gastroparesis-like symptoms.”21, 34 These symptoms have also been excluded from the definition of FD according to the Rome IV criteria.3

Another differentiating criterion in the current study was the higher weight loss in patients with confirmed GP. Previous studies did not show that GP leads to weight loss, a recent study even showed that only 20% of patients with idiopathic GP experience weight loss at 48 weeks.35, 36 Few studies assessed the correlation between GE results and weight loss, but the study by Carbone et al. also did not show any difference in weight loss between patients with normal and delayed GE.27 Nonetheless, the last study published by Huang et al. showed that patients with “gastroparesis-like” symptoms had lower body mass index, supporting the results of the current study.21

Several factors have been put forward to explain the poor association between symptoms and GE measurements. A first explanation could be the intra-individual variability as highlighted by the study of Pasricha et al.14 Another study by Carbone et al. simultaneously assessed symptoms and GE measurement, at the same time, and showed that symptom association remained poor, and only nausea was higher in patients with delayed GE.27 This study did not assess vomiting symptoms, but one might expect that nausea during the test could be associated with later vomiting. Another hypothesis has been that only severely delayed GE should be considered and that a new threshold for the diagnosis of GP should be considered, as pointed out by the recent American consensus on GP.6 This is supported by two studies that showed that patients with severely delayed GE had different symptom characteristics as compared to normal or mildly delayed GE.19, 36 However, including only patients with severely delayed GE, we did not find a higher association with symptoms, but only abdominal distension was more severe in patients with severely delayed GE. Other studies used the T1/2 value rather than the retention rate at 4 h and showed that T1/2 was less sensitive but more specific for the diagnosis of GP.37 In the current study, we did not find a better correlation between symptoms and GE measurement for solids using T1/2 values or gastric retention rate. Surprisingly, the correlation with symptoms was better using T1/2 for liquids.

The physiology of liquid emptying is different from solids. Water bypasses the stomach and crosses through a functional tunnel directly toward the duodenum, within 10 min after meal ingestion.38 Solids must first be reduced to small size particles of 2-3 mm, then the antroduodenal coordination will lead to GE of solids which takes more time.38 GP has been defined as the delay of GE for solids according to international recommendations, but one series showed that 20% of patients could have delayed GE for liquids with normal GE for solids.39 Therefore, we do believe that the measurement of liquid GE could provide an added value. Indeed, several studies showed that early satiation was associated with liquid but not solid GE measurements.33, 36 Satiation has also been shown to be related to the drop in intra-gastric pressure after food intake, induced by gastric accommodation.40 Thus, further studies are still needed to assess whether measurements of liquid emptying could be helpful and might be related to gastric accommodation or not. Indeed, GE is not the only pathophysiological mechanism implicated in symptoms and this is also a main factor to explain the lack of correlation between the results of scintigraphy and symptoms. Gastric accommodation and hypersensitivity to gastric distension have been shown to play a role in both patients with FD or GP.21

Finally, this study aimed to assess the impact of the GCSI score as a diagnostic tool. We showed that the overall symptom score was slightly but significantly higher in patients with delayed GE (3.06 vs. 2.80; p = 0.05), even though this difference did not seem to be clinically relevant. In agreement with a previous study from Cassily et al., we did not find any cut-off with a high sensitivity and sensitivity ratio.16 The GCSI score includes several symptoms that are not specific to GP, including loss of appetite, bloating, or other dyspeptic symptoms. Thus, this score can help with the follow-up of GP patients who may complain of all of these symptoms. However, a selection of more specific symptoms and factors for the diagnostic impact seems to be necessary, as is currently done with the evaluation of the “gastroparesis-like” symptoms.21

Our study has several limitations. This is a monocentric study performed in a tertiary center, which might lead to a selection bias with more severe patients. However, most of the studies in the literature assessing symptoms and GE have been performed in tertiary centers making our results comparable. Some patients had a long delay between clinical assessment and performance of the GE scintigraphy. Therefore, we aimed to limit this duration between clinical assessment and GE scintigraphy to 6 months, and we excluded patients treated with endoscopic procedures that might impact GE results. The retrospective design is also a limitation, although the result of the GCSI scores were collected prospectively, which reduces the risk of recall bias. Only the results of the GE test, which remains an objective measurement, were collected retrospectively. Nevertheless, a standardized GE measurement technique that conforms to international recommendations was performed, with the evaluation of solids and liquids GE. The absence of standardized criteria to refer patients for a GE test can lead to another selection bias since this decision was made according to the clinician's decision. Moreover, there was no evaluation of symptoms not included in the GCSI score, especially abdominal pain which is a very common symptom in GP.41 However, this symptom is not specific to GP and is also widely associated with the epigastric pain subgroup of FD. Finally, our study included very few patients who admitted to consuming cannabis and opioids, probably due to a reporting bias. Indeed, the opioid use of 2.5% of our population differs from those of other studies which can reach 41%, especially in American studies.42

5 CONCLUSION

This study shows that more severe vomiting symptoms, higher weight loss, and the presence of diabetes or a history of surgery with a risk of GP should make the clinician consider GE testing, especially if the results will lead to different treatment or impact the patients care. The GCSI score alone does not allow the diagnosis of GP, and no cut-off helped decide whether a GE measurement should be performed or not. Further studies are needed to determine whether composite scores including these differentiating factors could be developed and have a diagnostic impact to better select patients for GE testing.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CS collected and analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. RL, HD, and MD contributed to the acquisition and collection of data. HD critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. BC contributed to the design of the study, contributed to the acquisition of data, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. HS contributed to the design of the study, did the statistical analysis, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.