A Thematic Analysis of Intensive Care Unit Diaries Content

Funding: This work was supported by grant from the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation (grant number 8-2014-07) to Dr. Blouw. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation grant number 333252 (to Dr. Sareen).

ABSTRACT

Background

Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries are an intervention used in the critical care setting to provide patients with a cohesive narrative of their ICU stay and can have a positive impact on patient and family outcomes. Few studies have examined the content of the diaries as written by family members and healthcare staff, and further information on this is important in understanding how and why diaries can be of benefit.

Aim

Content analysis of diaries completed in a medical-surgical ICU within an academic medical centre in Manitoba, Canada.

Study Design

This was a secondary qualitative analysis of ICU diaries that were completed in 2014–2016 as part of a prior pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) with adult patients, admitted for more than 72 h and ventilated for more than 24 h. We used a reflexive thematic analytic approach to qualitative analysis, resulting in major themes and subthemes of the diary content.

Results

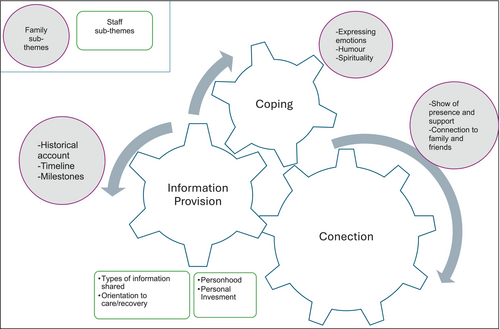

Thirty diaries were analysed. Themes identified (1) Connection (staff subthemes: personhood and personal investment, family subthemes: connection to patient and connection to family/friends), (2) Information provision (subthemes: type of information shared, how information was shared and family-specific information sharing) and (3) Coping (subthemes: expressing emotions, use of humour, spirituality).

Conclusions

This is the first study exploring the content of ICU diaries in a North American context and adds to the existing small body of literature demonstrating how families and healthcare staff use diaries. The findings are beneficial in designing future diary programmes, as understanding how diaries are used in a real-world setting can guide future implementation and resource allocation. ICU diaries are an increasingly common tool used in ICU settings to provide patients with a narrative of their critical illness. Diaries conveyed a connection between healthcare professionals, family and patient, were used to provide information and appeared to be used to help family members cope.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

This study provides information regarding how ICU diaries are used by healthcare providers and what information is conveyed, which is useful in guiding future implementation as this intervention becomes more widespread (e.g., utilization, feasibility and instructions).

Summary

-

What is known about this topic

- ○

ICU diaries are commonly used tools in ICUs and show promise in reducing symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress following ICU discharge.

- ○

Qualitative analysis of diary content is limited; these small studies from European ICUs broadly demonstrate that diaries are used as a way to share information, connect with patients and communicate medical and emotional content.

- ○

-

What this paper adds

- ○

This thematic analysis demonstrates that ICU diaries are used to facilitate connection and information provision and are a method of coping for caregivers (healthcare providers and family members) while the patient is in ICU.

- ○

The findings provide context and a framework for how families and healthcare providers in a North American setting work together to care for patients in the ICU via diaries.

- ○

1 Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries are a bedside notebook, completed by family members and the medical team, while a patient is in the ICU. Diaries serve to provide the patient with a narrative account of the ICU stay, addressing gaps in memories or traumatic/delusional memories (icu-diary.org) [1]. Understanding how diaries are best implemented, the benefits of diaries with regard to patient and caregiver mental health and bereavement following ICU and practical considerations for implementing diaries has been a research focus. There is comparatively little research exploring the contents of the diaries themselves.

2 Background

Analysis of diary contents can be helpful in understanding the utility and possible benefits of the diaries. How diaries are written by families and the health care team can impact logistical aspects of the intervention, such as how the diary is best completed and by whom, as well as outcome variables, including patient, family and health care provider mental health, satisfaction with care and use of the diary. To our knowledge, a limited number of studies have analysed diary contents using qualitative methods. In one recent thematic analysis of 32 ICU diaries written by family caregivers in an Italian setting, the authors described 7 main themes, with associated subthemes, in the diaries. These included: future plans and memories, professional caregivers of the patient, the love surrounding the patient, patients' clinical progression and the passage of time, what happens outside the patients' life, usefulness of the diary and communication regarding the likely death of the patient [2]. Earlier work by Roulin and colleagues included content analysis of eight ICU diaries, with the goal of understanding benefits to patients and families. The overall theme of the diaries was noted to be ‘sharing’, with themes of sharing the story, sharing the presence, sharing feelings and sharing through support [3]. Using a narrative approach, Egerod and Christensen analysed 25 Danish ICU diaries. These diaries were written by bedside nurses. They identified three stages in the temporal narrative of the diaries. The first was ‘crisis’ – describing the many medical procedures being done in the early stages of admission. The second stage of the narrative was ‘turning point’, often associated with changes in status or treatment, such as extubation. The third stage in the narrative was ‘normalization’, in which the patient is recovering, and who they are as a person becomes more known [4]. In summary, diaries have served as a means to integrate various types of information and serve a connective purpose during the course of an ICU stay.

3 Methods

3.1 Aim

Diaries can be beneficial in assisting patients and families understand and integrate their ICU experience. There is considerable variability in how diaries are implemented and limited research exploring the content of the diaries themselves. This has potential implications for the feasibility and efficacy of the intervention. As such, the aim of the current study is to evaluate the contents of ICU diaries completed at 10-bed medical-surgical ICU in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

3.2 Study Design

In order to achieve our aim of evaluating the content of ICU diaries, we conducted a secondary qualitative analysis of bedside ICU diaries which were written in the context of our group‘s previously published pilot randomized controlled trial of ICU diaries [5] In this RCT study, all staff and patient bedside visitors were invited to complete daily diary entries. In preparing individuals to write in the diaries, ICU staff were invited to brief educational sessions about the purpose and nature of ICU diaries, facilitated by a research nurse (NM). Sample diary entries were provided with each bedside diary. Patient caregivers/visitors were provided with a written instruction sheet that was appended to the front of the diary (this was also accessible to healthcare staff). See Appendix A for these instructions.

After each entry, staff and patient caregivers were asked to complete a brief survey stating their role on the team and the burden/feasibility of completing the diary entry.

3.3 Setting and Sample

All diaries completed for a pilot RCT [5] were evaluated in the current study (N = 30). The diaries were completed between June 2014 and July 2016. Per the RCT, diaries were completed for patients in a 10-bed mixed medical-surgical at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Winnipeg, MB, Canada. At the time the data were collected, care on this unit involved a 1:1 patient to nurse ratio.

3.4 Data Collection Methods

Patients were eligible for enrolment if they were mechanically ventilated, older than 17 years and able to understand both verbal and written English. Enrolment occurred within 72 h of the current ICU admission, with ICU length of stay predicted to be > 72 h and duration of mechanical ventilation predicted to be > 24 h by the ICU treatment team at the time of enrolment. ICU patients were excluded if there was no caregiver/family available, they had a terminal illness with life expectancy of less than 6 months, pre-existing cognitive impairment or the reason for admission was suicide attempt/intentional toxic overdose, meningitis/encephalitis, status epilepticus, anoxic encephalopathy, traumatic brain injury or coma due to another aetiology. Consent for study enrolment was provided initially by a proxy/substitute decision maker as all eligible subjects were mechanically ventilated with high rates of incapacity to provide consent. Subsequent consent to continue in the study was provided by each subject regained capacity. Consent was obtained to use data/content in the diaries in future analysis and research.

Patients were randomized to one of four arms: (1) Treatment as usual (TAU), (2) ICU diary, (3) Psychoeducation and (4) ICU diary + psychoeducation. Diaries of patients in the ICU Diary and ICU Diary + Psychoeducation arm were used in the current analysis. In the psychoeducation intervention, participants were provided with a brochure at hospital discharge, outlining common post-ICU mental health difficulties and local resources for support. As this was given after diaries were completed, no diary content differences in the diary vs. diary + psychoeducation arm would be expected. Demographic characteristics of ICU patients whose diaries were analysed in the current study are listed in Table 1. As patients (or family members in the case of patient death) were given the original diaries at hospital discharge, photocopies of the diaries were used in the analysis. In addition to analysing the content of diaries, several quantitative descriptors were evaluated to contextualize the diaries, including number of entries per diary, median number of diary pages and relationship of the writer to the ICU patient.

| Diary (n = 15) | Diary + Psychoeducation (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n, %) | 7 (47%) | 11 (73%) | |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 59.3 (15.5) | 55.7 (14.0) | |

| Acute illness characteristics | |||

| SOFA score within first 24 h of admission (M, SD) | 9.1 (3.7) | 8.2 (4.8) | |

| Primary reason for admission (n, %) | |||

| Respiratory failure | 11 (73%) | 10 (67%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 3 (20%) | 2 (13%) | |

| Sepsis | 1 (7%) | 3 (20%) | |

| Sedation use duration (days) | |||

| Duration of continuous sedation | 5.0 (2–7) | 5.0 (3–10) | |

| Duration of continuous benzodiazepine | 2.0 (0–6) | 2.0 (0–6) | |

| Duration of continuous narcotic | 5.0 (2–7) | 5.0 (2–9) | |

| Duration of continuous propofol | 1.0 (0–3) | 3.0 (0–5) | |

| Ventilator duration (days) | 7.0 (3–11) | 6.0 (4–11) | |

| Coma duration (days) | 4.0 (0–7) | 4.0 (1–5) | |

| Delirium duration (days) | 0.0 (0–3) | 2.0 (1–5) | |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 9.0 (7–13) | 11.0 (6–18) | |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 21.0 (12–61) | 23.0 (9–48) | |

| ICU mortality (n, %) | 2 (13%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Hospital mortality (n, %) | 2 (13%) | 2 (29%) | |

3.5 Data Analysis

Photocopied diaries, written in a 5-in. by 7-in. ruled notebook, were de-identified and analysed according to reflexive thematic analysis [6, 7]. This approach aligned with our objective of understanding the content described by family members and medical staff within the ICU diaries. Two qualitative analysts coded all diaries independently, and regular coding meetings with all co-authors took place following a collaborative approach designed to capture a rich and reflexive interpretation of the data. The research team included two clinical psychologists, two critical care physicians, one critical care research nurse and one psychiatrist. One coder had expertise in qualitative methodology, and the lead researcher, who assisted in refining the thematic map, had clinical expertise with the psychological impacts of critical illness and caregiving. We followed six stages of thematic analysis [6, 7] including: (1) Data familiarization, (2) Generating initial codes, (3) Search for themes, (4) Reviewing themes, (5) Defining and naming themes and (6) Producing the report. In line with the assumptions of reflexive thematic analysis the subjectivity of researchers was reflected upon via coding memos/journals, individual immersion in the data followed by collaborative, multidisciplinary discussions of findings, with breaks to process and reflect on identified themes, and ongoing acknowledgement and discussion of how our differing clinical and research backgrounds influenced our perspectives.

3.6 ICU Diary Characteristics

There were a total of 198 diary entries across the 30 diaries. The median number of diary pages written per diary was 14 (range 5–89). The median number of diary entries written per diary was 6 (range 1–20). The majority of entries were written by nurses (98, 49.5%), followed by family members (78, 39.4%), physicians (12, 6.1%), allied healthcare professionals (6, 3%), friends (4, 2%) and others (6, 3%).

3.7 Ethical and Research Approvals

This teaching hospital is affiliated with University of Manitoba. This study was approved February 3, 2014 by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS17016/H2013:460). Patients had provided consent for their diaries to be analysed for research purposes.

4 Findings

4.1 Thematic Framework

We developed three main themes from our analysis of the diaries, including (1) connection, with subthemes for staff of personhood and personal investment, and subthemes for family of connection to patient and connection to family/friends; (2) information provision, with subthemes of type of information shared, how information was shared, and family-specific information sharing; and (3) coping, with subthemes including expressing emotions, coping through use of humour and coping through spirituality. Sub-sub-themes were also identified and are outlined with bullets in Table 2. Below we identify quotes that come from staff or family members across diary entries. A thematic diagram of ICU diary content is provided in Figure 1.

| Theme | Staff | Family |

|---|---|---|

| Connection | Personhood | Connection to patient |

|

Show of presence/support | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Personal investment | Connection to family/friends | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Information provision | Type of information shared | Historical account/listing events |

|

Timeline | |

|

Communication of milestones | |

|

||

| Orientation to care/recovery | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| How information was shared (across family and staff) | ||

|

||

|

||

| Coping | Expressing emotions | |

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Coping through use of humour | ||

| Coping through spirituality | ||

5 Connection

In their diary entries, both healthcare staff and family members formed and maintained connection to the patient through their writing. In addition to maintaining connection to the patient, family members also connected with other family members/friends throughout diary writing. Staff and family members were also able to reference each other in their writing, demonstrating to the patient the connection of the staff and their family as collaborative team members in their care.

5.1 Staff

5.1.1 Personhood

Staff demonstrated their desire/attempts to learn about the patient as a person and understand aspects of their pre-illness self. One nurse wrote “My name is (name). I am the nurse looking after you today. I have looked after you before. I spoke with your wife (name) today and she told me you were a 70's rock fan and your favourite band is the same as mine (name of band). Just to let you know they are re-uniting this spring. Keep on rockin (patient name).” [01-37]. Staff communicated with empathy, acknowledging the emotions and experience of the patient. For example, a nurse wrote “While the tube is in your mouth we have to clean your mouth often, using foam swabs and toothbrushes. You hate it very much. But we have to do it so you don't develop a lung infection.” [01-38] Another wrote “Today you were frustrated because you were hungry. We were able to give you some clear fluids at lunch which made you a little happier.” [01-03]. One of the ICU physicians commented “You have been more awake today and it seems like you are trying to tell us things but we can't always figure out what. It must be very frustrating” [01-19]. Staff further established the personhood of patients through the diaries by referencing the care being provided that occurred beyond just the medical needs of the patient. A nurse wrote to a patient on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, “I braided your hair because I do not like when hair gets matted!!” [01-40]. This was then noted by the patients' family members, who said in a later entry “(Name) the nice nurse that braided your hair is working tonight and [I] thanked her for what she did” and “Your overnight nurse (nurse name) braided your hair last night and I was very surprised and appreciative that she did that for you”. [1-40] Staff referenced the involvement of the patient's family, to let them know who was visiting and how their family was contributing to their care. As an example, one nurse said “Your daughters are doing an amazing job looking after you and helping us to know what you need – since you seem to be the strong, silent type.” [01-23].

5.1.2 Personal Investment

Staff demonstrated their investment in the patient's care and overall experience in the ICU in several ways. Staff expressed hope for the patients' recovery as well as commented on their strength. For example, a nurse wrote on the morning of a patients' planned pacemaker insertion, “I am hoping everything goes well for you and I am back tonight, I'll get to see how you made out. You've come a long way! Keep it up!!” [01-17]. Staff further demonstrated their investment in care by expressing an understanding of the impact of the ICU stay on the patient, and describing their attempts to increase the patients' comfort. They also expressed concern for patients' discomfort. For example, one nurse said “I also discovered that you were not a fan of when I suctioned (removed fluid or phlegm) from your breathing tube! I apologize! Unfortunately, this is required as it helps keep your lungs clear and allow oxygen to go in and out of your lungs easily” [01-09] and, “Unfortunately we have you on a fluid restriction now because we are still not sure if your kidneys have fully recovered yet. I feel badly restricting you because you're always so thirsty!” [1-23] Regarding upcoming extubation, one of the nurses commented, “I know you'll like this, as it was the only thing giving you any trouble last night.” [01-15]. Staff commented on what they were doing to mitigate discomfort. For example, following a sedated patients' abdominal surgery, a nurse wrote, “I am going to assume you are having pain and will give you extra pain medicine. I want to see you comfortable and to help you heal and recover and so I will do whatever I can for that goal. I am here for you (patient name) and want to see you get better.” [01-25].

5.2 Family

5.2.1 Connection to Patient

Family members connected to the patient by showing presence and support, noting who visited them and for how long, as well as passing on messages from other family members. Family members described how they contributed to the patients' wellbeing. For example, one family member wrote, “I talked to you about (name) and (name) and read you a few Facebook posts. I was very happy to see you respond today. I also applied moisturizer cream to your hands, feet and face. Also chapstick to your lips.” [01-38]. Family members also used the diary to connect to life outside the ICU and the continuing of their relationship with the patient, noting events that were happening in the world or the family, for example “It's your birthday tomorrow, yyyaaayyy.” [01-37]. They also used the diary to connect to normalcy and day-to-day events “the weather was kind of cool this morning when I walked here” [1-41]. Family members also expressed hope for connection back from the patient, writing things like, “I thought yesterday was the best day of my life, when you woke up and looked at us and knew who we were.” [01-22]; “I said I love you and I could see in your eyes that you said it back.” [1-29].

5.2.2 Connection to Other Family/Friends

Family members also used the diaries as a way to connect and communicate with other family members. For example, one family member commented on alarms going off, and in the next entry, another family member joked that the prior writer had been setting off the alarm. Additionally, diary entries touched on relationship repair within families that occurred as a consequence of the hospitalization, “Even a bigger miracle is Grandma's change in attitude towards us. She called us to thank us for supporting you and especially (name). Miracle of miracles!” [1-23].

5.2.3 Connection to Staff

Just as staff entries in the diary supported the personhood of the patient, families likewise demonstrated personal connection with the staff and a desire to let the patient know they were being well cared for by staff, “You have a wonderful nurse (name) who really cares about you. She's taking very good care of you.” [01-37].

6 Information Provision

The diary was used as a vehicle for both staff and families to share medical information with the patient. The first entry always included a timeline of events leading to the ICU admission, written by the study research nurse (NM) or another research staff member. Staff diary entries under this theme focused on situations in which patients may have experienced disorientation or delirium. For example, “You are on medication to paralyze you because your lungs are really sick” [01-37] “You're still pretty tired, pretty sleepy and a little bit confused; the term we use is “delirious.” This is normal. Hopefully it will start to clear up in a day or two.” [01-38], “We still have to keep you on isolation so we are all wearing yellow gowns, masks + gloves.” [01-41]. Staff and family members used the diaries to deliver updates regarding medical procedures and recovery milestones, such as listing blood pressure, medications, sitting up, opening eyes. Staff communicated medical information in clear language, with a positive tone. For example, one physician wrote, “This was a good day for us, from a medical perspective.” [01-54].

7 Coping

Family member coping was a third thematic dimension evident in the process of diary writing. Diary writing was most often focused on the patient; however, at times, family members used the diary to express and cope with their personal experiences throughout the patient's illness. For example, despite the instructions, one spouse caregiver wrote entries as if it were her personal diary, detailing her own difficult experience.

7.1 Emotional Expression

Families used the diaries to express messages of hope, love and gratitude. For example, “Hi Dad! I am sitting here watching you and I am so inspired by your strength. You are determined to win this battle.” [01-23] and “There you were, opening your eyes, holding my hand, most of the machines gone. I feel overjoyed with relief, tears flowing freely and thanking God for your recovery. I'm still shaking with joy. I still love you and cannot wait to see you at home and bugging everyone like you do so well.” [01-22] Conversely, families expressed the emotional challenges experienced in the ICU, noting both what they found personally difficult as well as empathy for patient difficulties. For example, “I find it hard to go home at night…With a torn heart I will go home tonight to rest.” [01-42]. “It is very frustrating not being able to help and just sitting there watching him. Helpless feeling.” [01-49]. “seeing you hooked up to what looks like the flippin' space station freaks me out.” [01-40].

7.2 Acknowledgement of Death/Decision Making

Rarely, family entries in the diaries reflected the life and death nature of the ICU and the struggles families faced around this “It has been a bad few days, approached by 2 Doctors telling me that they don't think he will make it out of here…The Doctors want us to decide if we should revive you if you stop breathing. I can't make that decision on my own.” [01-49]. Occasionally, the diary was used after the death of the patient to express grief “We will miss little sister…I love you we all love you…I will see you soon, R.I.P” [01-34].

7.3 Finding Meaning Through Humour

Families also appeared to find meaning in using the diary, coping with humour and sarcasm as a way to process the difficulties associated with the ICU stay. They seemed to use the diaries to write to the patient about the difficulties faced, in a light hearted way. For example, one family member wrote “don't do this shit again, for a while please. I need some recoup time” [01-51] and “You know Dad, if you wanted me to come visit you could have just asked!” [01-23] and “time to get your butt out of here” [01–09].

8 Discussion

The aim of this paper was to describe the content of ICU diaries written by ICU staff and patients' family members to better understand how the diaries were used. ICU diaries are a newer intervention, have not been standardized, and may have significant variability in implementation across sites and countries. Though there are frameworks for implementation (e.g., [8, 9]) and instructions for completion (icu-diary.org), there has been little in-depth analysis of the ultimate contents of the diary, which is important in understanding their utility in assisting patients and families following the ICU experience. In reviewing the diary contents in the current study, diaries broadly included themes of connection, provision of information and a way of coping with a difficult situation.

With respect to connection, diaries provided space for staff to acknowledge the patient as a person, demonstrate deep caring for their wellbeing and comfort, and reinforce the role of the family in the patients' care. The personal connection that staff had to patients was evident in their diary entries. Establishing and connecting to the personhood of the patient has critically important outcomes in healthcare for both medical and psychosocial domains [10, 11]. Health care workers who are able to connect with patients on a human level tend to not only have better patient-related outcomes, but also experience less professional burnout [12, 13]. This becomes more challenging in the context of the ICU, in which patients are often unconscious and unable to verbalize their needs or aspects of their selves that they wish to be seen. Our study showed that diaries are one way that health care staff can establish such a connection. Further, ICU survivors often have little memory of their hospitalization or have very disturbing and at times delusional or hallucinatory memories [14]. They may feel they have lost days, weeks or months of their lives, untethered to family and friends and their normal routines [15]. The diaries provided a connection to family—both through family written entries demonstrating ongoing connection to the patient, and staff entries emphasizing the families role in the care of the patient. This appeared to be bidirectional, with family members using the diaries to comment on the quality of care being provided by staff. The diaries thus seem to reflect a tangible example of how staff and families together care for patients, in line with best practice guidelines [16, 17].

The diaries provided an important avenue for both staff and family members to provide information about what happened to the patient medically. Theoretically, this is an essential function of the diaries in the context of preventing adverse mental health outcomes associated with the aforementioned false memories of the ICU. ICU survivors have high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e.g., [18]), and for the majority, the traumatic event(s) is not the responsible illness or hospitalization per se, but the false memories occurring in the context of delirium (e.g., [19]). These memories can be extremely vivid and frightening and are extremely difficult for survivors to reconcile. Empirically supported treatments for PTSD focus on integration of memories that are fractured as a result of the trauma and thus associated with intrusive symptoms that characterize the disorder (see [20] for a review of evidence-based psychological treatment for PTSD). Though this is accomplished in different ways in various treatments, the ICU experience (like some other medical traumas) is unique because of the typically high levels of dissociative experiences and presence of false memories (e.g., [21, 22]). As such, ICU diaries are thought to provide context to false memories by providing a realistic narrative of what happened to the patient [23]. Anecdotally, in treating PTSD in medical trauma survivors, we (MK) have found that developing a list of disturbing false memories and reconciling these with a review of the patient chart is a profoundly healing exercise and is associated with significant drops in PTSD symptom scores. However, this is likely not a scalable intervention to manage the pervasive distress these patients experience. As such, diaries can be a way to prevent or mitigate PTSD symptoms by providing a cohesive narrative in patient-centred language [5, 24].

The diaries also provided a place for family members to use various strategies to cope with the difficult situation. Expressive writing is a well established intervention to mitigate stress [25]. Though writers were instructed to keep entries factual and focused on the patient (i.e., the purpose was not for the family members emotional expression), subthemes related to the expression of emotion, finding humour and communication directly to the patient suggest that family members use the diaries as a method of coping. As such, writing in the diary seems to not only have the potential benefit for patients but also for their caregivers Family members of ICU patients often feel powerless [26] despite the development of best practices for ICU care that involve the family [16]. Writing in the diary is an active way that family members can feel that they are “doing something” for the patient, at times when they may feel they can do very little [27, 28]. The above themes of connection, information provision and coping are consistent with prior studies examining the content of diaries [29].

9 Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the study include the first evaluation of ICU diary contents in a North American context. This has practical importance in understanding how instructions for use of the diaries translated into how the diaries were in fact used by staff and family caregivers. The diaries indeed included the primary purpose of information provision, allowing for the potential for patients to reconcile difficult memories of their ICU experience. Additionally, analysis of the diary contents provides novel information regarding how participating in the intervention may indirectly benefit staff and family members by providing an avenue to further connection with the patient and process or cope with stress. There was consistency in the level of acuity of patients who received diaries, as all were ventilated for at least 72 h in order to be part of the original RCT from which the current diaries were completed. As discussed in our prior paper [5], the diaries were well received by staff and family members alike, suggesting a low burden of the intervention.

The study must be viewed in the context of its limitations. We noted that the diaries in the current study ended abruptly. It would be helpful in future research or clinical implementation to include in the instructions to write a closing entry before ICU discharge to provide a sense of closure. A relatively small number of diaries were available for analysis, and as such, the results of the study may not be generalizable. There was a large range in the number of entries, likely reflecting diverse family situations and care needs of the patient. Further, because the diaries analysed in the current study were created in the context of a pilot RCT that had goals outside of the current paper, certain information that might have been helpful to contextualize the current findings (such as family structure, socioeconomic variables, details about the family members writing each entry, years staff had been working in healthcare) was unavailable. Further, the Canadian context may not be generalizable to other centres. These diaries were completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when our ICU's had 1:1 nursing ratios. This provides more intimacy in care and likely more time to complete the diaries than may be available in places with higher staff to patient ratios. However, there are ongoing strains in our public health system, which may be less facilitative of such an intervention compared to countries that implement this intervention more routinely (e.g., Denmark, France). Ongoing understaffing and staff burnout, and illness severity and mental health sequelae in COVID-19 mean that ICU diaries and their potential impact could look quite different in the post-pandemic ICU environment [30]. Relatedly, the length of time from when these data were collected and the current research is significant. This reflects limitations on the teams' research time, which was exacerbated significantly by clinical demands during the pandemic.

10 Implications and Recommendations for Practice

The present study informs the small but growing literature around ICU diaries by providing a detailed framework of how diaries were completed by staff and family caregivers in our Canadian ICU. Diaries were for the most part completed per instructions given and provided a narrative account to patients about their ICU stay. Additionally, both staff and family members connected to the patient through the diaries, and family members used the diaries as a way to cope with the challenging experience of having a loved one in ICU. The study has practical implications for the implementation of diary programmes. It may be helpful to have a more structured framework for diary entries (e.g., a fill-in-the-blank section followed by space for open ended writing), to ensure medical information is included each day. This could help standardize the volume and content of entries to better facilitate the goal of providing a cohesive narrative of the medical aspect of care. Research into the implementation and efficacy of ICU diaries is ongoing. Inclusion of qualitative analysis of diary contents, in addition to long-term outcomes (e.g., on patient, family and/or staff mental health) would be an added benefit in such studies, to determine which ‘ingredients’ are optimal for an ICU diary.

11 Conclusion

ICU diaries are an increasingly common tool used in ICU settings to provide patients with a narrative of their critical illness. In our setting, diaries conveyed a connection between the writer and patient, were used to provide information and appeared to be used to help family members cope. These findings provide a useful framework for future research into the implementation of ICU diaries.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved February 3, 2014 by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS17016/H2013:460) and the St. Boniface Hospital research office.

Consent

Written consent for publication of this study was obtained from patients/next of kin. The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly. Due to the sensitive nature of the research, supporting data (diary content) are not available.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Jitender Sareen is a consultant for UpToDate. No other conflicts of interest to report.

Appendix A: ICU Diary Instructions

Patients who have had a stay in ICU often have little or no memory of their ICU stay. Their memory for this time can be affected by the illness itself or the sedative drugs we give to our patients to keep them comfortable. Patients may also remember nightmares or hallucinations from this time that can be very frightening.

Although doctors and nurses explain to patients why they were admitted to ICU, patients often forget what we have told them. Research has suggested that patients can become stressed and anxious when they do not fully understand what has been wrong with them. To help patients understand more about their illness and ICU stay the staff have introduced patient diaries. A diary has been shown to reduce stress in patients after they are discharged to the wards and in the months after their stay.

A patient diary has been started for your relative. The nursing staff will make diary entries to explain what has brought the patient to ICU, what is wrong with them and how they are progressing. Some patients may also have had photograph(s) taken for their diary.

We would encourage you to write in the diary, to pass on your messages to the patient or to tell them news from home that they would like to hear. When writing in the diary, please avoid using any language that could cause offence, for example, swear words, to the patient or others who may read the diary afterwards.

Your family member's diary will be kept at the bedside in ICU. You just need to ask the nurse looking after your relative if you would like to make a diary entry.

Once patients are well enough to look after their diary, they are allowed to keep it if they wish.

Please remember that the diary is hospital property until handed over to the patient after signing a consent form.

Diaries must not be taken away from the bedside by family members.

If you have any questions about patient diaries, please do not hesitate to ask the nurse looking after your relative.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.