Use of nursing care bundles for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in low-middle income countries: A scoping review

Abstract

Background

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a significant concern in low-middle-income countries (LMICs), where the burden of hospital-acquired infections is high, and resources are low. Evidence-based guidelines exist for preventing VAP; however, these guidelines may not be adequately utilized in intensive care units of LMICs.

Aim

This scoping review examined the literature regarding the use of nursing care bundles for VAP prevention in LMICs, to understand the knowledge, practice and compliance of nurses to these guidelines, as well as the barriers preventing the implementation of these guidelines.

Study Design

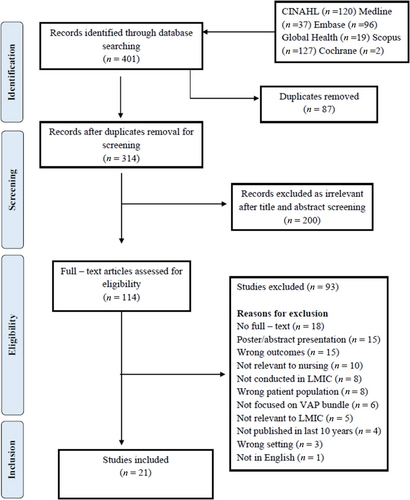

The review was conducted using Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) five-stage framework and the PRISMA-ScR guidelines guided reporting. Searches were performed across six databases: CINAHL, Medline, Embase, Global Health, Scopus and Cochrane, resulting in 401 studies.

Results

After screening all studies against the eligibility criteria, 21 studies were included in the data extraction stage of the review. Across the studies, the knowledge and compliance of nurses regarding VAP prevention were reported as low to moderate. Several factors, ranging from insufficient knowledge to a lack of adequate guidelines for VAP management, served as contributing factors. Multiple barriers prevented nurses from adhering to VAP guidelines effectively, including a lack of audit/surveillance, absence of infection prevention and control (IPC) teams and inadequate training opportunities.

Conclusions

This review highlights the need for adequate quality improvement procedures and more efforts to conduct and translate research into practice in intensive care units in LMIC.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

IPC practices are vital to protect vulnerable patients in intensive care units from developing infections and complications that worsen their prognosis. Critical care nurses should be trained and reinforced to practice effective bundle care to prevent VAP.

What is known about the topic

- The burden of hospital-acquired infections is significantly higher in low-middle-income countries, and the majority of those infections are preventable.

- Critical care nurses provide most of the care and supervision to mechanically ventilated patients; their practices influence patient outcomes.

- Evidence-based care bundles are proven to reduce hospital-acquired infections when implemented together effectively.

What this paper adds

- Nurses' knowledge, practice and compliance with care bundles were found to be low to average in intensive care units in LMICs.

- Non-compliance to care bundles was associated with nurses' lack of knowledge and positive attitude towards prevention guidelines.

- Systemic factors such as inadequate facilities and infrastructure of health care settings, absence of infection prevention and control teams and lack of effective implementation of guidelines contribute to the burden of VAP in low-middle-income countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Despite clinical practice guidelines, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a leading factor for morbidity and mortality among intensive care unit (ICU) patients. VAP is a hospital-acquired infection that develops 48 h or more after mechanical ventilation (MV) via endotracheal intubation.1 VAP weakens the immune system, increasing the risk of multi-organ complications, including sepsis and death.2 Mortality from VAP ranges from 24%–50% to 70% in high-risk patients.3 It prolongs the length of ICU stays and increases health care costs.4 A systematic review by Kharel et al.5 reported that VAP incidence rates varied between countries in Southeast Asia, ranging from 2.13 to 116 per thousand ventilator days. Mehta et al.6 report VAP rates to be three to five times higher in developing countries than in developed countries.6 Patients in the Middle East receiving MV are at higher risk of developing VAP, with twice the risk of mortality than those in the United States.7

Critical care nurses provide direct care to MV patients and play a significant role in preventing the development of VAP. Evidence-based guidelines for VAP prevention exist, and these interventions are grouped into bundles to assist nurses in delivering quality care.8 However, nurses may need adequate understanding and consistent use of these interventions, especially in low-middle-income countries (LMICs). The consistent use of these interventions relies on several factors, including nurses' knowledge of guidelines and effective surveillance by nursing management.9 The gap between knowledge and practice is intensified when there are limited opportunities for the training of nurses, along with the inability of the health care organization to transfer evidence-based research into practice. An informal search of the literature revealed limited evidence and knowledge syntheses on the nursing care practices for VAP prevention in LMICs, as well as the need for more data on the incidence of VAP in some LMICs.10 It indicates a strong need to explore the extent of literature regarding the use of nursing care bundles to prevent VAP in LMICs and to understand the challenges to successfully implementing these care practices. This review is the first summary of evidence on the care practices of nurses regarding VAP prevention in LMICs, and it can provide insight into areas of quality improvement for reducing the occurrence of VAP in LMICs by exploring factors pertaining to nursing practice.

2 AIM

This review aimed to scope research evidence regarding using nursing care bundles to prevent VAP in LMICs. The specific objectives included (a) exploring the literature about the knowledge, practice and compliance of nurses in LMICs regarding nursing care bundles for VAP prevention and (b) identifying the barriers to the implementation and utilization of nursing care bundles in LMICs for VAP prevention.

3 METHODS

This scoping review was conducted using Arksey and O'Malley's11 five-stage framework. We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines to enhance the robustness of reporting.12 The five stages of this review are presented in Appendix A.

3.1 Identification of relevant studies

In consultation with a health sciences librarian, a broad search strategy was developed for application across six databases: CINAHL, Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, Global Health and Cochrane Library. The search strategy comprised of keywords derived from the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework13 (Appendix A). The key terms are defined in Table 1. The searches from the six databases were then exported to Covidence to ensure efficient and reliable screening of the studies throughout the review process.16 A sample search from Medline is attached in Appendix B.

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | VAP is defined as hospital-acquired pneumonia that develops 48 h or more after the onset of mechanical ventilation via endotracheal intubation in the ICU14 |

| Nursing/VAP bundles | VAP Bundles refer to a group of evidence-based nursing interventions useful in preventing VAP when implemented collectively.8 |

| Low-middle income countries | Low-middle-income countries are countries of economies with a gross national income per capita between $1086 and $425515 For a list of LMICs, see the search strategy in Appendices (LMIC filter) |

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LMICs, low-middle-income countries; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

3.2 Eligibility criteria

Clear inclusion–exclusion criteria were developed to screen relevant studies, which are detailed in Table 2. Because of resource and budgetary limitations, grey literature and bibliographical searches were not performed, and only articles published in English were included. Two independent reviewers (A.I.R, A.A.) screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text screening against the eligibility criteria. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion, including a third team member (E.P.).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LMICs, low-middle-income countries; MV, mechanical ventilation; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

3.3 Data selection and charting

After independent reviewing of the full-text articles, a data extraction table was developed using Excel to extract the following information from the included studies: author(s), title of study, year of publication, study location (country), aim, study population, methodology, instrument, intervention type (if any), bundle components under review, outcomes/key findings, barriers to practice/compliance, facilitators to practice/compliance. The second reviewer assisted in the initial stages of the extraction process and validated the extraction. The table is presented in Appendix D.

3.4 Quality appraisal and mitigating bias

Scoping reviews do not require quality appraisals of the studies to be included in the review.17 However, it was essential to assess the quality of the included studies to determine the level of evidence available in the field. Each article was assessed by two reviewers (A.I.R., A.A.) for methodological quality. The rigour of the identified studies was appraised by pertinent Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal tools for quantitative studies (i.e., cross-sectional, quasi-experimental) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist for RCT and qualitative studies according to the design of each study (see Appendix C). The quality of the articles was rated as strong, moderate, or weak based on the number of correct (i.e., yes) responses for each study (i.e., 8–11 = strong, 5–7 = moderate, 1–4 = weak).

To minimize the risk of bias, we employed predefined eligibility criteria, selected studies through anonymous independent votes through the Covidence platform and resolved conflicts through a third reviewer and team discussions. Additionally, we did not exclude any studies based on their methodological rigour. We provided a methodological assessment, employed a detailed pre-defined extraction table and reviewers independently extracted data (A.I.R., A.A.), which were confirmed by a third reviewer (E.P.). Interpretations and conclusions were discussed with the team.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Identification of potential studies

A total of 401 studies were identified across six databases (CINAHL N = 120, Medline N = 37, Embase N = 96, Global Health N = 19, Scopus N = 127, Cochrane N = 2) and were imported to Covidence. Following the removal of 87 duplicates, we screened 314 studies for title and abstract guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After excluding studies identified as irrelevant (n = 200), 114 studies were proceeded to full-text review. We were unable to retrieve full texts for 18 studies, whereas 15 studies were abstract presentations for conferences, which were all then excluded. We excluded another 81 studies for the reasons outlined in the PRISMA flow diagram, resulting in 21 studies for final data extraction.

4.2 Characteristics of the included studies

Of the 21 studies, 90% were from South Asia and the Middle East (i.e., Iran, India, Pakistan, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Yemen and Jordan). In contrast, only two studies were from Africa (i.e., Tanzania and Ethiopia). Most studies were published in the past 5 years (62%). Notably, 14 out of 21 studies used a cross-sectional study design to assess the knowledge and compliance of nurses regarding the VAP bundle2, 8, 18-28 (Mohammed et al., 2020).29 Other study designs included RCT, mixed methods action research, qualitative descriptive study and prospective quasi-experimental time series (Figure 1). The characteristics of individual studies are detailed in Appendix D.

4.3 Quality appraisal

Out of the 21 studies, five were rated high quality, nine were of moderate quality and six were of low quality (See Appendix C). The studies with strong methodological quality had transparent and elaborative recruitment and data collection processes with high-quality analytical statistics/tests reporting. Many moderate/low-quality quantitative did not adequately report sample size/power calculation, sampling frame, sampling techniques, bias and analytical test details. Many observational studies did not comment on the researcher's influence in the observed setting or ways to mitigate associated discrepancies. Although most of the studies were of low quality, they contributed valuable information regarding nurses' knowledge and compliance with VAP guidelines.

4.4 Knowledge, practice and compliance of nurses regarding VAP bundles

4.4.1 Types of VAP prevention strategies

We identified that 10 out of 21 studies used the term ‘VAP Bundles’ to refer to a group of evidence-based nursing interventions helpful in preventing VAP when implemented collectively8, 19, 20, 23, 30-34 (Mohammed et al., 2020). Other studies refer to these interventions/strategies as ‘VAP prevention guidelines’ recommended and published by the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), American Thoracic Society, or Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). The nursing VAP bundle can be viewed as a sub-component of the broader VAP prevention guidelines, which are more diverse and multi-professional. Except for two studies that only evaluated the oral care practices as part of the VAP bundle,22, 25 all of the included studies addressed the following interventions, that were either assessed or implemented as part of the VAP bundle/guidelines: (1) Oral care using chlorhexidine/antiseptic solution, (2) Daily assessment of readiness to wean, (3) Hand washing before and after suctioning; and patient contact, (4) Sterile gloves/procedure for suctioning, (5) Maintaining adequate endotracheal tube (ETT) cuff pressure (20–30 cm of water), (6) Head of bed (HOB) elevation to 30–45°; Semi-recumbent positioning, (7) Sedation vacation, (8) Subglottic suctioning, and (9) Ventilator circuit changes.

4.4.2 Knowledge, practice and compliance of nurses

A total of six studies assessed nurses' knowledge regarding evidence-based guidelines (care bundles) to prevent VAP; seven studies evaluated the compliance/adherence of nurses to the VAP bundle guidelines, whereas five studies assessed both the knowledge and practice of nurses towards the VAP bundle. We identified two studies that solely evaluated the challenges and barriers to successfully implementing VAP prevention guidelines, whereas all studies reported some barriers to VAP education/prevention.

4.5 Knowledge

All the 11 studies that evaluated nurses' knowledge of VAP prevention used self-reported questionnaires or survey tools. In a study by Getahun et al.21 in Ethiopia, 48% of nurses had ‘good’ knowledge, whereas 51.9% had ‘poor’ knowledge about VAP prevention. The poor knowledge score of nurses was consistent with other studies in Pakistan, India and Iraq, where nurses were not aware of the VAP bundle protocol and its correct measures19, 23, 27 (Mohammed et al., 2020). In comparison with other health care providers, Alkubati et al.2 found that in Yemen, the total mean score of nurses' knowledge (37.1%) was significantly lower than that of physicians and anaesthesia technicians (45.6%, 52.2%). Although this finding was different for nurses across studies, Colombage and Goonewardena20 found that nurses in Sri Lanka had overall good knowledge (51%) regarding endotracheal (ET) tube care, where the majority of the nurses practised the VAP bundle in their care setting; however, only 18% reported practising frequent oral hygiene. It was observed in several other studies in Jordan, Sri Lanka, India and Iran that the provision of oral care was not the highest priority of nurses despite understanding and verbalizing its significance for VAP prevention.18, 20, 24, 25, 27, 31

Nurses' knowledge of items of the care bundle varied among studies, pointing to the differences between health care systems in LMICs. In some studies, nurses in Tanzania, India and Iran were reported to have good knowledge of patient positioning, oral care and HOB elevation8, 23, 28 and demonstrated poor knowledge regarding the maintenance of ETT cuff pressure, frequency of circuit changes and use of suction systems8, 23 (Mohammed et al., 2020). Having adequate knowledge of every item of the care bundle does not necessarily warrant best practice but is found to influence the implementation of evidence-based guidelines.28 Among other factors influencing the knowledge of nurses, Sreenivasan et al.25 reported in India that there was no positive correlation between nurses' years of experience and their knowledge, whereas Aloush et al.18 found in Jordan that the level of education, years of experience and previous VAP education all influenced knowledge and practice in some ways.

4.6 Compliance

Nurses' compliance and adherence to VAP bundles were assessed through self-rated checklists or direct observations. Many studies from Jordan, Pakistan, Tanzania, India and Iran reported nurses' compliance with VAP bundle as ‘poor’ to ‘moderate’.8, 18, 19, 26, 31, 32, 34, 35 Aloush et al.18 found that 53% of nurses in Jordan demonstrated unsafe compliance, 29% acceptable, whereas only 18% demonstrated high compliance to VAP bundles. They further state that 46% of nurses reported never using chlorhexidine to provide oral care, and 32% never assessed patients for weaning. Assessing the impact of VAP education on nurses' compliance, Dakshinamoorthy and Chidambaranathan31 found significant differences in compliance with the VAP bundle after implementing a sensitizing program in India emphasizing the impact of education and training on enhancing nurses' knowledge and improving their skills and practice.

Nurses' level of compliance with individual bundle items varied across studies. The differences in nurses' compliance towards the items of the bundle were attributed to several reasons, one of which was the infrastructure of the health care setting (ICU unit). Aloush34 found a significant difference in nurses' compliance with the number of beds per unit and nurse-to-patient ratio in Jordan. Moreover, nurses in the LMIC setting were found to need to be more empowered to perform interventions independently as in developed countries. Most interventions require physician's orders or supervision, and performing such interventions without supervision is not considered ideal in these contexts. For example, regarding assessing patients' readiness for weaning, Tabaeian et al.26 found that in 11 ICUs of four tertiary care hospitals in Iran, compliance with this particular intervention was 0%, as anaesthesiologists primarily managed all weaning-related interventions. Thus, nurses were not involved in implementing these interventions and had no means to practice them.

Many studies used a self-reported checklist for nurses to rate their compliance/adherence to VAP guidelines. There may be better approaches because of the risk of bias. Shamshiri et al.24 highlighted the issue in their study that recorded inconsistencies between self-reported and actual adherence rates in Iran. For instance, 66.3% of respondents reported performing regular antiseptic oral care for all MV patients; however, only four (9.4%) observed episodes documented that oral care was performed.

4.7 Barriers and facilitators to practice

It is essential to understand the barriers and facilitators to VAP prevention as it can give insights into the low knowledge, practice and compliance rate of nurses in LMICs and the gaps between the translation of research into practice. The identified barriers are divided into two sub-categories for better comprehension: personal/internal and external/systemic. Personal/internal barriers refer to the barriers nurses encounter because of their knowledge, attitude, or behaviour. In contrast, external/systemic barriers refer to the barriers that are not under the direct control of nurses and are imposed on them through organizational or administrative factors. Table 3 highlights the main barriers identified across studies.

| Barriers | Type of barriers | Studies reporting barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Internal/personal barriers | Lack of knowledge and skills | Aloush et al.,18 Jordan Atashi et al.,29 Iran Aziz et al.,19 Pakistan Bankanie et al.,8 Tanzania Getahun et al.,21 Ethiopia Javadinia et al.,22 Iran Tabaeian et al.,26 Iran Yazdannik et al.,27 Iran Yeganeh et al.,28 Iran |

| Lack of motivation and accountability | Alkubati et al.,2 Yemen Atashi et al.,30 Iran Bankanie et al.,8 Tanzania Toulabi et al.,36 Iran |

|

| Nurses' unfavourable professional attitudes and beliefs (ignorance) | Atashi et al.,29 Iran Bankanie et al.,8 Tanzania Dakshinamoorthy and Chidambaranathan,31 India Hamishehkar et al.,32 Iran Toulabi et al.,36 Iran |

|

| External/system barriers | Lack of in-service education and training programs for nurses | Alkubati et al.,2 Yemen Atashi et al.,30 Iran Colombage and Goonewardena,20 Sri Lanka Getahun et al.,21 Ethiopia Toulabi et al.,36 Iran |

| Absence or lack of consistent policy, guidelines, or protocols for VAP bundles/prevention | Alkubati et al.,2 Yemen Bankanie et al.,8 Tanzania Hamishehkar et al.,32 Iran Shamshiri et al.,24 Iran Sreenivasan et al.,25 India |

|

| Ineffective supervision/surveillance of guidelines; lack of audit and feedback; absence of infection control teams | Alkubati et al.,2 Yemen Atashi et al.,30 Iran Kalyan et al.,23 India Shamshiri et al.,24 Iran Toulabi et al.,36 Iran |

|

| Insufficient staffing; increased workload; low nurse-to-patient ratio | Atashi et al.,30 Iran Aziz et al.,19 Pakistan Bankanie et al.,8 Tanzania Javadinia et al.,22 Iran Shamshiri et al.,24 Iran Sreenivasan et al.,25 India Tabaeian et al.,26 Iran Toulabi et al.,36 Iran Yeganeh et al.,28 Iran |

|

| Inadequate equipment/supplies/resources (according to recommended guidelines) | Alkubati et al.,2 Yemen Aloush et al.,18 Jordan Atashi et al.,30 Iran Javadinia et al.,22 Iran Sreenivasan et al.,25 India Toulabi et al.,36 Iran Yazdannik et al.,27 Iran Yeganeh et al.,28 Iran |

Nurses and management work side by side and have supplementary roles in the success of any program. Many barriers stemmed from the attitudes and behaviours of nurses towards their work. Hamishehkar et al.32 reported that nurses needed to understand the importance and criticality of performing such interventions compared with other tasks, such as completing documentation. Toulabi et al.36 further elaborated on this issue, indicating management's disproportionate attention to evaluating documentation practices rather than care practices in Iran, highlighting the fact that effective leadership and management were important in the execution of such programs (i.e., systemic barriers). Lack of adequate support and guidance, along with ineffective surveillance/supervision, reduces nurses' sensitivity towards these interventions and, in turn, their adherence to guidelines.8, 24, 30, 32 In addition, not all of the recommended international guidelines are feasible to implement in LMICs, where resources are limited and equipment is not advanced.2, 30 Throughout many studies, nurses with a higher level of education proved to be more knowledgeable and compliant with VAP guidelines. Similarly, the education of nurses regarding VAP prevention and frequent training improved knowledge and compliance.18, 21, 23

5 DISCUSSION

This scoping review provides a detailed account of what is known in the literature about the use of nursing care bundles for VAP prevention in LMICs, reporting nurses' knowledge, compliance and barriers to effectively implementing these care bundles. We found that despite the understanding of the importance of VAP guidelines, there is a significant gap in the implementation of these guidelines, which has been implicated in poor adherence to VAP guidelines and, in turn, higher VAP rates in LMICs.19, 33 Although the body of literature from the medical perspective is diverse, nursing literature still needs to catch up in quantity and quality. Moreover, research findings are poorly integrated into practice in LMICs,18 leading to knowledge differences and inadequate outcomes. This poor integration may stem from ineffective health care leadership and the challenges of sharing knowledge or conducting high-quality training in resource-limited countries.8, 30

A common strategy found to disseminate evidence-based interventions and improve the knowledge and compliance of nurses was education and training programs. Such programs helped improve knowledge regarding VAP guidelines.31, 33, 36 A study by Mutaru et al.37 in Ghana reported high knowledge and compliance rates of nurses towards infection prevention and control guidelines, attributed to the education and training curriculum offered to nurses. They further emphasized that the higher compliance rate of nurses was also because of their positive attitude towards adherence to infection control guidelines. However, more than education was needed to guarantee nurses' compliance with guidelines and the sustainability of quality improvement processes. Aloush35 reported that although VAP educational interventions improved nurses' knowledge and compliance, other factors like heavy workload also impacted nurses' compliance. Organizations must prioritize VAP prevention and develop relevant strategies addressing education, monitoring and establishing quality improvement processes.38

It should be noted that an essential determinant in the adoption and success of such programs is the attitude and behaviour of nurses towards these care bundles in daily practice. One of the challenges in implementing VAP prevention guidelines was linked to modifying nurses' behaviour, including environmental, social and contextual aspects.38 Active managerial efforts are required to provide nurses with resources and optimal working conditions and develop strict surveillance measures.24, 30, 36 Despite the importance of infection control and surveillance teams in VAP prevention, many health care organizations in LMICs still need primary infection control and surveillance programs and data regarding the incidence of VAP.2, 38

An integral element behind the success of institutional approaches is the involvement of nurses, as they are the drivers of patient care in the health care system. It was found that nurses were not adequately involved in the decision-making or policy development processes.27 When nurses are not an equal part of such quality improvement processes, they do not tend to understand the reasoning behind introducing such initiatives, leading to ignorance and lack of interest. The lack of nurses' involvement in decision-making is also rooted in the traditional perception and poor image of nurses as physician's subordinates in LMICs. These power dynamics lead to weak interdisciplinary relationships and a lack of communication, essential for a healthy work environment and the success of such protocols.39 Leadership and management must empower nurses to make them self-aware of their potential and value their contributions towards quality improvement.26

A significant finding across studies was the lack of transferability of VAP prevention guidelines from high income to LMIC contexts.30 Health care facilities in LMICs are not consistently resourced as per advanced international standards (e.g., kinetic beds and closed suction systems). Moreover, the present resources may need to be maintained adequately to ensure functionality.27, 28, 36 Among such resource constraints, it becomes difficult for nurses and management to prioritize care processes for treatment over prevention. This issue was overt during the COVID-19 pandemic when nurses did not have enough PPE (personal protective equipment) to protect themselves, let alone prevent their patients from VAP. This leads to the question of what is being done by global health authorities to make VAP guidelines more applicable to LMICs. Future research needs to focus on making VAP guidelines more cost-effective and appropriate to LMICs' context. Additionally, researchers from LMICs may contribute to improving the quality of literature relevant to LMICs, especially nursing.

6 LIMITATIONS

This scoping review was the first to evaluate the breadth of literature regarding nursing VAP bundles in LMICs. It provides a systematic and transparent approach to searching the literature, which other reviewers can replicate. Because of limited resources and funding, searching for additional literature sources (i.e., grey literature, theses) was not conducted. Also, studies published in a language other than English were excluded, as there were limited resources for translation. Because of the evolving context of health care in LMICs, we wished to capture current evidence that can inform practice in contemporary clinical setting and therefore we limited the inclusion of studies within the past 10 years. Studies focused on nurses or patients in paediatric/neonatal ICUs were excluded to narrow the inclusion criteria and maintain the uniformity of nursing interventions. Additionally, our search strategy focused specifically on VAP, and not other ventilator-associated events, like atelectasis, or ventilation deterioration, and we may have therefore missed evidence addressing VAP in the broader context of ventilator-associated events. Reliance on self-reporting of compliance in several of the identified studies may have caused over- or under-estimation of actual compliance. Furthermore, the quality appraisal process revealed varying quality of studies which has the potential to impact the overall strength of our conclusions.

7 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This review examined the breadth of literature surrounding the use of nursing care bundles for preventing VAP in LMICs. The available evidence provided insights into the knowledge, practice and compliance of nurses in LMICs while highlighting barriers. Although nurses' knowledge and compliance were found to be average across many studies, several other factors are responsible for ensuring the implementation of best practices, including work environment and adequate resources. The evidence raises the question of the feasibility of the VAP bundles in several low-resource settings, and they highlight the role of appropriate support and prioritization from management. The importance of appropriate training of nurses' use of consistent policies and protocols and effective surveillance cannot be emphasized enough, as they emerged as the most common barriers. To control and reduce the incidence of VAP, leadership and management must devise plans involving nurses in quality improvement processes through education and research. Nursing researchers and educators in LMICs must step up to conduct high-quality research to report nursing care practices for VAP prevention and identify cost-effective strategies to improve the knowledge and practice of nurses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AIR, EP and CM conceptualized the review and developed the initial protocol and review process. AIR and AA conducted title and abstract and full-text screening. AIR, AA and EP contributed to the extraction process. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

APPENDIX A

Arksey and O'Malley's five-stage framework

- Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question:

- Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies:

- Stage 3: Study Selection:

- Stage 4: Charting the Data:

- Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results:

The results section provides the summary and findings from the data analysed throughout the review.

APPENDIX B

Sample MEDLINE search

| Searches | Results |

|---|---|

| (1) egypt/ or morocco/ or tunisia/ or cameroon/ or central african republic/ or chad/ or congo/ or ‘democratic republic of the congo’/ or equatorial guinea/ or gabon/ or ‘sao tome and principe’/ or burundi/ or djibouti/ or eritrea/ or ethiopia/ or kenya/ or rwanda/ or somalia/ or south sudan/ or sudan/ or tanzania/ or uganda/ or angola/ or lesotho/ or malawi/ or mozambique/ or swaziland/ or zambia/ or zimbabwe/ or benin/ or burkina faso/ or cabo verde/ or cote d'ivoire/ or gambia/ or ghana/ or guinea/ or guinea-bissau/ or liberia/ or mali/ or mauritania/ or niger/ or nigeria/ or senegal/ or sierra leone/ or togo/ or honduras/ or nicaragua/ or bolivia/ or kazakhstan/ or kyrgyzstan/ or tajikistan/ or uzbekistan/ or cambodia/ or laos/ or myanmar/ or philippines/ or timor-leste/ or vietnam/ or bangladesh/ or bhutan/ or india/ or afghanistan/ or syria/ or yemen/ or nepal/ or pakistan/ or sri lanka/ or ‘democratic people's republic of korea’/ or mongolia/ or borneo/ or melanesia/ or papua new guinea/ or vanuatu/ or haiti/ or comoros/ or madagascar/ or sri lanka/ or (Afghanistan or Afghani or Afghan or Angola* or Bangladesh* or Benin or Beninese or Bhutan or Bolivia* or Burkina Faso or Burkinabe or Burundi* or Cabo Verde or Cape Verde or Cambodia* or Cameroon* or ‘Central African Republic’ or Chad or Chadian or Tchad or Comoros or Comoran or Congo or Congolese or ‘Cote d'ivoire’ or Ivorian or Djibouti or Egypt or Egyptian or ‘El Salvador’ or Salvadoran or Eritrea* or Ethiopia* or Gambia or Gambian or (Georgia not United States) or Ghana* or Guinea or ‘Guinea Bissau*’ or Haiti or Haitian or Hondura* or India or (Indian not American) or Indonesia* or Kazakhstan or Kenya* or Kiribati or North Korea* or DPRK or Kosovo or Kosovar or Kosovan or Kyrgyz* or Laos or Laotian or Lesotho or Mosotho or Basotho or Liberia* or Madagascar or Malagasy or Malawi* or Mali or Malian or Mauritania* or Micronesia* or Moldova* or Mongolia* or Morocco or Moroccan or Mozambique or Mozambican or Myanmar or Burmese or Myanmarese or Nepal or Nepalese or Nicaragua* or Niger or Nigerien or Nigeria or Pakistan* or ‘Papua New Guinea*’ or Philippines or Filipino* or Rwanda* or ‘Sao Tome and Principe’ or ‘San Tomean’ or Senegal* or ‘Sierra Leone*’ or ‘Solomon Island*’ or Somalia* or Sri Lanka* or Sudan or Sudanese or Swaziland or Swazi or Syria or Syrian or Tajikistan or Tajik or Tadzhik or Tanzania* or ‘Timor Leste’ or Timorese or Togo or Togolese or Tunisia* or Uganda* or Ukraine or Ukrainian or Uzbekistan* or Uzbeki or Vanuatu or Vietnam* or ‘West Bank’ or Gaza or Yemen* or Zambia* or Zimbabwe*).ti,ab,cp. | 1 309 896 |

| (2) (‘low* middle* countr*’ or LMIC or LMICs).mp. | 9103 |

| (3) 1 or 2 | 1 315 563 |

| (4) nurs*.mp. | 793 849 |

| (5) 3 and 4 | 23 096 |

| (6) (‘Ventilat* acquired pneumonia’ or ‘ventilat* associated pneumonia’ or VAP or ‘intubat* pneumonia’).mp. | 8836 |

| (7) 5 and 6 | 37 |

APPENDIX C

Quality appraisal

| Author and year | Quality appraisal tool | Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Alkubati et al. (2021)2 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Low |

| Aloush et al. (2018)18 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Strong |

| Aloush (2017)34 | CASP RCT checklist | Low |

| Atashi et al. (2018)29 | CASP qualitative checklist | Strong |

| Aziz et al. (2020)19 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Bankanie et al. (2021)8 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Strong |

| Colombage and Goonewardena (2020)20 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Low |

| Dakshinamoorthy and Chidambaranathan (2018)30 | JBI critical appraisal tool for quasi-experimental studies | Low |

| Getahun et al. (2022)21 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Hamishehkar et al. (2014)31 | JBI critical appraisal tool for analytical cross-sectional studies | Moderate |

| Javadinia et al. (2014)22 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Kalyan et al. (2020)23 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Mohammed et al. (2020) | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Strong |

| Samra et al. (2017)32 | JBI critical appraisal tool for quasi-experimental studies | Moderate |

| Shahnaz et al. (2018)33 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Low |

| Shamshiri et al. (2016)24 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Sreenivasan et al. (2018)25 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Strong |

| Tabaeian et al. (2017)26 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Low |

| Yazdannik et al. (2018)27 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

| Yeganeh et al. (2019)28 | JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies | Moderate |

- Abbreviations: CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Program; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute.

APPENDIX D

Summary of included studies

| Author, year and country | Aim/purpose | Study population | Methodology | Instrument | Intervention type (if any) | Bundle components under review/consideration | Outcomes/Key findings | Barriers to practice/compliance | Facilitators to practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkubati et al. (2021),2 Yemen | Evaluate the knowledge level of HCWs in ICUs regarding the evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of VAP and to assess their knowledge in relation their socio-demographic characteristics. | Health care workers in ICU providing care to MV patients: physicians (20), anaesthesia technicians (20) and nurses (80) | Descriptive cross-sectional design | Self-administered multiple-choice questionnaire:

|

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Aloush et al. (2018),18 Jordan | Evaluated nurses' and hospitals' compliance with VAP prevention guidelines, factors affecting level of compliance and barriers to compliance | Nurses working in ICUs (N = 471) | Cross-sectional self-reported survey | Questionnaire consisted of four parts:

|

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Aloush (2017),34 Jordan | Evaluating nurses' compliance with VAP-prevention guidelines following an educational program and the factors that influence their compliance | Nurses working in ICUSs of five hospitals in Jordan (N = 120) | Randomized clinical trial (2-group post-test only design) A non-participatory observational approach was used to assess participants. |

A 9-item structured observation sheet:

|

Experimental group—received an intensive VAP education course consisting of 4 sessions (2 h per session) |

|

|

|

|

| Atashi et al. (2018),29 Iran | Explore Iranian critical care nurses' perspectives on the barriers to VAP prevention in ICUs | Critical care nurses in ICUs (N = 23) | Qualitative descriptive study | Face to face semi-structured interviews and field observation | N/A |

|

The findings from the interviews were categorized in three main categories (barriers) and 10 sub-categories:

|

|

|

| Bankanie et al. (2021),8 Tanzania | To explore ICU nurses' knowledge, compliance and barriers towards evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of VAP in Tanzania | ICU nurses from all major hospitals in Tanzania (N = 116) | Cross-sectional study with quantitative approach | Self-reported compliance questionnaire | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Colombage and Goonewardena (2020)20 | To assess nurses' knowledge and practices on caring for patients with endotracheal tube in intensive care units of national hospital of Sri Lanka | Critical care nurses (N = 334) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Self-administered questionnaire (five sections):

|

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Dakshinamoorthy and Chidambaranathan (2018),30 India | The aim of this study was to determine the compliance of the bundle and if <95% devise strategies to improve compliance. To assess the compliance rate of VAP bundle and effectiveness of sensitizing program by comparing the compliance rate of VAP before and after the program |

Nurses working in the critical care unit | Prospective quasi-experimental time series study | Observational checklist | Sensitizing program on updated and revised VAP bundle |

|

|

|

|

| Getahun et al. (2022),21 Ethiopia | To assess the knowledge of VAP prevention among critical care nurses. | Nurses working in the ICUs (N = 213) | Multi-center institutional-based cross-sectional study | Structured self-administered questionnaire:

|

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Hamishehkar et al. (2014),31 Iran | To determine the compliance rate of the VAP care bundle and evaluate the effect of nurses' education on it. | Nurses and patients in the ICUs | Observational study Phase 1: Observation Phase 2: Education Phase 3: Evaluation of compliance after one month |

Observational checklist | Educational pamphlets containing VAP bundle care compliance results and guidelines to each nurse. | Evaluated knowledge regarding the correct

|

|

|

|

| Javadinia et al. (2013),22 Iran | To assess the opinions and performance status of nurses working in ICUs of Birjand hospitals concerning rendering oral care to patients under mechanical ventilation. | Nurses working in the ICU (N = 53) | Cross-sectional study | Questionnaire:

|

N/A | Oral care (Frequency, procedures, type of tools/solution, obstacles) |

|

|

|

| Kalyan et al. (2020),23 India | To assess the knowledge and practices of intensive care nurses on prevention of VAP and to assess the association between knowledge and practice | ICU nurses (n = 108) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Knowledge based questionnaire and observation checklist | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Aziz et al. (2020),19 Pakistan | To assess ICU nurses' knowledge and practices of VCB in Lahore Pakistan. | Critical care nurses (n = 136) | Survey based cross-sectional descriptive study | Knowledge based questionnaire Checklist to assess nurses practices of VCB |

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Mohammed et al. (2020), Iraq | To assess nurses' knowledge regarding VAP prevention and expected nursing practice for VAP prevention | Nurses (n = 126) | Descriptive cross-sectional survey | Questionnaire:

|

N/A |

|

|

||

| Samra et al. (2017),32 Egypt | The evaluation of adherence to VAP bundle and its effect on VAP rates and mortality, while the secondary outcome was the cost saving resulting from implementation of VAP bundle. | MV patients (divided into prospective and retrospective groups) | Comparative interventional design | Surveillance reports | Prospective group underwent VAP bundle items application, measurement of VAP bundle compliance daily and ranking monthly along with laboratory and diagnostic evaluations |

|

|

|

|

| Shahnaz et al. (2018),33 India | To assess and compare the level of competency among ICU nurses in the use of VAP bundle of selected government and private hospitals. To determine the relationship between the levels of competency of ICU nurses in the use of VAP bundle of both hospitals. |

ICU nurses (30 government, 30 private hospital) | Quantitative (Non experimental) research approach, comparative descriptive research design | Structured questionnaire and structured observational checklist | N/A |

|

|

||

| Shamshiri et al. (2016),24 Iran | To determine the rate of adherence to evidence-based post-insertion recommended care practices after admission into the intensive care unit for CVC, IUC and MV | ICU nurses (n = 96) 85 post-insertion MV care episodes |

Structured observational cross-sectional design | Checklist and self-reported questionnaire | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Sreenivasan et al. (2018),25 India | To assess the knowledge, attitudes and practices of ICU nurses on oral care in critically ill patients | ICU nurses (n = 200) | Cross-sectional survey | Questionnaire | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Tabaeian et al. (2017),26 Iran | To evaluate the compliance with the standards for prevention of VAP by nurses in the intensive care units. | Nurses (n = 120) in 11 ICUs | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Observational checklist | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Toulabi et al. (2020),35 Iran | To identify the problems and challenges of quality improvement in VAP management, to develop and implement problem solving strategies and to ultimately evaluate the effects of these strategies on the performance of medical personnel in ICUs | n = 18 (12 ICU nurses, head nurse, infection control nurse, educational supervisor, 3 clinical supervisors) | Action research (Quantitative phase—540 performance cases observation) (Qualitative phase—semi structured interviews, FGD, notes regarding challenges of quality improvement of VAP) |

Quantitative—observation checklist Qualitative—open-ended questionnaire |

Action plans: Supplying human resources, organizing training workshops, improving the equipment and upgrading the physical structure |

|

|

|

|

| Yazdannik et al. (2018),27 Iran | To assess performance of ICU nurses in providing respiratory care | ICU nurses (n = 120) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Questionnaire and performance observation checklist | N/A |

|

|

|

|

| Yeganeh et al. (2019),28 Iran | To assess the intensive care unit nurses' knowledge of evidence-based guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) prevention including barriers that affect nurses' knowledge to the implementation of these guidelines | ICU nurses (n = 219) | Cross-sectional study | Multiple-choice questionnaire:

|

N/A |

|

|

|

- Abbreviations: ET, endotracheal; ETT, endotracheal tube; HOB, head of bed; ICU, intensive care unit; LMICs, low-middle-income countries; MV, mechanical ventilation; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; VCB, ventilator care bundle, CVC, Central Venous Catheter; DVT, Deep Vein Thrombosis; EBG, Evidence Based Guidelines; FGD, Focus Group Discussion; HAI, Healthcare Associated Infections; HCW, Healthcare Workers; IUC, Indwelling Urinary Catheter.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.