Nursing workload assessment in an intensive care unit: A retrospective observational study using the Nursing Activities Score

Abstract

Background

Nursing Activities Score (NAS) is a promising tool for calculating the nursing workload in intensive care units (ICU). However, data on intensive care nursing activities in Portugal are practically non-existent.

Aim

To assess the nursing workload in a Portuguese ICU using the NAS.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort study developed throughout the analysis of the electronic health record database from 56 adult patients admitted to a six-bed Portuguese ICU between 1 June–31 August 2020. The nursing workload was assessed by the Portuguese version of the NAS. The study was approved by the Hospital Council Board and Ethics Committee. The study report followed the STROBE guidelines.

Results

The average occupancy rate was 73.55% (±16.60%). The average nursing workload per participant was 67.52 (±10.91) points. There was a correlation between the occupancy rate and the nursing workload. In 35.78% of the days, the nursing workload was higher than the available human resources, overloading nurse staffing/team.

Conclusions

The nursing workload reported follows the trend of the international studies and the results reinforce the importance of adjusting the nursing staffing to the complexity of nursing care in this ICU. This study highlighted periods of nursing workload that could compromise patient safety.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

This was one of the first studies carried out with the NAS after its cross-cultural adaptation and validation for the Portuguese population. The nursing workload at the patient level was higher in the first 24 h of ICU stays. Because of the ‘administrative and management activities’ related to the ‘patient discharge procedures’, the last 24 h of ICU stays also presented high levels of nursing workload. The implementation of a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:1 may contribute to safer nurse staffing and to improve patient safety in this Tertiary (level 3) ICU.

What is known about the topic

- The Nursing Activities Score (NAS) assesses 80.8% of the nursing workload in intensive care units (ICUs) compared with Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System 28 that only assesses 43.3% of therapeutic interventions.

- The (Portuguese version of) NAS is a promising tool that could be used in Intensive and/or intermediate care units to assess the nursing workload at patient level and/or at ICU level during a given period.

What this paper adds

- The nursing workload at the patient level was higher in the first 24 h of ICU stays and ‘consumes’ an average of 19.36 (±2.61) h of nursing care.

- The last 24 h of ICU stays also presented high levels of nursing workload, includes ‘administrative and management activities’ related to the ‘patient discharge procedures’ and ‘consumes’ an average of 18.74 (±2.43) h of nursing care.

- According to our results, the implementation of the recommendations/ratios proposed by ‘Ordem dos Enfermeiros’ (National Nursing Council) may contribute to safer nurse staffing and to improve patient safety in this Tertiary (level 3) ICU.

1 INTRODUCTION

The number of patients requiring admission into intensive care units (ICUs) is increasing worldwide.1, 2 Nursing activities in ICUs are dynamic and variable over the 24-h period3 and the management of nursing workload is becoming a challenge.1, 4-9 In fact, increased nursing workload is associated with increased incidence of adverse events10, 11 that could compromise the patient safety culture12-14 and the quality of care.6, 15, 16

According to a recent Systematic Review,4 Health care Systems should invest in appropriate nurse staffing models to enhance patient health.

Furthermore, a 5-year retrospective study conducted in a Portuguese ICU concluded that the systematic nursing workload assessment in critical care contexts could be an important strategy to manage the nursing team (and the nursing care process) and suggested the implementation of the Nursing Activities Score (NAS).5

2 BACKGROUND

According to the World Health Organization,17 ‘Patient Safety’ includes the efforts made in order to minimize preventable harm to patients during their interaction with the healthcare services. Therefore, patient safety decisions and healthcare policies must consider the entire care context, including the current knowledge about patients' characteristics and available (human and technological) resources.

Thus, the assessment of care needs and nursing workload assumes a prominent role when we intend to reconcile care quality, resource optimization, and costs reduction.18 Based on that, ‘Ordem dos Enfermeiros’ (National Nursing Council) consider that nurse staffing, their skills, and level of qualification are key elements to achieve safety and quality of care19 and we should use criteria and methodologies to adapt human resources to the real needs of our population.

So, it is essential to identify objective indicators that measure the real needs of patients and nursing professionals, namely in ICUs.

Analysing the international literature, we found that most of the studies that assess the nursing workload in ICUs are based on the Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System 28 (TISS 28),20 on the Nine Equivalents of Nursing Manpower Use Score (NEMS)21 and/or on the NAS.22

The TISS 28 represents one of the best-known nursing workload assessment tools. It was validated in a multicentric way and has been used in ICUs all around the world.20

The NEMS represents a reduced and simplified version of TISS 28. It only considers nine items to assess the nursing workload in ICUs.21 However, it had low applicability in Portugal.23

The NAS includes a set of activities that describe the nursing workload in ICUs of different typologies. It assigns different weights to several nursing activities and the final score describes more reliably the time spent in the provision of nursing care.22

According to Miranda et al.,22 the NAS assesses 80.8% of the nursing workload in ICUs compared with TISS 28 that only assesses 43.3% of therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, the NAS allows to assess the nursing workload based on the time spent on nursing activities and it is independent of the illness severity.22-24

Therefore, the NAS is a promising tool for calculating the nursing workload in different intensive and/or intermediate care units because it is based on the specific activities of the nursing teams. The NAS assesses the provision of direct care to the patient and their families, such as hygiene procedures, mobilization and positioning, support, and care for patients and family members. It also includes the provision of indirect care in administrative and management terms. It is not dependent on the illness severity, because its construction and validation were based on autonomous and interdependent nursing activities.23, 25

In recent years, several international studies have been carried out with NAS in intensive and intermediate care units of different levels and typologies.26-32 However, data in Portugal are practically non-existent.

3 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF STUDY

The main objective of this study was to assess the nursing workload in an ICU using the Portuguese version of the NAS for 3 months.

- To analyse the nursing workload generated by each participant during the length of ICU stays.

- To analyse the nursing workload generated by each participant in the first 24 h of ICU stays.

- To analyse the nursing workload generated by each participant in the last 24 h of ICU stays.

- To analyse the variation of nursing workload in the ICU for every 24 h throughout the study period.

4 DESIGN AND METHODS

4.1 Study type and design

Observational, analytical, and retrospective cohort study with the analysis of the electronic health record database. The study was developed in a six-bed ICU in the Central Region of Portugal. The ICU belongs to the Portuguese National Health System and is classified as a Tertiary (level 3) ICU. During the period under analysis, the ICU had a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:2, 24 h a day, 365 days a year.

The period under analysis was between 1 June–31 August 2020.

This study was executed and reported following Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies33 (Supplementary File 1) and took into account the data documented in patients' electronic health records.

4.2 Sample/participants

- Patients admitted in the ICU in the period under analysis.

- Patients with ≥18 years old at the time of admission.

- Patients with a length of ICU stay of fewer than 24 h.

Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above, we obtained a total sample of 56 patients in critical condition.

4.3 Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Hospital Council Board and Ethics Committee in July 2020 (Document/Meeting Reference Number: 131 of 23 July 2020) and the data were collected by the principal investigator during September 2020. Confidentiality of the data and anonymity of the participants in the study were always guaranteed. Each patient was coded numerically in chronological order, making it possible to guarantee and maintain the anonymity of the participants throughout the study.

4.4 Data collection

All assessment variables for each patient included in the study were extracted from the electronic health record database.

The sociodemographic variables under analysis were ‘gender’ and ‘age’. The ‘gender’ of each participant was dichotomized into ‘male’ and ‘female’. The ‘age’ was assessed in years considering each participant's date of birth.

The clinical and ICU variables were the ‘type of admission’, ‘reason for hospitalization’, ‘diagnoses’, ‘outcome’, ‘length of stay’, and ‘occupancy rate’. The ‘type of admission’ of each participant was categorized as ‘emergency service’; ‘operating room’; ‘internal transfer’; and ‘external transfer’. The participants presented different (multi)organic problems, thus the ‘reason for hospitalization’ was dichotomized into ‘medical problems’ and ‘surgical problems’. The ‘diagnoses’ were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The participants' ‘outcome’ was categorized as ‘internal transfer’; ‘external transfer’; or ‘death’. The ‘occupancy rate’ was calculated according to the formula ‘Occupancy rate = [(number of hospitalized participants/ICU capacity) × 100]’. The ‘length of stay’ was counted in days. The ‘point zero’ was the time of admission. The ‘endpoint’ was the time of discharge.

Finally, the ‘nursing workload’ was assessed according to the Portuguese version of the NAS.23, 25

4.5 Validity and reliability/rigour

The original version of NAS22 was validated in a study developed in 99 ICU in 15 countries and the results indicated that it explains 80.8% of the nursing time (vs. 43.3% in TISS-28).15, 22, 23, 34

The NAS includes seven major categories and 23 items. Each item has a specific score based on the real-time assessment of nursing activities length. The sum of the 23 items ranges between 0 and 177%. The total score attributed to each participant results from the sum of the scores of the different items and corresponds to the participants' direct and indirect care needs. The final score represents the amount of time each participant spent (in terms of nursing care) in the last 24 h. Therefore, a total score of 100.0% indicates the work of one nurse over a 24-h period.15, 22, 23, 25, 34

The concurrent validity of the Portuguese version of the NAS was demonstrated by the statistically significant correlation between NAS and TISS 28 (r = .678; p = .000), as well as the result of multiple linear regression (r2 = .303, p = .000). The convergent validity was demonstrated by the statistically significant correlation between NAS and SAPS II (r = .542, p = .000), as well as the result of multiple linear regression (r2 = .079, p = .000).23, 25

The original version of NAS22 and the Portuguese version of the NAS23, 25 are available in Supplementary Files 2 and 3.

4.6 Data analysis

The data were analysed using the IBM® Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software version 27.0 and Microsoft® Excel 365.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the demographic and clinical variables that characterize the study sample, with the presentation of the results in terms of absolute frequencies and respective percentages.

For the occupancy rate, length of stay, and nursing workload, we chose to use measures of central tendency, presenting the average, the SD as well as the median, the interquartile range (IQR), and the extreme values (minimum and maximum), allowing a greater understanding of the variables under analysis.

4.7 Bias

The biases are directly related to the number, type, and complexity of the patients admitted to this ICU during the data collection period. The data were collected by the principal investigator directly from the electronic health record database considering the information recorded by the different professionals during their clinical practice.

The implementation of the (Portuguese version of) NAS was suggested after a 5-year retrospective study conducted in this Portuguese ICU with TISS 28.5

The study was developed before an electronic health record update and an ICU major refurbishment that occurred in the final trimester of 2020.

5 RESULTS/FINDINGS

5.1 Sample characterization

In the 92 days (3 months) under analysis, 56 patients (study participants) were hospitalized in this ICU (Table 1). Considering demographic data, 41 participants were male (73.21%) and had an average age of 61.82 (±17.66) years. Considering the type of admission, 25 participants were admitted to the ICU through the emergency service (44.64%), followed by 17 participants admitted from the operating room (30.36%), 11 participants who were transferred from inpatient services (19.64%), and three participants transferred from other institutions (5.36%).

| Gender | n | % |

| Male | 41 | 73.21% |

| Female | 15 | 26.79% |

| Age | Years | |

| Average (±SD) | 61.82 (±17.66) | |

| Mode | 60 | |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 53|66|73.75 | |

| Minimum|maximum | 18|92 | |

| Type of admission | n | % |

| Emergency service | 25 | 44.64% |

| Operating room | 17 | 30.36% |

| Internal transfer (impatient wards) | 11 | 19.64% |

| External transfer (other institutions) | 3 | 5.36% |

| Reason for hospitalization | n | % |

| Medical problems | 33 | 58.93% |

| Surgical problems | 23 | 41.07% |

| Outcome | n | % |

| Internal transfer (ICU discharge) | 42 | 75.00% |

| Death in ICU | 13 | 23.21% |

| External transfer (other institutions) | 1 | 1.79% |

| Diagnoses (ICD-9-CM) | n | n |

| Total | 390 | |

| Mode | 7 | |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 5.75|7|8.25 | |

| Minimum|maximum | 1|14 |

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; Q1, 1st interquartile; Q2, 2nd interquartile (median); Q3, 3rd interquartile.

Although the study participants presented (multi)organic failures, the reason for admission to the ICU for 33 participants was mainly because of medical problems (58.93%).

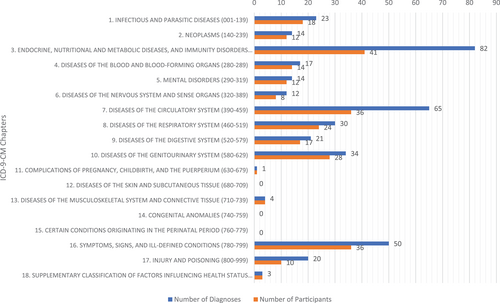

During the study period, 390 diagnoses (ICD-9-CM) were documented, namely: 82 ‘Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases, and Immunity Disorders’ diagnosed in 41 (73.21%) participants; 65 ‘Diseases of the Circulatory System’ diagnosed in 36 (64.29%) participants; 50 ‘Symptoms, Signs and Ill-Defined Conditions’ diagnosed in 36 (64.29%) participants; and 34 ‘Diseases of the Genitourinary System’ diagnosed in 28 (50.00%) participants (in this last ICD-9-CM Chapter, all the 28 participants were diagnosed with ‘Acute Renal Failure’).

Figure 1 shows the number of diagnoses recorded in each Chapter of the ICD-9-CM as well as the number of participants covered by the diagnoses of the different chapters.

Regarding the patients' outcome, 42 participants (75.00%) were discharged from the ICU to other services and/or units of lower care needs/complexity (within the same institution); 13 participants (23.21%) died during the ICU length of stay; and one participant (1.79%) was transferred to another hospital because of complications that required the intervention of an external medical specialty.

5.2 Characterization of the nursing workload

During the period under analysis, there was an average occupancy rate of 73.55% (±16.60%) and 365 assessments of the nursing workload were carried out using the Portuguese version of the NAS.

The median length of stay was 3.77 (IQR 1.83–7.82) days. In this period, the average nursing workload per participant was 67.52 (±10.91) points.

Considering the 56 participants in this study, the average of the first nursing workload assessment per participant was 80.67 (±10.89) points and the average of the last nursing workload assessment per participant was 78.08 (±10.14) points. During the period under analysis, the average nursing workload in the ICU for every 24 h was 267.88 (±76.89) points. Data related to occupancy rate, length of stay, and nursing workload are available in Table 2.

| Occupancy rate in ICU | % |

| Average (±SD) | 73.55% (±16.60%) |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 66.67%|83.33%|83.33% |

| Minimum|maximum | 33.33%|100.00% |

| Length of ICU stay | Days |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 1.83|3.70|7.82 |

| Minimum|maximum | 1.01|57.26 |

| Hours:minutes:seconds | |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 43:52:30|88:41:30|187:38:45 |

| Minimum|maximum | 24:21:00|1374:11:00 |

| Nursing workload per participant during the length of ICU stay | |

| Average (±SD) | 67.52 (±10.91) |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 58.00|65.70|76.70 |

| Minimum|maximum | 49.30|130.90 |

| Nursing workload per participant within the first 24 h | |

| Average (±SD) | 80.67 (±10.89) |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 75.70|78.20|86.35 |

| Minimum|maximum | 58.00|130.90 |

| Nursing workload per participant within the last 24 h | |

| Average (±SD) | 78.08 (±10.14) |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 72.20|75.75|81.78 |

| Minimum|maximum | 63.90|130.90 |

| Nursing workload in ICU for each 24 h | |

| Average (±SD) | 267.88 (±76.49) |

| Q1|Q2|Q3 | 207.28|262.15|322.75 |

| Minimum|maximum | 111.20|457.90 |

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; Q1, 1st interquartile; Q2, 2nd interquartile (median); Q3, 3rd interquartile.

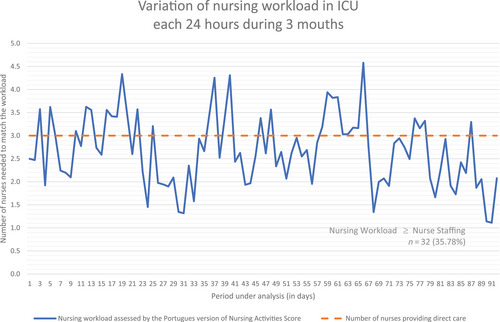

Figure 2 shows the variation of the nursing workload in the ICU for every 24 h during the 92 days under analysis.

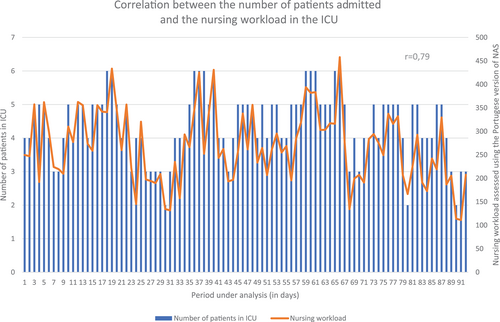

Figure 3 shows the correlation between the number of participants and the nursing workload at the ICU for each 24 h.

6 DISCUSSION

This article represents one of the first studies carried out with the Portuguese version of the NAS after its cross-cultural adaptation and validation for the Portuguese population23, 25 and the main aim was to analyse the nursing workload during a specific period, in a specific location.

6.1 Nursing workload

The average nursing workload per participant admitted to the ICU was 67.52 (±10.91) points, which shows that each participant needed an average of 16.21 (±2.62) h of nursing care per day, during the length of ICU stay.

These data are similar to the results reported in Brazilian ICUs,18, 24 Spanish ICUs,35 and Italian ICUs.28, 36 Lower results were reported in a study developed in four Portuguese ICUs23, 25 and in three Brazilian ICUs,31, 37, 38 probably because of the ICUs' heterogeneity and the characteristics of the patients admitted in those units. Higher results were reported in a study developed in six Iran ICUs32 were the authors also highlighted significant difference between the workload experienced by nurses on different work shifts (morning > evening > night).

Our data also follow the trend of the results reported by Lucchini et al.28 in Italian ICUs, where the median nursing workload per hospitalized person was 68.1 (IQR 58.3–76.6) points.

6.2 Nursing workload in the first 24 h

Analysing the data related to the first 24 h in ICU, the average of the nursing workload per participant rises to 80.67 (±10.89) points, which shows that the care provided in the first 24 h ‘consumes’ an average of 19.36 (±2.61) h of nursing care.

This increased nursing workload in the first 24 h of ICU stays (compared with the average nursing workload per participant during the length of stay) was already described in a study developed in four Portuguese ICUs.23, 25

A multicentre study developed by Padilha et al.34 with 758 participants in 19 ICUs of 7 countries recorded an average nursing workload per participant in the first 24 h of hospitalization of 72.81 (±31.10) points. Although the global average is lower than the average reported in our study, the values found vary between 44.46 (±13.00) points in the Spanish ICUs and 101.81 (±31.30) points in the Norwegian ICUs.

In the study developed by Lucchini et al.28 in Italian ICUs, there was also a higher workload per participant in the first 24 h of UCI stays compared with the rest of the hospitalization period, with a median of 69.8 (IQR 56.2–82.9) points in the first assessment.

6.3 Nursing workload in the last 24 h

Considering the data related to the last 24 h in ICU, the average of the nursing workload per participant is 78.08 (±10.14) points, which shows that the care performed in the last day of ICU stay ‘consumes’ an average of 18.74 (±2.43) h of nursing care.

Although a Sweden study highlighted that the discharge of patients from the ICU to a general ward represents a challenging transition of care,39 we did not find any reference that specifically discussed the nursing workload generated in the preparation and execution of this process. In our study, the nursing workload in the last 24 h was higher than the average of the remaining days of hospitalization (except for admission day) most likely because of the ‘administrative and management activities’ related to the ‘patient discharge procedures’ whose score was reflected in the assessment instrument used.

6.4 Variation of nursing workload in the ICU

The nursing workload in the ICU for every 24 h varied over the study period with no specific pattern but with a direct correlation with the occupancy rate.

According to National Regulations, the calculation for safe ICU nurse staffing should take into account the typology of each unit and patients' (clinical) characteristics.19 Considering the number, type, and complexity of the patients admitted in this ICU (and the typology and characteristics of this ICU by itself), our data showed that there were 32 days (35.78%) where the nursing workload assessed by NAS was higher than the available human recourses, overloading nurse staffing, and with the risk of compromising patient safety.

The task force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine propose a categorization of ICUs in three levels, based on a variety of parameters that reflect the potential of the unit to provide excellent and expert care to the most acute seriously ill patients.40

Based on that classification, ‘Ordem dos Enfermeiros’ (National Nursing Council) recommended that: ‘Primary (level 1) ICUs’ should have a nurse to patient ratio of 1:3; ‘Secondary (level 2) ICUs’ should have a nurse to patient ratio of 1:2; and ‘Tertiary (level 3) ICUs’ should have a nurse to patient ratio of 1:1.19

Thus, our data showed that the implementation of those recommendations/ratios may contribute to safer nurse staffing (despite of nursing workload variations reported during the study period) and may improve patient safety in this Tertiary (level 3) Portuguese ICU.

However, some authors highlight the need to look preferentially at the nursing workload that each participant generate29 and at the specificities of each shift,27, 32 instead of calculating nursing ratios according to occupancy rates, average nursing workload per participant, and/or the total 24-h nursing workload in ICU.

7 LIMITATIONS

This study only analysed the data of one six bed Portuguese ICU, with a small sample, over a short timeframe. Furthermore, we recognize that NAS is not a perfect tool, it only assesses 80.8% of nursing activities and does not consider the time spent in the student orientation process and/or the time dedicated for the placement and removal of advanced personal protective equipment (for example).

Although we are in a COVID-19 pandemic period, this ICU had no indication to receive any person infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the study period.

8 RECOMMENDATIONS OR IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND/OR FUTURE RESEARCH

The systematic assessment of nursing workload throughout (the Portuguese version of) NAS allows the identification of patients and/or periods with higher care needs and could be a good management tool in intensive and/or intermediate care units.

This study analysed (retrospectively) the nursing workload in a Tertiary (level 3) Portuguese ICU over 3 months and reinforces the need to take into account the National Regulations in order to ensure safe ICU nurse staffing.19

The NAS is not a perfect tool. Like other assessment tools, the NAS could be improved based on the clinical, technological, and organizational evolution.41 Therefore, we should pay attention to the patients' characteristics and to the (new) technological and epidemiological challenges42, 43 that could increase the nursing workload such as patients with renal replacement therapies,44 submitted to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation28 and/or infected with SARS-CoV-2.43, 45-49

Further studies in Portuguese intensive and intermediates care units are needed to understand the correlation between different variables of interest and better characterize the specificity and the nursing workload in caring for people in critical situations and/or (multi)organic failure in our country.

9 CONCLUSION

This study represents one of the first studies carried out with the Portuguese version of the NAS after its cross-cultural adaptation and validation for the Portuguese population. It represents the starting point for other studies carried out in the national context related to the assessment of different factors that influence the nursing workload in ICUs of different levels and typologies.

The nursing workload reported in this study follows the trend of international studies and the results found to reinforce the importance of adjusting the nursing staffing to the complexity of care and, consequently, to the nursing workload assessed for each patient in the ICUs.

During the period under analysis, the nursing workload assessed by the Portuguese version of the NAS was higher than the available human resources in 35.78% of the days, overloading nurse staffing with the risk of compromising patient safety.

At the patient level, the nursing workload in the first and in the last 24-h of ICU stays were higher than the average of the remaining days of ICU stays.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pedro Miguel Garcez Sardo: Conceptualization; methodology; investigation; formal analysis; writing—original draft; visualization; writing—review and editing; project administration. Rui Pedro Antunes Macedo: Validation; resources; writing—review and editing. José Joaquim Marques Alvarelhão: Methodology; formal analysis; writing—review and editing. João Filipe Lindo Simões: Methodology; writing—review and editing. Jenifer Adriana Domingues Guedes: Methodology; writing—review and editing. Carlos Jorge Simões: Supervision; writing—review and editing. Fernanda Príncipe: Supervision; writing—review and editing; project administration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the nursing team of the intensive care unit, Centro Hospitalar do Baixo Vouga, Aveiro, Portugal.