Barriers and perceived benefits of early mobilisation programmes in Dutch paediatric intensive care units

Abstract

Background

Early mobilisation of critically ill adults has been proven effective and is safe and feasible for critically ill children. However, barriers and perceived benefits of paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) staff involvement in mobilising critically ill children are largely unknown.

Aim

To explore the barriers and perceived benefits regarding early mobilisation of critically ill children as perceived by PICU staff.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey study among staff from seven PICUs in the Netherlands has been carried out.

Results

Two hundred and fifteen of the 641 health care professionals (33.5%) who were invited to complete a questionnaire responded, of whom 159 (75%) were nurses, 40 (19%) physicians, and 14 (6%) physical therapists. Respondents considered early mobilisation potentially beneficial to shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation (86%), improve wake/sleep rhythm (86%) and shorten the length of stay in the PICU (85%). However, staff were reluctant to mobilise patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (63%), and patients with traumatic brain injury (49%). Perceived barriers to early mobilisation were hemodynamic instability (78%), risk of dislocation of lines/tubes (74%), and level of sedation (62%). In total, 40.3% of PICU nurses stated that physical therapists provided enough support in their PICU, but 84.6% of the physical therapists believed support was sufficient.

Conclusion

Participating PICU staff considered early mobilisation as potentially beneficial in improving patient outcomes, although barriers were noted in certain patient groups.

Relevance to clinical practice

We identified barriers to early mobilisation which should be addressed in implementation research projects in order to make early mobilisation in critically ill children work.

What is known about the topic

- Early mobilisation is safe and feasible in critically ill children.

- Early mobilisation has the potential to improve the outcomes of critically ill children.

What this paper adds

- Respondents have a positive view of early mobilisation and consider it potentially beneficial to improve patient outcomes.

- Perceived barriers to early mobilisation perceived by PICU staff are hemodynamic instability, risk of dislocation of tubes and/or lines and level of sedation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Children admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) are often immobile due to critical illness and interventions such as invasive mechanical ventilation. Immobility is associated with complications including muscle weakness, pressure ulcers, and venous thromboembolism that may prolong the length of stay in the PICU.1-4

Research in critically ill adult patients has shown that early mobilisation results in better outcomes—for example, reduced incidence of ICU-acquired weakness, shorter length of staying in the ICU and hospital, shorter duration of mechanical ventilation, and improved muscle strength and functional abilities.5-8 Early mobilisation encompasses interventions that aim to maintain or restore musculoskeletal strength in critically ill patients within 72 h of their admission, including those patients on invasive mechanical ventilation.9 Early mobilisation of critically ill children has been proven safe and feasible, with the potential to shorten both hospital and PICU length of stay.10-17

2 BACKGROUND

The implementation of early mobilisation programmes in PICUs may be hampered by PICU staff's concerns about the risk of endotracheal tube dislodgement and loss of indwelling central venous catheters9 as well as the lack of sufficient equipment and perceived increased workload.18 Most of the studies investigating PICU staff's views on early mobilisation are from North America.9, 18-21 Mobilisation of critically ill children is a multidisciplinary effort of nurses, physical therapists and physicians.22 Therefore, it is essential to understand the perceived barriers of PICU staff regarding early mobilisation in relation to the context in which they are embedded.23 To date, limited information is available about what barriers PICU staff perceive regarding early mobilisation programmes in Dutch PICUs.17

3 AIM

To address this knowledge deficit, we explored the perceived barriers and benefits regarding early mobilisation of critically ill children by PICU staff in the Netherlands.

4 DESIGN AND METHODS

The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Survey (CHERRIES)24 was used to report this study.

4.1 Study design

In this cross-sectional survey study, a questionnaire was disseminated to the staff (i.e., PICU nurses, physical therapists and physicians) of Dutch PICUs (Appendix S1).

4.2 Setting

The PICUs of the seven university medical centre children's hospitals in the Netherlands—with a total of 83 beds—were invited to participate. Five PICUs are stand-alone units; the other two are part of an adult ICU, and some nurses rotate between the PICU and adult ICU. The PICUs differ in size, ranging from 8 to 24 beds. All PICUs have a mixed population, although specific critical care may be concentrated in one, for example, post-cardiac surgery care. All PICUs provide care to patients ranging in age from 0 to 18 years. Nurses working in the PICU have a bachelor's degree in nursing with additional training in paediatrics and paediatric intensive care nursing. The medical care is provided by (fellow) paediatricians-intensivists, supported by dedicated health care professionals, such as physical therapists specialised in paediatric intensive care. Three out of the seven PICUs have a protocol regarding early mobilisation. One PICU is currently working on a protocol prior to the implementation of an early mobilisation program. None of the PICUs has a PICU-dedicated physical therapist.

4.3 Sample

All PICU nurses, Advanced Practice Providers (including physician assistants and nurse practitioners), (fellow) paediatricians-intensivists and physical therapists of the seven PICUs were eligible to participate in the study. Nurse managers were excluded, as they lacked bedside experience in the mobilisation of critically ill children.

4.4 Ethical considerations

The Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres, location AMC decided that ethical approval of this study was not required as per the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (Reference W20_206#20.241). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the participants could withdraw at any moment prior to the submission of their responses. Consent to participate in the study was implied by participants' contribution to filling out the questionnaire. All data were collected, analysed and reported anonymously, in compliance to the EU General Data Protection Regulation.

4.5 Survey development

Because a validated questionnaire on the study topic was not available, five experts with expertise in paediatric critical care and survey research developed a 17-item pertinent questionnaire. The items were selected on the basis of a review of the literature on early mobilisation,9, 18-20, 22 and categorised into four parts. The first part concerned participants' demographics, such as age, sex, and years of working experience in a PICU. The second part invited the participants to indicate what patient-related factors (e.g., underlying diagnosis and physical condition) they considered relevant for early mobilisation. The third part dealt with the structural and process factors potentially influencing early mobilisation, such as time investment, workload and human resources. The fourth part is intended to get an impression of the PICU culture regarding early mobilisation by asking participants to rank possible barriers, reflecting PICU culture, in order of importance. Responses could be given on a five-point Likert scale, to make a selection of multiple answer options, and to rank possible barriers in order of importance. Furthermore, additional information or clarification could be given in the free text.

A pilot test was performed among eight PICU health care professionals (PICU nurses, physicians and physical therapists) from two PICUs to assess the clarity, comprehensiveness and face validity of the questionnaire. On the basis of their feedback, the research team saw the occasion to make some adjustments to the final questionnaire. Data from the pilot test were not used in the final analysis.

4.6 Data collection

We used LimeSurvey (version 2.6.7, built on SondagesPro 1.7.3) as an online survey tool. The nurse managers of the PICU were informed about the objectives and logistics of the study, distributed the survey among PICU nurses, physicians and physical therapists via email, and were asked to stimulate participation. In addition, the Dutch PICU research network of paediatrician-intensivists distributed the questionnaire among their members. All eligible participants were informed about the objectives of the study, their voluntary and anonymous participation, and their time commitment. This information was provided as well in the introduction to the questionnaire. The survey was open for eligible participants to respond between January 2021 and April 2021. Participation was only possible via the online survey. To increase response rates, the nurse managers were sent a reminder every week via email, to a maximum of three times, with information about their current response rates.25 We also sent reminders via email to medical directors and the Dutch PICU research network to increase the response rate among the physicians. No incentives were offered.

4.7 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographics of the respondents and the survey results. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, the mean and standard deviation are presented; otherwise, the median and interquartile ranges are presented. Frequencies and percentages are used to summarize categorical data. All data were analysed with the software package R Statistics™ Version 1.3.1093 for Windows. Only completed questionnaires were analysed.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Characteristics of respondents

In total, emails were sent to 641 health care professionals, of whom 215 responded (153 nurses, 40 clinicians, and 13 physical therapists). The total response rate was 33.5% and varied between 11.5% and 64.3% per PICU. The majority of the respondents were female (87.4%), and 56.3% had more than 10 years of experience working in the PICU. The characteristics of the respondents are further detailed in Table 1.

| Variable | N = 215 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Profession | ||

| Nurse | 153 | 71.2 |

| Physician | 40 | 18.6 |

| Physical therapist | 13 | 6.1 |

| Othera | 9 | 4.2 |

| Age | ||

| 20–30 years | 23 | 10.7 |

| 31–40 years | 62 | 28.8 |

| 41–50 years | 46 | 21.4 |

| 51–60 years | 66 | 30.7 |

| >60 years | 18 | 8.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 27 | 15.6 |

| Female | 188 | 87.4 |

| Years of experience | ||

| <1 year | 12 | 5.6 |

| 2–4 years | 35 | 16.3 |

| 5–9 years | 47 | 21.9 |

| >10 years | 121 | 56.3 |

| Percentage of employment | ||

| 100%–75% | 135 | 62.8 |

| 74%–50% | 53 | 24.7 |

| 49%–25% | 15 | 7.0 |

| <25% | 6 | 2.8 |

| On demand | 6 | 2.8 |

- Abbreviation: PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

- a Physician-assistant/nurse practitioner, circulation/ventilation practitioner.

5.2 Patient-related factors

All respondents (100%) perceived early mobilisation as beneficial to critically ill children's health. Nearly all respondents agreed that critically ill children can be mobilised by sitting in a chair (98.6%), sitting in bed with support (97.2%), and sitting on the edge of the bed (92.6%) (Table 2). Respondents also suggested mobility activities such as playing volleyball with a balloon in bed, swimming, active therapy in bed, and virtual play in bed. The perceived benefits of early mobilisation are a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation (86%), improved wake/sleep rhythm (86%) and a shorter length of stay in the PICU (85%). These results are summarised in Figure 1. According to the respondents, the children who would benefit most from early mobilisation are those with a long length of stay (94%) and those on mechanical ventilation (79.1%).

| Mobilisation in the PICU consists of | N = 215 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sitting in a chair | 212 | 98.6 |

| Sitting in bed with support | 209 | 97.2 |

| Sitting on the edge of the bed | 199 | 92.6 |

| Alternating position | 186 | 86.5 |

| Passive mobilisation | 183 | 85.1 |

| Stand up beside the bed | 182 | 84.7 |

| Cycle in bed | 176 | 81.9 |

| Play on a play mat | 174 | 80.9 |

| Walk around the bed | 166 | 77.2 |

| Walk around the ward | 133 | 61.9 |

- Abbreviation: PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

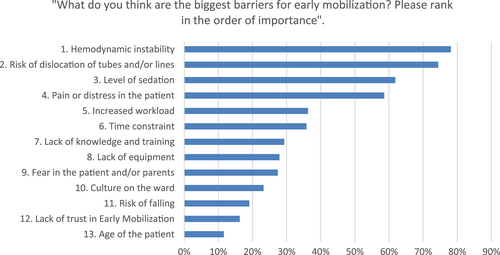

The most important reported barriers at the patient level were hemodynamic instability (78%), the risk of dislocation of vascular catheters and endotracheal tubes (74%), and the level of sedation (62%). Over half of the respondents (62.8%) were reluctant to mobilise children on ECMO, and 49.3% believed it was too dangerous to mobilise traumatic brain injury patients. In free text, several respondents reported they were also reluctant to mobilise children in the acute phase of admission. The reported barriers are ranked in order of perceived importance in Figure 2.

Eighty percent of the respondents perceived that mobilisation of intubated patients, in general, is safe, and 87.4% found it safe to mobilise mechanically ventilated children from the bed to a chair with the help of equipment and support of a physical therapist. The vast majority of the respondents (98.1%) believed it is safe to mobilise all age groups of critically ill children on non-invasive ventilation, and 81.4% believed it is safe to mobilise all age groups of intubated children.

5.3 Structural factors

Only 40.3% of PICU nurses believed there was enough support from physical therapists in their PICU, but 84.6% of the physical therapists believed their support was sufficient. Of the respondents, 56.7% thought that the appropriate equipment for mobilisation was missing from their PICU. Of the respondents, 66.1% disagreed when asked if mobilising patients is physically too demanding for them.

5.4 Process and culture-related factors

When the respondents were asked to rank barriers to early mobilisation in order of importance, time pressure and increased workload were ranked in the sixth and seventh places, respectively; lack of knowledge and training in the tenth place, culture on the ward in the eleventh place, and the health care team lacking trust in the benefits of mobilisation is in the twelfth place (Figure 2).

6 DISCUSSION

With this study, we aimed to explore the perceived barriers and benefits among PICU staff regarding early mobilisation of critically ill children in PICUs in the Netherlands. The questionnaire results show that the respondents have a positive viewpoint on early mobilisation and believe that early mobilisation can improve critically ill children's outcomes. These results are consistent with the results from earlier studies.9, 17, 21, 26 In our study and earlier studies, the most important barriers to early mobilisation are patient-related factors: hemodynamic instability, the risk of dislocation of endotracheal tubes and vascular catheters and the level of sedation of the patient. It has been shown that early mobilisation of critically ill children is safe and feasible when these patient-related barriers are accounted for in guidelines that clearly state the way in which certain children preferably should be mobilised.27 Over half of the respondents in our survey reported a lack of appropriate equipment for mobilisation in their PICU. Yet, this was not ranked as an important barrier, whereas patient-related factors were perceived as more important barriers. This contrasts with earlier studies that reported that PICU staff considered the lack of equipment, increased workload and the lack of practice guidelines to be significant barriers to early mobilisation.18, 26, 28, 29

6.1 Application to practice

The implementation of an early mobility programme for critically ill children in a PICU needs to overcome local barriers and benefit from facilitators. At this time, there is a discrepancy in the perceived level of support from physical therapists between physical therapists and PICU nurses in the Netherlands. Clearly, the implementation and evaluation of any early mobilisation programme would benefit from addressing these issues. In our belief, a PICU-dedicated physical therapist who coordinates mobilisation therapies in all patients could be a facilitator for early mobilisation in the PICU, although this is yet to be proven.30, 31 Also, clear guidelines can help PICU staff determine whether a patient can be mobilised and to what extent, with clear criteria with regard to patient-related factors to address patient-related barriers.19, 27 Also, as part of the implementation plan, an education programme for PICU staff with simulation sessions addressing barriers can improve their performance in the actual clinical setting.13 The lack of equipment for early mobilisation was not considered an important barrier in our study. However, having access to sufficient equipment could facilitate the implementation of early mobilisation and increase mobility levels.19, 32 In addition, appointing local champions among PICU nurses and physical therapists could help motivate PICU nurses to perform more early mobility activities and empower parents to help with mobilising their children.19

6.2 Limitations

Several limitations of this study need to be addressed. First, because our study focused on the barriers and perceived benefits of early mobilisation among PICU staff, no specific questions about facilitators were included in the questionnaire. Second, the structural and cultural differences between PICUs were assessed superficially, and therefore, it is difficult to draw hard conclusions about any differences between Dutch PICUs. Therefore, local barriers need to be re-assessed before implementing an early mobilisation programme that can be appropriately evaluated in any of the PICUs. Third, the low overall response rate of 33.5%, varying between 11.5% and 64.3% per PICU, could have introduced nonresponse bias. However, evidence suggests that there is no statistically significant relationship between response rate and nonresponse bias.33 Fourth, in the instructions for the participants, the definition of early mobilisation was given, but without the timeframe of 72 h. The definition of EM might not have been totally clear for the participants, which could have influenced their answers. Last, we used a non-validated, self-constructed questionnaire because a validated tool was not available for this topic. However, we developed the questionnaire with the help of five experts in survey research and paediatric critical care and based on previous research.9, 18-20, 22

6.3 Future research

To increase mobility levels in critically ill children and potentially improve patient outcomes in the short and long term, future research should focus on reducing the influence of the barriers identified in this study. In addition, future research should focus on ways to identify children at risk for poor short- and long-term outcomes and who would benefit most from mobilisation interventions. Lastly, several interdisciplinary aspects of early mobilisation should be addressed, such as delineating the roles and responsibilities of the various disciplines involved in early mobilisation and considering a possible role for parents/caregivers.

7 CONCLUSION

PICU staff in the Netherlands consider early mobilisation of critically ill children admitted to the PICU as potentially beneficial to improve patient outcomes. According to the respondents, early mobilisation can shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation, improve the wake/sleep rhythm and shorten the length of stay in the PICU. We identified patient-related barriers to early mobilisation that should be addressed in implementation strategies in order to be able to scientifically evaluate the effects of early mobilisation in critically ill children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the medical directors and nursing managers of the Dutch PICUs for distributing the questionnaire; the Dutch PICU research network of paediatrician-intensivists for motivating their members to participate; and all the respondents for giving their input. The authors thank Ko Hagoort for editing the manuscript.