The content of school textbooks in (nation) states and “stateless autonomies”: A comparison of Turkey and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (Rojava)

Abstract

Highlighting the modernity of state institutions, Hobsbawm defines the nation as a modern territorial state (the nation-state) and argues that nation and nationality cannot be discussed unless they refer to the nation-state. Hobsbawm's conception of nations and nationality in the context of the nation-state warrants readdress by comparing Westphalian models of states with subjects that do not attempt a territorial model but arguably still invest in the nation and a sense of nationality. This article compares the discourses of building nations and national identities fostered in the content of school textbooks in the Republic of Turkey—a modern, territorial nation-state—and the Autonomous Administration of North and East of Syria (hereafter Rojava)—an alternative state system model established in the power vacuum proceeding Bashar al-Assad regime withdrawal from expansive territory in northern Syria. In doing so, the article revisits the existing literature on the correlation between the content and political associations of school textbooks through a comparative analysis of primary school course materials in Turkey and Rojava, neighbouring and conflicting political entities that occupy contrasting domains of statehood and military capacity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Along with the sounds of bombs come gunshots. More like rifles. Tak tak tak tak tak … Teachers are quick in trying to usher the children inside from the schoolyard. They just entered their class. They will study maths, science, and history amongst the bombings. A history that does not belong to them.1

(Baysal, 2018, p. 9)

There exists a vast body of literature which describes schools as spaces of indoctrination, the reproduction of class inequality, and the transmission of collective identity (Althusser, 1971; Bourdieu, 1973; Foucault & Nazzaro, 1972; Gramsci & Lawner, 1979). In Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, Althusser (1971, p, 133) argues that, like other institutions of the state such as the church and the army, schools are domains that “ensure subjection to the ruling ideology or the mastery of its ‘practice’.” Schools and educational structures, for Foucault (2003, p. 45), are “apparatuses of domination” or, in Deacon's (2006, p. 181) words, “a disciplinary response to the need to manage growing populations.”

Textbooks have become crucial sources for researchers as “(t)hey always contain and enshrine underlying norms and values, they transmit constructions of identity, and they generate specific patterns of perceiving the world” (Fuchs & Bock, 2018, p. 1). Aiming to provide a coherent synopsis of textbook studies and its comparatively diverse “thematic emphases, theoretical approaches, and methodological procedures,” Fuchs and Bock's (2018, p. 2) handbook delves into the content of textbooks, discussing their construction of identities and their representations and depictions of the past.2

Theories on nationalism also highlight the role of schools and education in nation-states (Anderson, 2006; Gellner, 1983, 1987; Hobsbawm, 1992). Gellner (1987, p. 24) addresses the transformation from an agricultural to an industrial economic system and how this necessitated the bonding of the masses through shared language, memories, myths, or what can be generalised as “cultural standardisation” or homogenisation. Education and schooling were pivotal in fulfilling this need. Referencing Max Weber's depiction of the state as having a “monopoly of legitimate violence”, Gellner writes, “The monopoly of legitimate education is now more important, more central than is the monopoly of legitimate violence” (Gellner, 1983, p. 34). Like Gellner, Ingrao (2009, p. 181) correlates education and violence, describing school textbooks and classroom instruction as “weapons of mass instruction,” which, along with childhood religious instruction and television, “provide the first imprint on our memory at a time when we are least capable of distinguishing fact from fiction.”

Studies on the role of education and school textbooks in constructing nations and national identities have concentrated on cases in Latin America (Grosvenor, 1999; Levinson, 2001; Nava, 2006; Vom, 2009), Asia (Guichard, 2012; Lu, 2016; Vickers, 2002), Europe (Faas & Ross, 2012; Jaskułowski, Majewski, & Surmiak, 2018; Pavasović Trošt, 2018; Schissler & Soysal, 2005; Ververi, 2017; Zembylas, 2010), and the Middle East (Adwan, Bar-Tal, & Wexler, 2016; Koullapis, 2002; Nasser, 2004; Ram, 2004; Tejel, 2015; Vural & Özuyanık, 2008). Schissler (2009a, p. 24) argues that history textbooks have become “sources of collective memory” and “autobiographies of nation states.” She describes history, geography, and civics textbooks as “excellent sources for analyzing the normative structures of societies” and signifying “social consensus as well as conflict lines in society” (Schissler, 2009b, p. 205). In their comparison of the portrayal of “the other” in Palestinian and Israeli school textbooks, Adwan et al. (2016, p. 202) designate schools and textbooks as “primary vehicles and venues through which societies formally, intentionally, systematically and extensively impart national narratives, having the authority, legitimacy, means, and conditions to carry it out.” Adwan et al. (p. 202) also argue that school curricula demonstrate “a society's ideology and ethos and imparts values, goals, and myths which the society aims to transmit to new generations.” Schools thus become the “highly visible ‘political hand’ of state textbook-adoption policies” (Apple, 1992, p. 6). The literature includes studies that compare national identity making in the content of school textbooks in Turkey and Greece (Dragonas, Ersanli, & Frangoudaki, 2005; Millas, 1991) and in Turkey and Armenia (Akpınar et al., 2019; Sayan, Karapetyan, Gamaghelyan, & Bilmez, 2019) as neighbouring countries historically embroiled in conflict.

Highlighting the modernity of state institutions, Hobsbawm (1992, pp. 9–10) defines the nation as “a social entity only insofar as it relates to a certain kind of modern territorial state, the ‘nation-state’, and suggests that it is pointless to discuss nation and nationality except insofar as both relate to it.” He argues that “nations exist not only as functions of a particular kind of territorial state or the aspiration to establish one (…) but also in the context of a particular stage of technological and economic development” (Hobsbawm, 1992, p. 10). Hobsbawm's stance warrants readdress, hereby comparing a nation-state with a political community that does not attempt a territorial state model but still invests in the idea of the nation and in a sense of nationality. This article compares the treatment of national identities in school textbooks in the Republic of Turkey—a modern, territorial nation-state—and the Autonomous Administration of North and East of Syria (NES, hereafter Rojava)3—an alternative state system in northern Syria. It provides new empirical information on the existing literature on nations and nationalism. It also revisits the existing literature on the nationalist content school textbooks through a comparative analysis of primary school course materials in Turkey and Rojava, neighbouring entities with contrasting degrees of statehood and military capacity.

1.1 The political conflict between Rojava and Turkey

After the eruption of the Syrian civil war, in 2014, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and allied groups established three cantons: Cezîre (Jazirah), Kobanî (Ain Al-Arab), and Efrîn (Afrin). The Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS) was declared in 2017 in the part of Kurdistan—divided between Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq—that Kurds refer to as Rojava (Western Kurdistan). The DFNS changed its name in early 2019 to the Autonomous Administration of NES. Regardless of its names, it implements the “democratic confederalism” model fashioned by the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), Abdullah Öcalan. Öcalan (2017, p. 21) defines the model as “a non-state political administration or a democracy without a state.” The Social Contract of Rojava4 then defines the Democratic Autonomous Regions (and the DFNS) as a confederation of Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians, Chechens, Circassians, (…) Muslims, Christians, Yazidis, and various other creeds and sects that pursue “freedom, justice, dignity and democracy,” “led by principles of equality and environmental sustainability.” The contract also supports the protection of “fundamental human rights and liberties the peoples' right to self-determination,” the unification of people “in the spirit of reconciliation, pluralism and democratic participation so that all may express themselves freely in public life,” as well as the enforcement of gender equality and feminism (YPG International, 2016).

The Turkish government has opposed any emergent form of Kurdish self-rule since the eruption of the civil war in Syria in 2011. It considers the PYD the Syrian extension of the PKK/KCK, with which it has maintained an ongoing armed struggle since 1984.5,6 In 2018, Turkey launched attacks against Rojava—then called the DFNS—in Afrin. In October 2019, Turkey initiated reinvigorated military operations in northern Syria, claiming that it sought “to prevent the creation of a terror corridor across our southern border, and to bring peace to the area” (Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, Directorate of Communications, 2019). This prompted the Rojava administration to negotiate with the al-Assad regime, bringing a “bitter end to five years of semi-autonomy” in Northern Syria (The Guardian, 2019). The AKP government has veered sharply towards an authoritarian disposition in its domestic politics as well, especially after the abrupt end of peace talks with the PKK in June 2015 and the failed July 15 2016 coup attempt against its government. Some interpret this as a new era defined by an “exit from democracy” (Öktem & Akkoyunlu, 2016) or a “return of militarism” (Turan, 2019). Jongerden (2019, p. 270) critiques the turn idea arguing that earlier “reforms often held up as a ‘democratization’ were rather instruments opportunistically employed in the AKP struggle to conquer the state.” One result of the AKP's authoritarian turn was the uses of the terrorist label against opposition groups, including legal parties such as the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) and the Democratic Regions' Party (DBP).

This paper compares the content of school textbooks in Turkey and Rojava. Such a comparison has something to say on the accusations Turkey lobs at Rojava of being a “terrorist corridor,” while the Rojava administration emphasises their desire “to have neighbourly relations with Turkey and respect each other's rights” (Rudaw, 2019). Existing studies on Turkey and Rojava concentrate on conflict and politics, especially the Kurdish movement's proposed democratic autonomy model (Leezenberg, 2016) and the social ecology policies the Kurdish movement implemented in Turkey and Syria (Hunt, 2017). This study, however, compares the two political entities in terms of their utilisation of school textbooks to create “collective memory and consciousness” or a “we” feeling within the young generation (Schissler, 2009b, p. 204).

I proceed with a brief review of the literature on educational models and textbook content in Turkey and Rojava. I then continue with the methodology section, followed by the analysis of some primary school textbooks from Turkey and Rojava. Finally, I conclude with a discussion of the findings and their implications.

2 THE LITERATURE ON THE EDUCATIONAL MODEL IN ROJAVA AND THE KURDISH IDENTITY IN TURKISH SCHOOL TEXTBOOKS

In the early 1990s, Öcalan proposed the private teaching of the Kurdish language. The establishment of a specific school system in the Maxmur refugee camp followed. For several years, the Maxmur camp provided the primary infrastructure for the training of teachers and the translation of textbooks into Kurdish (Kurmanji). The subsequent Rojava “revolution” legalised the open instruction of Kurdish in the cantons, “blossoming the Kurdish language instruction” that was banned under the Ba'athist regime in Syria (Knapp, Flach, & Ayboga, 2016, pp. 175–176). Instruction in other native tongues such as Syriac and Arabic was also legalised.7

Although the literature on Rojava's education model is understandably sparse, the Rojava experience in Northern Syria constitutes a revolutionary project (Dirik, Strauss, Taussig, & Wilsin, 2016; Graeber, 2014; Knapp et al., 2016; Ross, 2017; Savran, 2016; Schmidinger, 2018). It is claimed to be both a political and a “mental revolution” (Duman, 2016; Knapp et al., 2016; Üstündağ, 2016). Two comprehensive studies by Knapp et al. (2016) and Duman (2016) suggest Rojava's ambitions for “the democratisation of education.” Reforming the language of instruction from only Arabic to Arabic, Kurdish, and Syriac, altering the content of schoolbooks, decentralising educational administration, and facilitating nonhierarchical classroom interactions between students and teachers became central to Rojava's democratisation of education.

A similar approach is evident in the nonacademic world. Biehl (2015) contends that the canton's education system is pursuing a transition from the authoritarian mentality under the Ba'ath regime and its nationalistic focus towards a revolutionary approach, aiming to “create free individuals and free thoughts.” Executives of the Democratic Society Movement (TEV-DEM)—the umbrella coalition that acts as a third-party mediator between the governing Democratic Syrian Council and the NES—stress the importance of education in the success of the political project they are trying to adopt in Rojava. Salih Muslim, the former copresident of the PYD and current member of TEV-DEM's International Diplomacy Committee, emphasised the necessity of developing capacities and skills for collective discussion and decision making through education: “You have to educate, twenty-four hours a day (…) you have to reject the idea that you have to wait for some leader to come and tell the people what to do, and instead learn to exercise self-rule as a collective practice” (Biehl, 2015). Another TEV-DEM council member Aldar Xelil stated that the system in Rojava “is not just about changing the regime but creating a mentality to bring the revolution to the society” (Biehl, 2015). The Rojava administration has repeatedly claimed to be a part of Syria and to desire a democratic Syria that facilitates the peaceful coexistence of all citizens.

In Turkey, the Ministry of National Education administers the primary and secondary education systems.8 Turkish has been the language of instruction since 1928. Scholars who explore the representation of “others”—Kurds, Alevis, and non-Muslim minorities—have conducted extensive research on the role of nationalism, identity, and citizenship in textbooks in Turkey (Çayır, 2015; Çelik, 2017; Copeaux, 2000; Somel, 2019; Yanarocak, 2016). Responding to the claim that the state and other institutions are not anti-Kurdish (Saracoglu, 2009), Karakoç (2011) claims that the education system and the media routinely inflict Turkish nationalism on society. Dixon and Ergin (2010, p. 1343) argue that “education—long thought to promote tolerance—does not shape beliefs about the Kurds” positively. Yanarocak (2016, p. 406) argues that the Kurdish identity faced constant rejection, embodied by willful ignorance, between 1924 and 1980 and continuing with the active denial of a distinct Kurdish ethnic identity from 1980 until Erdoğan's declaration of the “Peace Process” between Turkey and the PKK in 2012. Çayır's (2015, p. 531) research also demonstrates that “current textbooks (in Turkey) promote an ethno-religious (Turkish, Sunni, Muslim) national identity” that regards all citizens living in Turkey as ethnically Turkish and practicing Muslims despite 2005 reforms to comply with European Union (EU) norms.

3 METHODOLOGY AND LIMITATIONS

This research analyses content—including poems, stories, maps, images, vocabulary, and glossaries, side boxes, and exercises—from selected primary school textbooks used in Turkey and Rojava. This research was possible through the help of my colleague Dr. Mehri Ghazanjani, who had previously visited the region for fieldwork, collected school textbooks, and offered to share them with me. I received scanned versions of four books—two on social sciences and two on Kurdish grammar—from Ghazanjani in the spring of 2018. The textbooks used in Rojava were in Kurdish, and a research assistant provided the translations.9

The analysis involved an iterative process, beginning with a deductive logic in which I searched for keywords and themes that embodied the state (Turkey); the democratic autonomy model (Rojava); nation; national symbols; and other identities. From the initial readings of the data emerged new themes and keywords, such as democracy, family and household, gender, and martyrdom. In the second stage of data analysis, I used a more inductive logic, dissecting texts in terms of themes and thematic analysis. I ended up questioning whether the primary school textbooks of Rojava offer a more pluralistic approach and contrasted the two constructions of a “we” feeling. I included in Table 1 a list of the themes and keywords I used and their conceptual definitions.

| Themes/keywords | Definitions |

|---|---|

| State/nation | References to Republic of Turkey and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (Rojava) as states, governments, or administrative units and their people with a shared cultural identity |

| National symbols | National flags, emblems, maps, and leaders of Turkey and Rojava |

| National identities | Reference to national identities of Turkey and Rojava |

| Democracy | Explanation of democracy as a system of government in Turkey and Rojava |

| Family/household/motherhood | References to nuclear families, households, motherhood, and their links with democracy |

| Gender/women | Reference to gender and the role of women in national/state matters |

| Martyrdom | Concept of martyrdom and its importance for national well-being |

After the initial review of Rojava textbooks, I decided to use three books—two social science books and one grammar textbook—that were rich in the themes I was searching for. The books are Zimanê Kurdî 3 (Elementary Kurdish 3), Zanistên Civakî 4 (Social Sciences 4), and Zanistên Civakî 5 (Social Sciences 5).

I then reviewed the primary school curriculum in Turkey. Table 2 features the weekly timetable for primary school education in Turkey for the 2017–2018 academic year. Despite persistent attempts, I was unable to find or visualise a weekly timetable for primary school education in Rojava.

| Subject | Number of weekly hours in each grade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Turkish language | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Mathematics | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Knowledge of life | 4 | 4 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Science and technology | - | - | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Social sciences | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | - |

| History of reforms and Kemalism | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Foreign language | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Religious culture and ethics | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Visual arts | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Music | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Games/physical activities/sports | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Technology and design | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Traffic and first aid education | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Guidance/career planning | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Information technologies and software | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | - |

|

Human rights, citizenship, and democracy |

- | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Total number of weekly compulsory lessons | 26 | 28 | 28 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

Education is compulsory in Turkey for 12 years in a system known as “4 + 4 + 4.” Primary school education lasts 6 years in Rojava. For the sake of comparison, I decided to use the school textbooks implemented in the first 4 years of primary school education in Turkey and compare these books with the social science and civics textbooks taught in primary school in Turkey in order to maximise the content of the themes and keywords I was searching for. I excluded the grammar books taught in Turkey, as social science and civics books were available for analysis, and I decided to examine three books taught in primary school Grades 3 and 4 in Turkey: Hayat Bilgisi 310 (Knowledge of Life), Sosyal Bilgiler 4 (Social Sciences 4), Demokrasi, Yurttaşlık ve İnsan Hakları 4 (Democracy, Citizenship, and Human Rights). I also deliberately selected the textbook Democracy, Citizenship, and Human Rights produced in collaboration between Turkey and the EU. Its inclusion I believe is crucial in underscoring the influence of the EU on Turkey and highlighting the benefits the Turkish educational system has reaped from intergovernmental actors, as opposed to Rojava, which lacks international support.

I analysed six primary school textbooks (Table 3), which were approved by the educational authorities and have been in use in Turkey and Rojava since 2015.11 Despite the small sample size, this study constitutes an important contribution to the literature, as no scholarly comparison exists of the content of school textbooks in Turkey and Rojava. These two entities not only represent neighbouring yet divergent models but are also in an ongoing conflict.

| Textbook title | Grade | Acronym for textbook | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | Knowledge of Life (Hayat Bilgisi) | 3 | HB |

| Social Studies (Sosyal Bilgiler) | 4 | SB | |

| Democracy, Citizenship, and Human Rights (Demokrasi Yurttaşlık ve İnsan Hakları) | 4 | DYIH | |

| Rojava | Kurdish Language (Zimanê Kurdî) | 3 | ZK |

| Social Sciences (Zanistên Civakî) | 4 | ZC4 | |

| Social Sciences (Zanistên Civakî) | 5 | ZC5 |

Certain limitations in my research oblige disclosure. First, I was unable to travel to Syria due to the ongoing war, meaning that this paper relies only on a reading of the textbooks I was able to collect. Considering that nations are “dual phenomena” (Hobsbawm, 1992, p. 10) constructed from both above and below, this is an important limitation. Analyses that observe the movement from below would be vital in understanding how individuals perceive and experience this model and, more importantly, the demands of those residing in these cantons. Ethnographic research on educational institutions that translate and compose textbooks for Rojava and train teachers would show the intentions and practices that have materialised within this model. The ability to conduct interviews with policymakers, academies, teachers, and students in Rojava and to observe classroom interaction would also be informative. Second, although my sampling of the Turkish textbooks matches the existing textbooks I procured from Rojava, I acknowledge the bias this constitutes and the possibility that other researchers would prefer a different sampling strategy. Third is the linguistic limitation. Because I do not know Kurdish myself, I had to rely on the textbooks' translations, which were kindly performed by a research assistant and checked by Dr. Yasin Duman. The research assistant's reading of Rojava textbooks hinged on the key concepts and themes I identified. Finally, and related to the linguistic limitation, the possibility of ambiguity persists throughout the interpretation of multiple pieces of literature.

4 THE CONTENT OF SCHOOL TEXTBOOKS IN TURKEY

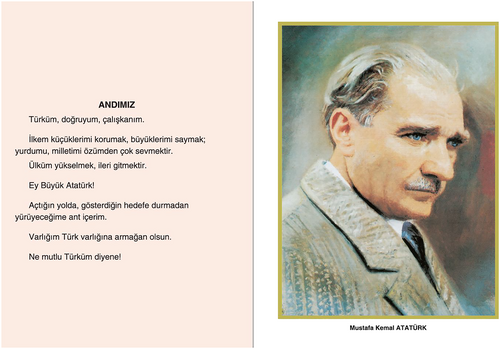

The Turkish textbooks devote their first few pages to a picture of the flag, the introductory verses of the Turkish national anthem (Figure 1), and a portrait of the founder of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, followed by either the “national oath” (HB; Figure 2) or his address to Turkish youth (SB and DYIH).

I am a Turk, honest, hardworking. My principles are to protect the younger, to respect the elder, to love my homeland and my nation more than myself. My ideal is to rise, to progress. May my life be dedicated to the Turkish existence (...) How happy is the one who says “I am a Turk!” (Genç, 2013).

In 2013, then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan abolished this obligation in primary schools under a “democratisation package.” He also agreed to some Kurdish demands, authorising native-language education in private schools and allowing the use of the letters “q,” “w,” and “x”, which do not exist in the Turkish alphabet but are present in Kurdish (The Guardian, 2013). Nonetheless, the first pages of school textbooks indicate the instrumentalisation of the national oath, flag, national anthem, and the portrait of Atatürk as emulations of national pride.

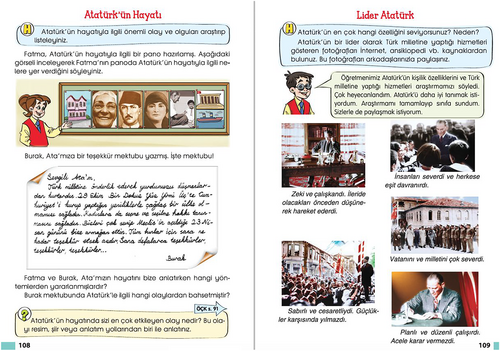

Not only do Atatürk's portrait and name appear in the first pages of the textbooks, but also sections also reference him repeatedly, evoking Anderson's (2006, p. 198) point about “the silence of the dead (being) no obstacle to the exhumation of their deepest desires” (Figure 3).

In Hayat Bilgisi, the section “Despite All” aims to instruct students not to concede defeat when facing challenged. The section begins with Atatürk's statement on schools, which reads: “School gives young minds respect for humanity, love for the nation and the country and teaches independence” (HB, p. 27). Later in the section appears, once again, a reference to Atatürk in the words of a student: “I love my school despite all the difficulties I go through. When I face a difficulty, I take Atatürk as an example/role model” (HB, p. 28). The anniversary of Atatürk's death, November 10, receives official commemoration as part of “Atatürk Week” in schools, along with other national holidays that memorialise him and his legacy (HB, p. 49).

Sosyal Bilgiler includes Atatürk's address to Turkey's youth instead of the national oath in its first pages. The section “the individual and the society” contains a heading entitled “all colours coexisting” that aims to demonstrate the possibility of physical differences between people. The section cites disabled children as an example, bolstering diversity as the wealth of society and maintaining that people should strive for mutual empathy. Another section, entitled “your turn,” tasks students with discussing the covered topic, the given example for which is from Atatürk and how he valued people; his picture accompanies the text (SB, p. 24). Demokrasi Yurttaşlık ve İnsan Hakları, which is a collaborative creation of Turkey and the EU, contains notably fewer references to Atatürk relative to Hayat Bilgisi and Sosyal Bilgiler, with only one quote attributed to Atatürk on respecting nature and the environment (DYIH, p. 217).

The word “Turkish” appears frequently in all of these textbooks in phrases such as “Turkish boys,” “Turkish girls,” “Turkish youth,” “Turkish artist,” and “Turkish nation.” The Turkish flag is highly visible throughout the textbooks in addition to the flags on the introductory pages. Demokrasi Yurttaşlık ve İnsan Hakları has a section titled “The state exists for us” (DYIH, p. 317), which venerates police authority with an example about protecting the Turkish flag. In the example, a police officer admonishes a person who attempted to remove the Turkish flag from a flagpole. But that person, whose face was covered,12 persisted and was subsequently restrained, resulting in the injury of both individuals (DYIH, p. 323). The section concludes with the sentence “The governor of the province rewarded the police officer who prevented the flag from being taken down” (DYIH, p. 323). Sosyal Bilgiler (p. 48) refers to the Turkish “national struggle”: “With the French pulling down the Turkish flag, our nation's resistance increased. The French and the Armenians had to leave Maraş (a province in south-eastern Turkey).” This passage reveres the flag as a sacred value deserving of protection, the Armenians having been an internal element of the Ottoman state and society for centuries.

The nationalist tone in the selected textbooks is evident from headings such as “Atatürk's Life,” “Atatürk the Leader,” “Our Flag,” “Our National Holidays,” and “To Sustain the Republic” (HB, pp. 108–115). The seven pages that these sections comprise incorporate seven pictures of Atatürk and more than 15 pictures of the Turkish flag. The text brims with constant references to Atatürk's role as “the leader of the Turkish nation” (HB, p. 108), how he trusted the “Turkish nation,” and how the Turkish nation must “love our country and protect our national values” (HB, p. 114).

Sosyal Bilgiler (pp. 46–52) extends its nationalist tone in the section entitled “Our National Struggle,” which begins with the occupation of the Ottoman Empire in the wake of World War I. This section contains frequent appearances of the word “enemy,” asking students to name enemy states (SB, p. 46) and to create a poster that invites “our (Turkish) nation to participate in the National Struggle” (SB, p. 47). This section refers to the Armenians in Eastern Anatolia during the 1910s and 1920s as a people “who organized attacks against our (Turkish) nation” (SB, p. 48) and colluded with French occupiers (SB, p. 48). Similarly, this section portrays Greeks as adversaries who invaded the Izmir province (SB, p. 50).

Child heroes played a key role during the struggle of independence in Maraş, which lost many of its children. Some became martyrs, and some experienced the pride of being veterans. When the French invaded Maraş, Şekerci Ökkeş's mother told him, “My son, you are young. They will shoot you down.” Ökkeş showed his bravery saying, “My age is young, mother, but my faith is big. If I become a martyr, I will be for this country and nation. I shall die, so that the enemies do not come close to you” (SB, p. 49).

This section continues with an exercise asking students to reflect on the ideas and emotions that motivated these child heroes and to consider what they, as students, would do for their country if they had lived during the years of the “national struggle” (SB, p. 49).

As a textbook Turkey prepared in collaboration with the EU, Demokrasi Yurttaşlık ve İnsan Hakları contains specific sections on human rights, equality and justice, conflict resolution, democratic society and participation, free speech, and the right to protest and environmental protection. It has references to the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Iraq, refugees, and the effects on civilian life (DYIH, pp. 120, 121, 176–186). Nonetheless, these books have no references to the events taking place in Turkey's south-east, also called Turkey's Kurdistan or Northern Kurdistan (Bakur). This contradiction, if not outright hypocrisy, deserves emphasis since the war fought between the Turkish state and the Kurdish insurgent groups between July 2015 and March 2016 left thousands of Kurdish fighters, Turkish soldiers, and civilians dead and displaced (International Crisis Group, 2016). Gellner (1987, p. 17) refers to “the anonymity, the amnesia” in nationalism, where “it is important not merely that each citizen learns the standardised, centralised, and literate idiom in his primary school, but also that he should forget or at least devalue the dialect which is not taught in school.”

5 SCHOOL TEXTBOOK CONTENTS IN ROJAVA

Textbooks in Rojava begin with two notes. The first reads “This book is used as a school textbook by the cantons of Rojava for education and learning.” And the second states “This book has benefited from Maxmur's textbooks, and it has been prepared by the committee of Books (curriculum) in Western Kurdistan.” Unlike their Turkish counterparts, Rojava textbooks begin with no flags, maps, national anthems, or oaths or portraits of leaders. They contain only an imprint that reads “Democratic Autonomy” (Xweseriya Demokratik) followed by the canton's name in Kurdish, Arabic, and Assyrian. Below the same symbol is the phrase “Education and Learning Standards” (Figure 4).

Zanistên Civakî 4 begins with a significant emphasis on the family section and the role of women for love, kindness, respect, and education for democracy. The emphasis resides heavily on the role of mothers; one section is called “Mother in the family” (ZC4, p. 7). It emphasises that “a child who grows up in a democratic family will have a strong personality. He or she becomes a human and a strong, good and free citizen” (ZC4, p. 10). The family is also described as a place “for love, relation, education, loving one's own country,13 own land, and own people” (ZC4, p. 11).

The text introduces schools as salient places for educational growth, where people learn about free and democratic life, equality, their culture and traditions (moral values), the philosophy of free life, the environment, and various fields of science. It is also where “they learn about life, reading, writing, and nature” (ZC4, p. 11). The section entitled “Equality in our school” focuses on the concepts of democracy, equality, freedom, and reciprocity. This section highlights democracy in the classroom through examples of the mutual respect between teachers and students and students' organising of committees for sanitation, health, and the maintenance of books (ZC4, p. 15).

Parts of the book, however, merit more detailed scrutiny.

The section entitled “Women's place in life and society” (ZC4, p. 22; Figure 5) depicts Leyla Qasim, a Kurdish activist executed in the struggle against the Ba'ath regime in Iraq in 1974. Her picture symbolises the endurance of the decades-long Kurdish struggle. Pictured also are Arin Mirkan, who died in a suicide attack against the Islamic State in Rojava in 2014, standing before a partly visible YPJ flag; and Zeynep Kınacı, a PKK guerrilla fighter in Turkey who also died in a suicide attack against Turkish soldiers in the Tunceli (Dersim) province in Turkey in 1996. This section aims to emphasise the “Kurdish women who have shown strong heroism in the struggle for freedom” (ZC4, pp. 22–23) and to stress that “thousands of Kurdish women have sacrificed their lives for freedom and the freedom of the Kurdish people” (ZC4, p. 23). The section concludes with this paragraph: “Today, Kurdish women have a strong and well-known organisational power. Kurdish women shared their experience with other peoples (nations) in the world and, by this, the heroism of Kurdish women has been noticed” (ZC4, p. 23). The significance of this section originates not only from its emphasis on the “Kurdish women” but also the glorification of the concept of sacrifice for “freedom,” even if this means suicide bombing.

The final section in Zanistên Civakî 4 is entitled “Important figures in the struggle for building the democratic nation” and portrays three “martyrs” (with the abbreviation Ş. for şehid, meaning martyr): Ş. Arîn Mîrkan, Ş. Temir Behdê, and Ş. Basil (ZC4, pp. 77–80). Both Mîrkan and Basil were martyrs of the YPG/YPJ. The text introduces Basil, an Arab, saying, “After his involvement in the YPG, he proceeded to expand his understanding (of the movement/ideology) and always discussed his own intellectual experience in Rojava, especially the influence of Mr. Öcalan and how he wanted to become a model/example for his brothers, six of whom later joined the YPG” (ZC4, p. 80). “Temir Behdê was an Assyrian who died for his beliefs and the honour of his Assyrian community and became a martyr” (ZC4, p. 79). Once again, there persists a glorification of death in the struggle for democracy through an emphasis on martyrdom, although this sacrifice reflects the common suffering of different ethnic or religious communities for this common objective.

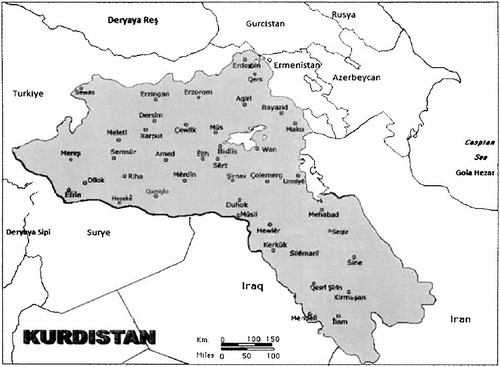

The rest of Zanistên Civakî 4 discusses the life of Kurds, who have been divided into four states and whose population is around 42 million (ZC4, p. 23). The most important cities in Kurdistan are listed as Amed in Turkey, Qamişlo in Syria, Hewlêr in Iraq, and Kirmanşan in Iran (ZC4, p. 24). The section then gives more detailed information about Kurdistan and the people of Kurdistan, their lives in villages and urban areas, their economy, geography, and nature, history and culture, and religious beliefs (ZC4, p. 26). These sections employ the word Kurdistan as a region and country and frequently refer to the Kurds as a unified people. Several maps of the greater Kurdistan area also stand out in these sections (ZC5, pp. 39, 41, 51, 83, 95; see also ZC4, p. 118; Figure 6).

In Kurdish history, we see that the state power and the powerful have implemented inhumane means against Kurdish people and their culture. This has caused a certain characteristic among Kurds. This character among the Kurds has learned to not preserve their culture and to ignore their language and tradition. It is crucial to take care for one's culture to build a strong character and awareness among societies (ZC5, p. 10).

The section that focuses specifically on the lakes and rivers in Kurdistan explains the significance of the rivers in Kurdistan as eminent resources for agriculture and energy production as well as the harm of dams that have been “built close to the ancient sites, with the purpose of destroying Kurdish culture” (ZC4, p. 54).

Zimanê Kurdî, designed as a Kurdish language grammar book, often cites Kurdistan as a land to love and protect. It contains poems such as “May it always be alive this land of Kurdistan” (ZK, p. 16) and “I am a mountain, a fountain; I am like water; I am trees and forests, valleys and hill, flowers and flower fields; I am Kurdistan” (ZK, p. 67). The second text, a single page which features several appearances of the word “Kurdistan,” culminates with the sentence “His dream, for this hardworking young man, became the foundation for patriotic organisation, and with this, the soul of youthfulness and patriotism spread in the society and started struggle for homeland” (ZK, p. 68). The subsequent vocabulary list contains the words “angel,” “maturity,” “production,” “patriotic,” “foreign,” and “struggle” for students to learn (ZK, p. 69).

To study always needs working a lot,

For the Kurdish nation and for the homeland

All Kurds must wake up

Our day has come for sure

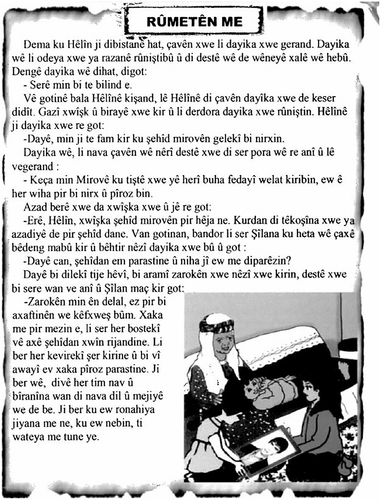

Zimanê Kurdî also contains a passage on martyrs, titled “Our Glory” (ZK, p. 29), in which the word martyr [şehîd or fedayî] appears five times on a single page. In the same section is a picture in which we see an elderly woman—a mother—surrounded by three children, one holding a framed picture of a martyr (ZK, p. 29; Figure 7). The text illustrates the story of a girl named Hêlîn who goes home to converse with her mother about the valour of martyrs and the value of their sacrifice. The mother responds, stressing the greatness of martyrs who fought and died for freedom (ZK, p. 29). The subsequent vocabulary list contains the words “glory,” “martyr,” “leadership” (Öcalan), and “history” (ZK, p. 30).

6 SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

I have compared primary school textbooks in Turkey and Rojava, two political administrative units with very unequal statehood capacities involved in the same enduring conflict. The findings indicate that, regardless of their actual degree of statehood, both entities utilise primary school education in the construction of a “we” feeling based on their dominant national ideologies. Certain similarities and differences in the content of these textbooks are however worth stressing.

First, the textbooks from Turkey, being an established state, contain numerous references to the nation's flag and founder Atatürk, whereas Rojava textbooks only once feature the name of its ideological leader, Öcalan, as an influential figure for a “martyred” fighter. Likewise, the YPJ flag appears only once and in partial view in Zanistên Civakî 4 behind the portrait of Arîn Mîrkan (ZC4). The findings of this research thus contradict some news reports which suggest that the new primary school curriculum in Rojava teaches “Öcalan philosophy” accompanied by “cheerful images” of him and “Rojava flags” (Yosif, Nelson, & Jamal, 2015). Frequent references to Kurdistan and the usage of Kurdistan maps prevail in the school textbooks in Rojava. Zanistên Civakî 5 states explicitly that Kurdistan is divided into four states and details the region's history, culture, geography, and economic resources. The Turkish textbooks incorporated relatively scarce reference to Turkey's geography, borders, or economy but, rather, focused on its history and culture.

Second, while the Turkish textbooks concentrate heavily on the “national struggle” during the war of independence, Rojava textbooks highlight their own ongoing struggle for freedom and democracy. Hence the references to the role “Kurdish women” play in their struggle and women's stature as the cornerstone of the family unit. Rojava school textbooks glorify the status of martyrs in this struggle, for both men and women, and depict their images, life stories, and struggles in communities, be they Arabs, Assyrians, and Kurds. Textbooks in both Turkey and Rojava tend to emphasise the martyrdom and extol it in a nationalist way. As Yenen (2019, p. 30) rightly argues, “cultures of martyrdom pushes conflicts towards grievance,” which then equates attempts at reconciliation attempts with betrayals. Martyrdom continues to be salient in Turkey, including on the “radical-revolutionary left and on the ultra-nationalist far-right,” as well as in Rojava.

Third, although textbooks in Turkey and Rojava emphasise either the Turks and Turkey or the Kurds and Kurdistan, the Turkish textbooks make no reference to other ethnic or religious groups in Turkey. Rojava textbooks do mention other linguistic, religious, and ethnic communities that live in the cantons, particularly Arabs and Assyrians, who also struggle collectively for democratic autonomy. Still, school textbooks in both Turkey and Rojava encompass the construction of a “we” feeling through the frequent use of the pronoun “our.” Van (2006), p. 124) describes the “us vs. them” distinction as “discursive structures and strategies” that create in-groups and out-groups. Reflections of this dichotomy have previously been analysed for school textbooks in Turkey (Babahan, 2014; Copeaux, 2002, 2002b; Meral, 2015). Showing the existence of similar tendencies in textbooks used in democratic confederalism is crucial for the purposes of this article.

Textbooks in Turkey continue to ignore the existence of the Kurdish identity, use hostile discourses against other national identities, which (like the Armenians and Greeks) were constituent parts of the Ottoman Empire, and still have a fixation on Atatürk and overuse symbols such as the Turkish flag or national anthem. The analysis of the school textbooks suggests the profound presence of a Turkish nationalist mentality and the active denial of identities that are neither Turkish nor Sunni.

Textbooks used in Rojava have a more emancipatory approach by utilising three languages in school instruction and not imposing national symbols such as flags, anthems, oaths, or portraits of the Kurdish political leaders, despite their existence. Despite scant reference to Öcalan, these books contain some discussions, such as the origins of the Kurds and the role of women and family in democratisation, that coincide with Öcalan's writings and thus with the overarching agenda of the Kurdish movement. Kurdistan is frequently referred to, but it is important to highlight that the textbooks do not use a militant narrative that questions the unity or integrity of the four countries across which Kurdistan stretches. Emphasis on the role of families, mothers, and women in the construction of a democratic society is prevalent within Rojava. Perhaps the main problem with the narratives in Rojava textbooks pertains to the glorification of martyrdom and even suicide bombing, which could be interpreted as militarisation at the primary school level. Textbooks in Rojava also merit criticism for deviating from its self-declared commitment to be a confederation of Kurds as well as other identities such as Arabs, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians, and Chechens, as Kurdishness does receive the bulk of emphasis over any other identity. This warrants further investigation through a comparative content analysis of books taught in Arabic and Syriac in Rojava.

Another aspect of this comparison worth discussing is that Turkey and Rojava possess drastically unequal educational resources. Rojava resides in an ongoing war zone in which daily survival is a common concern. Despite its teachers' commitment to educating students, “people are struggling to survive, and most regard education as having only secondary importance” (Knapp et al., 2016, p. 183). A war zone engenders challenging conditions for teachers to improve the learning environment and to source suitable educational materials. Knapp et al. (2016, p. 176–180) point out that “as soon as students learned how to read and write Kurdish and became familiar with the grammar, they began to teach it themselves” making “Kurdish language courses self-propagated.” They address the difficulties in terms of the proper translation of Arabic texts into Kurdish or the modification of longstanding “statist, hierarchical, patriarchal-sexist, and racist content and thinking (which) are hidden in the curriculum (and) taught to children.” Textbook translation is a time-consuming task, and the prevailing war conditions complicate the ability to update the curriculum and the content of these books in time. Another limitation is that intergovernmental organisations such as the United Nations Children's Fund have not recognised Rojava as a state actor, thus depriving the administration and region of the resources, exchange of knowledge, and cooperation that might improve such conditions (Drwish, 2017). In an interview he conducted in Kobane in 2014, Schmidinger (2018, p. 216) learned from a journalist in Rojava that they need the “civil support” that has been given to the Syrian opposition groups but not the Rojava movement, even though the democratic self-administration in Rojava “would certainly need the assistance of the EU.”

Finally, while a comparison of textbooks from Turkey and Rojava is informative, equating the educational structures and opportunities of the two administrations is, by no means, completely fair. Ultimately, Turkey is a country whose Republic was founded nearly a century ago, which has been involved in EU-ascension talks since 1999 and which has the second largest army in NATO. Rojava, on the other hand, remains a war zone, consisting of a stateless community struggling each day to build a new political model to maintain its existence in the world's “deadliest region” (Dudley, 2017) with no political support from other regional or global actors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Heartfelt thanks to Mehri Ghazanjani without whom I would not be able to conduct this research and to Darya Najim for translating Kurdish texts to English. Many thanks to Yasin Duman for double-checking the translations and his valuable comments. Finally, I would like to thank the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul and the Swedish Institute for funding this research.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul and Swedish Institute (Grant 21903/2017).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ENDNOTES

- 1 “Bomba seslerinin yani sira silah sesleri de geliyor. Daha cok taramali tufek gibi. Tak tak tak tak tak… Ogretmenler hizla cocuklari okul bahcesinden iceri almaya calisiyorlar. Simdi derse girdiler. Bombalar arasinda matematik, fen, tarih isleyecekler. Kendilerinin olmayan bir tarihi” (personal translation). Unless stated otherwise, all translations from Turkish are personal translations.

- 2 See Carrier (2018) on the concepts of nation, nationhood, and nationalism in textbook studies and Chisholm (2018) on the representations of class, race, and gender in school textbooks.

- 3 Previously called the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS) and often referred to as Rojava.

- 4 The Charter of the Social Contract in Rojava (https://ypginternational.blackblogs.org/2016/07/01/charter-of-the-social-contract-in-rojava/; accessed on July 25, 2018). The Social Contract of Rojava was later replaced by the Social Contract of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (http://frankfurt-kobane.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Social-Contract-of-the-Democratic-Federation-of-Northern-Syria.pdf; accessed on January 2, 2019).

- 5 For a recent discussion of the 40-year Turkey–PKK conflict, see Ünal (2016) and Parlar Dal(2016).

- 6 The Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Interior, and “PKK/KCK Terrorist Organisation's Extension in Syria PYD-YPG” (http://www.mia.gov.tr/pkkkck-terrorist-organisations-extension-in-syria-pyd-ypg; accessed July 17, 2019)

- 7 In the first years of their education, children are taught in their native languages and are then offered elective language courses (Aydin, 2014). In the fifth grade, students in Rojava begin taking English language courses.

- 8 For a recent report on the education policies of Turkey, see OECD (2018) Turkey: The Overview of the Education System. Accessed August 16, 2019 (http://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=TUR&treshold=10&topic=EO)

- 9 Darya Najim holds an MA in Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University, Sweden.

- 10 The aim of Knowledge of Life (also translated as Life Science) course “has been determined as the development of positive individual qualifications, in addition to children's acquisition of basic life skills, in the guideline named as Elementary Education 1st , 2nd and 3rd grades, Life Science Course Curriculum and Guideline, which is prepared by Ministry of National Education, Board of Education” (Peker, 2011).

- 11 Textbooks in Turkey were accepted as course books for five consecutive years beginning from the 2015–2016 academic year. Textbooks in Rojava do not have dates on them but were collected by Dr. Mehri Ghazanjani in the summer of 2017.

- 12 Covering the face implies the person is potentially in criminal activity.

- 13 Welat can also mean homeland.

- 14 In the early 2000s, Öcalan started using Mesopotamia as “the cradle of civilisation,” from which he claims to find “authentic and indigenous inspiration” (Casier, 2011, p. 427). Over the years, Mesopotamia was preferred as a regional name, in line with the idea of the withering of the state through democratic confederalism (Casier, 2011, p. 429).