Liver transplantation in patients with liver failure: Twenty years of experience from China

Handling editor: Alejandro Forner

Sunbin Ling and Guangjiang Jiang contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Liver transplantation (LT) is the only effective method of treating end-stage liver disease, such as various types of liver failure. China has the largest number of patients with hepatitis B virus-related disease, which is also the main cause of liver failure. From the first LT performed in 1977, and especially over the past two decades, LT has experienced rapid development as a result of continuous research and innovation in China. China performs the second-highest number of LTs every year worldwide, and the quality of LT continues to improve. Starting January 1, 2015, all donor's livers have been from deceased donors and familial donors. Thus, China entered into a new era of LT. However, LT is still a challenging procedure in China. In this review, we introduced the brief history of LT in China, the epidemiology, aetiology and clinical outcomes of LT for liver failure in China and summarized the experience of LT from Chinese LT surgeons and scholars. The future perspectives of LT were also discussed, and it is expected that China's LT research could be further integrated elsewhere in the world.

Lay Summary

This review introduced the past and current status of liver transplantation due to liver failure in China. We also discussed the future perspectives on improving the efficacy of liver transplantation for liver failure.

1 INTRODUCTION

Liver failure means that the liver is not working well enough to perform its functions, such as synthesis, detoxification, metabolism and biotransformation. The symptoms of liver failure include jaundice, coagulopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy and ascites. Based on patient medical history and disease onset and progression, liver failure can be divided into four categories: acute liver failure (ALF), subacute liver failure (SALF), acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and chronic liver failure (CLF).1 In China, the causes of liver failure mainly include infection with hepatitis viruses (mainly hepatitis B virus, HBV) and the use of alcohol and drugs.1 Liver transplantation (LT) is the only effective method of treating liver failure.1, 2 Over the past two decades, LT has experienced rapid development as a result of continuous research and innovation in China. This article is a review of the past and current status of LT due to liver failure in China.

2 BRIEF HISTORY OF LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN CHINA

In 1977, the first LT was performed in China. During the initial period, the indication for LT was mainly focused on advanced primary liver cancer, and the curative effect was poor. LT was stagnated in the 1980s due to poor cost-effectiveness.

In the 1990s, due to improvements in surgical technology, perioperative management and immunosuppressive therapy, LT regained its clinical application in China. During this second wave of LT, Professor Shusen Zheng was regarded as the initiator, who started the LT program in Zhejiang University in April 1993. Over the past two decades, LT has developed rapidly and has become an effective and routine surgical intervention in numerous regional medical centres in China. Moreover, LT is strictly regulated and monitored by National Health Commission. As of 2021, 109 centres have the authority to perform LT in the mainland of China. In total, 24 423 adult patients underwent LT in China from 2015 to 2020.

In 2005, the China Liver Transplant Registry (CLTR) database (http://www.cltr.org/) was established, which was later recognized by the National Health Commission in 2008 as the only national database to record almost all LT data occurring in the mainland of China. Specifically, the CLTR provides the annual reports of LT, including characteristics of liver transplant donors and recipients, surgical information, post-LT condition and survival analysis. The CLTR is dedicated to the scientific analysis and evaluation of LT, links all transplant centres, contracts with the government and promotes the clinical work and scientific studies of LT. The data from the CLTR provides the essential evidence for the development of the LT clinical guidelines in China.3, 4 In 2018, to further strengthen the medical quality and data management of LT in China, the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Liver Transplant was established as an official organization based on the CLTR.

Starting on September 1, 2013, all community-based donations of organs from deceased donors were coordinated through the China Organ Transplant Response System (COTRS, http://www.cot.org.cn), which is the sole official electronic organ allocation system in China.5 The allocation of organs outside of the COTRS is forbidden. With the developments that have occurred over the past 5 years, COTRS becomes more fair, efficient, scientific, transparent and appropriate for China's national conditions, which is an important guarantee for the development of LT.6 Furthermore, on December 4, 2014, Professor Jiefu Huang, the Director of the National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee (NODTC) of China, made a public announcement that China would stop using organs from prisoners executed by the state for transplantation, which took effect January 1, 2015.5, 7

The quantity and quality of LT have been improving progressively over the past two decades, because of the fruitful clinical studies and innovations. Some of the examples are listed. The establishment of the “Hangzhou criteria” and the new prognostic stratification system,8 which first included molecular biomarkers to the LT selection criteria of recipients with HCC and expanded the candidates.3 The proposed Chinese plan for the treatment of recurrent hepatitis B in post-LT patients.9 The creation of a new treatment for liver failure by combining an artificial liver supporting system (ALSS) with LT.

3 OVERVIEW OF LIVER TRANSPLANTATION FOR LIVER FAILURE IN CHINA

3.1 Epidemiology and aetiology

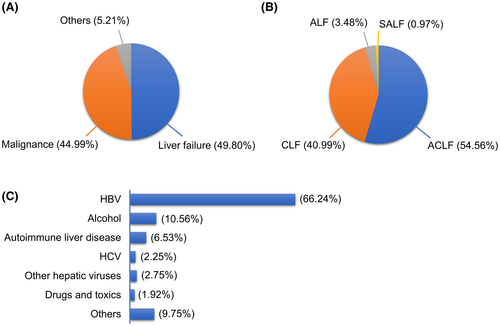

According to the CLTR data, among all adult transplant recipients from 2015 to 2020, recipients with malignant liver tumours accounted for approximately 44.99% and those with liver failure accounted for 49.80% (Figure 1A). China has heavy burdens of HBV-related cirrhosis and HCC, and the main indications for LT in China are HBV-related liver failure and malignancies.10 Among recipients with liver failure, ACLF and CLF patients accounted for 54.56% and 40.99%, respectively (Figure 1B). Approximately 80% of recipients with CLF accompanied serious complications, such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy and coagulation dysfunction. HBV infection was the most common cause of liver failure (66.24%), and alcoholic liver diseases and other causes, such as autoimmune liver disease and HCV infection, accounted for 10.56%, 6.53% and 2.25%, respectively (Figure 1C). Moreover, mixed causes of liver failure, especially approximately 30% of HBV infection patients are accompanied by alcoholic liver diseases. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (UNOS/OPTN) database, the top three factors precipitating LT in the United States are hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and alcoholic liver disease, which account for 33.37%, 17.38% and 17.20% of LTs, respectively, which is clearly different from the situation in China.11

Anti-HBV therapy is of great importance in China. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) should be administered during the anhepatic phase of the LT procedure. The combination of entecavir or tenofovir with low-dose HBIG is currently considered the best first-line regimen due to its reliable preventive effect against HBV recurrence.3

3.2 Timing of liver transplantation

The COTRS system allocates liver grafts based on medical urgency and the waiting time of patients on the list. For patients with liver failure, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score is an effective means of assessing disease severity and is the main basis for determining the priority of allocation. A MELD score of 15–40 points is the best indication for LT.12 Besides, LT candidates in Super-Urgent status, which means the life expectancy of patients who do not undergo LT is less than 7 days, have the highest priority of allocation.

For patients with ACLF, the Chronic Liver Failure Consortium ACLF (CLIF-C ACLF) score is better than the MELD score for predicting survival.13 The expert consensus in China recommends that priority for LT should be given to patients with grade 2–3 CLIF-C ACLF, and recommends that LT should be performed 3–7 days after the diagnosis of ACLF is made.14 In an European cohort, grade 2–3 ACLF patients undergoing LT in 3–7 days after diagnosis, achieved the 28 days and 180 days survival rates of 95.2% and 80.9%, respectively.15 In the United States, improvement of ACLF-3 at listing to a lower grade of ACLF at transplantation significantly enhances post-transplant survival,16 and other models have also been validated,17 which may have appropriate recommendations but need to be validated in China.

In China, HBV-related ACLF is the most common subtype of ACLF. A panel of experts from China has defined HBV-ACLF, known as the Chinese Group on the Study of Severe Hepatitis B-ACLF (COSSH-ACLF). HBV-ACLF occurs in patients with HBV-related chronic liver disease, which is often presented with different complications and has high short-term mortality.18 The COSSH-ACLF prognostic criteria, including the international normalized ratio (INR), age, total bilirubin and HBV-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, were superior to other criteria for the prediction of short-term mortality. The COSSH-ACLF criteria successfully identified approximately 20% more patients with HBV infection-related ACLF, thus being recommended to determine the need for LT in chronic HBV infection patients with cirrhosis or severe liver injury.18 Patients who fulfilled the COSSH-ACLF criteria had a transplant-free mortality rate of 51.1% to 72.0%. The COSSH-ACLF criteria could be recommended as recipient selection criteria in patients with chronic HBV infections. Recently, based on a recent prospective open cohort of the COSSH study (January 2017 to December 2018), a new prognostic score including six indicators was further established.19 This new prognostic score system is more feasible in clinical practice.

3.3 Outcomes in liver failure patients after liver transplantation

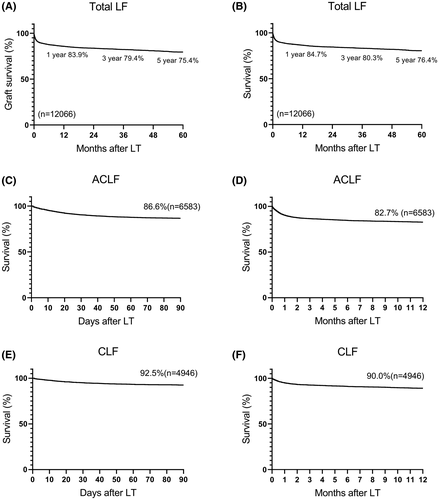

Based on the CLTR database, the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year graft survival of liver failure patients after LT were 83.9%, 79.4% and 75.4%, respectively, and patient survival was 84.7%, 80.3% and 76.4%, respectively (Figure 2A,B). The 90-day and 1-year survival rates of ACLF patients after LT were 86.6% and 82.7%, respectively (Figure 2C,D). The 1-year survival rate seems worse than those reported in the UNOS database (82.0% to 90.2%).16 The differences in the disease severity, etiologies, diagnostic methods, ethnicities and organ allocation systems may contribute to this discrepancy. Thus, further statistical analysis is needed to address the differences in the survival of recipients. Moreover, for CLF patients, the 90-day and 1-year survival rates after LT were 92.5% and 90.0%, respectively (Figure 2E,F).

4 FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

4.1 Expanding the donor pool for liver transplantation

As a result of the increase in the number of patients listed for LT and the shortage of available liver grafts, there is a need to increase the number of available organs; therefore, the use of many organs that were previously considered “unusable”, namely, “extended criteria donor” organs, such as ABO-incompatible grafts, liver grafts from elderly individuals, and steatotic liver grafts, began to be discussed.

ABO-incompatible LT is an effective way to save the lives of patients with end-stage liver disease in emergency situations. However, previous studies in China have found that although there is little difference in the complication rates after the transplantation of ABO-incompatible or ABO-compatible donor livers,20 the 1-, 3- and 5-year graft and patient survival rates of patients receiving ABO-incompatible donor livers are significantly lower than those of patients who received ABO-compatible donor livers.21 The transplantation of an ABO-incompatible donor liver was an independent prognostic factor affecting overall survival after living donor liver transplantation22 and might be related to the extrahepatic recurrence of liver cancer after LT. Therefore, further research on the use of ABO-incompatible donor liver grafts is still needed.23 In recent years, an increasing number of studies have reported the use of donor livers from elderly individuals as a method of increasing the donor pool. Some studies have shown that donor age is related to a decrease in overall survival but not tumour recurrence after transplantation in recipients with HCC.24 Advanced age is not a contraindication for liver donation.25 A study including 148 recipients from our group found that shortening cold ischemia time will reduce the incidence of early allograft dysfunction (EAD) to approximately 25% in recipients with elderly donors (age of donors ≥60).26 However, controversy remains regarding the adverse effects on graft function and long-term patient survival.27-29 Thus, the use of a donor liver from an elderly individual can be a prudent choice, but high-quality research is still needed to determine the safety thresholds for donor age and the age difference between the donor and recipient to ensure satisfactory results after transplantation. There are also many controversies regarding the use of steatotic liver transplants in clinical practice. The use of steatotic liver transplants may increase complications such as new-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT) and poor postoperative survival.30, 31 Other studies have shown that the use of livers with moderate and severe steatosis is associated with poor short-term outcomes but has relatively little impact on the long-term outcomes, and an individual with moderate or severe steatosis might be a suitable donor if there is strict control over the transplantation conditions.32, 33 Studies have suggested that the threshold for macrovesicular steatosis in the donor liver can be safely extended to 30%–60% to expand the pool of liver donors.34 Besides, EAD is associated with poor patient survival.35 Our group started predicting EAD in LT recipients with clinical models36 or biomarkers.37, 38

China has fully entered the era of donation after citizen death. However, due to the increase in biliary complications, ischemic cholangiopathy, graft loss and mortality39 compared to donation after brain death (DBD), the utility of donation after cardiac death (DCD) grafts remains controversial. According to the CLTR data, in China, during the 2018–2020 period, DCD was the source of livers in about 40% of LT. Our group recently found that longer cold ischemia time, older donor age and a higher MELD score of recipients predict a higher occurrence of EAD in patients after DCD LT.36 With the development of organ storage techniques, such as normothermic machine perfusion (NMP)40, 41 and hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE),42 DCD and extended criteria donor livers are expected to be more useful, and less EAD may occur, which is also an important research direction.

4.2 Perioperative management

Patients with liver failure often have multiple organ dysfunctions, such as coagulation dysfunction, respiratory failure, cerebral oedema, internal environment disorders and hepatorenal syndrome, which further increase the risk of needing LT. In particular, for ACLF patients, the high postoperative complication rate and fatality rate are also challenges in the treatment of LT. China has achieved a breakthrough in the perioperative management of patients with liver failure by creating a new program combining ALSS with LT for the treatment of end-stage liver disease.43-45 The program advocates for the implementation of ALSS before transplantation to significantly reduce the MELD score and enable a longer wait for a donor liver. This program has significantly improved the survival rate of patients with liver failure and addressed the global problem of the high mortality rate in patients with liver failure with high MELD scores. The ALSS may serve as a bridge to extend the time window in which LT can be performed. However, the timing of LT in patients with ACLF, the prevention and control of perioperative infections, and the maintenance of nutrition and organ function are challenges that need to be deeply explored.

4.3 Long-term management after LT

Owing to the occurrence of some long-term complications, such as metabolic disease,46 cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, the 10-year survival rate after LT is approximately 60.0%.47 After LT, the use of immunosuppressive agents often leads to complications such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity and renal damage. In addition, for HCC-related LT, transplant oncology guides the direction of development.48 Moreover, with the changes in the spectrum of diseases and the improvement of general living standards, the perspective on health and medical models have changed. To evaluate the efficacy of LT, it is important to consider not only objective indicators, such as the cure rate, mortality and survival duration but also the long-term quality of life of LT recipients. Therefore, optimizing a better plan for the induction of immune tolerance and constructing an intelligent management model are important aspects of the long-term management of LT recipients in China.

5 CONCLUSION

In summary, over the past two decades, both LT quantity and quality are improved rapidly in China. Liver failure accounted for 49.80% causes among all adult transplant recipients. Among recipients with liver failure, ACLF and CLF patients accounted for 54.56% and 40.99%, respectively. MELD score is an effective means of assessing liver failure severity and is the main basis for determining the priority of donor liver allocation. The COSSH-ACLF criteria could be recommended as recipient selection criteria in ACLF patients caused by chronic HBV infections. Development of the donor pool expansion, perioperative management and long-term management after LT may further improve the efficacy of LT for liver failure. It is expected that China's LT research could be further integrated elsewhere in the world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express thanks to Dr. Jimin Liu ([email protected]) from McMaster University of Canada for her help in language revision, and to Dr. Mengfan Yang ([email protected]), Dr. Zuyuan Lin ([email protected]), Dr. Wenhui Zhang ([email protected]) and Mr. Zhisheng Zhou ([email protected]) form our group for their help in the revision phase. This work was supported in part by funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1100500) to Xiao Xu and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902407) to Sunbin Ling.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Funding information

This work was supported in part by funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1100500) to Xiao Xu and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902407) to Sunbin Ling.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Not applicable.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Not applicable.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM ANOTHER SOURCE

Not applicable.