Treatment and the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia

Handling Editor: Luca Valenti

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common type of malignant tumour in Asia. Treatment is decided according to the staging system with information on tumour burden and liver function. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system is the most commonly used staging system for the selection of appropriate treatments worldwide, and although it is highly evidenced-base, it has very strict guidelines for treatment. In Asian countries, many efforts have been made to expand the indications of each treatment and combination therapies as well as alternative therapies for better outcomes. The guidelines in Asia are less evidence-based than those in Western countries. More aggressive treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma are generally employed in the guidelines of Asian countries. Surgical resection is frequently employed for selected hepatocellular carcinoma patients with the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages B and C, and combination therapies are sometimes selected, which are contrary to the recommendations of American and European association for the study of the liver guidelines. Recently, a paradigm shift in treatments for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma has occurred with molecular targeted agents, antibodies and immune checkpoint inhibitors in Asia. Atezolizumab+bevacizumab therapy has become the first-line systemic treatment ineligible for radical treatment or transarterial chemoembolization in Asian countries. The overall survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma varies substantially across Asia. Taiwan and Japan have the best clinical outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. Intensive surveillance programmes and the development of radical and non-radical treatments are indispensable for the improvement of prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Abbreviations

-

- AASLD

-

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

-

- APASL

-

- Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver

-

- ASIR

-

- age-standardized incidence rates

-

- ASMR

-

- age-standardized mortality rates

-

- BCLC

-

- Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

-

- CNLC

-

- China Liver Cancer

-

- DEB

-

- drug-eluting beads

-

- EASL

-

- European Association for the Study of the Liver

-

- EBRT

-

- external beam radiotherapy

-

- ECOG

-

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

-

- ESMO

-

- European Society for Medical Oncology

-

- HAIC

-

- hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HKLC

-

- Hong Kong Liver Cancer

-

- INASL

-

- Indian National Association for the Study of Liver

-

- JSH

-

- Japan Society of Hepatology

-

- KLCSG

-

- Korean Liver Cancer Association

-

- LDLT

-

- living donor liver transplantation

-

- LR

-

- liver resection

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MTAs

-

- molecular targeted agents

-

- NCC

-

- National Cancer Center

-

- PD-1

-

- programmed cell death-1

-

- PS

-

- performance status

-

- PVTT

-

- portal vein tumour thrombus

-

- RCTs

-

- randomized controlled trials

-

- RFA

-

- radiofrequency ablation

-

- RT

-

- radiation therapy

-

- SBRT

-

- stereotactic body radiation therapy

-

- TARE

-

- transarterial radioembolization

-

- TLCA

-

- Taiwan Liver Cancer Association

-

- UCSF

-

- University of California, San Francisco

-

- UICC

-

- Union for International Cancer Control

Key points

- We showed the characteristics of treatment guidelines in Asian countries comparing with those in Western countries.

- We also summarized the current topics of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatment and its therapeutic effects in Asian countries.

- Additionally, we discuss the future direction of HCC management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death and ranks as the sixth most common neoplasm, with 841 080 diagnosed cases and 781 631 deaths globally in 2018.1, 2 These numbers are gradually increasing worldwide. The estimated incidence of liver cancer will be more than 1 million by 2025.3 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for approximately 75%-85% of all primary liver cancers. It is estimated that 72% of cases occur in Asia (more than 50% in China), 10% in Europe, 7.8% in Africa, 5.1% in North America, 4.6% in Latin America and 0.5% in Oceania.4 In Asia, the highest age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) per 100 000 is seen in Eastern Asia (17.7), with Mongolia (93.4) having the highest ASIR, followed by East Asia (17.7) and Southeast Asia (13.3). The lowest ASIR was observed in South-Central Asia (2.5), followed by Western Asia. (4.0).5 HCC is a major health problem in Asian countries. HCC has two unique characteristics. First, it usually develops from a chronically damaged liver. Hepatitis B virus infection is the main cause of HCC in Asia. Japan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Pakistan are exceptions because of the high prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in these regions.6 The other characteristic of HCC is that it repeatedly shows a multicentric recurrence after curative treatment. Therefore, in clinical practice, most patients with HCC require subsequent treatment for recurring HCC. Appropriate subsequent treatment is as important as the initial treatment for improving patient survival in HCC.

Currently, surgical resection, liver transplantation (LT) and locoregional treatments, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), are recommended as curative treatments for HCC. However, only one-third of HCC patients are possible candidates for these curative treatments, and the remaining 60%-70% of patients receive non-curative treatments such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), molecular targeted agents (MTAs), monoclonal antibodies or immune checkpoint inhibitors as initial therapy.7 Prognostic assessment and treatment allocation are crucial steps in the management of patients with HCC.7 Since most cases of HCC are associated with chronic liver diseases, a staging system with the information on tumour burden and liver function reserve has been proposed.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system has been extensively validated and is most commonly used worldwide.8, 9 However, the BCLC staging system has strict guidelines for treatment. Many hepatologists in Asian countries have made efforts to adopt the principles of the BCLC staging system; in contrast, they are also independently making efforts to expand the indications of each treatment and to combination therapies as well as alternative therapies for better outcomes.10

In this review, we summarized the current topics of HCC treatment and its therapeutic effects in Asian countries. Additionally, we discuss the future management of HCC in Asia.

2 GUIDELINES ON THE TREATMENT OF HCC

2.1 BCLC staging system

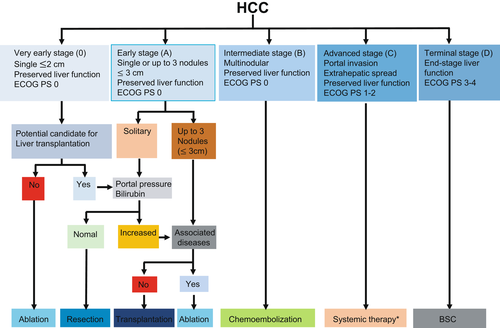

In 1999, the BCLC staging system was first introduced.8 The latest BCLC staging system consists of five stages (0, very early stage; A, early stage; B, intermediate stage; C, advanced stage; D, terminal stage)9 (Figure 1). Among the five stages, BCLC stage 0 (single nodule<2 cm in diameter, Child-Pugh class A, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [ECOG PS] 0) or A (Single or 2-3 nodules <3 cm in diameter, Child-Pugh class A or B, PS0) HCC is a candidate for curative treatment (ie hepatic resection, RFA and transplantation). In these stages, the estimated survival time is 5 years or more. BCLC stage B (nodules out of Milan criteria without vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis, Child-Pugh class A or B, ECOG PS0) is a candidate for TACE. The estimated survival time for HCC patients with BCLC stage B is more than 2.5 years. BCLC stage C (advanced HCC with vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis, Child-Pugh class A or B, ECOG PS 1-2). Today, these patients are usually treated with systemic therapy with MTAs and atezolizumab+bevacizumab. The estimated survival time is >1 year. HCC patients with BCLC stage D have a poor liver function (Child-Pugh class C) and severe cancer-related symptoms (PS 3-4). The estimated survival time for these patients is only 3 months.9 The BCLC staging system is endorsed by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)11 and is tied to treatment guidelines. Hepatobiliary Neoplasia Special Interest Group of AASLD organized a single topic conference in Atlanta in 2019 to address new guideline adapted to the progress of systemic therapies. The updated modified BCLC staging system was modified from EASL guidelines considering effective therapies in advanced stage.12 In modified BCLC staging system, atezolizumab+bevacizumab was approved as a new first-line treatment for advanced and intermediate stages.

The BCLC staging system is the most widely used staging system in the Western hemisphere and is often used to determine eligibility in clinical trials. In East Asia, however, it is routinely used only in Taiwan.13

2.2 Guidelines in Asian countries

The BCLC staging system was derived from a predominantly Western population. The staging systems derived from Asian populations seemed to be the best prognostic model when tested in cohorts from Asian countries.14-16 Additionally, the BCLC staging system has strict guidelines for treatment. Furthermore, no combination therapy was recommended according to the BCLC algorithm. Hepatologists in Asia have developed their own guidelines to adapt to the situation and treatment strategy for HCC in each Asian country. In Asian countries, surgical resection is frequently employed for selected HCC patients with BCLC stage B and C, in contrast to the recommendations of the AASLD and EASL guidelines (Table 1).

| BCLC | 0/A | B | C | D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLCSG | LR (nodules ≤2) | TACE (EBRT as alternative) | TACE±EBRT | |||

| RFA | LR ("nodules "≤"2") | LR (single nodule, MVI(+)) | ||||

| EBRT (except for multiple nodules with MVI) | ||||||

| OLT | OLT (within Milan's) | MKI | ||||

| TACE/TARE, EBRT | EBRT (single nodule) | HAIC (MKI failed or not available) | ||||

| HKLCS | LR/OLT/Ablation | LR/OLT/Ablation (≤5 cm & ≤3 nodules) | LR (≤ 5 cm, VP4(-), EHM(-), CP A) | OLT (within Milan's) | ||

| LR (≤5 cm, ≥4 nodules, CP A or >5 cm, ≤3 nodules, CP A) | TACE (≤ "5 cm, VP4(−), EHM(−), CP " B or ≤5 cm, ≥4 nodules, "VP4(−), EHM(−), " or >5 cm, >3 nodules, "VP4(−), EHM(−)," or diffuse, "VP4(−), EHM(−)" ) | BSC (others) | ||||

| TACE (≤5 cm, ≥4 nodules, CP B or >5 cm, ≤3 nodules, CP B or >5 cm, >3 nodules or diffuse) | Systemic ("VP4(−), EHM(−))" | |||||

| China | LR/Ablation | LR/Ablation (> 3 cm, ≤ 3 nodules) | LR (MVI) | |||

| OLT(within UCSF) | OLT (within UCSF) | TACE (MVI) | BSC | |||

| TACE (2-3 nodules, ≤ 3 cm) | TACE (> 3 cm or ≥4 nodules) | EBRT (MVI) | ||||

| EBRT | * Systemic (> 3 cm or ≥4 nodules) | * Systemic (MVI) | ||||

| JSH | LR/Ablation | LR (≤ 3 nodules) | HAIC/Systemic (≥ 4 nodules) | LR (EHM(-)) | OLT (within Milan's or 5-5-500) | BSC (Others) |

| TACE | Systemic | |||||

| TLCA | LR | LR/TACE/TARE | LR/** Systemic (MVI) | OLT (within Milan's) | BSC (Others) | |

| Ablation | Ablation (single, <5 cm or 2-3 nodules) | TACE+EBRT, TARE or HAIC (MVI) | ||||

| TACE | EBRT (2-3 nodules) | |||||

| EBRT | **Systemic/Ablation/TARE/EBRT (TACE refractory) | **Systemic ±LR/TACE/TARE/EBRT (EHM) | ||||

Note

- Systemic; MKI, atezolizumab+bevacizumab; * Systemic; MKI, FOLFOX, PD-1 inhibitors; **Systemic; MKI, atezolizumab+bevacizumab, other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

- Abbreviations: BCLC, Barcelona Liver Cancer; BSC, best supportive care; CP A, Child-Pugh score A; CP B, Child-Pugh score B; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; EHM, extrahepatic metastases; EVM, extrahepatic vascular metastasis; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HKLCS, Hong Kong Liver Cancer Staging system; JSH, Japan Society of Hepatology; KLCSG, Korean Liver Cancer Study Group; LR, liver resection; MKI, multi-kinase inhibitor; MVI, macrovascular invasion; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TARE, transarterial radioembolization; TLCA, Taiwan Liver Cancer Association; Vp 4, main portal vein tumour thrombosis.

2.2.1 Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system

The Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) staging system was developed from a cohort of 3856 HCC patients with predominantly viral aetiology, particularly hepatitis B.17 The HKLC staging system is arguably more aggressive in its treatment recommendations, assigning patients with intermediate stage tumours (eg HKLC stage IIb) to curative treatment, whereas these patients would have been assigned to palliative treatment under the BCLC staging system.17 The HKLC staging system classifies patients with HCC into five stages with nine substages that have distinct median survival times based on differences in the extent of tumour, presence of vascular invasion, Child-Pugh stage and ECOG PS. Several studies have shown that the HKLC staging system can accurately stratify patients with HCC into different prognostic groups.18-20 Overall, the study performance of the HKLC staging system is promising, but further validation in prospective studies is warranted.

2.2.2 China Liver Cancer staging system

Compared to the BCLC staging system, the China Liver Cancer (CNLC) staging system employs resection, transplantation and TACE for more progressed HCC.21, 22 The CNLC staging system suggests resection in patients with Ia, Ib and IIa and selected patients with IIb and IIIa HCC, including multinodular HCC and locally advanced HCC with portal vein tumour thrombus (PVTT). Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has been adopted as an alternative to RFA. Ablation in combination with TACE has been proposed for selective inoperative solitary or multiple HCCs with a diameter of 3-7 cm according to Chinese guidelines.23 The CNLC staging system extended the indications for TACE for CNLC IIb and IIIa and selected IIIb HCC cases. TACE in combination with MTAs is not recommended by the EASL and AASLD.24-26 However, TACE with MTAs or immunotherapy has been advocated in the latest Chinese guidelines. In Western countries, TACE is considered to be a contraindication for HCC with macrovascular invasion, while the CNLC staging system recommends TACE or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) alone or in combination with other therapies for patients with PVTT, even at the main trunk.27 In China, MTAs and immune checkpoint inhibitors are available for treating advanced HCC. FOLFOX4 chemotherapy is also recommended as an option for advanced HCC in China.28 In 2019, traditional Chinese medicine became available for the treatment of advanced HCC.

2.2.3 Indian National Association for the Study of Liver staging system

The Indian National Association for the Study of Liver (INASL) modified the BCLC staging system. One of the most important modifications of the BCLC staging system proposed was regarding end-stage cirrhosis. According to the INASL staging system, patients with end-stage liver cirrhosis with heavily impaired liver function (Child-Pugh class C) but with tumour size within the Milan criteria and PS ≤ 2 should be considered for LT.29

2.2.4 Consensus guidelines of the Taiwan Liver Cancer Association

The Taiwan Liver Cancer Association (TLCA) employs resection, local ablation, TACE and radiation therapy (RT), including transarterial radioembolization (TARE) with Y90 for HCC with less than three nodules. Systemic therapy is recommended for HCC refractory TACE. For HCC with vascular invasion, resection, systemic therapy with sorafenib or lenvatinib as the first-line therapy or TACE with RT, TARE or HAIC is recommended. For HCC with extrahepatic metastasis, systemic therapy with or without RT/TACE, TARE or resection is employed. Regorafenib, cabozantinib and ramucirumab (when alpha-fetoprotein [AFP] ≧ 400 ng/mL) are selected as second or third-line therapy. Immunotherapy, such as nivolumab±ipilimumab and pembrolizumab, can be considered for HCC patients who are intolerant to or have progressed under approved MTAs. Atezolizumab+bevacizumab could be used in patients with HCC who have not received prior systemic therapy.30

2.2.5 Korean Liver Cancer Association-National Cancer Center practice guidelines

These guidelines provide the best and alternative treatments according to the modified Union for International Cancer Control staging.31 Hepatic resection is the first-line treatment for patients with intrahepatic single-nodular HCC. It can be considered for patients with three or fewer intrahepatic tumours with vascular invasion.

Liver transplantation is the first-line treatment for patients within the Milan criteria. Expanded indications for LT can be considered in limited HCC cases beyond the Milan criteria without definitive vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread if other effective treatment options are not applicable.

Radiofrequency ablation has an equivalent survival rate, a higher local tumour recurrence rate and a lower complication rate than hepatic resection in patients with a single nodular HCC less than 3 cm in diameter.

Conventional TACE (cTACE) is recommended for HCC patients without major vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread who are ineligible for surgical resection, LT or RFA. TARE can be considered as an alternative treatment to TACE.

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) can be considered for HCC patients ineligible for surgical resection, LT, other local modalities or TACE. It can be performed for HCC patients with PVTT if their liver function is Child-Pugh class A or B7 and the irradiated total liver volume receiving ≤30 Gy is ≥40%. It can also be used to alleviate symptoms caused by metastases.

Molecular targeted agents are recommended for HCC with vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis. Immune checkpoint inhibitors could be used for progressive HCC after MTAs or for patients intolerant to MTAs. Cytotoxic chemotherapy or HAIC can be considered for patients treated with MTAs or immune checkpoint inhibitors. HAIC may be considered for HCC patients with vascular invasion.

2.2.6 Clinical practice guidelines for HCC: The Japan Society of Hepatology

The guidelines of the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) were updated in 2021 and will be published before long. Hepatic resection can be considered for patients with three or fewer intrahepatic tumours. For selected HCC patients with vascular invasion, hepatic resection may be considered.

Radiofrequency ablation should be performed for patients with HCC, generally for Child-Pugh class A or B patients with three or fewer tumours, each 3 cm or less in diameter. LT can be generally considered for Child-Pugh class C patients with HCC within the Milan criteria or 5-5-500 criteria. TACE is recommended for HCC patients with more than four tumours. TACE may be considered for selected HCC patients with vascular invasion. HAIC may be considered for HCC patients with multiple nodules or vascular invasion who are not eligible for hepatic resection, transplantation, locoregional therapy and TACE. Systemic chemotherapy applies to HCC patients with Child-Pugh class A who are not candidates for radical treatments or TACE. Atezolizumab+bevacizumab is a first-line systemic treatment. Sorafenib and lenvatinib are considered for patients with HCC ineligible for atezolizumab+bevacizumab. EBRT can be considered for HCC patients with <3 tumours and tumours less than 5 cm in diameter who are not candidates for hepatic resection or locoregional therapy. Proton or carbon ion beams may be considered for HCC patients ineligible for hepatic resection or locoregional therapy. EBRT is also recommended for symptomatic bone or brain metastases.

2.2.7 Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver HCC guidelines

The Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) guidelines recommend that liver resection is a first-line curative treatment for HCC among Child-Pugh class A patients when resectability is confirmed.32 LT provides the best curative treatment for all HCC patients from an oncological point of view and is recommended as a first-line treatment for HCC among Child-Pugh class B and C patients if the liver graft is available. Percutaneous ablation therapies including RFA should be performed for patients with HCC, generally for Child-Pugh class A or B patients with three or fewer tumours, each 3 cm or less in diameter. RFA is a first-line treatment for HCC ≤ 2 cm in diameter and is also an acceptable alternative to resection for HCC ≤ 3 cm in diameter. TACE is recommended as a first-line treatment for HCC with unresectable, large/multifocal nodules without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. TARE may be used as an alternative locoregional treatment for unresectable HCC. Although EBRT and proton or carbon ion beam are reasonable options for HCC in which other local therapies have failed, EBRT has not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with HCC. However, radiotherapy may be considered for symptomatic bone metastases. MTAs are recommended as the first-line treatment for advanced-stage patients (macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis) who are not suitable for locoregional therapy and those with Child-Pugh class A.

2.2.8 The European Society for Medical Oncology Asia consensus guidelines

The aim was to adapt the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2018 guidelines to consider both ethnic and geographic differences in practice associated with the treatment of HCC in Asian patients.33 The guidelines represent the consensus reached by experts in the treatment of intermediate and advanced/relapsed HCC representing the oncology societies of Taiwan, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. The consensus guidelines accept that cTACE is the standard of care for patients with BCLC B HCC, although using drug-eluting bead (DEB)-TACE is an option to minimize the systemic side effects of chemotherapy. TARE can be used as an alternative to TACE as first-line therapy for patients with intermediate or advanced-stage HCC without extrahepatic disease.

Molecular targeted agents are the standard of care for patients with advanced HCC. However, based on low-level clinical evidence, cytotoxic systemic chemotherapy such as FOLFOX may be used in selected patients in the absence of the availability of MTAs.

Immunotherapy with nivolumab can be considered in patients who are intolerant to or have progressed under approved MTAs. Locoregional treatment (TACE, TARE, Liver resection and HAIC) for advanced, non-metastatic HCC with macrovascular invasion, and TACE and HAIC for metastatic HCC have shown benefits in some Asian studies and may be considered in selected patients.

3 THERAPEUTIC EFFICACY OF HCC IN ASIAN COUNTRIES

3.1 Overview

The overall survival (OS) of patients with HCC varies substantially across the world.34 Taiwan and Japan have the best clinical outcomes for patients. Probably owing to nationwide intensive surveillance programmes, more than 70% of HCCs diagnosed at major medical centres in both countries are detected at BCLC stage 0 and A and are eligible for curative therapies.35 Estimated median survival time of BCLC stage 0 and A is more than 5 years.9 In contrast, HCC outcomes in Korea, China, North America and Europe are not as good as those in Taiwan or Japan, as ≥60% of patients in these countries present with BCLC stage B or C.35 Estimated median survival time of BCLC stage B and C is more than 2.5 years and more than 10 months respectively.9

3.2 Treatment outcome in each therapy

3.2.1 Radical treatment

Hepatic resection

Western guidelines have restricted resection to those with a single tumour (regardless of size), with well-preserved liver function. Analysis of data from a large prospective registry found that the majority (>60%) of hepatic resections were performed in Asian patients who did not meet the criteria of Western guidelines.36 A multicentre study in Korea showed that liver resection provides a survival benefit compared with nonsurgical treatment for patients with potentially resectable BCLC stage B HCC.37 The recurrence of HCC after hepatic resection remains a major obstacle, with recurrence rates as high as 70% at 5 years, even in patients with a single tumour ≤2cm.38

The 5-year OS rates and disease-free survival rates are 46%-69.5% and 23%-56.3% respectively. 80%-95% of postoperative recurrences are intrahepatic.39 Prognosis after hepatic resection is determined by the number and size of tumours, vascular invasion and AFP levels.40-42 Five-year survival rates are >50% after the resection of solitary tumours, whereas rates of 20%-30% have been reported for three or more nodules.40-42 With respect to tumour size, 5-year survival rates for patients with HCCs <2, 2-5 and >5 cm are 66%, 52% and 37% respectively.40-42 However, in selected cases with proper hepatic function, large single HCCs can be surgically removed with favourable long-term survival outcomes.41

A recent meta-analysis performed by Xu et al showed that the 3-and, 5-year overall and disease-free survival rates were significantly higher in the resection group than in the RFA group. However, complications were significantly fewer and hospital stay was significantly shorter in the RFA group than in the resection group. In subgroup analyses, for HCCs ≤ 3 cm, the overall and disease-free survival rates in the resection group were also significantly higher than those in the RFA group, whereas there were no significant differences between the two groups for HCC ≤ 2 cm.43

In a consensus report of experts from Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, Japan and Korea, it was agreed that surgery provided a significant benefit for patients with intermediate or advanced HCC, in patients with a favourable functional liver reserve.44 In addition, in a recent Korean meta-analysis study comparing hepatectomy to chemoembolization, the 5-year survival rates for BCLC stage B and stage C HCC patients who underwent primary hepatectomy were significantly better than those for patients who received TACE.45 Several guidelines for multidisciplinary treatments for HCC in the Asia-Pacific region, including China, Hong Kong and Japan have been updated to identify surgical treatment as a feasible option for selected patients with HCC and PVTT.46 To prolong OS of HCC patients, it is important not to overlook the patients applicable to radical treatment such as surgical resection, RFA and RT in patients with BCLC stage B and C.

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation is the most definitive treatment option for HCC, as it removes not only the tumour but also the unhealthy liver, which has limited functional capacity and a tendency to develop additional metachronous HCCs within the cirrhotic tissue.34 The outcomes have been excellent, with 5- and 10-year survival rates of 70% and 50%, respectively, and recurrence rates of 10%-15% at 5 years.

In India, the Milan criteria remain the gold standard for the selection of patients with HCC in a deceased donor LT setting. The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) criteria have been also validated in several studies and yielded similar outcomes.47 In Taiwan and Hong Kong, the UCSF criteria48 were adopted. In China, the Hangzhou or Chengdu criteria are used with satisfactory outcomes.49 In Korea, the UCSF or Milan criteria are used, but living donor LT (LDLT) can be offered for any HCC without distant metastasis under national insurance coverage.

In Western countries,50 consequently, LT can be offered for those with Child-Pugh class A, as shown in the BCLC algorithm, if they satisfy the Milan criteria.51 In contrast, in Asian countries, where liver grafts are extremely scarce, LT is recommended for HCC patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis as well as in those with other diseases. LDLT is much more commonly performed in Asia.10

In Korea, at Samsung Medical Center, patient selection according to tumour size < 5 cm and AFP < 400 ng/ml without limitation of the tumour number expanded patient selection; 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates are reported to be 92.2%, 82.6% and 79.9% respectively.52 LT is the first-line treatment for patients within the Milan criteria who are not indicated for resection.31 The Kyoto group reported a 5-year survival rate of 82% in their cohort of 147 patients within their expanded criteria, whereas Mazzaferro et al reported a 5-year survival of 71.2% in 283 patients who met their up-to-seven criteria.53 In Asia, several independent criteria have also been proposed, expanding indications without significantly increasing the risk of HCC recurrence.54-59 The 5-year survival rate was as high as 80% after transplantation using these criteria.

Ablation

Percutaneous local ablation is a potentially curative treatment for patients with early-stage HCC. Image-guided percutaneous ablation therapies include ethanol injection, microwave ablation, RFA and others.

Based on a meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the most recent AASLD guidelines recommend that adults with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis and resectable small tumours should undergo resection rather than ablation.60-63 However, in Thailand, RFA is a major choice of curative treatment for patients who are not eligible to undergo surgical resection or LT. A recent study of RFA by Siriapisith et al showed that the local response rate in RFA was 97.3%.64 INASL recommends that in cirrhotic patients, with resectable solitary HCCs ≤ 2 cm (BCLC-0), RFA should be offered as the first-line treatment option, and the clinical outcome of RFA is comparable to that of liver resection in India.47 Three RCTs from China and Hong Kong, including a recently published study, showed no significant difference in survival rates between the two treatments.62, 63, 65 In Japan, a multicentre RCT to evaluate the efficacy of surgery versus RFA for small HCCs (Surgical resection vs Radiofrequency Ablation trial) showed the equivalent progression-free survival and OS of RFA and surgical resection.66

Radiofrequency ablation+transarterial chemoembolization

A meta-analysis of five RCTs in Korea, Japan and China showed significantly improved survival and better tumour response in patients receiving TACE+RFA compared with patients receiving TACE alone.67 Collectively, the available data suggest that RFA plus TACE provides better outcomes than RFA alone and may be as efficacious as surgical resection for medium-sized HCCs.10 The benefits of the combination therapy could be attributed to the avoidance of the heat sink effect and the subsequent increase in the size of the thermal coagulation zone.10 A consensus is needed for routine recommendation in practice guidelines.

Radiation (EBRT)

Recent technical advances ensure that high doses of radiation will be precisely delivered to the target in the liver while sparing the normal tissue.68 As a result, EBRT has been increasingly utilized, and practice guidelines for EBRT in HCC have been presented, especially in Asian countries.69, 70 The AASLD guidelines in 2018 were updated to include SBRT as an alternative to ablation. In a retrospective analysis with propensity score matching, EBRT was associated with a lower cumulative local recurrence rate; the 2-year cumulative local recurrence rates were 16.4% and 31.1% in the EBRT and RFA groups respectively. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that the treatment modality was attributed to local control, favouring EBRT.71 EBRT provides better local control than RFA, with comparable toxicities. Studies from Japan and China also reported the efficacy of radiotherapy for HCC with PVTT, and OS was significantly better in patients receiving radiotherapy than in patients receiving sorafenib (10.9 and 4.8 months respectively; P = .025) or undergoing surgery (12.3 and 10.3 months respectively; P = .029).72, 73 A retrospective study of proton beam therapy in 162 surgically unresectable patients reported a local control rate of 89% and an OS rate of 23.5% at 5 years.74 Proton beam therapy showed a good response rate even for large tumours (>10 cm) and HCCs with main portal tumour thrombosis.75, 76

3.2.2 Non-radical treatments

Transarterial chemoembolization

The TACE technique was first developed and reported by Yamada in 1978.77 TACE has been shown to improve OS in patients with non-resectable HCC in RCTs performed in Europe and Asia.78, 79 TACE is recommended as the standard of care for the treatment of lesions classified as intermediate stage according to the BCLC staging system. In Asia, where TACE is performed with a superselective technique, significant deterioration of hepatic function after TACE was rare.80-82

A “six-and-twelve” scoring system, presented as the largest tumour diameter (cm) plus tumour number, has proven to be an easy-to-use tool to stratify BCLC A/B candidates for TACE and predict individual survival with favourable performance and discrimination in China.83 The score identified three prognostic strata (≤6, >6 but ≤12 and >12), presenting significantly different median survival rates of 49.1, 32.0 and 15.8 months respectively. From a large multicentre cohort of 1604 patients, the six-and-twelve score is the first prognostic model for stratifying recommended TACE candidates.84 In Thailand, TACE is the most common treatment for advanced-stage HCC.5, 85-87 The median survival of patients with HCC after TACE treatment is 6.3-11.5 months. A prospective multicentre registry including 152 Korean patients showed complete remission and objective response rates of 40.1% and 91.4% at 1 month, and 43.0% and 55.4% at 6 months.88 DEB-TACE has similar long-term survival, less post-embolization syndrome and shorter hospital stay than cTACE. In a retrospective cohort study, Shimose, et al recommended the choice of DEB-TCE for HCC patients with Child-Pugh class B because of the high incidence of arterio-portal shunt formation in patients with Child-Pugh class A.89

The Asia-Pacific Primary Liver Cancer Expert Consensus meeting recommended superselective cTACE as the first choice of treatment in patients eligible for curative TACE, whereas in patients who are not eligible, systemic therapy is recommended as the first choice of treatment. Tumour response as per the modified RECIST criteria predicts longer OS in patients receiving TACE, especially initial CR, which can predict a longer survival benefit. Another important statement is that TACE should not be continued in patients who develop TACE failure or refractoriness to preserve liver function.90 The good candidates for TACE are HCCs that are not indications of radical treatments and within the up-to-seven criteria with well-preserved liver function.

Although TACE has been contraindicated in cases of HCC with PVTT, multiple studies have reported that it can be safely performed and may have better survival benefits than supportive care.91-94 When compared with sorafenib, median OS rates for TACE were not significantly different from those of sorafenib (9.2 and 7.4 months respectively; P = .377).95

Transarterial radioembolization

Transarterial radioembolization involves the intra-arterial delivery of glass microspheres or resin microspheres embedded with yttrium. A meta-analysis that included 284 patients with TACE and 269 with TARE showed no statistically significant difference in survival between the two groups.96 RCTs from Europe and the Asia-Pacific have evaluated the safety and efficacy of TARE in comparison with sorafenib in patients with locally advanced HCC and neither trial showed a survival benefit of TARE over sorafenib.97, 98 In a recent prospective multicentre Korean study, the 3-month tumour response rate was 57.5% and the 3-year OS rate was 75%.99 TARE might be recommended for patients who are not good candidates for TACE due to bulky tumour and/or portal vein invasion, based on published data.

Transarterial chemoembolization+molecular targeted agents

In a recent Korean randomized phase III STAH trial, in patients with advanced HCC, sorafenib with TACE did not improve OS compared with sorafenib alone.100 However, TACE coupled with MTAs or immunotherapy has been advocated in the latest Chinese guidelines. According to the TACTICS trial, sorafenib pretreatment 2-3 weeks before initial TACE and continued use after TACE showed significantly improved PFS in patients with unresectable HCC in Japan.101 There seem two concepts of TACE+MTAs treatment. The one is to reduce the frequency of on-demand TACE with MTAs. The other is to prolong MTAs treatment period by treating with TACE for uncontrolled tumour by MTAs. The candidate of former concept is TACE-suitable patients and the latter concept is applied to MTAs-suitable patients.

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy

Although HAIC is considered an experimental treatment modality and is not recommended for the treatment of HCC in Western countries, it is recommended for patients with more than four tumours or those who have failed TACE in Japan.102, 103 A recent Japanese study with propensity score matching showed that HAIC was significantly better than sorafenib in the treatment of HCC patients with macroscopic vascular invasion.104 A Korean randomized study has shown that median OS and time to progression were significantly longer for patients with advanced HCC and PVTT who received HAIC than for those who received sorafenib (14.9, 7.2 and 4.4 vs 2.7 months respectively).105

Systemic therapy

Sorafenib and lenvatinib were approved for use in the USA, EU and most Asian countries as first-line systemic therapies for HCC.34 Regorafenib, ramucirumab and cabozantinib were approved as the second-line treatment. Sorafenib-regorafenib sequential therapy extended OS from the time of sorafenib treatment initiation to 26 months (placebo group: 19.2 months), thereby providing a favourable outcome.106, 107 This outcome is almost comparable with that for intermediate stage HCC patients treated with cTACE.108

In China, FOLFOX4 was recently recommended as a clinical practice guideline.109 The rest of the East Asian guidelines recommend cytotoxic chemotherapy as a treatment option although they do not specify the type of chemotherapy preferred.13

Recently atezolizumab+bevacizumab was the first regimen to improve OS compared with sorafenib.110 The autoimmune events that occurred with atezolizumab were reported to be manageable. As a consequence of the positive finding, atezolizumab+bevacizumab has become the standard of care in first-line therapies for advanced HCC. Atezolizumab+bevacizumab is also recommended for patients with BCLC C in the ESMO e-updated HCC algorithm and for patients who will be treated with systemic therapy according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines. In Taiwan, atezolizumab+bevacizumab could be used for treating patients with unresectable HCC who have not received prior systemic therapy and who do not have a high risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Atezolizumab+bevacizumab therapy is the first-line systemic treatment that is ineligible for radical treatment or TACE.

In addition to atezolizumab+bevacizumab, at least three native programmed cell death-1 inhibitors, including sintilimab, toripalimab and camrelizumab are available in China.109

To prolong the survival time with MTAs and atezolizumab+bevacizumab, it is important to continue MTAs or atezolizumab+bevacizumab therapy as long as possible. These drugs have several adverse events. It seems a little bit hard for Asian patients to continue recommended dose of these drugs. Dose reduction in appropriate timing is very important.

4 FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

4.1 Development of immunotherapy

Phase III trials comparing nivolumab with sorafenib in front-line and pembrolizumab with placebo in second-line treatment resulted in negative results (Table 2). However, many clinical trials with immune checkpoint inhibitors or combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors and anti-VEGF agents are ongoing. Soon, some of these agents will be available in Asian countries. Clarifying the precise mechanism of tumour immunity and the tumour microenvironment will lead to the development of more potent immunotherapies for HCC.

| New MTAs which specifically affect to tumor tissue |

| Biomarkers predicting therapeutic effects and adverse events of MTA and immunotherapy |

| Evidence-based selection of MTAs in sequential therapy |

| Adaptation criteria for conversion therapy |

| Enrichment of treatment for Child-Pugh class B |

| New evaluation system for therapeutic efficacy of multiple MTAs and immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| New tumor staging system adapted to modern therapeutic strategy |

- Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTAs, molecular targeted agents.

4.2 Development of biomarkers to predict the therapeutic effects of immunotherapy and MTA

A recent integrative genomic analysis reported the possibility of stratification between an active immune class and resistance to immunotherapy, characterized by activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.111, 112 Gut microbiota has been shown to influence the therapeutic effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors in some malignant tumours.113 In HCC, the development of biomarkers for the selection of appropriate immunotherapy or MTA is urgently required.

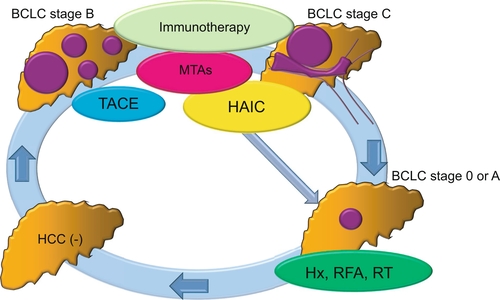

4.3 Introduction of conversion therapy

In gastric cancer, conversion therapy is defined as the use of chemotherapy/radiotherapy followed by surgical resection with curative intent of a tumour that was previously considered unresectable or oncologically incurable (Figure 2). Conversion therapy in gastric cancer has shown a high rate of R0 resection with a good prognosis.

In Asian countries, surgery provided a significant benefit for selected patients with intermediate or advanced HCC.41 With the progression of treatment with MTAs, immunotherapies and other non-radical treatments, tumour reduction in unresectable HCC has become possible. In some of these patients, radical treatments with hepatic resection or RFA were selected as the second-line treatment, resulting in a good survival benefit. RCTs are required to confirm the good prognosis of conversion therapy for patients with unresectable advanced HCC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [TT] on request.