Clinical impact of sexual dimorphism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

Funding information

The authors declare that no financial support was provided for the preparation of the manuscript.

Handling Editor: Michelle Long

Abstract

NAFLD/NASH is a sex-dimorphic disease, with a general higher prevalence in men. Women are at reduced risk of NAFLD compared to men in fertile age, whereas after menopause women have a comparable prevalence of NAFLD as men. Indeed, sexual category, sex hormones and gender habits interact with numerous NAFLD factors including cytokines, stress and environmental factors and alter the risk profiles and phenotypes of NAFLD. In the present review, we summarized the last findings about the influence of sex on epidemiology, pathogenesis, progression in cirrhosis, indication for liver transplantation and alternative therapies, including lifestyle modification and pharmacological strategies. We are confident that an appropriate consideration of sex, age, hormonal status and sociocultural gender differences will lead to a better understanding of sex differences in NAFLD risk, therapeutic targets and treatment responses and will aid in achieving sex-specific personalized therapies.

Abbreviations

-

- ACLF

-

- acute-on-chronic liver failure

-

- ADK

-

- adipokines

-

- cFT

-

- calculated free testosterone

-

- CKD

-

- chronic kidney disease

-

- DNL

-

- de novo lipogenesis

-

- FAI

-

- free androgen index

-

- FAs

-

- fatty acids

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HRT

-

- hormone replacement therapy

-

- IR

-

- insulin resistance

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MAFLD

-

- metabolic-associated fatty liver disease

-

- MRS

-

- magnetic resonance spectroscopy

-

- MS

-

- metabolic syndrome

-

- NAFLD

-

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

-

- NASH

-

- non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

-

- PCOS

-

- polycystic ovary syndrome

-

- T2DM

-

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

-

- TLR

-

- toll-like receptor

-

- US

-

- ultrasound

Key points

- In this review paper, we summarize the latest findings about the influence of sex and gender on NAFLD and NASH epidemiology, pathogenesis, progression in cirrhosis and therapies, including lifestyle modifications, pharmacological strategies and liver transplantation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are leading cause of liver disease and liver transplantation (LT) worldwide.1, 2 NAFLD/NASH are sex-dimorphic diseases, with a general higher prevalence in men.3 However, protective effect observed in fertile women seems to be lost after menopause. Thus, consideration on sex and hormonal status related to age (puberty, menopause) is critical in defining risk factors, disease prevention and treatment of NAFLD.4

Despite many of the major risk factors for NAFLD, including metabolic syndrome (MS), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and regional adiposity, are known to present clear and profound sex dimorphism, fewer publications describe sex differences in NAFLD, compared to other areas of medicine.

An appropriate attention to biological sex differences, age, hormonal status, but also gender differences, including dietary patterns, exercise and quality of life should be equally considered in the assessment of NAFLD.5 This consideration will lead to a better understanding of sex differences in NAFLD and NASH, and will aid in achieving sex-specific personalized treatments and therapies.6, 7

In this review, we summarize the main current findings about the influence of sex and gender on epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease progression, indication for LT and treatments.

2 METHODS

A literature search was performed to identify studies regarding sex and gender influence in NAFLD/NASH, published up to March 2021. Relevant research and review articles were identified by searching the PubMed database, Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBASE, limited to articles published in the English language but not date restricted.

Search terms included “fatty liver” OR “NAFLD” OR “NASH” OR “steatosis” AND “gender” OR “sex” OR “sex differences”. Additional searches were also made for each of the individual section of our review article. Selected articles referenced in these publications were also examined.

3 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF NAFLD/NASH

The incidence and prevalence of NAFLD are increasing dramatically in either Western or Eastern countries, reaching epidemic proportions.8, 9 The main reason for this dramatic increasing trend in NAFLD and NASH is the global increasing prevalence of obesity described by the World Health Organization.10 In longitudinal studies, mostly performed in Asia, the incidence of NAFLD ranges from 19 to 44.5/1000 person-years and is higher in males compared to females.11-21 The global prevalence of NAFLD has been recently updated,1, 8, 9, 22 the estimated prevalence of NASH in Europe is 23.71% (95% CI 16.12%-33.45%).23 In Italy, the Dionysos Study comprising 6,917 persons from the general population in two Northern areas found a 25% prevalence of fatty liver and was higher in males compared to females (40% vs 23%).24-26 Considering the different components of metabolic syndrome, prevalence NAFLD is dramatically high in obese patients, reaching 98%27 and in T2DM patients, 55.5% of cases, with the highest prevalence in studies from Europe (68%), whereas the prevalence of NASH is 37.3%.28

Interestingly, children carry a high risk for NAFLD, having 8%-10% prevalence of NAFLD in the Italian population.29 In a recent population-based study of young adults in UK, one in five young people had steatosis and one in 40 had fibrosis around the age of 24.30 In the US, the prevalence of NAFLD in children and adolescents increased from 3.3 between 1988 and 1994 to 10.1% between 2005 and 2010. Similarly, the prevalence of NASH increased from 0.74% to 3.4% in the same period.30, 31

The prevalence of NAFLD is higher in men than in women (Table 1, refs.11, 32-37). In particular, the prevalence of men in NAFLD cohorts ranges between 4.3% and 42%, whereas the prevalence of women ranges between 1.6% and 24%. However, among each sex group, the wide difference in prevalence can be explained by the methods for definition of NAFLD, the gold standard being, among the non-invasive techniques, the magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The role of sex and reproductive status in the development and progression of NAFLD has been focused in a recent review by Ballestri et al.38 One study from Japan15 reported that the prevalence of NAFLD in pre-menopausal women was lower (6%) than in men (24%) and in post-menopausal women (15%). Moreover, NAFLD was more prevalent in women receiving HRT than in pre-menopausal women. In Shanghai population, the prevalence of NAFLD was higher in males than females under the age of 50, but was lower in males than females among people older than 50 years.39 Analogously, a study from Japan reported a higher prevalence of NAFLD in males than females, and showed an increasing prevalence of NAFLD during adulthood from young to middle age, and a reduction of prevalence after the age of 50-60.40 In general, women are at reduced risk of NAFLD compared to men in fertile age, whereas after menopause women lose their protective effect and have a comparable prevalence of NAFLD as men.41 Post-menopausal women tend to increase body weight along with a shift in its distribution to an increase of visceral fat.42 Moreover, post-menopausal women on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) have been found to have a lower prevalence of NAFLD compared to post-menopausal women not taking HRT.43 A double-blind randomized trial with HRT or placebo in post-menopausal women with T2DM and presumed NAFLD showed a significantly decreased levels of aminotransferase in the group treated with HRT compared to placebo.44 These figures contrast with a paper in which the prevalence of NAFLD was explored in 1170 community-based adolescents in the Western Australian Pregnancy cohort.45 Females compared with males had a significantly higher prevalence of NAFLD (16.3% vs 10.1%, P =.004). In this study, the sex differences in NAFLD prevalence were associated with significant differences in adipose distribution and metabolic parameters, including adipocytokine levels. Finally, a recent review summarizes the current knowledge on sex differences in NAFLD, identifies gaps and discusses important considerations for future research.3 Indeed, gender and sex hormones interact with numerous NAFLD factors including genetic variants, cytokines, stress, environmental factors and alter the risk profiles and phenotypes of NAFLD in individuals.3

| Author | Study population | No. | Definition of NAFLD |

Prevalence of NAFLD Men Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruhl 32 | NHANES III (1988-1994) | 574 | ALT | 4.3% 1.6% |

| Clark 33 | NHANES III (1988-1994) | 15,676 | ALT or AST | 5.7% 4.6% |

| Browning 34 | Dallas Heart Study | 734 | MRS | 42% 24% |

| Ionnou 35 | NHANES (1999-2002) | 6,823 | ALT or AST | 13.4% 4.5% |

| Lazo 36 | NHANES III (1988-1994) | 12,454 | US | 20.2% 15.8% |

| Schneider 37 | NHANES III (1988-1994) | 4,037 | US | 15% 10.1% |

| Kojima 11 | University Hospital Health Checkup | 39,151 | US | 26% 12.7% |

- Abbreviation: MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; US, ultrasound

3.1 Nutritional factors and NAFLD

The dietary pattern has been investigated in several studies including NAFLD patients from different countries.46-51 All studies utilized standardized food questionnaires. In one study from US including morbid obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery, carbohydrate intake was positively correlated with NAFLD.46 Soft drink and meat intake were shown to be correlated with fatty liver in Israel,47 whereas a positive correlation with high-fat diet or high-energy intake was related with NAFLD in Portugal,48 Canada49 and Germany.50 Finally, a study from Korea showed a positive correlation between NAFLD and low vitamin C, K, folate, omega-3, nuts and seeds.51

An interesting review focused on the role of sex-specific nutrition patterns in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and including eight nutrition trials indicates that there are “typical” female patterns.52 Women of all age groups are healthier than men with regard to their food behaviour. In particular, a higher proportion of men reported eating meat and certain types of poultry than women, whereas a high proportion of women ate fruits and vegetables. Moreover, a study supported by the European Union's FAIR (agriculture, fisheries and agro-industrial sectors) program showed that overall consumption of fruit and vegetables is likely to be higher among those Europeans with high compared to low socioeconomic status.53

Interestingly, an epidemiological study examining dietary factors in NAFLD by cirrhosis status was conducted within a multi-ethnic cohort in US.54 This survey was performed prospectively in 215,000 participants in Hawaii and California. Overall, 2,974 cases of NAFLD were identified (518 with cirrhosis, 2,456 without cirrhosis); 29,474 matched controls were also analysed. Red meat, processed red meat, poultry and cholesterol intake were significantly associated with NAFLD. Conversely, fibre intake was inversely associated with the risk of NAFLD (P = .003). NAFLD was generally similar across racial/ethnic groups, except for poultry consumption (heterogeneity P = .004). The same risk factors (red meat, cholesterol) showed a strongest association in subjects with cirrhosis compared to non-cirrhotics (heterogeneity P = .004). It has been also been demonstrated that consumption of high-fructose diet beginning in adolescents lead to adult pathology that is modified by sex.55 Choline is a nutrient obtained through both dietary intake and endogenous synthesis. Indeed, choline disturbances have a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, due to the gut microbiota in determining its availability and other factors including oestrogens status and genetic polymorphism.56 Moreover, in a cross-sectional analysis of 664 subjects enrolled in the multicentre, prospective NASH Clinical Research Network focusing on diet consumption, it had been found that post-menopausal women with deficient choline intake had significantly worse fibrosis.57 Pure choline deficiency may only become apparent in post-menopausal women who carry a genetic variant in the choline synthesis pathway that have oestrogen-response elements in their promoters.58

As far as alcohol consumption is concerned, in general, this parameter is not clearly defined in the population series. Indeed, the current criteria allow alcohol intake <30 g/day for men and <20 g/day for women, but the rate of abstinent subjects remains generally unknown. A population survey including 6,462 NAFLD subjects with a 70,401 person-years of follow-up was performed to analyse risk factors of advanced liver disease.59 In the multivariate analysis, drinking habit (additional alcohol/drink/day) was an independent predictor of incident advanced liver disease.59 These results suggest that considering patients with NAFLD only two drinks per day do not protect the liver from damage but, on the contrary, promote the progression to a more severe liver disease. The relationship between average alcohol use and incidental liver disease was adjusted for age and sex separately. In fact, women are more likely than men to develop alcoholic liver disease, because of several factors including differences in body structure, volume distribution, enzymatic activity and hormones.60

It has also been demonstrated that consuming a greater percentage of the daily calories in the morning decreased the odds of steatosis by 14% and 21%. Conversely, the odds of steatosis were 20% greater when morning and midday meals were skipped or when meals were consumed late in the night (73%). Late eating also increased the probability of developing significant fibrosis (61%).61

4 PATHOGENESIS

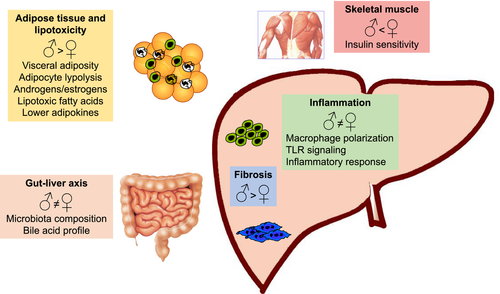

NAFLD is a multi-factorial disease where a predisposed genetic background is under the negative influence of a number of environmental and lifestyle-related factors.62 In the presence of a positive calorie balance and unfavourable genetic pattern, free fatty acids (FAs) accumulate in ‘ectopic’ tissues, including the liver,63 resulting in accumulation of fat droplets in hepatocytes. Excessive fat within the liver is associated with different degrees of lipotoxicity,64 which triggers a multicellular response to damage, leading to the development of inflammation, fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis. This process is modulated by signals deriving from extrahepatic tissues, such as the adipose tissue, the intestine and possibly the skeletal muscle.64, 65 The differences in pathogenesis based on sex are summarized in Figure 1 and are discussed in details below.

4.1 Fat accumulation and lipotoxicity

The different pattern of fat accumulation in women (gynoid obesity) is associated with reduced risk of metabolic complications.66 This may be due to the lower lipolytic response of peripheral adipocytes67 and to the effects of oestrogens, which improve sensitivity to insulin, thus reducing lipolysis and the resulting disposal of fat to the liver.68 Conversely, androgens levels in women are associated with visceral accumulation of fat and a higher metabolic risk.69 The expression of genes involved in this pathway is reduced by oestrogens.70 However, in humans fed a high fructose diet, induction of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) was more evident in women than in men,71 and ALT were found to increase to a greater extent in males than in fertile women administered fructose.72 Pre-menopausal women were protected from fructose-induced hypertriglyceridaemia because of a lower stimulation of DNL and a lower suppression of lipid oxidation.73 It is interesting to observe that lipid composition also appears to differ according to sex, pointing to qualitative modifications accompanying possible quantitative changes. In fact, in the liver of ob/ob mice, FA profiles differed between sexes, with longer chain FAs and triglycerides in males. It is of note that lipotoxic FAs were more abundant in males than in females.74 Hepatic accumulation of fat is also regulated by the metabolic effects of skeletal muscle, which is less sensitive to insulin in males.75 Testosterone promotes protein synthesis and muscular regeneration, while oestrogens attenuate inflammation.76 Moreover, oestrogen replacement therapy in post-menopausal women has beneficial effects on sarcopenia and fat accumulation.77

4.2 Inflammation

Toxic lipids can cause cell injury through oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, induction of cell death and inflammation, by innate immunity involvement.78 In addition, changes in macrophage polarization have been linked to different NAFLD phenotypes, influenced by sex differences,79 as reflected by the expression of receptors for androgens and oestrogens in macrophages, and the fact that androgens promote polarization towards an M2 phenotype.80 There are also sex-dependent differences in macrophage expression of the pattern recognition receptor, TLR-4, and in activation of downstream signalling.81 In general, the ability of macrophages to mount a detrimental inflammatory response is greater in males, at least in rodent models.3

4.3 Adipose tissue dysfunction

Adipose tissue is not only the source of free FAs that contribute to generating hepatic triglyceride accumulation, but also of a number of proteins, collectively known as adipokines (ADK), which act at distant sites regulating metabolic functions, inflammation and tissue repair.82 Leptin amplifies inflammation and drives profibrogenic functions; adiponectin promotes insulin sensitivity and dampens inflammation and fibrosis. Secretion of ADK is markedly different in males and females,83 and in general, ADK levels are higher in the latter. Increased resistance to leptin in females may be an additional mechanism underlying higher levels of this ADK,84 although whether this translates into a different regulation of the hepatic response to fat accumulation is uncertain. Prohibitin has been shown to play a role in sex differences in adipose tissue functions, possibly regulating the sex differences in many pathophysiological conditions, such as obesity, IR and metabolic dysregulation.85

4.4 Gut microbiota

Dysbiosis defines quantitative and qualitative changes of gut microbiota composition, and has been associated with development of metabolic abnormalities, NAFLD and cirrhosis.64 Alteration in gut microbiota may contribute to NAFLD directly, via products of bacteria metabolism, or increasing the extraction of calories from food. Increased gut permeability associated with dysbiosis participates in the pathogenesis of chronic low-grade inflammation and result in activation of toll-like receptor such as TLR-4 in the liver, triggering pathways implicated in progression of liver diseases, including NAFLD. In addition, microbiota modulates FXR activation in the intestine, and the resulting secretion of FGF 15/19.64 Heterogeneity in microbiota composition according to sex has been demonstrated86 and could contribute to confer a different cardiovascular risk.87 A recent study, indeed, demonstrated that the relationship between gut microbiota and metabolic disease seems to be sex-dependent and this might determine the differences in the predisposition to develop the MS between women and men.64 According to these data, a possible impact on the pathogenesis of metabolic-induced liver diseases is likely.79 Menopausal status is an additional factor influencing the microbiota.88 Along these lines, the profile of bile acids in mice differs based on sex and age.89

5 END-STAGE LIVER DISEASE AND ACUTE-ON-CHRONIC LIVER FAILURE

The prevalence of cirrhosis among 492 biopsy-proven NASH patients was higher in women (57%) than in men (43%).90 In a study on 144 patients with NAFLD, sex was not an independent risk factor for the progression of fibrosis, while, at multivariate analysis, older age (>45 years), obesity, presence of diabetes and AST/ALT ratio>1 were independent significant predictive factors of severe fibrosis.91

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is characterized by multiple organ failure with high short-term mortality. Despite ACLF incidence due to NASH is lower when compared to other aetiologies, it is the fastest growing liver disease aetiology among all ACLF hospitalizations, as demonstrated in a recent US population-based study.92 In this study, the authors detected an exponentially increased frequency of ACLF admissions for NASH aetiology with 12% of NASH-related ACLF in 2006-2008, 33% in 2009-2011 and 55% in 2012-2014. NASH-ACLF patients are more frequently women (60%) and older than in other aetiologies, with a more severe course characterized by higher mortality, more frequent need of dialysis and higher length of stay. Metabolic derangements such as obesity and diabetes might also play a confounding role in the pathophysiology, clinical course and prognosis of NASH patients with ACLF.93

6 NASH AND HCC

In Europe, NASH is an increasingly common aetiology for HCC.94 The yearly cumulative incidence of HCC is 2.6% in patients with NASH-related cirrhosis.95 Irrespective of its aetiology, HCC predominantly affects males with an incidence four times higher in males than females.96 The reasons for this sex disparity are complex and may be associated with a protective role of oestrogen on HCC development,97 until menopause. For this reason, the median age for women is higher than that of men at the time of HCC diagnosis. Most studies showed that men are more likely to have larger tumours with increased rates of macrovascular invasion and extrahepatic spread, and are more likely to undergo transplantation than women.98, 99 The pathogenesis of HCC in the context of NAFLD is not completely clear; importantly 20% of NAFLD-HCC are diagnosed in the setting of non-cirrhotic liver.100-102 Grade-based recommendations for surveillance in patients with NASH did not justify a systematic surveillance in NAFLD patients without cirrhosis, as a result of low currently observed incidence of HCC in this setting.103 Older age, diabetes, advanced fibrosis and obesity are the main risk factors associated with HCC development in NAFLD patients, with or without cirrhosis.104-106 In a US multicentre retrospective study,107 the authors showed that there was significantly more non-cirrhotic HCC in women than in men. This may reflect the large number of NAFLD-related HCC in women in the cohort. This is very important from a surveillance point of view. Finally, they found that women had less-advanced HCC and had a greater overall survival, leading to different treatment options. Even when HCC is diagnosed at a potentially curable stage, LT or resection is not always feasible because of obesity and comorbidities. However, there have been excellent long-term outcomes in patients undergoing liver resection,108 loco-regional therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, selective internal radiotherapy and transarterial chemoembolization can also be proposed.109-113 Sex has a role also in HCC treatment, related to different tumour morphology at diagnosis, as men present larger HCC than women. Moreover, some studies showed that oestrogen can reduce the activation of stellate cell, making slower the liver fibrinogenesis.107 Thus, women are less likely to have complications such as portal vein thrombosis and renal dysfunction, which may prevent HCC curative treatments. For both reasons, curative treatments for HCC are more common in women than men.114-116 Sobotka et al115 confirmed that women are still more likely to undergo resection and also determined that women are more likely to undergo ablation because of more compensated liver disease, being NAFLD present similarly in the 2 groups.

In conclusions, women show frequently a more compensated liver disease compared to men, developing non-cirrhotic HCC-related NAFLD. Moreover, at diagnosis, women have smaller tumour than men, more amendable to curative HCC treatments.

7 NASH AS INDICATION FOR LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

NASH has become the leading indication for LT in the US117 and NASH/HCC is the most rapidly growing in the waiting list for LT.118 NASH was the second cause for LT globally in the last years, the leading cause for LT for women, the second leading cause for men and the leading cause by 2016 among Asian, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white females.119 In Nordic countries, NAFLD was the second most rapidly increasing indication for LT between 1994 and 2015, going from 2% in 1994-1995 to 6.2% in 2011-2015.120 A recent Italian monocentric study highlighted that the proportion of NASH patients listed for LT significantly increased from 5% to 9.5% after the introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV, also showing a significant increase of those listed for HCC (from 2% to 5.9%).121

7.1 Pre-transplant workup – Assessment of operative risk

The selection process among patients with NASH can be particularly challenging among all LT candidates, as they are most likely to carry risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Cirrhotic female patients have been found to have decreased levels of oestrogen, progesterone and luteinizing hormone, frequently becoming amenorrhoeic. It would, therefore, seem possible that the potential protective effect of oestrogens may be reversed in the context of end-stage liver disease, failing to protect them against potential cardiovascular complications during and after LT. Moreover, women with NASH present a significantly high incidence of non-liver cancers, especially breast cancer, which may be related to its known association with diabetes, obesity and MS.122 Therefore, even though women have lower MELD scores than men as a result of lower median creatinine levels with the same degree of renal impairment, the higher number of women listed, together with the fact that NASH is becoming the first indication for LT, could theoretically outweigh the disadvantage previously posed for women to LT access for other indications. Nevertheless, in a recent ELTR analysis, the overall number of LT performed in Europe constantly increased until 2007; however, the percentage of male patients significantly increased over time, whereas female recipients significantly decreased.123 Thus, NASH women remain longer on the waiting list for transplant, are more likely to be removed, have a higher risk of death and are less likely to receive LT compared to men with NASH, even when adjusting for potential confounding covariates. As a matter of facts, when the authors compared NASH patients to HCV patients, the magnitude of sex discrepancy resulted higher in NASH patients,124 meaning that other unknown or unintentional biases exist in organ allocation.

7.2 Renal dysfunction in patients transplanted for NASH

NASH has been recognized as an independent factor of stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) after LT; the reason for this independent association seems to be related to the chronic inflammatory state associated with a high level of circulating inflammatory cytokines.125 In contrast to general population,5 female sex is a risk factor for a faster decline in kidney function after solid organ transplants.126

A multicentre observational study published on LT recipients showed that female sex was an independent prediction factor of CKD stage 3 at 1 and 5 years and female patients had a faster decline in eGFR than men,127 confirming the sex difference already showed in renal transplant recipients.128 Women may have a higher susceptibility to calcineurin inhibitors mediated kidney injury, but the reason for the discrepancy between transplant recipients and the general population has not been completely identified. These data suggest the need for sex-based personalized approaches to identify the best strategies to prevent the decline of kidney function after LT.

7.3 Long-term post-transplant complications

De novo MS is a frequent complication in LT recipients overall, showing a progressive increase overtime. Non-modifiable risk factors for allograft steatosis and/or NASH include age, genetics, sex and pre-existing cardiovascular diseases. Female sex is a possible risk factor for steatosis after transplant but features of MS were found to be more frequent in males in an Italian cohort of LT recipients.129 Furthermore, male patients presented a significantly lower survival rate when transplanted for metabolic disease compared with female patients in a European study123 ; however, this results still need to be confirmed in other cohorts before an accurate interpretation can be drawn. Besides sex differences, a recent meta-analysis examining 17 studies, representing 2,378 post-LT patients, found the 5-year incidence rates for recurrent NAFLD to be 82% and the rate of cirrhosis from 1% to 11%.130 Sepsis accounted for a mortality of 4%-16% in recipients with NASH and 1% to 8% in recipients without NASH.118 Infection and cardio/cerebrovascular complications were the commonest causes of death in NASH patients without HCC in a European study. Moreover, female sex, extreme low or high recipient BMI and age >60 years and low or high recipient BMI independently predicted death in those patients.131 Thus, careful assessment and selection of patients will be critical to maintain acceptable survival in those transplanted for NASH, which should be better defined considering sex differences.

8 LIFESTYLE INTERVENTION IN NAFLD/NASH PATIENTS

The main strategy to treat NAFLD focuses on the control of underlying risk factors like diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and other comorbidities. Since no effective pharmacological treatment for NAFLD/NASH has been approved, the lifestyle changes, consisting of balanced diet and physical activity represent the cornerstone of intervention for NAFLD treatment.132

Recent studies have reported that a 6- to 12-month widespread lifestyle modification, based on reduced energy intake and increased physical activity, leads to improvement in liver enzymes and metabolic parameters, and reduced steatosis and necroinflammation, including ballooning and fibrosi.133-135 The most recent European and American guidelines recommend that lifestyle interventions should be included as part of the clinical care of all NAFLD patients, regardless of the stage of disease.136, 137

Preclinical studies demonstrated in animal models that males and females react differently to caloric restriction and intermittent fasting,138 but clinical human data are still deficient. Only few studies have explored whether sex differences affect weight loss after surgical and non-surgical treatments, achieving conflicting results.139, 140 In general, with lifestyle interventions, men lose more weight and present greater metabolic benefits compared to women.141 This higher metabolic effect could be partly explained by the fact that during weight loss, men lose mainly visceral adiposity compared with women, who principally lose subcutaneous adiposity.142, 143

Similarly, in NAFLD patients, higher histological improvement was observed in men than women after weight loss. In fact, in male patients, a modest weight loss, between 7% and 10%, produces a significant histological improvement, while in women a more consistent weight loss (>10%) is necessary to obtain the same effect.144

It is well known that inadequate physical activities and sedentary lifestyle are risk factors for NAFLD.145 Considering this aspect, women are generally more sedentary and have a lower tendency to meet physical activity guidelines. However, they showed a stronger beneficial effect of increased physical activity against NAFLD compared to men. Indeed, the physiological response to exercise appears to be different in men and women because of the different composition of the muscle fibres and different lipid metabolism.66, 146 Women's muscle is characterized by a higher number of type I muscle fibres which has higher capabilities of lipid oxidation, a higher content of intramyocellular lipids and are more sensitive to insulin than men's muscle.147

Some attention should be paid to post-menopausal women, in whom significant weight reduction achieved through dietary restrictions can induced negative effects on lean muscle and bone mass.148 To prevent this side effect, an integrated approach consisting of dietary changes along with regular resistance training or aerobic exercises is mandatory.148, 149 However, only few studies have specifically assessed the role of physical activity in NAFLD post-menopausal women. The available data, however, confirm that physical activity and exercises effectively reduce liver enzymes in overweight post-menopausal women, probably because of the reduction in liver fat content and as the same time reduce cardiovascular risk factors.150, 151

Thus, optimal lifestyle modifications may differ between men and women, or between pre- and post-menopausal women. However, this topic is still largely unexplored, so these important questions should be better addressed in future interventional clinical trials.

9 PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT FOR NASH

Despite the high prevalence of NAFLD worldwide, currently there is no effective pharmacological treatment for NAFLD/NASH. The current therapies mainly focus on metabolic disorders associated with NAFLD.152

Regardless the clear sexual dimorphism of NAFLD/NASH, very few studies on possible therapeutic strategies deal with sex differences or consider natural age-related hormone fluctuations as a disease-modifying factor. A recent Chinese study has found pioglitazone to be more efficient in reducing liver fat content in NAFLD female than in male diabetic patients.153

A phase 2b study on MK-3655 (an insulin sensitizer) in pre-cirrhotic NASH is currently recruiting men and post-menopausal women (NCT04583423). Whether this patient selection will lead to the evaluation of sex-specific outcomes is not reported.

Most of the sex-specific studies on NAFLD therapy are targeted at sex hormones supplementation or inhibition; meanwhile, data on sex- and age-specific response to drugs in phase 3 trials are lacking (Table 2).

| Drug | Study phase | Participants | Study name | Population treated | Status (references or Clinical trial number) | Main adverse events | Male/Female included | Sex-related outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farnesoid X receptor agonist | ||||||||

| Obeticholic acid | 3 | 1968 | REGENERATE | F2-F3, or F1 with at least one accompanying comorbidity among obesity, T2DM, or ALT >1.5 × upper limit of normal |

Ongoing, interim analysis at 18 months172 NCT02548351 |

Dose-related pruritus, Increased LDL cholesterol |

M = F | Not reported |

| 3 | 919 | REVERSE | Compensated NASH-F4 |

Ongoing NCT03439254 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| Tropifexor (LJN452) | 2b | 198 | FLIGHT-FXR | NASH F1-F3 or clinical NASH+obesity + T2DM |

Part A and B completed,173 part C interim analysis at week 12 174 NCT02855164 |

Mild pruritus Dose-dependent slight increase in LDLc and HDLc |

M = F | Not reported |

| Cilofexor (GS 9674) | 2 | 140 | Non-cirrhotic NASH by MRI-PDFF≥8% and liver stiffness ≥2.5 kPa by magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) |

Completed 175 NCT02854605 |

Moderate-to-severe dose-dependent pruritus | F > M | Not reported | |

| EDP-305 | 2b | 336 | ARGON-2 | NASH F2-F3 biopsy proven |

Recruiting NCT04378010 |

---- | All | ---- |

| 2a | 134 | ARGON-1 | Non-cirrhotic NASH by MRI-PDFF≥8% and biopsy/phenotype |

Completed 176 NCT03421431 |

pruritus, (GI)-related symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea), headache and dizziness. | All | Not reported | |

| Nidufexor | 2 | 122 | NASH and diabetic nephropathy | Completed 177 NCT02913105 | ----- | F > M | Not reported | |

| EYP001a | 2a | 160 | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT03812029 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| TERN-101 | 2 | 96 | LIFT | Non-cirrhotic NASH |

Ongoing NCT04328077 |

----- | All | ---- |

| IKKβ inhibitor | ||||||||

| Diacerein | 3 | 84 |

NAFLD T2DM |

Completed 178 | Not reported | F > M | Not reported | |

| Angiotensin II blockers (ARB) | ||||||||

| Losartan | 3 | 45 | FELINE | NASH F1-F3 | Completed 179 | Well tolerated | M = F | Not reported |

| Pan-caspase inhibitor | ||||||||

| Emricasan (IDN-6556) | Pilot study | 23 | Compensated cirrhosis | Completed 180 | Well tolerated | M > F | Not reported | |

| 2 | 263 |

NASH cirrhosis and HVPG ≥12 mmhg Compensated cirrhosis (72%) |

Completed 181 | Well tolerated | M = F | Not reported | ||

| 2b | 318 | ENCORE-NF | NASH F1-F3 | Completed 182 | Not reported | M = F | Not reported | |

| Thiazolidinedione (TZD) | ||||||||

| PXL065 | 2 | 120 | DESTINY 1 | NASH F0-F3 |

Ongoing NCT04321343 |

----- | All | ---- |

| Pioglitazone | 4 | 176 | UTHSCSA NASH Trial |

NAFLD T2DM |

Completed 183 NCT00994682 |

weight gain | M > F | Not reported |

| PPAR Agonist | ||||||||

| Elafibranor | 3 | 1070 | RESOLVE-IT | NASH F2-F3 | Terminated after interim analysis: endpoints not met 184 NCT02704403 | --- | M > F | Not reported |

| Lanifibranor (IVA337) | 2b | 247 | NATIVE | NASH F0-F3 |

Completed 185 NCT03008070 |

Moderate dose-dependent weight gain | F > M | Not reported |

| 2 | 84 |

NAFLD T2DM |

Ongoing NCT03459079 |

--- | All | --- | ||

| Seladelpar (MBX-8025) | 2b | 181 | NASH F1-F3 | NCT03551522 | Temporarily suspended due to interface hepatitis | All | ---- | |

| Saroglitazar | 2 | 106 | EVIDENCES VI | NASH F0-F3 | NCT03863574186 | ---- | All | Not reported |

| Pemafibrate (K-877) | 2 | 100 | NAFLD |

Active, not recruiting NCT03350165 |

---- | All | --- | |

| Inhibitor of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCi) | ||||||||

| Firsocostat (GS-0976) | 2 | 127 | NASH F1-F3 | NCT02856555187 |

Hypertriglyceridaemia, Nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and headache |

F > M | Not reported | |

| Gemcabene | 2a | 6 | NAFLD |

Terminated due to lack of efficacy and safety concerns NCT03436420 |

---- |

Paediatric, All 12-17 years |

---- | |

| PF-05221304 | 2a | 305 | NASH/ NAFLD | NCT03248882188 | Hypertriglyceridaemia, abdominal distention, nausea | F > M | Not reported | |

| CCR2/CCR5 Inhibitor | ||||||||

| Cenicriviroc | 2b | 289 | CENTAUR | NASH F1-F3 | NCT02217475 189 | Headache, fatigue, diarrhoea | M > F | Not reported |

| 3 | 2000 | AURORA | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT03028740 |

--- | All | ----- | |

| Leronlimab (PRO 140) | 2 | 90 | NASH F0-F3 |

Not yet recruiting NCT04521114 |

---- | All | ---- | |

| Thyroid hormone receptor beta agonist | ||||||||

| Resmetirom (MGL-3196) | 3 | 2000 | MAESTRO_NASH | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT03900429 |

----- | All | ---- |

| 2 | 125 | NASH F1-F3 | NCT02912260190 |

Diarrhoea, nausea |

F > M | Not reported | ||

| VK2809 | 2b | 337 | VOYAGE | NASH F1-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04173065 |

----- | All | ---- |

| Galectin-3 Inhibitor | ||||||||

| Belapectin (GR-MD-02) | 2b/3 | 1010 | NASH cirrhosis |

Recruiting NCT04365868 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| 2 | 162 | NASH-CX | NASH cirrhosis and portal hypertension | NCT02462967191 | Well tolerated | F > M | Not reported | |

| Monoclonal antibody against lysyl oxidase-like 2 | ||||||||

| Simtuzumab (GS-6624) | 2b | 219 | NASH F3-F4 | Completed 192 | Rates of adverse events were similar among groups. | F > M | Not reported | |

| 2b | 258 | Compensated cirrhosis | Completed 192 | Not reported | Not reported | |||

| AMPK activators | ||||||||

| PXL 770 | 2 | 120 | STAMP-NAFLD | NAFLD | NCT03763877193 | Well tolerated | All | Not reported |

| Oltipraz (PMK-N01GI1) | 3 | 144 | NAFLD |

Ongoing (NCT04142749) |

--- | All | --- | |

| Omega-3 fatty acid | ||||||||

| Omacor (Lovaza) | 4 | 103 | WELCOME | NAFLD | Completed 194 | Rates of adverse events were similar among groups | M = F | Not reported |

| Antioxidant | ||||||||

| Vitamin E | 2 | 236 | NASH F3- F4 | Completed 195 | Not reported | F > M | Not reported | |

| Berberin | 4 | 120 | EASYBEinNASH | NASH |

Recruiting NCT03198572 |

---- | All | ---- |

| Resveratol | 3 | 10 |

NAFLD T2DM in adolescent |

Completed 196 | ---- | All | ---- | |

| Stearoyl-CoA desaturase1 (SCD1) Inhibitor | ||||||||

| Aramchol | 3/4 | 2000 | ARMOR | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04104321 |

----- | All | ---- |

| 2b/3 | 247 | Aramchol005 | Non-cirrhotic NASH | NCT02279524197 | Headache, nausea, UTI | F > M | Not reported | |

| Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) analogue | ||||||||

|

Efruxifermin AKR-001 |

2a | 110 | BALANCED | NASH F1-F4 | NCT03976401198 | mild/moderate gastrointestinal events and injection site reactions | All | Not reported |

| Pegbelfermin (BMS-986036) | 2b | 160 | FALCON 1 | NASH F3 |

Ongoing NCT03486899 |

------ | All | ---- |

| 2b | 152 | FALCON 2 |

NASH compensated cirrhosis |

Ongoing NCT03486912 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| 89BIO-100 | 2 | 81 | NASH/NAFLD | NCT04048135 | ---- | All | ---- | |

| Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) analogue | ||||||||

|

Aldafermin (NGM 282) |

2b | 152 | ALPINE 2/3 | NASH F2-F3 |

Ongoing NCT03912532199 |

LDL increase, well tolerated |

F > M | Not reported |

| 2b | 150 | ALPINE 4 | NASH F4 compensated |

Recruiting NCT04210245 |

----- | All | ----- | |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist | ||||||||

| Dulaglutide | 4 | 93 | REALIST | NASH F2-F3 |

Not yet recruiting NCT03648554 |

----- | All | ---- |

| Exenatide | 4 | 13 | NAFLD |

Completed (NCT01208649) |

Not reported | All | Not reported | |

| Liraglutide | 2 | 52 | LEAN | NASH F1-F4 | NCT01237119200 | Diarrhoea, nausea | M > F | Not reported |

| Cotadutide (MEDI0382)* | 2 | 72 | NAFLD/NASH F1-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04019561 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| 2b | 834 | NAFLD, obesity and T2DM | NCT03235050201 |

Nausea, vomiting |

F > M | Not reported | ||

| HM15211 | 2 | 112 | NASH F1-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04505436 |

---- | All | ---- | |

| Tirzepatide (LY3298176) | 2 | 196 | SYNERGY-NASH | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04166773 |

---- | All | ---- |

| Semaglutide | 2 | 320 | NASH F1-F3 | NCT02970942202 | Nausea, constipation, vomiting | F > M | Not reported | |

| Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) inhibitor | ||||||||

| MSPC-0602K | 3 | 1800 | NAFLD/NASH T2DM |

Ongoing NCT03970031 |

----- | All | ----- | |

| 2b | 402 | EMMINENCE | NASH F1-F3 | NCT02784444203 | Modest weight gain | F > M | Not reported | |

| PXL065 | 2 | 120 | NASH F0-F3 |

Ongoing NCT04321343 |

----- | All | ----- | |

| Drug combining regimen | ||||||||

|

Cilofexor Firsocostat Selonsertib |

2b | 392 | ATLAS | F3-F4 | NCT03449446204 | Pruritus | F > M | Not reported |

|

Cilofexor Firsocostat Selonsertib Fenofibrate/ Vascepa |

2 | 220 | NASH/NAFLD |

Active, not recruiting NCT02781584 |

---- | All | ---- | |

|

Semaglutide Firsocostat Cilofexor |

2 | 109 | NASH F2-F3 | NCT03987074205 | Pruritus, GI events | ---- | Not reported | |

|

Cenicriviroc Tropifexor |

2 | 193 | TANDEM | NASH F2-F3 |

Ongoing NCT03517540 |

---- | All | ---- |

| Tropifexor Licogliflozin | 2 | 380 | ELIVATE | NASH F2-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04065841 |

---- | All | ---- |

| PF-06865571 PF-05221304 | 2 | 450 | MIRNA | NASH |

Recruiting NCT04321031 |

---- | All | ---- |

|

Selonsertib (GS-4997) Simtuzumab |

2 | 72 | NASH F2-F3 | NCT02466516206 | Well tolerated | F > M | Not reported | |

| LYS006 Tropifexor (LJN452) | 2 | 250 | NEXSCOT | NAFLD/NASH |

Recruiting NCT04147195 |

----- | All | ---- |

| Elobixibat Cholestyramine | 2 | 100 | NAFLD/NASH |

Recruiting NCT04235205 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| Semaglutide Empagliflozin | 4 | 192 | COMBAT_T2_NASH | NASH F1-F3 T2DM |

Not yet recruiting NCT04639414 |

----- | All | ---- |

|

Empagliflozin Pioglitazone |

4 | 60 |

NAFLD T2DM |

Recruiting NCT03646292 |

||||

|

Alogliptin Pioglitazone |

4 | 60 |

NAFLD T2DM |

Recruiting NCT03950505 |

---- | All | ---- | |

|

Saroglitazar Vitamin E Lifestyle Modification |

3 | 250 | NAFLD/NASH |

Not yet recruiting NCT04193982 |

----- | All | ---- | |

| Vitamin E and DHA-EE | 2 | 200 | PUVENAFLD | NAFLD |

Recruiting NCT04198805 |

----- | All | ---- |

|

Vitamin E Pioglitazone |

3 | 247 | PIVENS | NASH F1-F3 | NCT00063622207 | Weight gain | F > M | Not reported |

| Sodium-glucose co-transporter SGLT1/2 | ||||||||

| Dapagliflozin | 3 | 100 | DEAN | NASH |

Recruiting NCT03723252 |

---- | All | ---- |

| Licogliflozin (LIK066) | 2 | 107 | NASH F1-F3 | NCT03205150208 | diarrhoea | M > F | Not reported | |

| Apoptosis Signal-Regulating Kinase (ASK1) inhibitor | ||||||||

| Selonsertib (GS-4997) | 3 | 883 | STELLAR 4 | NASH F4 compensated | NCT03053063209 | Terminated early due to lack of efficacy | F > M | Not reported |

| Selonsertib (GS-4997) | 3 | 808 | STELLAR 3 | NASH F3 | NCT03053050209 | Terminated early due to lack of efficacy | F > M | Not reported |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | ||||||||

| Spironolactone | 1/2 | 30 | NASH F0-F3 |

Recruiting NCT03576755 |

---- | Only F, aged 18-45 | --- | |

| Miricorilant | 2 | NCT03823703 | ||||||

| Diacylglycerol-acyl transferase 2 (DGAT2) Inhibitor | ||||||||

| PF06865571 | 2a | 99 | NAFLD |

Completed NCT03776175 |

--- | M > F | No reported | |

| Inhibitor of Ketohexokinase | ||||||||

| PF-06835919 | 2a | 150 | NAFLD T2DM |

Recruiting NCT03969719 |

---- | All | ----- | |

| LPCN 1144 (testosterone) | 2 | 75 | LIFT |

NASH MELD <12 |

Recruiting NCT04134091 |

---- | Only M, aged 18-80 | ----- |

|

MK-3655 (NGM313) Monoclonal insulin sensitizer |

2b | 328 | MK-3655-001 | Non-cirrhotic -NASH |

Recruiting NCT04583423 |

---- | M aged 18-80 and post-menopausal women | --- |

| Icosabutate | 2b | 264 | ICONA | NASH F1-F3 |

Recruiting NCT04052516 |

--- | All, proportion unknown | --- |

- Abbreviation: NAFLD: Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; NASH: non-alcoholic steatosis hepatitis; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index; HVPG: Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient

- * dual receptor agonist that stimulates glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 activity

9.1 Potential sex-specific therapy

9.1.1 Oestrogen

Experimental data suggest that oestrogen is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease.38, 41 Oestrogen therapy in liver disease, besides improving several clinical conditions associated with menopause,154 has demonstrated a protective effect on NAFLD in patients with diabetes.44, 155, 156 One of these studies demonstrated that post-menopausal women receiving oestrogen and medroxyprogesterone showed a lower risk of diabetes.155 Oestrogen therapy reduced the serum levels of IL-6, ALT, AST and ALP in post-menopausal women with T2DM.156 In a study by Hamaguchi et al, the incidence of NAFLD in women taking HRT was higher than in pre-menopausal women, but lower than in menopausal women. HRT was not associated with increased risk of incident NAFLD.15

Since diabetes is a well-known risk factor for NAFLD/NASH,157 and clinical trials using oestrogen therapy in diabetes suggest that this treatment reduces the risk of NAFLD/NASH in post-menopausal women.158

The extension of oestrogen therapy to male NAFLD/NASH patients is still in preclinical phase.159, 160

9.1.2 Testosterone

As far as can be deduced from the available data, testosterone seems to have opposite effect on liver steatosis in men and women.

Most data on the effects of testosterone on NASH in women derive from populations affected by polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), in whom high testosterone increases the risk of NAFLD independently of obesity and insulin resistance.161

Women with hyperandrogenic PCOS have more severe hepatic steatosis as compared to the less common PCOS phenotype marked by normal androgens.162

The influence of high testosterone on NAFLD seems to be true for adult females regardless of age. In general, testosterone peak is reached in late adolescence and declines gradually over the next two decades, but remains stable across menopause and beyond.163

9.1.3 Pre-menopausal Women

A recent study on 207 pre-menopausal women with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD has found a more than two-fold higher risk of NASH, as well as NASH fibrosis, with increasing quartiles of free testosterone in women aged 22-27.164

A study by Park JP et al have found a positive association between serum testosterone level and US-diagnosed NAFLD in pre-menopausal, but not in post-menopausal women.165

CARDIA cohort data on young women aged 18-30 years upon enrolment showed that increasing quintiles of free testosterone were associated with prevalent NAFLD at 25 years of follow-up. Of note, this association persisted among women without androgen excess. This study utilized a computed tomography (CT) quantification of hepatic steatosis.166

9.1.4 Post-menopausal Women

In a study on a small group of post-menopausal women with biopsy-proven NAFLD, the NAFLD group had higher values of calculated Free Testosterone (cFT), bioavailable testosterone and Free Androgen Index (FAI), despite exhibiting similar to control levels of serum total testosterone. Serum sex hormone-binding globulin levels, bioavailable testosterone and FAI, but not cFT, were associated with NAFLD independently of age, body mass index and waist circumference.167

On the basis of a cross-sectional analysis using data from the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, post-menopausal women with high levels of bioavailable testosterone are at greater risk for fatty liver.168

9.1.5 Androgen-Blocking Drugs

A competitive inhibitor of testosterone receptors, Spironolactone has shown good safety profile and tolerability in the treatment of hyperandrogenism symptoms. A recent trial in patients with histologically proved NAFLD found spironolactone plus vitamin E to improve markers of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance as compared to vitamin E alone.169

Spironolactone is being evaluated in a pilot study (NCT03576755) in women of childbearing age (18-45 years) with NASH, to better understand the role of androgens in NASH.

9.1.6 Testosterone in Men

In men, lower testosterone levels are associated with imaging-confirmed NAFLD.170 In a recent biopsy-proven NASH/NAFLD study,171 men with low testosterone were more likely to have NASH with advanced fibrosis versus NAFLD.

A currently recruiting phase 2 study in adult men with biopsy confirmed that NASH (NCT04134091) is aimed at evaluating efficacy and tolerability of LPCN 1144, an oral prodrug of bioidentical testosterone.

10 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although sex differences exist in the prevalence, risk factors, fibrosis and clinical outcomes of NAFLD, our understanding of sex differences in NAFLD has remained significantly more limited so far, compared to other areas of medicine. To fill this gap, more accurate epidemiological and pathophysiological data obtained from larger cohort studies are needed.

The future direction in the management of NAFLD/NASH patients – regardless the gender – should be the early identification of NAFLD to prevent progression to fibrosis and NASH. Moreover, detailed program of education, especially in the young population at risk of develop overweight, obesity and liver steatosis should be developed.

Therefore, an appropriate consideration of sex, age, hormonal status and sociocultural background will lead to a better understanding of sex differences in NAFLD risk, and will aid in personalization of therapies. In addition, it is mandatory to stimulate the design of clinical studies aimed at sex and gender differences in NASH therapy to better characterize sex-specific therapeutic targets and responses.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.