Beyond the achievement of sustained virological response after liver transplantation

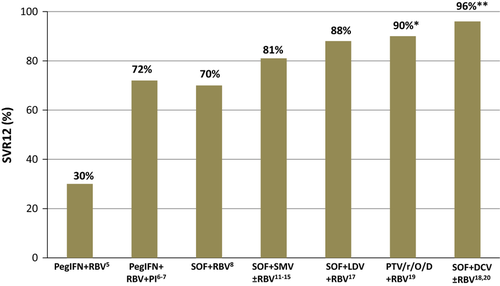

Graft and patient survival are significantly lower in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients than in patients who undergo transplantation for other causes 1, because of the accelerated course of hepatitis C recurrence 2. Antiviral therapy is associated with improved outcomes among patients who achieve a sustained virological response (SVR), both in individuals with severe and mild disease recurrence 3-5. However, treatment with peg-interferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) in this setting had a low efficacy (~30%) and a poor tolerability and safety profile. For this reason, over the last years, a significant proportion of HCV-infected liver transplant recipients were left with no therapeutic alternatives, progressing to cirrhosis, retransplantation or even death.

The addition of the first-generation protease inhibitors (telaprevir, boceprevir) to Peg-IFN and RBV improved SVR rates in patients with genotype (GT) 1 infection (~50–70%), but it was associated with increased toxicity 6, 7. The development of direct acting antivirals (DAA) and their combination in interferon-free regimens has deeply impacted the prognosis of patients with hepatitis C recurrence 8, 9.

Sofosbuvir (SOF) and Simeprevir (SMV) were the two-first DAA to be approved in the USA and Europe. Despite that this combination had not been evaluated in any clinical trial in liver transplant setting, its use was rapidly extended in clinical practice based on the encouraging results of the COSMOS trial in immunocompetent patients 10. In fact, in the last two international meetings, accumulating reports from the use of SOF plus SMV in the liver transplant setting have been presented with overall good results 11, 12.

The study by Saab et al. 13, published within this issue of Liver International, reports the results of a retrospective cohort of 30 liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C recurrence treated with the combination of SOF and SMV (without RBV) for 12 weeks. Consideration for antiviral treatment was the presence of increased transaminases and the absence of allograft rejection. Patients were treated at a median time of 6 years after LT. The majority of patients (57%) had no histological evidence of graft fibrosis (F0-F1) and 43% had been previously nonresponders after LT (two patients had received SOF plus RBV). The authors report an overall SVR rate of 93% with two patients presenting viral relapse during follow-up (both of them with advanced liver fibrosis in the graft). The safety profile was good, with no need for treatment discontinuation, or use of supportive therapy. The authors made no specific considerations regarding immunosuppresion during treatment, except for the need of standard adjustments according to serum drug levels.

Although SOF plus SMV was temporarily the only available oral regimen, this therapy is currently one more alternative in the antiviral armamentarium and has been overtaken by other antiviral combinations. Saab et al. 13 endorse the use of SOF plus SMV in the transplant setting by reporting very good SVR rates (93%) in a small cohort of 30 liver transplant recipients in a single center. Its excellent tolerability (mainly because of the absence of RBV) and its short duration (12 weeks) were also factors favouring the selection of this combination. However, it should be taken into account that patients included in this small series were easy-to-treat individuals 3. Whether these encouraging results could be extrapolated to more complex HCV LT recipients is less obvious. Indeed, the only two patients suffering viral relapse were previous nonresponders and had already advanced fibrosis in the graft.

Real-world data from large multicentric cohorts of patients treated with SOF/SMV were presented in the last AASLD and EASL meetings 11, 12 reporting overall SVR rates around 90% and supporting the use of this combination in GT1 patients. The addition of RBV did not seem to impact on overall SVR rates in none of these cohorts, which is an important point because of the lack of controlled studies using RBV-free DAA combinations in this setting. Nevertheless, SVR was significantly reduced when considering only those patients with graft cirrhosis (85% in cirrhotics, and 77% in those with MELD>10). Moreover, SVR rates were slightly lower in individuals infected with genotype 1a than 1b 14, 15 (in the current study only G1-infected patients were included but data on the subgenotype are missing). Another major consideration regarding the combination of SOF/SMV is its limited applicability among patients with advanced liver disease. SMV concentrations increase significantly in patients with Child–Pugh B and C decompensated cirrhosis and it is not recommended in this setting, thus restricting its use to patients with compensated cirrhosis. In addition, SMV may induce a reversible increase in bilirubin levels because of a competitive effect on bile hepatocellular transporters, which may become a confounding factor (i.e. graft rejection) 16. Finally, drug–drug interactions (DDI) still remain an important clinical issue in liver recipients receiving antiviral therapy, especially regarding immunosuppressive therapy. SMV has been advised against its use in patients with a cyclosporine-based immunosuppressant regimen 16. This recommendation is based on the pharmacokinetic findings of increased serum SMV levels in some patients receiving concomitant cyclosporine. The authors made no comments on this, but up to eight patients of the cohort would have been at risk of increased toxicity with this combination.

Other DAA combinations have been explored within clinical trials including liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C recurrence 17-20. Some of them, and particularly the combination of SOF/Ledipasvir (plus RBV) and SOF/Daclatasvir have shown very high efficacy (>90% SVR) and overcome some of the reported limitations of SOF/SMV (Fig. 1). Both combinations can be used safely in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and do not present meaningful interaction with the predominantly used calcineurin inhibitors.

In this same issue of Liver International, the study by Dhanasekaran et al. 21 assessed the impact of antiviral treatment on fibrosis progression in LT recipients with hepatitis C recurrence by comparing paired liver biopsies before and after treatment. Up-to-date, the effect of SVR on disease progression/regression has already been analyzed in large cohorts of immunocompetent patients, comparing pre- and post-treatment liver biopsies. The data demonstrate improvements in inflammation and fibrosis scores following SVR, although in a nonhomogeneous pattern 22. The information available in liver transplant patients is not as extensive. Studies including small cohorts of treated patients have shown a significant histological improvement or stabilization after SVR, in opposition to nonresponders 3, 4, 23. In patients who develop significant fibrosis during the first year following LT 24 fibrosis appears to be more reversible than in long-term transplant recipients with well-established fibrotic septae (which are probably more ‘resistant’ to regression) 25. The lack of a control group in most studies and the inherent limitations of liver biopsy specimens (inter- and intraobserver variability and sampling error) may explain the observed differences among some series 26.

Dhanasekaran and colleagues 21 included 116 patients who received antiviral therapy with Peg-IFN and RBV a median of 2.4 years after LT. Liver biopsies were performed by protocol at post-transplant day 7, at month 4 and yearly thereafter. Pretreatment biopsies showed that only 13.6% of patients had significant fibrosis (F2-F4) at baseline. Patients were followed up for a mean period of 7 years after treatment completion. As expected, in most nonresponders liver fibrosis progressed over time (increase of ≥1 stage in METAVIR score). Intriguingly, the authors demonstrated worsening of fibrosis in around 20% of individuals who had achieved an SVR. Among these patients, three had moderate–severe steatosis on follow-up biopsies and four showed evidence of autoimmune hepatitis. The authors hypothesize that the enhanced immune response resulting from interferon-based treatments and the loss of HCV-mediated immunosuppressive state may have an impact on the development of plasma cell hepatitis and fibrosis progression despite SVR. It is important to remember that persisting histological activity, despite biochemical remission, is frequent in patients with treated autoimmune hepatitis and is associated with lower rates of fibrosis regression and reduced long-term survival 27. The persistence of low-degree inflammation in portal tracts of patients who achieved SVR after interferon-based therapy is somewhat common in clinical practice, but most biopsies are taken shortly after treatment completion. This phenomenon may probably become less relevant when using IFN-free regimens.

A few studies have shown that the presence of different histological lesions (including chronic rejection, steatofibrosis or chronic hepatitis of undetermined aetiology) is quite common in grafts from individuals with normal liver tests (and no disease recurrence) 10 years after transplantation 28, 29. In patients without hepatitis C recurrence liver fibrosis can be found in up to 30% of grafts 10 years after transplantation, being more common in individuals who received a graft from an old donor 28. Apart from immune-mediated liver damage, it is important to exclude other risk factors such as alcohol consumption or metabolic syndrome, which could explain the presence of steatosis and fibrosis progression in some cases. Overall, the clinical relevance of these findings is uncertain, but does not seem to hamper graft survival.

In summary, in the new DAA era, we need to treat our HCV-infected transplant patients with the antiviral combination that offers the higher efficacy, better tolerability (probably without RBV?) and the lesser DDI. In this setting, SOF/SMV will be an alternative, but not the first choice because the above-mentioned limitations. Regarding the impact of virological cure on the graft, interferon-free regimens will most likely reduce or eliminate some of the immune-mediated phenomena (i.e. autoimmune hepatitis). Nevertheless, noninvasive follow-up of liver transplant recipients who achieve SVR might be informative, particularly in patients with comorbidities (metabolic syndrome, obesity) or in those with liver test abnormalities. In some cases, a liver biopsy will still be important to establish the relevance (or not) of graft damage.

Acknowledgement

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.