The Role of Profit Sharing in Dual Labour Markets with Flexible Outsourcing

Abstract

We combine profit sharing for high-skilled workers and outsourcing of low-skilled tasks in a partly imperfect dual domestic labour market, which means that only low-skilled labour is represented by a labour union. In that framework we analyse how the implementation of profit sharing for high-skilled workers influences the amount of outsourcing and the labour market outcome for low-skilled worker. By doing this, we use some specific assumptions, e.g. exponentially increasing outsourcing costs or the wage for low-skilled workers will be determined by a union whereas the wage for high-skilled workers is given. Assuming that low-skilled labour and outsourcing are interchangeable we show that profit sharing has a positive effect on the wage for low-skilled workers and helps to decrease wage dispersion. However, under these circumstances, profit sharing enhances outsourcing. Concerning the employment effects for high- and low-skilled workers, we show that there is an employment reducing effect due to higher wages for low-skilled work, which can be offset by higher productivity of highly skilled workers, as the domestic labour inputs complement each other.

1. Introduction

In an integrated world, marginal cost differences are the driving force for outsourcing. Especially for Western European firms, the possibility of reducing production costs is a main factor of outsourcing to Eastern European or Asian countries.1 Aware of this fact, many people, especially low-skilled workers, fear the consequences, i.e. the loss of employment or a wage reduction.2 However, if outsourcing leads to lower costs, the output price can fall and induce a higher product demand. This scale effect may increase labour demand and thus, the net employment effect of outsourcing is, in generally speaking, a priori ambiguous.

Due to the current interest in this topic, there is a growing amount of empirical research related to the impact of outsourcing on labour market outcomes. Most of these studies, such as Geishecker (2006) or Görg and Hanley (2005), conclude that, at least in the short run, wages and employment of low-skilled workers decline, but on the other hand, high-skilled workers benefit from outsourcing.3 In long-run analyses, for instance Amiti and Wei (2005, 2006) or Olsen et al. (2004), it has been shown that the negative short-run employment effect for low-skilled labour in one sector can be dampened or offset by increased labour demand in other sectors.

Thus, especially in the short run, the mentioned fears and worries of low-skilled workers are supported by empirics. As the public debate sees outsourcing as a short-run phenomenon, with the media and social organization such as labour unions focusing on job losses and wage decline, we will study the issue from this perspective, too. Of course, to stem these effects the structure of the low-skilled segment of the labour market, the behaviour of the firm and its incentives play an important role.

In order to avoid negative short-run consequences resulting from outsourcing, it is often argued that the domestic production has to become more attractive, i.e. lower marginal production costs or higher levels of productivity are needed. However, in Western Europe low-skilled workers are typically unionized. Therefore, the first call, i.e. lower wages, is difficult to implement for this group. Also the second postulation, higher levels of productivity, cannot be reached easily as the firm has to implement long-term instruments such as larger capital stock or on the job training programmes.

On the other hand, the remuneration for high-skilled workers affects the wage for low-skilled workers, too, and consequently the amount of outsourcing.4 For instance, higher wages for high-skilled workers increase the marginal production costs and decrease the profit, which in turn affects union behaviour and therefore outsourcing demand. Also no-cost-relevant income components for high-skilled workers such as profit sharing can affect the outsourcing decision, as it increases workers’ motivation and the degree of identification with the company, and thus stimulating the willingness to work harder, which raises the productivity.5 Resulting from a higher level of productivity, the firm's profit rises, which influences the wage for low-skilled workers and thus outsourcing. Therefore, profit sharing for high-skilled workers can reinforce or weaken the fears of low-skilled workers concerning the negative consequences of outsourcing.

The impact of profit sharing is not only interesting from an academic point of view. It is also often discussed in politics.6 In political debates it is often argued that profit sharing for managers sets the wrong incentives as their income depends on company profit. Thus, managers might be tempted to pursue a strategy of maximum short-run profit making, which is regarded as one of the reasons for the growing practice of domestic job relocation. Furthermore, it is argued that managers ignore the positive impact of social responsibility, which is a firm's distinguishing characteristic and can lead to an improved reputation and result in higher profits.

With firms, unions as well as political discussions increasingly focusing on profit sharing, the implications of bonus payments for high-skilled workers concerning outsourcing of low-skilled tasks, if firms are only profit-oriented, has to be analysed from a theoretical point of view with the intention to support or confute the public opinion at least on a firm level. Thus, our central research question is: how does the implementation of profit sharing for high-skilled workers influence outsourcing of low-skilled tasks and the labour market outcome? From our point of view, this is an important and far reaching research question, as most studies focus on the relation between outsourcing and direct wage payments only.7

If outsourcing is flexible, i.e. determined after knowing the domestic production costs, it can be used as a significant threat in the wage bargaining. Following this approach, the effects of flexible outsourcing on wage setting, is analysed. To our knowledge, Skaksen (2004) was the first to analyse this issue. As outsourcing replaces domestic labour, a higher domestic wage leads to more outsourcing. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the domestically bargained wage undoubtedly depends positively on outsourcing costs if outsourcing is used as a threat. In contrast, in case of practised outsourcing, a decrease in outsourcing costs increases the wage level. The reason for this is that the union can reap a larger share of the increased profit for the remaining employment in the non-outsourced activity. In a simple model setting, where the used production inputs are complement each other, Braun and Scheffel (2007b) analyse the impact of the domestic union wage on the number of outsourced inputs and also the impact of outsourcing costs on the wage level. Generally speaking, they find that both effects are ambiguous. A higher wage directly increases the amount of outsourcing but at the same time the overall output decreases as well, which in turn lowers the marginal benefit of outsourcing and thus leads to less imported intermediate goods. The effect of outsourcing costs can be explained in a similar way. For a given output level, an increase in outsourcing costs also increases the marginal benefit of a higher wage, which raises the wage. On the other hand, this also increases the marginal costs for the firm. Due to a lower output demand, the marginal benefit of a higher wage declines, which lowers the wage level.

However, these analyses do not focus on the relation of non-cost-relevant income components and outsourcing. Filling this gap, König and Koskela (2012) analyse the impact of profit sharing on the labour market outcome if unionized low-skilled workers participate in it. They find that, in general, the effects of the bonus payment on the wage and therefore on outsourcing and domestic labour are ambiguous. Thus, their research question is similar to the one of the present paper. However, the central difference is that they abstract from a heterogeneous labour force.8 This fact allows us to implement the usual observation that profit sharing is part of the remuneration scheme for high-skilled workers. Due to this more realistic specification, we identify the impact of the paying system for a group of workers, which is not directly affected by outsourcing, on the labour market outcome for low-skilled workers, which are threatened by outsourcing, and consequently, for the size of external procurement itself. Thus, we focus on the interaction of profit sharing for high-skilled workers and outsourcing of low-skilled tasks.

In this paper, we combine the research concerning effects of outsourcing in an imperfect labour market and profit sharing for high-skilled workers with individual effort determination. We analyse the interaction of outsourcing and profit sharing in a partial equilibrium model,9 in which we assume that low-skilled workers are unionized, whereas high-skilled workers are not unionized and whose wages are given. Furthermore, we assume that profit sharing is a commitment and therefore an optional offer, which is set by a firm or exogenously imposed.10 In this specification, we find that profit participation has an individual effort augmenting effect for high-skilled workers and increases labour demand for this kind of labour. Due to the complementary relation between different kinds of labour, the labour union can demand a higher wage for low-skilled workers. Thus, for a constant wage level for high-skilled workers, profit sharing leads to lower wage dispersion in a firm. As profit sharing increases the low-skilled wage and therefore marginal domestic costs, it indirectly enhances outsourcing activities. Concerning the fear of unemployment, we found that the employment effects of profit sharing for both types of labour are ambiguous. On the one hand, there is a labour augmenting effect via higher effort of high-skilled workers. But on the other hand there is a labour reducing effect due to the induced increase of the wage for low-skilled workers.

We proceed as follows. Section 2 presents the framework and investigates the model in terms of labour and outsourcing demand as well as employee effort. Section 3 concentrates on low-skilled wage formation and the overall employment effects. Finally, Section 4 concludes briefly and presents a short discussion of the influence of our assumptions.

2. Basic framework

Using a model with heterogeneous domestic workers, i.e. a dual domestic labour market, we analyse the relation between flexible international outsourcing of low-skilled tasks and committed profit sharing for high-skilled workers. In our model, production uses effective high-skilled worker services and unskilled worker services. As effective skilled employment we see a combination of absolute skilled employment and the workers’ provided effort. In line with empirical studies by Munch and Skaksen (2009), we assume that low-skilled workers and outsourcing activities are substitutes. Consequently, low-skilled labour services can be either provided by a firm's own workers or obtained from abroad by way of international outsourcing. It is reasonable to assume that the outsourced inputs are produced by low-skilled workers and therefore these tasks can be characterized as standard components. Following this argumentation, it can be supposed that the firm is flexible enough to decide on the amount of outsourcing after the domestic low-skilled wage determination as no strategic partnership or special requirements for these goods are necessary.11

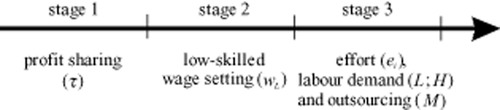

Summarizing the described specification, the time sequence of the decisions is illustrated in Figure 1.

Sequence of events

Note that the small firm takes the market wage for high-skilled workers as given. As represented in Figure 1, the firm commits to profit sharing before the wage negotiation for low-skilled workers, as it is a voluntary offer by the firm.12 When the earnings components are known, the representative high-skilled worker decides on effort provision. Therefore, the structure of actions can be interpreted as sequential decisions on three stages. Decisions are analysed by using backward induction.

Of course, our assumptions are specific, as one could also imagine that the labour union represents both types of workers. Also profit sharing could be a result of the bargaining or be shared with all employees.

Additionally, one could assume that effort is decided at a fourth stage. Although our timing decisions capture the idea that high-skilled workers and the firm take each other's decisions as given, the effort choice at the fourth stage means that the firm anticipates its effect on effort. Our structure can be justified by the fact that the firm cannot observe effort and the behaviour of high-skilled workers but the high-skilled employees can supervise each other. Therefore, it is reasonable to ignore the firm's impact on effort provision, which equals the simultaneous determination of labour demand and effort presented at stage 3.

As we focus only on the question if the profit dependence of the high-skilled workers’ income is a reason for more outsourcing of low-skilled tasks, we keep the analysis simple and neglect all of the modifications mentioned above. However, in our final conclusions we discuss which effects the relaxing of some of our restrictions have.

2.1 Labour and outsourcing demand

. So, the impact of the provision of an additional unit of effort by a single high-skilled worker is

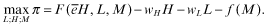

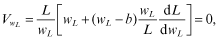

. So, the impact of the provision of an additional unit of effort by a single high-skilled worker is  .14 Algebraically the firm calculus is:

.14 Algebraically the firm calculus is:

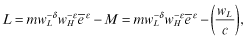

(1)

(1)In order to obtain M units of outsourced low-skilled labour input, we assume that the firm has to spend f(M) = 0.5cM2. At first glance, building an outsourcing network seems to produce some fixed costs. But as soon as the network has been established the marginal costs remain constant or are decreasing. However, one can divide the outsourcing process into different steps. Every step will be outsourced separately. In that case, every newly established outsourcing contract will create new and rising fixed costs. Thus, the overall outsourcing costs can be seen as a kind of increasing step function and approximately described by a convex function even though the marginal unit costs of outsourcing are constant. For the sake of simplification we model this convex cost function as a quadratic cost function.16 An alternative explanation would be to assume that there are other costs associated with outsourcing, such as the price. These could be transport costs, which are exponentially increasing with higher outsourcing. In that case our quadratic approach can be interpreted in line with the Krugman version of iceberg transportation cost functions. This interpretation implies that the costs of goods increase exponentially with the distance, with the cost function incorporating all forms of distance-transactions and trade costs. Thus, in our framework, the firm would buy the inputs from different suppliers at different locations and therefore transport parts and goods over different distances.17

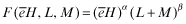

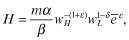

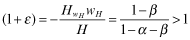

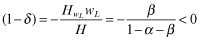

For an explicit solution of our model we assume a Cobb–Douglas production function with decreasing returns to scale according to three inputs, i.e.  , where the parameters α and β are assumed to satisfy the assumptions α, β > 0 and 1 − α − β > 0. From the production function, we can derive the marginal products of skilled and unskilled labour and outsourcing, i.e. FH > 0 and FL = FM > 0. For the cross derivatives we have FHL = FHM > 0 and FLM < 0. Taking these derivatives, we can conclude that the domestic skilled labour input and the outsourced or domestic unskilled labour input complement each other, whereas the unskilled domestic labour input and the outsourced tasks are interchangeable.

, where the parameters α and β are assumed to satisfy the assumptions α, β > 0 and 1 − α − β > 0. From the production function, we can derive the marginal products of skilled and unskilled labour and outsourcing, i.e. FH > 0 and FL = FM > 0. For the cross derivatives we have FHL = FHM > 0 and FLM < 0. Taking these derivatives, we can conclude that the domestic skilled labour input and the outsourced or domestic unskilled labour input complement each other, whereas the unskilled domestic labour input and the outsourced tasks are interchangeable.

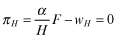

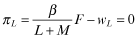

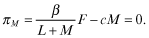

(2a)

(2a) (2b)

(2b) (2c)

(2c) (3)

(3) (4)

(4) . According to equation 4, higher domestic wage level for unskilled workers and lower outsourcing costs will increase outsourcing. Substituting 3 into the production function by using 2b yields the unskilled labour demand:

. According to equation 4, higher domestic wage level for unskilled workers and lower outsourcing costs will increase outsourcing. Substituting 3 into the production function by using 2b yields the unskilled labour demand:

(5)

(5) , and

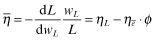

, and  . According to 4 and 5, a higher wage for low-skilled workers leads to more outsourcing activities and decreases low-skilled labour demand. Also, higher cross wage and lower effort reduce the low-skilled labour demand.

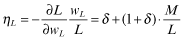

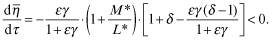

. According to 4 and 5, a higher wage for low-skilled workers leads to more outsourcing activities and decreases low-skilled labour demand. Also, higher cross wage and lower effort reduce the low-skilled labour demand. (6a)

(6a) (6b)

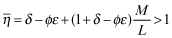

(6b)In the absence of outsourcing, the wage and effort elasticities are constant, which is driven by the use of a Cobb–Douglas production function and the assumption of constant input prices, i.e. ηL|M=0 = δ and  . As one can also see, in the absence of outsourcing elasticities are smaller. This results from the fact that outsourcing reduces the absolute value of labour demand, whereas the effect of effort equals the effect of wage for high-skilled workers, whether there is outsourcing or not.

. As one can also see, in the absence of outsourcing elasticities are smaller. This results from the fact that outsourcing reduces the absolute value of labour demand, whereas the effect of effort equals the effect of wage for high-skilled workers, whether there is outsourcing or not.

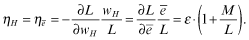

(7)

(7) and

and  . As one can see, these elasticities are constant, which is the result of our specification. Thus, changes in wages affect the high-skilled labour demand only via an adoption of the optimal output level.

. As one can see, these elasticities are constant, which is the result of our specification. Thus, changes in wages affect the high-skilled labour demand only via an adoption of the optimal output level.2.2 Effort formation and direct employment effects for high-skilled workers

2.2.1 Effort determination of high-skilled workers

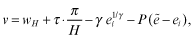

For the utility of a high-skilled individual, we assume that the utility function is additively separable and depends positively on income and negatively on disutility of effort. This disutility is described by  with 0 < γ < 1. In addition to the disutility of effort also peer pressure negatively affects individual utility, which results from the fact that employees can observe each other. Peer pressure depends on the difference between the social norm and the individually provided level of effort, i.e.

with 0 < γ < 1. In addition to the disutility of effort also peer pressure negatively affects individual utility, which results from the fact that employees can observe each other. Peer pressure depends on the difference between the social norm and the individually provided level of effort, i.e.  , where

, where  is the social norm defined as the average effort of all workers other than i.18

is the social norm defined as the average effort of all workers other than i.18

. The idea behind this formulation is that high-skilled workers are assumed to work in a team, with the whole team receiving the profit income τ · π, which is distributed equally among the team members. Using these assumptions, we can formalize the utility function for an employed worker in a profit sharing firm in 8a and for an employed worker in a firm with no profit sharing in 8b:

. The idea behind this formulation is that high-skilled workers are assumed to work in a team, with the whole team receiving the profit income τ · π, which is distributed equally among the team members. Using these assumptions, we can formalize the utility function for an employed worker in a profit sharing firm in 8a and for an employed worker in a firm with no profit sharing in 8b:

(8a)

(8a) (8b)

(8b)As one can see, the outside option of high-skilled workers is the market wage wH, which is fixed from a small firm's perspective. Therefore, high-skilled workers are paid the same wage everywhere. However, skilled jobs are different with respect to their job characteristics concerning the existence of a profit sharing system.19

- A 1: Low-skilled and outsourcing activities are substitutes, whereas high-skilled labour and outsourcing complement each other.

- A 2: Outsourcing costs increase exponentially.

- A 3: High-skilled workers individually determine their effort.

- A 4: Only low-skilled labour is unionized, whereas the wage for the high-skilled workers is exogenous and fixed.

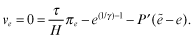

A high-skilled worker's problem is to choose the level of individual effort to maximize its utility. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that every group member can at no charge verify the effort of the others, but the firm owner cannot do this. Furthermore, we assume Nash-behaviour, where every worker chooses his/her effort, taking the effort of others as given. Thus, the social norm is not affected by individual effort, i.e.  (see Lin et al., 2002).

(see Lin et al., 2002).

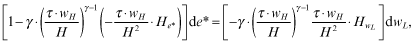

(9)

(9) . Assuming Nash-behaviour and that any deviation from the group norm yields the same disutility, we find that in the symmetric equilibrium the individual effort level equals the group norm, i.e.

. Assuming Nash-behaviour and that any deviation from the group norm yields the same disutility, we find that in the symmetric equilibrium the individual effort level equals the group norm, i.e.  and

and  .21 As one can see from equation 9, in that case, the provided level of effort equals the effort level, which would be chosen without any peer pressure. Thus, peer pressure as a result of observation ensures that optimal individual effort will be provided and zero effort does not result. Solving the first-order condition 9, we obtain:

.21 As one can see from equation 9, in that case, the provided level of effort equals the effort level, which would be chosen without any peer pressure. Thus, peer pressure as a result of observation ensures that optimal individual effort will be provided and zero effort does not result. Solving the first-order condition 9, we obtain:

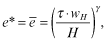

(10)

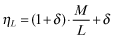

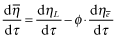

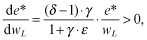

(10)As alterations of the wage for low-skilled workers and profit sharing affect all skilled workers, each skilled worker will adjust his/her effort accordingly. We derive these effects by taking the differential of effort function 10. Here, we find  and de*/dτ > 0 (see Appendix A), so that the wage for low-skilled workers and profit sharing enhance productivity by increasing effort provision and positively, but indirectly, affecting labour demand. All this is in line with previous empiric findings.22 As a higher wage for low-skilled workers reduces low-skilled employment due to the complementary relation between the two types of labour, high-skilled employment also decreases. However, decreasing high-skilled employment makes effort provision of employed skilled workers rise. This is due to the fact that now the profit is shared among a smaller group, which increases individual revenues for higher levels of effort and consequently workers provide more effort.

and de*/dτ > 0 (see Appendix A), so that the wage for low-skilled workers and profit sharing enhance productivity by increasing effort provision and positively, but indirectly, affecting labour demand. All this is in line with previous empiric findings.22 As a higher wage for low-skilled workers reduces low-skilled employment due to the complementary relation between the two types of labour, high-skilled employment also decreases. However, decreasing high-skilled employment makes effort provision of employed skilled workers rise. This is due to the fact that now the profit is shared among a smaller group, which increases individual revenues for higher levels of effort and consequently workers provide more effort.

At this point we can summarize our findings as follows.

Proposition 1.In the presence of flexible outsourcing and under the assumptions A1–A4, profit sharing and the wage for low-skilled workers have an individually effort augmenting effect and thus increase productivity.

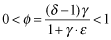

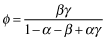

For the next analysis, the effort elasticity of the wage for low-skilled workers is important. In our framework, we find that  , where 0 < ϕ < 1 (see Appendix A). This means that the low-skilled wage setting by the labour union is binding.

, where 0 < ϕ < 1 (see Appendix A). This means that the low-skilled wage setting by the labour union is binding.

The effect of the wage for high-skilled workers on effort provision can be illustrated, too. Here, we obtain the intuitive result that  , as a higher wage reduces the group size and increases the return of effort, which serves as an incentive for providing more effort.

, as a higher wage reduces the group size and increases the return of effort, which serves as an incentive for providing more effort.

A special feature is to examine the effort elasticity in terms of the wage for high-skilled workers to study whether the well-known Solow-condition is valid or not. Using our results, we find  , so that the high-skilled wage elasticity of effort equals only one, if γ = 1/2.23 Ensuring a binding market-clearing wage for high-skilled workers, we have to assume that γ < 1/2. Thus, the classic efficiency wage argument does not hold in our framework.

, so that the high-skilled wage elasticity of effort equals only one, if γ = 1/2.23 Ensuring a binding market-clearing wage for high-skilled workers, we have to assume that γ < 1/2. Thus, the classic efficiency wage argument does not hold in our framework.

2.2.2 Direct employment effects for high-skilled workers

As we assume a constant wage for skilled workers wH, the employment of high-skilled workers is described by equation 7. Thus, we can determine the direct employment effects of the wage for low-skilled workers and profit sharing by taking into account the effects of effort provision. This means, we show the impact of both parameters on stage 3, where the firm and the high-skilled workers correctly anticipate each other's reactions.

. This can be solved to (for the sign see Appendix A):

. This can be solved to (for the sign see Appendix A):

(11)

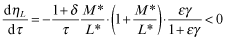

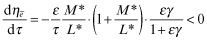

(11)So there is a negative relation between the wage for low-skilled workers and the employment of high-skilled workers with the complementary effect dominating the effort effect. Thus, the induced effort effect can dampen the negative wage effect but cannot invert it.

As we know, a higher wage for low-skilled workers leads to higher effort via an increased individual return due to decreasing high-skilled employment. If a positive effect of the wage for low-skilled workers on high-skilled demand existed, this would coincide with a negative effect of the wage for low-skilled workers on effort. Thus, the effort effect will be induced by changing the number of high-skilled employees and goes in the opposite direction as the direct impact of the wage for low-skilled workers on labour demand. As the impact on effort is a second-order effect, in our framework, the effort effect cannot be the dominating effect.

(12)

(12)We can now summarize our findings regarding the properties of skilled employment in the presence of outsourcing as follows.

Proposition 2.In the presence of flexible outsourcing and under our assumptions A1–A4:

- (a) a higher wage for low-skilled workers reduces skilled employment, and

- (b) profit sharing via higher level of effort has a positive impact on high-skilled labour demand.

These results are intuitive in our setting. A higher wage for low-skilled workers affects high-skilled labour demand in two ways. First, there is the negative direct effect, which leads to lower high-skilled demand resulting from the complementary relation of the types of labour. However, this increases effort, which raises high-skilled labour demand. This describes the second way, which is referred to as a positive indirect effect.

The positive indirect effect of profit sharing can be explained as follows. Higher profit sharing increases effort, which for a given wage level leads to higher productivity and increases high-skilled labour demand. Of course, if profit sharing also affects the wage for low-skilled workers, then this effect can be strengthened or weakened.

3. Low-skilled wage formation

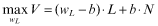

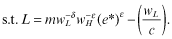

In the formation, the wage level for low-skilled workers in anticipation of an optimal in-house labour demand, outsourcing and high-skilled effort will be determined.

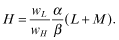

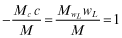

(13)

(13)

(14)

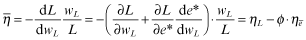

(14) . Using this and solving equation 14 we obtain the well-known standard result for the optimal wage level:

. Using this and solving equation 14 we obtain the well-known standard result for the optimal wage level:

(15)

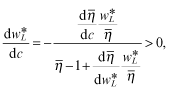

(15) (see Appendix B).

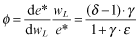

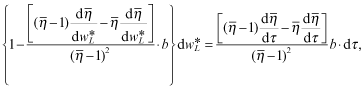

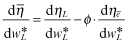

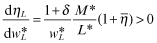

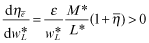

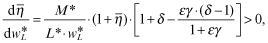

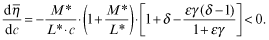

(see Appendix B). (16)

(16) (17)

(17) ,

,  , and

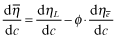

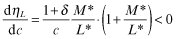

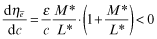

, and  . Therefore, a higher wage for low-skilled workers increases whereas higher outsourcing costs and profit sharing decrease the total wage elasticity of domestic low-skilled labour demand.25

. Therefore, a higher wage for low-skilled workers increases whereas higher outsourcing costs and profit sharing decrease the total wage elasticity of domestic low-skilled labour demand.25The reasons for the findings concerning the impact of profit sharing and outsourcing costs on the bargained wage level are quite obvious. The effect of profit sharing is driven by the fact that high-skilled demand increases with higher profit participation. Due to the complementary relation, also low-skilled demand increases, which weakens the bargaining position of the firm. Furthermore, higher outsourcing costs weaken the firm's bargaining position because the incentive for substituting domestic low-skilled labour decreases. Thus, in both cases the firm's bargaining position grows worse and the labour demand becomes less sensitive to a higher wage for low-skilled workers. Therefore, profit sharing and outsourcing costs raise the wage for low-skilled workers.

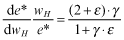

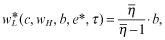

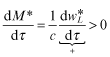

(18)

(18)We can summarize our findings concerning the effects of outsourcing costs and profit sharing on the wage for low-skilled workers, respectively the impact of profit sharing on outsourcing as follows.

Proposition 3.In the presence of flexible outsourcing and under our assumptions A1–A4:

- (a) higher level of profit sharing for skilled workers has a positive effect on the wage for low-skilled workers and thus indirectly enhances outsourcing, whereas

- (b) higher costs of outsourcing increase the wage for low-skilled labour.

Higher profit sharing increases effort and the skilled labour demand. As labour inputs complement each other, the low-skilled labour demand increases as well. Thus, the union's marginal costs of increasing wages are smaller due to fewer dismissals and the union can demand a higher wage. However, the wage enhancing effect intensifies outsourcing demand, which results from the substitutability of domestic low-skilled labour tasks and foreign intermediate goods.

Higher outsourcing costs mean lower outsourcing demand for a given wage level for low-skilled workers. As this limit the opportunities of a firm to substitute domestic low-skilled tasks by outsourcing, the firm seems likely to react less sensitively to an increase of the wage for low-skilled workers, which corresponds with a less elastic low-skilled labour demand. Due to this fact, the union's marginal costs of a higher wage decrease and therefore higher outsourcing costs induce a more aggressive wage setting.26

Due to the assumption that the wage for high-skilled workers is the exogenous market wage and thus a fixed income component from the firms’ point of view, we can also look at the relation between the wage levels and thus at the impact of profit sharing concerning wage dispersion in a firm.27 As it is reasonable to assume that  , where wH is constant from a single firm's view, we can conclude in the following way.

, where wH is constant from a single firm's view, we can conclude in the following way.

Corollary 1.Under our assumptions A1–A4, more profit sharing for high-skilled workers decreases wage dispersion in a firm because the wage for low-skilled workers rises.

This is an interesting feature. Due to the substitutability of domestic low-skilled tasks and foreign intermediate goods, one would expect that the possibility of outsourcing leads to higher wage dispersion because low-skilled workers get into wage pressure. Our analysis shows that introducing profit sharing increases the wage for low-skilled workers, as the union can act more aggressively due to the labour-augmenting effort effect. If we take a small single firm and given wage level for high-skilled workers, then profit sharing leads to a lower wage gap in that firm and counteracts the wage pressure of flexible outsourcing.

It should be mentioned that any improvement of the low-skilled workers’ bargaining power, such as stricter laws or tightness of high-skilled workers, leads to a higher wage for low-skilled workers, as there are limited quantities of substitutability of low-skilled labour and outsourcing. This, is demonstrated in equation 4, where one unit of wage increase raises the amount of outsourcing only by 1/c.

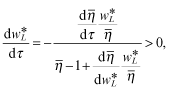

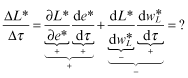

(19)

(19)The first term in equation 19 describes the positive effect of profit sharing on low-skilled labour demand. As shown earlier, higher profit sharing intensifies effort leading to an increase in high-skilled labour employment and, due to the complementarity of inputs, also to an increase in low-skilled labour demand. The second term describes the negative effect of profit sharing on the low-skilled labour demand. Higher profit sharing provides opportunity for the labour union to set a higher wage. This results in more outsourcing and less low-skilled employment. Thus, we have two opposing effects, where the overall effect is a priori ambiguous.

(20)

(20)From equation 20, we see that higher profit sharing also has an ambiguous overall effect on high-skilled employment. The first term, which corresponds with the effect presented in equation 12, describes the known enhancing employment effect via effort provision. The second term describes the negative effect from the change of the wage level for low-skilled workers, which induces a lower unskilled labour demand. Due to the complementarity of the types of labour, also high-skilled labour demand decreases. Therefore, the high-skilled employment effect also consists of two opposing effects.

Proposition 4.In the presence of flexible outsourcing and under our assumptions A1–A4, profit sharing may have an augmenting effect on low-skilled and high-skilled employment.

As our previous results point out, it is possible that implementing a profit sharing scheme for high-skilled workers decreases the wage gap in a firm without losing low-skilled employment. However, this only occurs if the induced substitution effect of a higher wage for low-skilled workers can be offset by the effort effect. Thus, despite an increased outsourcing demand, profit sharing can also create higher employment. As bonus payments for high-skilled workers do not necessarily lead to lower employment of low-skilled and high-skilled workers, such compensation schemes are not be as bad as publically seen.

Although the public debate is dominated by the impacts of profit sharing for managers on the wage for low-skilled workers and the low-skilled employment level another interesting point should be mentioned. We know that profit sharing stimulates effort, which results in a higher wage for low-skilled workers, whereas the overall employment effect is ambiguous. As the surplus of low-skilled workers depends on their wage and employment level, one would expect that the effect of profit sharing on the surplus is ambiguous as well. A thought scenario shows that this is not the case. Imagine a situation in which the union chooses the same wage level for low-skilled workers. Thus, there is no negative employment effect via the wage channel and the amount of outsourcing is not affected, either. In contrast, due to higher effort and the complementarity of labour inputs, low-skilled employment increases and so does the surplus. Even if the wage increases, profit sharing undoubtedly does not decrease the surplus. This is due to the fact that the union maximizes the surplus and does not choose the alternative of a constant wage. Thus, the higher wage level compensates at least the possible negative employment effect.

4. Concluding remarks and discussion

In this paper, we tried to describe a framework of flexible outsourcing in a partly unionized dual labour market. In Western European countries, we often observe that low-skilled workers are organized in labour unions and thus their wages are determined by bargaining between firms or employer federations and trade unions. In contrast, wages for high-skilled workers are mostly determined competitively. However, at the same time high-skilled workers often also directly participate in a firm's success via profit sharing, which also affects wage determination of low-skilled labour as well as the amount of outsourcing. As especially low-skilled workers fear the consequences of international outsourcing, i.e. lower wages and lay-offs, we focus on the effects of profit-based remuneration parts for high-skilled workers on the labour market outcome of low-skilled workers.

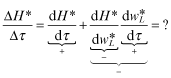

In our analysis, we showed that the wage of low-skilled workers is positively affected by outsourcing costs and profit sharing for high-skilled workers. Because the wage for high-skilled workers is constant and usually higher than the wage for low-skilled workers, higher outsourcing costs and profit sharing reduce wage dispersion in a single firm. Also, we find that the effect of profit sharing on outsourcing activities is indirectly negative via the induced change of the wage for low-skilled workers. Finally, we characterized the employment effects of profit sharing. Here we find that profit sharing stimulates low-skilled and high-skilled labour demand via increased effort. However, on the other hand it decreases labour demand for both types via the higher wage for low-skilled workers. Thus, the overall employment effects are ambiguous. In what follows, under certain circumstances, bonus payments for high-skilled workers help to realize the aims of adequate wage and high employment levels for low-skilled workers in a firm. Therefore, they can weaken the negative labour market consequences of outsourcing for low-skilled workers.

Overall, it should not been forgotten that the derived results crucially depend on the assumptions we made. For instance, constant outsourcing costs combined with perfect substitutability of outsourcing and the employment of low-skilled workers do not lead to the result that higher profit sharing increases the wage for low-skilled workers, as there would be either only domestic employment or outsourcing if wL < c respectively wL > c. Thus, as far as labour unions are concerned it becomes beneficial to set wL ≤ c if outsourcing costs are higher than the outside option of low-skilled workers, whereas in case of wL = c the wage will stay constant.

The bargaining process can also be modelled in a different way. One possibility is to assume that the low-skilled employment level will be determined by bargaining, too. Here, the wage would decrease to its lowest possible level, which could be the domestic unemployment benefit or the outsourcing costs. Thus, profit sharing would also lose its wage increasing effect.

As a third example, the relation between labour inputs can also be relaxed. If high- and low-skilled workers are substitutes, higher managerial effort induced by profit sharing does not lead to a higher wage for low-skilled workers.

One of our most restrictive assumptions is the exogenous wage for high-skilled workers, which can be regarded as a kind of minimum wage. However, the implementation of an endogenous wage determination for high-skilled workers in our representative firm would have implications for the high-skilled labour market. In a perfect labour market, where high-skilled workers are mobile, every firm pays the same wage. However, if the firms offer different levels of profit sharing the wages can differ. The reason is that workers compare their incomes, consisting of the wage payment and the profit income or only of the wage. Thus, a profit sharing firm can decrease its wage level, whereas the participation constraint and the income of high-skilled workers remain untouched. However, this affects the demand side and therefore the employment level of low- and high-skilled workers. Needless to say that it also affects the union's wage setting for low-skilled workers. Finally, if there is profit sharing only in some but not all firms, there are different wage levels for high-skilled workers in the equilibrium. Yet the income level of high-skilled workers is the same. To be more precise, firms with a profit sharing system pay lower wages than firms without one. Of course, to show this effect we have to adapt our set up. First, we have to model a second firm or sector. Second, we have to implement the labour supply of high-skilled labour in both sectors. Although implementing an endogenous wage determination for high-skilled workers would be more realistic and open more working channels, it would go beyond the scope of our research question, where we focus on the relationship of outsourcing and profit sharing. For that and for keeping the analysis simple, we neglect an endogenous wage setting for high-skilled. Thus, our assumption of an exogenous and given wage level for high-skilled workers is a simplification for the analysis of the interaction between outsourcing and profit sharing for high-skilled workers.

The discussion showed that our analysis can only be seen as a first step to evaluate the relation between bonus payments and outsourcing. An interesting and necessary topic for further research is the specification of the wage for high-skilled workers, which incorporates more working channels of profit sharing on outsourcing. As described above, this can be done by assuming a competitive labour market with an explicit labour supply function or by modelling unionized high-skilled workers. Here, assumptions can vary. There may be two independent labour unions or only one labour union representing both types of labour. However, to be more precise, these questions should be analysed in depth in a more comprehensive setting.

Notes

is the total actual working-time.

is the total actual working-time.Appendix A: Comparative statics of effort effects

(A1)

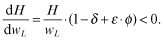

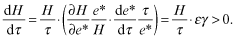

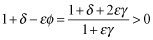

(A1)For the effort elasticity with respect to the low-skilled wage we have  . This holds as we rewrite this term to

. This holds as we rewrite this term to  . Because our assumptions 1 − α − β > 0, α; β > 0 and γ ∈ (0; 1) we have ϕ ∈ (0; 1). For the high-skilled employment effect of higher low-skilled wage, we need the sign of 1 − δ + ε · ϕ. Using our results for ϕ we can rewrite this term to

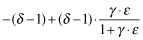

. Because our assumptions 1 − α − β > 0, α; β > 0 and γ ∈ (0; 1) we have ϕ ∈ (0; 1). For the high-skilled employment effect of higher low-skilled wage, we need the sign of 1 − δ + ε · ϕ. Using our results for ϕ we can rewrite this term to  , which leads to

, which leads to  .

.

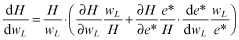

Appendix B: Effects of parameters on low-skilled wage

The total wage elasticity of low-skilled labour demand is  , as δ > ϕε and therefore also 1 + δ − ϕε > 0.

, as δ > ϕε and therefore also 1 + δ − ϕε > 0.

expressed as equation 16. Similarly, we can determine the effect of outsourcing costs on the bargained wage.

expressed as equation 16. Similarly, we can determine the effect of outsourcing costs on the bargained wage. , where

, where  ,

,  and

and  . Thus, differentiating

. Thus, differentiating  with respect to

with respect to  gives

gives  , where

, where  and

and  . Simplifying yields:

. Simplifying yields:

(B1)

(B1) .

. , with

, with  and

and  , which leads to:

, which leads to:

(B2)

(B2) with

with  and

and  , we have the following:

, we have the following:

(B3)

(B3)

and

and  so that we can simplify

so that we can simplify

.

.