For Better, For Worse: Manatee-Associated Tursiocola (Bacillariophyta) Remain Faithful to Their Host

Abstract

With the advent of more comprehensive research into the microbiome and interactions between animals and their microbiota, new solutions can be applied to address conservation challenges such as husbandry and medical care of captive animals. Although studies on epizoic algae are relatively rare, and the function and role of those mainly photosynthetic organisms in the animal microbiome is not well understood, recent surveys on epizoic diatoms show that some of them exhibit traits of obligate epibionts. This study explores diatom communities on captive–born manatees from the Africarium in Wroclaw, Poland. Light and scanning electron microscopy analyses revealed that skin of all animals sampled was dominated by apochlorotic Tursiocola cf. ziemanii, an epizoic species described recently from Florida manatees, that reached 99,9% of the total diatom abundance. Despite using media with a wide range of salinity (0–34), the isolated Tursiocola cells did not grow, whereas the normally pigmented Planothidium sp., that was only occasionally found on the animal substratum, survived in all culture media tested. Our observations provide direct evidence that manatee–associated Tursiocola endure the dramatic salinity changes that occur regularly during their host life cycle, and can thrive in an artificial captive setting, if the manatee substratum is available. The impact of practices and routines used by the Africarium on manatee–associated diatoms, as well as ultrastructure of areolae in Tursiocola, are briefly discussed.

Studies of endo- and epi-biotic microbial communities show that microbiome research may provide valuable insights into animal health and behavior. The growing understanding of the microbiome composition and function changes how various diseases and disorders are perceived. In many cases, the origin of illness is not necessarily linked to the presence of pathogens, but rather the lack of some of the native microbiome components (Redford et al. 2012). Although this view becomes increasingly relevant in the context of the biodiversity crisis and environmental protection, little has been done to implement the recent developments and ideas to improve the overall condition and well-being of captive animals.

Photosynthetic organisms or microalgae, such as diatoms, are rarely considered as essential elements of any animal microbiome. Yet there is consistent evidence that some diatom species are highly specialized and adapted to the epizoic lifestyle, and their survival may depend on the survival of their hosts (Holmes et al. 1993, Majewska et al. 2015, Robinson et al. 2016, Frankovich et al. 2018). This is plausible as specific ecological preferences of many diatom species, as well as their inability to exist in non-preferred habitats where they are outcompeted by more tolerant and better–adapted taxa, are well known and have long been used in various biomonitoring applications (Smol 1990, Round 1991, Desrosiers et al. 2013). Thus, truly epizoic diatom species would represent yet another group of stenotopic organisms and potential bioindicators.

As diatom biofilm on the animal skin or carapace may reach very high densities (Holmes et al. 1993, Majewska et al. 2015), it is conceivable that the diatom presence would not be insignificant for the other animal–associated microorganisms and possibly the animal host itself. For example, although microscopic diatoms should not significantly increase the animal weight and drag, which would increase the energetic cost of swimming and diving, they may facilitate attachment of larger organisms through biochemical conditioning of the immersed surface (Wahl 1989). On the other hand, skin–associated diatoms may increase aquatic cutaneous respiration rates in marine reptiles (Graham 1974) or provide protection against the excessive UV radiation through both the UV–absorbing compounds produced by the diatom cell and the unique nanostructure of the frustule (Ellegaard et al. 2016). Moreover, production of antibacterial, antifungal, and other biologically active compounds has been detected in numerous diatom species (Lincoln et al. 1990). It cannot be excluded that similar compounds from truly epizoic diatoms may target host species–specific pathogens competing with non-pathogenic microalgae and the inhabitants of their phycosphere (Ashworth and Morris 2016) for suitable adhesion sites on the animal surface.

In this study, we examined diatom microflora growing on the skin of captive West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus). The West Indian manatee is one of the four extant species in the order Sirenia. All sirenians are currently endangered and threatened by anthropogenic disturbances including coastal urbanization, habitat fragmentation, fishing, and pollution. In the future, captive breeding and reintroduction programmes may improve their potential of survival in the wild (Flint and Bonde 2017). Therefore, knowledge about the manatee microbiome may have a significant contribution to the success of these endeavors.

Materials and Methods

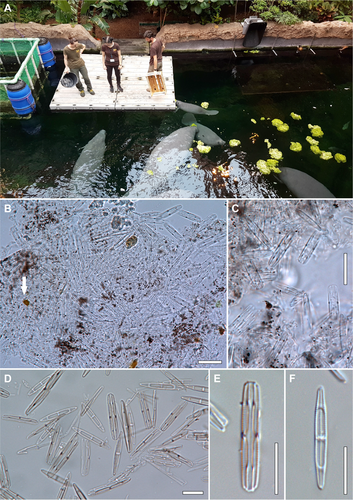

Diatom samples were collected from five out of six manatees kept in the Africarium, Wroclaw Zoo, Wroclaw, Poland, on September 12, 2019. These included two females born in the Singapore Zoological Gardens, Singapore, two males born in Odense Zoo, Denmark, and a juvenile born in the Africarium (Wroclaw, Poland; Table 1, Fig. 1A). A particularly skittish 3-month-old individual named “Piraja” was not sampled as to not agitate and discomfort the very young animal. During the relocation to the Africarium, the Odense animals were transported in containers partially filled with water, while the Singaporean manatees travelled in empty wooden chests and were watered once per hour. Only two out of thirteen animals from Odense Zoo and the Singapore Zoological Gardens that shared the enclosure with the Africarium manatees before their arrival to Wroclaw were born and captured in the wild (Guyana; Tables 2 and 3).

| Name | ID | Sex | Birth date | Birth location | Relocation date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel | 217229 | Female | Feb 21, 2013 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | Sept. 6, 2017 |

| Armstrong | 214332 | Male | June 28, 2009 | Odense Zoo, Odense, Denmark | Oct 1, 2014 |

| Gumle | 214348 | Male | June 28, 2009 | Odense Zoo, Odense, Denmark | Oct 3, 2014 |

| Lavia | 218054 | Female | March 3, 2018 | Wroclaw Zoo, Wroclaw, Poland | – |

| Ling | 217228 | Female | July 7, 2006 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | Sept 6, 2017 |

| Pirajaa | 219194 | Female | June 8, 2019 | Wroclaw Zoo, Wroclaw, Poland | – |

- a Not sampled.

| Name | ID | Sex | Birth date | Birth location | Relocation date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canola | G13916 | Female | Aug 6, 2014 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

| Eva | G2564 | Female | Apr 13, 1991 | Nuremberg Zoo, Nuremberg, Germany | May 15, 1994 |

| Fritz | G2563 | Male | July 27, 1979 | Nuremberg Zoo, Nuremberg, Germany | May 15, 1994 |

| Indy | G10167 | Female | Oct 10, 2004 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

| Isa | G11312 | Female | Nov 24, 2008 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | - |

| Joella | G14816 | Female | Apr 10, 2016 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

| Kaiser | G15288 | Male | March 28, 2017 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

| Sundae | G13273 | Male | May 19, 2013 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

| Turbo | G4231 | Male | Apr 27, 1986 | Nuremberg Zoo, Nuremberg, Germany | July 26, 1996a |

| Willy | G14225 | Male | Oct 7, 2015 | Singapore Zoological Gardens, Mandai, Singapore | – |

- a Relocated to Royal Burgers’ Zoo, Arnhem, The Netherlands on July 12, 1989.

| Name | ID | Sex | Birth date | Birth location | Relocation date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femmer | MAN4 | Female | ~1993–1994 | Guyanaa | Nov 23, 2001 |

| Frodo | MAN3 | Male | ~1996–1997 | Guyanaa | Nov 23, 2001 |

| Henriette | MAN1 | Female | Dec 25, 1991 | ARTIS Amsterdam Royal Zoo, Amsterdam, The Netherlands | Mar 23, 2001b |

- a Wild-born, captured by Guyana Zoological Park, Georgetown, Guyana.

- b Relocated to Nuremberg Zoo, Nuremberg, Germany on May 25, 1994.

The Africarium manatees are kept in a 1,250 m3 concrete enclosure coated with polyurea and filled with freshwater maintained at 26–28°C by a titanium heat exchanger. Prior to its discharge into the enclosure, the water is pumped through the filtration system composed of drum filters with a series of sieves no. 18 (mesh size; first stage of the mechanical treatment) and a sand pressure filter (second stage of the mechanical treatment). In between the two stages, an acidity corrector (HCl), as well as an aluminium hydroxide–based coagulant, are added. Subsequently, the water is disinfected with a UV dose of 60 mJ · cm−2 and poured into the pool through a network of bottom inlet pipes. Twice a week, the walls and bottom of the pool are mechanically cleaned by divers. The animals are not cleaned, and since their relocation to the Africarium have not suffered from any major illnesses or disorders. Thus, no additional treatments were applied. The enclosure is lit by artificial light from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m.. Apart from the manatees, the pool is inhabited by several freshwater fish species: predators such as Clarotes laticeps, Heterobranchus longifilis, Hydrocynus goliath, Hydrocynus vittatus, a herbivorous species Distichodus atroventralis, and a non-specialized species Heterotilapia buttikoferi. Individuals of the latter graze eagerly on the shedding manatee skin, whereas the rest of the fish are functionally neutral and do not directly affect the sirenians. On the day of sampling, the manatees were not overgrown with algae, neither any unusual skin coloration nor discoloration was noticed.

Skin biofilm was taken with single-use sterile toothbrushes using sampling procedures applied previously in the sea turtle diatom studies (Pinou et al. 2019). Material collection was performed by qualified zoo staff members. The applied techniques were fully non-invasive and did not cause any detectable signs of stress or discomfort in the animals. Each sample was split into two parts: one for the fresh material observation and culturing and one for detailed ultrastructural analyses with both LM and SEM. In addition, concentration of the total dissolved silicon (Si) and iron (Fe) in the manatee enclosure were measured with a SPECTRO ARCOS inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES; SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany).

Diatom biofilm was cleaned through rapid digestion with a 2:1 mixture of boiling concentrated nitric (63%) and sulphuric (98%) acids following the protocol described by von Stosch (Hasle and Syvertsen 1997). Subsequently, the digested material was rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, pipetted onto the glass coverslips, air-dried, and mounted on slides with Pleurax. The permanent slides, as well as fresh material (manatee skin flakes with living diatoms attached), were examined using a Nikon 80i light microscope with Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and a Nikon DS-Fi1 5MP digital camera.

Fifty cells (i.e., 10 per every medium prepared) were isolated using a glass pipette into 16 × 100 mm glass culture tubes filled with f/2 growth medium (Guillard 1975) prepared based on distilled water (freshwater medium), filtered seawater (34), and seawater dilutions (4, 8, and 17). In addition, “raw” cultures were prepared by pipetting a few drops of the fresh material into the glass culture flasks filled with the five versions of growth medium. The culture tubes and flasks were maintained at 24–28°C and lit by natural light from a south-facing window.

For SEM observations, the cleaned diatom material was filtered through 1.2-μm Isopore™ polycarbonate membrane filters (Merck Millipore), mounted on aluminium stubs with carbon tape and sputter-coated with iridium using an Emitech K575X (Emitech Ltd., Ashford, Kent, UK) sputter-coater. Specimens were analyzed with JEOL JSM-7001F (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) scanning electron microscopes at 5 kV. The morphology of the epizoic diatoms found was compared with images and information available in the relevant literature (e.g., Holmes et al. 1989, 1993, Wetzel et al. 2012, Frankovich et al. 2015a,b, 2018, Riaux-Gobin et al. 2017).

Results and Discussion

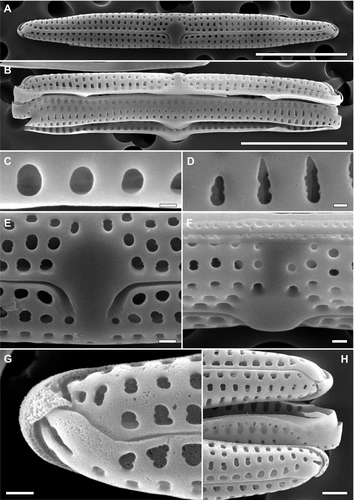

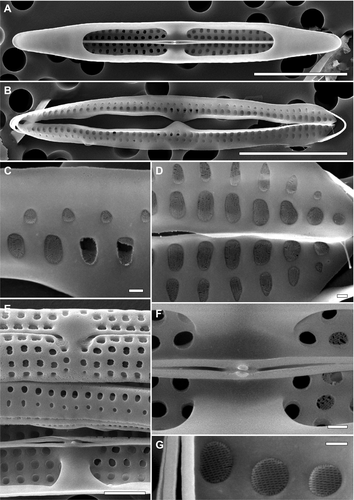

Total dissolved Si concentration in the water from the manatee enclosure was 5.46 mg · L−1, i.e., higher than Si levels typical for seawater, but comparable to those reported from rivers (Cox 1989, Yabutani et al. 1999). Total dissolved Fe was 0.7 μg · L−1, being within the ranges recorded from various marine habitats (Yabutani et al. 1999, Boyd and Ellwood 2010). The analyses showed that all biofilm samples were dominated by one diatom species, Tursiocola cf. ziemanii, that each time contributed > 99.9% to the total diatom number (Figs. 1, B–F; 2, A–H; 3, A–G). Sporadically, frustules of Planothidium sp. were also found (Fig. 1B, arrow). Observations of the fresh material revealed that all Tursiocola specimens were apochlorotic, whereas the rare Planothidium cells were normally pigmented (Fig. 1, B and C). Tursiocola cf. ziemanii from the Wroclaw manatees were 13–51 μm long and 2–3.5 μm wide (n > 500), which overlaps with the morphometrics given for Tursiocola ziemanii in the species description (20–61 μm and 2.4–5.2 μm, respectively; Frankovich et al. 2015b). However, the recorded stria density ranged from 27 to 32 in 10 μm, whereas in specimens observed by Frankovich et al. (2015b) these values were lower, ranging from 22 to 25 in 10 μm. Moreover, specimens collected from the captive manatees presented somewhat larger and more roundish areolae (both on the valve face and girdle bands l Figs. 2, A–H; 3, A–G) than frustules illustrated in the species description (Frankovich et al. 2015b). Although, to some degree, this difference might have been enhanced by different coating material applied (iridium vs. gold/palladium) and its thickness (Abdullah et al. 2014), as additional 10 nm of coating material may reduce the areola diameter of up to 20 nm (R. Majewska, pers. obs.). Despite multiple culturing attempts and a wide range of salinity of the medium used, T. cf. ziemanii did not grow. Interestingly, Planothidium sp. isolated from the manatee skin showed remarkable euryhalinity, surviving and growing in each of the prepared media (“raw” cultures; salinity of 0–34).

Although molecular analyses could not be performed at this time, we believe that the dominant taxon may be conspecific with Tursiocola ziemanii described from the Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus laterorostris), a subspecies of the West Indian manatee (Frankovich et al. 2015b, 2018). Polymorphy, as well as significant morphological plasticity in diatoms, including phenotypic responses to external factors, are not uncommon, and changes in both stria density and areolae shape may be induced by differences in environmental conditions (Cox 2014, Edlund and Burge 2019, and references therein). In the case of the Africarium manatees and their wild relatives, differences in environmental parameters such as salinity (or salinity fluctuations), nutrient concentration, water dynamics, or light regime would be substantial. As previous reports describe features of T. ziemanii associated with a population of manatees encountered within a certain geographic region (Florida Bay and Crystal River, FL, USA; Frankovich et al. 2015b, 2018), they may not necessarily reflect the full range of intraspecific plasticity in this taxon.

The high-quality SEM images allowed us to document pore arrangement of the hymenes occluding the girdle areolae (Figs. 2, C and D; 3, C and D). This feature has not yet been described from any of Tursiocola species. The arrangement of hymen pores covering the valve areolae agreed with the description given by Holmes et al. (1993), who reported that hymenes in the cetacean species T. olympica showed “a linear array of elongate pores” (Figs. 2, E and G; 3, E–G). Currently, this character is one of the two features (the second being the lack or presence of stauros or the “butterfly structure”) discriminating Tursiocola from another epizoic genus, Epiphalaina, whose areolae possess “hymenes arranged more or less concentrically”. However, our observations show that the more or less concentric arrangement of pores is present also in the girdle areolae hymenes of Tursiocola (Figs. 2, C and D; 3, C and D). The images further revealed that all areolae in Tursiocola are occluded internally (Figs. 2, C–H; 3, C–G).

This study provides compelling evidence that the relationship between the epizoic Tursiocola cf. ziemanii and their host is an intimate and most likely an obligatory one. As all of the manatees sampled were captive-born, including both the adults and the juvenile born in the Africarium, these diatoms must have survived for decades growing on at least two generations of captive animals in the artificial conditions that differed substantially from their natural environment. Recently, six presumably exclusively epizoic Tursiocola species were described from the skin of multiple individuals of the Florida manatee (Frankovich et al. 2015b, 2018). Four of the diatom taxa, including T. ziemanii, were reported to be apochlorotic (Frankovich et al. 2018). Although other diatoms were present, Tursiocola spp. accounted for nearly 90% of the total diatom number (Frankovich et al. 2015b). Among these, T. ziemanii was the most abundant taxon comprising from 55% to 83% of the diatoms counted (Frankovich et al. 2018). We speculate that T. zeimanii, being a dominant epizoic diatom species closely related to the host manatee captured in the natural environment, survived under drastically changed condition because its development is limited by the availability of the animal substratum rather than any of the abiotic environmental factors. It is likely that new, captive–born generations of manatees were inoculated with epizoic diatoms through physical contact with the adult individuals present in the enclosure.

The skin of the Africarium manatees appeared much cleaner than in the wild Florida manatees observed in the Florida Bay (FL, USA; R. Majewska, pers. obs.), despite the lack of any additional treatments applied by the Africarium. Pigmented diatoms (Planothidium sp.) contributed less than 0.01% to the total diatom number, whereas other photosynthetic organisms, such as macroalgae or cyanobacteria, were not detected during the fresh material observations with LM. This might be caused by both the abiotic factors, such as unfavorable light conditions or the freshwater medium, and the biotic ones (i.e., the presence of fish grazing on the shedding manatee skin). While light is most likely of no or secondary importance to apochlorotic Tursiocola cf. ziemanii, growth of other microalgae may be strongly compromised by insufficient irradiation. In those unfavorable conditions, even the opportunistic diatom species do not survive in competition with highly adapted Tursiocola. As noticed by Woodworth et al. (2019), the recently described manatee–associated macroalga, Melanothamnus maniticola, died back during the prolonged residence of manatees at a freshwater site. Permanent freshwater conditions may be challenging to many unspecialized taxa that would attach to the manatee biofilm in a particular stage of the animal migrations between the marine and freshwater environments, but would occupy the animal habitat only temporarily, as long as the external factors support their development. Moreover, presence of the grazer, Heterotilapia buttikoferi, would prevent the excessive development of any surface–associated organisms, especially those loosely attached to the skin, further promoting the dominance of small, truly epizoic taxa dwelling directly on the animal tissue and being the only diatoms able to recolonize the bare skin exposed by constant nibbling by fish.

It was proposed that long-distance migrations to warm waters in whales allow them the “routine skin maintenance”, as, in low-latitude environments, the epidermal moult may need to be deferred. Cold polar waters, although abundant in prey, would reduce blood flow to the animal skin and thus preclude the normal skin shedding (Pitman et al. 2019). Undoubtedly, enhanced skin moulting would help reduce fouling by various epibionts. At the same time, dramatic change in environmental conditions may further limit the number of fouling organisms not adapted to such large fluctuations in temperature or salinity. Thus, it cannot be excluded that migrations to freshwater habitats in manatees may be necessary to maintain healthy skin.

The animal microbiome often plays an essential role in animal well-being, and better understanding of the animal-microbial associations may bring enormous improvements to the methods and procedures used to maintain the health of captive animals. Measures should be taken to support not only the appropriate development of the captive animal but also its microbiome. As, most likely, the former cannot be achieved without the latter. We believe that the presence and dominance of the epizoic Tursiocola on the Africarium manatees contributes to the good condition of their skin and thus overall well-being. The original, species–specific microbiome may reduce the chance of pathogens’ development and transmission and prevent skin dehydration, simply by occupying the available space and competing with other microbes. Although further studies are required to shed more light on the specific role of epizoic diatoms (including the biochemistry of diatom metabolites and their influence on the living substratum and other members of the animal microbiome), it becomes clear that these organisms are not merely opportunistic hitchhikers.

Conclusions

The apochlorotic and presumably exclusively epizoic Tursiocola cf. ziemanii dominates the diatom communities on captive–born manatees even when the external conditions provided by the zoo (e.g., salinity, light regime) differ substantially from those encountered in the natural environment. At the same time, the manatee substratum seems to be the main limiting factor for the development of this taxon.

Tursiocola possesses areolae with hymenes showing both linear (valve face) and concentrical (girdle bands) array of pores. All areolae in Tursiocola are occluded internally.

Practices and routines used by the zoo affect the epidermal microbiome of captive animals, and measures should be taken to maintain the native microbiome and enhance its development as it may directly or indirectly influence the host animal health and well-being.

The authors thank Jakub Kordas, Agnieszka Urbanczyk, Emiliana Morka, Maciej Ryba (Africarium, Wroclaw Zoo, Wroclaw, Poland), and Filip F. Pniewski (Gdansk University, Gdynia, Poland) for their invaluable help during the material and data collection, great enthusiasm, and unceasing support to the project. The Wroclaw Zoo authorities are thanked for their permission to conduct the study. Jan Neethling and the staff from the Centre for High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy, Nelson Mandela University (Port Elizabeth, South Africa) are acknowledged for their generous help during the SEM analyses. Furthermore, the authors thank Matt P. Ashworth (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, USA), Thomas A. Frankovich (Florida International University, Key Largo, USA), and one anonymous reviewer for valuable comments on the previous version of this manuscript.