Taxing the Financially Integrated Multinational Firm

I would like to thank Peter Birch Sørensen and Marko Koethenbuerger for valuable comments and suggestions. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Danish Council for Independent Research.

Abstract

This paper develops a theoretical model of corporate taxation in the presence of financially integrated multinational firms. Under the assumption that multinational firms use some measure of internal loans to finance foreign investment, we find that the optimal corporate tax rate is positive from the perspective of a small, open economy. This finding contrasts the standard result that the optimal-source-based capital tax is zero. Intuitively, when multinational firms finance investment in one country with loans from affiliates in another country, the burden of the corporate taxes levied in the latter country partly falls on investment and thus workers in the former country. This tax exporting mechanism introduces a scope for corporate taxes, which is not present in standard models of international taxation. Accounting for the internal capital markets of multinational firms thus helps resolve the tension between standard theory predicting zero capital taxes and the casual observation that countries tend to employ corporate taxes at fairly high rates.

1. Introduction

At the heart of the multinational firm is the internal capital market that allocates funds inside the firm. Affiliates of multinational firms typically finance investment with a combination of funds from external sources such as bank loans and bond emissions and funds from internal sources such as equity injections and loans from related entities. The internal capital market thus creates financial linkages within the multinational firm in the sense that affiliates are tied together by internal loans and equity stakes. The multinational firm is financially integrated.

The MiDi data set collected by the German Central Bank and recently made available for research provides a unique opportunity to assess the nature and size of these financial linkages within the multinational firm. A remarkable feature highlighted by this data set is the prevalence of internal loans. Buettner and Wamser (2013) report that foreign affiliates of German firms have an average total debt-asset ratio of around 0.60, which breaks down into an external debt-asset ratio of 0.35 and an internal debt-asset ratio of 0.25. This suggests that internal loans represent a source of financing that is quantitatively almost as important as external loans. The internal debt-asset ratio further breaks down into a parent debt-asset ratio of 0.15 and an other affiliate debt-asset ratio of 0.10. This suggests that parents as well as other affiliates are important lenders in the internal capital markets of multinational firms.1

The main contribution of this paper is to show that financial linkages within multinational firms have important implications for optimal taxation of capital. The paper develops a model of corporate taxation in the presence of financially integrated multinational firms while assuming that foreign investment of multinational firms is financed with some measure of internal loans and that these internal loans are not exclusively motivated by profit shifting. These assumptions find strong support in the empirical facts about German firms documented in the MiDi data set. Not only do foreign affiliates of German firms receive around one quarter of their capital in the form of loans from related entities, but most of these loans derive from affiliates in high-tax countries: Buettner and Wamser (2013) report that around half of the internal loans derive from the parent in Germany where the corporate tax rate has consistently been very high by international standards, while Ruf and Weichenrieder (2012) report that the other half mostly derive from affiliates in high-tax countries (e.g., the United States and the United Kingdom) and only to a much smaller extent from affiliates in low-tax havens (e.g., Cayman Islands, Ireland, Switzerland, and Luxembourg). To the extent that internal lending was predominantly driven by profit shifting, we should observe internal loans flowing from low-tax countries to high-tax countries; however, we actually observe most internal loans flowing out of high-tax countries. This pattern is not inconsistent with the large body of literature finding that the financial structure of multinational firms is tax-sensitive, but it certainly seems to imply that other considerations than profit shifting play an important role in determining flows of capital within the multinational firm.

The main finding of the paper is that internal loans serving other purposes than profit shifting introduce a tax exporting mechanism that causes the optimal corporate tax rate to be positive from the perspective of a small, open economy. This contrasts with the standard result that the optimal tax on investment is zero (Gordon 1986). Intuitively, small, open economies are facing a perfectly elastic supply of capital; hence, any tax that raises the cost of investment is fully shifted to the workers. In the standard model with only domestic firms, this implies that corporate taxes are strictly dominated by labor taxes because they distort the labor supply to the same extent as labor taxes and add a distortion of the capital–labor ratio. In our model, multinational firms partly finance investment with loans from foreign affiliates. This is effectively shifting the tax base from the country of the investing affiliate to the countries of the lending affiliates because interest payments are deductible in the former country and taxable in the latter. To the extent that corporate taxes fall on interest income from loans to foreign affiliates, they raise the cost of investing in foreign countries and are therefore borne by foreign workers. This provides a tax exporting motive for using corporate taxes, which is absent in the standard model.

Returning to the internal capital markets of German firms discussed above, the paper essentially argues that the interest income generated by loans from German parents to foreign affiliates represents a tax base to which Germany should optimally apply a positive tax rate. Intuitively, taxing income that derives from loans to foreign entities has no impact on the cost of investing in the taxing country itself but generates revenue by adding to the cost of investing in foreign countries. The first-best tax system thus combines a zero tax rate on income from domestic investment as in the standard model with a positive tax on income deriving from loans to foreign affiliates. In a standard corporate tax system where a uniform tax rate applies to all corporate income, however, the optimal corporate tax rate is strictly positive and balances the benefits of taxing corporations in terms of tax exporting and the costs of taxing them in terms of a distorted capital–labor ratio.

The paper relates to several strands of literature. First, a few existing papers describe other tax exporting mechanisms. Gordon (1992) shows that when countries apply the credit principle to the taxation of foreign source income, capital taxes in the source country have no bearing on the total tax burden on investment but erode the tax revenue of the home country. Huizinga and Nielsen (1997) show that source taxes on the normal return to capital are partly shifted to foreign owners of domestic firms through a reduction in economic rents. The present paper adds to this literature by exposing a novel tax exporting mechanism whereby capital taxes are partly shifted to foreign workers through a reduction in foreign wages.

Second, a series of papers analyzes capital taxation in the presence of financially integrated multinational firms while focusing exclusively on financial strategies that allow multinational firms to shift the corporate tax base between jurisdictions. Huizinga, Laeven, and Nicodeme (2008) present a model of debt shifting where a disproportionate share of the external debt of multinationals is allocated to affiliates in high-tax countries in order to increase the tax value of the debt. A number of papers including Mintz and Smart (2004), Fuest and Hemmelgarn (2005), and Johannesen (2012) develop models of profit shifting where tax haven affiliates finance other affiliates with internal loans. Generally, the use of tax-motivated financial strategies like debt shifting and profit shifting tends to increase the tax sensitivity of capital tax bases and reinforce the race-to-the-bottom in capital tax rates. The present paper shows that the use of nontax-motivated financial strategies can also contribute to just the opposite result.

Third, a few recent papers study the interaction between internal loans and corporate tax policy in the form of thin capitalization rules, which are tax provisions limiting the deductibility of interest payments on internal loans with the aim of curbing profit shifting. Buettner et al. (2012) show empirically that thin capitalization rules significantly reduce the extent to which multinational firms rely on internal lending. Haufler and Runkel (2012) demonstrate theoretically how lax thin capitalization rules can serve as a tax competition device targeted at internationally mobile capital and how a coordinated tightening of thin capitalization rules can yield positive welfare effects.

Finally, a number of papers address the fundamental question why countries raise considerable revenue with source-based capital taxes. Gordon and Varian (1989) show that country-specific productivity shocks resurrect the case for positive capital taxes because the desire of foreign investors to hedge risk implies that the demand for domestic capital is imperfectly elastic with respect to the net-of-tax return; Gordon and MacKie-Mason (1994) argue that income shifting between different tax bases introduces a scope for using a capital income tax since the latter works as a back-stop for the personal income tax; Haufler and Wooton (1999) find that trade costs can give rise to location-specific rents that countries optimally appropriate by means of source-based capital taxes; Wildasin (2003) shows that under imperfect capital mobility, optimal capital taxes are positive and inversely related to the speed with which the capital stock adjusts in response to changes in the local return to capital; Fuest and Huber (2002) find that the optimal source tax is positive if other countries apply the credit or deduction principle to the taxation of foreign source income due to the tax exporting mechanism discussed by Gordon (1992). The present paper contributes to this literature by exploring a novel explanation for the fact that most countries levy corporate taxes at fairly high rates. Our theory is similar to Fuest and Huber (2002) in assigning a key role to the multinational firm, but the mechanism driving the result is clearly distinct in the two models.2

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2. develops the model framework. Section 3. derives the baseline results on optimal capital taxation in the presence of financially integrated multinational firms. Section 4. extends the results to a model where firms' financial structure is endogenous and responsive to taxation. Section 5. extends the results to a setting where financially integrated multinational firms coexist with purely domestic firms. Section 6. provides some concluding remarks.

2. The Baseline Model

We consider a world economy with a large number of small countries. Each country is inhabited by a single representative agent endowed with  units of capital and

units of capital and  units of labor. We adopt the standard assumptions that capital is perfectly mobile across countries, whereas labor is immobile. Because of the countries' smallness, policy decisions in individual countries have a negligible impact on the required return to capital r that is determined on international capital markets. The preferences of the representative agent are represented by the utility function

units of labor. We adopt the standard assumptions that capital is perfectly mobile across countries, whereas labor is immobile. Because of the countries' smallness, policy decisions in individual countries have a negligible impact on the required return to capital r that is determined on international capital markets. The preferences of the representative agent are represented by the utility function  where C is private consumption, X is leisure, and G is public expenditure. The utility function is assumed to be separable in consumption and leisure on the one hand and public expenditure on the other hand,

where C is private consumption, X is leisure, and G is public expenditure. The utility function is assumed to be separable in consumption and leisure on the one hand and public expenditure on the other hand,  , which implies that the choice between consumption and leisure is independent of the level of public expenditure.3 We let L denote labor supply and thus establish the following identity:

, which implies that the choice between consumption and leisure is independent of the level of public expenditure.3 We let L denote labor supply and thus establish the following identity:  . Firms produce according to the standard production function

. Firms produce according to the standard production function  with constant returns to scale where K denotes the capital. There is free entry of firms and firms therefore earn zero profits in equilibrium.

with constant returns to scale where K denotes the capital. There is free entry of firms and firms therefore earn zero profits in equilibrium.

Governments are benevolent and have access to two tax instruments: a labor tax  and a capital tax

and a capital tax  . For expositional simplicity, we assume that taxes fall directly on production factors and not on the income they generate.4 The tax base of the labor tax is thus L. The tax base of the capital tax is the stock of capital invested in the country K reduced by financial liabilities (the analog of deductible interest expenses) and augmented by financial assets (the analog of taxable interest income). Since firms earn no pure profits, the capital tax is equivalent to a standard corporate tax on profits net of labor costs and interest expenses. We adopt the standard assumption that governments are unable to enforce taxes on the capital income of households, for instance, due to imperfect information about foreign assets. We also assume that profits of foreign subsidiaries are tax-exempt (the territoriality principle).

. For expositional simplicity, we assume that taxes fall directly on production factors and not on the income they generate.4 The tax base of the labor tax is thus L. The tax base of the capital tax is the stock of capital invested in the country K reduced by financial liabilities (the analog of deductible interest expenses) and augmented by financial assets (the analog of taxable interest income). Since firms earn no pure profits, the capital tax is equivalent to a standard corporate tax on profits net of labor costs and interest expenses. We adopt the standard assumption that governments are unable to enforce taxes on the capital income of households, for instance, due to imperfect information about foreign assets. We also assume that profits of foreign subsidiaries are tax-exempt (the territoriality principle).

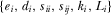

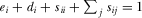

The main departure from the standard model of international taxation is the assumption that producing entities are affiliates of multinational firms, which implies that they receive capital from a number of different sources. Specifically, for a producing entity in country i we define  as the fraction of its capital that is injected by affiliates in the form of equity;

as the fraction of its capital that is injected by affiliates in the form of equity;  as the fraction that is borrowed in external capital markets;

as the fraction that is borrowed in external capital markets;  as the fraction that is borrowed from affiliates in the same country; and

as the fraction that is borrowed from affiliates in the same country; and  as the fraction that is borrowed from foreign affiliates in country j. We allow firms to be heterogenous along several dimensions: they may differ by the number of countries in which they operate as well as by the allocation of productive capacity between these countries. Our framework thus allows firms to be “home-biased” in the sense that the scale of production is larger at the parent entity than at foreign affiliates and economic integration to be “regional” in the sense that firms in a given country only have foreign affiliates in one or few partner countries. The only symmetry that we need to impose is that all producing entities in a given country have the same financial structure: the same share of equity, the same share of external debt, and the same distribution of internal debt across foreign counterpart countries.5

as the fraction that is borrowed from foreign affiliates in country j. We allow firms to be heterogenous along several dimensions: they may differ by the number of countries in which they operate as well as by the allocation of productive capacity between these countries. Our framework thus allows firms to be “home-biased” in the sense that the scale of production is larger at the parent entity than at foreign affiliates and economic integration to be “regional” in the sense that firms in a given country only have foreign affiliates in one or few partner countries. The only symmetry that we need to impose is that all producing entities in a given country have the same financial structure: the same share of equity, the same share of external debt, and the same distribution of internal debt across foreign counterpart countries.5

Arguably, our most important assumption is that internal cross-border lending, while possibly sensitive to taxation, is not entirely driven by profit shifting so that intrafirm loans may to some extent flow from a country i to a country j where the tax rate is lower. In Section 1., we argued that this assumption is consistent with the basic patterns in the data on multinational firms' capital structure. In the following, we will briefly review the various explanations offered by the literature for the fact that the financial structure of multinational firms is typically not tax minimizing. First, Desai et al. (2004) show empirically that multinational firms extend more internal loans to foreign subsidiaries in countries with weak creditor rights where the cost of external loans tends to be higher. This suggests that the choice between internal and external financing is influenced not only by tax factors but also by the quality of external capital markets. Second, drawing on the principal-agency framework of Jensen (1986), several authors suggest that if local managers are concerned with the size of the specific subsidiary that they operate whereas the objectives of the central management relate to the performance of the global firm, debt financing represents an instrument to prevent excessive growth in subsidiaries with a large cash flow (e.g., Huizinga et al. 2008). Such considerations clearly influence the choice between internal and external sources of financing but could also have a bearing on the choice between internal debt and equity to the extent that interest payments specified ex ante represent a harder claim on subsidiary profits than dividend payments decided ex post on the basis of available accounting profits. Third, Chowdry and Coval (1998) show theoretically that with uncertainty about future earnings a high-tax parent company optimally finances a low-tax foreign subsidiary with some measure of internal loans since in some states of the world the interest income at the level of the parent company is shielded by losses. Fourth, Dischinger, Knoll, and Riedel (2014) discuss the possibility that the well-known notion of rent sharing between firm owners and workers may induce the central management to finance operating subsidiaries with internal debt rather than equity in order to erode accounting profits and mitigate wage pressure. Finally, it should be noted that internal loans constitute a much more flexible way to transfer funds within the firm than equity from a corporate law perspective, which may also explain why firms in some cases rely on loans for internal financing even when associated with a tax cost relative to equity.6

Another important assumption is that governments cannot impose taxation on household savings income. The difficulties related to enforcement of capital taxes on households in the country where they reside are well known and the assumption that capital income is untaxed at the household level is standard in the tax competition literature.7 The main issue is offshore tax evasion: if households hold savings through foreign custodian banks, it is very hard for tax authorities to detect and tax the corresponding capital income.8 Yet, one may wonder whether our main result would still hold if we were to assume that taxes on household savings were enforceable? In the present framework where savings are exogenous, this would give governments a nondistortionary tax instrument; hence, the use of the corporate tax would only be optimal if its tax exporting effects were strong enough to outweigh its distortionary effects. However, a fully satisfactory answer to the question would necessitate a more elaborate modeling of the household savings decision, which is outside the scope of this paper.9

3. Optimal Taxation in the Baseline Model

In this section, we assume that all firms are financially integrated multinational firms with a fixed financial structure. This facilitates the exposition of the role of financial linkages in shaping tax policy by allowing us to treat the financial structure  as a set of constant parameters and to abstract from purely domestic firms. As noted in Section 1., there is strong empirical evidence that the financial structure of multinational firms is tax-sensitive. In the next section, we therefore analyze an extended model where firms optimally choose the financial structure given the tax environment. Moreover, a significant share of the revenue from corporate taxation derives from domestic firms with no financial ties to foreign entities. In the following section, we therefore develop a two-sector model where financially integrated multinational firms coexist with domestic firms.

as a set of constant parameters and to abstract from purely domestic firms. As noted in Section 1., there is strong empirical evidence that the financial structure of multinational firms is tax-sensitive. In the next section, we therefore analyze an extended model where firms optimally choose the financial structure given the tax environment. Moreover, a significant share of the revenue from corporate taxation derives from domestic firms with no financial ties to foreign entities. In the following section, we therefore develop a two-sector model where financially integrated multinational firms coexist with domestic firms.

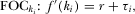

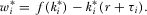

3.1. Capital and Labor Market Equilibrium

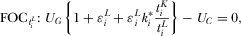

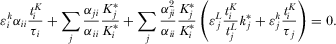

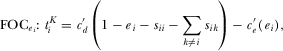

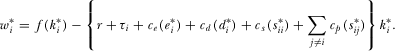

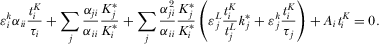

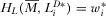

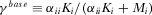

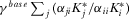

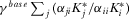

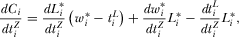

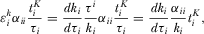

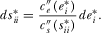

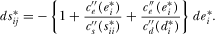

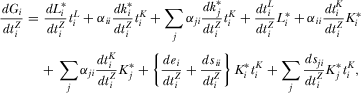

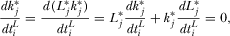

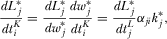

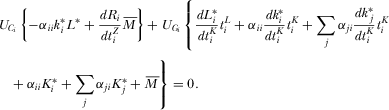

denotes the effective tax rate on capital in country i, which is given by

denotes the effective tax rate on capital in country i, which is given by

(1)

(1) gives the global tax burden associated with investment in country i given the parameters of the financial structure. The first term reflects taxes on equity at the level of the producing entity. The last terms represent taxes on debt claims at the level of the lending affiliates. It is useful to note already at this stage that

gives the global tax burden associated with investment in country i given the parameters of the financial structure. The first term reflects taxes on equity at the level of the producing entity. The last terms represent taxes on debt claims at the level of the lending affiliates. It is useful to note already at this stage that  depends on capital tax rates in country i as well as all the countries from which internal loans flow into country i. Specifically, a fraction

depends on capital tax rates in country i as well as all the countries from which internal loans flow into country i. Specifically, a fraction  of the capital invested in country i is taxed in country i, whereas a fraction

of the capital invested in country i is taxed in country i, whereas a fraction  of the capital invested in country i is taxed in country

of the capital invested in country i is taxed in country  . The fact that operating entities in country i are partly financed with loans from affiliates in country j thus implies that countries i and j effectively share the capital tax base generated by capital investment in country i. This is at the heart of the tax exporting mechanism. A fraction

. The fact that operating entities in country i are partly financed with loans from affiliates in country j thus implies that countries i and j effectively share the capital tax base generated by capital investment in country i. This is at the heart of the tax exporting mechanism. A fraction  of the capital stock is effectively untaxed. This corresponds to the usual tax advantage of external debt financing when interest expenses are deductible from the corporate tax base and the corresponding interest income is not effectively taxed at the investor level.

of the capital stock is effectively untaxed. This corresponds to the usual tax advantage of external debt financing when interest expenses are deductible from the corporate tax base and the corresponding interest income is not effectively taxed at the investor level. and the function

and the function  . Using these definitions and the assumption of constant returns to scale in the production technology, we restate the profit maximization problem of the firm in the following way:

. Using these definitions and the assumption of constant returns to scale in the production technology, we restate the profit maximization problem of the firm in the following way:

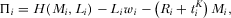

and

and  read

read

(2)

(2) (3)

(3) as a decreasing function of the cost of capital

as a decreasing function of the cost of capital  and may thus be interpreted as a capital demand function. Equation (3) defines the equilibrium wage rate

and may thus be interpreted as a capital demand function. Equation (3) defines the equilibrium wage rate  for a given optimal capital-labor ratio and cost of capital:

for a given optimal capital-labor ratio and cost of capital:

(4)

(4) would induce firms to contract (expand) the scale of their operations infinitely; hence,

would induce firms to contract (expand) the scale of their operations infinitely; hence,  is the unique wage rate compatible with equilibrium. Equation (4) may thus be interpreted as (the inverse of) the labor demand function.

is the unique wage rate compatible with equilibrium. Equation (4) may thus be interpreted as (the inverse of) the labor demand function. , the tax rate on labor

, the tax rate on labor  , and nonlabor income

, and nonlabor income  .

.

(5)

(5) (6)

(6) . We impose throughout the paper that the labor supply is positively related to the net-of-tax wage

. We impose throughout the paper that the labor supply is positively related to the net-of-tax wage  . The equilibrium capital stock

. The equilibrium capital stock  follows directly from

follows directly from  and

and  .

.Summing up, Equations 2, 4, 5, and 6 define the equilibrium economic outcomes ( ) in country i conditional on the tax policy variables and the world return to capital r. Note that

) in country i conditional on the tax policy variables and the world return to capital r. Note that  is decreasing in the return to capital (in fact, both

is decreasing in the return to capital (in fact, both  and

and  are decreasing in

are decreasing in  —the latter through the equilibrium wage

—the latter through the equilibrium wage  ).

).

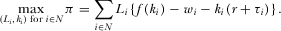

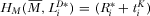

3.2. Tax Policy

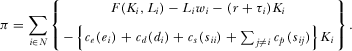

while correctly anticipating how capital and labor market outcomes respond to taxes. Public expenditure is given by the following expression:

while correctly anticipating how capital and labor market outcomes respond to taxes. Public expenditure is given by the following expression:

(7)

(7) represents a link between government revenue in country i and investment in other countries since the tax base in country i includes loans granted by entities in country i to affiliates in other countries.

represents a link between government revenue in country i and investment in other countries since the tax base in country i includes loans granted by entities in country i to affiliates in other countries. corresponding to the assumptions of the standard model where firms are completely equity-financed. In this special case, we have

corresponding to the assumptions of the standard model where firms are completely equity-financed. In this special case, we have  and

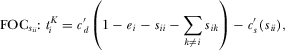

and  ; hence, there are no intrafirm financial linkages and the scope for tax exporting is effectively eliminated. Inserting 5 and 7 into the utility function, we can derive the following first-order conditions for utility maximization with respect to the labor tax rate

; hence, there are no intrafirm financial linkages and the scope for tax exporting is effectively eliminated. Inserting 5 and 7 into the utility function, we can derive the following first-order conditions for utility maximization with respect to the labor tax rate  and the capital tax rate

and the capital tax rate  , respectively (see Appendix):

, respectively (see Appendix):

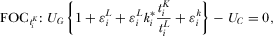

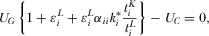

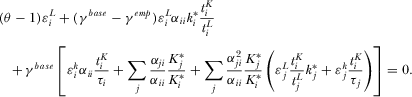

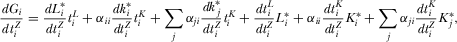

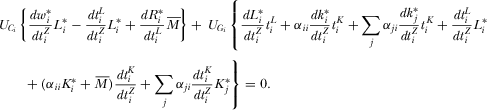

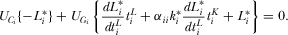

(8)

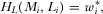

(8) (9)

(9) is the elasticity of the labor supply

is the elasticity of the labor supply  with respect to the labor tax rate

with respect to the labor tax rate  and

and  is the elasticity of the capital–labor ratio

is the elasticity of the capital–labor ratio  with respect to the effective capital tax rate

with respect to the effective capital tax rate  , which in this special case equals

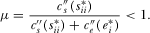

, which in this special case equals  . It is easy to see that 8 and 9 require that

. It is easy to see that 8 and 9 require that  , which only holds when

, which only holds when  . We summarize this result in the following proposition:

. We summarize this result in the following proposition:

PROPOSITION 1.When operating subsidiaries are fully equity-financed  , the optimal tax rate on capital is zero.

, the optimal tax rate on capital is zero.

This proposition restates the result derived by Gordon (1986) as a special case where firms are fully equity-financed.10 It is instructive to inspect the first-order conditions in more detail. The expressions in curly brackets in (8 ) and 9 capture the inverse marginal cost of public funds for each of the two tax instruments, which is the amount of public revenue raised with the labor tax and the capital tax, respectively, for each unit of private consumption foregone. For  , the marginal deadweight loss has two terms, both related to labor supply responses and thus proportional to the tax elasticity of the labor supply. The first term

, the marginal deadweight loss has two terms, both related to labor supply responses and thus proportional to the tax elasticity of the labor supply. The first term  represents changes in the labor tax revenue, whereas the second term

represents changes in the labor tax revenue, whereas the second term  represents changes in the capital tax revenue. The latter effect owes itself to the fact that changes in the labor supply

represents changes in the capital tax revenue. The latter effect owes itself to the fact that changes in the labor supply  produce proportional changes in the capital tax base

produce proportional changes in the capital tax base  for a given capital–labor ratio

for a given capital–labor ratio  . For

. For  , the marginal deadweight loss has the same two terms and an additional term

, the marginal deadweight loss has the same two terms and an additional term  . The first two terms reflect that capital taxes reduce the net-of-tax wage

. The first two terms reflect that capital taxes reduce the net-of-tax wage  by exactly the same amount as labor taxes per dollar of revenue raised where capital taxes work through changes in the gross wage rate

by exactly the same amount as labor taxes per dollar of revenue raised where capital taxes work through changes in the gross wage rate  . The third term captures the distortion of the capital-labor ratio introduced by the capital tax. It follows directly that labor taxes raise more revenue than capital taxes per unit of private consumption foregone and that capital taxes should therefore not be employed. In brief, capital taxes distort the labor supply to the same extent as labor taxes, and moreover distort the capital–labor ratio of firms; hence, they are inferior to labor taxes.

. The third term captures the distortion of the capital-labor ratio introduced by the capital tax. It follows directly that labor taxes raise more revenue than capital taxes per unit of private consumption foregone and that capital taxes should therefore not be employed. In brief, capital taxes distort the labor supply to the same extent as labor taxes, and moreover distort the capital–labor ratio of firms; hence, they are inferior to labor taxes.

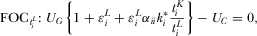

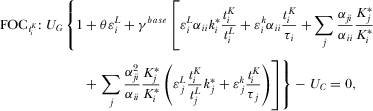

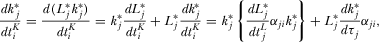

and the capital tax rate

and the capital tax rate  are (see Appendix)

are (see Appendix)

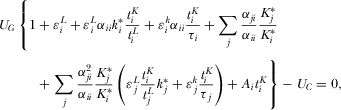

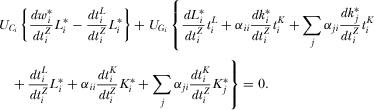

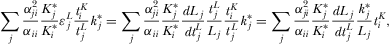

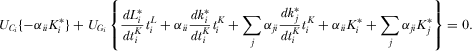

(10)

(10) (11)

(11)As before, the expressions in curly brackets express the inverse marginal cost of public funds. For  , the marginal cost of public funds is identical to the case of fully equity-financed firms except for the factor

, the marginal cost of public funds is identical to the case of fully equity-financed firms except for the factor  on the last term, which reflects that behavioral responses reducing the capital stock

on the last term, which reflects that behavioral responses reducing the capital stock  now have a smaller revenue effect since only a fraction

now have a smaller revenue effect since only a fraction  of it is effectively taxed in country i. For

of it is effectively taxed in country i. For  , the marginal cost of public funds includes the same terms as for

, the marginal cost of public funds includes the same terms as for  and four additional terms. We consider these terms in turn. The first term

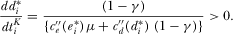

and four additional terms. We consider these terms in turn. The first term  is the equivalent of the last term inside the curly brackets in equation 9 and captures the marginal deadweight loss associated with distortions of the capital–labor ratio

is the equivalent of the last term inside the curly brackets in equation 9 and captures the marginal deadweight loss associated with distortions of the capital–labor ratio  . The second term

. The second term  is the tax exporting effect, which reflects that capital taxes in country i are partly borne by workers in country j. Intuitively, the tax exporting effect is increasing in the foreign capital stock effectively subject to domestic capital taxation

is the tax exporting effect, which reflects that capital taxes in country i are partly borne by workers in country j. Intuitively, the tax exporting effect is increasing in the foreign capital stock effectively subject to domestic capital taxation  and decreasing in the domestic capital stock effectively subject to domestic capital taxation

and decreasing in the domestic capital stock effectively subject to domestic capital taxation  . The final two terms capture behavioral responses in country j that erode capital tax revenues in country i. Intuitively, capital taxes in country i raise effective capital taxation in country j and thus lower the capital stock, which is partly subject to taxation in country i, through reductions in both

. The final two terms capture behavioral responses in country j that erode capital tax revenues in country i. Intuitively, capital taxes in country i raise effective capital taxation in country j and thus lower the capital stock, which is partly subject to taxation in country i, through reductions in both  and

and  .

.

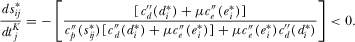

(12)

(12) is positive, whereas all other terms are proportional to and have the opposite sign as

is positive, whereas all other terms are proportional to and have the opposite sign as  (see Appendix). It follows that only a tax vector

(see Appendix). It follows that only a tax vector  with

with  can satisfy Equations 10 and 11. We summarize this result in the following proposition:

can satisfy Equations 10 and 11. We summarize this result in the following proposition:

PROPOSITION 2.When operating subsidiaries have a fixed financial structure with some cross-border internal loans  , the optimal capital tax rate is strictly positive.

, the optimal capital tax rate is strictly positive.

The result reported in Proposition 2 is driven by tax exporting. Capital taxes in country i raise the cost of capital in both countries i and j and part of the tax burden is therefore borne by workers in country j through a reduction in  . Capital taxes still have the undesirable effect of distorting the capital–labor ratio; however, the marginal deadweight loss is second-order when evaluated at the undistorted starting point

. Capital taxes still have the undesirable effect of distorting the capital–labor ratio; however, the marginal deadweight loss is second-order when evaluated at the undistorted starting point  . It follows that the optimal capital tax rate is positive.

. It follows that the optimal capital tax rate is positive.

It should be noted that Proposition 2 does not characterize the equilibrium capital tax rate but conveys the stronger finding that country i optimally chooses a positive capital tax rate regardless of the tax policies chosen by country j.

4. Endogenous Financial Structure

The purpose of this section is to show that the main result presented in Proposition 2 holds when the financial structure of the multinational firm responds to changes in the tax environment. We do not explicitly model the multitude of determinants of the optimal financial structure, but adopt a reduced-form specification. It is assumed that there exists a target financial structure, which is optimal absent tax considerations, and that tax-motivated deviations from the target financial structure are associated with real costs. The most important implication of this specification is that the different sources of financing are imperfect substitutes. The optimal financial structure is thus shaped by tax incentives but is not tax-minimizing as would be the case if the different sources of financing were perfect substitutes. These properties are consistent with the empirical facts about the financial structure of multinational firms reviewed above. They are also consistent with the literature on the internal capital markets stressing the role of external capital markets, agency costs, rent sharing, and uncertainty about future earnings in shaping the financial structure of multinational firms.

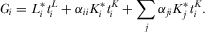

4.1. Capital and Labor Market Equilibrium

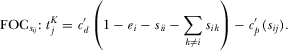

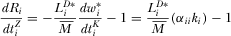

where

where  is the target level; (ii)

is the target level; (ii)  ; and (iii)

; and (iii)  . The same properties are assumed for

. The same properties are assumed for  , and

, and  . The assumptions about the cost functions imply that the marginal cost of moving a financial structure variable away from its target level is strictly increasing in the initial distance to the target level. We do not attach any particular interpretation to the cost functions but consider them a convenient modeling device that allows us to analyze the empirically relevant case of imperfectly substitutable sources of financing in a simple and flexible way. It should also be noted that the cost functions do not capture deep policy-invariant trade-offs within the firm. While they may be taken to be exogenous to the tax policies analyzed in the paper, they are likely to be endogenous to many other policies such as regulation of bankruptcies, creditor rights, and so on.

. The assumptions about the cost functions imply that the marginal cost of moving a financial structure variable away from its target level is strictly increasing in the initial distance to the target level. We do not attach any particular interpretation to the cost functions but consider them a convenient modeling device that allows us to analyze the empirically relevant case of imperfectly substitutable sources of financing in a simple and flexible way. It should also be noted that the cost functions do not capture deep policy-invariant trade-offs within the firm. While they may be taken to be exogenous to the tax policies analyzed in the paper, they are likely to be endogenous to many other policies such as regulation of bankruptcies, creditor rights, and so on.

. Using the identity

. Using the identity  , the first-order conditions for

, the first-order conditions for  , and

, and  can be stated as

can be stated as

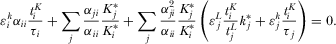

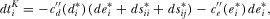

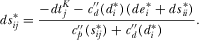

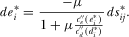

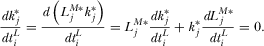

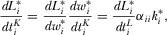

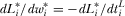

(13)

(13) (14)

(14) (15)

(15) for

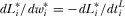

for  . It is easy to see that in the absence of capital taxes, only the target financial structure satisfies the first-order conditions. It can be shown that a small increase in

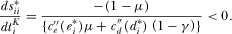

. It is easy to see that in the absence of capital taxes, only the target financial structure satisfies the first-order conditions. It can be shown that a small increase in  causes the following changes to the optimal financial structure of the subsidiary in country i: (i) an increase in external loans

causes the following changes to the optimal financial structure of the subsidiary in country i: (i) an increase in external loans  ; (ii) an increase in internal loans from other countries

; (ii) an increase in internal loans from other countries  , (iii) a decrease in internal loans from the same country

, (iii) a decrease in internal loans from the same country  ; and (iv) a decrease in equity

; and (iv) a decrease in equity  (see Appendix). Intuitively, the firm responds to increased taxation in country i by adjusting the financial structure so as to reduce the share of the capital stock that is taxed in the country itself (

(see Appendix). Intuitively, the firm responds to increased taxation in country i by adjusting the financial structure so as to reduce the share of the capital stock that is taxed in the country itself ( ) and raise the shares of the capital stock that is taxed in other countries and untaxed (

) and raise the shares of the capital stock that is taxed in other countries and untaxed ( ). By the same logic, a small increase in

). By the same logic, a small increase in  causes a decrease in

causes a decrease in  offset by increases in

offset by increases in  ,

,  and

and  .

. can be stated as

can be stated as

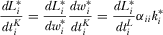

(16)

(16) conditional on the capital structure.

conditional on the capital structure. can be stated as

can be stated as

(17)

(17)

. The equilibrium capital stock

. The equilibrium capital stock  follows directly from

follows directly from  and

and  .

.4.2. Tax Policy

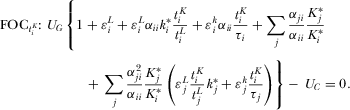

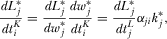

and

and  , respectively (see Appendix):

, respectively (see Appendix):

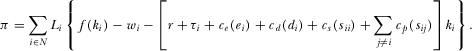

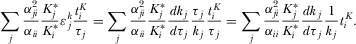

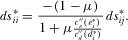

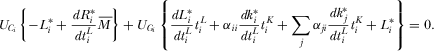

(18)

(18) (19)

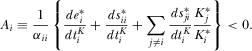

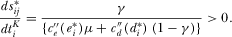

(19)

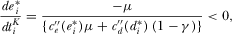

, which represents the revenue effect of the adjustments to the optimal financial structure induced by a marginal increase in

, which represents the revenue effect of the adjustments to the optimal financial structure induced by a marginal increase in  . We note that

. We note that  is unambiguously negative, which derives from the fact that multinational firms respond to tax increases in country i by adjusting all dimensions of their financial structure in order to reduce the tax base in country i.

is unambiguously negative, which derives from the fact that multinational firms respond to tax increases in country i by adjusting all dimensions of their financial structure in order to reduce the tax base in country i. :

:

are proportional to and have the opposite sign as

are proportional to and have the opposite sign as  , which implies that only a tax vector

, which implies that only a tax vector  with

with  can satisfy Equations 18 and 19. We summarize this analysis in the following proposition:

can satisfy Equations 18 and 19. We summarize this analysis in the following proposition:

PROPOSITION 3.When operating subsidiaries have an optimally chosen financial structure and the different sources of financing are imperfect substitutes, the optimal capital tax rate is strictly positive.

Intuitively, capital taxes in country i trigger adjustments of the financial structure that erode the capital tax base in country i; however, evaluated at  , the marginal deadweight loss is of second order. The revenue gain associated with exporting of capital taxes is of first order; hence, the optimal capital tax rate is strictly positive.

, the marginal deadweight loss is of second order. The revenue gain associated with exporting of capital taxes is of first order; hence, the optimal capital tax rate is strictly positive.

5. Two-Sector Economy

The baseline model assumes that all firms are financially integrated multinationals, whereas in the real world many firms are only present in a single country and have no financial links to foreign entities. To investigate whether our results are robust to the presence of domestic firms, this section extends the analysis to a setting where two sectors coexist in the economy: multinational firms producing with labor and mobile capital and domestic firms producing with labor and immobile capital (for instance, land or entrepreneurial human capital embedded in the immobile workers). In addition to their endowments of labor ( ) and mobile capital (

) and mobile capital ( ), workers are endowed with

), workers are endowed with  units of immobile capital that they supply inelastically to firms in the domestic sector. Workers can move costlessly between sectors, which implies that a single wage applies to the entire economy.11

units of immobile capital that they supply inelastically to firms in the domestic sector. Workers can move costlessly between sectors, which implies that a single wage applies to the entire economy.11

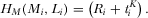

5.1. Capital and Labor Market Equilibrium

As in the baseline model, the optimal capital intensity of multinational firms  is determined uniquely by 2. Moreover, due to free entry in the multinational sector, the equilibrium wage rate

is determined uniquely by 2. Moreover, due to free entry in the multinational sector, the equilibrium wage rate  equals the wage rate that yields zero profits in multinational firms and is given by 4.

equals the wage rate that yields zero profits in multinational firms and is given by 4.

is a standard production function with constant returns to scale and

is a standard production function with constant returns to scale and  is the return to immobile capital. Domestic firms hire labor and immobile capital until

is the return to immobile capital. Domestic firms hire labor and immobile capital until

(20)

(20) (21)

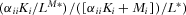

(21)Clearing of the market for immobile capital requires that demand equals the fixed supply  . Hence, the equation

. Hence, the equation  implicitly determines the equilibrium amount of labor employed in the domestic sector

implicitly determines the equilibrium amount of labor employed in the domestic sector  , whereas the equation

, whereas the equation  determines the equilibrium return to immobile capital

determines the equilibrium return to immobile capital  . Profits in domestic firms are zero by Euler's theorem. The total amount of labor employed in the economy

. Profits in domestic firms are zero by Euler's theorem. The total amount of labor employed in the economy  is determined by (4), whereas the equilibrium amount of labor employed in the multinational sector

is determined by (4), whereas the equilibrium amount of labor employed in the multinational sector  is given by

is given by

.

.

5.2. Tax Policy

(22)

(22) (23)

(23) from their endowments of immobile capital and the government raises revenue

from their endowments of immobile capital and the government raises revenue  from taxing immobile capital. Inserting 22 and (23) into the utility function, we can derive the first-order condition for utility maximization with respect to the labor tax rate

from taxing immobile capital. Inserting 22 and (23) into the utility function, we can derive the first-order condition for utility maximization with respect to the labor tax rate  (see Appendix):

(see Appendix):

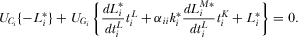

(24)

(24) is the share of total employment in the multinational sector. Equation 24 differs from the analogous equation in the baseline model (10) only by the factor

is the share of total employment in the multinational sector. Equation 24 differs from the analogous equation in the baseline model (10) only by the factor  in the last term inside the curly brackets, which implies that the labor tax ceteris paribus is associated with a smaller deadweight loss than in the one-sector model. Intuitively, the labor tax generates revenue in both sectors at the expense of a lower labor supply, but it is only in the multinational sector that a lower labor supply leads to a lower level of taxable capital.

in the last term inside the curly brackets, which implies that the labor tax ceteris paribus is associated with a smaller deadweight loss than in the one-sector model. Intuitively, the labor tax generates revenue in both sectors at the expense of a lower labor supply, but it is only in the multinational sector that a lower labor supply leads to a lower level of taxable capital. (see Appendix):

(see Appendix):

(25)

(25)

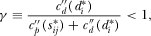

is the intensity of domestically taxable capital in the multinational sector relative to the economy as a whole and

is the intensity of domestically taxable capital in the multinational sector relative to the economy as a whole and  is the share of the total capital tax base in the multinational sector. Equation 25 differs from the analogous equation in the baseline model 11 in two respects. First, all the terms related to changes in the capital tax base (collected in square brackets) are multiplied by the factor

is the share of the total capital tax base in the multinational sector. Equation 25 differs from the analogous equation in the baseline model 11 in two respects. First, all the terms related to changes in the capital tax base (collected in square brackets) are multiplied by the factor  , which implies that the capital tax ceteris paribus is associated with a smaller deadweight loss than in the baseline model. While a small increase in the capital tax mechanically raises the revenue collected in both sectors, it is only in the multinational sector that it distorts the capital intensity; hence, the deadweight loss is decreasing in the employment share of the multinational sector. Second, the labor supply elasticity is multiplied by the factor θ. Intuitively, the cost of raising the capital tax rate in terms of a lower wage rate (leading to reduced labor supply and loss of labor tax revenue) is proportional to the intensity of (domestically taxable) capital in the multinational sector, whereas the benefit in terms of increased revenue is proportional to the intensity of (domestically taxable) capital in the economy as a whole. In the one-sector model, these two factors are the same and cancel out, but this is not necessarily the case in the present two-sector model.

, which implies that the capital tax ceteris paribus is associated with a smaller deadweight loss than in the baseline model. While a small increase in the capital tax mechanically raises the revenue collected in both sectors, it is only in the multinational sector that it distorts the capital intensity; hence, the deadweight loss is decreasing in the employment share of the multinational sector. Second, the labor supply elasticity is multiplied by the factor θ. Intuitively, the cost of raising the capital tax rate in terms of a lower wage rate (leading to reduced labor supply and loss of labor tax revenue) is proportional to the intensity of (domestically taxable) capital in the multinational sector, whereas the benefit in terms of increased revenue is proportional to the intensity of (domestically taxable) capital in the economy as a whole. In the one-sector model, these two factors are the same and cancel out, but this is not necessarily the case in the present two-sector model. (26)

(26)To proceed with the analysis, we distinguish between three cases. First, when  , the optimality condition simply requires that the expression inside the square brackets equals zero, which is identical to the optimality condition in the one-sector model 12.12 In this case, the labor tax and the capital tax distort the labor supply to precisely the same extent, so the optimal size of the capital tax again depends on the trade-off between the positive tax-exporting effect through intrafirm loans and the negative effect through distortion of the capital intensity in the multinational sector. While both of these effects are smaller in magnitude than in the one-sector model because they now only occur in one of the economy's two sectors, they are scaled down by the same factor

, the optimality condition simply requires that the expression inside the square brackets equals zero, which is identical to the optimality condition in the one-sector model 12.12 In this case, the labor tax and the capital tax distort the labor supply to precisely the same extent, so the optimal size of the capital tax again depends on the trade-off between the positive tax-exporting effect through intrafirm loans and the negative effect through distortion of the capital intensity in the multinational sector. While both of these effects are smaller in magnitude than in the one-sector model because they now only occur in one of the economy's two sectors, they are scaled down by the same factor  , which means that the trade-off between them is unchanged. Hence, the optimal policy vector remains the same as in the one-sector model. This result, which mirrors Propositions 1 and 2, is summarized in Proposition 4.

, which means that the trade-off between them is unchanged. Hence, the optimal policy vector remains the same as in the one-sector model. This result, which mirrors Propositions 1 and 2, is summarized in Proposition 4.

PROPOSITION 4.When the two sectors are equally intensive in domestically taxable capital ( ):

):

- (A) The optimal capital tax rate is zero (

) when multinational firms are fully equity-financed (

) when multinational firms are fully equity-financed ( ).

). - (B) The optimal capital tax rate is positive (

) when multinational firms are partly financed with intrafirm loans (

) when multinational firms are partly financed with intrafirm loans ( ).

).

Second, when  , all terms in 26 are proportional to and have the opposite sign as

, all terms in 26 are proportional to and have the opposite sign as  except

except  , which is positive, and

, which is positive, and  , which is negative. In the absence of intrafirm loans (

, which is negative. In the absence of intrafirm loans ( ), the latter term dominates the former, in which case no positive value of

), the latter term dominates the former, in which case no positive value of  can satisfy the optimality condition. In the presence of intrafirm loans (

can satisfy the optimality condition. In the presence of intrafirm loans ( ), the former term dominates the latter whenever θ is not too large, and in this case, only a positive value of

), the former term dominates the latter whenever θ is not too large, and in this case, only a positive value of  can satisfy the optimality condition. Intuitively, when

can satisfy the optimality condition. Intuitively, when  , the capital tax distorts the labor supply more than the labor tax relative to the revenue it raises, which implies that it can only be optimal to use it at a positive rate if the tax exporting effect through intrafirm loans is sufficiently large. These findings are summarized in Proposition 5.

, the capital tax distorts the labor supply more than the labor tax relative to the revenue it raises, which implies that it can only be optimal to use it at a positive rate if the tax exporting effect through intrafirm loans is sufficiently large. These findings are summarized in Proposition 5.

PROPOSITION 5.When the multinational sector is more intensive in domestically taxable capital than the domestic sector ( ):

):

- (A) the optimal capital tax rate is nonpositive (

) when multinational firms are fully equity-financed (

) when multinational firms are fully equity-financed ( );

); - (B) the optimal capital tax rate is positive (

) when multinational firms are partly financed with intrafirm loans (

) when multinational firms are partly financed with intrafirm loans ( ) provided that θ is not too large.

) provided that θ is not too large.

Third, when  , all terms in 26 are proportional to and have the opposite sign as

, all terms in 26 are proportional to and have the opposite sign as  except

except  and

and  , the sum of which is strictly positive. It follows that only a positive value of

, the sum of which is strictly positive. It follows that only a positive value of  can satisfy the optimality condition. Intuitively, when

can satisfy the optimality condition. Intuitively, when  , the capital tax distorts the labor supply less than the labor tax relative to the revenue it raises, which implies that it is optimal to use it at a positive rate even without tax exporting through intrafirm loans. This result is summarized in Proposition 6.

, the capital tax distorts the labor supply less than the labor tax relative to the revenue it raises, which implies that it is optimal to use it at a positive rate even without tax exporting through intrafirm loans. This result is summarized in Proposition 6.

PROPOSITION 6.When the multinational sector is less intensive in domestically taxable capital than the domestic sector ( ), the optimal capital tax rate is positive (

), the optimal capital tax rate is positive ( ) regardless of the financial structure of multinational firms.

) regardless of the financial structure of multinational firms.

In summary, this section has shown that, although differences in capital intensity across sectors affect the relative attractiveness of labor and capital taxes when the economy comprises both multinational and domestic firms, the basic tax-exporting mechanism identified in the main analysis still exists. In particular, there is a range of values of the key parameter θ where the optimal capital tax is zero when multinational firms are fully equity-financed and positive when they are partly financed with intrafirm debt.

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper has developed a model of corporate taxation in the presence of financially integrated multinational firms. The two key assumptions of the model—and the main departure from standard models of international taxation—relate to the internal capital markets of multinational firms. Specifically, it was assumed that multinational firms partly finance foreign investment with internal loans and that internal loans are not entirely driven by a profit-shifting motive. The main finding is that the presence of internal loans introduces a tax-exporting motive for corporate taxes. Intuitively, to the extent that multinational firms finance investment in one country with loans from affiliates in another country, the burden of corporate taxes in the latter country partly falls on investment and thus workers in the former country. Our model thus helps resolve the tension between the standard result that the optimal-source-based capital tax is zero and the casual observation that most countries employ corporate taxes at nonnegligible rates.

), a nonnegative fraction of internal debt from domestic lenders (

), a nonnegative fraction of internal debt from domestic lenders ( ), and zero internal debt from foreign lenders (

), and zero internal debt from foreign lenders ( ).

). is sufficiently large such that the domestic sector always hires some labor and that

is sufficiently large such that the domestic sector always hires some labor and that  is sufficiently small such that the domestic sector never hires all the labor in the economy.

is sufficiently small such that the domestic sector never hires all the labor in the economy. when

when  .

.Appendix A

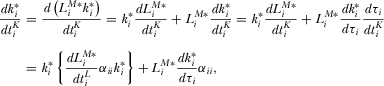

1 Section 3.2.: Derivation of 8–11

Country i maximizes individual utility with respect to its two tax policy instruments  . The tax policies shape the economic equilibrium in the country itself

. The tax policies shape the economic equilibrium in the country itself  and in the countries to which it is connected by multinational firms

and in the countries to which it is connected by multinational firms  through equations 2, 4, and (6), whereas the return to capital r is given exogenously from the world capital market. This economic equilibrium, in turn, determines the outcomes of interest to the individual: private consumption

through equations 2, 4, and (6), whereas the return to capital r is given exogenously from the world capital market. This economic equilibrium, in turn, determines the outcomes of interest to the individual: private consumption  and government expenditure

and government expenditure  given by 5 and 7, respectively.

given by 5 and 7, respectively.

reads

reads

(27)

(27) . Using expressions 5 and 7 and the definition of

. Using expressions 5 and 7 and the definition of  , we derive the following expressions:

, we derive the following expressions:

(28)

(28) (29)

(29) (30)

(30) (31)

(31) (32)

(32) (33)

(33) (34)

(34)2 Section 3.2.: Proof of Proposition 2

Since  and

and  by 2 and

by 2 and  by assumption, it follows that all three (set of) terms are negative when

by assumption, it follows that all three (set of) terms are negative when  , zero when

, zero when  and positive when

and positive when  . When the financial structure involves some cross-border internal lending (

. When the financial structure involves some cross-border internal lending ( ), the second set of terms

), the second set of terms  is strictly positive; hence, only when

is strictly positive; hence, only when  can 12 hold.

can 12 hold.

3 Section 4.1: Derivation of Responses of Financial Structure to Tax Change

(37)

(37) (38)

(38) (39)

(39) (40)

(40) (41)

(41) (42)

(42) (43)

(43) (44)

(44) . Insert 44 into 40 and then 43 into the resulting expression. Set

. Insert 44 into 40 and then 43 into the resulting expression. Set  and rearrange to obtain

and rearrange to obtain

(45)

(45)

(46)

(46) (47)

(47) that

that

(48)

(48) . Set

. Set  , insert 43 into 40 and rearrange to obtain

, insert 43 into 40 and rearrange to obtain

4 Section 4.2.: Derivation of 18 and 19

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain 19.

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain 19.5 Section 5.: Derivation of 24 and 25

The derivation of the first-order conditions for optimal tax policy follows Section 3.2. closely. To save space, we only restate equations that differ from their counterparts in that section.

remains 27, whereas the effect of tax rates on private consumption and public expenditure become

remains 27, whereas the effect of tax rates on private consumption and public expenditure become

(49)

(49) (50)

(50) (51)

(51) using 32 yields

using 32 yields

(52)

(52) : the endogenous domestic-sector variables

: the endogenous domestic-sector variables  and

and  are uniquely determined by

are uniquely determined by  and

and  that are both unaffected by the labor tax rate. Moreover, we derive the following relations between the labor tax rate and the mobile capital stock:

that are both unaffected by the labor tax rate. Moreover, we derive the following relations between the labor tax rate and the mobile capital stock:

Biography

Niels Johannesen, Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen, Denmark ([email protected]).

using

using

follows from

follows from

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain  where

where  to obtain

to obtain  using

using

that follows from

that follows from

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain  where

where  and

and  to obtain

to obtain

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain  while using

while using

which follows from

which follows from

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain

and rewrite in terms of elasticities to obtain