Developing a Transition Tool for Young Adults With Neurodevelopmental Conditions

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Transition from paediatric to adult healthcare is a challenging time for young adults with neurodevelopmental conditions (NDC). The fragmentation and deficits in health, social and disability systems, and the increasing numbers of people with NDC, mean a more guided transition focusing on health independence is needed. This study aimed to develop a holistic transition tool and identify areas for improvement in transition services based on the consensus of experts involved with the care of children with NDC in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Methods

Utilising the Delphi method, two rounds (Round One: open-ended, Round Two: Likert scale) of online questionnaires involving 61 panellists (healthcare professionals, educators and caregivers) reviewed areas for improvement in transition services and ideas for a transition tool.

Results

In Round One, Delphi participants identified seven themes related to transition services, including processes, resources, professionals, governance and culture; and 10 themes related to components of the tool, including communication, healthcare management, rights, activities, supports and community connectedness, whānau/family, culture, mental and spiritual health and sexual health. In Round Two, 94% of the ideas for transition services items reached consensus (26% with strong consensus [> 95%]). All the components of the transition tool reached consensus, and 62% of items reached strong consensus (> 95%).

Conclusion

This study provides direction on key domains related to transition services and a framework for a transition tool for young adults with NDC in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Its inclusion of domains related to culture, mental and spiritual health, rights for young adults, family involvement and community connectedness is a first step in developing a holistic approach to support a successful transition.

Summary

-

What is known about this topic

- ○

The transition period from paediatric to adult services is challenging for young adults with neurodevelopmental conditions.

- ○

A poor transition experience can lead to poor long-term health and wellbeing outcomes.

- ○

There is consensus that improvements are needed in the transition of youth with neurodevelopmental conditions into the adult health system.

- ○

-

What this paper adds

- ○

Identifies critical gaps in current transition services and ideas for supporting transition in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

- ○

Identifies domains that should be included in a transition tool for young adults with neurodevelopmental conditions.

- ○

Highlights the importance of culture in ensuring a holistic transition programme and provides a springboard for future research to pilot the transition tool in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

- ○

1 Introduction

The Society for Adolescent Medicine defines the transition to adult medical care as ‘the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centred to adult-orientated health care systems’ [1]. Due to advances in healthcare practices, it is estimated that up to 90% of children with chronic healthcare needs survive into adulthood [2]. Transition to adulthood is an important stage of emotional, psychosocial and psychological development, and it is a period when considerations about independent living and vocational opportunities arise [3].

The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines neurodevelopmental conditions (NDCs) as ‘a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period…that produce impairments of personal, social, academic, or occupational functioning’ [4]. Neurodisability describes a group of congenital or acquired long-term conditions that are attributed to impairment of the brain and/or neuromuscular system and create functional limitations [5]. In this manuscript, we use the DSM-5 definition when referring to NDCs. Young adults with NDCs encounter challenges during transition, due to individual intrinsic complexities, differing cognitive abilities, multiple comorbidities, multisystem involvement and deficits within health and disability care systems. This leads to variation in transition planning, ad-hoc implementation, increased anxiety associated the transition process and greater parental reluctance to leave paediatric care compared with young adults with chronic illness [6]. For those with severe NDCs, the transition to adult healthcare coincides with other transfers, such as the shift from school to day placements, and/or from home to supported living or other new residential arrangements, as well as legal and financial changes [6]. The combined psychosocial and environmental factors leads to long-term negative outcomes which increases the risk for behavioural adjustment, mental health problems and lower self-esteem [6].

There is consensus that the transition of young adults with NDCs into the adult health system requires improvement. Gleeson and colleagues put it starkly, ‘this lack of focus on young people as a group with particular health care needs in medical training and health service underpins the difficulty that we have experienced as a profession in improving transition’ [7]. Several transition programmes have shown good feasibility, acceptability, satisfaction and self-efficacy, however more robust published evaluations are needed to show effectiveness [8]. Strategies currently utilised to aid transition include transition clinics, role of a transition coordinator, facilitating paperwork and implementation of clinical guidelines and education [9].

Among developed transition tools for chronic conditions are the Ready Steady Go transition tool [10] and the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) [11]. Although adaptable, these tools were not sufficient to meet the increased needs required by young adults with NDCs. The Surrey Transition Checklist was created to help caregivers and youth with NDCs effectively discuss the necessary skills to transition to adult life. However, similar to other established interventions, cultural aspects are often neglected in the with only 8% of studies considering the cultural paradigms in the development and implementation phase [9]. Any tool developed for the Aotearoa, New Zealand context must take into account Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the inequitably higher burden of NDCs experienced by Māori and Pacific children [12].

This study aimed to achieve expert consensus around key components to be included in a holistic transition tool for young adults with NDDs in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and to identify current gaps in transition services and supports from the perspective of parents, carers and service providers.

2 Methods

2.1 Aims

- Obtain local consensus on domains and items for a transition tool for young adults with NDCs in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

- Obtain perspectives from families, carers, and those who provide services to children with NDCs on current gaps in transition services and supports required.

2.2 Study Design

We utilised the Delphi method, which is a structured iterative process engaging an anonymous panel of experts with diverse areas of expertise in a series of rounds involving questionnaires. These rounds are repeated until consensus is reached. It provides a method to engage group opinion, which is assumed to have greater validity and reliability than individual opinion [13, 14]. Initially, we conceptualised this project primarily as a tool to assist healthcare transition in young adults with NDCs. However, a secondary goal was to ensure the study was robust enough to ensure holistic approaches to health, which means a secondary outcome includes domains that may sit outside the classic biomedical model of health. The first round involved a series of open-ended questions, with subsequent rounds based on Likert scale responses. The study was conducted between 1 July 2021, and 1 February 2023. For this study, panellists were emailed two rounds of online questions using 2022 Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) [15].

Potential panellists were identified by the research team using purposive, convenience and snowball sampling and were selected using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Participants involved with and/or experienced in the care of young adults with NDCs were eligible to participate, including clinicians, allied healthcare professionals, specialist school educators, parents/caregivers, consumer advocates, and adults with lived experience of NDCs.

- Adults who were caregivers for children with NDCs < 18 years of age.

- Provide written informed consent.

- Unwilling or unable to provide written informed consent.

- Children/young adults < 18 years of age with lived experience of NDCs.

Panel members were approached either in person or via electronic mail and sent a personalised invitation letter and accompanying participant information sheet. After agreement to participate was obtained, panellists completed and returned a consent form.

Round One: Upon seeking permission from the Surrey Place Transition Team, open-ended questions were developed using the study aims and the Surrey Place Transition Checklist [8]. The panel was also sent eight questions pertaining to demographics, including: gender, age, ethnicity, role in care for young adults with NDCs, years of experience in the profession, work setting, experience with NDCs and years involved with the care of children with NDCs or disabilities in general.

Round Two: Second round questions were developed based on the thematically analysed responses from open-ended questions in Round One. Two broad categories emerged: (1) ideas for a transition tool based on seven themes and 38 subtheme statements, and (2) ideas for transition services based on 10 themes and 87 subthemes. Panel members were asked to rate each statement using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Unimportant, 2 = Unimportant, 3 = Neither Unimportant or Important 4 = Important, 5 = Very Important) with respect to services for NDCs transition and inclusion in a transition tool. Panel members were able to respond to Round Two independent of their participation in Round One.

Additional Delphi rounds were performed until consensus was reached. For any question, a threshold of 70% agreement among participants was taken to indicate that consensus had been reached, and no further Delphi rounds were required.

2.3 Analysis

Round One open-ended questions were analysed by the first author using content and thematic analysis. Themes were reviewed by the rest of the authorship team. A second iteration of thematic analysis involved grouping themes under two broad categories of ‘ideas for supporting transition’ and ‘what to include in a tool’. Demographics, response rates and Round Two results were analysed using descriptive statistics in R Core Team 2023 [16]. Distributions were described using medians and interquartile ranges for Delphi panel scores on a 5-point Likert scale for each domain as described above. Consensus was deemed to be reached when at least 70% of respondents selected ‘Important’ or ‘Very Important’ for a theme or item, and a median rating of ≥ 4 and interquartile range of ≤ 1 was achieved [17]. Subtopics with a consensus level > 95% were considered to have reached a strong consensus.

3 Results

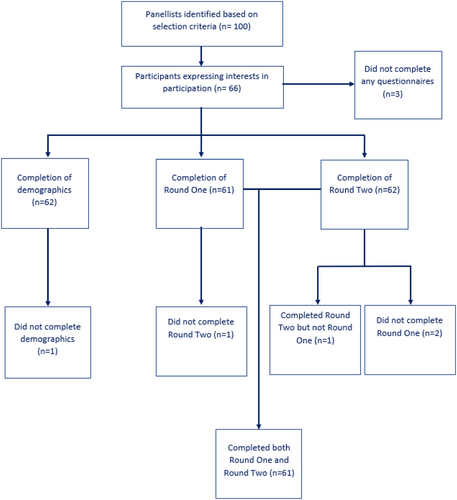

An initial list of 100 potential panellists was identified by the research team with 66 in the final panel; the response rate was 95% (Figure A1). The majority of panellists were female (76%) and most of the panellists were aged between 25 and 54 years. One fifth of the participants were Māori/Pacific Peoples. Over 80% of the panellists worked in healthcare, with two thirds working in a community setting (Table A1).

Content and thematic analysis of Round One and Round Two generated 10 finalised themes and 87 subthemes with regards to ideas for a transition tool, and seven themes and 38 subthemes with regards to ideas for supporting transition. Round One open-ended responses are presented in Table A2 with selected quotes from panellists that demonstrate insights into each theme and their subtopics.

Round two Likert scale rankings of subtopic statements within each theme are presented in Table A3 and Table A4. Of the items for inclusion in a transition checklist, 100% of the items reached consensus (87/87), with 39% (34/87) of items reaching strong consensus. Of the ideas for transition services, 92% of items (35/38) reached consensus, with 26% of items (10/38) reaching strong consensus. Overall consensus had been reached on > 90% of the statements in Round Two. A further round was not deemed necessary as per the study protocol.

4 Discussion

4.1 Principal Findings

In this study, expert panellists with experience of supporting young people with NDC reached consensus on 10 themes with subitems for inclusion in a new transition tool and reached consensus on seven themes with subitems for ideas for improving transition services. There was strong consensus for more than one quarter of the items relating to ideas for improving transition services and for more than one third of the items for inclusion in the transition tool. In particular, novel items not seen in previous tools, which reached strong consensus, were in the domains of: culture, mental and spiritual health, role of whanau/family and supports and community connectedness.

Once young people move into adult health settings, there is a loss of access to a primary specialist such as a paediatrician, with greater reliance on general practitioners (GPs) to assume holistic care. It was surprising that statements on GPs being better equipped in terms of funding, training, exposure, supportiveness and service flexibility did not reach a consensus among the group. While there may be arguments that too much pressure is being placed on overstretched primary care services, currently, GPs play an integral role in providing care for the transitioning young adult, and it could be argued that GPs should be better equipped to provide such services. Our results suggest that the expert panel valued more resource for the development of transition supports which reduce the burden on GPs, such as nurse-led transition clinics. Creating a nationwide transition service was another statement that did not reach consensus. This may be due to perceived challenges in coordinating transition at local and regional levels, and across diverse conditions, with panellists questioning the feasibility of a nationwide service.

4.2 Principal Findings in Relation to Other Studies

To our knowledge, this is the first study from Aotearoa, New Zealand exploring improved transition approaches for young adults with NDCs. A Delphi method was chosen due to the strength of enabling a diverse panel to provide feedback and reach consensus anonymously. Constraints around the Delphi method include the lack of universal guidelines which determine the threshold for consensus. In this study, consensus thresholds were based on previously published Delphi studies [17, 18]. A unique aspect of the study was the inclusion of a broad conceptualisation of what transition entails, including holistic wellbeing constructs of including culture and indigenous conception of wellbeing.

Among existing literature, the inclusion of culture as a consideration in transition is rare. A scoping review found that only 8% of papers described the relevance of cultural paradigms for the transition of young people with NDCs, with most relating to the linguistic translation of tools [9]. For the Aotearoa, New Zealand context, the involvement of whānau/family, beliefs and indigenous culture are important to ensure that obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi are upheld, and to support equitable and responsive transition experiences. This ties in with indigenous Māori principles of Mana (promoting persons pride and identity) and Manaakitanga (collective wellbeing of connected communities). To ensure the inclusion of Māori conceptions of health, the questionnaire included items relating to the four dimensions of health and wellbeing within Te ao Māori (indigenous Māori worldview): taha tinana (physical wellbeing), taha hinengaro (mental wellbeing), taha wairua (spiritual wellbeing) and taha whānau (family wellbeing) [19]. In line with this, as pointed out by one of the panellists, there is also a nee d for consultation with Iwi (tribes) to ensure transition practices follow correct Tikanga (procedure, practice or protocol) and to provide a culturally appropriate and applicable transition tool.

Previous studies on approaches for improved transition for young adults with NDCs have focused on developing checklists [20], training and/or education initiatives [21], transition meetings, clinics and/or establishing guidelines of best practice [22, 23]. Our Delphi panel reached consensus on all of these approaches being important for the delivery of effective transition support, with the addition of governance, child/youth agency and rights and cultural supports.

From a social perspective, the transition process may be a daunting experience for many young adults with NDC, as they have previously been heavily reliant on parents/caregivers for support. However, gradually introducing vocational training, community-based programmes and support groups enables young adults to develop the necessary social skills to navigate life independently. Social skills development is essential; for example, education in sexual safety strategies and community safety [24]. The utility of respite care was strongly recommended by our panellists in supporting the mental wellbeing of family/whānau. From a cost perspective, respite care has also been shown to reduce crisis management requirements for young adults with NDCs [24].

Patient navigators and family-centred service providers play an important role in improving access to respite care. Patient navigators enable information sharing, create a collaborative network and reduce the burden upon individual families to find care for children and young people [25]. Improving patient navigation aligns with the Enabling Good Lives framework, an approach developed by members of the New Zealand disability community, which shifts power from government services toward empowering disabled people and their families to make decisions appropriate for themselves [26].

4.3 Study Strengths

This study provides the foundation for the development of a new transition tool, which has the ability to provide practical support to improve transition experiences for young people and their whānau/families. The transition process should ideally incorporate shared decision-making involving the young adult, their family/whānau and members of the multidisciplinary team, including specialist and primary health practitioners, educators and school staff and community health service providers. A new transition tool can be utilised as a focal point for multidisciplinary discussions that identify existing gaps in a young person's existing supports and plans for an optimal transition experience that is tailored to the young person's and family's/whānau aspirations. Our study was culturally inclusive and highlights the importance of Te Ao Māori perspectives in ensuring a culturally appropriate transition tool. Future research that develops and pilots a new transition tool, based upon our study findings, is an important next step.

4.4 Study Limitations

Only two people with lived experience and a few caregivers were included among the panellists. The majority of the panellists were European and healthcare professionals with a limited number of consumer advocates. This study did not include children/young adults < 18 years of age with NDCs. Instead, we included young adults with NDCs > 18 years and carers of children with NDCs, and further research is proposed to ensure the voices of young people < 18 years with NDC are captured in a more meaningful and thorough manner.

4.5 Future Directions

Proposed next steps include the finalising and piloting of a tool, based upon the items that reached panel consensus. A first step is to test the tool within the education system. Feasibility and acceptability studies, including the voices of people with lived experience, are necessary to evaluate the tool's utility. Further investigation needs to occur into how to use the ideas on improvements in transition services from this expert panel to adapt and redesign services across Aotearoa, New Zealand. Both the transition tool and ideas for service improvement mirror the broad and holistic approaches proposed in the New Zealand Disability Strategy 2016–2026 [27], providing incentive for a review of transition services during this critical period for young people as they transition from paediatric into adult services.

5 Conclusion

Transition from paediatric to adult services is a journey requiring close collaboration between the young adult, family/whānau and the multidisciplinary team to ensure a smooth and efficient process. This approach leads to empowerment and enables young adults to begin to manage and/or participate more in their own care and wellbeing and achieve better long-term health outcomes. This study provides direction on key domains related to transition services and creation of a new transition tool for young adults with NDCs in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Adaptation and improvement of transition services, including the tool, will ensure a more organised, personalised, safe, equitable and holistic transition process contributing to improved long-term health outcomes for young people with NDC.

Author Contributions

Yattheesh Thanalingam: writing – review and editing, writing – original draft, visualisation, project administration, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualisation. Fiona Catherine Langridge: writing – review and editing, writing – original draft, visualisation, project administration, methodology, validation, supervision, project administration, conceptualisation. Jin Russell: writing – review and editing, visualisation, project administration, methodology, supervision, conceptualisation. Anita Johansen: writing – review and editing, visualisation, project administration, supervision, conceptualisation. Rachel Howlett: writing – review and editing, visualisation, conceptualisation. Colette Muir: writing – review and editing, visualisation, project administration, methodology, supervision, project administration, conceptualisation.

Acknowledgements

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley—The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the University of Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to enrolling in the panel.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Description | Total N = 62 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 15 (24.2) |

| Female | 47 (75.8) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 years | 1 (1.6) |

| 25–34 years | 15 (24.2) |

| 35–44 years | 17 (27.4) |

| 45–54 years | 22 (35.5) |

| 55–64 years | 5 (8.1) |

| 65–74 years | 1 (1.6) |

| 75 years or above | 1 (1.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| European | 34 (54.8) |

| Māori | 12 (19.4) |

| Asian | 11 (17.7) |

| Pacific | 1 (1.6) |

| Middle Eastern/African/Latin American | 4 (6.5) |

| Role in care for young adults with neurodevelopmental conditions | |

| Medical doctor | 30 (48.4) |

| Allied health professional | 3 (4.8) |

| Allied health professional + educator | 8 (12.9) |

| Allied health professional + research/advocacy | 1 (1.6) |

| Allied health professional + research/advocacy + caregiver | 1 (1.6) |

| Allied health professional + caregiver | 1 (1.6) |

| Nurse | 4 (6.5) |

| Nurse + caregiver | 2 (3.2) |

| Educator | 3 (4.8) |

| Educator + research/advocacy | 1 (1.6) |

| Educator + Caregiver | 1 (1.6) |

| Research/Advocacy | 5 (8.1) |

| Research/advocacy + caregiver | 2 (3.2) |

| Years of experience in profession | |

| 1–5 | 5 (8.1) |

| 6–10 | 26 (41.9) |

| 11–15 | 14 (22.6) |

| 16–20 | 5 (8.1) |

| 21–25 | 3 (4.8) |

| 26 years or greater | 9 (14.5) |

| Work setting | |

| Community | 26 (41.9) |

| Community + hospital | 16 (25.8) |

| Rural | 1 (1.6) |

| Hospital | 19 (30.7) |

| District Health Board | |

| Auckland | 12 (19.4) |

| Waitemata | 5 (8.1) |

| Counties Manukau | 8 (12.9) |

| Capital and Coast | 2 (3.2) |

| Waikato | 21 (33.9) |

| Not applicable | 14 (22.6) |

| Professionals with personal or lived experience of neurodevelopmental conditions | |

| Lived experience of neurodevelopmental disability/condition | 2 (3.2) |

| Parent of a person with a neurodevelopmental disability/condition | 7 (11.3) |

| No personal or lived experience | 53 (85.5) |

| Years involved with the care of children with neurodevelopmental conditions/disabilities in general | |

| Less than 1 year | 3 (4.8) |

| 1–5 years | 15 (24.2) |

| 6–10 years | 18 (29.0) |

| 11–15 years | 8 (12.9) |

| 16–20 years | 6 (9.7) |

| 21–25 years | 3 (4.8) |

| 26 years or greater | 8 (12.9) |

| Themes: ideas for a transition tool | Selected quote |

|---|---|

| General principles | ‘I just want to add that it isn't as easy as a checklist. It's around informed consent and informed knowledge, this should be something that is reviewed a few times during transition, and need to involve them in practical real-life examples to help with a further understanding for either them or their whānau’. |

| Communication |

‘I remember this 5-min phone handover between a physiotherapist saying my kid is going to turn 16 and will be referred to the adult team—that was it—no introduction, no clear plan—and 6 months later we were still waiting to touch base with the adult team’. ‘There was limited handover from the paediatrician to the GP—all it was a letter summarising key events and recommendations for care’ I don't get how this is substantial enough and of course the poor GP has to scramble to find ways to action all of these grand plans—Years of work wasted I feel as these children don't get the continuity of care, they so deserve. |

| Healthcare management | ‘I feel the care that my child receives is solely dependent on the effort that my partner and I put in. I find a constant need to plan/liaise with various departments in order to get services put in place. If I am not proactive in planning the next steps, then nothing happens as agencies do not aid in progressing care for these children. I am in a position of privilege as I work in the healthcare setting and am able to sieve through the huge barriers there are to accessing care (eligibility criteria)—but for parents that who are not in the healthcare setting this may be even more difficult/not possible at all. Who ends up suffering are these kids really’. |

| Rights |

‘Importance of understanding confidentiality and for young people to have the opportunity to be seen alone without their parents’ ‘I believe overall that young adults and families need to learn about the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and how they can use this to advocate for changes to happen’. |

| Activities and engagement | ‘Adult services are very disconnected compared to what is available in the paediatric setting—I feel that adult services are too isolated—if only there were facilities/activities/services that was more integrative and all encompassing—I feel this will make a huge difference to the care we provide’. |

| Supports and community connectedness |

‘I feel there needs to be a new model—one which puts the child and wellbeing of their family at the centre of attention—rather than focusing on criteria/checklist’ ‘Also to tell the individual young people who the Disabled Peoples's Organisation are and that they can join those groups ie Disabled People Assembly—pan disability group and People First—for learning (intellectual) disability’. ‘Having sufficient cultural support for young people and their whānau to feel safe and looked after in the medical system, so that they can continue to be supported in that system’ |

| Whānau/family |

‘This is very aligned with Whānau Ora approaches, but a bit more detailed’ Clear pathways with a single point of contact to a multidisciplinary team important. Parent and whānau inclusion important |

| Culture |

‘Cultural Identity: Connections to land and culture, big picture influences, collective well-being—Mana Taiohi’ ‘Culture maintenance: Ensuring people have access to, and considerations of their cultural systems/communities/beliefs’ ‘There is no recognition and understanding of one's cultural and personal values nor is there any consideration of parents and family views and their needs for their child’ |

| Mental and spiritual health | ‘Mental health is an important consideration for these young adults with NDD and their parents in the transition process—we need to acknowledge it is a stressful time for all involved—For a child with NDD it can exacerbate existing mental health struggles with loneliness and neglect—leading to more serious implications as an adult—as advocates we need to continue finding ways of easing the burden/simplifying pathways to ensure care is given appropriately- there ware tools out there—there needs to be better implementation’. |

| Sexual health | ‘The topic of contraception—whilst controversial—should be broached if it is deemed the young disabled person may be engaging in sexual activity. This is of course their right, so supportive information on decision making, the right to say “no” and the norms of dating behaviour might be useful. This would hopefully help prevent unwanted sexual contact or abuse’. |

|

Themes: Ideas for Supporting Transition |

|

| Processes |

‘There is certainly fear of the uncertainty, and a certain element of hopelessness considering us parents face a constant daily battle with health authorities to get the care our child deserves’ ‘There needs to be a clearly defined and standardised referral pathway—as long as the pathway is effective and helpful. The pathway ensure that child/needs of whānau are met—essentially a tailored approach’ |

| Resources |

Our paediatrician was amazing in guiding us/referring us to appropriate service- there were so many resources—when we learned about the adult services offered, we were extremely let down as there was nothing—everything was an hour drive away—everything was a new referral. This makes the idea of continuing care our paediatrician in private a very plausible idea. ‘We have been meeting with private PTs as we feel that the public services are too disjointed and overstretched to care for our 2 children—heaps of red tape and frustration in engaging with health services make this the only realistic option for us sadly’ ‘We have been doing private SLT and PT for our child—This cost us heaps of money monthly but I feel that the restrictions on who qualifies for care is a massive impediment to accessing anything’ |

| Professionals | ‘As clinicians we definitely need to listen and seek help from those that are impacted by NDD/caregivers lead the way in terms of making adult services more accessible—there has to be a way’ |

| Role of the General Practitioner |

‘There was limited handover from the paediatrician to the GP—all it was a letter summarising key events and recommendations for care I don't get how this is substantial enough and of course the poor GP has to scramble to find ways to action all of these grand plans—Years of work wasted I feel as these children don't get the continuity of care they so deserve’. ‘GPs are so busy that they do not have the time or headspace to comprehend with the needs of these children with NDDs’. ‘Our GP has been the one constant source of contact for us—but he was mostly putting band aids over large gaping wounds—no real understanding of how to engage/liase with services to progress care’. |

| Governance and systems |

‘There is red tape to everything—every call to community services ends up with a dead end and as a parent of a child with autism that requires increased care this is disappointing’ Adult services are very disconnected compared to what is available in the paediatric setting—I feel that adult services are too isolated—if only there were facilities that was more integrative and all encompassing—I feel this will make a huge difference to the care we provide |

| Culture |

‘There is a lack of cultural awareness in engaging with services—I feel that current service providers don't take the time to engage with family—to find out what is important to them—It's a one size fits all approach—after all we have been the main carers for the past 15 years. This makes us hesitant to engage with health services’ ‘National services may be challenging at an Iwi level as each Iwi may have different tikanga. Consolation with Iwi would facilitate this being done with the correct tikanga’ |

| Principles | ‘I feel there needs to be a new model- one which puts the child and wellbeing of their family at the centre of attention’ |

| Statements | N (%) | Median | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | Interquartile range (IQR) | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Processes | ||||||

| 1.1. Early transition planning. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.56 | 0.62 | 1 | ✓ |

| 1.2. Clarity around who will continue care for young adult. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.59 | 0.59 | 1 | ✓ |

| 1.3. Inclusion of the young adult in planning. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.64 | 0.63 | 1 | ✓ |

| 1.4. A clearly defined and standardised referral pathway. | 53 (85) | 5 | 4.48 | 0.74 | 1 | ✓ |

| 1.5. Flexible clinical encounters including appointment timings, home visit options and adaptable clinical environments. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.62 | 0.58 | 1 | ✓ |

| 1.6. Prioritise a whānau/community approach as opposed to an individualistic approach. | 56 (90) | 5 | 4.55 | 0.70 | 1 | ✓ |

| Theme 2: Resources | ||||||

| 2.1. Provision of information on services and contact details. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.61 | 0.55 | 1 | ↑ |

| 2.2. Sharing and accessibility of information and documentation. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.53 | 0.67 | 1 | ✓ |

| 2.3. An individualised transition plan and summary. | 57 (92) | 5 | 4.53 | 0.69 | 1 | ✓ |

| 2.4. Provision of a health passport for the young person to carry with them. | 58 (94) | 4 | 4.42 | 0.62 | 1 | ✓ |

| 2.5. Access to a helpline for support when needed. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.47 | 0.62 | 1 | ✓ |

| 2.6. Transition resources which are co-designed with young people with neurodevelopmental conditions. | 57 (92) | 5 | 4.52 | 0.65 | 1 | ✓ |

| Theme 3: Professionals | ||||||

| 3.1. A transition coordinator for each young adult and their whānau. | 57 (92) | 5 | 4.53 | 0.65 | 1 | ✓ |

| 3.2. A dedicated transition team. | 54 (87) | 5 | 4.56 | 0.76 | 1 | ✓ |

| 3.3. Multidisciplinary collaboration between paediatric and adult services—e.g., health services, social services, schools. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.71 | 0.55 | 0.75 | ↑ |

| 3.4. Access to peer support navigators or support staff. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.56 | 0.62 | 1 | ✓ |

|

3.5. Continual education for adult health service professionals regarding current best transition practices. |

57 (92) | 5 | 4.61 | 0.69 | 1 | ✓ |

| Theme 4: Role of the general practitioner (GP) | ||||||

| 4.1. GP to be more equipped in terms of funding, training and exposure. | 36 (22) | 4 | 3.87 | 0.98 | 2 | 2 X |

| 4.2. GP to form bonds and maintain good relationships with whānau through regular follow ups. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.68 | 0.65 | 0.75 | ↑ |

| 4.3. Continuous communication between GP, young adult and whānau during transition period. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.76 | 0.50 | 0 | ↑ |

| 4.4. GP practices to be flexible, providing improved access and additional supports. | 38 (61) | 4 | 3.97 | 1.04 | 2 | X |

| Theme 5: Governance and systems | ||||||

| 5.1. Advocacy for more equity and access for whānau. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.60 | 0.56 | 1 | ↑ |

| 5.2. Dedicated youth transition leadership strategies and structures within district health boards. | 43 (87) | 5 | 4.37 | 0.75 | 1 | ✓ |

| 5.3. Educating young adults and whānau on law and legal rights. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | ✓ |

| 5.4. Practices in alignment with Ti Tiriti o Waitangi. | 57 (92) | 5 | 4.60 | 0.69 | 1 | ✓ |

| 5.5. Creation of a nationwide transition service to ensure uniformity and consistency of services. | 38 (62) | 4 | 3.90 | 1.04 | 2 | X |

| Theme 6: Culture | ||||||

| 6.1. Support cultural identity and needs. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.66 | 0.51 | 1 | ↑ |

| 6.2. Incorporate cultural frameworks such as Mana Taiohi, Te Whare Tapa Whā, Meihana and Te wheke. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.48 | 0.62 | 1 | ✓ |

| 6.3. A by Māori for Māori approach. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.47 | 0.62 | 1 | ↑ |

| 6.4. Tikanga Māori worldview model of healthcare. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.60 | 0.66 | 1 | ✓ |

| 6.5. Consideration of the effects of structural forces such as racism and marginalisation. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.56 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| Theme 7: Principles | ||||||

| 7.1. Principle of Whānaungatanga—building and sustaining trusting quality relationships. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.73 | 0.55 | 0 | ✓ |

| 7.2. Principle of Manākitanga—Nourishing the collective wellbeing of connected communities. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.53 | 0.56 | 1 | ↑ |

| 7.3. Principle of Whai Wāhitanga—participation, the ability for young people to assume agency, take responsibility. | 55 (89) | 5 | 4.52 | 0.70 | 1 | ✓ |

| 7.4. Principle of Matauranga—sources of truth, health information from a holistic perspective. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.61 | 0.63 | 1 | ✓ |

| 7.5. Principle of Whakapapa—connections to the land and people. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.68 | 0.50 | 1 | ↑ |

| 7.6. Principle of Hononga—identify and strengthen connections and Te ao (big picture influences, colonisation). | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.58 | 0.67 | 1 | ✓ |

| 7.7. Principle of Mana — All principles combined to promote and maintain the young person's pride and identity. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.71 | 0.46 | 1 | ↑ |

- Note: Round two items reaching consensus, not reaching consensus and reaching strong consensus > 95%. ✓ indicates consensus and ↑ indicates strong consensus. 5-point Likert scale for each domain as described above (1 = very unimportant, 2 = unimportant, 3 = neither unimportant or important, 4 = important, 5 = very important).

| Statements | N (%) | Median | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | Interquartile range (IQR) | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: General principles | ||||||

| 1.1. Supports for communication and capabilities: talking about my health and making healthcare decisions. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.73 | 0.52 | 0 | ↑ |

| 1.2. Healthcare transition and transfer: managing my healthcare appointments, medication, and treatments. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.53 | 1 | ↑ |

| 1.3. Activities and engagement: participating in activities at home, in my community. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.73 | 0.45 | 1 | ↑ |

| 1.4. Relationships and wellbeing: having healthy relationships and feeling supported. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.71 | 0.52 | 0.75 | ↑ |

| 1.5. Confirmation the information has been communicated with, received and transferred to the Department at the DHB or GP responsible for managing the adult. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.65 | 0.52 | 1 | ↑ |

| 1.6. Ensure checklist is reviewed by experts with a diverse range of ethnic and cultural background and expertise. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.60 |

0.49 |

1 | ↑ |

| Theme 2: communication | ||||||

| 2.1. Access and use of a health passport. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.56 | 0.53 | 1 | ↑ |

| 2.2. Use of visual aids during consultation such as play mats. | 53 (85) | 5 | 4.45 | 0.82 | 1 | ✓ |

| 2.3. Familiar with names of service providers and contact details (doctors, allied health) — know who to contact if need help. | 56 (90) | 5 | 4.63 | 0.71 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| 2.4. Communicate decisions/individual health needs to service providers. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.77 | 0.42 | 0 | ↑ |

| 2.5. Identify and alert other people about specific verbal/sensory triggers. | 57 (91) | 5 | 4.66 | 0.77 | 0 | ✓ |

| 2.6. Seek help from a trusted person not able to understand a healthcare decision. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.64 | 0 | ✓ |

| 2.7. Access to augmentative and alternative communication systems. | 55 (89) | 5 | 4.58 | 0.82 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| Theme 3: Healthcare management | ||||||

| 3.1. Navigation of the health system- keeping track of healthcare appointments, booking in appointments. | 54 (87) | 5 | 4.61 | 0.80 | 0 | ✓ |

| 3.2. Taking medication safely and on time (including recognising side effects and adverse drug reactions). | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.77 | 0.46 | 0 | ↑ |

| 3.3. Equipment management (wheelchair, orthotics, G-tube, CPAP machine). | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.62 | 0.61 | 1 | ↑ |

| 3.4. Organising health information (letters, prescriptions). | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.66 | 0.57 | 1 | ✓ |

| 3.5. Ensuring young adult and whānau has access to a GP. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.81 | 0.44 | 0 | ↑ |

| 3.6. Knowing when to seek help if sick or hurt or needing assistance. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.46 | 1 | ↑ |

| 3.7. Organise transport to get to healthcare appointments — walk, public transport, drive, etc. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.66 | 0.68 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| 3.8. Knowing how to apply for disability services/funding. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.79 | 0.45 | 0 | ↑ |

| 3.9. Make decisions about own health and wellbeing — knowing how to apply for disability services/funding. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.71 | 0.46 | 1 | ↑ |

| Theme 4: Rights | ||||||

| 4.1. Understands informed consent and the implications of informed consent. | 54 (87) | 5 | 4.45 | 0.80 | 1 | ✓ |

| 4.2. Understands health and disability rights. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.50 | 1 | ↑ |

| Theme 5: Activities and engagement | ||||||

| 5.1. Activities of daily living- washing, exercise, eating, dressing. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.76 | 0.43 | 0 | ↑ |

| 5.2. Self-cares for health including brushing teeth, menstruation. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.82 | 0.39 | 0 | ↑ |

| 5.3. Self-management in the community (including finances, shop). | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.71 | 0.46 | 1 | ↑ |

| 5.4. Keeping safe online, fraud, theft, exploitation. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.77 | 0.46 | 0 | ↑ |

| Theme 6: Supports and community connectedness | ||||||

| 6.1. Access and availability to adult specialist services that provide counselling, respite care, mental health services, equipment support and behaviour support services. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.77 | 0.46 | 0 | ↑ |

| 6.2. Access to social services for transport, housing and residential services and financial support, e.g., WINZ. | 57 (91) | 5 | 4.82 | 0.50 | 0 | ✓ |

| 6.3. Continuing education options and continuous professional development. | 58 (94) | 5 | 4.79 | 0.55 | 0 | ✓ |

| 6.4. Access to needs assessment with NASC. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.63 | 0.58 | 1 | ✓ |

| 6.5. Having a supportive social network (friends, family, colleagues). | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.56 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| 6.6. Access to vocational training, community-based programmes, employment opportunities, activities to nurture skills interests and abilities — outside of the health setting. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.84 | 0.37 | 0 | ↑ |

| 6.7. Familiarity with equipment needs and what equipment will be needed in the future. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.69 | 0.50 | 1 | ↑ |

| 6.8. Support with social interactions- places to interact with community. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.58 | 0.59 | 1 | ✓ |

| Theme 7: Whānau | ||||||

| 7.1. Health literacy/resources/past experiences of whānau. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.79 | 0.41 | 0 | ↑ |

| 7.2. Respite options for whānau. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.85 | 0.40 | 0 | ↑ |

| 7.3. Clarifying the role/involvement in whānau as a young adult begins transition to adulthood. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.77 | 0.42 | 0 | ↑ |

| 7.4. Utilising whānau community support and connections. | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.73 | 0.58 | 0 | ↑ |

| Theme 8: Culture | ||||||

| 8.1. Language needs associated with translation-translated documents, interpreters. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.81 | 0.51 | 0 | ✓ |

| 8.2. Access to appropriate cultural support. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.81 | 0.44 | 0 | ↑ |

| 8.3. Support with iwi tikanga. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.76 | 0.47 | 0 | ↑ |

| Theme 9: Mental and spiritual health | ||||||

| 9.1. Managing self-wellbeing including knowing triggers of stress. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.85 | 0.36 | 0 | ↑ |

| 9.2. Learning how to cope with stress and how to minimise triggers of stress. | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.89 | 0.32 | 0 | ↑ |

| 9.3. Learning how to make a supportive network (friends, family, close contacts). | 62 (100) | 5 | 4.87 | 0.34 | 0 | ↑ |

| 9.4. Talking about personal mental health issues. | 59 (95) | 5 | 4.79 | 0.52 | 0 | ✓ |

| 9.5. Talking about spiritual health/wairua/faith-based issues. | 54 (87) | 5 | 4.55 | 0.72 | 1 | ✓ |

| Theme 10: Sexual health | ||||||

| 10.1. Counselling around sexual health, sexuality (talking about my body, sex and relationships with people I trust). | 60 (97) | 5 | 4.73 | 0.52 | 0 | ↑ |

| 10.2. Supportive information on decision-making — human rights, convention on the rights of a person with disability to young adult and whānau in regards to sexual health. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.76 | 0.47 | 0 | ↑ |

| 10.3. Talking about body, sex and relationships with people that I trust. | 61 (98) | 5 | 4.82 | 0.43 | 0 | ↑ |

- Note: Round two items reaching consensus, not reaching consensus and reaching strong consensus > 95%. ✓ indicates consensus and ↑ indicates strong consensus. 5-point Likert scale for each domain as described above (1 = very unimportant, 2 = unimportant, 3 = neither unimportant or important, 4 = important, 5 = very important).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.