A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Maternal Child Health Nurse Education Programme Using Moore’s Outcomes Framework for Continuing Medical Education

Funding: This work was supported by Royal Children's Hospital Education Hub.

ABSTRACT

Aim

Maternal Child Health Nurses (MCHN) play an integral role in child health in the community yet lack professional development opportunities. A tertiary hospital sought to fill this gap and developed an online MCHN education programme. This study aimed to assess the impact of the programme on MCHN confidence, knowledge and practice and to understand the factors influencing its impact.

Methods

MCHN enrolled in the programme were invited to participate in a mixed method study based on Moore's Outcomes Framework for continuing medical education. Quantitative data from surveys collected pre and post live webinars and at 6 months post programme implementation assessed participant knowledge and confidence, and the quality of the programme. Qualitative data from individual semi-structured interviews was analysed inductively to understand impact.

Results

Reported knowledge and confidence improved after each webinar (for knowledge from 2.60 out of 4 (95% CI 2.54–2.66) to 3.45 out of 4 (95% CI 3.40–3.59) post-webinar (p < 0.001) and for confidence from 2.58 out of 4 (95% CI 2.52–2.64) to 3.42 out of 4 (95% CI 3.38–3.47) post-webinar (p < 0.001)). Four themes emerged which facilitated the programme impact: filling a continuing education void, supporting diverse learning styles and needs, enhancing practice and advocacy through empowerment and fostering connections and respect.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that a well-designed online education programme led to increased knowledge, confidence and changes in practice. It facilitated connection and respect and reinforced MCHN value and contribution. It highlighted and addressed an educational gap within the MCHN continuing education landscape and has proven to be sustainable and impactful.

Summary

-

What is already known about this topic

- ○

Maternal Child Health Nurses (MCHN) play an essential role in providing health care in the community.

- ○

MCHN require relevant and ongoing education to ensure up to date and safe patient care.

- ○

Communities of practice provide safe environments for health professionals to learn from colleagues and experts.

- ○

-

What this paper adds

- ○

An online multifaceted, spaced and relevant education programme designed for MCHN improved knowledge and confidence, changed clinical practice and filled a continuing education void—while creating a sense of personal and organisational connection.

- ○

A collaborative design for an education programme that includes spaced synchronous and asynchronous education, with the opportunity to ask questions and reflect on practice, can foster the development of a Community of Practice and enhance educational outcomes.

- ○

Development of an education programme specifically for MCHN fostered a sense of value, respect and acknowledgement and improved empowerment, while catering for a variety of learners at different levels of clinical experience.

- ○

1 Introduction

In the state of Victoria, Australia, Maternal Child Health Nurses (MCHN) play an essential role in providing health care and education for children and their families in the community [1]. Their practice includes monitoring early childhood health and development and parent education in community-based health centres. Acute assessment, referral and education are provided by MCHN on the 24-h MCHN telephone service. MCHN are frequently the first community health professional a newborn child and family will see, and this relationship will continue until the child enters school.

The MCHN scope of practice has expanded from monitoring children's growth and development to managing complex family circumstances that require an advanced understanding, to ensure optimal care and positive health care outcomes [1]. MCHN practice independently and collaborates with other healthcare professionals to ensure the health needs of the child are met [1]. Victorian MCHN must complete 40 h each year of continuing professional development [2]. To ensure they are up to date, they require ongoing, relevant and evidence-based professional development to maintain and grow expertise [3].

Effective professional development activities should be based on assessed needs, include interactive activities that engage learners and apply a multifaceted approach that combines several different interventions [4]. Evidence demonstrates that knowledge retention is enhanced when learning sessions are spaced [5, 6] and relevant for health professional education [7]. Communities of Practice (CoP) [8, 9] offer a promising format for education and have been described as informal ‘learning communities’ [10, 11], which can provide a safe environment for individuals to engage in learning through observation, interaction with experts and discussions with colleagues [12]. Technology has enabled CoPs to be formed based on common interests, not restricted by geographical locations [12]. Furthermore, the virtual CoP model is more fluid than traditional CoPs.

Based on these educational concepts, an online MCHN Paediatric Health Education Programme was designed incorporating content identified as gaps by MCHN. It was delivered by a tertiary paediatric hospital to which MCHN refer, and which provides clinical practice guidelines and patient information utilised by MCHN. The education delivery was based on a CoP with spaced learning, interactive and multifaceted activities—including monthly webinars, an online chat forum, online resources, and feedback to continually inform programme development. The 12-month online learning programme was delivered from July 2022 to June 2023, including 10 live webinars presented by clinician experts. The topics were based on a gap analysis conducted by the research team with its external collaborators, including MCHN leaders, using data from the maternal and child health help line regarding common presentations, with feedback from MCHN themselves and co-design discussions. Topics included the unwell child, newborn rashes, developmental hip dysplasia, immunisation, common childhood illnesses, tongue tie, dentistry, infant feeding, burns, inguinal hernia and hypospadias. The programme's virtual platform consisted of the recorded webinars, online forums and a resource folder for each webinar topic.

The aims of this research were to assess the impact of the education programme on participant confidence, knowledge and practice and the factors influencing programme outcomes.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

We conducted a mixed methods evaluation of the education programme utilising qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (surveys) methods. Our research design was based on a community health need (strengthening care of children in the community). It was informed by Moore's expanded conceptual framework for designing and assessing continual medical education, which articulates learning outcomes at seven levels: participation, satisfaction, learning, performance, patient health and community health [4, 13].

Ethics approval was granted by The Royal Children's Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 87268).

2.2 Participants

About 895 MCHN enrolled in the 1-year education programme were eligible to participate in the research study.

2.3 Data Collection

Quantitative data was obtained from online surveys via a QR code accessible pre- and post- each live webinar, to assess the knowledge and confidence of participants on the specific webinar topics. Six months into the programme, participants were sent an email with an invitation via a QR code to complete an online structured survey to assess the programme format, content and value, and impact on participants' confidence, knowledge (learning) and clinical practice (competence/performance). At this survey's completion, participants were asked to opt in to an individual interview, for which they gave written consent. Interviews were based on a semi-structured guide to explore participant perception of participation, satisfaction, learning, practice (competence/performance) and patient health, alongside the factors which influenced outcomes. Interviews took, on average, 20 min and were conducted by a single researcher. Interviews continued until no new themes emerged.

2.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics, including the number and percentage of participants responding in each category or where relevant, the mean and 95% CI. Mean knowledge/confidence ratings pre- and post-webinars were compared using a paired t-test.

Qualitative data from the interviews were analysed using inductive content analysis [14]. Inductive content analysis was used to ensure the themes generated were practical for programme improvement and understanding and to avoid assumptions about the programme's success. Coding was conducted in an iterative process—first completed by one independent researcher, then reviewed by the research team for agreement. As further interviews were analysed, codes were refined and reviewed at intervals, and finally the research team agreed collectively on the themes that emerged.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative Data

About 895 MCHN enrolled in the programme, from metropolitan, regional and rural locations. There was a total of 1251 responses to the pre (520) and post (731) webinar surveys. Topics were felt to be highly relevant to practice, with half of respondents (59%) in the pre webinar survey stating that webinar topics were encountered in work at least weekly and 25% reporting encountering topics at least monthly.

There was a significant improvement in reported knowledge of the education topics after each webinar, with improvement in the mean self-rated knowledge scores from 2.60 out of 4 (95% CI 2.54–2.66) pre-webinars to 3.45 out of 4 (95% CI 3.40–3.59) post-webinars (p < 0.001). Similar improvements were seen in mean ratings of confidence scores, improving from 2.58 out of 4 (95% CI 2.52–2.64) to 3.42 out of 4 (95% CI 3.38–3.47) post-webinars (p < 0.001).

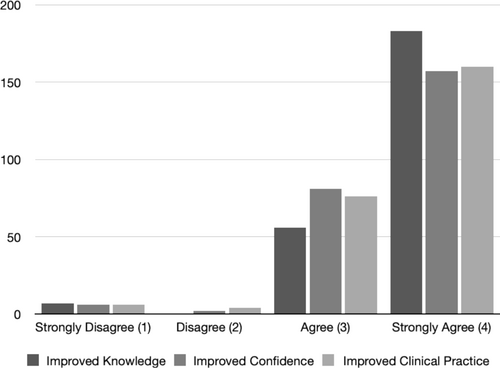

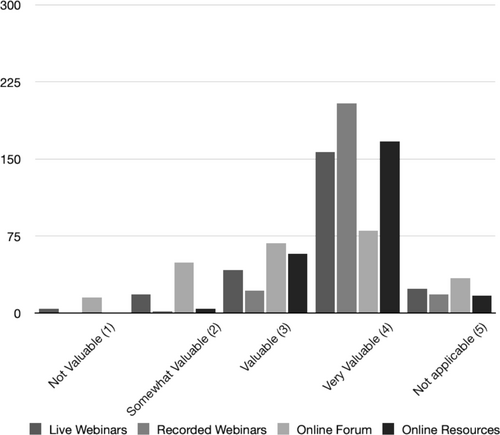

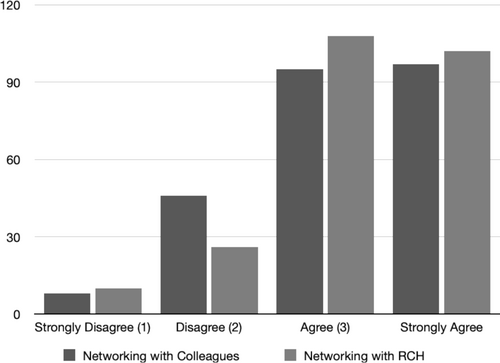

About 246 MCHN (27%) responded to the survey 6 months post-programme implementation. Almost all ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the programme positively impacted their knowledge and confidence and improved their clinical practice (Figure 1). Participants were asked to rate the value of different programme components (Figure 2). While the majority valued all components, access to recorded webinars and online resources was valued most. The majority ‘strongly agreed’ that the webinars held their interest, and the education was relevant to their practice. The majority ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that participation in the programme provided them with professional links or networks with colleagues and the hospital (Figure 3). All agreed they would participate in the programme again and few (10%) suggested changes to the programme.

3.2 Qualitative Interviews

A 22 participants (P) consented to an interview, and 16 interviews were conducted. Table 1 summarises their experience, role, and work location. The analysis revealed four overarching themes, described below with supporting quotes in Table 2.

| Total | 16 |

| Experience—Experienced (> 5 years of MCHN practice) | 13 |

| Experience—New (< 5 years of MCHN Practice) | 3 |

| Work setting | |

| Clinics with solo MCHN practitioner | 4 |

| Clinics with multiple MCHN practitioners | 9 |

| MCHN phone line | 1 |

| Safer Care Victoria MCHN Lead | 1 |

| Higher education (university lecturer) | 1 |

| Work location | |

| Metropolitan | 11 |

| Regional/rural | 5 |

| Themes | Sample quotes (participant number in brackets) | Quote number |

|---|---|---|

| Filling an education void |

|

Q1 |

|

|

Q2 | |

|

|

Q3 | |

| Supporting diverse learning needs |

|

Q4 |

|

|

Q5 | |

|

|

Q6 | |

|

|

Q7 | |

|

|

Q8 | |

| Enhancing MCHN practice and advocacy through empowerment |

|

Q9 |

|

|

Q10 | |

|

|

Q11 | |

|

|

Q12 | |

|

|

Q13 | |

|

|

Q14 | |

| Fostering connections and respect |

|

Q15 |

|

|

Q16 | |

|

|

Q17 | |

|

|

Q18 |

3.2.1 Theme 1: Filling an Education Void

Participants universally acknowledged that the programme addressed a significant educational gap within the MCHN continuing education landscape and emphasised the need for the programme to be sustained. Participants described limited continuing education for MCHN and that this programme bridged the gap between previous learning and current practice (Table 2, Q1). Participants expressed a common desire for the programme's continuation to maintain up-to-date and uniform education for MCHN (Table 2, Q2 and Q3).

3.2.2 Theme 2: Supporting Diverse Learning Needs

Participants appreciated the programme's capacity to support their learning journeys, irrespective of their experience levels and practice settings. For MCHN practising in isolation, the programme served as a useful support for best practice and continuing professional development (Table 2, Q4).

The programme's digital delivery model significantly improved accessibility, reducing the need for travel and minimising disruption to the workday. Features such as interactive polling systems and the availability of synchronous and asynchronous content facilitated an engaging, self-paced learning environment (Table 2, Q5).

Participants highlighted the benefits of interactive and on-demand content, emphasising the value of being able to engage actively with the material and revisit it as needed (Table 2, Q6 and Q7).

Participants reflected that the scheduling at the beginning of the workday and the delivery of concise education sessions encouraged employer support for MCHN participation, including the allocation of work time, financial support for enrolment, with local leadership facilitating participation (Table 2, Q8).

3.2.3 Theme 3: Enhancing MCHN Practice and Advocacy Through Empowerment

Participants expressed feeling empowered by the practical knowledge acquired from the programme, which facilitated immediate application in their practice and enhanced communication with parents (Table 2, Q9). Participants described specific changes in practice for better outcomes (Table 2, Q10). For others, the benefit was not necessarily change but validation of practice (Table 2, Q11).

The expertise and credibility of clinician presenters were pivotal in enhancing participants' confidence in their knowledge base and ability to access evidence-based information in their field (Table 2, Q12).

Empowered with increased knowledge and confidence, participants reported being better positioned to advocate effectively for the needs of families and make informed clinical decisions and referrals. Some participants described how the programme bolstered their confidence in providing anticipatory guidance, making informed recommendations and referencing the programme to support their advice to parents (Table 2, Q13).

One participant described the programme enabling advocacy for a child to receive critical and timely intervention (Table 2, Q14).

3.2.4 Theme 4: Fostering Connections and Respect

The programme contributed to fostering a sense of community among MCHN, offering opportunities for engagement, shared learning and discourse, thereby enriching their professional relationships. Some participants shared how the programme enabled collective viewing and discussion of webinars, enhancing team cohesion and stimulating professional conversations (Table 2, Q15).

Participants felt the programme provided a pivotal link to the tertiary paediatric hospital, enhancing their understanding of hospital processes and resources, thus enabling more informed patient referrals and care. Some participants described how the programme improved their connectivity and familiarity with hospital operations, facilitating better patient care (Table 2, Q16).

Participants reported feeling valued, seen and respected through their programme, and that their expertise and the importance of their role in paediatric healthcare were acknowledged (Table 2, Q17).

Some participants emphasised the respect and recognition received from the programme and its presenters, highlighting the positive impact on their professional identity and the broader MCHN service (Table 2, Q18).

4 Discussion

Our study demonstrates that a multifaceted, online year-long education programme targeted at identified gaps in MCHN learning needs had high participation and led to increased knowledge, confidence and changes in practice, with wider implications for empowering this workforce to achieve better patient outcomes. The programme provided a sense of community and cultivated a sense of value and respect. Empowerment through learning led to self-advocacy and advocacy for families in their care, demonstrating positive outcomes at all levels of Moore's Outcome Framework for professional development [4].

From the literature, a scoping review of the broad impacts of continuing professional development for health professionals highlighted a similar range of outcomes among studies [15]. However, the review emphasised that impacts on knowledge and confidence are more commonly measured, while those relating to personal or organisational change described in our research (such as empowerment, intent to change practices or network building) are less common. A rapid evidence review of factors optimising professional development for nurses highlighted motivation, relevance to practice, availability of workplace learning and strong enabling leadership [16]. Each of these is evident in our findings.

Part of our programme's success was addressing an ‘educational void’ articulated by participants, which thus provided motivation. This concept has been noted as a factor influencing success in other education programmes [17]. Effective learning design was critical to supporting diverse learning needs for professionals working in different settings at different levels of competence in their own workplace [18]. While leadership was provided through the programme coordination centrally, it was demonstrated by the findings to be critical in the local workplace to enable engagement. The online design aimed to achieve scale and address challenges of practicing in isolated settings, and the findings provide examples of how the programme fostered self-directed or peer learning and maintained an interactive experience in the virtual environment. Additional learning theories or frameworks have been highlighted in the literature as relevant to online continuing professional development and its ability to transfer learning to practice [18]. They are evident in action in our programme outcomes—such as Self-Determination Theory (affording flexibility and choice in how to engage) [19], Practical Inquiry Model (embedding opportunities for reflection and interaction) [20] and Virtual CoP [21].

The use of quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate the programme and look across different outcome level's according to Moore's framework are strengths of this study, having been highlighted as needed in previous reviews [15]. There is the potential for response bias in that those who responded may be more favourable towards the programme. In addition, the evaluation only captures the programme at 1 year, and with an ongoing programme planned there is an opportunity to gain more meaningful data on outcomes at patient and community levels.

5 Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that a well-designed online learning programme led to increased knowledge, confidence and changes in practice. It facilitated a sense of connection and respect among MCHN and the tertiary paediatric hospital, empowering improvement in care. The programme highlighted and addressed a significant educational gap within the MCHN continuing education landscape and offers a model for other health professional education needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Royal Children’s Hospital Education Hub for their support and funding the education programme, and support of the research. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley - The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was granted by The Royal Children's Hospital Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC 87268).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.