Fabricated or induced illness in children: A guide for Australian health-care practitioners

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Abstract

Many paediatricians have, or will have at some time in their career, a child under their care who has, or is suspected to have, Fabricated or Induced Illness in a Child (FIIC). Often a pattern of investigation, treatment and referral develops, with things ‘just not quite adding up’ and the diagnosis of FIIC is not considered. How can Australian health-care practitioners better recognise and respond to concerns around fabricated or induced illness? When should concerns be reported to protective services? How should we talk to families when we suspect fabrication or induction of illness in their child, and what is the role of specialised forensic paediatric services in Australia in relation to such cases? FIIC is almost certainly not as rare as commonly perceived and it can be identified early. Although challenging, FIIC can be managed effectively with a thoughtful multidisciplinary team approach. This article aims to provide paediatricians with a strategy that will hopefully serve to raise awareness, facilitate earlier intervention and simplify the approach to management, encouraging the view that taking action need be no different to addressing any other complex paediatric problem.

In 2015, an editorial in this journal described induced illness in a child (often referred to as Munchausen by proxy) as ‘arguably the most confronting condition a paediatrician ever has to manage’ and highlighted the concern that highly competent paediatricians were turning a ‘blind eye’ to the problem.1 The diagnosis of Fabricated or Induced Illness in a Child (FIIC) is often viewed with trepidation by paediatricians who struggle with complex presentations under the time constraints of busy practice, and who are trained to trust information provided by parents, assumed to be acting in their child's best interest. In the setting of FIIC, paediatricians can be deceived, resulting in harm to the child.2, 3

It is likely that many paediatricians have, or will have at some time in their career, a child under their care who has, or is suspected to have, FIIC.4 All too often a pattern of investigation, treatment and referral develops, with things ‘just not quite adding up’. Many years may pass simply because FIIC was not explicitly considered within the differential diagnosis.5-7 So how can we better recognise and respond to these concerns? When should a report be made to protective services? How should we talk to families when we suspect FIIC in their child, and what is the role of specialised forensic paediatric services in Australia?

In this article, we suggest that FIIC is almost certainly not the rare ‘enigma’ that many believe it to be, that it can be identified earlier, and may then be managed effectively with a thoughtful multidisciplinary team approach. We aim to provide paediatricians with a strategy that we hope will serve to raise awareness, facilitate earlier intervention and simplify the approach to management, encouraging the view that addressing FIIC need be no different to addressing any other complex paediatric problem.

What is Fabricated or Induced Illness in a Child?

FIIC occurs when a child's care giver (typically the mother) elicits medical or psychological care for her child based on her need for the child to be recognised as more unwell or impaired than the child's actual state of health or wellbeing, resulting in actual or likely harm to the child.4, 6 The condition is almost certainly more common than has been previously acknowledged and understanding has been hampered by nomenclature, definitional, threshold and management challenges.4, 8-10

Since Meadow's 1977 description of ‘Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy’,11 our understanding of this complex condition has evolved and a broader conceptualisation of over-medicalization phenomena has developed, within which FIIC exists.5 In parallel, there has been an evolution of health, information technology and social support systems, an increase in public awareness of neurodevelopmental and other disorders, and an unprecedented expansion in access to information and social connectivity afforded by the Internet. These factors may have had the unintended consequence of increasing the incidence of FIIC.12 Although perceived to be a rare form of maltreatment, FIIC is almost certainly significantly under-recognised and under-reported.2, 4, 6, 13, 14 The experience of this group (authors 1 and 3) is that there has been a notable increase in referrals to the Victorian Forensic Paediatric Medical Service in Melbourne regarding FIIC. Greater recognition is a positive step, but condition severity leads us to wonder if these cases are merely the ‘tip of the iceberg’.

Where Does FIIC Fit in the Overmedicalisation Spectrum?

There has been a shift from focusing on the psychology and motivation of the carer to focusing on the harm caused to the child, as evidenced by nomenclature change over time. Terms such as Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy, Fabricated Disorder Imposed on Another (included in DSM-5), Paediatric Condition Falsified and Fabricated Disorder by Proxy reflect the mindset and actions of the abuser. Medical child abuse reflects the medical setting and the actions of professionals. Using the terms fabricated or induced illness (FII) or Fabricated or Induced Illness in a Child (FIIC) clearly and unambiguously shifts the focus onto the child's experience and the child as the victim of abuse rather than the abuser's psychology or motivation. Paediatricians can thus focus on FIIC as a paediatric diagnosis rather than a diagnosis made after considering and understanding the motivation of the adult care giver.2, 4 Focusing on harm to the child, without the need to prove caregiver deception or malintent, may simplify the diagnostic process and facilitate earlier recognition and intervention.

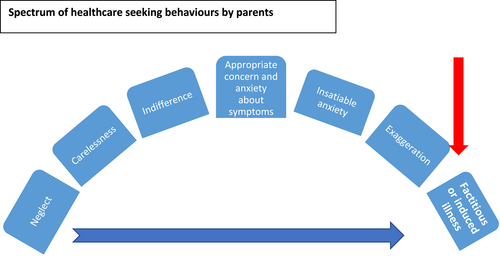

Paediatricians are familiar with the spectrum of health-care-seeking behaviour demonstrated by parents, ranging from neglect of children's medical needs to the exaggeration of signs and symptoms, falsification of information and induction of illness that can characterise FIIC (Fig. 1).

Over-medicalization or apparent over-medicalisation, including behaviours on the right hand side of this spectrum, can occur in a range of settings and for different reasons. FIIC should not be a diagnosis of exclusion and can be distinguished from other forms of over medicalisation by careful and thorough assessment (see Table 1):

| Carefully distinguish fabricated illness from… | Intervene by… |

|---|---|

| The over-anxious or misguided parent, genuine misunderstanding and unintentional misattribution | Reassuring, educating and redirecting parents – parents acknowledge and comply |

| The diagnostic dilemma | Identifying the rare medical diagnosis |

| The Medically Unexplained Symptoms (functional disorders, somatisation) | Collaborative work to achieve health, psychological intervention to manage symptoms driven by the child's anxiety or mental state – underlying factors are acknowledged by the parents |

| Malingering | Identifying a defined material gain or positive avoidance and acting to stop it continuing |

| Maternal delusional psychosis | Providing psychiatric assessment and treatment of carer |

| Over-anxious clinician or clinician unwilling to refuse parental request or unwarranted demand for tests, medication, completion of forms and referrals to specialists | Practising responsibly, ethically and having the courage to say ‘no’ when it is in the child's best interest |

The FIIC Triangle

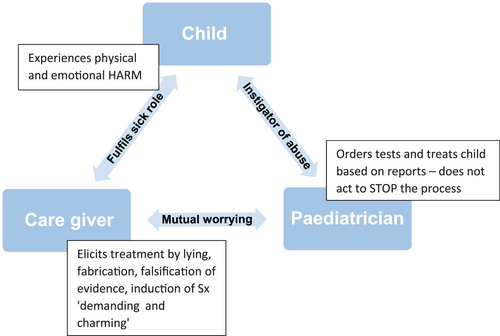

FIIC entails the pathological distortion of the therapeutic triangle (see Fig. 2).

The care giver elicits treatment by misrepresenting the child's condition (exaggerating, lying, falsifying evidence or inducing illness in the child, i.e. by deception). False information provided is inserted into medical decision-making causing paediatricians to order tests and treatments. A gap exists between the history presented and observations made in relation to illness or impairment, for example a care giver reports seizures but no seizures are independently witnessed and the child's electroencephalogram (EEG) is normal. This discordance can be conceptualised as a gap between information provided (the history) and independently verified evidence of illness or abnormality; a history to evidence gap. In many instances, despite feeling puzzled by the unusual course of the child's illness, the doctor continues to order investigations and interventions, thereby becoming complicit in perpetuating abuse and perpetrating harm. Traditional approaches to diagnosis such as pattern recognition may fail and ‘lock-in’ (anchoring on a diagnosis without subsequent adjustment to new information) can perpetuate diagnostic labels.13 Abusive care givers may seek out individual practitioners who accommodate their requests, strive to maintain patient satisfaction, hold concordant opinions or are prepared to act unconstrained by current evidence.13 Doubting a care giver who presents as being highly competent, professional and well-educated in medical terminology also requires overcoming overwhelming cognitive bias.

The child subjected to FIIC experiences physical harm as a result of undergoing unnecessary medical investigations, procedures or treatments, as well as significant emotional harm as a result of fulfilling the sick role, collusion, social isolation, the generation of and entrapment within a false belief system, confusion and anxiety. Victims may or may not be aware of the abuse, but because their wider social circle is usually similarly entrapped in the false belief of illness, the victims of FIIC have no safe place to escape. Long-term outcomes are poor if the condition is not recognised and treated early and FIIC has proved fatal.3, 16, 17

Children with underlying illness are over-represented as victims.4 Medical conditions commonly seen in this setting include gastrointestinal diseases, apnoea, seizures, allergies and recurrent fever. Behavioural, educational and neurodevelopmental conditions are being increasingly recognised in the setting of FIIC.18-20 It should never be assumed that a confirmed diagnosis excludes FIIC, noting that perpetrators who have a psychological need met by engaging with health professionals may begin with appropriate interactions and sick children may be more dependant and therefore vulnerable to victimisation.4, 13 Failing to appreciate this fact leads clinicians to evaluate solely for the presence or absence of disease rather than actively seeking evidence of fabrication or deception when further, and sometimes unexpected, concerns arise. An important misconception among clinicians is that disorders that could account for the child's signs and symptoms must be ruled out in order to make a diagnosis of FIIC.10

Almost all reported perpetrators of FIIC are women (98%) and the mother of the victim.3 A disengaged, geographically or emotionally absent father is typical. In nearly half of the cases, the perpetrator is employed in health care, though this figure may be exaggerated and a feature of pathological lying.3 A history of childhood maltreatment or personality disorder in the perpetrator may be elicited and fabricated disorder imposed on self has been reported in about a third of perpetrators – the well-being of children of individuals with fabricated disorder imposed on self, therefore, warrants particular attention.3

The care giver appears to derive psychosocial gain from the situation and the behaviour likely reflects an internal drive to satisfy a psychological need.4, 13 This may include a need for attention and sympathy (such as from friends, family or social media groups); a need to be viewed positively as a self-sacrificing martyr; a desire to manipulate professionals; a desire for excitement derived from engagement with the medical system; or to enable continued closeness to the child. The analogy of addiction has been referenced to describe the care giver's persistence in falsification despite the potentially dangerous consequences, their anger when challenged and the escalation of the behaviour over time.10, 13 Material gain (such as from NDIS packages or crowd funding) may help to externally validate erroneous and firmly held beliefs. A complex combination of situational and personality factors likely combine and the care giver may find themselves in a web of deceit and lies from which they cannot extract themselves.

A useful framework when considering the manner in which care givers cause harm is shown below (Table 2). Carers most commonly use their WORDS (e.g. exaggerating symptoms; falsely reporting illness; coaching the child to falsely report) and, less commonly, their HANDS as they engage with medical professionals to construct a narrative of the child's poor state of health.6

| Method of harm | Examples; use of WORDS | Examples; use of HANDS |

|---|---|---|

| Producing false information | False reporting of signs and symptoms, for example, seizures, vomiting or apnoea | Producing false documentation, for example, falsified clinic letters, forged signatures |

| Withholding information | For example, failing to disclose results of prior tests or interventions | |

| Exaggeration | Reporting more frequent or worse symptoms than actually exist | Overstating level of disturbance or impairment on forms such as behaviour and developmental checklists |

| Coaching | Of child, family members or spouses to falsely report | |

| Simulation | Misrepresenting, for example, urine/stool samples contaminated with carer's blood reported as coming from the child | |

| Induction | Creating symptoms or impairments – suffocating, starving, infecting, injuring, poisoning, covertly administering drugs or medications such as insulin |

How Does Our Health-Care System Create Fertile Soil for FIIC?

Modern medical systems are increasingly specialised and fragmented. The Australian system relies on a large private sector and, within the cities in particular, paediatrics is increasingly specialised and therefore siloed. Diagnosis-orientated funding models encourage solution-focused, direct-action approaches. The electronic medical record system encourages ‘copy and paste’ diagnoses and generalised ‘smart sets’ for testing. No central health record is maintained that is accessible to health-care providers. Such systems may inadvertently create barriers that impede consideration of FIIC.4 Parents can easily seek multiple specialists' opinions, ‘sack’ doctors they disagree with, and enlist other professionals to their cause.

‘Red Flags’ for FIIC

FIIC needs to be CONSIDERED before it can be RECOGNISED and should always be included in the differential diagnosis of medically unexplained or perplexing presentations or when the child's presentation does not make sense (see Table 3).

| Red flags for recognition | |

|---|---|

| The child's condition | Reported symptoms and signs are not independently observed |

| Reported symptoms and signs are not fully explained by the child's diagnosis | |

| Reported signs and symptoms are bizarre, for example, multiple allergies to environmental substances | |

| Reported symptoms and signs are not explained by test results (multiple normal results, especially for tests infrequently ordered) | |

| Inexplicable poor response to standard treatments | |

| Symptoms disappear or improve when carer is absent | |

| Unexplained impairment of child's daily life | |

| Things just do not seem to make sense… it just does not add up… | |

| The care giver's behaviour | Mother is the sole source of information – refuses to allow child to be seen alone, talks for child, viewed as strong and caring advocate, elicits public sympathy, father absent |

| Repeated reporting of new symptoms that may be curious and intellectually challenging | |

| Insists/demands more tests, referrals, opinions, treatments but without improvement; cannot be reassured or follow recommendations | |

| Insists on referral to ‘top’ experts | |

| Denies and argues against normality – does not want child to be well, needs 2nd opinion, resists positive change to health, pleased with bad news, negative about good news ‘you must have got it wrong’ | |

| Flatters doctors who comply but angry, threatening and disengages if challenged. May become litigious or threaten to report doctor to AHPRA | |

| Repeated attendance at medical settings, doctor shopping (can be in combination with FTA/cancellations) | |

| Objection to communication between professionals. Refuses permission to share information about child with previous or concurrently treating doctors | |

| Denigrates or makes frequent unflattering remarks or complaints about other health-care professionals |

How Can Paediatricians Respond to Concerns About FIIC?

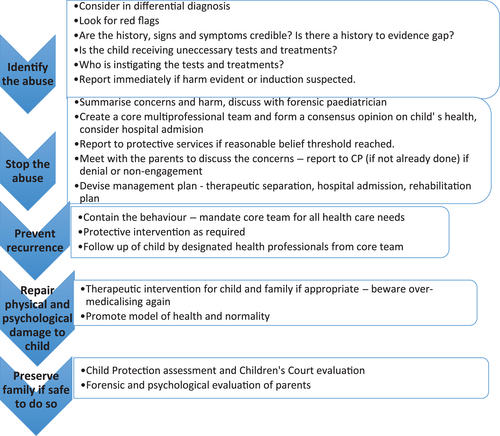

- Are the history, signs and symptoms of disease credible? What is the actual state of health of the child? Is there a ‘history to evidence gap’?

- Is the child therefore receiving unnecessary and harmful or potentially harmful medical care?

- If so, is the care being instigated primarily by the care giver or by a health-care provider?

Once concerns have been identified, STOP and ACT to protect. At this point, no further tests or treatments on the basis of maternal requests in the absence of objective evidence of a child's need for treatment should be ordered. If induction of illness and imminent risk to the child is suspected, act immediately by reporting to protective services and retaining any potential evidence.

If imminent risk to the child's life is not thought to be present, a useful first step is for the treating paediatrician to carefully collate the child's current health information, establish the child's current state of health and summarise the identified concerns. Identifying a multiprofessional, multiagency team is a crucial part of the management of FIIC. The team may consist of medical professionals (general paediatrician (GP), paediatric specialists, a forensic paediatrician, the family GP), school staff, psychiatric services, social work, allied health, senior nursing staff, protective services and sometimes Police. The team approach allows a consensus formulation about the child's current state of health to be reached, allows sharing of concerns, facilitates planning of a coordinated approach and helps guard against splitting of professionals.

An admission to hospital may allow an opportunity to observe the child's behaviour and monitor their medical condition in the absence of their carer – a ‘therapeutic separation’. Arranging a nurse special to observe parent–child interaction can be invaluable and objective but detailed documentation is imperative. This may be a chance to interview the child or other family members alone.

Following a multi-professionals meeting, or perhaps during the course of a planned admission, the lead paediatrician is advised to meet with BOTH parents in the presence of a social worker or other professional in order to communicate the concerns, hear their explanation, and inform them of the need for the behaviour to cease in order to prevent further harm to the child. A transparent and honest approach is suggested that aims to be supportive, address anxiety and present an ‘as of now’ view. A rehabilitation plan should be agreed, that includes explaining the concerns to the child if developmentally appropriate. The response of both parents to this meeting can be an important diagnostic feature and should be carefully documented. See Figure 3 for a suggested approach to management.

When Should a Report to Protective Services be Made and What Is the Role of the Forensic Paediatrician?

If a professional forms a reasonable belief that FIIC is present, then a report to protective services should be made. It is important to understand that carer behaviour can escalate once the care giver has been confronted with allegations regarding FIIC. A report to protective services is mandatory once evidence of fabrication or induction is established, if there is clear evidence of harm to the child, if there is disagreement with the consensus feedback or if there is non-compliance with the agreed rehabilitation plan. In cases where the parents reach an understanding and agree to a rehabilitation plan a report may not be immediately necessary but close follow-up is advised.

Even in cases where harm is established, convincing statutory authorities that separation may be necessary can be extremely difficult, especially when the child, siblings and family rally together to deny the possibility of abuse. In such cases, a more detailed evaluation is often necessary and requesting the assistance of a forensic paediatrician can be valuable. This needs explicit consent from the parents or the Courts. Protective services can provide information about previous concerns and family functioning in the community and are able to access the entirety of the child's (as well as the sibling's and mother's if required) medical histories including all private medical and allied health providers as well as Medicare statements, Centrelink information, NDIS records, social media accounts and school reports. This information can be provided to the forensic paediatrician who performs a detailed analysis of the complete record (reads every page!) and produces a chronology of the child's medical history looking for evidence of exaggeration or embellishment of signs and symptoms (more severe or more often than is real), fictitious or fabricated signs and symptoms (they are made up), fabricated documents or test results (names or dates altered, false signatures) and/or induction of illness (the child is actively being made unwell). The forensic paediatrician can provide a medicolegal report that tabulates this information, formulates an opinion by analysing and categorising the child's signs and symptoms, and provides clear and comprehensive recommendations for protective services to help ensure the ongoing health and safety of the child.

What Happens Next?

Once a plan for rehabilitation has been agreed a single treating ‘team’ should be established and all the child's care should be accessed through a limited number of designated professionals. A line of support may need to be established for the GP or school counsellor, for example, so they are able to directly access designated paediatric or mental health practitioners. Long-term follow-up is vital if the child remains in the care of the perpetrator. Psychiatric evaluation of the parents and psychological therapy for the child is recommended. The father may be re-engaged while the mother undergoes further assessment. The prognosis for reunification is poor if the mother fails to develop insight or acknowledge the assertion that she caused harm.

Although challenging, FIIC can be diagnosed and managed by paediatricians working in mainstream paediatric practice. It takes time and effort to gather information and develop a case formulation, but early diagnosis can have significant positive benefits in changing the life trajectory of the children affected by this condition.