Staff structural empowerment—Observations of first-line managers and interviews with managers and staff

Funding information: The Swedish Society of Nursing; University of Gävle

Abstract

Aim

The aim was to study how first-line managers act to make structural empowerment accessible for nursing staff and furthermore to relate these observations to the manager's and their nursing staff's descriptions regarding the staff's access to empowering structures.

Background

Staff access to empowering structures has been linked to positive workplace outcomes. Managers play an important role in providing the conditions for structural empowerment.

Method

Five first-line managers were observed for two workdays. Managers and staff (n = 13) were thereafter interviewed. Field notes and interviews were analysed using directed content analysis.

Results

The managers displayed intentional actions that could enable their staff access to empowering structures. Managers and staff described the importance of staff's access to empowering structures.

Conclusion

Staff who perceive to have access to structural empowerment have managers who are present and available. Unanimity among managers and staff existed in regard to the importance of staff having access to structural empowerment. The managers work continually and intentionally, doing many things at the same time, to provide the staff access to empowering structures.

Implications for Nursing Management

The study shows the importance of promoting managers' awareness of staff's access to structural empowerment and maximizing managers' presence and availability to their staff.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ongoing organisational changes, nursing shortages and problems retaining nurses are global challenges for managers (World Health Organization, 2020). To meet these and other health care challenges, good access to empowering structures such as those described in Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993), access to recourses, information, opportunities support and formal and informal power, has been emphasized as being central to nurses' well-being and effectiveness. First-line managers (FLMs) play a central role in providing access to these structures. Studies have shown links between the nursing staff's perceived access to empowering structures in the workplace and positive outcomes for both staff (Cicolini et al., 2014; Engström et al., 2011) and patients (Engström et al., 2021). FLMs should provide their staff access to empowering structures. However, it has been found that FLMs struggle on a daily basis to provide the staff with the sufficient prerequisites necessary to perform their work (Ericsson & Augustinsson, 2015; Labrague et al., 2018). Leadership style/how they act is also known to influence several positive nursing staff-outcomes (Boamah et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018). The present study focuses on how FLMs actually act in their everyday work to give their staff (hence used for nursing staff) access to empowering structures and what descriptions they and their staff give regarding the staff's access to structural empowerment.

1.1 Theoretical framework

In Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993) of structural empowerment, the role of management is to provide employees with necessary structures that support, empower and strengthen their ability to perform their work in a meaningful way. An individual's behaviour and attitudes towards work, according to the theory, are influenced by the individual's access to structural empowerment rather than their personality or abilities. These structures are access to resources (materials, supplies, personnel and time), information (updated and relevant for work and organisation), opportunities (to learn and develop new knowledge, skills and career) and support (encouragement, feedback and help from superiors, colleagues and subordinates). Employees with access to these structures are empowered (Wong & Laschinger, 2013). Access to these structures is influenced by formal power (a visible work role that includes mandate[s]) and informal power (a network of alliances within and outside the workplace). Kanter (1993, p. 166) describes power as “the ability to get things done, to mobilize resources, to get and use whatever it is that a person needs for the goals he or she is attempting to meet.”

1.2 Overview of the literature

Kanter's (1993) theory of structural empowerment has been used in nursing research in different contexts and countries and from both the combined and separate views of FLMs and staff. It has been found that when FLMs' ratings of their access to structural empowerment change over time, so do their subordinates' ratings (Hagerman et al., 2017). Furthermore, the FLMs' access to structural empowerment were positively related to their staff's ratings of their FLM's leadership and management (Hagerman et al., 2017).

Studies using Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993) have shown positive relationships between staff-rated access to structural empowerment and job satisfaction (Cicolini et al., 2014; Engström et al., 2011), well-being (Engström et al., 2011; Spence Laschinger et al., 2011) and organisational commitment (Yang et al., 2014). Furthermore, that empowering workplaces retain nurses and prevent burnout (Meng et al., 2015). Additionally, positive relationships were found between staffs' access to structural empowerment and patient satisfaction (Engström et al., 2021), staff-rated quality of care (Engström et al., 2011), professional nursing practice behaviours (Manojlovich, 2010) and evidence-based practice (Engström et al., 2015).

In an interview study, formal power was described facilitating access to empowering structures and enabling preventive work for district nurses (Eriksson & Engstrom, 2015). Another interview study that used Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993) deductively found that internationally educated nurses described informal power acquired by networking with people both within and outside the organisation as being especially helpful (Eriksson & Engström, 2018). Skytt et al. (2015) found that FLMs expressed an awareness of the importance of their subordinates' access to empowering structures. Further they described how they in their roles as FLMs could contribute to make these structures accessible.

To sum, there are a number of quantitative studies supporting links between empowering structures and staff well-being (e.g., Engström et al., 2011; Spence Laschinger et al., 2011) and some related to care quality (e.g., Engström et al., 2011, 2021). There are a few interview studies supporting Kanter's theory of structural empowerment (e.g., Eriksson & Engström, 2015, 2018; Skytt et al., 2015). There is also research linking FLMs' structural empowerment (Hagerman et al., 2017) and leadership styles to staff structural empowerment (Boamah et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018). However, less is known about how FLMs actually act, what they do and how they do it, to provide staff access to empowering structures. No observational studies with the perspective of structural empowerment have been found. Observations as a data collecting method is well suited for capturing specific social phenomena (Knoblauch, 2005), as the work of FLMs and interactions between them and their staff (Arman et al., 2009; Mintzberg, 1994).

1.3 Aim

The aim was to study how first-line managers act to make structural empowerment accessible for nursing staff and furthermore to relate these observations to the manager's and their nursing staff's descriptions regarding the staff's access to empowering structures.

2 METHOD

2.1 Design

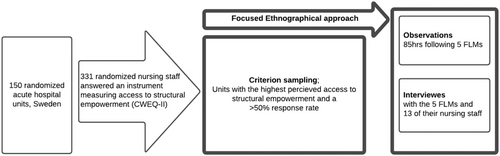

The study had a qualitative descriptive design (Figure 1) that used a focused ethnographical approach (Knoblauch, 2005), collecting data with observations and interviews. This approach provides insights into a topic-oriented focus on actions, interactions and social situations (Knoblauch, 2005) where the topic in the present study is staff's access to structural empowerment. In accordance with Jerolmack and Khan (2017) and Wilson and Chadda (2009), the theory of structural empowerment (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, 2010) was therefore used as a standpoint for the inclusion of units, data collection and data analysis. For a purposeful selection of cases, the FLMs (informants) were selected from another study (Lundin et al., 2021) focusing FLMs' and staff's working situation in Swedish acute hospitals. In that study, a randomized sample of nursing staff had answered a survey including the Condition of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II), measuring structural empowerment (Laschinger et al., 2001). A criterion sampling was made for the present study.

2.2 Sample and settings

Initially, five FLMs at units with the highest ratings of staff's access to structural empowerment and a response rate of >50% were contacted by the first author, using telephone and email. Information was given about the study aim. Three FLMs declined due to reorganisations; one unit was being shut down, and two were leaving their positions. An additional three FLMs from units fulfilling the criteria were approached and agreed to participate. The final sample consisted of five FLMs and 13 staff members. The staff consisted of registered nurses (including one assistant manager) and nurse assistants. The participating staff had been on duty on at least one of the days their FLM was observed. For setting and sample characteristics, see Table 1.

| Number | Age, range/median | Gender | Years as FLM range/median | Years at the unit, range/median | Units with posts as assistant managersa | Number of employees, range/median | Hours staffed | Number of organisational sites per FLM, range/median | Hospitals Public/private | Unit specialty Medical = M Surgical = S Dialysis = D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h/7 | 07–22 | ||||||||||||

| Units | 5 | 4 | 27–42/35 | 2 | 3 | 1–4/2 | 4/1 | M = 1, S = 1, D = 3 | |||||

| FLMs | 5 | 31–56/47 | ♀ 4 | ♂ 1 | 1–11/5 | 1–11/5 | |||||||

| Registered nursesb,c | 9 | 23–59/43,5 | ♀ 8 | ♂ 1 | 1–27/3,5 | ||||||||

| Nurse assistantsc | 4 | 47–57/54,5 | ♀ 4 | 1–28/25 | |||||||||

- a At the time of the observations, there were two assistant managers on sick leave, one worked part-time and was not present, and one position was vacant.

- b Including one assistant manager.

- c In the text referred to as staff or staff members.

2.3 Data collection

Data were collected through participant observations and interviews (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007). The FLMs suggested three continuous days for data collection at their unit. First, FLMs were observed during workdays. After the observations, interviews were conducted with the FLMs and staff in a secluded room of the participant's choice at the units, during working hours. Data were collected over a 4-month period starting in the fall of 2017 by the first author (RN, lecturer, PhD student) and the last author (RN, Senior Lecturer, PhD), both females with previous experience of working in acute hospital settings and performing qualitative research.

2.3.1 Observations

The observations totalled 85 h, included two full working days for four FLMs and 1 day for one FLM. Written field notes of the FLMs' activities were made and resulted in 100 pages of transcribed field notes. In the beginning, at all five units, the researchers observed simultaneously, and after an hour, the notes were compared to confirm similar things had been noted. Then the researchers took turns observing, which enabled them to be focused. At some units, the staff had been previously informed of the observations, and at others, the observers were introduced on the observation day. The observers remained in the background wearing private clothing and a name tag identifying them as coming from a university. In most of the activities observed, the FLMs interacted with other persons (staff, colleagues, etc.). Observations were paused in situations involving patients or delicate staff matters. When the researchers did not understand what the FLMs were occupied with, clarifying questions were asked during the observation. During and after each observed working day, the researchers had reflexive discussions about what they had observed. These discussions led to questions being added to the interview guide (Table 2).

| Interview questions | Theoretical framework |

|---|---|

| … units that we looked at in Sweden, have made ratings … // … and here [pointing to the results] is the average from those that answered the survey … // … here with you, you are among those that have ratings at the higher end … on all this compared to most others, what do you think is the reason for this at your unit? | Opening question |

|

How would you describe the availability of resources such as personnel, time and materials that are needed to accomplish the work here at the unit? If there is a shortage of personnel for a shift, what do you do? |

Resources |

|

We have attended some meetings that you have had at your unit and would like to know a little more about what sort of meetings you usually have and what is brought up on those occasions? How do you get access to the information you need to do your work? |

Information |

| As a nurse, what possibilities for career development are there here? | Opportunities |

| The support you describe that you have, where does it come from and how is it manifested? | Support |

| We have observed that you nurses have different roles, could you please clarify what roles exist here, what they include and what significance they have for the unit? | Formal power |

| These networks that you nurses describe you have, what significance do they have in your work? | Informal power |

| Examples of questions origin from the observers' reflexive discussions |

|---|

| I have thought of another thing, and the other observer has also said that, you do everything at once (act on a problem or question without delay). Have you thought about that? |

| We have been a little curious about, uh, this division between the FLM and the assistant manager. We have not seen the assistant manager during these days, so we have not got a clear picture of how it is laid out. Can you tell a little about that from your point of view? |

| Because I also thought the other day, then it was something (a question of resources/staffing), and then you just left that information in both places (to both sections/staff groups) and then you and I sat here and within two, three minutes, two people (from each section/staff group) came (offering their services) and then the problem was solved, that's how it works? |

2.3.2 Interviews

The audio-recorded interviews were semi-structured. Questions concerning what the researchers had observed and questions based on Kanter's theory of empowerment were asked with the aim to get descriptions and reflections on the staff's access to empowering structures (Table 2). The last author interviewed the FLMs (n = 5; range 62–167 min), and the first author the staff (n = 13, two via telephone; range 17–43 min). The FLM interviews differed in time from staff interviews as questions more often where addressed to the FLMs to get a deeper understanding of what had been observed. The researchers listened to the audio recordings the same day or the day after the interviews. All participants had agreed on being contacted for further questions and clarifications if needed, although that was never needed.

2.4 Data analysis

A directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) based on Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, 2010) was performed. Field notes and transcribed interviews were read through several times. Meaning units relating to the aim were identified, and when needed, condensed before being labelled with a code. Thereafter, the codes were deductively sorted into categories based on Kanter's theory of structural empowerment as described by Kanter (1993) and Laschinger (2010). For examples of the data analysis see Table 3. The first author conducted the analysis and discussed the categorization together with all four authors until a consensus was reached.

| Meaning units from field notes and interviews | Code | Category |

|---|---|---|

|

Time for a staff meeting. FLM says, “Let us assemble the troops” and goes into nurses' station. FLM gets the phone. It is a conversation about a patient who needs a private room and is to be admitted right away. Discusses this and who should take care of the patient. Speaks with a new staff member about his start and introduction at the unit. FLM says “We can talk more tomorrow about how you want to do it.” New staff member, “I'll go between.” Gives a report to the nurse who will receive the patient who is coming and explains the reasons for the solution reached. Goes to the staff room for the meeting. (Observation FLM 1) |

On the way to the staff meeting, he/she gets the staff to assemble, receives a phone call regarding a patient, discusses and plans for the patient along with informing the staff member, and then with the new staff member discusses the issue of the introduction before returning to the meeting that will start. | Information |

|

7:30 the meeting ends, FLM speaks further with a staff member about how best to plan the day's work, FLM listens to the staff member's proposal and asks if it is possible for them to speak to the nurse in unit X, makes plans to work one staff member short in the evening. FLM summarizes where the focus should be, encourages staff members to read in the patient records. (Observation FLM 2) |

Has conversations with staff members about how to plan for the day's work and staffing. |

Resources |

|

FLM asks, “Otherwise how's it going?” [referring to introduction] Nurse says, “It's going well, a bit turbulent today, but everyone is super cool.” FLM tells him that they will have a follow-up meeting on this and gives him tips on who he can share his thoughts with. (Observation FLM 3) |

FLM asks how it is going for the new staff member during the introduction, informs that there will be a follow-up meeting to discuss the introduction, and suggests another staff member as a source of support. |

Support |

|

“You get the feeling that our managers trust us and give us a lot of responsibility, and then you grow all the time with that responsibility. And I think it's really enjoyable of course, and so you want to have more and more responsibility and do more things. I think it will be a pretty dedicated staff.” (Interview staff 1.1) |

The managers trust us, give us responsibility and then a person wants more responsibility, it becomes a dedicated staff. |

Opportunities |

| “Yes … as a coordinator you have quite a lot, you are like “the air traffic controller” that should keep track of everything. And then has a mandate to decide where patients will be placed and who should be redirected.” (Interview staff 3.2) | The coordinator is “the air traffic controller,” keeping track of everything and has the mandate to decide about the placement and redirection of patients. | Formal power |

|

“I have worked a long time at the hospital and have contacts everywhere and know who to contact, which of course I make use of.” (Interview staff 1.2) |

I have contacts everywhere in the hospital and I make use of them. |

Informal power |

2.5 Ethical considerations

The Regional Ethical Review Board (reg. no. 2016/107), approved the study. All participants received oral and written study information, and about voluntary participation.

3 FINDINGS

What was seen during the observations was often confirmed and/or given a deeper understanding in the interviews. The descriptions about access to the empowering structures did not show any specific pattern related to the different staff groups, and the result text thereby represents both staff groups. The findings are presented under the deductive categories from Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, 2010) followed by a description of what characterized the FLMs' activities during the working day. Illustrative texts (identified with participant number) from field notes and interview quotations are presented to support the descriptions.

3.1 Resources

A staff member comes in inquiring if the FLM had gotten enough staff for the evening and offers to stay. FLM is “very grateful”. The staff member wonders at the same time about a change she wishes regarding a day off. FLM checks the schedule and says it looks OK if FLM can move someone from the evening to the day shift. FLM will ask the relevant staff. (Observation FLM 4)

Due to special competency needs, the dialysis units had to manage staffing, while the others had access to a personnel pool. The dialysis units did have the possibility to reschedule patients. The person rearranging the schedule and arranging additional staff differed, but at every unit, it was clear who had the responsibility and their mandate.

We could see and hear that staffs were very much involved with the equipment and supplies, in both planning and executing preventive maintenance strategies and evaluating and deciding on new equipment and materials. FLMs always welcomed staff's proposals, but they explained they did not always have the possibility to accommodate the staff's wishes. Depending on their preference or work needs, the FLMs dressed in private or nursing clothing. At times, the FLMs were seen taking inventory and unpacking supplies, helping with patient care and joining unit social activities. They described how important it was to take part in such activities when staffing was strained.

During the observations and interviews at the inpatient units, it became clear that their resources were often affected by other units' lack of resources. Consequently, we noticed that their planning would be upset by unpredicted admissions from other specialized units. We overheard discussions between the FLMs and staff over patient safety. The staff voiced a feeling of insecurity and uncertainty with the patient care and disappointment over administrative agreements that were not followed. The FLMs reacted strongly, for example, immediately approaching their manager and the involved departments' management as well as giving information and feedback to their staff.

3.2 Information

Yes, I sift away quite a bit. Because it should be what interests and benefits the unit. And gives energy or that takes energy too. But otherwise, I do not bring it up. (Interview FLM 2)

As far as I'm concerned, it works well that way, we do not get too much information, because I feel that I could not handle it. (Interview staff 2.1)

FLMs and staff described the importance of communicating strategies and goals concerning patient care. That was perceived as important in their daily work and for reaching national goals within their specialty. Both aspects were described as important for recruiting and retaining competent colleagues. The FLMs were seen giving the same information via different channels like bulletin boards, emails and verbally. Coffee and lunch breaks were used for socialization as well as for spreading and gathering information. Some FLMs described how they used as many information channels as possible to ensure that all staff members, both regular and extra, had timely access to new information and also prevent rumours and uncertainty. Others, when asked, had not reflected over that as a strategy. FLMs and staff described verbal information to be the most effective and preferable. When staff requested information from the FLMs, either in person, via telephone or email, most often they received an answer quickly even if the FLMs had to search for the information.

3.3 Support

When following the FLMs, we saw how they were observant of people they met, often sharing a word or two, and giving recognition to staff in many different situations. During the interviews, they expressed the importance of having good and supportive relationships with the staff, which gave the foundation for constructive support. Staff perceived having support from their FLMs, but they also stressed the importance of giving each other support as a way to retain colleagues and handle periods of heavy workload.

As a support, the FLMs were seen encouraging staff to find their own solutions or information to solve problems, and later checking to make sure it went well. During the interviews, the FLMs reflected on how they perhaps too often gave assistance instead of directions or suggestions on how to solve the problems.

… Yes, you feel she is with us. I think there is so much more FLMs run around to nowadays. There are meetings here and there, and FLMs aren't around, and they are hard to get a hold of, but our FLM manages to be here for us. (Interview staff 5.3)

We observed many examples of how the staff came by the FLMs office with practical work-related issues and matters of a more private personal character. The FLMs quickly closed the door and sat down together with the staff member for as long as needed. Afterwards, the FLMs made sure the door was opened again to signal availability.

3.4 Opportunities

And I can easily get bored if I'm just doing my job, if it is only nursing, nursing, nursing. It's nice if you can do something new. Develop … It was really great when they came up with that idea [task shifting]. It made it, so that I feel like I can stay here a bit longer. (Interview staff 1.3)

It was important to the FLMs that the staff felt comfortable in their roles before taking on an expanded role or participating in special task groups. This strategy was not understood by everyone and could therefore, at times, be experienced as a lack of trust from the FLM.

… It's one thing to say that you are going to be involved, and have influence and develop your work and your unit. But if there's never any time set aside, then you cannot. And here it actually happens. (Interview staff 1.1)

3.5 Formal and informal power

Several different work roles giving considerable responsibilities to staff were observed and described. Coordinators are examples of work roles with formal power. The staff had the mandate to place and rearrange patients, signal to the FLM if extra resources were needed and then allocate such resources. At one unit they assigned a staff member to every shift outside of office hours who was in charge of calling in staff when needed. Dialysis staff described having a very central role in planning and deciding patient care, and their knowledge was highly recognized and respected by others in the organisation.

For issues involving practical questions, it's often us nurses who encounter them. And our contact network extends throughout the country. (Interview staff 5.2)

3.6 Interweaving structures

The different structures from Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993) are described above one by one, but during the observations, they were often seen to be interwoven. The FLMs' activities had a varied content and time frame. At all units, the FLMs were seen working and handling different tasks as well as current and planned issues affecting the daily operations at the unit simultaneously; often on the go and in dialogue with their staff. For example, we observed that on the way to give information, the FLM stopped and discussed the need for extra staffing and then continued to give the intended information. Their workdays seemed seamless and activities, if not overlapping, followed directly one after another; often including several of the described categories. Day to day management and leadership activities ranged from a few minutes to meetings lasting more than an hour.

4 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to observe how FLMs in hospitals act to support their staff's access to structural empowerment. The results show how the FLMs intentionally worked to enable staff access to empowering structures; often with activities and strategies overlapping each other. An unanimity between the FLMs and the staff members emerged from their descriptions regarding the importance of staffs' access to these structures in line with Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, 2010).

The FLMs allocated much of their time appropriating sufficient resources (cf. Ericsson & Augustinsson, 2015), and staff-rated access to resources has been shown linked to job satisfaction (Engström et al., 2011). The FLMs strategically chose to delegate tasks to their assistant managers or staff with other formal roles. This was done to facilitate a smooth running of the daily activities and during days of high stress. FLMs dressed in work clothes to signal themselves as a resource for the staff. Taking an active part in patient care has been described as not being an FLM role (Ericsson & Augustinsson, 2015; Skytt et al., 2008), but other studies show how it is still a part of what they do (cf. Duffield et al., 2019). In our study, it was seen as standard policy and appreciated by the staff.

The importance of the staff having access to information was described by the FLMs, which led to many activities (cf. Arman et al., 2009). The staff described their trust in the FLM to secure all the important information they needed (cf. Skytt et al., 2008, 2015). In the present, and in Hagerman et al. (2015), new information given in a timely manner was described as important for preventing rumours and causing uncertainty. Further, inadequate and unclear information has been described as a source of frustration (Ericsson & Augustinsson, 2015; Hagerman et al., 2015).

Staff and FLMs described a shared view regarding the importance of the staff's access to opportunities and the FLMs tried to enable their staff's participation in activities that the individual and the organisation could gain from (cf. Engström et al., 2011). At the dialysis units this strategy had “paid off,” and both FLMs and staff expressed how the staff acquired valuable special knowledge that gave them access to formal power (cf. Kanter, 1993).

The FLMs described the importance of having a good relationship with the staff, and being present and available at the unit, which was an important foundation for giving staff direct support and feedback (cf. Skytt et al., 2015). FLMs expressed a hope that a supportive relationship, based on presence and feedback between them and the staff, would lead to supportive relationships within the staff group ensuring a supportive climate when needed. Supportive climates and empowering structures have also been described to be of great importance in previous studies (Eriksson & Engström, 2018; Yang et al., 2014). The staff in the present study described the support they give to one another to be of great importance especially in times of high stress.

How these FLMs prioritize their availability to their staff, and intentionally act to promote their staff's access to empowering structures are in line with Kanter's theory (Kanter, 1993), and can be seen as good examples. Our findings can be considered an important contribution to research concerning staff structural empowerment and the role of management for two reasons. The findings were derived from data collected from both observations and interviews, and from a sample of units with the highest ratings of staff's access to structural empowerment.

Despite changes in the FLMs' responsibilities and the health care system over the past years (Rosengren & Ottosson, 2008; Thorpe & Loo, 2003; Willmot, 1998), our findings show how the content and activities characterizing FLMs' workdays are still similar to earlier descriptions (Arman et al., 2009; Mintzberg, 1994). However, in contrast to previous studies where FLMs did not always reflect on and discuss strategies to make empowering structures accessible to their staff (Hagerman et al., 2019; Skytt et al., 2015), the FLMs in our study did express an awareness of these structures and had strategies for making them available to their staff. The FLMs' actions and reflections in our study have resemblances to transformational leadership style (Bass & Riggio, 2006), which has been positively associated with nurse-rated access to structural empowerment (Boamah et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018).

4.1 Methodological reflections

A strength of this study was that the findings from the observations could be confirmed with interviews. To ensure dependability, the first and last author conducted all observations and interviews. Being aware of the potential weakness of being two observers, the observers often checked in with each other on what had been observed and compared field notes, in some way, calibrating themselves as observers. The advantages of being two observers is that it enabled keeping a focused mind during the observations and capturing a more complete picture of the FLMs working days. Together they reflected on what had been observed and which questions to add to the interviews next day in the search for a deepened understanding. The main interview questions were used as a checklist for covering the same topics. Both FLMs and staff considered the days, where the observations occurred, as representative for the FLMs actions as well as for the activities at the unit. Data were collected over a limited time period, followed by the transcription of field notes and interviews to strengthen dependability. Members in the research group had various experiences from hospital settings, managerial positions and previous experience with observations, interviews and content analysis. The open and reflexive dialogue concerning the findings until a consensus was reached by all authors strengthened credibility. Through the detailed sample and procedure descriptions, the reader can decide whether the results can be transferred to another context or group.

5 CONCLUSION

Staff at hospital units who perceive to have access to structural empowerment have FLMs who are present and available. Unanimity among FLMs and staff existed in regard to the importance of staff having access to structural empowerment. That the FLMs worked both continually and intentionally doing many things at the same time to provide the staff access to empowering structures contribute to the understanding of managers role in Kanter's theory.

5.1 Implications for nursing management

FLMs can be inspired by our results showing good examples of managers recognizing and demonstrating the importance of giving staff access to empowering structures. FLMs should be given support to maximize their presence and availability to their staff. This can be achieved, for example, by developing the assistant manager's role to one that is supportive to both FLMs and staff and placing the FLM's office in close proximity to the staff.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all the participants in the study and especially the FLMs for their willingness to be observed and thereby provide rich and valuable data.

The project was supported by the University of Gävle and The Swedish Society of Nursing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board of Uppsala (Dnr 2016/107).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.