Implementing person-centred key performance indicators to strengthen leadership in community nursing: A feasibility study

Abstract

Aims

To explore the utility and feasibility of implementing eight person-centred nursing key performance indicators in supporting community nurses to lead the development of person-centred practice.

Background

Policy advocates person-centred health care, but few quality indicators exist that explicitly focus on evaluating person-centred practice in community nursing. Current quality measurement frameworks in the community focus on incidences of poor or missed opportunities for care, with few mechanisms to measure how clients perceive the care they receive.

Methods

An evaluation approach derived from work of the Medical Research Council was used, and the study was underpinned by the Person-centred Practice Framework. Participatory methods were used, consistent with person-centred research.

Results

Data were thematically analysed, revealing five themes: giving voice to experience; talking the language of person-centredness; leading for cultural change; proud to be a nurse; and facilitating engagement.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that implementing the eight person-centred nursing key performance indicators (KPIs) and the measurement framework is feasible and offers a means of evidencing person-centredness in community nursing.

Implications for Nursing Management

Person-centred KPI data, used alongside existing quality indicators, will enable nurse managers to evidence a high standard of care delivery and assist in the development of person-centred practice.

1 BACKGROUND

In a move to broaden perspectives of quality in global health policy, there is an increased focus on humanizing health care, foregrounding patient and carer experiences (Picker Institute Europe, 2014; World Health Organisation (WHO) 2016; Department of Health, 2016). This has positioned person-centredness alongside safety and efficiency in many national and international policies and recognizes person-centred care as a core competency in the health care workforce (Nursing & Midwifery Council, 2018; WHO, 2005). Evidencing quality care in community nursing services has become a leadership imperative; however, it is little explored (Maybin, Charles, & Honeyman, 2016).

In the UK, current quality measurement frameworks in the community focus on incidences of poor or missed opportunities for care (e.g. falls, pressure ulcers, infection rates), generated through national data sets, perhaps accounting for the invisibility of community nursing reported in the literature (Maybin et al., 2016; Queens Nursing Institute, 2017). This narrow view of quality standardizes practice across health care organisations and disciplines, often without incorporating individual experience of care (Foot et al., 2014; Horrocks et al., 2015; Kaehne, 2018). Rather than capturing person-centredness, quality indicators serve to create a negative view of evaluation within community nursing. To add to this, less robust reporting mechanisms in the community, when compared to hospital settings (Foot et al., 2014), mean data are not locally owned or used to improve care experiences for service users, consistent with new service models.

Community nursing does not always lend itself to clear-cut short-term clinical outcomes in the same way as a defined episode of care for an acute illness, and consequently, Horrocks et al. (2015) proffer indicators cannot be used ‘off the shelf’. Care is often long term, aimed at prevention or promotion of health and well-being. New models of care rely on strengths-based approaches, tapping into and promoting social capital. Models such as the ‘House of Care’ (Coulter, Roberts, & Dixon, 2013) encompass person-centred thinking, purposefully moving away from traditional ways of working, often viewed as reactive, fragmented models of care. However, more proactive, holistic and inclusive perspectives of care are difficult to measure. Finding ways to evaluate person-centred practice in the community must therefore be prioritized.

An alternative set of eight nursing key performance indicators (KPIs) was developed by McCance, Telford, Wilson, MacLeod, and Dowd (2012) that were sensitive to the unique contribution of nursing and focused on improving patient's experience of care. The eight KPIs, which are presented in Table 1, are considered novel in the context of the existing evidence base and are different from the other quality indicators generally used. The eight KPIs were also person-centred in their orientation as evidenced by their alignment to the Person-centred Nursing Framework (McCormack & McCance, 2019). A set of measurement tools was also developed to accompany the KPIs, and comprised 4 data collection methods, including the following: a patient survey; an observational tool; patient and family stories; and a review of the patient record undertaken in conjunction with nurse interviews (McCance, Hastings, & Dowler, 2015) (Table 2).

|

KPI 1: Consistent delivery of nursing care against identified need KPI 2: Patient's confidence in the knowledge and skills of the nurse KPI 3: Patient's sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse KPI 4: Patient involvement in decisions made about his/her nursing care KPI 5: Time spent by nurses with the patient KPI 6: Respect from the nurse for patient's preference and choice KPI 7: Nurse's support for patients to care for themselves where appropriate KPI 8: Nurse's understanding of what is important to the patient and their family |

- Abbreviation: KPI, key performance indicator.

| Measurement tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Patient survey | The purpose is to capture quantitative data via a questionnaire comprising 8 Likert-type questions relating to each of the KPIs |

| Patient stories | The purpose is to understand the patient's care experience and to capture, through their story, what is important to them and what would improve their experience. Stories are reviewed through the lens of the KPIs to identify evidence related to any of the 8 KPIs |

| Observing practice | The purpose is to capture nursing presence in patient areas over a period of 30 min related specifically to KPI 5 (time spent by the nurses with the patient) |

| Reviewing the patient record undertaken in conjunction with staff interviews | The purpose is to ask staff questions relating to KPI 1 (consistent delivery of nursing care against identified need) and KPI 8 (nurse's understanding of what is important to the patient) and then cross-check by reviewing the patient record, to establish if there is consistency |

- Abbreviation: KPI, key performance indicator.

The eight KPIs and measurement tools have been tested through a series of implementation studies in a range of different clinical settings across UK, Europe and Australia, including the following: (a) general, specialist wards and mental health inpatients, ambulatory care and a midwifery unit in acute hospital settings (McCance et al., 2015); and (b) paediatric wards within specialist children's hospitals and paediatric wards in general acute care hospitals (McCance & Wilson, 2015, 2016). Findings from these studies confirmed that using the eight KPIs generated evidence that enhanced engagement of nurses to make changes in practice, contributing to an enhanced care experience. The evolution of this research led to a further study to develop and test the feasibility of a technological solution to facilitate the collection of data using the measurement tools. It demonstrated that the App made information more accessible, was captured in real time and used to improve the experience of care (McCance et al., 2020). The person-centred nursing KPIs have largely been tested within acute care settings. This paper reports the findings of a feasibility study to test the acceptability and impact of using these KPIs in community nursing settings with a focus on leading person-centred practice.

2 METHODS

- Strengthen collective leadership of community nurses through the implementation of the KPIs.

- Establish how the KPIs can be used to support community nurses in using evidence to inform their practice.

- Establish views of key stakeholders on the appropriateness and relevancy of the evidence generated by the KPIs as a measure of quality of service provision.

- Test the usability and feasibility of the iMPAKT App for data collection in community contexts.

An evaluation approach guided by the Medical Research Council's (2006) complex interventions framework shaped the research methodology with the Person-centred Nursing Framework as the underpinning theoretical framework (McCormack & McCance, 2019).

2.1 Setting and sample

Teams from different community settings were invited to participate from two health care organisations in the UK, using purposive sampling. Clinical partners, who were co-researchers, disseminated study information and were available to discuss the study. A total of seven nursing teams from different community settings were recruited on a voluntary basis comprising three district nursing teams, two health visiting teams and two family nurse partnership teams (Table 3).

| Organisation | Participating teams |

|---|---|

| South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust (SET), NI |

2 district nursing teams 1 family nurse partnership team 1 health visiting team |

| NHS Lothian, Scotland |

1 district nursing team 1 family nurse partnership team 1 health visiting team |

In order to test the KPIs and feasibility of the iMPAKT App, the study was designed to involve the recruitment of patients/clients, partners and carers. Given the potential vulnerability of patient/clients and children within these community settings, there was detailed discussion with the participating teams on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the purposes of this feasibility study. It was agreed that there would be no involvement of families where there were any active child protection issues or patients who were at the end of life.

2.2 Data collection methods

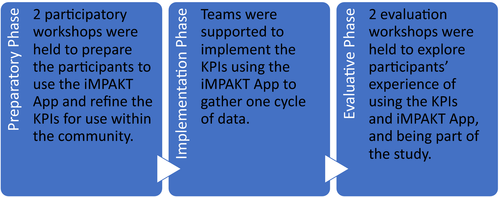

Participatory methods consistent with person-centred research were used, emphasizing that knowledge is not linear and causal but co-created through the relationships we engage in as human beings (McCormack & McCance, 2017). This method was chosen because it promotes a co-operative approach to evaluation, working with people rather than on them, and is based on the premise that the involvement of key stakeholders will develop ownership of the process. Active participation and co-creation were evident in the four phases of the study, which are presented in Figure 1. Data were collected until saturation of common themes was reached.

Feedback from the preparatory workshops led to a revision in two of the measurement tools within the iMPAKT App. The first related to the language within the surveys, which was revised to suit clients being cared for by the different teams; and the second to the observations of practice, which were developed as an activity log, recording time spent in direct client contact, either as a home visit or as telephone contact. Agreement was also reached on the data collection timeline and focus: the timeline for one cycle of data collection would be over a 6-week period where teams would gather a minimum data set of: 20 patient surveys; three patient/family stories (undertaken by the researchers); 10 record reviews; and completion of five activity logs for five members of staff over 5 days. During the second phase of the study, teams decided how and when they would collect data, with support from the research team. During the evaluation workshop, they generated their own action plans following their own analysis of the data. Data generated during each of the collaborative phases and also from the cycle of data collection using the iMPAKT App were included in the analysis.

2.3 Data analysis

Data generated over one cycle comprised a total of 170 surveys, 11 activity logs, 20 record reviews and 11 stories. All the data were uploaded from each clinical setting using the iMPAKT App, and reports related to each of the KPIs were generated and downloaded. An inductive approach was used to analyse the data from the evaluation workshops, aligned to Braun and Clarke's thematic analysis (2006). The study involved a considerable volume of data of high quality, and the data were sufficient to address the research question. Data comprised both the workshop reports and transcriptions from both focus group sessions. Analysis was undertaken within the project team across both sites. Members of the project team reviewed both workshop reports and transcripts individually, then as a group. Following critical discussion, themes were agreed, which are discussed in Results section.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Key ethical considerations for this study focused on: ensuring voluntary participation and gaining informed consent; assuring anonymity and confidentiality for participants where appropriate; dealing with any unforeseen ethical issues such as disclosure of poor or dangerous practice; and protecting those who are vulnerable through, for example, the use of exclusion criteria and development of a distress protocol. The ethical approval process was led by one of the principal investigators in their jurisdiction, and research governance processes were followed to secure governance approval in each clinical site.

3 RESULTS

Some teams experienced difficulty in collecting a full data set during the implementation, which was explored further during the evaluation phase and is considered in Limitations section. Participants revised the measurement framework during the initial preparatory phase, and this contributed to increasing the level of consensus on the appropriateness and relevance of the eight KPIs. Participants' experiences of implementing the person-centred KPIs using the iMPAKT App, the usefulness of the data to develop practice and the overall experience of being involved in the project were articulated through the identification of five themes: giving voice to experience; talking the language of person-centredness, leading for cultural change; proud to be a nurse; and facilitating engagement.

3.1 Giving voice to experience

My nurse is just so kind and nothing you say will shock her; I feel I can be really honest with her. She really helps me make important decisions, because I can be really indecisive at times, so she is amazing at putting all the points out but never convincing me to do anything. (Service user, FNP)

The nurses they always check in with how I am feeling and they know the things that are important to me. They know a lot of things- because we have known each other for a long time they don't have to ask, they can just tell when I have had a bad day. When I have a problem and I can talk to them that's when they really do become a nurse. (Service user, DN)

…it's important to encourage this [way of gathering data} and find out what's important to them [clients], especially since we want to keep people in their own homes, we can really find out what they need and get things put in place. (FG1 DN1)

3.2 Talking the language of person-centredness

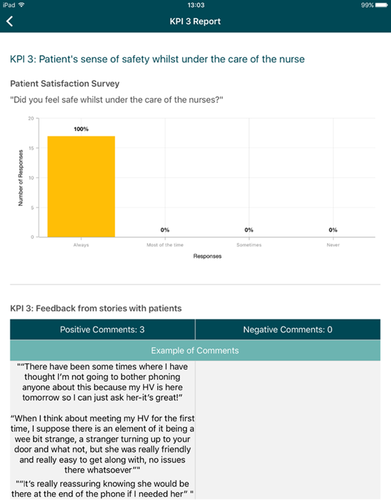

Participants felt data reports acted as a catalyst for open and critical dialogue about practice, enabling teams to have honest and in-depth discussions about person-centred care. There was a sense from participants that reading and reflecting on the stories can really influence practice. Several significant aspects of person-centredness are evidenced in extracts from the stories relating, in particular, to KPI 3: patient's sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse; KPI 4: patient's involvement in decisions made about his/her nursing care; KPI 6: respect from the nurses for patient's preferences and choice; and KPI 8: nurse's understanding of what is important to the patient and their family, as illustrated in Table 4 below.

| KPI evidenced in the story | Extract of story |

|---|---|

| KPI 3: Patient's sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse | ‘A lot of the time they can put me at peace just by what they say to me…they treat me like a friend, but at the back of it they are doing their job’ |

| KPI 4: Patient's involvement in decisions made about his/her nursing care | ‘I remember being really shocked at how much focus there was on me and what I wanted, rather than just asking about the baby. Even my partner got asked how he was and we didn't expect that - it was really nice though’ |

| KPI 6: Respect from the nurses for patient's preferences and choice | ‘My Health Visitor has always just said… Do what is best for you! It doesn't matter what anyone else is doing… And that is such a good thing to hear’ |

| KPI 8: Nurse's understanding of what is important to the patient and their family | ‘While I was pregnant my family nurse she really helped me with my housing and things. She even wrote letters to housing and stuff which was so helpful and supportive’ |

Getting the stories really can influence other practice just though reading- even if it's not directly about you. One of the clients had talked about how valuable she found it that the nurse had paid attention to her partner as well as to her, so just for me to be mindful of how important it is to check in with both of them. (FG1 FNP2)

Potentially this study and the KPIs could be an avenue into that so that they [students] can maybe start to think about person-centredness in their own practices prior to qualifying. (FG1 HV2)

Participants spoke of personal experiences of trying to understand the theory surrounding person-centredness and the difficulty of applying this within everyday practice. The KPIs and emergent evidence provided the basis to have conversations and enabled participants to be intentional about being person-centred and improving service user experiences.

3.3 Leading for cultural change

…having KPIs is sort of like a focus on how the team can lead change and move forward and become more person-centred and understand what the client group want and respond to that, as opposed to ‘this is how we have done things for a long time and this is how we are going to continue’. It's just about changing that structure and leading that. (FG1 HV2)

It is about the quality of the time you do spend with the client and whether the quality of the story and survey match up with the times you say you've spent visiting. (FG1 HV3)

Working with the KPIs allowed teams to take ownership of their practices and enabled them to uncover what improvements might work in their workplace. Co-creating action plans for moving forward within their disciplines demonstrated collective leadership. Some examples are included in Box 1.

Box 1. Action planning

- Take the KPIs away to put up in the office for everyone to see.

- Use this as a philosophy, that is what we are about.

- See the potential in this work, but we understand that we need to build up the team to see the same buy-in.

- Take the findings/report to our next team meeting.

- Try and do some stories ourselves? Monthly? Open questions on paper and get clients to complete?

I would say we could even maybe go out to DNs and help to support them and say ‘listen we have done this and we are also lone workers and we thought it was going to be really hard but look at these benefits’. We could help to support colleagues in different fields and say you know it really isn't that hard or as difficult as you think. (FG2 HV1)

3.4 Proud to be a nurse

As a nurse and as a manager you know seeing that report it actually makes me feel really proud to be a nurse and also for pride of the teams as well you know so we need to acknowledge this and keep the momentum going. (FG2 DN2)

…because we work for such a huge organisation you can sometimes feel really undervalued and that you are just a small part in this big machine but actually this allows us to take ownership of what we are doing and it does empower us. (FG1 HV2)

Even if the feedback wasn't that positive, it still gives you the chance to fix things and discuss with the rest of the team it will also give us the chance to bond and come together with a shared purpose. (FG1 DN1)

3.5 Facilitating engagement

At the start it was quite scary but with practice and the right support it has been very good and as you say it's been like a journey and one which I would be happy to repeat. (FG2 FNP2)

- Surveys and stories were considered appropriate and useable.

- Record review questions were considered more appropriate for recording nurses' knowledge of what was important to service users, but less so for consistent delivery of care against identified need.

- The activity log was considered very insightful, but would be enhanced if the iMPAKT App could take account of communication by text (evaluation workshops).

…you could describe this as a journey where at the beginning, we were, I suppose, really anxious. Then with the right level of support from Christine researcher and your own peer group you were able to really embrace it and see the benefits. (FG2 FNP1)

4 DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to explore the utility and feasibility of implementing eight person-centred nursing key performance indicators in supporting community nurses to lead the development of person-centred practice. The findings suggest that, on the whole, they are an effective means for community nurses to generate a range of evidence, grounded in service user experience of care. Findings also reinforced the potential for real-time reporting using the iMPAKT App, despite the technological challenges that were experienced during the implementation phase. Furthermore, the findings reflected the outcomes from previous implementation studies, highlighting the celebratory nature of implementing the KPIs as a process that can evidence the positive contribution of nursing and the potential to develop practice (McCance et al., 2015; McCance et al., 2020).

Evidence, leadership (as part of context) and facilitation were recognized as key elements to bringing about changes in practice by Kitson, Harvey, and McCormack (1998) in their original Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. The newly revised integrated framework (iPARIHS; Harvey & Kitson, 2016) pays more attention to the role recipients of the intervention, the implementation process and the wider sociopolitical context. The findings of this study reflect the need to focus on multiplicity of evidence considered by teams as relevant and their readiness to participate in change and the implementation process. Evidence in the context of the iPARIHS framework moves away from linear notions of research evidence having primacy. Instead, it focuses on multiple sources of evidence, including policy, clinical, patient and local evidence, being important to influencing changes in practice. Data gathered through the iMPAKT App permitted multiple sources of evidence generated from the eight KPIs, to be obtained and triangulated, making it more meaningful to community teams. The relevance of the data relating to evidence was reflected in the emergent themes, giving voice to experience and proud to be a nurse. The former theme is in line with the strategic context, where improving peoples' experience of care is a key goal of national policy (Bengoa, Stout, Scott, McAlinden, & Taylor, 2016). As highlighted in the theme proud to be a nurse, participants discussed feeling empowered by the evidence from the eight KPIs that not only helped them feel valued by colleagues, clients and families, but also illustrated the contribution of community nursing to the patient experience. In particular, hearing clients voices provided opportunities to celebrate, and also provided teams with clear indicators of where they needed to improve their practice. However, there was acknowledgement the data collected through the use of the iMPAKT App would be complementary to other sources of evidence, as reflected in previous studies (McCance et al., 2012, 2015; McCance & Wilson, 2016).

The iPARIHS framework also identifies inner and outer layers of context. The element of context encompasses the subthemes of leadership, culture and evaluation. The current outer layer or macro context advocates collective leadership (Department of Health & Social Care, 2019; West et al., 2015) as the model of shared responsibility currently being proposed in the UK. The person-centred nursing KPIs and the associated measurement framework do appear to offer a platform for this required change of mindset. Consistent with the findings of previous research (McCance et al., 2015), participants reported, in the inner layer of context, they created conditions where teams experienced empowerment and increased morale, which was a key driver in continuing to engage with the process of using the eight KPIs. This was reflected in the theme proud to be a nurse. Leading for cultural change demonstrates how this work can be a catalyst for culture change. Beginning to talk the language of person-centredness is indicative of a move towards more flourishing workplaces, which, according to McCormack, Dewing, and McCance (2011), are where person-centred cultures exist. Reflective of person-centred cultures, teams were intentional about hearing the voice of service users and co-designing and co-producing practice improvements around service user needs. Brun, O'Donovan, and McAuliffe (2019) suggest this is consistent with shared responsibility and collective leadership.

There were significant challenges for some teams who were unable to collect the required amount of data, despite agreement about the usefulness of the KPIs and the iMPAKT App. This also links to how the implementation process was supported. Although facilitating engagement suggests the support offered to participants was key to the success of this project, little attention was paid to facilitation expertise in the teams. Facilitation is viewed as the active ingredient in the iPARIHS framework that operationalizes the implementation of evidence. This is planned in response to the focus of the innovation or change matched with the needs of the recipients of that change, whilst acknowledging the context in which the change is being implemented. Whilst as facilitators we were able to determine the needs of participants in the context of the change being implemented (i.e. the use of the iMPAKT App), we had little ability to influence the contexts in which the App was being implemented.

4.1 Limitations

The small-scale nature of this feasibility study suggests that results should be generalized with caution. The lengthy ethical and governance approval process alongside issues with the readiness of the iMPAKT App reduced the time participants had to participate in the research. Not all teams managed to collect the required amount of data, although representatives from all teams agreed about the usefulness of the KPIs and the iMPAKT App. Only one cycle of data collection was possible, and the reports were not available in real time due to ongoing technological issues. There was an issue with the activity log component of the iMPAKT App where data did not save accurately to the master dashboard; however, teams kept a paper log of their activity for this component.

5 CONCLUSION

This study, conducted as part of a larger programme of research, has further shown the utility and robustness of the person-centred nursing KPIs and the measurement tools for use in community nursing. By adopting a collective leadership approach, teams were able to work together to decide on the data relevant for their practice area. There is potential for the iMPAKT App, which is considered user-friendly and easy-to-use, to help teams gather a range of data, privileging the voice of the service user. Facilitation is an important ingredient in strengthening leadership, which is central to enabling teams to work together to improve person-centred practice. In conclusion, this feasibility study provides many positive insights into the process of implementing the KPIs and accompanying measurement framework using the iMPAKT App, and provides a basis for considering a larger scale testing in the future.

6 IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

Person-centred KPI data, used alongside current quality indicators, provides an added layer of knowledge demonstrating how teams are working collectively to enhance the experience of care. The data generated can assist in the development or evaluation of new service models ensuring teams are working in line with key national policies surrounding person-centred care. It will allow nurse managers across different contexts to illustrate to key stakeholders how teams are working to deliver a high standard of care to people and how this care is being perceived by clients. Involving and engaging nurses at all levels in service development has been shown to enhance morale, teambuilding and leadership, creating the conditions for a flourishing workplace environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge all the staff across the participating organisations who committed time and energy to ensure the success of this study.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was sought and granted in line with research governance framework requirements across all jurisdictions. The ethical and governance approval process was led by Ulster University for all sites within the UK (Ulster University Ethics Committee, REF: 19/0014; and Office of Research Ethics Committee Northern Ireland, REF 19/NI/0045), with additional approvals required for Scotland (REF: R&D No: 2019/0099).