The Relationship Between Team Deep-Level Diversity and Team Performance: A Meta-Analysis of the Main Effect, Moderators, and Mediating Mechanisms

Abstract

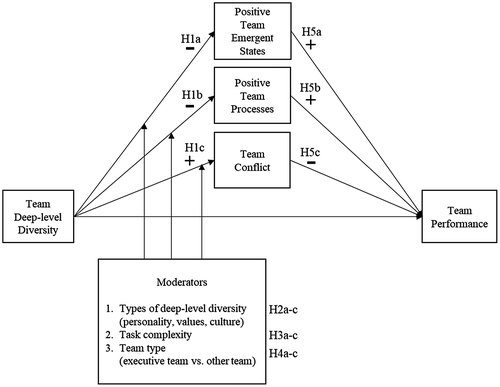

To reconcile the inconsistencies and complexities in the relationship between team diversity and performance, our meta-analysis takes a more nuanced approach to the relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance. We examine the type of deep-level diversity (personality, values, culture), task complexity, and executive team status as moderators of the relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict. In addition, we examine the mediating role of positive team emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict in explaining how team deep-level diversity relates to team performance. We test our hypotheses with a meta-analytic database of 94 papers reporting 280 effect sizes based on 24,425 teams. Findings show that team deep-level diversity is associated with fewer positive emergent states and positive team processes and more team conflict. There is an indirect relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance through each of the mediators: positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Collaborating in teams to fully utilize the knowledge and perspectives of diverse team members has become the cornerstone of modern-day organizations (Cross et al., 2016). As organizations become more diverse, it is important to understand how team diversity influences team performance, and the mechanisms by which this happens. Research on team diversity over the past few decades has generally fallen into one of three camps. The most frequently researched aspects of diversity are demographic (i.e., surface-level) diversity, defined as readily observable individual differences such as sex, race, and age (Harrison et al., 1998) and job-related diversity which includes education, work experience, and functional background (Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007). Several meta-analyses indicate that the relationship between team demographic diversity and team performance is very small and close to zero, while the relationship between job-related diversity and team performance is small yet positive (Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Joshi and Roh, 2009; Webber and Donahue, 2001). The third, less frequently investigated type of diversity is deep-level diversity (Mathieu et al., 2008), which refers to deep-seated differences such as personality, values, attitudes, and beliefs (Harrison et al., 2002; Riordan, 2000). Acknowledging the three different types of team diversity, we focus on the less-explored deep-level diversity in this research because it has closer and more direct relationships with both taskwork and teamwork in teams by influencing the way people process information. One study shows it also has longer-lasting effects on teams than demographic diversity (Harrison et al., 2002). Focusing on how and when team deep-level diversity matters, our research can contribute to the understanding of the more complex and nuanced effects of deep-level diversity on teams.

Since Bell’s (2007) important first step of conducting a meta-analysis to examine team deep-level composition (i.e., the association between mean levels of deep-level personality traits and team performance), meta-analyses have been conducted on team deep-level diversity. However, the studies have focused primarily on team performance as the outcome variable (Bell et al., 2011; Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Joshi and Roh, 2009; Peeters et al., 2006; van Dijk et al., 2012; Webber and Donahue, 2001). Specifically, focusing on one type of deep-level diversity, a meta-analysis by Stahl et al. (2010) examined the direct relationships between cultural diversity and team process constructs (e.g., conflict, communication, and satisfaction). Yet, none of the extant meta-analyses have examined the underlying mechanisms of how deep-level diversity relates to team performance. By studying the indirect effects of team deep-level diversity on team performance through different intervening variables, a more comprehensive understanding of team deep-level diversity will be possible.

Therefore, this study contributes to the team diversity literature by meta-analytically testing three potentially important mediators as explanatory mechanisms for the relationship between deep-level diversity and team performance. Recognizing the double-edged sword of team diversity (Milliken and Martins, 1996; van Knippenberg and Schippers, 2007; Williams and O’Reilly, 1998), we focus on mediating roles of team positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict in the deep-level diversity and team performance relationship. Team positive emergent states are defined as ‘properties of the team that are typically dynamic in nature and vary as a function of team context, inputs, processes, and outcomes’ (Marks et al., 2001, p. 357; e.g., team cohesion, collective efficacy, and team identification). Positive team processes include information sharing, collaboration, and coordination, while team conflict is a negative team process. Examining these variables permits the test of a comprehensive model examining the underlying mechanisms through which deep-level diversity relates to team performance. When there are inconclusive or contradictory findings in a literature, meta-analysis is a powerful tool that can help estimate true population effects and clarify the nature of boundary conditions and mechanisms using large sample sizes from many primary studies, which makes both a methodological and theoretical contribution.

In addition, this meta-analysis identifies important boundary conditions by investigating whether and how different moderators (i.e., type of deep-level diversity, task complexity, executive or non-executive teams) affect the magnitude of these relationships. In particular, by studying and comparing different forms of deep-level diversity – personality, values, and cultural diversity – as they relate to team positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict, we take a more fine-grained and extensive approach to team diversity. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of why and when some teams are more productive than others.

The results of such an effort are also potentially meaningful for organizations. Most organizations use teams to accomplish their work (Devine et al., 1999; Gordon, 1992; Mathieu et al., 2008), and the focus on teamwork has grown over the past two decades, both for practitioners (Cross et al., 2016) and for researchers (Wuchty et al., 2007). As organizations become increasingly diverse, it is important for researchers and practitioners to know what enables diverse teams to perform just as well as, if not better than, homogeneous teams.

THEORY DEVELOPMENT AND HYPOTHESES

Defining Key Constructs

Diversity represents differences between individuals on any given characteristic (Harrison and Klein, 2007). Researchers have distinguished demographic/surface-level diversity from deep-level diversity based on whether the characteristics are observable (Harrison et al., 1998). Consistent with prior research (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002; Riordan, 2000), in the present study, dimensions of deep-level diversity include personality (e.g., the Big Five traits, locus of control), values (i.e., life and work-related values and preferences), and culture (i.e., shared understandings which influence practices [the way things are done]; House et al., 2004).

Deep-level diversity influences team positive emergent states, positive team processes, team conflict and, ultimately, team performance (Driskell et al., 1987; Edwards et al., 2006; Hackman, 1987). Team positive emergent states (hereafter referred to as positive emergent states) refer to properties of the team that ‘vary as a function of team context, inputs, processes, and outcomes’ (Marks et al., 2001, p. 357). Marks et al. (2001, p. 358) describe emergent states as ‘products of team experiences’. This includes cognitive, affective, and motivational states. In the present study, positive emergent states include team cohesion, satisfaction with the team, commitment toward the team, identification with the team, and team potency. Positive team processes comprise collaboration, communication, cooperation, and information sharing, as well as helping others. In contrast to positive team processes, all forms of team conflict (i.e., relationship, process, and task conflict) are included in a separate category of disruptive/negative team processes (Marks et al., 2001). Two meta-analyses (De Dreu and Weingart, 2003; de Wit et al., 2012) show that all forms of conflict can indeed be disruptive, as they are damaging to team dynamics and team performance. Finally, team performance refers to how well a team accomplishes its task goals (Devine and Phillips, 2001).

Theoretical Perspectives Representing Negative and Positive Outcomes of Team Diversity

We begin by describing research representing both the negative (social categorization) and positive (information/decision-making) perspectives on diversity (i.e., van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams and O’Reilly, 1998). The social categorization perspective (consistent with the similarity-attraction paradigm) predicts that people are attracted to and have an easier time getting along with others similar to themselves (Byrne, 1971; Tajfel and Turner, 1986). This perspective has been termed a ‘pessimistic’ view of diversity (Mannix and Neale, 2005, p. 34) because differences are often expected to have negative effects on group processes and outcomes (Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Webber and Donahue, 2001; Williams and O'Reilly, 1998). Deep-level diversity can lead to process-related problems because differences among team members can create issues during the course of working together which will, in turn, decrease team performance. The social categorization perspective predicts that diverse teams will be less productive than homogenous teams because homogenous teams share similar attributes and work together more fluidly. Mutual attraction can make positive team processes, such as communication, more efficient, and team members may cooperate better with similar teammates than with dissimilar ones (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). For example, attitudinal similarity helps team processes through a better understanding of tasks and challenges in teams as well as by clarifying roles among team members (i.e., Tsui and O’Reilly, 1989).

In contrast to the social categorization perspective, the information/decision-making perspective predicts that team diversity, especially in job-related dimensions (e.g., education, work experience, and functional background), will lead to productive team processes because the information received from different perspectives yields a more comprehensive analysis of alternatives (Gruenfeld et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2004). Moreover, the information/decision-making perspective predicts that while job-related diversity in teams may result in challenges processing information as a result of differing perspectives, the challenges from managing a team with job-related diversity will nevertheless be overshadowed by the advantages obtained from having a richer pool of knowledge and information (Gruenfeld et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2004). Since job-related diversity yields relevant information for the work at hand (Drach-Zahavy and Somech, 2002; Keller, 1994), diverse teams have a broader pool of information and perspectives to utilize during decision-making. Similarly, deep-level diversity might yield various viewpoints and approaches, ultimately leading to greater insights and more thought-out decisions. However, process-wise, there is potential for it to create conflict and to adversely affect relationships between team members, which eventually hurts the team (Barsade et al., 2000; Harrison et al., 2002; Mohammed and Angell, 2003; Pinjani, 2007; Wageman and Gordon, 2005).

In the extant literature, the team diversity-performance relationship is inconclusive, particularly without consideration for more complex factors such as team members’ cognitive processes in stereotyping and temporal dynamics (Harrison and Klein, 2007; van Dijk et al., 2012, 2017; van Knippenberg and Schippers, 2007; Williams and O’Reilly, 1998). Therefore, we do not focus on the main effect between deep-level diversity and team performance, and instead, we focus on examining boundary conditions and underlying mechanisms of this relationship as called for by past research (e.g., van Knippenberg and Schippers, 2007).

Team Deep-Level Diversity and Positive Emergent States

According to social categorization theory, deep-level diversity will be negatively related to positive emergent states by creating the potential for friction in the team (Lim, 2003; Pinjani, 2007). For example, a highly conscientious person who strives to do her/his work meticulously could easily become irritated with another team member who is not as conscientious because of this personality difference (Barrick et al., 1998). Furthermore, members who value teamwork may have difficulty working with others who are less inclined to work in a team setting due to differences in values, which may result in fewer positive emergent states (e.g., cohesion, trust, and identification) (O'Reilly et al., 1991). Cultural diversity can have a similar effect on teams such that different ways of thinking (e.g., perceptions, beliefs, information-processing) and working due to diverse cultural backgrounds may lead to less cohesion or fewer emotional bonds within the team (Stahl et al., 2010).

Hypothesis 1a: Team deep-level diversity will be negatively related to team positive emergent states.

Deep-Level Diversity and Team Processes (Positive Team Processes and Team Conflict)

Next, we describe the relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes, as well as team conflict. Deep-level diversity can benefit teams when the information obtained from the varied perspectives results in a more comprehensive analysis of alternatives (van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams and O’Reilly, 1998). However, team processes occurring in teams with deep-level diversity may not always be smooth. Deep-level diversity represents fundamental differences in the way people process information and approach problems. The social categorization perspective argues that because individuals are more willing to work with and share knowledge with others who are similar, teams with such fundamental differences among members will experience process-related problems, including lack of communication and cooperation. Therefore, deep-level diversity can adversely impact positive team processes as it creates the potential for dysfunction (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002; Lim, 2003; Pinjani, 2007; van Knippenberg and Schippers, 2007).

Hypothesis 1b: Team deep-level diversity will be negatively related to positive team processes.

Hypothesis 1c: Team deep-level diversity will be positively related to team conflict.

Moderators of the Preceding Relationships

We further focus on the potential effects of three theoretically meaningful moderators – type of deep-level diversity, task complexity, and executive team status.

Type of deep-level diversity

We begin by proposing that the relationships between deep-level diversity and positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict are moderated by different types of deep-level diversity (i.e., personality, values, and culture). Personality is a representative individual disposition that influences broad ranges of trait-relevant responses (Mischel and Shoda, 1998; Ozer and Benet-Martinez, 2006). Values guide the way we live and the decisions we make; they involve judgments and evaluations of what is right and important to a person (Boer and Fischer, 2013; Gordon, 1972; Torelli and Kaikati, 2009). Culture influences one’s mind-set, behaviour, interactions, and understanding of others through socialization in a given culture’s shared patterns (e.g., Doney et al., 1998; Oyserman and Lee, 2008; Wood and Eagly, 2002). Values and culture are closely related because values may be developed through interaction with people and one’s environment (Bruce et al., 1989; Leung and Morris, 2015; Oyserman and Lee, 2008).

Personality, values, and culture influence one’s behaviours and interactions with others within a team since they are assumed to be relatively stable, enduring dispositions. However, values and culture guide our attitudes (defined as feelings or opinions about something or someone), are more evaluative in nature, and are directed at a given object or target (e.g., Boer and Fischer, 2013), while personality traits are not. Therefore, we propose that values and cultural diversity have the potential to create stronger effects in teams than personality diversity. In the literature, personality diversity relates to relationship conflict and affective reactions because of its nature (Mohammed and Angell, 2004; Tekleab and Quigley, 2014), whereas attitudinal similarity helps teams process information constructively and extensively because a similar understanding of tasks and challenges in teams can facilitate better communication and clarify roles among team members (Tsui and O’Reilly, 1989). Team members’ different values are detrimental to group processes (e.g., Jehn and Mannix, 2001; Wageman and Gordon, 2005), while value congruence helps team processes be more constructive and satisfying (Harrison et al., 1998; Jehn et al., 1997). Cultural diversity is also positively related to overall intragroup conflict (Vodosek, 2007) and process losses due to less effective communication and increased conflict (Stahl et al., 2010).

The impact of values and culture on group dynamics and team processes may also be explained by the team mental model, which is defined as team members’ shared and organized understanding of knowledge about their relevant environment (Johnson-Laird, 1983; Klimoski and Mohammed, 1994). Team members who share similar mental models will be more likely to anticipate the team task and expectations from other team members’ responses, which helps enhance effective communication and social support and reduce conflict. Therefore, team members can better coordinate their actions and adapt to task demands, which in turn enhances decision-making and team performance (Klimoski and Mohammed, 1994; Marks et al., 2001; Mathieu et al., 2000). Because personality represents individual dispositions, we propose that personality diversity is less likely to have deep-seated effects on team mental models compared to values and cultural diversity, which guide evaluations about what is fundamentally right, wrong, and to be expected (House et al., 2004).

Hypothesis 2: The type of deep-level diversity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and (a) positive team emergent states and (b) positive team processes such that the relationship will be stronger for values and cultural diversity compared to personality diversity.

Hypothesis 2c: The type of deep-level diversity will moderate the positive relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict such that the relationship will be stronger for values and cultural diversity compared to personality diversity.

Task complexity

Hypothesis 3a: Task complexity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and team positive emergent states such that the relationship will be stronger when task complexity is high rather than low.

Hypothesis 3b: Task complexity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes such that the relationship will be stronger as task complexity increases.

Hypothesis 3c: Task complexity will moderate the positive relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict such that the relationship will be stronger as task complexity increases.

Executive versus non-executive teams

In the study of organizations, upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason, 1984) explains that executives filter information from the environment using their own experience, values, and personality to make business decisions. The theory predicts that executives use their cognitive filters to process information and make decisions for the organization based on the best of their knowledge. Moreover, their best knowledge and judgment is determined by all of their characteristics and experiences, including their personality, their values, and their culture, as well as their demography and work experience.

‘when upper echelons researchers assert that executives matter, we don’t mean that they only matter positively. They matter for good and for ill. They sometimes do smart things and sometimes do dumb things. They sometimes deserve our applause and sometimes deserve our scorn. Executives make decisions and engage in behaviours that affect the health, wealth, and welfare of others – but they do so as flawed human beings’. (p. 341)

Hypothesis 4: Executive team type will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and (a) positive team emergent states and (b) positive team processes such that the relationships will be weaker for executive teams compared to non-executive teams.

Hypothesis 4c: Executive team type will moderate the positive relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict such that the relationship will be weaker for executive teams compared to non-executive teams.

Mediators of the Team Deep-Level Diversity to Team Performance Relationship

Hypothesis 5a: The relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance will be mediated by positive team emergent states.

Hypothesis 5b: The relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance will be mediated by positive team processes.

Finally, it is argued that relationship conflict mediates the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance. The prediction for the mediating role of task conflict in the relationship between deep-level diversity and team performance is complex because the literature shows mixed effects of team deep-level diversity on task conflict. In addition, research shows curvilinear relationships between task conflict and team functioning and performance; a moderate level of task conflict can help team processes and performance (De Dreu, 2006; Farh et al., 2010). The literature also reveals that the direction and strength of the relationship between task conflict and team performance varies depending on team members’ perceptions, such as psychological safety (Bradley et al., 2012), the association between task conflict and relationship conflict (De Dreu and Weingart, 2003), the measure of performance, or team characteristics (top management teams vs. non-top management teams) (de Wit et al., 2012). Taken together, the findings in the literature leave room for reconciliation around task conflict in a team setting.

Hypothesis 5c: The relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance will be mediated by team conflict.

Figure 1 presents an illustration of the conceptual model.

METHODS

Literature Search Procedures and Inclusion Criteria

A literature search was conducted to identify studies examining the relationships between deep-level diversity, positive emergent states, positive team processes, team conflict, and team performance. To ensure a comprehensive search, several procedures were used to retrieve both published and unpublished primary studies. First, we conducted a bibliographic search in PsycINFO, ABI/Inform, Business Source Complete, Sociological Abstracts, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses. We searched for divers*, difference*, heterogene*, OR demograph* AND group*, team*, OR work group*[[1]] in titles, abstracts, and key words to identify potentially relevant studies. We expanded the search for unpublished studies by reviewing programs and proceedings for the meetings of the Academy of Management, and the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology for 12 years (2006–19). We contacted the authors of the studies that were retained for inclusion in the present meta-analysis and emailed Academy of Management distribution lists to identify relevant unpublished papers. We also conducted a review of the reference lists of all previous team diversity review papers and meta-analyses (i.e., Bell et al., 2011; Bowers et al., 2000; Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Joshi and Roh, 2009; Peeters et al., 2006; van Dijk et al., 2012; Webber and Donahue, 2001; Williams and O’Reilly, 1998) to identify relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria for the present meta-analysis. Finally, we reviewed the references of the retained studies to identify additional relevant articles.

To be included in the present analysis, studies had to (a) report a relevant effect size of the relationships examined in the meta-analysis (Pearson r or a statistic that could be converted to Pearson r), (b) report the sample size on which the effect size was based, and (c) employ a team-, rather than individual-level of analysis. Thus, studies were excluded if there was no team-level effect size for the relationship of interest and/or if sufficient information to compute a correlation between diversity and team-level mediators and/or team performance was not reported. Additionally, to be included in the study, a primary study had to focus on deep-level diversity, include adults working in teams, and be written in English. These procedures identified approximately 710,578 articles that were screened for relevance. Of these, we were able to code 242 effect sizes from 79 papers.

In addition, we conducted a search on personality, values, and culture, and composition. The search was conducted in PsycINFO, ABI/Inform, Business Source Complete, Sociological Abstracts, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. The search for personality, values, and culture encompassed the entirety of each electronic database since its inception through June 19, 2019. The search for composition was conducted from April 1, 2006 until June 19, 2019, because Bell’s (2007) meta-analysis had searched for composition literature prior to April 1, 2006 and we have included every relevant composition article from Bell (2007). The search for personality, values, and culture resulted in 24,495 results while the search for composition resulted in 1,787 results. The results were screened for relevance, and in the end, 15 additional papers with 38 effect sizes met the criteria to be coded and were consequently retained. Therefore, the meta-analysis comprised a total of 280 effect sizes from 94 research reports.

The portion of the data set used to test Hypotheses 1-4, which pertained to the deep-level diversity to team performance relationship and the deep-level diversity to mediator (i.e., positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict) relationships, comprised 212 effect sizes (see the Appendix for study-level information). The remaining 68 effect sizes were for the relationships between the mediators and team performance which were used to test the mediation hypotheses (i.e., Hypotheses 5a-5c).

Variables from primary studies that comprised the deep-level diversity category were personality diversity, values diversity, or cultural diversity. Primary studies measured deep-level diversity in several different ways, including Blau’s index, standard deviation, variance, coefficient of variation, Euclidian distance, faultlines, and perceptual variables of differences. Variables from primary studies that comprised the positive emergent states category included cohesion, identification, affect, group norms, trust, team efficacy, and team potency. The positive team processes category is composed of studies measuring communication, collaboration, coordination, helping, and information sharing. The team conflict category is composed of task, relationship, and process conflict. Finally, the team performance category is composed of studies measuring task performance and goal accomplishment. Measures of team performance include productivity, accuracy, quality, quantity, and effectiveness. Studies included in the meta-analysis are indicated by an asterisk in the references section.

Coding Procedures and Inter-coder Agreement

Each study was coded for the following variables: (a) sample size (i.e., number of teams), (b) type of diversity, (c) correlations between diversity and relevant correlates, (d) reliability estimates for diversity and its correlates, and (e) sample characteristics. To ensure coding accuracy, three of the authors jointly developed a coding scheme based on the conceptual and operational definitions of the relevant constructs in the primary studies. Two of the authors coded 12 manuscripts initially, then checked their inter-coder agreement, discussed the discrepancies, and reached full agreement before proceeding. All article coders hold a PhD in management or are PhD candidates in management and have considerable experience reading and conducting research. Two of the authors coded all of the studies. Average inter-rater agreement was high (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.98). This average is based on coding all key variables from the studies in the meta-analysis, including sample size, independent variable reliability, dependent variable reliability, and sample characteristics (i.e., task complexity and team type). The variable with the greatest number of disagreements was task complexity, where inter-rater agreement was 0.95. To resolve these disagreements between two of the authors, a third author coded each of the articles and gave their opinion on the matter. All disagreements were resolved through discussion so final inter-coder agreement across all coded effect sizes was 100 per cent.

Based on different types of mediators (i.e., positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict), correlation coefficients were grouped into the following categories: deep-level diversity → positive emergent states (k = 55), deep-level diversity → positive team processes (k = 40), and deep-level diversity → team conflict (k = 25) as well as the category of deep-level diversity → team performance (k = 93). We also coded effect sizes for the following relationships in order to test for the hypothesized indirect effects: positive emergent states → team performance (k = 31), positive team processes → team performance (k = 21), and team conflict → team performance (k = 16.[[2]] If multiple correlation coefficients were reported in a study between team diversity and dependent variables grouped in the same outcome category (e.g., positive team processes), we aggregated them into a single linear composite correlation (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004). If an article provided insufficient information to compute the linear composite, effect sizes from the same dependent variable category were averaged together. These steps ensured independence in effect size estimates within outcome categories.

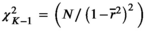

Meta-Analytical Techniques

Arthur et al.’s (2001) SAS PROC MEANS meta-analysis program was used to compute sample-weighted mean correlations ( ) following the procedures of Hunter and Schmidt (2004). We utilized random effects models in meta-analysis, consistent with the methodology of Hunter and Schmidt (2004), who explain that random effects models of meta-analysis are the more general models and allow for the possibility that the population parameter values vary between the studies included within the meta-analysis. By removing the variance across original effect size estimates due to sampling and measurement error, we estimated average true score correlations (ρ) within each outcome category. We used the artifact distribution method to correct for attenuation due to measurement error by correcting for unreliability in both the predictors and criteria (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004).[[3]] We computed 95% confidence intervals to measure the accuracy of the effect size estimates (Whitener, 1990).

) following the procedures of Hunter and Schmidt (2004). We utilized random effects models in meta-analysis, consistent with the methodology of Hunter and Schmidt (2004), who explain that random effects models of meta-analysis are the more general models and allow for the possibility that the population parameter values vary between the studies included within the meta-analysis. By removing the variance across original effect size estimates due to sampling and measurement error, we estimated average true score correlations (ρ) within each outcome category. We used the artifact distribution method to correct for attenuation due to measurement error by correcting for unreliability in both the predictors and criteria (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004).[[3]] We computed 95% confidence intervals to measure the accuracy of the effect size estimates (Whitener, 1990).

When examining moderation in meta-analysis, one must first have a conceptual justification to test for moderation, as we do in our moderation hypotheses. Once that has been satisfied, one empirically conducts a subgroup moderator analysis approach (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004) to test for moderators. This was accomplished by directly comparing the true score correlations for the subgroups of the moderator. Lower and upper 90 per cent credibility intervals were computed to examine the presence of potential moderators in the relationships. We checked the likelihood of moderation for each outcome category by following the ’75 per cent rule’ (i.e., moderators present if artifacts fail to explain 75 per cent or more of the observed variance) (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004), calculating 90 per cent credibility intervals around the estimated true score correlation (i.e., moderators present if interval includes zero or is relatively wide), and using chi-square tests of homogeneity (i.e., moderators present if statistically significant). These tests indicate whether the observed variance in effect sizes across studies was explained fully by statistical artifacts (i.e., average true score correlation, ρ, represents a single population parameter), or by systematic differences between studies in addition to within-study sampling variability (i.e., average true score correlation, ρ, represents the mean of parameters from several subpopulations). Hunter and Schmidt (2004, p. 90) explain that a moderator reveals itself when the ‘average correlation [varies] from subset to subset’ and ‘the corrected variance average[s] lower in the subsets than for the data as a whole.’ Thus, we computed the corrected variance for each outcome variable as well as for each subset by subtracting the variance attributable to statistical artifacts ( ) from the sample size weighted observed variance of correlations (

) from the sample size weighted observed variance of correlations ( ) as per Hunter and Schmidt (2004, p. 91). When conducting subgroup moderator analyses, which requires breaking the data into subgroups (representing levels of the moderator), there is evidence of moderation if the average of the corrected variance for the subgroups is smaller than the corrected variance for the data as a whole. A moderator is deemed to be meaningful if the confidence intervals constructed around each subset do not overlap.

) as per Hunter and Schmidt (2004, p. 91). When conducting subgroup moderator analyses, which requires breaking the data into subgroups (representing levels of the moderator), there is evidence of moderation if the average of the corrected variance for the subgroups is smaller than the corrected variance for the data as a whole. A moderator is deemed to be meaningful if the confidence intervals constructed around each subset do not overlap.

To test for mediation, we conducted path analyses in LISREL 8.80, following the meta-analysis structural equation modelling (SEM) approach described by Landis (2013). We estimated the path coefficients among variables that were relevant to each hypothesis using the mean true score correlations from the articles coded in this meta-analysis. The path coefficients for relationships pertaining to each hypothesis were used as inputs to the path analysis. The sample size used in the path analysis was the harmonic mean of the sample size N associated with each path in the corresponding model. This procedure is consistent with other meta-analyses testing for indirect effects (e.g., Earnest et al., 2011).

Publication Bias

Publication bias is a common concern with meta-analyses. Effect size estimates can be non-representative of the population if papers with small samples and statistically insignificant effects are more likely to be missing (Kepes et al., 2012). Although we solicited unpublished manuscripts and reviewed 12 years of conference programs, there is a potential for publication bias in our results. We tested for publication bias using the PUB_BIAS macro for SAS written by Rendina-Gobioff and Kromrey (2006). This macro computes the Begg Rank Correlation, Egger Regression, Funnel Plot Regression, and Trim and Fill procedures[[4]] and has been used in other meta-analyses (e.g., Sayo et al., 2012; Leung and Morris, 2015). Each method uses a different approach to test for publication bias (for details, see Begg and Mazumdar, 1994; Duval and Tweedie, 2000a, 2000b; Egger et al., 1997; Macaskill et al., 2001).

Of the statistics, 28 out of 28 showed no publication bias, since the null hypothesis of no publication bias was not rejected. For deep-level diversity and team performance, 7 out of 7 results showed no publication bias (Egger Regression t = 0.12, p = 0.91; Begg Rank Correlation using variance z = −0.71, p = 0.48; Begg Rank Correlation using sample size z = 0.59, p = 0.55; Funnel Plot Regression t = 1.35, p = 0.18; Trim and Fill method showed no publication bias on the right tail, left tail, and both tail indicators). For each of the three relationships between deep-level diversity and (a) positive emergent states, (b) positive team processes, and (c) team conflict, 7 out of 7 results showed no publication bias. Statistics for the latter tests were omitted for brevity but are available upon request. Overall, publication bias was not a concern in this meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Table I reports the results of the meta-analyses examining the correlates of team deep-level diversity. We report sample-weighted mean correlations ( ), estimated mean true score correlations (ρ), variance attributable to statistical artifacts (

), estimated mean true score correlations (ρ), variance attributable to statistical artifacts ( ), sample size weighted observed variance of correlations (

), sample size weighted observed variance of correlations ( ), the percentage of variance across studies attributable to study artifacts, 95% confidence intervals, and 90 per cent credibility intervals. As Table I shows, the confidence interval for the effect size between team deep-level diversity and team performance (ρ = −0.01) includes zero. Our estimated mean true score correlation between team deep-level diversity and team performance is similar to effect sizes obtained in other meta-analyses including van Dijk et al. (2012) reporting a mean weighted effect size of −0.01 between deep-level diversity and team performance, Bell’s (2007) sample weighted mean correlations of personality heterogeneity and team performance ranging from −0.03 to 0.03, and Stahl et al.’s (2010) weighted mean effect size between cultural diversity and team performance of −0.02.

), the percentage of variance across studies attributable to study artifacts, 95% confidence intervals, and 90 per cent credibility intervals. As Table I shows, the confidence interval for the effect size between team deep-level diversity and team performance (ρ = −0.01) includes zero. Our estimated mean true score correlation between team deep-level diversity and team performance is similar to effect sizes obtained in other meta-analyses including van Dijk et al. (2012) reporting a mean weighted effect size of −0.01 between deep-level diversity and team performance, Bell’s (2007) sample weighted mean correlations of personality heterogeneity and team performance ranging from −0.03 to 0.03, and Stahl et al.’s (2010) weighted mean effect size between cultural diversity and team performance of −0.02.

| Team Outcome | N | k |

|

|

95% confidence interval | ρ |

|

% variance due to artifacts | χ2 test | 90% credibility interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team Task Performance | 7,781 | 93 | −0.01 | 0.027 | −0.03:0.01 | −0.01 | 0.012 | 44.14% | 210.68*** | −0.26:0.23 |

| Positive Emergent States (H1a) | 5,408 | 55 | −0.07 | 0.044 | −0.10: −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.010 | 23.13% | 237.81*** | −0.45:0.27 |

| Positive Team Processes (H1b) | 2,943 | 40 | −0.10 | 0.063 | −0.14: −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.013 | 21.47% | 186.28*** | −0.58:0.32 |

| Team Conflict (H1c) | 1,682 | 25 | 0.12 | 0.036 | 0.07:0.16 | 0.14 | 0.015 | 40.60% | 61.58*** | −0.15:0.43 |

-

N = no. of teams; k = no. of correlations;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;  = sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using

= sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using  and standard error based on sampling error variance

and standard error based on sampling error variance  when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using

when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using  and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;

and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;  = variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

= variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

- *** p < 0.001.

Team deep-level diversity is negatively related to positive emergent states (ρ = −0.09) and to positive team processes (ρ = −0.13), and the confidence intervals do not include zero. Thus, Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b are supported. Hypothesis 1c is also supported as the relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict is positive (ρ = 0.14) and the confidence interval does not include zero. As Table I shows, the effects indicate that less than 75 per cent of the variance is accounted for, the credibility values are wide, and the chi squares are significant, which indicates the presence of moderators. Therefore, coupled with the theoretical basis for testing moderators, we proceed to test for moderation.

Moderator Analysis

Type of team deep-level diversity

The meta-analytic results of three different deep-level diversity dimensions (i.e., personality, values, and culture) are shown in Table II. Hypothesis 2a posited that the type of deep-level diversity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive emergent states such that the relationship will be stronger for values and cultural diversity than for personality diversity. The effect size was more strongly negative for values diversity (ρ = −0.12) than for personality diversity (ρ = −0.07). However, the effect size for cultural diversity (ρ = −0.03) was weaker than that of personality diversity (ρ = −0.07). The average corrected variance for the subsets of three different deep-level diversity dimensions (0.027) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to positive emergent states as a whole (0.034), showing support for moderation. Taken together, Hypothesis 2a is partially supported such that the negative relationship between deep-level diversity and positive emergent states is stronger for values diversity than for personality diversity. However, the practical meaning of this effect is modest, because the 95% confidence intervals overlap for values and personality diversity.

| N | k |

|

|

95% confidence interval | ρ |

|

% variance due to artifacts | χ2 test | 90% credibility interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emergent States | ||||||||||

| Deep-level Diversity | 5,408 | 55 | −0.07 | 0.044 | −0.10: −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.010 | 23.13% | 237.81*** | −0.45:0.27 |

| Personality Diversity | 2,088 | 24 | −0.06 | 0.028 | −0.10: −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.012 | 41.16% | 58.31*** | −0.32:0.18 |

| Values Diversity | 2,688 | 22 | −0.10 | 0.045 | −0.14: −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.008 | 18.19% | 120.97*** | −0.49:0.26 |

| Cultural Diversity | 632 | 9 | −0.02 | 0.088 | −0.10:0.06 | −0.03 | 0.014 | 16.41% | 54.86*** | −0.56:0.51 |

| Positive Team Processes | ||||||||||

| Deep-level Diversity | 2,943 | 40 | −0.10 | 0.063 | −0.14: −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.013 | 21.47% | 186.28*** | −0.58:0.32 |

| Personality Diversity | 1,238 | 17 | 0.03 | 0.020 | −0.03:0.08 | 0.03 | 0.014 | 70.56% | 24.09 | −0.12:0.19 |

| Values Diversity | 1,318 | 17 | −0.26 | 0.046 | −0.31: −0.21 | −0.33 | 0.011 | 25.03% | 67.92*** | −0.70:0.05 |

| Cultural Diversity | 387 | 6 | 0.03 | 0.103 | −0.07:0.13 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 15.32% | 39.16*** | −0.57:0.63 |

| Team Conflict | ||||||||||

| Deep-level Diversity | 1,682 | 25 | 0.12 | 0.036 | 0.07:0.16 | 0.14 | 0.015 | 40.60% | 61.58*** | −0.15:0.43 |

| Personality Diversity | 992 | 13 | 0.05 | 0.018 | −0.01:0.12 | 0.06 | 0.014 | 79.81% | 16.29 | −0.06:0.18 |

| Values Diversity | 395 | 7 | 0.16 | 0.059 | 0.06:0.25 | 0.19 | 0.017 | 29.11% | 24.04*** | −0.22:0.60 |

| Cultural Diversity | 365 | 5 | 0.24 | 0.030 | 0.14:0.34 | 0.29 | 0.012 | 41.49% | 12.05 | 0.03:0.55 |

-

N = no. of teams; k = no. of correlations;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;  = sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using

= sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using  and standard error based on sampling error variance

and standard error based on sampling error variance  when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using

when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using  and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;

and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;  = variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

= variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

- *** p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 2b proposed that the type of deep-level diversity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes such that the relationship will be stronger for values and cultural diversity compared to personality diversity. The effect size was more strongly negative for values diversity (ρ = −0.33) than for personality diversity (ρ = 0.03). The effect size for cultural diversity (ρ = 0.03) was very similar to that for personality diversity (ρ = 0.03). The average corrected variance for the subsets of three different deep-level diversity dimensions (0.020) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to positive team processes as a whole (0.050), indicating moderation. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is partly supported such that the negative relationship between deep-level diversity and positive team processes is stronger for values diversity compared to personality diversity. This finding is also meaningful, as the 95% confidence intervals for values and personality diversity do not overlap.

Hypothesis 2c predicted that the positive relationship between deep-level diversity and team conflict will be stronger for values and cultural diversity than for personality diversity. Consistent with the hypothesis, the effect size was more strongly positive for values diversity (ρ = 0.19) and for cultural diversity (ρ = 0.29) compared to that of personality diversity (ρ = 0.06). However, the average corrected variance for the subsets of the three different dimensions of deep-level diversity (0.023) was larger than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to team conflict as a whole (0.022), not supporting moderation. Hypothesis 2c is not supported.

Task Complexity

Table III presents the meta-analytic results for the moderating role of task complexity. Hypothesis 3a suggested that task complexity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive emergent states such that the relationship will be stronger for teams with high task complexity than for those with low task complexity. The effect size was more strongly negative in high task complexity teams (ρ = −0.08) than in low task complexity teams (ρ = −0.00). The average corrected variance for the subsets of low and high task complexity teams (0.024) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to emergent states as a whole (0.034), indicating moderation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3a is supported. However, the practical difference between the subsets may be limited, as the 95% confidence intervals for high and low complexity overlap.

| N | k |

|

|

95% confidence interval | ρ |

|

% variance due to artifacts | χ2 test | 90% credibility interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emergent States | ||||||||||

| All | 5,408a | 55 | −0.07 | 0.044 | −0.10: −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.010 | 23.13% | 237.81*** | −0.45:0.27 |

| Low Task complexity | 2,150 | 16 | −0.00 | 0.026 | −0.05:0.04 | −0.00 | 0.007 | 28.69% | 55.77*** | −0.27:0.26 |

| High Task complexity | 2,234 | 28 | −0.07 | 0.042 | −0.11: −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.013 | 30.04% | 93.22*** | −0.42:0.25 |

| Positive Team Processes | ||||||||||

| All | 2,943a | 40 | −0.10 | 0.063 | −0.14: −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.013 | 21.47% | 186.28*** | −0.58:0.32 |

| Low Task complexity | 691 | 12 | −0.01 | 0.063 | −0.08:0.07 | −0.01 | 0.018 | 27.85% | 43.10*** | −0.44:0.43 |

| High Task complexity | 1,938 | 24 | −0.14 | 0.064 | −0.19: −0.10 | −0.18 | 0.012 | 18.79% | 127.72*** | −0.64:0.29 |

| Team Conflict | ||||||||||

| All | 1,682a | 25 | 0.12 | 0.036 | 0.07:0.16 | 0.14 | 0.015 | 40.60% | 61.58*** | −0.15:0.43 |

| Low Task complexity | 405 | 6 | 0.18 | 0.015 | 0.09:0.28 | 0.22 | 0.014 | 93.60% | 6.41 | 0.16:0.28 |

| High Task complexity | 1,098 | 14 | 0.13 | 0.031 | 0.07:0.19 | 0.16 | 0.012 | 40.97% | 34.17*** | −0.11:0.42 |

-

N = no. of teams; k = no. of correlations;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;  = sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using

= sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 95% confidence intervals have been calculated using  and standard error based on sampling error variance

and standard error based on sampling error variance  when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using

when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using  and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;

and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;  = variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

= variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

- a Several papers presented teams working on various different tasks, and complexity could not be clearly coded into high or low. This is why N and k do not add up between the subsets and the ‘All’ total.

- *** p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 3b proposed that task complexity will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes such that the relationship will be stronger for teams working on highly complex tasks than for those with simple tasks. The effect size was more negative in high task complexity teams (ρ = −0.18) than in other teams (ρ = −0.01). The average corrected variance for the subsets of low and high task complexity teams (0.049) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to positive team processes as a whole (0.050), indicating moderation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3b was supported. Moreover, the magnitude of the findings appears to be meaningful, as the 95% confidence intervals for high and low task complexity do not overlap.

Hypothesis 3c predicted that the positive relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict will be stronger for teams with high task complexity than for others with low task complexity. The effect size was more strongly positive in low task complexity teams (ρ = 0.22) than in high task complexity teams (ρ = 0.16). Thus, Hypothesis 3c is not supported. Also, the practical meaning of these findings seems limited, as the 95% confidence intervals for high and low task complexity overlap.

Executive versus Non-Executive Team

The meta-analytic results comparing executive and non-executive teams are presented in Table IV. Hypothesis 4a proposed that team type will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive emergent states such that the relationship will be weaker for executive teams compared to other teams. However, the effect size was more strongly negative in executive teams (ρ = −0.26) than in other teams (ρ = −0.07). The average corrected variance for the subsets of executive and other teams (0.024) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to emergent states as a whole (0.034), indicating moderation. Thus, Hypothesis 4a is not supported. Moreover, the magnitude of the moderation appears meaningful because the 95% confidence intervals do not overlap for the executive and non-executive teams.

| N | k |

|

|

95% confidence interval | ρ |

|

% variance due to artifacts | χ2 test | 90% credibility interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emergent States | ||||||||||

| All | 5,408 | 55b | −0.07 | 0.044 | −0.10: −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.010 | 23.13% | 237.81*** | −0.45:0.27 |

| Executive Team | 536 | 7 | −0.22 | 0.027 | −0.30: −0.14 | −0.26 | 0.012 | 44.58% | 15.70** | −0.51: −0.02 |

| Non-Executive Team | 4,864 | 47 | −0.06 | 0.043 | −0.09: −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.010 | 22.69% | 207.14*** | −0.43:0.29 |

| Positive Team Processes | ||||||||||

| All | 2,943 | 40 | −0.10 | 0.063 | −0.14: −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.013 | 21.47% | 186.28*** | −0.58:0.32 |

| Executive Team | 880 | 9 | −0.30 | 0.039 | −0.36: −0.24 | −0.37 | 0.009 | 22.76% | 39.55*** | −0.72: −0.01 |

| Non-Executive Team | 2,063 | 31 | −0.02 | 0.050 | −0.06:0.02 | −0.03 | 0.015 | 30.31% | 102.27*** | −0.41:0.36 |

| Team Conflict | ||||||||||

| All | 1,682 | 25 | 0.12 | 0.036 | 0.07:0.16 | 0.14 | 0.015 | 40.60% | 61.58*** | −0.15:0.43 |

| Executive Team | 266 | 4 | 0.24 | 0.007 | 0.13:0.35 | 0.29 | 0.014 | 185.72% a | 2.15 | 0.29:0.29 |

| Non-Executive Team | 1,416 | 21 | 0.09 | 0.038 | 0.04:0.15 | 0.11 | 0.015 | 38.66% | 54.32*** | −0.19:0.42 |

-

N = no. of teams; k = no. of correlations;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;

= sample size weighted mean observed correlation;  = sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 90% confidence intervals have been calculated using

= sample size weighted observed variance of correlations; 90% confidence intervals have been calculated using  and standard error based on sampling error variance

and standard error based on sampling error variance  when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using

when population effect size variance is zero (i.e., homogeneous) or using  and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;

and standard error based on the residual variance of correlations after removing sampling error variance (i.e., heterogeneous) (Whitener, 1990); ρ = mean true score correlation;  = variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

= variance attributable to statistical artifacts;

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

tests homogeneity of correlations (i.e., whether the residual variance is significantly large); 90 per cent credibility intervals have been calculated using ρ and the standard deviation of ρ.

- a Percentage of variance due to artifacts was actually greater than 100 per cent since the Hunter and Schmidt method tends to overestimate the amount of variance due to sampling error when k and N are small (Brannick and Hall, 2001).

- b One paper did not provide any information on the type of team (i.e., executive or employee team).

- ** p < 0.01;

- *** p < 0.001.

Similarly, Hypothesis 4b predicted that team type will moderate the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes such that the relationship will be weaker for executive teams compared to other teams. Nevertheless, the effect size was more negative in executive teams (ρ = −0.37) than in other teams (ρ = −0.03). The average corrected variance for the subsets of executive and other teams (0.033) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to positive team processes as a whole (0.050), which indicates moderation. Therefore, Hypothesis 4b is not supported. Again, the magnitude of the moderation seems practically meaningful because the 95% confidence intervals do not overlap for the executive and non-executive teams.

For the relationship between team deep-level diversity and team conflict, the effect size was more strongly positive in executive teams (ρ = 0.29) than in other teams (ρ = 0.11). The average corrected variance for the subsets of executive and other teams (0.012) was smaller than the corrected variance for the deep-level diversity to team conflict as a whole (0.022), showing moderation. Thus, Hypothesis 4c is not supported. The magnitude of the moderating effect does not appear to be meaningful, because the 95% confidence intervals overlap for the executive and non-executive teams.

Overall, results support the opposite of our predictions. Executive teams may, in fact, be more susceptible to the downsides of team deep-level diversity than non-executive teams.

Mediation Analysis

To test for the mediation predicted in Hypotheses 5a-5c, we used the mean true score correlations for the path between deep-level diversity and positive emergent states, between deep-level diversity and positive team processes, between deep-level diversity and team conflict, and between deep-level diversity and team performance (all from Table I). We obtained the mean true score correlation estimates between positive emergent states and team performance (ρ = 0.31, k = 31), between positive team processes and team performance (ρ = 0.36, k = 21), and between team conflict and team performance (ρ = −0.20, k = 16) from the articles coded in this meta-analysis that measured those relationships.

Hypothesis 5 posited that the relationship between deep-level diversity and team performance will be mediated by (a) positive emergent states, (b) positive team processes, and (c) team conflict. Results of the path analysis show that the indirect effect of deep-level diversity on team performance through positive emergent states is −0.03, z = −6.23, p < 0.01. The 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect ranges from −0.036 to −0.020 which does not include zero. Thus, Hypothesis 5a is supported. Similarly, the indirect effect of deep-level diversity on team performance through positive team processes is −0.05, z = −6.71, p < 0.01. The 95% confidence interval around this indirect effect ranges from −0.061 to −0.033 which does not include zero, supporting Hypothesis 5b. The indirect effect of deep-level diversity on team performance through team conflict is −0.03, z = −5.03, p < 0.01, and the 95% confidence interval ranges from −0.040 to −0.016, not including zero. Therefore, Hypothesis 5c is supported.

Post-Hoc Supplemental Analyses

In post-hoc analyses, we conducted additional moderator tests using team size, team type (student vs. non-student), type of publication (published vs. unpublished work), and year of publication. The results either showed no evidence of moderation or inconsistent evidence of moderation across the various team outcomes. Therefore, these results were omitted from the manuscript to keep the length of the paper reasonable. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon request.

DISCUSSION

Theoretical Implications

This research provides meaningful theoretical implications by testing and extending the similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971), as well as aspects of the more recent MIDST model (van Dijk et al., 2017) with respect to team diversity. Partial support for both theories is found. The positive relationship between deep-level diversity and team conflict was mitigated in high complexity tasks, which does not support the MIDST suggestion that social categories will be more salient when tasks are difficult and the focus is on all the information needs of the team. However, complex tasks did not help (but actually exacerbated) the negative relationship between team deep-level diversity and positive team processes, which is in line with the more pessimistic MIDST (van Dijk et al., 2017) and similarity-attraction predictions (Byrne, 1971). The results also indicate that the similarity-attraction paradigm could be adapted to consider variations among different types of team deep-level diversity. The findings of the moderator analyses examining the type of deep-level diversity (i.e., personality, values, culture) suggest that some forms of diversity create more dysfunction than others. Diversity of values seems to be more difficult for teams to overcome and yields fewer positive team emergent states and team processes compared to personality and cultural diversity. However, with regard to team conflict, cultural diversity was associated with the most conflict. Therefore, not all forms of deep-level diversity result in the same outcomes, and the similarity-attraction paradigm could be modified to account for that in its predictions. Results suggest that there is value in calculating the effect size for different components of deep-level diversity because they behave differently. The present research thus contributes to resolving the inconsistent findings regarding team diversity by teasing out the effects of different forms of deep-level diversity (i.e., personality, values, and cultural diversity).

Existing meta-analyses in the literature have mainly focused on the relationship between team demographic diversity and team performance and have found very small (close to zero) effect sizes (Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Joshi and Roh, 2009; Webber and Donahue, 2001). These findings imply that there is a need for studies to examine different dimensions of diversity and team outcomes (Bell et al., 2011) as well as the mechanisms by which the diversity to team performance relationship functions. The present study, therefore, expands the literature by examining deep-level diversity and its relationship with team performance through three underlying mechanisms (i.e., positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict). This helps resolve inconsistencies in the literature by elucidating on why diversity is related to team performance and the mechanisms through which it operates.

We also find that upper echelons theory may need to emphasize the point that executives are just as prone to flaws and human drama as are non-executive employees (Hambrick, 2007). Executive teams exhibited stronger negative effect sizes between team deep-level diversity and positive emergent states as well as positive team processes, and stronger positive effect sizes with team conflict, compared to non-executive teams. Therefore, although executives have reached the apex of an organization, they appear to be more susceptible to team dysfunction than members of other teams. The results are unexpected and counterintuitive since leveraging diverse viewpoints and enhancing team members' ability to work together to address complex business challenges should be the critical foundations for effective functions of executive teams. To be fair, we should also acknowledge that executives in the upper echelons are also working on complex matters which makes their tasks challenging to begin with.

Finally, the present study also has implications for the study of diversity in teams. Research conducted by Harrison and colleagues differentiated between demographic/surface-level and deep-level diversity in teams, finding that the effects of surface-level diversity on team outcomes weaken as time passes, while the effects of deep-level diversity on team outcomes strengthen (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002). This conveys the impression that deep-level diversity will have greater, more substantial effects on team outcomes. However, we further refine this thinking by demonstrating that not all forms of deep-level diversity are the same. In particular, values diversity displays the strongest detrimental effects on positive team processes, while cultural diversity and values diversity both exhibit stronger associations with team conflict compared to personality diversity. Overall, personality diversity exhibited very small effect sizes with positive emergent states, positive team processes, and team conflict in this meta-analysis. Therefore, not all forms of deep-level diversity can be seen and treated as interchangeable. Future research can unpack how different forms of deep-level diversity unfold in teams.

Practical Implications

The findings of the present study provide meaningful and noteworthy implications for managing diverse teams. Managers should consider taking a two-pronged approach to mitigating the issues caused by deep-level diversity in teams. First, wherever possible, managers may limit the amount of deep-level diversity that could be contentious in team settings. For example, if certain individuals are known to have clashing personality traits, culture, or values, managers may avoid assigning those people to the same team. If those differences would serve no purpose toward accomplishing the team’s task, they would likely do more harm than good. In real work settings, however, it is extremely difficult to consider all team members’ characteristics when assigning an individual into a team. Organizations may not have such information available, and even if they do have such information, managers are likely not allowed access to much of it due to employee privacy issues. More importantly, most organizations do not have enough resources to ignore prioritizing an effective mix of expertise, skills, and ability when forming a team. Based on our findings, we advise organizations to pay more attention to values and cultural diversity in teams – and less so personality diversity – in order to better understand how team members interact and respond to specific ideas, objects, persons, or situations. This, in turn, may lead to a team with better positive team processes and lower team conflicts through increasing process gains and reducing process losses even in teams with value and cultural differences. Team building workshops focusing on how to effectively avoid and constructively capitalize on conflict within a team could be one good practice for such effort. Second, managers could provide employees (especially those who have had conflicts with others) with more developmental feedback so that they may work more productively with people who are different from themselves (Thompson, 2011). Establishing clear ground rules in work processes and emphasizing decision-making criteria or setting the tone and expectations with pre-communication may enhance positive team dynamics and potentially prevent negative interactions among employees within a team.

Our results also suggest that teams in the upper echelons of organizations are just as susceptible to team problems as lower-level teams. In contrast to our predictions, teams in the upper echelons appear to experience stronger process-related challenges as a result of deep-level diversity compared to their lower-level counterparts. Research shows that executives sometimes suffer from hubris, and decisions driven by hubris may harm organizational performance (Kroll et al., 2000). This means that interventions and support for top management teams may be critical because mistakes and dysfunction at the higher levels have greater consequences for organizational performance. For example, executive team coaching for better mutual understanding and synthesis of diverse viewpoints may be one way to improve team dynamics, efficiency, and design. The findings also insinuate the importance of a chief executive officer (CEO)’s role in building a great leadership team and capitalizing on diversity within the team in order to maximize process gains, and in turn lead to better decision-making. Thus, developing CEOs’ people-managing skills and having effective team building for executive teams should be emphasized, and organizations should provide the necessary support.

Finally, in an effort to put our effect sizes into context and provide an example managers can take away, we note that in Table I, the effect sizes range from −0.09 to 0.14. Whereas on the surface these effects might seem small, it is important for managers to consider the context. For example, in a semester-long student team project, an effect size of 0.14 would explain 1.96 per cent of the variance in team conflict, which seems trivial. However, if the context were a NASA space mission to Mars with astronauts who are sequestered inside the space craft for years, a conflict of 0.14 may be more meaningful to the mission because of the human toll and its effect on a scientific exploration mission that costs billions of taxpayer dollars.

Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of the present study provide directions for future research. First, while our conceptual model (Figure 1) tests for mediation and implies a causal ordering between the model’s variables (i.e., deep-level diversity to positive emergent states, positive team processes, team conflict, and team performance), none of the studies in our meta-analytic sample measured these variables in a manner where each variable was measured at a different point in time. Specifically, whereas many studies in our sample (30 of the 94 research reports coded) measured variables at multiple points in time – especially with deep-level diversity, positive emergent states, and positive team processes prior to team performance – no study measured all the variables represented in our conceptual model at different points in time. Thus, future research should test for the causal ordering of the variables in our model as more longitudinal studies are conducted with measurements at multiple times. Since effects of team diversity may vary according to temporal factors, capturing both short- and long-term effects would provide a fuller picture of the relationship between team diversity and team effectiveness (Srikanth et al., 2016). Furthermore, taking temporal factors into consideration can increase our insight into team deep-level diversity by empirically testing a more complicated model around team dynamics and effectiveness, such as the input-mediator-output-input (IMOI) model (Ilgen et al., 2005; Langfred, 2007; Marks et al., 2001).

Second, future research should clarify why values diversity has stronger effects than personality and cultural diversity. These findings may have something to do with the attributions people make about the degree of controllability of that characteristic. For example, one cannot control the culture one has been born into. Similarly, personality research shows that personality is considered a trait that is fairly stable over time (McCrae and Costa, 1994). However, as we have seen over time with social movements such as the women’s rights movement, the civil rights movement, or the gay rights movement, people’s values can change over time as social attitudes evolve. In this sense, it appears that across the three forms of deep-level diversity we examined, values may be the one where other team members find the focal team member most culpable. Perhaps this is why values diversity consistently has stronger effects on positive emergent states, positive team processes, and conflict. Future research will tell.

Third, future research should consider other types of deep-level diversity as they relate to positive team emergent states, positive team processes, team conflict, and team performance. We focused on personality, values, and culture not only because they are the most studied but also because they are theoretically and practically important dimensions of deep-level diversity in organizations. Nevertheless, other types of deep-level diversity – such as beliefs about workplace ethics and work-related attitudes like leader-member exchange (LMX) differentiation – are also relevant to organizations. As more primary studies expand on the dimensions of deep-level diversity, future research could provide a more fine-grained and comprehensive picture of the impact of deep-level diversity on team outcomes. Deep-level diversity likely has both positive and negative influences on team processes and outcomes which have yet to be determined.

Fourth, we posit the mediating role of team conflict in the relationship between team deep-level diversity and team performance as linear and straightforward. We propose this hypothesis based on differing theoretical predictions (similarity-attraction paradigm vs. information/decision-making perspective) and empirical support from meta-analytic findings that any type of intragroup conflict leads to lower team performance (De Dreu and Weingart, 2003; de Wit et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the equivocal findings of many primary studies (Bradley et al., 2012; De Dreu, 2006; Farh et al., 2010) raise the possibility of additional boundary conditions (e.g., type of conflict, measure of performance, team characteristic) as well as potential curvilinear effects. Accordingly, future research should delve further into how and when team performance is helped or hindered by team conflict.

Fifth, some of the moderator analyses were based on small ks for some of the subgroups. This is especially true for executive teams predicting team conflict and for cultural diversity predicting team conflict where ks were 4 and 5, respectively. These results should be interpreted with caution given the limited number of data points, and future research should re-examine these results as more data points become available.

Future research may also examine more boundary conditions pertaining to the association between deep-level diversity, positive emergent states, positive team process, team conflict, and team performance. Results show that executive teams are susceptible to the same negative aspects of team deep-level diversity as non-executive teams, in contrast to our predictions. In fact, while Hambrick (2007) suggested that people in the upper echelons of organizations are just as susceptible to problems as everyone else working in lower-level occupations, our findings extend this because they are not like others. They are worse according to our data. Why might that be the case? Executives’ actions are sometimes driven by hubris (Kroll et al., 2000) and anecdotal examples tell us that people in high places sometimes have overdeveloped egos or do not want to admit fault. We do not measure this and, therefore, make no claims of knowing exactly why our data show that executive teams have worse reactions than lower-level teams. Future research can examine additional boundary conditions based on theory to provide more nuanced knowledge of team diversity and executives serving on top management teams and boards of directors.