Toward a Cognitive View of Signalling Theory: Individual Attention and Signal Set Interpretation

ABSTRACT

Research on organizational signalling tends to focus on the effects of isolated or congruent signals, assuming highly rational responses to those signals. In this study, we theorize about the cognitive processes associated with the attention paid to and interpretation of multiple, often incongruent signals that organizations send to consumers, financiers, and other stakeholders who make organizational assessments. Contributing a cognitive perspective of signal attention and interpretation, alongside the introduction of signal sets, we provide a more complete picture of how organizational signalling unfolds in the field. Our research opens new frontiers for future inquiry into the cognitive foundations of signal attention, multi-signal interpretation, and incongruent signals.

INTRODUCTION

Signalling theory (Spence, 1974) has proven to be an impactful theoretical lens to understand how organizational outsiders, such as prospective consumers or equity investors, go about assessing the quality of a business (e.g., Certo, 2003; Drover et al., 2017; Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009; Plummer et al., 2016; Reuer et al., 2012; Stuart et al., 1999). This perspective argues that because organizational quality cannot be directly observed, decision-makers must rely on information signals thought to correlate with quality (Bergh et al., 2014; Pollock et al., 2010). This means that evaluators search for signals, such as the founder's credentials, that can be used to make inferences about an organization's underlying quality. As such, signalling theory has proven to be useful in the organizational realm because it explains how a venture's attributes and actions communicate signals to outsiders about its quality and potential (see Higgins and Gulati, 2006; Hsu, 2007; Kirsch et al., 2009; Nam et al., 2014; Park and Patel, 2015).

The vast majority of research on organizational signalling tends to investigate the ways in which a positive signal – in isolation – influences the decision-making of external constituents (Connelly et al., 2011; Stern et al., 2014). Here, the assumptions that underpin signalling theory – namely, that signals are noticed and/or attended to by almost everyone and that individuals respond in ways that correspond to the valance of a given signal – imply high rationality (Kim and Jensen, 2014; Park and Patel, 2015; Pollock and Gulati, 2007). As a result, research on organizational signalling offers little insight into how and why signals are attended to and how multiple (often competing) signals are interpreted. Because cognitively processing multiple, often conflicting, signals is both complex and challenging, we presently lack robust theory explaining how such signals are interpreted by the receiver. These considerations highlight the need for a rich, theoretically consistent cognitive foundation for better understanding how decision-makers process multiple organizational signals.

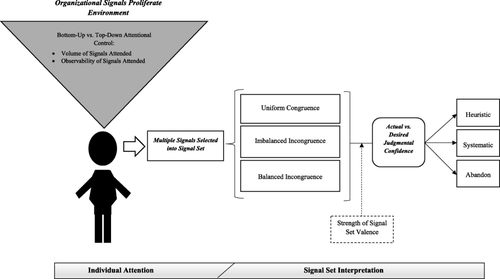

In this paper, we take a step in this direction by introducing a new theory and associated propositions to investigate the attention individuals pay to and their interpretations of multiple signals. Adopting a dual process explanation (Jonas et al., 1997; Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991; Sengupta and Johar, 2002), we theorize about the cognitive mechanisms individuals employ as they allocate attention to organizational signals, exploring why certain types of signals may differentially capture attention. Here, we explore how attentional control influences both the volume and types of signals individuals attend to. As multiple signals become available for further processing, we introduce the concept of signal sets and in turn identify three forms of signal sets that decision-makers can encounter in their organizational assessments: uniform congruence, imbalanced incongruence, and balanced incongruence. We then shift focus to individuals’ interpretation of these signal sets, drawing again on the dual process explanation for judgements and decisions to explore the key mechanisms (e.g., judgemental confidence) underlying the cognitive processes associated with the various signal sets.

Our cognitive approach to delineating the dynamics of signal attention and interpretation arises from the need to better understand multi-signal environments and makes several contributions to the literature. First, management scholars are increasingly relying on Spence's (1973) articulation of signalling theory to explain phenomena like stakeholder decisions and behaviours. While clearly useful, signalling theory's future applicability to areas that management scholars study is limited because of the aforementioned focus on the ways in which a lone signal in isolation (Bergh et al., 2014; Kim and Jensen, 2014; Park and Patel, 2015) or the unidirectional congruence of multiple signals (e.g., Pollock et al., 2010; Stern et al., 2014) influences the decision-making of external constituents. As management researchers move to explore increasingly complex environments where multiple signals with competing valence (positive and negative signals) are the norm, it becomes problematic because signalling theory research, as formulated by Spence and those who followed, does not adequately explain how individuals allocate attention to or interpret multiple signals. It is particularly silent on what happens when multiple signals are of competing valence. We address this gap via new conceptualizations regarding how and why individuals uniquely attend to certain organizational signals from the many signals available and introduce the cognitive mechanisms that set the stage for their mental processing of multiple signals.

This leads to our second contribution: the application of the heuristic-systematic model as a dual process framework that underpins attention to organizational signals. Challenging the assumption that signals are noticed equally by everyone, our theory accounts for the role of different modes of cognitive processing and the ways variations in attentional control (i.e., bottom up, top down) influence both the volume and nature of signals individuals attend to. Doing so adds depth to our understanding of this oft-neglected stage that precedes signal interpretation and lays the groundwork for our third contribution. Here, we explore individuals’ interpretation of multiple organizational signals as they flow into what we introduce as signal sets. The application of the heuristic-systematic model generates new insights regarding what happens cognitively when a decision-maker faces multiple signals that are in some cases congruent, but more importantly, our approach addresses those situations in which signals are incongruent – a context individuals in the field commonly experience.

In sum, addressing signal attention and interpretation within multi-signal environments, we advance a cognitive perspective that has the potential to energize future conceptual and empirical research across a range of disciplines. The outcome is a new understanding not only in the specific context of organizations and management but also in the broader domain of signalling theory such that the tradition of Spence's original formulation is extended through a cognitive lens.

SIGNALLING THEORY AND ORGANIZATIONAL EVALUATIONS

Signalling theory focuses on communication among actors in the midst of information asymmetries (Spence, 1973). Under these conditions, decision-makers rely on signals thought to covary with underlying, often unobservable, attributes. Concretely, in his seminal work on signalling, Spence (1974, p. 1) refers to signals as ‘activities or attributes of individuals in a market which, by design or accident, alter the beliefs of, or convey information to, other individuals in the market’. Signals, then, serve to reduce information gaps or asymmetries between two parties (i.e., the audience receiving the signals and the signal sender). A key aspect of this approach is that an effective signal sets focal objects apart from the sample in terms of quality, leading to a separating equilibrium (Bergh et al., 2014; Spence, 1973). For example, in labour markets, education credentials originally served as a signal of an individuals’ underlying potential as a job applicant, separating higher-quality applicants from their lower-quality counterparts (see Spence, 1974).

As signalling theory has been applied to the organizational realm, the perspective has provided many rich insights, emerging as a mainstream theory in organizational studies (see Allison et al., 2013; Busenitz et al., 2005; Certo, 2003; Jones et al., 2014; Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009; Nam et al., 2014; Park and Patel, 2015; Plummer et al., 2016; Reuer et al., 2012; Stuart et al., 1999). Specifically, because of the high levels of uncertainty and information asymmetry surrounding organizations (particularly emerging growth ventures), scholars have applied signalling theory logic to advance the idea that signals can be used as a mechanism for differentiating firms’ quality. This approach has proven useful as actors outside organizations rely on various signals to make inferences about underlying and difficult-to-observe characteristics of organizations and their offerings (Certo, 2003; Etzion and Pe'er, 2014; Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009; Rao et al., 1999; Stuart et al., 1999). As such, the application of signalling theory has proven to be useful in advancing our understanding of where organizational signals originate, what specific signals flow from those sources, and what resultant impact those signals have on decision-makers outside the organization.

Persisting Gaps: Cognitive Processing of Multiple Signals

While much has been learned about the sources of organizational signals and the specific signals sent, the signalling literature has limited explanatory power because investigations to date are regularly predicated on a rational foundation that assumes near-unanimous attention and reactions to either isolated or congruent signals (Bergh et al., 2014; Kim and Jensen, 2014; Park and Patel, 2015; Pollock and Gulati, 2007). A scan of the contexts commonly studied in the organizational signalling environment, though, reveals environments proliferated by vast numbers of signals available to the decision-maker. In such contexts, individuals realistically rely on a smaller subset of these signals and often must make sense of multiple signals that compete with one another. This realization is phenomenologically perplexing because the rational predictions typically employed by signalling scholars break down, offering minimal insights regarding how individuals attend and respond to the simultaneous occurrence of multiple, frequently incongruent, signals. Thus, we advance that a plausible reason signalling theory research has yet to account for environments proliferated by vast numbers of signals with competing valence is that such dynamics are not visible via the theoretical perspectives used to date. Put differently, attending to and interpreting multiple signals that often conflict are cognitively difficult tasks, and we presently lack strong theory that effectively explains these key processes. Hence, what seems to be critically important in signalling theory – but is often overlooked in current formulations – are the cognitive considerations of the decision-makers, or signal receivers.

Our investigation begins to fill this void by pushing signalling research beyond rational responses to a positive signal in isolation (e.g., Stuart et al., 1999), or in unidirectional congruence (e.g., Pollock et al., 2010; Stern et al., 2014), to instead conceptualize individuals’ allocation of attention to and subsequent interpretation of simultaneous positive and negative signals. To that end, we offer a theory grounded in the tenets of the signalling literature but developed using insights derived from cognitive science. Adopting a dual process perspective, we explore the cognitive dynamics of organizational evaluations made by external decision-makers, theorizing about signal attention and subsequent multi-signal interpretations of signal sets. Doing so, we begin by offering an overview of the relevant cognitive science literature and the dual process perspective before discussing their application to organizational signalling dynamics.

COGNITIVE PROCESSING OF MULTIPLE SIGNALS: A DUAL PROCESS APPROACH

Modern cognitive science research dates to the 1950s, and since that time, much attention has been devoted to unearthing the various cognitive processes underpinning human judgements and decisions. As a result, many theories and models have been introduced, including, for example, pattern recognition (Reed, 1972), mental model formation (Johnson-Laird, 1983), and creative thought (Ward et al., 1997). However, these models have limited explanatory power in complex decision environments because they assume the use of a singular cognitive process; hence, there are decision dynamics that fall outside the scope of these frameworks (Hastie, 2001). This lack of explanatory power has led to the emergence of a complementary line of theories that take a dual process perspective.

The dual process approach advances that the mind processes information via two distinct modes. The first mode operates automatically by triggering memory-based cognitive processes of association, whereas the second mode requires greater conscious effort and involves deeper and more systematic processing (Chen and Chaiken, 1999; Dane and Pratt, 2007; Evans, 2008; Healey et al., 2015; Smith and DeCoster, 2000). An important advantage of the dual process approach is that developed frameworks are better equipped to deal with complex situations, such as the signalling environment, because they do not assume that a single cognitive process operates across the board. Instead, dual process models advance that people utilize either associative or systematic processes, where their use varies as a function of information content, contextual demands, individual differences, and so on (Smith and DeCoster, 2000). Importantly, the dual process perspective has gained prominence in management research, with scholars advancing dual process models of executive and entrepreneur decision-making (see Elsbach and Kramer, 2003; Wood and Williams, 2014).

Despite these advances, the literature to date has not yet applied the dual process approach to signalling theory. We do so here because, as the discussions above highlight, the dual process approach has proven to be a useful and flexible framework for complex decision environments. However, it should be noted that there are many variants of the dual process perspective. Starting with Chaiken's (1980) work on heuristic versus systematic processes, on to Gilbert's (1989) focus on inference versus attributional thinking, and finally to Sloman's (1996) conceptualization of associative versus rule-based thinking, we find a rich diversity of dual process theories that could potentially be utilized. However, we are most closely inspired by a theory called the heuristic-systematic model (HSM). HSM posits that people make judgements and decisions using low-effort decision rules, but if that approach is insufficient, they may switch modes to employ more effortful systematic mental processes (see Chen and Chaiken, 1999; Ferran and Watts, 2008). HSM is notable in that it builds on the aforementioned foundational dual process theories but goes further by accounting for the realization that certain variables ‘can trigger qualitatively different information processing’ (Todorov et al., 2002, p. 195). While HSM does not refer to signals or signal processing specifically, it is germane in this context because it can ultimately aid in explaining how different types of cognitive processing (heuristic versus systematic) influence both the initial attention individuals pay to organizational signals and their subsequent interpretation thereof.

Heuristic-Systematic Model: An Overview

HSM is a dual process framework centred on decision dynamics in ambiguous situations in which individuals are focused on accuracy and seek validity (Aydinoğlu and Krishna, 2011; Chen and Chaiken, 1999). Here, decision-makers are assumed to be motivated by the desire to attain views that are accurate and supported by facts (Ferran and Watts, 2008; Jain and Maheswaran, 2000). A unique aspect of HSM is that the framework focuses on the decision-maker's desired level of judgemental confidence, conceptualized as the degree of confidence one desires to have in his or her knowledge as it relates to satisfying processing goals (Griffin et al., 2004).1 Judgemental confidence is subjective and varies between individuals but is thought to be stable within individuals as it relates to a specific judgement target. In that way, desired judgemental confidence in one's knowledge and understanding about the target represent a decision threshold that must be crossed. As such, HSM's focus on judgemental confidence provides a fundamental advantage over other dual process theories because actual versus desired judgemental confidence is a concrete and measurable cognitive mechanism that activates different legs of dual cognitive processing, thereby affecting how decisions are ultimately made (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Ferran and Watts, 2008).

The overarching logic of HSM is that individuals form varying levels of judgemental confidence once their mental attention is brought to bear on evaluating an object (Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991). This reasoning naturally implies that decision-makers are motivated to attain a ‘sufficient’ level of judgemental confidence in their evaluations – namely, the desired level of judgemental confidence they need to make a decision. The idea is that, facing any type of evaluation, all individuals form a desired confidence level regarding the target knowledge they require to move forward with the decision. Thus, one's internal comparison of his or her actual versus desired level of judgemental confidence determines the mode(s) of cognitive processing that person will rely upon (Chen and Chaiken, 1999; Ferran and Watts, 2008; Jain and Maheswaran, 2000). When a decision-maker initially realizes a sufficient amount of judgemental confidence via faster heuristic processing, HSM predicts that the decision will be made on the basis of this mode of processing alone given that decision-makers have no reason to invest more cognitive energy through further systematic assessment (i.e., akin to satisficing). Thus, individuals predominantly rely upon heuristic processing in evaluations when this mode of processing ultimately produces a level of actual judgemental confidence that exceeds the level desired.

When heuristic processing leaves one with an insufficient level of judgemental confidence – situations in which actual confidence is lower than the individual's desired level – systematic processing is then activated to ramp up cognitive processing to raise actual judgemental confidence to a sufficient level. In this way, the greater the (negative) gap between actual and desired confidence, the greater the likelihood systematic processing will be engaged (Todorov et al., 2002). When the desired level of judgemental confidence is reached through systematic processing, the decision-maker is likely to move forward with the decision at hand (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993, p. 330). As such, HSM offers a unique conceptual framework for understanding the cognitive mechanisms at play as individuals process information related to a decision target (Ferran and Watts, 2008; Jonas et al., 1997; Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991).

However, before judgemental confidence can be evoked in the decision process, one must first attend to information perceived to be relevant to the target. That is, for signals to be interpreted via the mechanism of desired versus actual judgemental confidence, they must first be drawn into the decision-maker's field of attention (Eysenck et al., 2007; Posner, 1980; Parasuraman, 1998). As such, we first apply insights from psychology research to shed new light on how people are likely to attend to individual signals within the dual process framework. We then explain how individuals interpret these signals, focusing on how the mechanisms underlying judgemental confidence come into play to determine which leg of HSM processing is engaged.

Attending to Individual Signals

The first stage in our model addresses the cognitive dynamics of signal attention, explaining how and why individuals attend to some but not other signals. This approach necessitates grappling with attention and attentional control as they relate to organizational signals. Attention is of concern because it is well-documented that people are bounded by rationality (Simon, 1991) such that individuals can rarely, if ever, attend to all available data when making judgements and decisions (Hahn et al., 2014; Hastie, 2001; McMullen et al., 2009; Ocasio, 2011; Shepherd et al., 2017). Instead, individuals usually consider only a subset of available information, making evaluations based on selective attention (Jonas et al., 2001; March and Simon, 1958; Ocasio, 2011; Simon, 1955; Walsh, 1988). This dynamic has been heavily studied, with research on the nature of consciousness and volition documenting the importance of the concept of attention, defined as the allocation of limited cognitive processing capacity toward selective concentration on particular information (Derryberry and Reed, 2002; Fox et al., 2002). In other words, cognitive processes of attention involve being cognizant of changes, trends, and events in the environment and focusing on a subset of these.

Cognitive science research states that shifts in attention are largely a function of either top-down goal-driven or bottom-up stimulus-driven processes (Eysenck et al., 2007; Posner, 1980; Shepherd et al., 2017; Parasuraman, 1998). Top-down processes flow endogenously from having a goal in mind, with individuals utilizing HSM's systematic processing to engage in effortful search and selection of information thought to be relevant to achieving that goal. The bottom-up approach rests on the exogenous introduction of a stimulus and engages HSM's less effortful and more automatic heuristic processing in response to information that triggers a latent cognition (Corbetta and Shulman, 2002). A key difference, then, between bottom-up and top-down attentional control is the presence of an external stimulus: in bottom-up processing, an external stimulus is required, whereas in top-down processing, it is not. This is because top-down attentional control is endogenous and non-automatic (i.e., rests on systematic processing), while bottom-up attentional control is exogenous and automatic (i.e., rests on heuristic processing) and thus necessitates an external stimulus noticeable enough to automatically shift one's attention (Pashler et al., 2001).

Taken together, these insights are relevant for advancing signalling theory because they speak to the ways decision-makers’ attention might be drawn to certain organizational signals. Specifically, as the discussions above make clear, individuals can attend to only a subset of all available signals that pertain to an organization, but signalling scholars have 1) tended to ignore this reality, and 2) failed to consider there may be variations in the volume of signals that receive one's attention. In this vein, the cognitive science research on attentional control just discussed suggests that individuals will attend to signals via either top-down systematic processing or bottom-up heuristic processing. We contend that these processes differentially affect the number and types of signals attended to and thus available for subsequent interpretation within the set of signals one uses to make an evaluation.

Organizational signals: Top-down versus bottom-up attentional control

In top-down attentional control, individuals attend to information because of an endogenously generated goal. If, for example, an individual sets out to buy a new car, the presence of that goal stimulates an active search for information related to purchasing a new a car. The individual may search for information on an automobile manufacturer in quality reports when just days before he or she may have ignored such information. What this example illustrates is that for top-down processing, a goal is ‘necessary for an endogenous attention shift, but no particular stimulus event is necessary’ (Pashler et al., 2001, p. 631); this means that one's attention field (and thus the possible data considered) is likely to become wider, largely driven by the goal at hand and corresponding active search.

This contrasts with bottom-up attentional control. In this process, attention is reflexive in the sense that one is reacting to a piece of information that captures his or her attention without consideration of relevance to a goal. Returning to the prospective car buyer, a national news report on a manufacturer's global recall may capture his or her attention toward that manufacturer even though attaining such information had not been intentional. Indeed, it is the appearance of information about something new (Yantis and Hillstrom, 1994), about changes to something established (Yantis and Jonides, 1984), or about discontinuities in immediate neighbours’ properties (Wolfe, 1992) that often serve as stimuli triggering bottom-up heuristic-type processing. This is because information along these lines stands out in a way that attracts attention reflexively (Pashler et al., 2001). Given the passive nature of reflexive attention, the focus of attention tends to be narrowly centred on the stimuli in light of present understanding that creates a backdrop for noticeable change.

Applied to the realm of organizational signalling, this reasoning suggests that we would expect to see measurable differences in the number of organizational signals individuals attend to when evaluating an organization. When an individual has developed a goal related to an organization, top-down systematic processing is evoked, and the decision-maker is likely to attend to as many signals as possible. This increased attention is because signal attention is volitionally driven by the goal of evaluating the organization, which in turn stimulates active search for additional signals and openness toward noticing additional signals that might inform the decision. Individual attention, though, differs from what unfolds when one has not developed a goal related to an organization but notices a signal communicated by an organization because it stands out in some way. When this happens, bottom-up processes are stimulated, and because it is the signal that passively stimulated thinking about the organization, attention is largely confined to signals related to the trigger. There is no goal related to the organization to drive the individual to seek additional signals like in top-down systematic attentional processes, so the volume of signals that draw attention is likely constrained.

Proposition 1: Attentional control influences the number of signals individuals attend to such that individuals operating with top-down systematic processing will attend to more organizational signals than those operating with bottom-up heuristic processing.

Signal observability and attentional control

Further untangling how decision-makers cognitively attend to organizational signals, we consider the role of a key signalling assumption: signal observability. Signal observability can be defined as ‘the extent to which outsiders are able to notice a signal’ and reflects the degree to which a signal is easily attended to by an organizational outsider (Connelly et al., 2011, p. 45). Here, the underlying assumption is that signals must be observable to draw attention, but they can vary along a continuum of observability: high-observability signals are easily noticed because the information is more visible to the decision-maker (e.g., highly publicized actions of a famous CEO). By contrast, low-observability signals are more hidden to the decision-maker because such signals are simply less visible. Signal observability is relevant to our model because we reason that an individual's cognitive processes – bottom-up or top-down attentional processing – can shed new light on why certain types of signals may or may not receive selective attention.

When it comes to highly observable signals, they are readily visible and have a high chance of standing out to perceivers regardless of the processing mode engaged. When an organization is being evaluated as a possible acquisition target in the merger and acquisition setting, for instance, the company's highly publicized sales momentum is a signal outside observers are likely to notice – again, regardless of processing mode. In contrast, low-observability signals involve information that is less visible, making them less likely to be equally noticed across modes of processing. With regard to bottom-up processing, it becomes less likely that low-observability signals will be noticed given the increased cognitive effort required to uncover such signals. In this way, we reason that those operating with bottom-up processing are likely to tend to high-observability signals but not low-observability signals. Top-down systematic processing, alternatively, increases the likelihood that low-observability signals will be considered. Because top-down attentional processes rest on goal-driven active search, those engaged in this type of cognitive processing will be more likely to seek out signals beyond those that are easily visible. Thus, when signal observability is low, such signals are more likely to be discovered by those operating with top-down systematic processing given the heightened cognitive effort.

Proposition 2: Attentional control influences the number of low-observability signals individuals attend to such that individuals operating with bottom-up processing will attend to fewer low-observability signals than individuals operating with top-down processing.

Signal Sets

To this point, we have focused on the cognitive processes associated with attending to individual signals. While this is an important piece of the puzzle, it leaves open the question of what unfolds after signals enter one's attentional field. We now address this question by further drawing on heuristic and systematic processing, but we do so with a focus on the key HSM tenet of judgemental confidence (Griffin et al., 2004) and a comparison between one's desired and actual level of judgemental confidence as a key mechanism in multi-signal interpretation. Notably, judgemental confidence forms during signal interpretation rather than the attention stage. During the attention stage, the individual simply becomes cognizant of signals available for possible further consideration, but these signals are not processed at a deeper level. During interpretation, the individual's level of confidence in his or her knowledge about the organization forms based on the signals he or she attended to. Such reasoning is consistent with cognitive neuroscience research documenting that different parts of the brain are activated during attention (prefrontal and parietal regions) than for deeper-level dual process judgement activities (hippocampus and the perirhinal cortex) (Rugg and Yonelinas, 2003; Sarter et al., 2001).

In this vein, we argue that once individual organizational signals become the focus of an individual's attention either through top-down or bottom-up attentional control, those signals are available for selection into that person's signal set – what we define as the collection of signals used for interpretation. The idea here is that a person gathers multiple signals individually, and his or her interpretation then hinges on the number and valence of the multiple signals in his or her signal set. We advance that signal sets produce signal set valence, which is defined as the collective valence – positive, negative, or varying degrees of both – that results as signals are selected into a definitive set. What dictates signal set valence is the collective volume and strength of the selected organizational signals and their assigned weight. Taking the combined positive and/or negative valences of each individual signal within a set produces the resultant signal set valence. Signal sets can take one of three possible forms, or valence configurations, in the mind of decision-makers. We illustrate each of these configurations in Table 1 and then describe them in turn.

| Uniform congruence | Imbalanced incongruence | Balanced incongruence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example Set 1: | + + + + | ||

|

Example Set 2: Example Set 3: Example Set 4: |

− − − − |

+ − − − + + + − |

|

|

Example Set 5: Example Set 6: |

− − + + + + − − |

The first configuration is where the signal set valence is uniformly positive or negative, giving rise to a situation we label uniform congruence. This context is the focus of the clear majority of extant signalling research and exists when signals unanimously communicate the same message regarding positive or negative organizational quality. The second potential configuration – imbalanced incongruence – exists when a signal set comprises both positive and negative signals, and the signal set valence is such that it is positively or negatively skewed in the mind of the decision-maker. In the case of imbalanced incongruence, signal sets simultaneously include positive and negative valences, but one direction dominates. The third and final configuration entails a signal set comprising an equal valence of positive and negative signals. We characterize this situation as one of balanced incongruence, for which the valence of the signals selected into the set is such that positive and negative signals communicate equally competing valences.

Together, signal set valence captures the ubiquitously studied uniform congruence but also reaches beyond to consider incongruent signal sets as either imbalanced or balanced (as illustrated in Table 1). Addressing the latter two instances highlights the insufficiency of current conceptual models used to explain signalling activity as the predictions/responses developed within the dominant uniform congruence paradigm address only a subset of possible signal configurations. These conceptualizations provide the basis for our theorizing that follows.

Uniform congruence

Prior research suggests that when faced with congruent information signals, decision-makers are more apt to rely on heuristic processing because they have little reason to engage in further systematic processing (e.g., all positive in uniform congruence) (Jonas et al., 1997; Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991). As Jonas et al. (1997, p. 193) note, ‘[W]hen individuals are faced with objects that have evaluatively consistent attributes, systematic processing should not be necessary for attaining sufficient judgemental confidence. A superficial examination of the object's properties may instead lead to heuristic-based impression such as ‘this product has only advantages’. However, in such instances, simply because there is unanimous congruence does not always mean that individuals solely rely on heuristic processing when making decision.

Proposition 3a: When individuals face uniform congruence, stronger signal set valence increases the likelihood that they will cross their desired judgemental confidence threshold.

Proposition 3b: When individuals face uniform congruence, stronger signal set valence increases the likelihood that they will predominantly rely on heuristic processing.

While Proposition 3 advances our understanding of congruent signals, we acknowledge that in many instances, decision-makers do not consider unidirectional signals within their signal set. The introduction of competing signals and valence gives rise to situations in which individuals interpret multiple pieces of competing information. Here, extant cognitive science research asserts that the magnitude of simultaneous competing beliefs about a focal object dictates the individual's level of ambivalence (Kaplan, 1972; Piderit, 2000; Plambeck and Weber, 2010; van Harreveld et al., 2009). Specifically, one experiences higher levels of ambivalence when he or she views an attitude object as increasingly positive and negative at the same time, resulting in an uncomfortable negative state (Jonas et al., 1997; Nordgren et al., 2006). HSM is particularly germane to multiple signal reception given that information inconsistencies can play an important role in determining one's mode of cognitive processing (Jonas et al., 1997; Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991; Nordgren et al., 2006). Prior research suggests that information inconsistencies often encourage decision-makers to evaluate the information set more extensively, ultimately reconciling contradictory information when forming an integrated evaluation (Chen and Chaiken, 1999; Jonas et al., 1997; Sengupta and Johar, 2002). In light of this, we next theorize about incongruent signal interpretation in the form of imbalanced and balanced signal sets.

Imbalanced incongruence

Proposition 4a: When individuals face imbalanced incongruence, the greater the positive-negative valence gap within their signal set, the greater the likelihood they will cross their desired judgemental confidence threshold.

Proposition 4b: When individuals face imbalanced incongruence, the greater the positive-negative valence gap within their signal set, the greater the likelihood they will predominantly rely on heuristic processing.

Balanced incongruence

Proposition 5a: When individuals face balanced incongruence in a weak form, they cannot reach their desired judgemental confidence threshold via heuristic processing, triggering reliance on systematic processing.

Proposition 5b: When individuals face balanced incongruence in a strong form, desired judgemental confidence is perceived as unattainable with reasonable cognitive effort, and there is a greater likelihood of at least temporary abandonment of systematic cognitive processing.

Taken together, our propositions represent a model of individual attention and signal set interpretation. We illustrate the core elements of our theorizing and how they relate in Figure 1.

A model of individual attention and signal set interpretation

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of our conceptualizations is to provide an improved paradigm for understanding how individuals attend to and subsequently interpret multiple organizational signals. Our application of the HSM dual process approach contributes to the literature on signalling theory (Spence, 1973) and the management scholarship utilizing the signalling lens (see Connelly et al., 2011) by addressing the tensions that arise from significant conceptual gaps in the signalling perspective. Specifically, the principal limitation with current formulations and applications of signalling theory is an underlying and often-overlooked incompleteness problem (Locke and Golden-Biddle, 1997) that has arisen because the literature lacks theoretical specification around the complex cognitive processes associated with allocating attention to and interpreting multiple signals. This is especially true when it comes to considering multiple incongruent signals that commonly flow from organizations as the literature has been mostly silent on these dynamics. To that end, our theory contributes to signalling theory by offering a first step toward cognitive-driven insights that explain how individuals attend to and interpret multiple organizational signals. These efforts yield several interrelated benefits for future organizational research employing signalling theory, and we highlight them in turn.

Advantages of a Cognitive Dual Process Approach

In Spence's original formulation of signalling theory, the objective was to explain how information asymmetries could be reduced between two parties via signals (Spence, 1974, 2002). Applied to management and entrepreneurship, the notion of signalling to reduce information asymmetry has been useful but largely addresses how organizations signal quality to those outside their boundaries via avenues like board characteristics (Certo, 2003) and founder/top management team characteristics (Lester et al., 2006). This approach says very little about the signal receiver – how and why he or she might attend to signals and what transpires when multiple signals are considered concomitantly. In this way, the literature on organizational signals is incomplete because it treats the cognitions of the receiver as a ‘black box’. This makes sense given that theorists have essentially viewed signal receivers as mindless automatons who are assumed to all attend and react to organizational signals once available and do so relying on either single or congruent signals.

This approach, however, is based on unfounded/flawed assumptions given we know that decision-makers are bounded by rationality (March, 1994) and cannot attend to all available signals (Shepherd et al., 2017). Moreover, while several signals may receive attention, as those signals flow into one's signal set, there are long odds that all the signals in the set will be exclusively positive or negative (as traditionally approached). Therefore, we contend that the research to date is based on assumptions that lack ecological validity (Schmuckler, 2001) because they do not fully reflect real-world phenomena. Our theory responds to these issues by repositioning the current conversation to bring into focus the complex and cognitively challenging process of attending to and processing multiple, possibly conflicting, signals. Our approach not only highlights the latent potential of integrating a cognitive perspective in a general sense but also offers a platform for future empirical testing of signal reception that accounts for the mental processes of individual signal receivers.

More specifically, our introduction of HSM as a dual process perspective breaks new ground as different parts of the landscape come into view. First, the question of how and why signal receivers differentially attend to some signals while ignoring others becomes a key consideration. Because the literature tends to overlook this dynamic, we introduced a dual process approach that accounts for the top-down systematic and bottom-up heuristic processes individuals use to attend to organizational signals; the process actually used then has differential implications for the number of signals considered. This adds to current understandings because it explains why some decision-makers may act passively, therein considering only a few signals, while others may actively search for signals and therefore become aware of a broader number of signals. This theorizing represents a meaningful step forward because it addresses ongoing scholarly conversations that have neglected the realization that individuals vary in terms of the volume of signals they use to make organizational assessments. Such realizations also shed further light on the role of signal observability, for example, by offering a cognitive explanation for the conditions under which less-visible signals prove influential. Despite notions assuming that high signal visibility is necessary for a signal to be effective (Connelly et al., 2011; Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009), we paint a more nuanced picture that offers insights into the cognitive processes associated with attention to signals that are both higher and lower in observability. Future empirical research can further tease out the contingent role of signal observability as a function of individual-level cognition.

Beyond the realm of signal attention, our theory has important implications for researchers seeking to explain phenomena related to what happens once signals receive attention and are selected into a signal set for interpretation. The delineation of various forms of signal sets is a novel advancement, and the idea that signal sets activate different types of HSM processing is impactful because it accounts for the cognitive effort problem. That is, prior research assumes that signal receivers will give full cognitive attention and effort to discerning the meaning of organizational signals and thus fails to account for passive versus active signal interpretation. While there are several stumbling blocks with this approach, principal among these barriers is that we know individuals who use heuristic processing frequently make different decisions than those who use systematic processing. Contingent upon signal sets, our study lays the foundation required to explore differences in decision outcomes as a function of the HSM processes utilized. This work moves the conversation around organizational signals forward by adding a conceptual framework explaining how individuals cognitively interpret multiple signals, thus enabling theorists to now model effects and predict relationships between signal sets and resultant outcomes. We believe this is an important contribution to the literature that opens the door for lines of empirical inquiry capturing responses to various configurations of congruent and incongruent signals.

Simultaneous versus Sequential Interpretation

To date, signals have largely been modelled in an isolated fashion. Our conceptualizations move the literature toward capturing the simultaneous interactions of multiple signals. By highlighting the more complex but arguably more phenomenologically accurate joint consideration of both positive and negative signals, scholars have the potential to re-energize signalling theory research as we begin incorporating the interactive nature of multiple signals of competing valence into future research investigations.

A boundary condition of our framework is that it does not address time, or temporal considerations. Most conceptual and empirical studies of organizational signals employ linear models that are presumed to occur at single point in time (Etzion and Pe'er, 2014; Janney and Folta, 2006). By studying signal attention and interpretation as a temporal process, future inquiry can offer a perspective that is under-represented in management research but essential to understanding the transformative process by which multiple signals are used by organizational outsiders. While our reasoning points to this possibility and provides a framework for investigating it, researchers will need to conceptually and empirically explore differences between the processing of simultaneous versus sequential signal attention and interpretation. For instance, if we hold the signals constant, does one make different decisions if signals are added to the signal set in a simultaneous versus sequential fashion? As such, exploring the reception of multiple signals over time as they enter an individual's attention field and subsequently become part of his or her signal set represents an important frontier for signalling research in management studies. This need is particularly strong given that the occurrence and consideration of multiple signals – in varying configurations unfolding over varying temporal distances – likely represents the norm rather than the exception in the field.

Methodological Implications

While our contribution is the introduction of an HSM conceptual approach to organizational signalling, our theory has some important methodological implications. Specifically, the overwhelming majority of signalling research within the organizational domain relies on the analysis of secondary data. While clearly offering advantages (i.e., generalizability), such an approach is also associated with downsides that have fuelled the broader neglect of organizational signal attention and interpretation by external evaluators. HSM shifts the focus to the receiver and his or her cognitions and judgements, which do not lend themselves well to investigations via secondary data. Rather, approaching signalling from the perspective of the receiver's use of heuristic and systematic cognitive processes likely requires a different set of methodological tools. In that vein, we advance that the use of experimental and qualitative techniques can serve as a profitable path forward.

First, deploying experimental methods has advanced many important areas of inquiry, such as entrepreneurial opportunity recognition (see Haynie et al., 2009; Shepherd et al., 2015; Short et al., 2010), strategic decision-making (see Korsgaard et al., 1995; Mitchell et al., 2011), investor cognition (Drover et al., 2017; Murnieks et al., 2011), and the like. We suspect such tools can do the same for the signalling dynamics articulated in our conceptualizations. The key advantage is that experiments using signal receivers as subjects allow for controlled analyses pertaining to signal attention and interpretation, such as how and when signals are generated and how and when they are attended to by decision-makers, as well as the interactive nature of multiple congruent and incongruent signals (signal sets). Experimental techniques can be used to design theory-driven signals to stimulate differences across individual decision-makers in a controlled setting. Conjoint analysis, for example, represents an experimental technique whereby the researcher can isolate, manipulate, and in turn quantify the effects of variation in multiple attributes (signals in this case) (Mitchell et al., 2011; Murnieks et al., 2011; Shepherd et al., 2013; Wood and Williams, 2014). Other approaches, such as rich scenario experiments (Grégoire and Shepherd, 2012), provide viable vehicles to begin answering questions that pertain to the cognitive dynamics of signal attention and interpretation.

In a related vein, deploying qualitative methods (e.g., Autio et al., 2011; Bluhm et al., 2011; Mathias and Williams, 2017) also represents a potentially useful avenue to study organizational signalling in new ways. Interpretive qualitative approaches allow for a deep dive into the mind of the signal receiver, yielding new understandings of the ways signals are selected and processed. This approach may provide new insights into the cognitive mechanisms that lead individuals to attend to particular signals while ignoring others. Using signal receivers as subjects, qualitative techniques, such as grounded theory (Bluhm et al., 2011; Shepherd and Williams, 2014), can help tap into the individual selection of signals and the interlinked cognitive processes associated with organizational signal reception and the processing and judgements that follow.

Collectively, given the narrow use of empirical approaches traditionally used by organizational signalling scholars, broadening the scope of our methodological toolbox can bolster our understanding of signalling theory in ways that are profound.

Extensions to Other Areas

Our focus has primarily centred on the evaluation of organizations by, for example, prospective consumers, financers, and merger and acquisition stakeholders. The applicability of signalling theory and our cognitive-driven extensions, though, can also extend to other areas of inquiry. In this way, another area of research where the ideas advanced in our paper may provide insights is within organizations. For instance, how does our model help inform the interacting attributes of individual assessments, such as evaluations of one's leader? Here, researchers might explore how signals generated by leaders impact follower judgements and key outcomes, such as retention. To the best of our knowledge, researchers have yet to investigate the degree to which multiple conflicting signals are generated about leader competence, for instance, so we presently know little about how the dual process approach we employed might operate in this type of context. Our approach may assist in informing what type of information individuals notice and how interacting (and often competing) data points are cognitively processed. Moreover, the study of legitimacy has long been an important issue, and the dynamics described in this literature closely parallel the idea of signalling (e.g., Haack et al., 2014; McKinley et al., 2000; Suchman, 1995; Zimmerman and Zeitz, 2002). What transpires when multiple attributes or actions are simultaneously perceived as legitimate and illegitimate? How are overall perceptions of legitimacy shaped in the face of conflicting indicators of (il)legitimacy? These are the types of questions that may potentially be addressed in light of our framework, which aids in explaining cognitive responses to signal sets.

The broader point is that the cognitive approach we advance has the potential to inform responses across a wide range of important organizational decision contexts where information asymmetries are the norm. Our framework provides a platform for investigations along these lines, representing a substantive improvement over approaches to date given their inability to address such phenomena.

CONCLUSION

The communication of signals is vital in the organizational domain. Recognizing this importance, researchers have made considerable progress to further our understanding of organizational signalling (Busenitz et al., 2005; Certo, 2003; Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009; Nam et al., 2014; Ozmel et al., 2013; Plummer et al., 2016; Stuart et al., 1999). By extending this work to the signal receiver and conceptualizing the cognitive processes associated with signal attention and signal set interpretation, we move the literature forward in important ways. Together, we hope that our study encourages scholarly pursuits that more comprehensively account for the cognitive complexities of signaling theory as applied to organizational dynamics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Editor Penny Dick and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that pushed us to improve the paper.