Why and How Do Employees Break and Bend Confidential Information Protection Rules?

ABSTRACT

Organizations cannot function effectively if their employees do not follow organizational rules and policies. In this paper, we explore why and how employees in two high-tech organizations often broke or bent rules designed to protect their employers' confidential information (CI). The CI protection rules sometimes imposed requirements that disrupted employees' work, forcing employees to choose between CI rule compliance and doing their work effectively and efficiently. Employees in these situations often broke the rules or bent them in ways that enabled employees to meet some of the rules' requirements, while also satisfying other expectations that they faced. We discuss implications of our findings for practice and for future organizational scholarship on rule following.

INTRODUCTION

In order to succeed, organizations must be able to direct the behaviour of their employees, and one of the most common means that organizations use to accomplish this objective is the implementation of rules (Scott, 1981). Rules, however, are only effective when employees actually comply with their requirements, and companies that cannot persuade employees to follow rules may struggle to survive and thrive (Ostroff and Schmitt, 1993; Tyler and Blader, 2005). The importance of ensuring employee compliance with rules is illustrated by the fact that most, if not all, organizations have systems that are designed to encourage rule following and to punish employees who break rules (Beck and Kieser, 2003; Hale and Borys, 2013; March et al., 2000; Tyler and Blader, 2005). Yet, in spite of the prevalence of these systems, rule breaking continues to be common in organizations (Hale and Borys, 2013; Healy and Iles, 2002; Robinson and Bennett, 1995).

One reason why employees do not follow organizational rules is because on occasion, the requirements of rules disrupt their work (Elling, 1991; Guo et al., 2011; Hale and Borys, 2013), meaning that employees cannot follow rules and get their work done efficiently and effectively. However, our review of the literature on rule following revealed that it stops short of developing a full understanding of how employees react in these situations. In particular, we know little about how and why employees in these circumstances choose to follow rules, to break them, or to find a way to reconcile the tension between the demands of the rules and the pressures of their other expectations.

To better understand why and how employees react when experiencing tension between rules and other workplace expectations, we examined rule following in the context of confidential information (CI) protection. This phenomenon is critically important to the effective functioning of many organizations (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000; Hannah, 2005; James et al., 2013; Liebeskind, 1997) and one in which rules are frequently broken, causing the leakage of valuable knowledge (McEvily et al., 2004) and costing companies billions of dollars in revenue (Hannah, 2006; Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2002; Shah and Stock, 2011). We also expected that this would be a context in which employees encounter rules that disrupt other aspects of their work. As one example, Apple Inc. goes to great lengths to ensure that employees comply with rules regarding the protection of CI (Diaz, 2009; Martellaro, 2010). However, top management has reportedly become so concerned about stopping information leaks that they have placed severe restrictions on employees' ability to take new products off the Apple ‘campus'. This in turn has made it difficult for Apple employees to field test new products, and a recent article cited employee concerns about now being unable to ‘test things to the level we want to test them before we ship' (Cheng, 2012). These Apple employees appear to be facing contradictory pressures: they are required to follow their employer's rules, but are also expected to ensure that products are thoroughly tested before they launch. In our research, we aimed to understand how employees facing similar circumstances would react. We began our inquiry with the following research questions: Why do employees follow or break CI protection rules? If they do not follow the rules, how do they break them?

To conduct our research, we adopted an inductive, qualitative approach designed to help us explore CI rule following from the perspective of employees. This approach enabled us to elaborate theory that is grounded in the perspectives and experiences of the employees making decisions about whether or not to break their employers' CI protection rules. We conducted 55 semi-structured interviews with employees in two high-tech companies. As the study progressed, we learned that CI rules were often interconnected with other workplace expectations faced by employees. In effect, the rules were ‘functionally linked or interdependent' (Lehman and Ramanujam, 2009, p. 651) with those expectations, often in ways that led to conflicting obligations and tension for employees. We uncovered three types of tensions that precipitated rule breaking: obstructions of work, disruptions of knowledge networks, and threats to employees' identities. We further learned how employees broke CI rules, sometimes totally ignoring all of their requirements, but at other times ‘bending' the rules by ignoring some of their requirements while obeying others. We build on these insights to elaborate new theory about how employees break rules. We posit that rule following and rule breaking may be best understood as ends of a continuum, where many forms of rule bending lie in between the two behaviours. Later, we discuss some of the opportunities and challenges that our findings imply for future organizational scholarship and for practice. Next, we review the literature that shaped our thinking and provided the theoretical context for our research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Rule Following in Organizations

Rules can be defined as ‘explicit or implicit norms, regulations, and expectations that regulate the behaviour of individuals and interactions among them' (March et al., p. 5). The question of why individuals do and do not obey rules has been explored in a number of disciplines, including psychology, criminology, and organization studies (MacLean, 2001). The discussion that follows draws together this limited and diverse research by reviewing what Tyler and Blader (2005) identified as the two key approaches to understanding rule following behaviour: the command-and-control approach, and the self-regulatory approach.

The command-and-control approach assumes an economic view of human behaviour: people attempt to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of their actions (Sutinen and Kuperan, 1999). This approach suggests that when employees decide whether to follow or to break rules, they will attend to the rewards and sanctions that are likely to result. Typically, the focus in this approach has been on sanctions, with the idea that if employees know they will be punished for rule breaking, they are less likely to do so (Hale and Borys, 2013; Kohn, 1999; Lehman and Ramanujam, 2009; Tyler and Blader, 2005). In theory, individuals will break rules up until the point where the marginal utility of rule breaking equals the likelihood and cost of the marginal penalty (Nagin, 1998; Sutinen and Kuperan, 1999).

The self-regulatory perspective on rule following, whose core ideas date back to Merton (1940), suggests that individuals may internalize rules so that they will choose to follow them independently of external sanctions (Tyler and Blader, 2005). In effect, this approach proposes that individuals may regulate their own conduct by choosing to follow rules regardless of potential rewards or punishments. Employees are more likely to do this when they perceive that the authorities who created the rules are legitimate (Tyler et al., 2007), that is, their actions are ‘desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions' (Suchman, 1995, p. 574). Within organizations, employees are more likely to comply with rules when they perceive that their personal values are congruent with their employers' values (Tyler and Blader, 2005), and with the rules themselves (Gezelius, 2004; Jenny et al., 2007; Sutinen et al., 1990). Tyler and Blader (2005) called this kind of rule following behaviour deference. While the command-and-control perspective focuses on ensuring employee compliance with rules, a self-regulatory perspective emphasizes the importance of employees' willing acceptance of the rules as an antecedent of deference.

Consequently, past research and theorizing suggests that employees will follow rules when incentivized to do so, and when they personally agree with and accept the rules. What is less known, however, is how employees react when rules come into conflict with one another, or with other activities in the workplace. To be clear, scholars have noted that rules can contradict one another, and that rule violations are more likely to result when contradictions occur (Elling, 1991; March et al., 2000). However, there is a great deal more to learn about the myriad of other ways in which rules can cause tension when they conflict with other workplace activities, and how the different types of tensions shape rule following behaviour. Next, we briefly describe the specifics of the phenomenon we studied in order to gain new insights into rule following: confidential information.

Confidential Information and Its Protection

In order to avoid leaking sensitive, valuable knowledge, firms commonly implement CI protection rules (Hannah, 2006). CI is defined as information that is not publicly available and that confers a competitive advantage to the organizations that possess it (Burshtein, 2000), and CI protection rules are designed to preserve that competitive advantage by (a) regulating who has access to the information and (b) restricting what individuals are permitted to do once they have access to it (Hannah, 2006). The value of CI is substantially determined by employees' ability to use the information in their work, for example by producing unique, inimitable products through secret formulae, or scrutinizing proprietary customer data to identify new markets for existing offerings. However, once CI is revealed to employees it is vulnerable, because any employee who knows CI may deliberately or inadvertently leak it to outsiders. If this results in competitors obtaining the CI, it can reduce a company's competitive advantage and benefit other firms (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000; Liebeskind, 1997).

Since there is clear evidence that CI protection is an extremely important issue for organizations, it is not surprising that a growing number of management scholars are interested in understanding how organizations can protect their CI effectively (Dufresne and Hoffstein, 2008; Hannah, 2007; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen and Puumalainen, 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Liebeskind, 1996; Stead and Cross, 2009). Much of the theorizing and research in the domain of CI protection has focused on how CI protection rules can deter employees from leaking CI (Hannah, 2006; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen and Puumalainen, 2007; Liebeskind, 1997). However, in practice it is difficult to ensure employees' compliance with CI protection rules (Hannah, 2006), in part because the enactment of those rules can lead to dilemmas for the individuals who are subject to them. Sisella Bok (1982), in her seminal book on secrecy and ethics, wrote that employees must often choose whether to comply with their employers' CI protection rules, or ignore the rules to get work done effectively and efficiently. Thus, CI protection and CI protection rules provided a rich context in which to study rule following and rule breaking. Next, we elaborate on the methodology that we used in order to gain insight into these issues.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In order to elaborate new theory (Lee et al., 1999) about rule following, we adopted a qualitative case study approach (Eisenhardt, 1989) and followed the procedures outlined by Gioia et al. (2013) for our qualitative data analysis. Once we had decided to focus on CI protection rules and articulated our research questions, we proceeded to select case organizations that would serve as rich sources of data to help us answer our questions.

Research Setting

The selection of cases for organizational research should be driven by the opportunity to better understand the phenomena of interest (Buchanan, 2012). Since the tendency to rely on secrecy to appropriate value from organizational knowledge is high in knowledge intensive industries, especially ones characterized by rapid technological change (Appleyard, 1996), we sought out case organizations that were operating in this context. At the time of data collection, our first organization, Scientific, had only been in operation for 10 years and its entire business was based on knowledge-intensive technology that it aimed to keep confidential. Our second organization, Technical, was a more established player in its industry, but also acknowledged that its core competitive advantage was a blend of proprietary technology and knowledge developed through its experience in the industry. Thus, the ability to effectively protect CI was of paramount importance in both organizations. Understandably, organizations whose competitive advantages are based on the protection of CI are wary of allowing outside researchers to study their operations, which in turn explains the dearth of studies where researchers are granted access to gather in-depth data on CI practices. Both organizations we studied therefore served as revelatory cases (Yin, 1994), because they enabled us to uncover hitherto unknown insights about CI protection rules and employees' reactions to them.

We began our data collection at Scientific. We then selected Technical as our second case organization, following Miles and Huberman's (1994) confirming or disconfirming sampling logic, in order to help us elaborate on our existing findings, identify possible exceptions, and add more variance to the data. Technical was a suitable choice because it differed from Scientific in many ways, including being 15 years older, employing ten times as many people as Scientific, and developing multiple products rather than the single product at Scientific. We expected that given Technical's size and age, that the CI rules would be more formalized, but we quickly learned that, while Technical's policy manual was more extensive than Scientific's, this did not create consensus around the rules or more rule following behaviour. In fact, our time spent at Technical was instrumental in helping us to flesh out the ways in which employees covertly broke or bent CI rules.

Scientific

At the time of the study, Scientific was in a stage of rapid growth, having nearly doubled in size since it was founded, and now employing approximately 40 people. Scientific was a single-product company that had only recently evolved from an academically oriented enterprise staffed by scientists working in a university laboratory, into a commercial enterprise with the goal of becoming profitable. That transition was proving to be challenging for the company for at least two reasons. First, the technology being used was so complicated that it was difficult for Scientific to convince potential business partners that their product actually did work. Second, there was an ongoing disagreement within the firm regarding whether or not they should still be devoting resources towards improving their understanding of how the product worked, or whether they should shift those resources towards more empirical research into what the product could do. Scientific was concerned with the protection of the physical design of the product, as well as knowledge about the product's functioning.

Technical

At the time we conducted this research, Technical was both older – just over 25 years old – and larger, employing approximately 400 people. Technical's products had been developed to the point that they were viable and they had a number of industrial applications. The promise of these key technologies had enabled Technical to grow from a small local operation into a company with overseas business ties and hundreds of employees. Technical invested a great deal of money into researching and developing its technology, and as a result, the company had posted losses in every year of its existence. The company's main objective for the next few years was to become profitable. To accomplish this objective, Technical would have to develop ways to manufacture its products more efficiently, as well as uncover new commercial applications and markets. There were two aspects of Technical's CI that required protection: the physical design of their products, and the knowledge behind the products' designs.

Data Collection

The data for this research consist of semi-structured interviews with employees in these two firms. A total of 55 interviews were conducted (24 at Scientific and 31 at Technical). As a group, the interviewees were highly educated: over 85 per cent had at least an undergraduate degree, and over one third had either a Master's degree or a Doctorate. The average age was 42, and 41 of the 55 interviewees were men. Most of the participants indicated that they enjoyed their jobs and working for their companies.

Data collection was carried out over a six-month period, beginning at Scientific. Because all of the employees at Scientific regularly handled CI and the company was small, we were ultimately able to interview 70 per cent of the workforce, including several members of the top management team. At Technical, we employed a combination of purposive and random sampling. We began by purposively selecting departments where employees regularly dealt with CI, and with the support of the organization, we employed random sampling within each purposively selected department to ensure diversity in the views of the people we interviewed. This helped us to capture the most important features of the organizational contexts, therefore enhancing the ecological validity of the findings (Lee, 1999).

During our interviews, we aimed to elicit participants' views about their organization's CI and CI protection practices. The interviews were conducted on-site at the organizations in a private office, and ranged in length from 30 to 60 minutes. We assured our participants of anonymity, explaining that their employers would never be provided with transcripts of the interviews, and that we would not divulge information that could allow individuals to be identified. We considered our participants to be ‘knowledgeable agents' and worked to ensure that our questions were open-ended to encourage them to reflect in depth on CI in their organizations and in their work using their own ‘voices' (Gioia et al., 2013). When interviewees offered a new or unanticipated response, the interviewer used probes to encourage them to expand upon their statements. We modified the interview protocol as we proceeded in order to take advantage of emerging themes (Spradley, 1979), including asking about rules and events that employees in our early interviews focused on. The flexibility of our approach helped to ensure that we were open to the emergence of new concepts (Gioia et al., 2013). All interviews were recorded and transcribed. In total there were 674 pages of interview text. In addition to our interviews, we reviewed the written CI rules. In both organizations, these rules were generically worded and often interpreted in different ways by different employees. We also consulted extensively with the most senior managers in each organization who were responsible for CI protection, discussing emerging findings with them, seeking clarification on particular events, and deepening our understanding of both firms' CI protection regimes.

Data Analysis

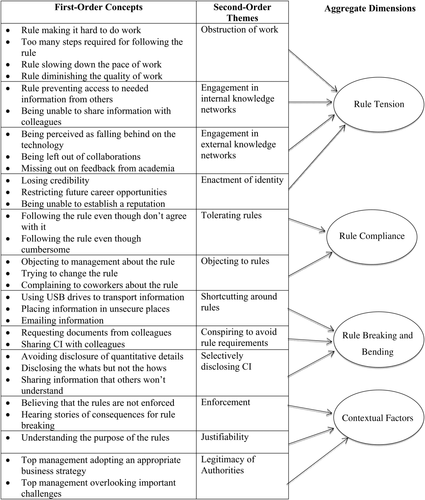

Following the procedures described in Gioia et al. (2013), our data analysis consisted of four main phases. First, narrative case summaries were written for each interviewee to capture their overall experiences and perspectives. Second, interview transcripts were analysed to develop first-order concepts. Third, we organized our first-order concepts into more abstract second-order themes, and identified connections amongst these themes to build aggregate theoretical dimensions. Finally, using the data structure and summaries, we identified connections between our concepts, themes, and categories to develop a grounded theory of employee responses to CI rules. Figure 1 includes the first-order concepts, second-order themes, and aggregate theoretical dimensions that we drew from to develop our theory.

Data structure

Phase 1: Interview summaries

In the first phase, we prepared summaries for every interviewee in the study. Each summary included information about the interviewee's role at their company and their overall understandings of and experiences with CI and CI rules in their work. These summaries, combined with the extensive amount of time spent in the research settings, were designed to help us develop a clear understanding of the experiences and perspectives of the participants (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). While the coding process allowed us to identify patterns that were representative of the entire set of interview data (Lee, 1999), the summaries helped us to ground those observations in the experiences of individuals. The summaries also kept us alert to idiosyncratic, but interesting aspects of particular cases that could stimulate new insights or provide illustrations of our findings (Hannah and Lautsch, 2011).

Phase 2: Coding for first-order concepts

The goal of the second phase of our analysis was to code anything in the text of the interviews that could pertain to CI and the CI rules. Initially, the first and second authors coded several of the same interviews and arrived at a consensus on a starting list of first-order codes. After this initial set of codes had been defined, the second author continued coding interviews in consultation with the first author. As new codes emerged, they were added to a coding dictionary and earlier interviews were re-read to check for the presence of those codes. Throughout this phase of the coding, we aimed to remain as close as possible to the language and experiences of our participants (Gioia et al., 2013). Using the NVivo 7.0 software program helped us to recall and adapt our codes, as well as organize the almost 100 first-order codes we generated. A code–recode check was conducted on ten of the interviews and an intra-rater reliability of 92 per cent was achieved, which exceeds Miles and Huberman's (1994) code–recode standard of 90 per cent. All differences were explored and resolved. We have included a selection of the first-order concepts that figured prominently in our analysis, along with illustrative quotations from the interviews, in Table 1.

| Second-order theme | First-order concept | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Obstruction of work | Rule making it hard to do work | ‘Purely based on what we've done to restrict people to the programs… A lot of people saying it restricts them in doing their job.' [Technical] |

| Too many steps required for following the rule | ‘They don't want to follow the steps of creating like a workbook folder. It's a little cumbersome… you have to call up the helpdesk, place a call, we'll create a little workbook folder, we'll have you one person as an owner and another person added to that group so you guys can exchange folders and that, right?' [Technical] | |

| Rule slowing down the pace of work | ‘So any time I need access to a new part of the directory structure, I waste, I don't know. I mean, 10, 15 minutes but in terms of real dollars that is real time.' [Technical] | |

| Rule diminishing the quality of work | ‘People that were once seeing everything and now suddenly they're shut out… I will create a document and put it in the database and then if I send that out to the teams they can't actually see that document… It's very odd that they're supposed to be the people designing it.' [Technical] | |

| Engagement in internal knowledge networks | Rule preventing access to needed information from others | ‘[The rules are] over-protection meaning when you can't get information on other projects that might be useful for me or, or information is kept at a higher level.' [Technical] |

| Being unable to share information with colleagues | ‘The fragmentation that you see, too, in discussions with people now because people are worried about sending email and you know, getting maybe some kind of disciplinary action for violating the policy, right? So there's that kind of feeling now where things are closing down, right?' [Technical] | |

| Engagement in external knowledge networks | Being perceived as falling behind on the technology | ‘I don't know, I think it's good to – I think if you stay in secrecy for ever and ever it doesn't help. You have to be out there a little bit more.' [Scientific] |

| Being left out of collaborations | ‘The science part should be more open and should accommodate more experts because we have only one theorist, and… [he doesn't know everything]… in the world.' [Scientific] | |

| Missing out on feedback from academia | ‘We need to actually be in discussions with academia, in particular, because we have hit circumstances here where we could use outside help.' [Scientific] | |

| Enactment of identity | Losing credibility | ‘We hide in our hole here, and don't communicate with the proper world around us, it's really professional suicide for those of us who have strong academic backgrounds… we have to be showing the world that we are in fact doing credible, useful things, we're not inventing cold fusion or anything like that.' [Scientific] |

| Restricting future career opportunities | ‘If somebody tells me that I cannot publish anymore from now on that then means that I cannot find a job that I want from now on.' [Scientific] | |

| Being unable to establish a reputation | ‘You try to hire someone out of academia who's been building a career and reputation … Yeah, you're just going to be quiet and hide. It doesn't work. It doesn't work for me.' [Scientific] | |

| Tolerating rules | Following the rule even though cumbersome | ‘[The CI rule] was very frustrating. But at the same time, when I understood why, I handled it. You know? I mean, I went, okay, okay. So in the bigger picture, this is a good thing to do.' [Technical] |

| Following the rule even though personally don't agree with it | ‘I guess I understand [the publication ban] from a business framework, it's just a little frustrating as a scientist.' [Scientific] | |

| Objecting to rules | Objecting to management about the rule | ‘I wrote that paper and submitted it just over a month ago for publication. So it means some things are leaking out… management has just sort of begrudgingly given in, because those of us who are in the back lab who have been complaining about this were ultimately shown to be right.' [Scientific] |

| Trying to change the rule | ‘And even I argued that we should be able to publish some stuff if we had filed for IP protection.' [Scientific] | |

| Complaining to co-workers about the rule | ‘Now it's mostly people know they can't publish and they just complain about it.' [Scientific] | |

| Shortcutting around rules | Using USB drives to transport information | ‘There's no software system… saying, oh, a USB drive is connected to this computer and does a flag up on it somewhere… the reason I know that is I've downloaded stuff for myself during the day.' [Technical] |

| Placing information in unsecure places | ‘People were posting on [the company blog] without the OK from the IP department.' [Scientific] | |

| Emailing information | ‘Your boss says send something to this and you go, you're supposed to be on the secure email list and get automatic encryption, they're not. It's like, what do you do? Find somebody else in their company to send it to? Eventually the boss says, no. Just send that… At the manager level it's every single week probably hundreds of emails go out through unsecured email lines to our partners.' [Technical] | |

| Conspiring to avoid rule requirements | Requesting documents from colleagues | ‘[Interviewer] So there's no sort of you know quick way of getting one document? [Interviewee] There is if you know somebody who has access to it.' [Technical] |

| Sharing CI with colleagues | ‘If I needed to have an electronic component built and they needed to know the dimensions of say the product, right? And they didn't have access to it, you know? I would send over a document that says here's the dimensions. The circuit board goes here sort of thing, right?' [Technical] | |

| Selectively disclosing CI | Avoiding disclosure of quantitative details | ‘You can get around it by not being too quantitative in the details.' [Technical] |

| Disclosing the whats but not the hows | ‘Keep it short and simple… you don't have to fill in the details, just say, “We use tin.” Because you have to at least tell them what material to use. But then you wouldn't tell other people that this is the company that we use, this is the process that we use with them.' [Scientific] | |

| Sharing information that others won't understand | ‘It all depends on the circumstances because some companies have nothing to do with that so… you can tell them even more and they won't get it because they just, they don't know it.' [Technical] |

Phase 3: Developing second-order themes and aggregate dimensions

The third stage of the analysis began by drawing connections between the first-order concepts to develop more abstract second-order themes. During this phase we relied on axial and selective coding procedures (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). We worked to identify those codes that we believed were most representative of the data, so we focused on codes that appeared more frequently. A code had to be mentioned by at least six interviewees (approximately 10 per cent of the participants) in order for us to incorporate it into our theorizing as a second-order theme. We also drew upon the interview summaries at this point because they helped us see how categories might be related to one another. Once we had identified our second-order themes, we considered whether and how they might be connected to one another. This allowed us to identify overarching aggregate dimensions, which helped us to consider broader interconnections at a highly abstract level to develop our grounded theory.

Phase 4: Constructing our grounded theory

In developing our theory, we drew on both the second-order themes and aggregate dimensions, and focused on how they systematically related to one another. While we used memos throughout all stages of the coding process, they were particularly important during the theory development phase, as we revised and elaborated our emerging theoretical ideas. Our goal was to develop a grounded process theory that explained why and how employees responded to CI rules. We identified how employees experienced tension between the CI rules and other expectations they faced, and worked to identify aspects of the context that influenced employees' reactions to those rules. In keeping with the best practices for this type of research, we developed our theory by iterating between the data, our emerging theory, and the literature (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). For example, Lehman and Ramanujam's (2009) concept of interconnectedness helped us to understand why the theme of tension was so prevalent in our data. We continued to compare our ideas to both the summaries and transcripts to ensure that our more abstract interpretations continued to resonate with the data. We constructed a variety of provisional theoretical models, and refined them until we arrived at the one to be presented in this paper. We have included this model in our discussion, but first we will share the details of our results.

FINDINGS

We begin the presentation of our results with data that describes the CI rules at Scientific and Technical. We then explore why some of those rules led to tensions for employees and others did not. We elaborate on the types of tensions that emerged, and describe how employees reacted to them. Table 2 provides a summary of some of the CI rules at both organizations, including the rules that employees told us led to tensions. For those rules, we indicate both the type of tension and employee responses.

| Rule | Description | Form of CI tension caused by the rule | Employee response to CI tension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification badge (Technical and Scientific) | Employees are required to wear badges with their photo and identifying information at all times when inside the company's buildings. | None | None (no tension) |

| Signing of NDA (Technical and Scientific) | Employees are required to sign a non-disclosure agreement that prohibits unauthorized disclosures of confidential information as a condition of employment. | None | None (no tension) |

| USB ban (Technical) | Employees are not permitted to use USBs or other portable memory devices to transport data within or outside the organization. | Obstruction | Shortcutting, conspiring |

| Information system (‘Sharp') access restrictions (Technical) | Employees can only access documents in the information system that pertain directly to their line of work without following a series of steps to obtain formal access permission. | Obstruction, knowledge networks | Conspiring |

| CI sharing restrictions (Technical and Scientific) | Employees are not permitted to share confidential information with outsiders unless granted express permission from the legal department or top management. | Knowledge networks | Selectively disclosing |

| Publication restrictions (Scientific) | Employees cannot publish the results of research conducted at the organization unless approval is obtained from top management. | Identity | Objecting exiting |

The CI protection regimes at both Scientific and Technical consisted of many different rules, including written agreements that employees were required to sign, general rules that everyone was expected to obey, and more selective rules that applied only to individuals who worked in a certain physical area, with a particular type of information, or in a particular role. Some of these requirements seemed to have little impact on employees' day-to-day working lives. For example, one rule common to both companies required everyone to wear identification badges when inside company facilities. Employees rarely cited that rule in their conversations with us. Even though they dealt with it every day, they simply complied with it. In contrast, other CI rules had drawn the attention and often the frustration of employees, because for employees to comply with the rule, they had to compromise on some other expectation that they faced. In order for rules to elicit these kinds of reactions, they needed to be (a) interconnected with other activities that employees wanted to engage in, and (b) lead to the experience of tension for employees. Next, we explore each of these characteristics.

CI Rule Interconnectedness

The CI rules at Technical and Scientific were often interconnected with other organizational activities, meaning the rules and the activities were ‘functionally linked or interdependent' (Lehman and Ramanujam, 2009, p. 651). For example, the rule requiring identification cards was linked to the activity of physically entering the buildings in which the companies' operations were located. Another example is a rule that required Technical employees to cover physical technology when they were taking it out of the building. Since CI could be gleaned from looking at the design of some of Technical's products, any time these products were taken outside they had to be covered in order to prevent outsiders from observing the technology and possibly taking pictures of it. There was variance in the extent to which rules were interconnected with other organizational activities. While some rules were connected to a single activity, such as identification cards to entering the facility, others were connected to a greater number of activities. An example of a broadly interconnected rule is the non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) that all employees were required to sign as a condition of employment. NDAs are intended to apply to all kinds of activities and all kinds of CI, and typically include general instructions regarding signees' obligations to protect CI.

When CI rules were interconnected with other organizational activities, this created the possibility that the rules would make it more difficult for employees to complete those activities. In some cases, in order for employees to comply with CI rules, they had to compromise on an activity that they believed was an important part of their work. For example, the requirement to put a physical cover on technology when outsiders were present prevented employees from working on that technology until the cover was removed. We term this kind of interconnectedness disruptive. In other cases, CI rules were not disruptive. For example, although the NDAs were broadly interconnected with other organizational activities, they rarely influenced employee behaviour because they were so generally worded that they were of little use in helping employees decide what or what not to do in a specific situation.

CI Rule Tensions

[Technical] is saying we only do [A], we don't do [B]. So all of this stuff that we consider IP about [B], there's no reason to keep that secret… We ought to be telling our customers as much of that stuff as we can, right? It's not in our interest to keep it secret. It's in our interest for our customers to know it. There's still people trying to keep that stuff secret. There is no rationale.

To be clear, by rule tension we are referring to an individual experience of tension, which appeared to provide the fuel for employees to break or bend the rules causing the tension. We observed three types of rule tension. The first was when CI rules slowed down the pace at which employees were able to accomplish required work tasks, which we refer to as ‘obstruction tension'. The second type of tension, which we call ‘knowledge network tension', occurred when employees perceived that rules threatened their ability to acquire information from or share information with others. A third form was ‘identity tension', which arose when CI rules prevented employees from acting in ways that were essential to their professional identities. Next, we present examples of each type of rule tension and the rules that preceded it.

Obstruction tension: slowing the pace of work

We found there was a security breach. And people were giving us names and said they suspected these names might have something to do with it. So we ran logs on that particular system and what we found as well is that [someone] was just dumping stuff out. It was basically, I think 15 seconds between, going from [secure] areas top to bottom extracting information. So if you have 15 seconds between information going out, you know [someone] is really dumping it onto a, a hard drive basically.

One of the pet peeves I have is they don't like us to use USB flash drives, but not all the computers downstairs are networked and you have these big monster files and you have to find a way to get it from there to your desk or to the network to work on it.

Not being able to transport information freely within the company had the potential to cause delays in some employees' work, particularly in cases where they needed to have access to large data files. Rather than simply plugging in and copying the data, they would have to develop another alternative. Until recently, there had been an alternative: to access documents via the company's knowledge management system, which we refer to as ‘Sharp'. Before the CI rule changes, any employee could access all of the files in the system at any time. Many employees spoke positively about this arrangement. As one explained: ‘A couple of months ago, [Sharp], which is a wonderful system, you used to go in and find anything. You know? You could look up any document.'

However, a second change made in response to the information leak was to implement access restrictions in the Sharp system. As a result, employees were now only permitted to view files that management had deemed to be directly related to the projects (in the vernacular of the organization ‘programs') that the employees were currently working on. In order to gain access to restricted files, employees had to follow a series of steps designed to prove that they needed the information. Additionally, to preserve the integrity of the access restrictions, employees were required to store the files they created in secured folders to prevent unauthorized employees from viewing them.

So when one needs access to a certain directory or certain info you don't know who to go get it from… Well, it just slows everything down to send an email saying, ‘Well, can you give me access to this?' And they say, ‘Well, you need a letter of approval.' And you go, ‘Well, who do I get it from?' And they say, ‘Well the program manager.' ‘Well, who is that?' ‘Well, I don't know, you should know. If you don't know, why would you need access to this?' You get that stupid kind of discussion.

Part of the problem, is that it's quite cumbersome to get access to a folder so when you need it you end up waiting a few days to get it… You can't get the data to make your graph to make your presentation because, you know, our development extends a lot of years so you can't just be working in a small box. You have to be able to access these other segments of the company.

Knowledge network tension: disrupting information flow

If we can convince the academic world that we're doing good stuff, they're going to contribute. Theorists will see what we're doing, work with our hardware designs, and run with it, and see what comes out of it – that helps, that's great. If we see people working on other problems related to the way we make our devices, that's great too. It's free research for us, effectively.

We, for instance, had a situation where one of our theorists had prepared something over 8 months ago, was not allowed to publish it, for the past 8 months has been sitting on the result, finally it's been let loose, and immediately an answer has come back from academia that someone has found a serious problem with it… The fact that this result may not stand has serious implications for us. And we should have known that 8 months ago.

The downside [of the rule is] that we're seen as falling behind on the technology. So everyone else in the industry is sharing that type of information with each other, forming collaborations, talking, learning from each other. We're not because we're protecting our knowledge. So we miss out on that knowledge from the other people until they have actually published it. And we miss out on everyone else's perception. They think we're falling behind when in a lot of cases we actually knew it… before the other companies did. But we didn't ever talk about it.

That was very frustrating to me two or three months ago when I was looking for work that I had done previously. Looking for something that was, you know, not related to what I was currently doing but there was important information, something that I wanted.

Identity tension: preventing publication

Out of all the rules that constrained how employees shared information with outsiders, there was one type of rule that drew a great deal of attention at Scientific: rules that restricted the publication of scientific knowledge. The publication restrictions were new to Scientific, having been instituted just before the hiring of the company's current CEO less than one year before. This reflected a change in the direction that the company was pursuing. When Scientific was founded it had an academic orientation, and for many years employees were permitted to publish the results of their work. Several employees had joined the company with the expectation of being able to publish their research. However, senior management now felt that the company's technology had been developed to the point where it was necessary to shift the focus towards commercialization and away from general academic inquiry. As a Scientific manager explained: ‘As the company evolves and matures, people are less interested in the underlying technology than they are in the application.' In order to make commercialization profitable, keeping the results of experiments confidential became a priority. While a small number of papers had been published since the restriction was put into place, it now took much longer to do so, and everyone was aware that publication was conditional upon management's belief that releasing the information would not harm the company's ability to be a first mover in commercializing the technology.

This was a source of what we term identity tension. The ability to publish papers in academic journals seemed to be fundamental to the professional identities of some of the company's more academically oriented employees. This group of employees had been recruited from academia because of their specialized knowledge and had been led to believe that they would be able to carry on with their academic careers from within the company. They had continued to publish their research until recently. Now, as a group these employees had two papers they were hoping to publish, but which management forbade them from doing for the time being. As one of Scientific's researchers explained, if the outside world began to perceive the company's work as bad science, he ‘might as well go to chef's school or something, because I'll be done as a [scientist].' Other academically oriented employees experienced similar identity tensions. As one said: ‘The definition of a scientist: it's publication.' These researchers needed to find a way to reconcile their sense of being scientists with working for a company that had stopped allowing them to pursue work that was fundamental to their identities.

All of the employees who wanted to publish were also very pessimistic about the likely results of the publication restriction for the company. ‘I've told people that the best analogy is that we're standing on the edge of a cliff where we're either going to sprout wings and fly, or we are going to fall. And it's gonna hurt.' They felt the publication restriction was increasing the chances that the company's whole reason for being was going to be a flop, making all of the time and money spent on trying to commercialize the technology an utter waste.

Resolving Rule Tension: Breaking or Bending CI Rules

Next, we present our findings regarding how employees reacted to obstruction, knowledge network, and identity tensions. We discuss three ways in which employees chose to break or bend CI rules, which we term shortcutting, conspiring, and selectively disclosing. We also discuss circumstances under which employees would continue to follow rules in spite of the rule tension, a behaviour we call tolerating, and explain why employees also sometimes engaged in objecting.

Shortcutting

I once had a thumb drive that I was traveling back and forth and plugging in and taking documents. I don't think they were the kinds of documents that if leaked would get us in trouble, but it's fairly common practice. Although our policy said we could not do it.

Many employees appeared to believe that what was usual – what was, as this employee put it, ‘fairly common practice' – was to break this rule, and to do so covertly so that they would not be caught and punished. Most of the employees who engaged in shortcutting described their behaviour as being the norm in their organization. They tended to see this practice as harmless because they felt they would still be careful with the information and would not put it at risk, and also believed they were unlikely to be caught and punished because Technical did not monitor the use of USB drives. Further, given the small size of USB drives, it was easy for employees to use them surreptitiously.

Conspiring

I've just had to send the document to them through email. Because that's been the only way. I said to them, well you should write to these people to get access but then they always say, well, we're not part of the [project name]. So it's something they could do, but I guess they have to jump through these loopholes and get signed up.

Conspiring allowed workers to gain access to information more rapidly than if they had followed the rules, so it alleviated obstruction tension. It also enabled employees to enact and reinforce internal knowledge networks, because workers would covertly share CI with one another.

While the likelihood of getting caught when conspiring may be higher than individual shortcutting, this factor appeared to be mitigated by trust in one's co-conspirators. Some interviewees generally trusted their co-workers and believed they would not inappropriately disclose CI because doing so would harm their employer and by definition themselves. Further, they believed that other organizational insiders could probably eventually get access to whatever CI they wanted anyway, so it was pointless to try to deny them that information. As one employee explained, ‘If someone wanted to take something, they probably can. They say, you know, locks are for honest people.' Other employees were more selective about trust, only being willing to share information with people they had worked with previously and who therefore had some awareness of the projects they were working on in order to assess whether their need for information was legitimate.

Selectively disclosing

While employees maintained internal knowledge networks, at least in part, by conspiring to share CI, they would maintain their external networks by selectively disclosing information. When discussing CI with outsiders, employees would sometimes share certain aspects of the CI but not others; specifically, employees would only disclose aspects of the information that they personally believed did not need to be kept confidential. By doing so, they would be able to maintain their place in external knowledge networks, while still in their opinion protecting the company's CI. They accomplished this objective by not sharing details about the technology. In particular, they were careful: (1) to disclose the ‘whats' but not the ‘hows'; and (2) to not disclose quantitative data.

Like recently, I was going to the supplier for the design of a piece of equipment we were buying and of course they were asking me questions how you do that, why you do that and so on. Basically I try to generalize this stuff, what we do here and just give them, just information. We take a piece of paper like that and we compact it with a machine like that.

Similarly, if asked questions about the company's technology, employees often still provided answers, but ones that they did not think would enable outsiders to figure out how the technology actually worked. A Technical employee explained: ‘We can just say it starts up in this many seconds, but don't tell them how we're getting there.'

Given the nature of both companies' technologies, employees believed that, as one Scientific employee put it, the ‘devil was in the details', and in particular the quantitative details that could enable outsiders to figure out the mathematics or engineering behind the products. They would therefore leave out specific numbers when sharing the results of experiments with outsiders. A Technical employee described how he might do this: ‘Even just putting together a graph of results, you know, like just taking, wiping a legend of sort of maybe sensitive information and just keeping everything kind of generic, whether it be A, B, C, curve.'

Tolerating

Sometimes I remember when the tours are coming and we have to cover the [technology]. Some people are getting angry down on the floor. [They] said ‘Again? What are we hiding here? Because I don't know if anyone is really interested, you know, whatever we are doing. [We] don't really have to cover it.' But, on the other way I think we do. With the technology we have at hand right now it's so easily, so easy you know to, to have a very, very small camera or something to, to take a picture or, you know, copy something.

Objecting

Lastly, some employees reacted to tension by objecting to the rules, which involved communicating dislike of a rule to management with the goal of having a rule changed, while still complying with the rule's requirements. We heard about objecting most often when Scientific employees were lobbying to have the rule restricting publications changed: ‘I thought – and I signed a letter, too – to the extent that I thought [the publication restriction] was a little draconian and probably inappropriate.' In some cases, employees reported a degree of success. One explained: ‘This publication policy has holes in it now because people like myself have been pushing continually.' However, none of the scientists we spoke with were satisfied with the status quo and they continued to push for further change. We also heard about, but did not directly observe, instances where employees had left the company as a direct result of the tension caused by the publication rule. Two workers left Scientific after the publication restriction was introduced, and (according to some former co-workers), after their efforts at objecting to the rule had no effect. One of the employees who remained with the company also noted: ‘Tension was getting to be enough that I started to field jobs in the U.S. a few months ago.'

There were three factors that were relevant to employees' decisions to tolerate rules and/or object to them rather than breaking or bending them. First, employees sometimes perceived that a rule was justified because obeying its requirements would effectively protect their organizations' CI; second, employees considered the legitimacy of the rule-making authorities; third, employees took into account whether they would be likely to be caught and potentially punished for breaking or bending rules, that is, whether the rules would be enforced. We discuss each of these factors in turn.

Rule justifiability

Employees were more willing to tolerate rules that they personally believed were justified because the rules were necessary for protecting the organization's CI. Employees' assessments of justifiability appeared to be cued by the experience of tension. When employees encountered a disruptive rule, they considered whether there was a connection between the information and the company's competitive advantage and whether breaking the rule would pose a threat to the company. When they understood the importance of protecting the information and believed rule breaking did pose a threat, they viewed the rule as being justified and in turn were more willing to follow it. The example presented above, of an employee who tolerated the rule requiring physical covers to be put on technology when outsiders toured the facilities, illustrates justifiability, because that employee believed the cover was necessary to prevent people from stealing CI. Another example is a Technical employee who, unlike some of his colleagues, tolerated the changes in Sharp because he believed that a former employee had been the cause of an earlier CI leak. This knowledge made him appreciate the risk posed by insiders and so he was more understanding of access restrictions for insiders even when those restrictions were personally disruptive.

Legitimacy of rule making authorities

That's not something that rides high on the minds of people such as [the new CEO]… there's no emphasis upon communicating with the outside world. It's about making a product. You make a product and the product proves itself. That's all fine if you're working within the confines of well-known properties and materials, and well known devices. But of course what we're doing is extremely exploratory.

However, other employees, who viewed the business acumen of the new CEO as being more important to the organization at its current stage of development, ascribed greater legitimacy to the CEO. They viewed the CI rules he implemented, and particularly the publication restriction, as important to the progression of the business and therefore were more willing to tolerate those rules. One such interviewee explained: ‘Publishing ban of confidential information is the essence of [Scientific], in my sense. There are other companies out there with billion dollar budgets to produce [our technology]. We're not at that financial level… the publishing ban I think was a necessary step.'

Rule enforcement

Employees also tolerated rules that they expected to be enforced. At Scientific, many employees strongly disliked the publication restriction, but none of them tried to defy it, probably because they knew they could not covertly publish their research findings, and would be punished for even attempting to do so. On the other hand, employees at Technical who participated in shortcutting and conspiring around other CI rules noted: ‘There wouldn't be a consequence I think even if you had confidential information because the policies are ill enforced.' Thus, enforcement could deter employees from bending and breaking rules.

Everybody kind of can get access to the documentation… We've been now in business more than 15 years. And having said that, even like, a whole lot of time you find very sensitive information is on the you know, copy machines and, or people forget to pick it up from the copy machines… I think we are missing the culture. People haven't been trained.

In these cases, a lack of enforcement of CI rules undermined employees' perceptions of the legitimacy of the authorities.

DISCUSSION

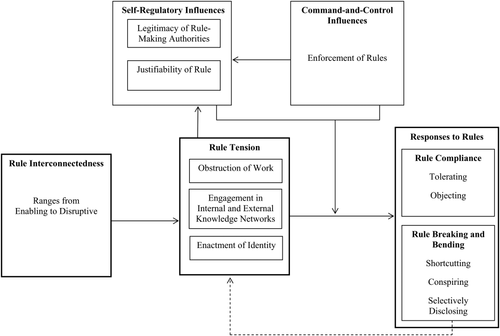

We began this paper by highlighting the importance of rule following in organizations. Having chosen to focus on CI protection rules, we asked: Why do employees follow or break CI protection rules? If they do not follow the rules, how do they break them? Our analysis of CI rule following and rule breaking in two high-technology organizations showed that CI rules were often interconnected with other expectations that employees faced. These interconnections sometimes caused tensions for employees, which in turn led employees to break or bend the rules. Figure 2 presents a schematic diagram of the theory that we elaborated from our findings. As that figure depicts, CI rule interconnectedness can range from enabling to disruptive. Disruptive interconnectedness causes tensions that in turn can lead to rule bending and rule breaking. The relationship between rule tensions and rule following behaviour is in turn moderated by command-and-control factors (i.e., rule enforcement) and self-regulatory factors (i.e., justifiability of rules and legitimacy of rule-making authorities), such that employees are more likely to follow disruptive rules that are enforced, justifiable, and enacted by legitimate authorities. Further, CI rule tensions can influence the self-regulatory factors, because they cue employees' assessments of the justifiability of the rules, and may cause employees to revisit their opinions about the legitimacy of rule-making authorities. Similarly, CI rule enforcement can influence employees' beliefs about the legitimacy of the rule-makers, an idea we represent in Figure 2 with the arrow connecting rule enforcement to the self-regulatory influences.

The impact of rule interconnectedness and tension on rule following

In the discussion that follows, we elaborate on the insights depicted in Figure 2, and explain how they add to the literature on rule following. Briefly, our findings highlight the importance of understanding three understudied aspects of the rule following process: (1) how rules can be interconnected with other expectations that employees face, sometimes in disruptive ways; (2) how and why disruptive interconnections cause tensions that can shape rule following behaviour; and (3) how employees may react by bending the rules that cause tensions.

Rule Interconnectedness and Disruptiveness

As noted earlier, while the literature on rule following has noted that rules can be interconnected with other rules (Lehman and Ramanujam, 2009; March et al., 2000) and organizational activities (Hale and Borys, 2013), it falls short of a complete understanding of the nature and implications of these interconnections. We suggest that by considering the extent to which rules are interconnected, and how the rules are interconnected, we can enhance our understanding of employee rule following behaviour.

We found that some CI rules were connected to many different expectations, while others were narrowly interconnected. As we discussed earlier, employees signed non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) related to many different kinds of organizational activities, because there were many ways in which employees could disclose CI to outsiders. In contrast, the publication ban at Scientific pertained to only one activity, publishing the results of scientific research. Lehman and Ramanujam (2009) predicted that for rules originating outside of organizations (i.e., laws), greater interconnectedness with internal rules would increase organizational rule following. We found that when it comes to internal organizational rules, interconnections sometimes created the kinds of tensions that led to rule bending and rule breaking.

To understand how and why some rule interconnections cause tension, it is useful to draw on the insights of Adler and Borys (1996). In their analysis of bureaucracy, Adler and Borys (1996) suggested that rules can be enabling, in the sense that they help employees get work done, or coercive, forcing employees to act in certain ways. They further suggested that employees were more likely to react positively to enabling rules than to coercive ones. What we found, however, is that employees reacted negatively not when rules were coercive, but rather when they were disruptive. This idea is consistent with other research. For example, in their study of information security policy compliance, Bulgurcu et al. (2010) found that when employees believed that the policies impeded their work, they had a more negative attitude towards those policies and reduced intention to comply with them. Other studies of rule following have similarly found that employees are less likely to follow rules that interfere with their work (Elling, 1991; Hale and Borys, 2013). Further, disruptiveness seems like a logical opposite to enabling: rules can make it easier for employees to complete work tasks (enabling), or make it more difficult to do so (disruptive). In the latter case, the rules cause tension.

Rule Tension and Rule Following

We identified three types of tensions that employees faced with regard to CI protection rules: disruptions to the pace of work, to valued knowledge networks, and to employees' identities. Rather than an exhaustive list of the types of tensions that can occur, the three tensions we identified are illustrative of the ways in which rules can come into conflict with other employee expectations. The tensions we observe appear to be examples of role stress, which occurs when employees perceive that there are conflicts between the expectations of different roles they engage in (Bacharach et al., 1991; Jackson and Schuler, 1985). While the idea that employees experience tension between roles is not, therefore, a new one, what is new to the rule following literature is how these tensions influence employees' decisions about whether to follow rules. To explain this, we return to the two approaches to rule following identified by Tyler and Blader (2005): command-and-control, and self-regulatory. As we noted in the results, the relationship between rule tensions and rule following behaviour is influenced by command-and-control factors (i.e., rule enforcement) and self-regulatory factors (i.e., justifiability of rules and legitimacy of rule-making authorities). We include these factors in our theoretical model, and depict them as moderating the relationship between tensions and behaviour. We further suggest that our findings have three implications for these perspectives and the relationship between them: (1) when rules cause tensions, this leads employees to scrutinize the self-regulatory influences on rule following; (2) the self-regulatory and command-and-control influences on rule following can be complementary, not competing, as has been previously thought; and (3) at a certain point, command-and-control influences are likely to trump all other concerns.

A self-regulatory perspective emphasizes that intrinsic factors, particularly workers' perceptions of the legitimacy of rule makers and their agreement with the values expressed by their organizations and by rules, have a powerful impact on rule following (Sutinen et al., 1990; Tyler and Blader, 2005). We found that when employees experienced tension between CI rules and other expectations, they did three things that are pertinent to self-regulatory influences on rule following. First, they questioned the legitimacy of rule-makers, blaming them for creating a work environment where employees faced competing demands, and concluding that the rule-makers are uninformed about the impact of the rules they have created. This was a common reaction among Scientific employees who were barred from publishing their findings: they wondered why top management had hired workers who wanted to publish research, then forbade them from doing so. They also tended to believe that top management simply did not understand the negative impacts of not publishing.

Second, workers would subject their own work to a self-regulatory comparative evaluation, assessing the extent to which the work they were doing was more or less important than the rules they were being pressured to follow. This is where the justifiability of rules played a key role, because when employees believed rules served a useful purpose, they were more likely to adhere to their requirements even if doing so made it more difficult to meet other expectations. Justifiability is related to what Son (2011) has referred to as rule legitimacy in his study of compliance with information security procedures. Justifiability can be conceived of as the legitimacy of disruptive rules in particular: employees ask themselves whether the burden of compliance is worth the negative impact on their work. Our research extends understanding of how employees arrive at assessments of justifiability. The first factor that our participants considered was the importance of the work being disrupted, and the second was the degree of disruption. Employees were more likely to consider rules that caused a minor disruption of relatively unimportant work to be justifiable, and were in turn more likely to follow those rules. However, when the rule caused substantial delays or delayed important work, justifiability was diminished, unless the employee could see a clear connection between breaking the rule and a high risk of harm to the organization. Thus, it is not only an assessment of whether rules are proper and important to the organization (legitimacy) that is likely to influence rule following behaviours, but more specifically the implications of compliance relative to the risks associated with breaking the rule (justifiability).

Another way in which our findings add to the literature is by suggesting a more complicated relationship between the self-regulatory and command-and-control influences on rule following than has previously been contemplated. In their arguments about the relationship between rule enforcement and rule following, Tyler and Blader (2005) drew on research in intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Kohn, 1999) to argue that a command-and-control approach to rules can actually undermine employees' intrinsic motivations for complying with them. Our research points to two refinements of this model. First, when employees believed that a certain CI rule was enacted by legitimate authorities and was justifiable, they also believed that the individuals who broke that rule should be punished. If the rule was not enforced, this reflected badly on the individuals who should be enforcing the rule, and also either directly or indirectly on rule-makers: directly if the rule-makers should be enforcing the rules themselves, and indirectly if the rule-makers were not making sure that lower-level managers were enforcing important rules. Further, the enforcement or lack of enforcement of rules also sends signals to employees. Guo and Yuan (2012) suggested that the command-and-control approach of applying organizational sanctions acts as a social cue that communicates the importance of the rules, and that people regulate their own behaviour accordingly. We found that when CI rules were not enforced, it suggested to employees that breaking and bending CI rules was acceptable behaviour.

A third way in which our study adds to previous research is by clarifying the role of enforcement in rule following. For the most part, we are in agreement with previous research that has found that employees are more likely to follow rules if they believe they will be caught and punished for disobeying them (Hale and Borys, 2013; Herath and Rao, 2009; Hovav and D'Arcy, 2012). However, other studies have found that under many circumstances, employees' perceptions of enforcement are less important than other intrinsic factors such as personal values (Tyler and Blader, 2005) and general rule following tendencies (Guo et al, 2011). We would point out, however, that if an employee is certain to be caught and punished severely for breaking a rule, they are unlikely to break it, even in the face of strong self-regulatory pressures to do otherwise.

Rule Bending as a Response to Rule Tension

To conclude the summary of our contributions to the literature on rule following, we will expand upon our ideas of how employees react to rules by following them, breaking them, or engaging in what we term rule bending. While this term has been used before in other literatures, including public policy (Sekerka and Zolin, 2007) and criminology (Loyens, 2014), it has tended to be conceptualized as a description used by rule-breakers to frame their actions in a more positive light. For example, Loyens (2014) found that some police officers described the mistreatment of suspects and lying in official reports as ‘rule bending' even though these were clear examples of rule breaking. Our conceptualization of rule bending proposes a more nuanced view, one involving partial deviation from the requirements of rules. In order to fully understand employee rule following in organizations, we can view rule following behaviour on a continuum with following rules to the letter on one end, and completely breaking the rules on the other. In our study, many of employees' reactions to rules would have fallen somewhere in between these two extremes. We suspect rule following behaviour in many contemporary organizations includes much more rule bending than has been previously acknowledged.

Rule bending is precipitated by tensions between rules and other expectations, but how might employees try to bend the rules in ways that ease these tensions? To answer this question, we reflect on one of the behaviours we observed: selective disclosure, which involved employees sharing some aspects of CI but not others. By selectively disclosing, employees were attempting to serve both the purpose of the CI rule (keeping vulnerable knowledge away from outsiders) and the purpose of sharing the information (serving customers or facilitating knowledge-sharing with outsiders). Thus, it was rule bending that was initially motivated by the goal of satisfying competing self-regulatory influences. Further, employees' decisions about how to bend the rules involved assessments of risk, both personally and for the company. When selectively disclosing, employees would try to minimize personal risk by sharing information that could have been obtained from other sources, so that if the disclosure was discovered it would not automatically be traced back to them. In addition, they would try to minimize the risk to their company. Information that they felt could be disclosed with little risk, such as information lacking quantitative details, was more apt to be disclosed. The latter finding can be connected to Guo's (2013) framework of security related behaviours, where he distinguished between security risk-taking behaviour (a bad result might occur) and security damaging behaviour (a bad result will almost certainly occur). We learned of only one instance where an employee engaged in behaviour that seemed certain to damage the company: the episode of rule breaking at Technical that prompted substantial rule changes. Thus, we suspect that the types of rule bending we observed here, where employees attempt to minimize both personal and organizational risk, are common in organizations.

Rule Following and CI Protection

Finally, our findings have implications for the growing number of scholars who are interested in how organizations can protect their knowledge and CI (Dufresne and Hoffstein, 2008; Hannah, 2005; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen and Puumalainen, 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Liebeskind, 1996). Our findings suggest that employees bend or break rules that are designed to protect CI because they experience tension between those rules and other expectations they face. Employees tend to respond to that tension in the way that they think is best, not just for themselves and their personal interests, but also for their employing organizations. We found that our participants might leak CI to outsiders because of admirable motives: facing situations where they know they are breaking rules, and there is a possibility of being punished for doing so, they break the rules anyway because they believe that is the best way they can serve their employers. Further, employees who believe that leaking CI is the best course of action for their employers might often be correct. A salesperson who discloses CI to a client may make a big sale, and an engineer who shares CI with a colleague at another firm may get information that improves a product's design. Our findings suggest the need for a more nuanced view of CI leakage, one that acknowledges that it may arise out of admirable motives, and it may even benefit organizations.

Limitations

As with other qualitative research, our insights into rule following raise the question of generalizability, concerning the extent to which our findings apply to other organizations. Since our goal was to create and elaborate theory on rule following, more research is needed in order to confirm whether the ideas we have introduced hold when subjected to quantitative inquiry, and whether they are generalizable to other settings. However, we can speculate about contextual factors that may shape the extent to which our ideas will be applicable to other types of rule following in other contexts. We suggest that a key factor is the degree of intra-firm causal ambiguity about the importance of the subject matter to which a rule pertains. Intra-firm causal ambiguity exists when the relationship between a competency and an organization's competitive advantage is unclear or poorly understood in the minds of the firm's managers (King, 2007). In the two organizations we studied, there was a lack of consensus about whether it was more important to protect information as CI or to share it with others, perhaps because both organizations were still relatively young, and their understanding of how their technologies would yield competitive advantages was still evolving. Thus, while there was consensus within the organizations that CI was critical to their survival, there was significant causal ambiguity with respect to how it was critical. In other organizations, where the vast majority of employees believe that the protection of certain CI is critically important, employees might be more likely to tolerate tension-provoking rules because they have a clear understanding of why the CI needs to be protected.

We also appreciate that the data we collected through interviews is likely to have been influenced by our presence in the setting, and that our analysis of the data will be shaped by our own perceptions and experiences (Bluhm et al., 2011). While some have argued that objectivity may not be possible or even desirable in the case of qualitative research (Glesne and Peshkin, 1992), we undertook steps to ensure that our findings and the theory built from them would be credible. First, we were attentive to what the participants had to say and aimed to represent their voices as accurately as possible (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). We did not start the research expecting to learn about so many instances of rule breaking and bending, and we believe that our participants' willingness to share this information with us is evidence of their comfort in the interview setting and forthrightness in answering questions. We were also conscious of searching for disconfirming evidence during the data analysis process in order to enhance the validity of our conclusions (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). We deliberately included many direct quotes throughout our findings and provided context around them in order to allow readers to assess the credibility of our interpretations and, if they choose, to develop their own interpretations of the data.

Practical Implications

Our results have a number of practical implications for organizations. We have found that rules can come into conflict with other workplace expectations, and this creates tension that employees seek to resolve, sometimes by breaking or bending those rules in order to satisfy those other expectations. When developing rules, organizations should ensure that they are minimally disruptive to other rules and the other expectations employees face. In circumstances where disruptiveness cannot be avoided, management should clearly communicate the importance of the rules and the negative consequences for the organization that can occur if employees do not comply with them. This will increase employees' perceptions of the justifiability of the rules, making them more willing to tolerate the tension that they create.