The impact of transition programmes on workplace bullying, violence, stress and resilience for students and new graduate nurses: A scoping review

Abstract

Aims and Objectives

This scoping review aims to identify whether transition programmes support new graduate nurses and nursing students in terms of dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress and enhance new graduate nurses' resilience during the transition from education to clinical practice.

Background

Many new graduate nurses in their first year of employment experience issues at work such as violence, bullying and stress, which forces them to leave their jobs. Nursing students also experienced these issues during their clinical rotation. However, some hospitals and universities have developed transition programmes to help nursing students and new graduate nurses and ease their transition from education to clinical practice. Although transition programmes have been successful in increasing the retention rate for new graduate nurses, their impact on supporting new graduate nurses and nursing students in dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress and in enhancing their resilience is unknown.

Design

A scoping review of the current literature (with no date limit) using the PRISMA-ScR checklist for reporting scoping reviews was utilised.

Method

Following the scoping review framework of Arksey and O'Malley, a broad search (with no date limit) was performed in CINAHL, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, ASSIA, PsycINFO, Embase, PROSPERO and ProQuest Dissertation databases. Reference lists of the included studies were searched.

Results

This review found that most transition programmes provide support for new graduate nurses when dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress. Transition programmes varied in length, content and implementation. Preceptors' support, educational sessions and safe work environments are the most beneficial elements of transition programmes for supporting new graduate nurses. Education sessions about resilience provide new graduate nurses with knowledge about how to deal and cope with stressful situations in the work environment. We found no studies that focused on nursing students.

Conclusion

The paucity of research on transition programmes' impact on workplace violence and bullying means that further research is recommended. This to determine which strategies support nursing students and new graduate nurses in clinical practice and to explore the effect of these programmes on experiences of workplace violence and bullying.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Evidence indicates that there is a worldwide gap in how universities and colleges prepare nursing students for transitioning from the education system to clinical practice. New graduate nurses and nurse managers regularly report that their education did not fully provide them with the skills required for their transition to clinical practice. Transition programmes support new graduate nurses to deal with workplace violence and bullying and need to have structured implementation. Ongoing evaluation is required to ensure that the programmes meet the needs of nursing students and new graduate nurses and health organisations, improve new graduate nurses' transition to clinical practice safely, enhance their resilience to overcome issues in the workplace (such as violence, bullying and stress) and reduce their turnover.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global community?

- The majority of new graduate nurses experienced violence, bullying (by different predators such as senior staff and physicians) and stress at work environments whether they enrolled in the transition programmes or not.

- Transition programmes significantly supported new graduate nurses and eased their transition but did not reduce violence, bullying and stress, and no study focused on nursing students. However, some transition programmes positively impact on new graduate nurses who experience violence, bullying and stress based on the type of support that they provide to new graduate nurses.

- There is a need for transition programmes to provide support for nursing students and new graduate nurses during the experience of workplace violence and bullying, to enhance their resilience and ease their transition into clinical practice.

- A less stressful work environment, type of education sessions (such as coping and dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress management) and preceptors' support might influence the impact of transition programmes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Global nursing shortages are well-documented and expected to rise. It is predicted that by 2025, over a million expert registered nurses will retire, and as a result, these vacancies may be filled by new graduate nurses (NGNs; Owens, 2018). Despite the need for NGNs to resolve this shortage, the turnover rate among this group of nurses continues to be a global issue (Wise, 2019). According to the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), NGNs are defined as those who have between 0–24 months of work/clinical experience (RCN, 2007). This definition indicates that during the transition to clinical practice, NGNs need to be equipped with the required knowledge, cognitive abilities and skills to provide safe care for patients and to keep up with the practice environment (RCN, 2007).

Workplace violence can be referred to as abusive or aggressive behaviour that takes place within a work environment (Mellor et al., 2017). Bullying generally refers to “persistent exposure to interpersonal aggression and mistreatment from colleagues, superiors, or subordinates” (Einarsen et al., 2009, p. 44), where an employee experiences adverse behaviour, such as threats. The definitions of violence and bullying varied substantially, and other synonyms include hostility, incivility, threats and verbal abuse (Gillespie et al., 2017).

It is known that NGNs and final-year nursing students experience some challenges such as occupational stress, workplace violence and bullying while adjusting to their new roles and transitioning to clinical practice (Laschinger & Grau, 2012; Thomas, 2010). This can be due to their lack of clinical knowledge and self-confidence, as well as having to deal with issues such as high patient numbers, nursing shortages, complex patient care and the lack of sufficient support (Krut, 2018). These issues raise concerns among healthcare organisations about the ability of NGNs to deliver high-quality care for their patients (Laschinger & Grau, 2012).

Transition programmes (TPs) were developed to support and ease the transition of nursing students and NGNs from education to clinical practice and are recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011) in the United States, Australia (Health, 2020), United Kingdom (Tucker et al., 2019) and Sweden (Gellerstedt et al., 2019). This scoping review explores current TPs for student nurses and NGNs to inform future research that might support the transition of NGNs to clinical practice when dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress, enhance their resilience and improve their turnover.

2 BACKGROUND

Nursing has the highest rate of violence and bullying in comparison with other professions, and evidence suggests that NGNs and nursing students are more vulnerable to bullying and violence within nursing (Rittenmeyer et al., 2013). Lack of support from colleagues, preceptors and managers can subject NGNs to bullying, violence, job dissatisfaction and stress, leading to them leaving within the first year of employment and an overall increase in NGNs' turnover rate (Lalonde & McGillis Hall, 2017). The cost of turnover in the United States, Canada and Scotland ranged from $10,000–$88,000 per NGN, according to a systematic review by Li and Jones (2013). NGNs need support to enhance their resilience to cope with workplace violence and bullying. Resilience is defined as the ability to cope well with the changes and adversity in the work environment, and the term thriving is also related to resilience (Mcdonald et al., 2016). Although resilience is the ability to cope with changes and adversity, thriving is the ability to emerge from these changes stronger than before (Vera et al., 2020).

Evidence indicates that there is a worldwide gap in how nursing students are prepared for the transition from the education to clinical practice (Wolff et al., 2010). NGNs regularly report that when they were nursing students, their education did not fully provide them with the skills required for their transition, and nursing managers confirmed this issue (Little et al., 2013). To close this gap, the IOM in the United States recommended the establishment of TPs to start with final-year nursing students or NGNs. These programmes differ in the theories used, framework, structure, length, title and names (such as nurse residency programmes and internship programmes). However, all serve the same purpose of closing the gap between theory and the demands of clinical practice (More, 2017). A systematic review that included 177 individual studies about TPs (Reinhard, 2017) found that TPs are beneficial for NGNs' transition from education to clinical practice, although these programmes were varied in content, education training and period.

Transition programmes are orientation programmes that involve intensive lessons and practice relating to clinical skills, patient safety, evidence-based practice and leadership (Medas et al., 2015). They were developed to facilitate the transition of NGNs and nursing students into clinical practice and improve their retention by supporting them and developing their clinical and leadership skills. However, there was a lack of a clear structure and theories that underpin such programmes (Wise, 2019). Where there were theoretical underpinnings, the theories include transition theory (Duchscher, 2008) and the transition to practice model developed by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN, 2015).

Transition programmes have been effective in supporting NGNs and nursing students to develop their clinical, leadership and communication skills, improve patient safety and increase the retention rate for NGNs (Wise, 2019). They are also cost-effective for hospitals, as they reduce the turnover rate for first-year novice nurses (More, 2017). Nevertheless, the impact of these programmes on workplace violence, bullying and stress has not been reviewed and is yet to be identified.

A comprehensive mixed-methods systematic review of experiences of violence in the nursing profession shows that there is widespread workplace violence and bullying experienced by nursing students and NGNs (Rittenmeyer et al., 2013). There is evidence that undergraduate education for nursing students, such as sessions covering the topic of workplace violence and simulations, is beneficial to NGNs (Aebersold & Schoville, 2020). TPs can include education sessions and simulation, as well as support from a preceptor. However, it is unknown if these sessions effectively support NGNs during their transition to clinical practice in terms of dealing with workplace violence and bullying and enhance their resilience to cope with these situations. Additionally, there is evidence that medical residency programmes increased residents' awareness of the ways to deal with workplace bullying and violence (Ayyala et al., 2018). TPs appear to support nursing students and NGNs' transition and increase their retention and confidence. However, little is known about whether the TPs enable NGNs or nursing students to deal with and overcome workplace violence and bullying.

3 RATIONALE FOR THE SCOPING REVIEW

A scoping review was chosen over other review methods, such as a systematic review, to gain a broad understanding of the research on this topic, to initiate an academic discussion about the topic and to review the methodologies used within this area of nursing. A scoping review requires a reinterpretation of the literature without critically apprising the available studies (Levac et al., 2010). Arksey and O'Malley (2005) argue that a scoping review can work as a stand-alone project as it is a transparent and rigorous method for mapping the literature and for gaining a deeper understanding of the evidence, with the possibility of developing new understanding or the need for more focused inquiry from the evidence. A scoping review is useful to map a broad topic and emerging body of evidence. In the context of this article, the scoping review helps to provide an overview of TPs and their impact on workplace violence, bullying and stress among NGNs.

4 AIM

The aim was to fill a gap in the evidence and identify whether TPs support NGNs in dealing with workplace violence, bullying and stress and whether TPs enhance NGNs' resilience during the transition from education to clinical practice.

5 METHOD

The framework (five stages) of Arksey and O'Malley (2005), incorporated with that from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI; Peters et al., 2015), guided the methodology of this scoping review. The PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist (Tricco et al., 2018) was used to map the process of this review (see Appendix S1). The scoping review framework of Arksey and O'Malley involves (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting results. The five stages of Arksey and O'Malley with the JBI search steps scoping review methodology are described below.

5.1 Stage 1: Identify the research question

This scoping review is focused on TPs for NGNs and how they can ease their transition from education into the clinical practice setting by enhancing their resilience and supporting them to deal with workplace violence and bullying. The PICO (population, intervention, context/comparison and outcomes) mnemonic guided the development of the research question: How do TPs impact NGNs' ability to manage violence, bullying and stressful situation and enhance their resilience?

5.2 Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

5.2.1 Eligibility criteria

This scoping review aimed to identify the currently available evidence on TPs for NGNs, with a focus on outcomes relating to workplace violence, bullying, stress and resilience. Table 1 illustrates the inclusion criteria using PICO.

| PICO | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | NGNs (BSN or diploma licensed) with 0–24 months of work experience in any healthcare settings (academic or community) have finished their programmes and are enrolled in any type of TPs, regardless of the names of the TPs, their duration or content. | Studies that include nurses other than NGNs will be excluded. |

| Intervention |

TPs developed for NGNs and in colleges, universities, and healthcare settings (academic or community). All programmes that have been established to ease the transition of NGNs into practice (e.g., internship, mentorship, preceptorship, residency, transition and externship programmes). |

General hospital orientation programmes that encompass all newly employed nurses who have been hired in hospitals, whether they are NGNs or not, will be excluded. |

| Outcomes | The outcomes of the studies should be related to the transition of NGNs as well as their experience in bullying, violence, incivility, hostility, stress, conflicts, microaggressions and resilience during the enrolment into TPs. | Studies that include/compare NGNs with expert nurses or with other professions will be excluded. |

- Abbreviations: BSN, Bachelor of Science in Nursing; NGNs, new graduate nurses; PICO, population, intervention, context/comparison and outcomes; TPs, transition programmes.

The search strategy involved three steps, as guided by JBI (2014):

Initial search and developing keywords

To identify the existing research papers and relevant keywords for the search strategy, initial searches were conducted using CINAHL and Medline and keywords from the review question: nurse transition programme, residency programme, new graduate nurses, nursing students, workplace violence, bullying, stress and resilience. Any further keywords identified were searched across all databases. This search strategy was agreed by the authors.

Database search

The next step was performed using keywords to broaden the search, to ensure that all relevant studies were found and to ensure a comprehensive search (JBI, 2014). Truncation was used to retrieve records that had different word endings of the same keyword, for example, nurs* to capture nursing, nurses, nurse and so forth. Keywords were combined using Boolean operators as appropriate (OR/AND). Database searching was undertaken using CINAHL, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, ASSIA, PsycINFO, Embase, PROSPERO and ProQuest Dissertation databases; these databases are recommended in education and healthcare searches (Relevo, 2012). This search was limited to studies published in English, and no date limits were set to ensure the most relevant studies were included. See Appendix A for Medline electronic database search.

Hand searching and reviewing reference lists

A manual search of the reference lists of included studies was conducted between February and March 2020. The purpose of this final stage check was to identify studies that may have been missed in the earlier searches. In addition, this process included a search for articles cited by the selected papers. This process identified one additional study.

5.3 Stage 3: Selecting studies

The PRISMA (Brook et al., 2019; McGowan et al., 2020) was used. Duplication of studies was checked and removed initially using a reference manager (EndNote X9). The titles and abstracts of the papers were screened against the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). In the case where a paper's relevance was unclear, the full text was retrieved and examined; studies that met the inclusion criteria (n = 19) were moved to the data extraction stage. In a scoping review, rigour is maintained by having a minimum of two reviewers performing paper selection (Peters et al., 2015). This process was conducted independently by three reviewers. On completion, the decisions of reviewers were compared, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

5.3.1 Filtration

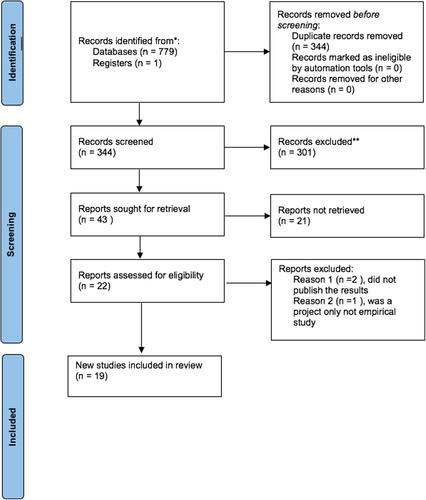

In total, 779 studies were found, and after removal of duplicates, 344 studies remained for potential inclusion. The titles of the remaining studies were reviewed to determine the studies that met the inclusion criteria, excluding a further 301 studies. The abstracts were examined for the remaining 43 studies, and 21 studies were removed. The full texts of the residual 22 studies were examined, three papers were removed, and 19 studies were included, as they met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 illustrates this process.

5.4 Stage 4: Charting the data

To minimise the risk of errors and to ensure data consistency from each study, the JBI data extraction form was used as a guide to extract data (Peters et al., 2015). Study characteristics (author, year, country, design [aim, method, sample and participants] and results) were extracted in the extraction form. Further information that was extracted from the included studies were the TPs' characteristics, NGNs reporting workplace bullying, violence and stress during the TPs and method in which the TPs support NGNs in dealing with these issues. One reviewer extracted the data from all included studies, and other reviewers provided feedback on the first five studies (see Table 2 for the data extraction results).

| Author, year and setting | Aim | Study design | Sample | Type and length of the programme | Programme characteristics | Data collection method and period | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ankers et al. (2018) Metropolitan hospital in Australia |

To explore the experiences of graduate nurses enrolled in a transition programme | Hermeneutic phenomenology | NGNs (n = 7) | Transition to professional practice programme, 1-year length |

Theoretical and clinical component Dedicated educators/support nurses Rotation in medical surgical or specialty units Programs designed to offer a supportive environment for NGNs by having educators/supportive nurses |

Semi-structured interviews First 4–8 months of the programme enrolment |

NGNs explained that transition to practice cause shock and can lead to negative emotions. NGNs report that they are struggling with the attitude of staff member; however, positive feeling was reported regarding the support NGNs gained from educators in the transition programme related to overwhelmed feeling and stress. |

|

Bratt et al. (2014) 25 hospitals in the United States |

To compare rural and urban NRP participants' job satisfaction performance and stress | Longitudinal cohort design |

Group 1 NGNs (n = 86) from 15 rural hospital Group 2 NGNs (n = 38) from 10 urban hospitals |

NRP, 1-year length |

Didactic (8 h) educational sessions Clinical orientation Evidence Based Practice (EBP) Simulation |

Job Stress Scale At the start of the programme, 6 and 12 months |

Rural residents had significantly higher job satisfaction score than urban residents (p = .03) and lower stress scale (p = .002). |

|

Chesak et al. (2019) Midwestern academic medical centre in the United States |

Assessed NGNs experience with stress management programme in the NRP | Descriptive qualitative | NGNs (n = 27) | NRP, 1 year |

SMART programme sessions about psychology Neurobiology of stress Resilience |

Focus group At Week 12 after completion, the sessions of the SMART programme |

The SMART programme within the NRP was helpful in decreasing stress by providing the opportunity to discuss stressful situations with other nurses, which helped NGNs to response more effectively to stressful situations. NGNs reported that they become more aware of the negative rumination and set a positive tone for their interactions. |

|

Cline et al. (2017) National Cancer Institutional USA |

To present the outcomes of internally developed NRP | Descriptive retrospective study | NGNs (n = 1638) | NRP, 1 year |

Didactic (8 h) education day once a month Clinical orientation EBP Simulation Reflection Oncology specific content |

Casey-Fink Graduate Nurse Experience Survey (CFGNES) Pre and post the programme enrolment |

Stress approached significant difference (p = .05) upport and satisfaction show statistically significant decline; mean score for support decreased from 3.36–3.29 (p = .002) and for satisfaction from 3.53–3.41 (p ≤ .001). |

|

Cubit and Ryan (2011) Non-profit hospital in Australia |

Exploring the experience of NGNs in graduate nurses programme | Survey + qualitative design | NGNs (n = 17) | Graduate nurse programme, 1 year |

3-day hospital orientation Four rotations and allocation with preceptors Support was provided by nurse coordinators Six study days across the 12-month programme Focus on team building exercises Frequent round by coordinators to gather information about NGNs and use this information to manage problems before they escalated |

Survey developed by nurse coordinators (n = 16) Focus group (n = 6) Collection period not reported |

NGNs continue to experience stress and anxiety during their first year as a result of increasing their responsibility. Coordinators round during the programme; debriefing with nurse coordinators and each other was a way of support NGNs received during stress experience. NGNs reported that assigning them with multiple preceptors was difficult for them where they experience preceptors who were unwilling to teach them. |

|

Dames (2019) One hospital in British Columbia |

To gain an understanding of the impact of the interplay between workplace and developmental factors that enable and disable thriving within the first year of nursing practice | Qualitative study | NGNs (n = 8) | Mentorship length not reported | Not described |

Semi structured interview Collection period not reported |

Participants experience hostility and bullying and felt powerless to challenge these issues. Some participants reported that the mentorship programme empowered them to address hostility behaviours as their mentor advocates for them, and they felt safe. |

|

Fink et al. (2008) 12 academic hospitals sites in in Denver, United States |

To evaluate the NGNs response to NRPs | Qualitative/survey | NGNs (n = 1058) | NRP, 1 year |

Didactic Clinical orientation Simulation Feedback |

CFGNES (open-end questions) On hire, 6 and 12 months of the programme |

Participant reported that the NRP was supporting them, especially manager support, feedback and positive peer review. Some reported that the programme relived their anxiety. 42% of participants experience transition difficulties; they experience lack of respect, gossipy and grumpy staff from registered nurses and co-workers. Also, participants experience more difficulties without a preceptor support and their need for a resource person or mentor. |

|

Glynn et al.(2013) Community hospital in New England, United States |

To explore the expectations and experiences of nurses who completed the emergency department internship programme | Qualitative design | NGNs (n = 8) | Internship programme, 6 months |

16 weeks of classroom instruction NGNs assigned to nurse preceptors for 6 months Clinical nurse specialists taught didactic content for 4-h weekly sessions for NGNs to discuss any clinical concerns, issues and staff relations |

Structured interview, 11 open-end question At the end of the programme |

Participants reported that the programme was supporting them during their transition especially their preceptors who teach them how to care for themselves. Participants wished the programme to be longer. Participants reported that the balance between classroom and clinical practice in the programme was a key to ease the transition. Only one participant perceived hostility and antagonistic behaviours, and another one described not feeling supported. |

|

Goode et al. (2009) 26 academic medical centre hospitals in the United States |

Outcomes of first 12 sites that participated in the residency programme | Longitudinal quantitative study | NGNs (n = 1484) | NRP, 1 year |

Didactic Clinical orientation EBP Simulation |

CFGNES First day of residency programme, 6 and 12 months |

Stress scores declined at the end of the programme (mean 1.34–1.81–1.05, p = .014). Declined in job and professional satisfaction scores at 6 months and increased at the end (mean = 3.39 at 6 months and 3.41 at 12 months, p = .000) |

| Harrison and Ledbetter (2014) in three sites in the United States | To determine the first-year turnover of newly licensed registered nurses | Descriptive post-test study | Site A NGNs with NRP (n = 46), Site B NGNs with routing orientation programme (n = 57) and Site C NGNs in magnet hospital with orientation programme (n = 358) | NRP, 1 year |

Clinical orientation (16 h) Didactic (58 h; leadership, patient safety and professional role) Simulation Mentor assigned for full year |

CFGNES Data collected: 1-year post-hire |

No statistically significant difference in stress score (p = .89) Site A had the higher mean score (3.6) in professional satisfaction. Site A is the only site that had the lowest turnover rate (2%). |

|

Kowalski and Cross (2010) 2 Academic hospital in Las Vegas, United States |

Report preliminary findings regarding NGNs participating in a local NRP | Pre/post | NGNs (n = 55) | NRP, 1 year |

Three phases: 2-week clinical orientation 12 weeks working side by side with a preceptor who undergoes a hospital preceptor training Simulation Didactic (monthly resident development days for 8 hours; each includes peer support session, educational module and skill presentation) |

(1) CFGNES (2) Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Data collected: pre and post the programme enrolment |

Feeling threatened and challenged decreased over a period (p = .004). Overall anxiety decreased (n = 34 in the beginning of the programme to n = 14 at the end of the programme) but no statistical significance (p = .188). Support and satisfaction show no statistical significance (p = .115 and p = .445). |

|

Olson-Sitki et al. (2012) Magnet-designated regional medical centre–United States |

To determine the effect of nurse residency programme on the NGNs' experience, retention and satisfaction | Non-experimental repeated measures mixed-methods | NGNs (n = 50) | NRP, 1 year |

Three phases: New employee onboarding and central nursing orientation (1 week) unit based Orientation (3 months) and the nurse residency programme 4-h educational and networking days are offered twice each month. |

(1) CFGNES (2) Field notes At 6 and 12 months from the programme |

No statistical difference in job satisfaction and stress at 6 and 12 months NGNs reported that the programme helped them to share experience and feeling of fear and stress with each other. Some NGNs reported that some nurses staff do not respect NGNs. |

|

Ostini and Bonner (2014) Rural acute care hospital New South Wales in Australia |

To explore the experiences of NGNs in their transition to registered nurse role in rural context | Naturalist qualitative design | NGNs (n = 5) | New graduation programme, 1 year |

5-day structured hospital orientation Clinical skills revision policy and procedure Rotation in different wards for 3 months |

Semi structured interview At the end of the programme |

Rotational changes during the programme were found to be daunting involving anxiety and stress; however, this was for a short period after each move. Participants were supported by senior nursing staff and educators. Participants described the clinical nurse educators as a very important support when they experience difficulties or need assistance. Some participants reported disappointment about the availability of support from preceptors in some units as well as the mentor support. |

|

Pizzingrilli and Christensen (2015) Mental health hospital at Niagara Health System in Ottawa, Canada |

Evaluation of mental health NRP | Pre-post design | NGNs (n = 8) | Mental health residency programme, 12 weeks |

Didactic: 40-h classroom-based sessions integrated with clinical activities Clinical orientation sessions about violence risk and recovery and emergency response |

Knowledge test questionnaires developed by the programme educator Data collected: pre and post the programme enrolment |

Statistically significant improvement in NGNs' knowledge about risk of violence and dealing with aggressive patients (p < .05). |

|

Rush et al. (2014) 7 health authorities in British Columbia, Canada |

To examine the relationships between access to support workplace bullying and NGNs' transition within the context of transition programmes | Mixed methods |

IG NGNs enrolled in the transition programme (n = 142) CG NGNs did not enrol in the programme (n = 103) |

Transition programme, 1 year |

Two phases: Orientation phase (organisation) 4 h 1–4-day nursing department orientation 96–144 h of supernumerary shifts with preceptors Transition phase, periodic educational sessions 1–6 days ranging from 4–7.5 h Formal/informal pairing with a mentor |

CFGNES At 12 months of the programme start |

The prevalence of bullying was the same between the two groups (39%) in each, but programme participants had more access to support. Bullying and harassment was a statistically significant moderator (p = .01) of relationship between access to support for NGNs and their total transition score. Programme participants (81.3%) were able to access support most (52.1%) or all (29.2%) of the time, and only 54.5% of non-programme participant could access support most (41.6%) or all (12.9%) |

|

Sampson et al. (2019) Midwestern USA academic medical centre |

Evaluate the effect of MINDBODYSTRONG programme for NRP on mental health and job satisfaction of NGNs | RCT |

IG (n = 49) received MINDBODYSTRONG programme within the NRP. CG (n = 44) enrolled in NRP |

NRP integrated with MINDBODYSTRONG programme, 1 year |

IG received MINDBODYSTRONG 8 weekly sessions focus on (1) caring for mind, (2) caring for body and (3) skills building Stress problem-solving, dealing with emotions in healthy ways Coping strategies with stressful situation Effective communication CG received 8 weekly debriefing sessions involving discussions about challenging events and experiences during the past week |

(1) The Perceived Stress Scale (2) The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale At baseline and 6-month post-intervention |

IG scored significantly better in stress, anxiety and depression (p = .022, .02 and .004), respectively. |

|

Spector et al. (2015) 105 Hospitals in the United States |

Examining quality and safety, stress and job satisfaction in NGNs during transition to practice programme | Longitudinal randomised comparative study |

IG NGNs participated in transition programmes (n = 542) CG NGNs participated in routine hospital orientation programme (n = 461) |

Evidence-based transition programme 6 months with additional 6-month institutional support, 1 year |

Clinical orientation to global nursing procedures and policy and patient safety Competencies Simulation Team experience Mentoring Didactic Online modules: patient-centred care communication and teamwork EBP quality improvement and informatics Trained preceptors assigned to guide the NGNs for the first 6 months of the programme Feedback Reflection |

(1) Work stress tool At 6, 9 and 12 months after hiring |

Work stress increased from baseline to 6 months and then decreased at 12 months. There was a statistically significant decline in stress in the CG (p = .004) in all periods. Both groups were less satisfied at 6 and 9 months; CG remained the most satisfied group over time (p = .031). |

|

Thomson (2011) North Carolina, United States |

Compared the survey scores between associated and baccalaureate-prepared NGNs who participated in NRP | Descriptive retrospective comparison study |

IG = Bachelor degree NGNs (n = 42) CG = Associate degree NGNs (n = 42) Both enrolled in the programme |

NRP, 1 year |

Clinical orientation Simulation Didactic Mentor |

CFGNES At 6 and 12 months from hiring |

No statistically significant difference between group related stress and communication (p = .5099) There was statistically significant difference related satisfaction and feeling of support; CG score greater than IG score (p = .0053) |

|

Wildermuth et al. (2020) Midwestern college of nursing and affiliate hospital in the United States |

To explore the lived experiences of a cohort of nurses as students and NGNs during transition in NRP | Qualitative transcendental phenomenological study | NGNs (n = 15) |

NRP Length not reported |

Start from the last semester of nursing school and continues through entry into practice Students have extended pre-hire job offers in the practice area with a preceptor |

Interview At the end of the programme |

Participants report feeling of stress, scared and nervous and being assertive with experienced nurses. NRP is a theme of overwhelming support, and their preceptors provide a safe environment to them. NGNs feel supported by their preceptors and felt a sense of mutual trust. |

- Abbreviations: CG, comparison group; IG, intervention group; NGNs, new graduate nurses; NRP, nurse residency programme; SMART, Stress Management And Resiliency Training.

5.5 Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

To ensure consistency, the three steps described by Levac et al. (2010) were used to collect, summarise and report the results: analysing the data, reporting results and applying meaning to the results. The steps included generating a descriptive numerical summary analysis, involving the outcomes that were relevant to the review question and considering the meaning of the findings for future practice, policy and research. The frequency of each variable was calculated, and the relationship between the findings of the selected studies was explored using a tabulation method as advised by the JBI (Peters et al., 2015). For consistency and clarity, the JBI (2014) advise reporting the findings based on the outcomes from the review question because it is a common practice to demonstrate the results in a structured and a clear way. Therefore, the outcomes (workplace violence, bullying, stress and resilience) were described textually in the finding with a pattering chart for these key outcomes from each included studies adapted from Bradbury-Jones et al. (2021).

6 RESULTS

6.1 Study characteristics

Most of the studies (n = 13) were from the United States with three studies from Canada and three from Australia. The study designs were qualitative (n = 8), mixed methods (n = 2), descriptive retrospective (n = 3), longitudinal (n = 3), pretest post-test (n = 2) and randomised controlled trial (n = 1; see Table 2).

6.2 Setting and participants

The included studies were from a range of healthcare services including hospitals that were rural, urban, not-for-profit, profit and university status. Most of the studies reported the demographic data for their participants. All NGN participants had 2 years or less clinical work experience as nurses. There were no nursing students among the participants. Across the studies, participants were predominately female (80%–100%), and their ages ranged between 21–54 years old. The most common education level reported in all the studies was Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) and Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) Degree (; see Table 3 for the demographic data of the studies' participants).

| Study | Age | Sample | Female (%) | Male (%) | BSN (%) | ADN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankers et al. (2018) | 24–55 | n = 7 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bratt et al. (2014) | 29–33 | Rural group (n = 86) | 98 | 2 | 51.9 | 48 |

| Urban group (n = 382) | ||||||

| Chesak et al. (2019) | 21–25 | n = 23 | 99 | 1 | 100 | 0 |

| Cline et al. (2017) | 20–39 | n = 1118 | 91 | 9 | 97.1 | 2.9 |

| Cubit and Ryan (2011) | 23–53 | n = 16 | 99 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dames (2019) | 25–31 | n = 8 | 100 | 0 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Fink et al. (2008) | Average 26 | n = 434 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Goode et al. (2009) | Mean =25 | n = 655 | 90.8 | 9.2 | 27.2 | 30.1 |

| Glynn et al. (2013) | 24–54 | n = 8 | 100 | 0 | 98 | 2 |

| Harrison and Ledbetter (2014) | 26–27 | Site A (n = 46) with NRP | 88 | 12 | 74 | 25 |

| Site B (n = 57), with routing transition programme | ||||||

| Site C (n = 358), magnet hospital with orientation programme | ||||||

| Kowalski and Cross (2010) | 21–40 | n = 55 | 83 | 17 | 58.2 | 41.8 |

| Olson-Sitki et al. (2012) | 23–31 | n = 31 | 87 | 13 | 58 | 42 |

| Ostini and Bonner (2014) | 20–30 | n = 5 | 80 | 20 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Pizzingrilli and Christensen (2015) | 21–31 | n = 8 | 80 | 20 | 90 | 10 |

| Rush et al. (2014) | 25–30 | n = 245 | 90 | 10 | Not reported | Not reported |

| IG (n = 142) | ||||||

| CG (n = 103) | ||||||

| Sampson et al. (2019) | 21–24 | IG (n = 47) enrolled in the NRP + MINDBODYSTRONG programme | 83 | 17 | 86 | 14 |

| CG (n = 42) enrolled in the NRP | ||||||

| Spector et al. (2015) | 23–28 | IG participated in transition programmes (n = 542) | 91 | 11 | 44 | 49 |

| CG participated in routine hospital orientation programme (n = 461) | ||||||

| Thomason (2011) | 20–39 | IG (n = 42) BSN | 95.2 | 4.8 | 50 | 50 |

| CG (n = 42) ADN | ||||||

| Wildermuth et al. (2020) | Not reported | n = 9 NGNs | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

- Abbreviations: ADN, Associate Degree in Nursing; BSN, Bachelor of Science in Nursing; CG, comparison group; IG, intervention group; NGNs, new graduate nurses; NRP, nurse residency programme.

6.3 Programme characteristics

The studies reported on TPs had different time frames and names. However, all programmes were developed to ease the transition of NGNs into clinical practice. The majority were called nurse residency programmes (n = 12), with other programmes being referred to as TPs (n = 3), graduate nurse programmes (n = 2), internship programmes (n = 1) and mentorship programmes (n = 1). The length of the programmes covers a slightly different range. Most studies reported a 1-year programme (n = 16), with three studies reporting <1-year programmes: 6-month programme (Glynn & Sheila, 2013); 12-week programme (Pizzingrilli & Christensen, 2015); and one study did not report on the length of the programme (Wildermuth et al., 2020).

In three studies, the curricula of the TPs were developed by the University Health System Consortium/American Association of Colleges of Nursing (UHC/AACN) national post-baccalaureate nurse residency programme (Goode et al., 2009; Harrison & Ledbetter, 2014; Thomson, 2011). This programme was based on Benner's (1982) novice to expert model. In addition, an academic-practice partnership between universities and hospitals developed the TPs in six studies (Bratt et al., 2014; Goode et al., 2009; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Rush et al., 2014; Spector et al., 2015; Wildermuth et al., 2020). In the remaining studies, the programmes were developed by the workplace health organisations (hospitals).

The pedagogy of the education of the included studies' TPs varied slightly. All programmes involved the core elements: didactic/theory (presentation, classroom teaching and seminar) with simulation in some studies and clinical practice (rotation with preceptors/mentor guided and orientation). Most programmes had a curriculum, which included general orientation, patient safety, communication, leadership, evidence-based practice, competencies and professional development (Bratt et al., 2014; Cline et al., 2017; Friday et al., 2015; Harrison & Ledbetter, 2014; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Rush et al., 2014; Spector et al., 2015; Thomson, 2011). Two studies reported specific education sessions within the TPs: the MINDBODYSTRONG programme that works on creating opportunities for personal empowerment to decrease anxiety and stress (Sampson et al., 2019), and the SMART (Stress Management And Resiliency Training) programme, which provide strategies that influence the health of NGNs and decrease their stress (Chesak et al., 2019). Although the curricula and length varied, the purpose of these programmes is homogenous: to bridge the gap between academic preparation and clinical practice demands. These programmes aimed to support NGNs to develop clinical skills, integrate with the healthcare team, provide safe patient care and improve NGNs' confidence, job satisfaction and retention, with no focus on equipping the NGNs with skills to deal with workplace violence and bullying. However, only two studies provide education sessions about dealing with stress and one study about violence. Moreover, no programme was found in the included studies that focused on supporting or preparing nursing students.

6.4 Findings

See Table 4 for a pattering chart for the key outcomes from each included studies that was adapted from Bradbury-Jones et al. (2021).

| Study | Outcomes | Programme characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violence | Bullying | Stress | Resilience | Preceptor/mentor | Simulation | Clinical orientation | |

| Ankers et al. (2018) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Bratt et al. (2014) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Chesak et al. (2019) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Cline et al. (2017) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Cubit and Ryan (2011) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Dames (2019) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Fink et al. (2008) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Goode et al. (2009) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Glynn et al. (2013) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Harrison and Ledbetter (2014) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Kowalski and Cross (2010) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Olson-Sitki et al. (2012) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Ostini and Bonner (2014) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Pizzingrilli and Christensen (2015) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Rush et al. (2014) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Sampson et al. (2019) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Spector et al. (2015) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Thomson (2011) | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Wildermuth et al. (2020) | □ | □ | □ | ||||

6.5 Workplace violence and bullying

Only six studies reported workplace violence and bullying (Dames, 2019; Fink et al., 2008; Glynn et al., 2013; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Pizzingrilli & Christensen, 2015; Rush et al., 2014). These studies used different terms such as threatening, harassment, hostility and violence. NGNs appear to experience bullying and harassment despite those NGNs being enrolled in different TPs and different settings (Canada and the United States; Dames, 2019; Fink et al., 2008; Rush et al., 2014). However, NGNs in these studies reported that the programmes supported them, empowering them to address these issues by providing preceptors and managers' support and positive peer review. In the study by Glynn et al. (2013), one NGN, among eight participants, experienced hostility, and another NGN described not feeling supported. The rest of the participants in this study reported that the programme supported them during their transition, especially the preceptors who were their advocates and taught them how to care for themselves and be more assertive in the role during the experience of hostility. This included weekly debriefing with discussions about the NGNs' clinical issues and concerns. It was found that NGNs had more access to support during the TPs (Rush et al., 2014) and that the programme significantly decreased NGNs' feelings of being threatened (Kowalski & Cross, 2010). The programme components reported by the NGNs that provide support and enhance their ability to deal with workplace violence and bullying were education sessions about dealing with violence that involve education in how to deal with verbal and physical violence, along with knowledge about the risk of violence (Pizzingrilli & Christensen, 2015) and preceptor support (Kowalski & Cross, 2010).

6.6 Stress and resilience

Fourteen studies reported results relating to stress. Five studies indicated that the TPs had no statistically significant effect in reducing stress (Cline et al., 2017; Harrison & Ledbetter, 2014; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012; Spector et al., 2015; Thomson, 2011), whereas three found that TPs significantly decreased stress (Bratt et al., 2014; Goode et al., 2009; Sampson et al., 2019). Three studies (Goode et al., 2009; Harrison & Ledbetter, 2014; Thomson, 2011) used similar TP (UHC/AACN) but with differing results. Goode et al. (2009) found that the programme significantly reduced stress (p = .014) and increased support for NGNs (p = .001). Harrison and Ledbetter (2014) and Thomson (2011) studies examined the effectiveness of the same TP on NGNs using different education level or settings to determine the effect of this programme with no educational or environmental impact. Both found no significant results in terms of stress.

A stressful environment can influence the impact of the TPs on NGNs' transition to practice. Bratt et al. (2014) compared rural and urban NGNs, both enrolled in the same TP, and found that stress reduced in both groups, but rural NGNs had a lower stress score (p = .03). The study concluded that rural nurses worked in a less stressful environment, and the TP helped in reducing stress in both groups. This was supported by a study conducted by Cline et al. (2017) who reported on the 10-year outcomes of internally developed TPs. They found that stress score for NGNs who participated in TP approach significant difference (p = .050). Notably, NGNs in this study worked in oncology units, which are considered stressful environments. Sampson et al. (2019) included a MINDBODYSTRONG programme within the TP to teach the NGNs coping strategies to deal with stress and emotional health in seven hospitals and from different nursing units, such as cardiac, medical, surgical and mental health units. The teaching involved sessions about coping strategies, managing change, problem-solving, dealing with emotions in a healthy way, effective communication, physical activities, positive self-talk and managing stress. The results showed that the perceived stress among the MINDBODYSTRONG programme's group significantly improved in the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) compared with the NGNs who enrolled in the TP (p = .02).

Six qualitative studies (Ankers et al., 2018; Chesak et al., 2019; Cubit & Ryan, 2011; Olson-Sitki et al., 2012; Ostini & Bonner, 2014; Wildermuth et al., 2020) reported that their participants experienced stress and anxiety, with the programmes being seen a form of support for those feeling overwhelmed or stressed. The more helpful strategies within the TPs (according to the NGNs who participated) were debriefing with nurse coordinators, peer review, supportive preceptors, hands-on activities and sessions about coping and dealing with stressful situations (such as increasing responsibility, availability of support from preceptors, shortage of staff nurses, feeling of disapproval and patient demands).

Only two studies reported on resilience (Chesak et al., 2019; Dames, 2019). They found that resilience education and training within the TPs decreased stress, and NGNs reported that the resilience programme helped them to identify how they deal and cope with stressful situations in the work environment (such as heavy work load, new procedures, lacking knowledge about the unit environment and feeling of disrespect hostility and disapproved from colleagues) by teaching them some strategies. These strategies include communication skills, opportunities to discuss stressful situations with other nurses and learn how those nurses handled these stressful situations, how to apply compassion and gratitude in everyday life and how to form deeper relationship with patients. However, some NGNs reported that feelings of hostility and threat disabled them from thriving in their work environment.

7 DISCUSSION

This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the extant literature and identify the gaps in the support that TPs provide to NGNs to cope with workplace bullying, violence and stress and enhance their resilience. The small number of the included studies in this review reflects the dearth of evidence on how TPs can support NGNs to cope with workplace bullying, violence and stress and enhance their resilience. However, this scoping review found that in nearly all of the included studies, the TPs supported the NGNs' transition. The terms violence and bullying were used in the included studies along with other terms (hostility and threaten). We did not identify any programmes designed for final-year nursing students; all were for NGNs.

The NGNs experienced bullying, harassment and hostility, although they were enrolled in different TPs and settings. Among these studies, three reported positive results for TPs in supporting the NGNs during the experience of hostility, bullying and threatening situations, specifically the preceptor's support (Glynn et al., 2013; Kowalski & Cross, 2010; Rush et al., 2014). The programmes were 1 year in length, evidence-based and involved preceptors and simulation. To date, there have been no other scoping reviews that have evaluated the programmes' influence on bullying, violence and stress in the workplace. However, there is some evidence that support from managers and preceptors along with mentorship programme can improve the positive culture of the workplace environment for NGNs and reduced the potential for workplace issues such as disrespect, conflict and oppression (Latham et al., 2008). Dyess and Sherman (2009) confirmed these points and indicated support provision by preceptors and programme's educators through TPs, although NGNs reported frequent instances of violence. TPs support NGNs during their transition from education to clinical practice by enhancing their clinical skills, knowledge and confidence and by providing a structured curriculum using education sessions, simulation and preceptors, which resulted in improving the NGNs' socialisation and retention (Halfer & Benedetto, 2020; Mullings-Carter, 2018). Thus, this scoping review found that TPs have the potential to support NGNs, but they did not minimise the exposure to workplace bullying and violence. More research is needed to identify strategies that can help minimise workplace bullying and violence exposure, such as education sessions and simulation, that focus on reducing these issues.

To reduce violence and bullying, managers and administrators could ensure a safe/healthy workplace environment by offering managers and preceptors' support to NGNs. Support from managers and preceptors through TPs can reduce the potential for workplace violence and bullying and improve the positive culture of the workplace environment for NGNs (Pasila et al., 2017). Kramer et al. (2013) suggested that the transition period should not focus on adjusting the role but on the workplace environment, by placing NGNs in less stressful units and providing support from staff nurses and managers.

The majority of studies in this review found that TPs did not reduce stress among NGNs; only three studies found that TPs significantly reduced stress. In contrast to a quantitative systematic review by Edwards et al. (2011; which lacked statistical data) found that TPs reduced stress.

Educational level (ADN and BSN) could impact the results. In Thomson (2011), the diploma NGNs felt more supported than the bachelor NGNs, both enrolled in the TP. This might be attributed to the differences between the educational curricula for diploma and bachelor in colleges; diploma students are better prepared to assume a professional role (Licensure, 2018). It is therefore advised that educational preparation during TPs for diploma and bachelor students should differ, for example, in technical skills, such as operating intensive care unit equipment, which might better enhance NGNs' transition into clinical practice. It would be beneficial for this preparation to begin before ADN and BSN nurses commence their professional role.

Findings from this review indicate that the nature of the work environment could contribute to the stress level. In one study of NGNs working in an oncology department (considered to be a stressful unit), TPs were used for more than 10 years, and no significant reduction in stress was observed (Cline et al., 2017). This supports the findings reported in the systemic review conducted by Al-Karim and Parbudyal (2012), which recommended that NGNs should begin working on less stressful units. It might be beneficial to hire NGNs to work initially on less stressful units, such as those with least heavy workload and critically ill patients, along with supportive preceptors. Reducing or eliminating the environmental impact might help support the successful implementation of TPs.

Moreover, this review found that education sessions about violence, stress and resilience during the TPs improved the NGNs’ knowledge about dealing with violence (Pizzingrilli & Christensen, 2015), decreased stress (Sampson et al., 2019) and helped NGNs address and cope with stressful situations (Chesak et al., 2019). These findings are in line with the evidence reported in other studies. There were improvements in NGNs' knowledge about harassment and violence and strategies to deal with these situations after the implementation of educational sessions during the TPs (El-Ganzory et al., 2014; Maresca et al., 2015). DuBois and Zedreck Gonzalez (2018) found that 90% of the NGNs (n = 61) reported that resilience sessions within the TPs were helpful, and their stress scores decreased. Before starting their professional role, if TPs provide NGNs with resilience strategies and teach them how to deal with the workplace violence, bullying and stress that they might be exposed to in their work environment, it could be possible to determine the exact effect of these key strategies.

Most of the studies reviewed in this scoping review reported that from the perspective of NGNs, the support of preceptors and mentors was the strongest component of TPs. Preceptors were the most supportive in TPs; they advocated for NGNs in cases of harassment and bullying and taught them how to protect themselves and cope with stressful situations. Previous evidence echoes this review's finding. Bakon et al. (2018) conducted an integrative review of graduate nurses' TPs and found that support from preceptors and mentors was an essential strategy in TPs. This support eases the NGNs' transition into a practice environment culture. Mentors helped NGNs address their concerns and reduced their turnover rate (Chen & Lou, 2014). Although preceptors and mentors support NGNs, a few of the participants in this review reported not being supported by their preceptors. This might be due to the preceptors' workload and their lack of preparation. In their systematic review, Brook et al. (2019) recommended that structured training for preceptors is needed to ensure a successful preceptor/NGN relationship.

7.1 Strengths and limitations

This scoping review has some limitations. Due to time constraints, the grey literature search was only conducted on one database. Thus, publication bias may have occurred due to the omission of unpublished research. Furthermore, the included studies were written in English. The inclusion of studies in other languages would have imposed a time and monetary cost. However, a comprehensive search was undertaken in key databases using all relative keywords and truncation, and reference lists were reviewed to ensure a systematic and transparent search. No quality assessment was performed on the included studies (as scoping review do not require critical appraisal). Thus, this review did not identify low-quality studies. Instead, this scoping review dealt with studies that used a range of designs and methodologies; thus, its focus was to provide a comprehensive overview of the relevant literature, not present a standard of evidence.

The generalisability of this scoping review to another contexts is questionable, because the studies in this review were only from the United States, Canada and Australia, due to the fact that only English language publications were included. Other settings might have different TP strategies or have some key components that support the NGNs' ability to address and cope with workplace violence, bullying and stress.

7.2 Recommendations

Managers', preceptors' and mentors' support with safe work environments could enhance the successful implementation of TPs. In TPs, preceptors need to have the skills and time to guide the NGNs' clinical experience and support their transition. Moreover, educational sessions about workplace violence, bullying, stress and resilience within TPs might be needed for nursing students and NGNs. More research on TPs that support final-year nursing students is needed.

8 CONCLUSION

This scoping review is based on 19 studies that focused on the impact of TPs on workplace violence, bullying, stress and resilience among NGNs. Considering the paucity of the studies included in this scoping review, it is difficult to provide a firm conclusion. However, this scoping review found that TPs support NGNs when they experience violence, bullying and stress, and they ease their transition to clinical practice, although these programmes were not effective in preventing these issues. Even though it was difficult to determine the most effective TP strategies, support from preceptors and mentors and the type of educational sessions might be the key components in successful TPs.

Moreover, this review found that, with support, a less stressful work environment and good educational preparation, TPs are more effective in facilitating a successful and safe transition for NGNs. However, prior to drawing this conclusion, especially with the complexity of the healthcare environment and the nursing shortage, additional high-quality research is required to assist in providing beneficial and successful TPs that ease the transition of NGNs.

9 RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

Transition programmes might be beneficial to start before NGNs begin their professional role as registered nurses. The findings from this scoping review identified that NGNs experienced bullying, harassment and stress, and they required support and more resources to prepare them for their professional role in clinical practice. Education sessions about dealing with workplace violence and bullying and training for nursing students might be beneficial for supporting nursing NGNs in dealing with these issues. Little is known about the workplace violence experience of NGNs during the programme participation. Moreover, no study discussed the importance of starting TPs for nursing students that are completing their nursing studies and are on their way to becoming registered nurses. Therefore, the impact of TPs, such as internship programmes, which started before the NGNs assumed their role as registered nurses, needs to be investigated as well as the needs for those NGNs and their experience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the peer review team in Birmingham University. There is no financial assistance for this project.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: KA, CBJ, NH; development of the eligibility criteria: KA, CBJ, NH; data extraction criteria and the search strategy: KA; review approach design, data analysis and writing manuscript: KA; revisions to the scientific content of the manuscript: CBJ, NH. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

APPENDIX A

Example of the search strategy in Medline, Embase and PsycINFO databases.

| Searches | Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1 | Internship program.mp |

| 2 | Nurse residency program.mp. |

| 3 | Transition program*.mp. |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

| 5 | exp Students, Nursing/ |

| 6 | New graduate nurses.mp. |

| 7 | Graduate nurs*.mp. |

| 8 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

| 9 | exp Workplace Violence/ or exp Violence/ or exp Nursing Staff, Hospital/ or workplace violence*.mp. |

| 10 | Workplace bullying.mp. or exp Bullying/ |

| 11 | Hostility.mp. or exp Hostility/ |

| 12 | Incivility.mp. or exp Incivility/ or exp Nursing Staff, Hospital/ or exp Workplace/ |

| 13 | Conflicts.mp. |

| 14 | Microaggression.mp. |

| 15 | exp ‘Resilience’/ or exp Coping Behaviour/ or resilience.mp |

| 16 | 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

| 17 | 4 and 8 and 16 |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.