The significance of nursing home managers' leadership—longitudinal changes, characteristics and qualifications for perceived leadership, person-centredness and climate

Funding information

Vårdalstiftelsen, University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care, FORTE 2014-04016, Vr 2014-02715

Abstract

Aims and objectives

The aim was to explore changes in nursing home managers’ leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate comparing matched units in a five-year follow-up and to explore the significance of managers’ educational qualifications and the ownership of nursing homes for perceived leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate in the follow-up data.

Background

Leadership has been described as crucial for person-centred care and psychosocial climate even though longitudinal data are lacking. The significance of managerial leadership, its characteristics, managerial qualifications and ownership of nursing homes for perceived leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate also needs further exploration.

Design

Repeated cross-sectional study.

Methods

This study used valid and reliable measures of leadership, person-centred care, psychosocial climate and demographic variables collected from managers and staff n = 3605 in 2014 and n = 2985 in 2019. Descriptive and regression analyses were used. The STROBE checklist was used in reporting this study.

Results

Leadership was still positively significantly associated to person-centred care in a five-year follow-up, but no changes in strength were seen. Leadership was still positively significantly associated with psychosocial climate, with stronger associations at follow-up. Six leadership characteristics increased over time. It was also shown that a targeted education for nursing home managers was positively associated with person-centred care.

Conclusions

Leadership is still pivotal for person-centred care and psychosocial climate. Knowledge of nursing home managers’ leadership, characteristics and educational qualifications of significance for person-centred delivery provides important insights when striving to improve such services.

Relevance to clinical practice

The findings can be used for management and clinical practice development initiatives because it was shown that nursing home managers’ leadership is vital to person-centred care practices and improves the climate for both staff and residents in these environments.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

- The findings build on existing knowledge of managerial leadership for person-centred care and climate, and the longitudinal measurements are able to confirm existing knowledge to a large extent.

- A targeted education for nursing home managers seems beneficial for person-centred services, suggesting that educational initiatives may be a relevant way to improve clinical practices.

- The findings may provide guidance for leadership training and/or development initiatives for managerial leadership in nursing home care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nursing home managers have a pivotal leadership role because they are the intermediators between policy-level directions and everyday care delivery, influencing both care quality (Jeon et al., 2010; Jeon et al., 2010; Siegel et al., 2010) and work conditions among staff through their leadership (Backman, 2018; Orrung Wallin et al., 2015). Nursing home managers’ areas of responsibility are complex and multifaceted, and besides being responsible for care development, managing budgets, and handling staffing issues and day-to-day queries, they are also accountable for monitoring and maintaining standards of care (Backman et al., 2017, 2020; Castle & Decker, 2011; Jeon, Glasgow, et al., 2010; Siegel et al., 2010, 2012). Internationally, the demands on nursing home managers and their leadership have grown substantially in complexity and magnitude in recent years given the increasing number of residents with complex care needs and the cultural change movement towards person-centred care. In addition to this, various organisational characteristics such as ownership type, public versus private funding and regulators have emerged (Meagher & Szebehely, 2013), giving further complexity to the area.

This indicates that nursing home managers’ leadership role needs to develop and evolve in order to keep up with the growing needs of an ageing population under the prevailing circumstances. It has been shown that nursing homes led by managers/leaders with higher leadership qualifications have significantly better care quality (Castle et al., 2015; Trinkoff et al., 2015). Similar results were reported by Castle & Fogel, 2002; Rowland et al., 2009 showing that nursing homes with more qualified leaders have fewer deficiencies compared with nursing homes with less qualified leaders. Although it has been suggested for quite some time that increased educational preparation is needed to improve leadership in nursing homes (Castle & Engberg, 2006; Resnick et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2010), the low educational levels among nursing home managers have been pointed out as a concern in previous literature. Forbes-Thompson et al., (2006) questioned how well managers were prepared to meet the increasing challenges in their leadership roles after finding that the majority of nursing home managers did not even have a bachelor's degree. Similar concerns were advocated by the Swedish government in 2009 (prop. 2009/10:116) concluding that nursing home managers’ leadership skills and competences were insufficient to meet national goals for nursing home care. It was shown that 10% had no education above the upper-secondary level and 37% of nursing home managers had a two-year college education at most. A national leadership programme of 30 ECTS credits was therefore designed for managers in nursing home care, which took place between 2013 and 2015. The national leadership programme was based on the ethical norms and values that form the foundation of aged care, with the purpose of improving leadership skills among nursing home managers in Sweden (NBHW, 2016). Despite many dropouts (only 55% of managers finished the education, representing 20% of all managers in Swedish aged care), this education initiative was still considered successful. It was reported that the participants were satisfied with the course content, which was regarded to be relevant and useful for their profession (NBHW, 2016). From an international perspective, it has been suggested that more research is needed to identify essential qualifications and competencies to increase the capacity of nursing home managers in order to match the unique needs and increasing demands of aged care organisations (Jeon, Glasgow, et al., 2010; Siegel et al., 2010, 2012). It has been stated that research knowledge about managers’ competencies and qualifications have the potential to inform directions for future nursing home enrolments by setting these standards (Siegel et al., 2010, 2012).

Person-centred care is considered a gold standard care model, usually defined as an ethical, humanistic and holistic care based on respect for personhood, capability, subjectivity and agency of the residents (Edvardsson et al., 2008; McCormack & McCance, 2010). Previous research has shown that to establish such person-centred standards nursing home managers need to articulate a clear vision of person-centred care (Backman et al., 2020; Quasdorf & Bartholomeyczik, 2019; Rokstad et al., 2015), value interpersonal trustful relationships with staff, and communicate with respect and sensitivity (Backman et al., 2020; Chalfont & Hafford-Letchfield, 2010; Stein-Parbury et al., 2012). Enacting person-centred principles by being a role model as a manager and actively supporting and engaging in the care practice seems to be essential for person-centred care practices (Backman et al., 2020; Rokstad et al., 2015). As part of a person-centred environment, it also seems important as a nursing home manager to support a psychosocial climate in which staff feel valued and acknowledged and that encourages and allows innovative initiatives (Backman et al., 2016, 2020). Although several cross-sectional studies (Backman et al., 2016; Ree, 2020; Sjögren et al., 2017) have found significant relationships between leadership and person-centred care practices, how these relationships develop over time is unknown because no longitudinal studies have been performed on this topic. To date, several intervention studies have highlighted the importance of managerial leadership when striving towards more person-centred practices (Chenoweth et al., 2014; Rokstad et al., 2015; Stein-Parbury et al., 2012). Still, studies exploring managers’ educational qualifications of significance for leading and promoting person-centred care are sparse. In one such study, a leadership framework developed for managers served as a foundation in a leadership and management intervention programme (CLiAC). The intervention aimed to improve leaders’ effectiveness on the work environment, staff turnover and care quality in terms of person-centred care (Jeon et al., 2015). This intervention showed an impact on management support, leadership actions and behaviours but did not have a measurable effect on person-centred care. It was suggested that changes in terms of person-centred care are too complex to be affected by a leadership and management programme (Jeon et al., 2015). This can be interpreted to indicate that little is known about the educational qualifications of significance for person-centred provision among managers.

- To explore changes in associations and degree of nursing home managers’ leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate comparing matched units in a five-year follow-up from SWENIS I to SWENIS II.

- To explore changes in leadership characteristics comparing 24 leadership items in matched units in a five-year follow-up.

- To explore the significance of managerial educational qualifications and ownership of nursing homes for perceived leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate in SWENIS II.

2 METHOD

2.1 Design

The U-Age SWENIS initiated a longitudinal monitoring of care and health in Swedish nursing homes with a point prevalence measurement to be repeated every five years (Edvardsson et al., 2016). The first data collection was performed in 2013–2014 (T1), and the first follow-up (T2) was performed in 2018–2019. Data for this paper's analyses were drawn from both data collections. This study followed the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies (Supplementary File 1).

2.2 Sampling and data collection

Out of the 290 Swedish municipalities in total, 60 municipalities were randomly selected in SWENIS I. In SWENIS I (T1), 35 municipalities of the selected 60 agreed to participate. T1 contributed with data from 169 nursing homes. For SWENIS II (T2), 25 municipalities from baseline agreed to participate at follow-up. To reach the same number of invited municipalities to start with, another 35 municipalities were randomised for inclusion at T2. The final sample of T2 consisted of data from 43 municipalities (28 baseline and 15 new) contributing with organisational, manager and staff data from 190 nursing homes. Data in SWENIS were collected with a survey with three parts (part A, B and C) following the same procedure at baseline and at follow-up. The A-survey consisted of a self-reported staff measurements of demographic variables together with estimations of leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate. The B-survey consisted of resident measurements and was not part of this current study. The C-survey was completed by the manager at each nursing home and comprised leader and organisational characteristics about the nursing home.

First, the chief executive officer of each municipality was contacted, and consent was sought and obtained. Following this approval, the manager in each participating nursing home was invited by telephone. Information about the study was given both orally and by e-mail to the managers. After approval, the managers distributed questionnaires to the participating staff in each unit, and the staff completed the surveys during working hours. The survey contained information about the study, how to complete the form, and whom to contact whether questions arose. To safeguard confidentiality, the survey was anonymous, coded to unit level, and no personal identification of the participants was collected and the survey was returned in a sealed envelope. All participation was voluntary, and withdrawal was possible at any time. All direct care staff with permanent employment or long-term substitutes who worked day/evening shifts at the time of the data collection were invited to participate. For T1, the data collection was performed between November 2013 and September 2014, and no reminders were sent out. For T2, the data collection was performed during a six-month period between October 2018 and April 2019, and three reminders were sent out. For T1, a total of 5423 surveys were distributed and the final sample consisted of n = 3605 (response rate 66.5%), and for T2, a total of 5803 surveys were distributed and the final sample consisted of n = 2985 (response rate 52%). Of the 526 nursing homes units participating at baseline in T1, 181 (34%) participated at T2. The comparative analyses for the first and second research question were based on these 181 matched units (comparing A-data in units that participated in both baseline and follow-up), comprising 1253 participants in T1 and 1176 participants in T2. The analyses for the third aim were based on matched manager and staff data on T2 data only.

2.3 Study sample and context

A majority of the nursing homes in both samples were public, 93.5% at T1 and 85% at T2, while 6.5% at T1 and 15% at T2 had private providers. The number of beds in the participating nursing homes ranged from 7 to 128 (SD 41.1) (mean 38) at T1 and from 6 to 116 beds with a mean 40 (SD 18.4) (median 36) at T2. Participating units in both samples consisted of special care units for persons with dementia (31% at T1 and 32% at T2) and general units caring for older people (69% at T1 and 68% at T2). In Sweden, the nursing home managers hold the overall operational responsibility for the residential care, the direct care work force, and the care and work environment (Backman, 2018). Being a nursing home manager in Sweden does not require a specific formal education, but a majority of nursing home managers have a degree of social work or registered nursing (Backman et al., 2017). Registered nurses in Swedish nursing homes hold the responsibility for the nursing care, while enrolled nurses and nurse assistants are responsible for personal and social care to the residents (Backman, 2018) (for demographic data on staff and managers, see Table 1).

| Staff | SWENIS I | SWENIS II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| na (%) | m (SD) | nb (%) | m (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 46.6 (11.3) | 45.4 (12.3) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 167 (4.7) | 202 (6.8) | ||

| Women | 3401 (95.3) | 2770 (93.2) | ||

| Native language | ||||

| Swedish | 2313 (82.6) | |||

| Other | 487 (17.4) | |||

| Qualifications | ||||

| Registered nurses | 12 (0.3) | 24 (0.8) | ||

| Enrolled nurses | 2918 (82.5) | 2534 (85.5) | ||

| Nurse's assistants | 463 (13.1) | 296 (10.0) | ||

| No formal qualifications | 82 (2.3) | 72 (2.4) | ||

| Other education | 60 (1.7) | 37 (1.2) | ||

| Work shift | ||||

| Day shift | 80 (2.2) | 74 (2.5) | ||

| Day and evening | 3140 (88.2) | 2563 (85.9) | ||

| Day, evening, night shift | 318 (8.9) | 304 (10.2) | ||

| Years of experience in aged care | 17.9 (10.3) (10.3) | 17.2 (11.8) | ||

| Years of experience in this facility | 9.9 (8.0) | 9.6 (8.7) | ||

| Managers | nc (%) | m (SD) | nd (%) | m (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.6 (9.0) | 50.6 (9.9) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 17 (9.0) | 19 (8.9) | ||

| Women | 172 (91.0) | 195 (91.1) | ||

| Qualifications | ||||

| Human resource specialist | 8 (4.3) | 14 (6.5) | ||

| Registered nurses | 52 (27.7) | 54 (25.2) | ||

| Enrolled nurses | 17 (9.0) | 31 (14.5) | ||

| Social work | 90 (47.9) | 89 (41.6) | ||

| Other education | 21 (11.2) | 26 (12.1) | ||

| Years of experience as a manager | 11.0 (8.7) | 12.7 (9.0) | ||

| Years of experience in this facility fafafacilityfacility | 3.4 (3.4) | 4.6 (4.6) | ||

- a Does not always add up to 3605 in all variables due to missing items

- b Does not always add up to 2985 in all variables due to missing items

- c n does not always add up to 191 in all variables due to missing items

- d n does not always add up to 214 in all variables due to missing items

2.4 Instrumentation

The Leadership Behaviour Questionnaire© was used to measure leadership (Ekvall & Arvonen, 1994) and comprises 24 items formulated as statements about leadership behaviours, and higher scores indicate leadership that facilitates efficient service delivery (Ekvall & Arvonen, 1994). Staff were asked to rate their manager/leader on a six-point scale from 1, completely disagree, to 6, completely agree. A total score can be calculated with a range of 24–144 (Backman et al., 2016). The Leadership Behaviour Questionnaire was used as a unidimensional scale because a recent confirmatory factor analysis of the 24-item version suggested a unidimensional factor structure (Backman et al., 2016). The 24 items used in this study were items 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33 and 34, which have been described previously (Ekvall & Arvonen, 1991, 1994). The following four items were also part of the 24-item version of the instrument: (A1) My manager coaches and gives direct feedback; (A2) My manager handles conflict in a constructive way; (A3) My manager has ideas for change and development; and (A4) My manager stimulates learning and competence development. In a recent study, it was shown that the most significant items of highly rated leadership were Experiments with new ideas, Controls work closely, Relies on his/her subordinates, and Coaches and gives direct feedback followed by Handles conflicts in a constructive way (Backman et al., 2017). The 24-item questionnaire used in this study is described in Backman et al., (2017; Ekvall & Arvonen, 1991). Cronbach's α was 0.98 at both T1 and T2.

The Person-centred Care Assessment Tool (P-CAT) was used to measure person-centred care (Edvardsson et al., 2010; Sjogren et al., 2012). The P-CAT is a self-reported assessment scale that measures the extent to which staff perceive the provided care to be person-centred. The P-CAT consists of 13 items formulated as statements about the content of care and aspects of the environment and the organisation. A total score is calculated (range 13–65), and higher values indicate a higher degree of person-centred care. The Swedish version of the P-CAT has shown satisfactory estimates of reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.75) and construct validity in Swedish aged care (Sjogren et al., 2012). Cronbach's alpha for the total score was 0.77 at both T1 and T2.

The Person-centred Climate Questionnaire–Staff version (PCQ-S) was used to measure staff perceptions of the psychosocial climate of the unit (Edvardsson et al., 2009). The questionnaire consists of the three dimensions: a climate of Safety, Everydayness and Community. Total scores can range from 0 to 70, and higher scores indicate a more positive and supportive psychosocial climate. The PCQ-S has shown good estimates of reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.88) and construct validity (Edvardsson et al., 2009). Cronbach's alpha for the total score was α = 0.91 at T1 and α = 0.92 at T2.

2.5 Data analyses

SPSS statistics version 26 was used to analyse the data. Missing items in the scales were replaced with the mean value of the individual for the total scale (cf. Shrive et al., 2006). Up to three missing items were replaced in the Leadership Behaviour Questionnaire (10.1% at T1 and 10.4% at T2), whereas up to two missing items were replaced in the P-CAT (8% at T1 and 7.7% at T2) and up to two items were replaced in the PCQ (3.7% at T1 and 5.1% at T2). Cronbach's alpha estimation was used to explore the reliability of the included measures. p-Values of <.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The analyses were performed in several steps. First, sample characteristics were explored using descriptive statistics. Second, the relationships between leadership and person-centred care and psychosocial climate were assessed with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Due to the fact that individuals were correlated in units because staff rated their perception of practice within the unit, an exchangeable correlation structure was assumed and the parameters were thereby estimated by using generalised estimating equations (GEE). Third, two simple linear regression parameters were estimated with GEE using care unit as the subject variable and person-centred care and psychosocial climate as the dependent variables and with leadership used as the explanatory covariate. A scatterplot was made in order to visualise the linear regression analyses. Fourth, a multiple linear regression model with interaction terms was used to estimate the change in the relation between leadership and the outcome from T1 to T2. Fifth, a multiple linear regression was performed to estimate the change in relation between leadership and the outcome from T1 to T2 with GEE taking into account correlation in nursing homes with an exchangeable correlation matrix and adjusting for age, sex and education. Independent samples t tests were used to assess mean differences in leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate between T1 and T2 (follow-up). Independent samples t tests were used to assess mean differences in the 24 leadership items in the Leadership Behaviour Questionnaire, comparing T1 and T2. When reporting results from this analysis, threshold parameters from a previous study on T1 data (Backman et al., 2017) were included in Table 4. Threshold parameters on an item refer to the item's difficulty and represent the thresholds between the options in that specific item. The 6-point Likert scale in the Leadership Behaviour Questionnaire has five different thresholds, one threshold between every option in the item, and these thresholds were determined by item response theory analyses in a previous publication (Backman et al., 2017). Higher threshold values indicate higher difficulty in scoring high on that item (Hays et al., 2000; Scherbaum et al., 2006). It was assumed that the items with high levels of difficulty in endorsing threshold 5 (or receiving a score of 6) were those that particularly characterised highly rated leadership behaviours (cf. Backman et al., 2017). Finally, three multiple linear regression models were made to explore the significance of manager educational qualification in terms of degree of social work and nursing because these are the most common qualifications among managers in these contexts and to explore ownership of nursing homes for perceived leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate at T2.

3 RESULTS

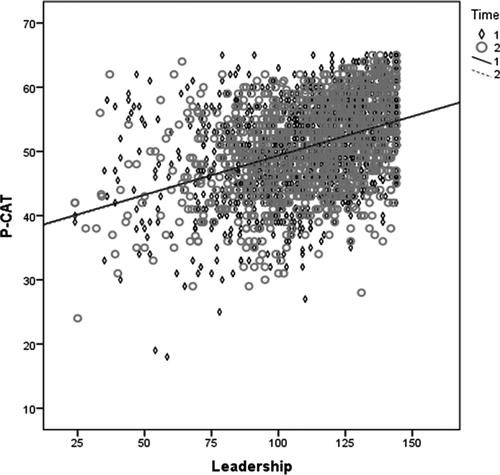

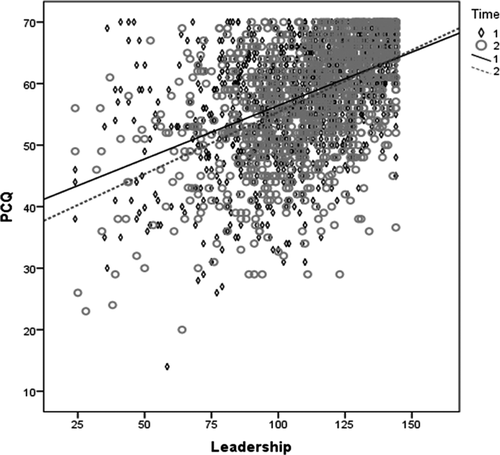

The correlation analyses between leadership and person-centred care showed a significant positive correlation at both T1 (r = .39, p ≤ .001) and T2 (r = .402, p ≤ .001). The same was true for the associations between leadership and psychosocial climate at T1 (r = .462, p ≤ .001) and T2 (r = .505, p ≤ .001) (Table 2). The results from linear regression estimating the change in relation between leadership and person-centred care between T1 and T2 showed no significant changes in the strength of association (∆β = 0.000, p = .974) (Figure 1, both regression lines are placed identically for T1 and T2). Linear regression estimating the change in relation between leadership and psychosocial climate between T1 to T2 showed a significant change in the strength of association (∆β = 0.028, p = .048), with a stronger association at T2 (Figure 2).

| Outcome | Independent variable: Leadership | Linear regressionc | GEEd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1b | T2b | ∆β (p-value) | ∆β (p-value) | ||

| PCQ | Correlationa | 0.462 | 0.505 | ||

| βc | 0.173 | 0.201 | 0.028 (.048) | 0.047 (.022) | |

| P-CAT | Correlationa | 0.390 | 0.402 | ||

| βc | 0.123 | 0.123 | 0.000 (.974) | 0.007 (.698) | |

- a Pearson correlation between Leadership and outcome.

- b All p-values <.001.

- c Results from multiple linear regression estimating the change in relation between Leadership and the outcome from T2 to T1.

- d Results from multiple linear regression estimating the change in relation between Leadership and the outcome from T2 to T1. The analysis is performed with generalised estimating equations (taking into account correlation in nursing homes with an exchangeable correlation matrix) and adjusting for age, sex and education.

The multiple linear regression with GEE estimated the change in relation between leadership and the outcome from T1 to T2 and confirmed the results from the linear regression analyses. No significant change in the strength of the association was found between leadership and person-centred care comparing T1 and T2 (∆β = 0.007, p = .698) (indicating that there were significant positive associations between leadership and person-centred care at T1 and at T2, and the strength of the association was consistent over time). The GEE also showed a significant change in association between leadership and psychosocial climate when comparing T1 and T2 (∆β = 0.047, p = .022), with a stronger association at T2 (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, no significant differences in degree of leadership (p = .084), person-centred care (p = .654) or psychosocial climate (p = .143) were found comparing T1 and T2 (Table 3).

| Data collection | N 1,2 | m (SD) | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | T1 | 1223 | 110.1 (23.5) | 0.084 |

| T2 | 1144 | 111.8 (23.1) | ||

| Person-centred care | T1 | 1237 | 50.5 (7.3) | 0.654 |

| T2 | 1158 | 50.7 (7.0) | ||

| Psychosocial climate | T1 | 1239 | 58.2 (8.9) | 0.143 |

| T2 | 1164 | 57.6 (9.3) |

- N¹ does not add up to 1253 in T1 due to missing items.

- N² does not add up to 1176 in T2 due to missing items.

Mean differences in leadership items are reported in Table 4. Six leadership items significantly increased between T1 and T2, including My manager: Handles conflicts in a constructive way (p = .006), Shows respect for others (p = .001), Controls work closely (p = .004), Stimulates learning and competence development (p = .004), Gives clear instructions (p = .02), and Coaches and gives direct feedback (p = .043) (Table 4).

| Item | My manager: | Mean T1 | Mean T2 | Mean differences | Sig | Threshold 5b, c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 | 3Handles conflicts in a constructive way | 4.081 | 4.238 | +0.158 | 0.006 | 1.56 |

| 34 | Shows respect for others | 4.847 | 5.003 | +0.156 | 0.001 | 0.68 |

| 24 | 3Controls work closely | 4.207 | 4.359 | +0.152 | 0.004 | 1.72 |

| A3 | Stimulates learning and competence development | 4.641 | 4.780 | +0.139 | 0.004 | 1.13 |

| 33 | Gives clear instructions | 4.567 | 4.684 | +0.117 | 0.020 | 1.04 |

| A1 | 3Coaches and gives direct feedback | 4.204 | 4.313 | +0.109 | 0.043 | 1.65 |

| 23 | 3Experiments with new ideas | 4.064 | 4.166 | +0.102 | 0.052 | 1.97 |

| 30 | 4.479 | 4.571 | +0.092 | 0.066 | 1.21 | |

| 27 | 4.642 | 4.713 | +0.077 | 0.149 | 1.04 | |

| 21 | 4.631 | 4.701 | +0.070 | 0.126 | 1.24 | |

| 12 | 4.894 | 4.963 | +0.069 | 0.115 | 0.83 | |

| 28 | 4.447 | 4.516 | +0.069 | 0.213 | 1.14 | |

| 19 | 4.723 | 4.787 | +0.064 | 0.199 | 0.90 | |

| 17 | 4.693 | 4.757 | +0.064 | 0.169 | 1.00 | |

| 8 | 4.811 | 4.873 | +0.062 | 0.175 | 0.94 | |

| 11 | 4.835 | 4.890 | +0.055 | 0.238 | 0.78 | |

| 5 | 4.395 | 4.446 | +0.051 | 0.365 | 1.33 | |

| 4 | 4.618 | 4.668 | +0.050 | 0.258 | 1,68 | |

| 18 | 4.728 | 4.773 | +0.045 | 0.357 | 0.87 | |

| A4 | 4.796 | 4.837 | +0.041 | 0.389 | 0.81 | |

| 6 | 4.731 | 4.765 | +0.034 | 0.488 | 0.97 | |

| 14 | 4.669 | 4.702 | +0.033 | 0.492 | 1.05 | |

| 31 | 4.814 | 4.824 | +0.010 | 0.824 | 1.06 | |

| 20 | 4.552 | 4.500 | −0.052 | 0.292 | 1.32 |

- a Due to copyright by ©Farax Group, not all 24 items are not reported in text. Please see Ekvall and Arvonen, (1994) for full scale.

- b Threshold 5 indicates high difficulty in scoring 6 on that item.

- c Highly rated leadership items reported in Backman et al., (2017). These were interpreted as representing the most important characteristics of highly rated leadership behaviours in nursing homes.

As reported in Table 5, managers’ educational qualification (in terms of registered nursing or degree in social work) was not significantly associated with perceived leadership (although it can be considered borderline significant) (p = .059) or with person-centred care (p = .682) or psychosocial climate (p = .776) at T2. Public nursing homes were significantly associated with higher degree of leadership (st β = 0.112, p ≤ .001). Having the National leadership education 30 ECTS credits as a manager was positively significantly related to a higher degree of person-centred care (st β = 0.061, p = .014). Finally, having other leadership education was negatively associated with perceived (lower degree of) leadership (st β = –0.131, p < .001), negatively associated with (lower degree of) person-centred care (st β = –0.065, p = .008) and negatively associated with (lower degree of) psychosocial climate (st β = –0.111), p ≤ .001) (Table 5).

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Person-centred care | Psychosocial climate | ||||

| St. β | p-value | St. β | p-value | St. β | p-value | |

|

Operation form public NH vs. private NH |

0.112 | <.001 | −0.035 | .136 | −0.030 | .204 |

|

Manager education Degree in reg. nursing vs. social work |

0.050 | .059 | 0.011 | .682 | 0.007 | .776 |

| National leadership education | −0.024 | .331 | 0.061 | .014 | 0.027 | .286 |

| Leadership education (other) | −0.131 | <.001 | −0.065 | .008 | −0.111 | <.001 |

| Adjusted R Square 0.030 Multivariate model | Adjusted R Square 0.015 Multivariate model | Adjusted R Square 0.011 Multivariate model | ||||

- a Models adjusted for manager gender, age and work experience in years.

4 DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was threefold, with the first research question exploring changes in nursing home managers’ leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate comparing matched units in a five-year follow-up between SWENIS I (T1) and SWENIS II (T2). The results did not show significant changes in the strength of association between leadership and person-centred care although highly significant associations were evident in both T1 and T2. This indicates that there were significant associations on both occasions and the strength of the associations remained consistent over time. Leadership has been considered to be an important driving force for person-centred practices in previous research (Chenoweth et al., 2014; Rokstad et al., 2015; Stein-Parbury et al., 2012), which these longitudinal measures in the current study provide support for. Person-centred care has been outlined as the gold standard care model in both the national and international literature, and it seems as the significance of leadership is of continuing importance. One possible explanation is that person-centred care has been described as multifaceted and as a holistic care model that requires a whole-system approach to be sustainable (Chenoweth et al., 2019; Edvardsson et al., 2014; Sjögren et al., 2017) and that it needs to be continuously facilitated, evaluated and refined into synchronised care actions by nursing home managers through their leadership in order not to fall back into institutionalised care (Backman et al., 2020). Seen in relation to this current study, it seems as the importance of leadership remains consistent over time, and although person-centred care has been recommended—and maybe even established—for some time, leadership support is still needed.

When comparing associations between leadership and psychosocial climate, the results showed significant changes in the strength of the association between leadership and psychosocial climate when comparing T1 and T2, with stronger associations at T2. This means that this study not only confirms the highly significant associations found at T1 (Backman et al., 2016), but also that the impact of leadership on psychosocial climate seems to increase over time, although the degree of leadership and psychosocial climate did not significantly change. The concept of climate refers to the holistic experience of the environment and involves an interplay between staff doing and being in the physical environment and the philosophy of care. It has been stated that the climate needs to support the personhood of residents in these environments (Edvardsson, 2008). The findings in current study imply that nursing home managers’ leadership has an increasingly significant role in setting the psychosocial tone of the environment.

Based on the second research question, exploring changes in leadership characteristics over five years showed that several items, my manager coaches and gives direct feedback, handles conflict in a constructive way, and controls the work closely, which were identified as characteristics’ of highly rated leadership in Backman et al., (2017), increased between T1 and T2. One possible interpretation is that, although the total score did not change significantly, the quality of leadership has improved because these items represent important leadership characteristics (cf. Backman et al., 2017) and this strengthens the relation between leadership and psychosocial climate. This current study shows that it is increasingly important to coach and give direct feedback, handle conflicts in a constructive way, and control the work as a manager (Table 4) as well as to support a psychosocial climate where staff are seen, acknowledged and valued (Table 2), and this confirms previous findings in this context (Backman et al., 2016, 2017, 2020). Because the psychosocial climate has been significantly associated with person-centred care provision (Sjögren et al., 2014) and with residents thriving in nursing homes (Björk et al., 2018), this gives further implications for nursing home managers’ leadership, suggesting that promoting a psychosocial climate may be an important precursor for place-related resident well-being and high-quality care. Also, positive associations have been found between the psychosocial climate and staff work satisfaction in the healthcare context (Lehuluante et al., 2012), and thus, it seems reasonable to assume that promoting a positive psychosocial climate may beneficially impact the staff work situation in several ways.

It was also shown that three further items—My manager stimulates learning and competence development, shows respect, and gives clear instructions—significantly increased over time. This can be related to McCormack et al., (2011) who found that creating an environment in which learning can flourish and where staff feel empowered and are offered personal and professional growth is a requirement for person-centred care. This gives implications for nursing home manager's leadership and suggests that learning and development initiatives may need to come from the manager in order to sustain and promote person-centred services. McCormack et al., (2011) also claim that person-centred values (such as respect) need to involve all persons engaged in the care, including staff and managers. This implies that having shared person-centred values is of significance for all persons involved and that managers are of utmost importance to demonstrate clarity on these issues, which is also supported by previous research (Backman et al., 2020; McCormack et al., 2015). Having a manager who gives clear instructions has been reported to be a facilitator when implementing person-centred care because integrating a person-centred philosophy into practice takes time and continuous support in order to challenge and change traditional care practices (Backman et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2016). One additional item reported as characteristic of highly rated leadership in a previous publication on this data (Backman et al., 2017) was borderline significant—My manager experiments with new ideas (p = .052). Although a p ≥ .05 is above the level of significance chosen, it has been suggested that there is a high likelihood that the true value is located close to the point estimate rather than close to the ends of the confidence interval, which is why this result does not necessarily need to be dismissed if it seems clinically meaningful (Hackshaw & Kirkwood, 2011). Because this finding resembles findings in previous research, a reasonable interpretation is that a manager who is innovative and experiments with new ideas also promotes person-centred care and psychosocial climate (Backman et al., 2016, 2020).

The third aim was to explore the significance of manager educational qualification and ownership of nursing homes on perceived leadership, person-centred care and psychosocial climate at T2. The findings showed that managers’ educational qualification (in terms of registered nursing or degree in social work) in relation to leadership was borderline significant (p = .059), with an advantage for registered nursing. This means that previously reported results in Backman et al., (2017), showing that a degree of social work as a manager was related to higher leadership ratings compared to managers with a registered nursing degree, was not confirmed. Managers’ educational qualification was not associated with person-centred care or with psychosocial climate. This indicates that there are other factors than managers’ basic education that influence person-centred care and psychosocial climate, and seen in relation to this study finding the characteristics of the nursing home managers’ leadership seem to be influential. Also, the results showed that having the National leadership education 30 ECTS credits as a manager seems to be important for the extent of person-centred care. This indicates that having a targeted education with a focus on ethical values and practices (such as person-centred care), systematic development work, and evidence-based practice may beneficially improve person-centred care. A systematic review has concluded that the whole organisation should promote a culture of shared ethical values in order to ease the transition to a more person-centred care practice (van Stenis et al., 2017), and thus, it seems reasonable to interpret this as meaning that the managers responsible for such changes also need to possess such ethical values. This suggests that the national leadership education initiated by the Swedish government in 2009 (prop. 2009/10:116) and Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW, 2016) has, at least to some extent, achieved its intended purpose of providing extended knowledge of how to lead person-centred practices.

Furthermore, the results showed that managers with ‘other leadership educations’ were related to lower leadership estimations. This can be interpreted to mean that the highly complex role and task of leading nursing home care do not benefit from general leadership courses, implying that more targeted leadership education may be more suitable in the area of nursing home care. Public nursing homes were significantly associated with a higher degree of leadership, which is contrary to previous (SWENIS I) findings (Backman et al., 2017). Previous research has showed that the results are mixed and inconclusive concerning differences between public and private providers (Winblad et al., 2017). Measuring the quality of long-term care has been described as a concern and key issue for policy makers around the world (Szebehely & Meagher, 2013). This study adds to the existing literature as no differences in person-centred care or psychosocial climate in relation to the nursing home's operational form was found. This indicates that other factors than operational form impact on the degree of person-centred care and climate.

4.1 Limitations

The repeated cross-sectional design of the study imposes some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. The small, but significant, change in relationship between leadership and climate may be due to differences in the samples rather than to a change brought about by the passage of time. However, although it is plausible that there were partly other individuals in the follow-up sample, the results indicate that there was a significant difference over time in these units, when controlling for the staff background variables, that is regardless of the characteristics of the included staff. This indicates that the importance of leadership has been strengthened regardless of sample characteristics, highlighting the increasing importance of leadership in those environments. Another limitation that comes with the cross-sectional design of the study is that all variables were collected at the same point in time, and thus, drawing inferences about cause and effects is impossible. However, because this study was part of a project with longitudinal measures, replicating the findings in a unique sample of matched nursing home units thus confirms the accuracy of the chosen analyses. The extent to which the results are generalisable beyond this context needs further studies.

5 CONCLUSION

Being the intermediator between policy-level directions and everyday care delivery as a manager is becoming increasingly important, and our results showed that leadership is still important and that certain leadership characteristics are still significant for person-centred practices and are increasingly important for psychosocial climate. The results indicate that the quality of leadership may have improved over time. It was also shown that a targeted education for nursing home managers was beneficially related to person-centred care. In practice, understanding nursing home managers’ leadership and educational qualifications of significance for person-centred delivery provides indispensable knowledge of what is required to lead on a daily basis and to improve such services.

6 RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The findings can be used for management and practice development initiatives in clinical practice because nursing home managers’ leadership may be vital to person-centred care practice and for improving the climate for both staff and residents in these environments. Understanding the educational qualifications that beneficially influence leadership performance has implications for recruitment procedures of leaders and managers in future nursing home care in order to clinically facilitate person-centred implementations. Such knowledge of what educations are necessary for person-centred practices can also inform educational initiatives among curriculums and academia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no existing conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors (AB, HL, ML, KS and DE) have participated in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and approved the final manuscript. AB contributed to data collection. AB, HL, ML, KS and DE drafted the manuscript or critically revised it for important intellectual content.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden (Dnr 2013-269-31, Ö 20-2018).