Culture, cognisance, capacity and capability: The interrelationship of individual and organisational factors in developing a research hospital

Abstract

Aim

To share our experience of implementing a programme of interventions aimed at building research capacity and capability of nurses and allied health professionals in a specialist children's hospital.

Background

Clinicians at the forefront of care are well positioned to lead on research to improve outcomes and experiences of patients but some professional groups continue to be underrepresented. Inequities persist alongside robust national infrastructures to support Clinical Academic Careers for non-medical health professionals, further highlighting the need to address local infrastructure and leadership to successfully build research capacity.

Design

An evolving programme of inquiry and analysis was established in one organisation, this included targeted interventions to mitigate barriers and enable research capacity and capability.

Methods

An all-staff survey was conducted in 2015 to understand the existing research culture. Interventions were put in place, evaluated through a second survey (2018), and focus group interviews with staff who had accessed interventions.

Results

Respondents demonstrated high levels of interest and commitment to research at the individual level which were not always harnessed at the organisational level. Inequities between professional groups existed in terms of training, time to undertake research and opportunities and outputs. Follow-up revealed continuing structural barriers at an organisational level, however at an individual level, interventions were reflected in >30 fellowship awards; major concerns were reported about sustaining these research ambitions.

Conclusions

Success in building a research-active clinical workforce is multifactorial and all professional groups report increasing challenges to undertake research alongside clinical responsibilities. Individuals report concerns about the depth and pace of cultural change to sustain Clinical Academic Careers and build a truly organisation-wide research hospital ethos to benefit patients.

Relevance to clinical practice

The achievements of individual nurses and allied health professionals indicate that with supportive infrastructure, capacity, cognisance and capability are not insurmountable barriers for determined clinicians. We use the standards for reporting organisational case studies to report our findings (Rodgers et al., 2016 Health Services and Delivery Research, 4 and 1).

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

- Our single hospital case study has illustrated how local and national need has shaped a programme of interventions to develop clinical academics.

- We have shown how a strategic approach to planning and delivery of interventions, underpinned by leadership, commitment and support, has resulted in significant success at the individual level.

- The achievements of individual nurses and allied health professionals indicate that with supportive infrastructure capacity, cognisance and capability are not insurmountable barriers for determined clinicians.

1 INTRODUCTION

Excellence in care is characterised by the use of research, with patients cared for in research-active institutions reportedly having better outcomes (Jonker & Fisher, 2018). Moreover, engagement in clinical research is associated with improved wider health care performance at an organisational level (Boaz et al., 2015), including increased organisational efficiency, improved staff satisfaction, reduced staff turnover, improved patient satisfaction and decreased mortality rates (Harding et al., 2016). It is these developments that have spurred the Care Quality Commission (CQC), a national body that inspects National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England, and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), the overarching organisation for management of clinical research in the United Kingdom (UK), to incorporate clinical research activity as an outcome measure in CQC inspections (Gee & Cooke, 2018). Thus, there is now greater recognition of the role of research in high-quality patient care and a process to strengthen the assessment of research activity, potentially signalling a new era for research in the NHS (Maben & King, 2019). However, questions continue to be asked about why NHS hospitals are not doing more research (Van't Hoff, 2019). Of course, the answer to this question is multifactorial (Dimova et al., 2018; Fletcher et al., 2020). There are some factors that have been consistently highlighted, at both organisational and individual levels, and underpinning all of these are culture, attitude, values and behaviours (Dimova et al., 2018). Understanding the context and culture of an organisation, and the professionals that work within it, are key to driving forward a research agenda, ensuring that those who wish to engage in research are enabled to do so.

2 BACKGROUND

A research-active workforce is important to the NHS: we need ‘to build the capacity and capability of our current and future workforce to embrace and actively engage with research and innovation’ (Health Education England, 2019). What is needed are innovative and varied programmes to build a critical mass of research-active staff across all professional groups, including strategies to sustain this cohort, referred to in the UK as clinical academics. We have a long tradition of pathways for medical doctors who choose to combine an academic role with clinical practice (Trusson et al., 2019), with an expectation of opportunities and well-established clinical and academic partnerships enabling these roles to flourish. Clinical academics comprise around 5% of the medical consultant workforce (Medical Schools Council, 2016). In contrast, the proportion of nurses is much less, with the current ambition to have 1% of midwives and allied health professionals (AHPs) as clinical academics in the workforce by 2030 (Baltruks & Callaghan, 2018).

In its 10-year report, the NIHR expressed concerns regarding an imbalance in progression of non-medical professionals, revealing poor academic advancement for nurses and AHPs (Morgan Jones et al., 2017). The steps taken to address this through a national infrastructure and networks supporting clinical academic pathways are well documented (Health Education England, 2018). National infrastructure, at the supra-organisational level, is not, however, enough. Healthcare systems, at the organisational level, need to invest and plan strategies to develop research capacity (Gee & Cooke, 2018), through local infrastructure and leadership (McCance et al., 2007; Richardson et al., 2019), a point noted almost 20 years ago by Rafferty and colleagues (Rafferty et al., 2003). Without local support, the development of successful funding or fellowship applications, or the ability to backfill posts prior to or after a successful award, are recognised as impossible (Cooke, 2005). The development of such structures is known to be complex and can be limited by the contextual challenges faced by organisations: what is needed are complex solutions to address complex and varied challenges in the NHS (Cooper et al., 2019).

2.1 Design

Building on a decade of a committed focus to foster clinical inquiry in our hospital, we share the infrastructure, processes and evaluation of our programme to date.

2.2 Aim

To share our experience of implementing a programme of interventions aimed at building research capacity and capability of nurses and AHPs into the research culture of a specialist children's hospital.

2.3 Our approach

- Understanding the existing research culture for healthcare workers (survey);

- Implementing a programme of interventions;

- Evaluating change at the organisation (repeat survey) and individual (focus groups) level.

We detail first the case and the context to our programme.

2.4 Case and setting

This programme of work was undertaken at a tertiary children's hospital. It provides care for children and young people with highly complex, rare or multiple conditions. The hospital has 383 patient beds, including 44 intensive care beds, with over 255,000 patient visits (inpatient admissions or outpatient appointments) annually, and carries out approximately 18,800 operations each year. Around 4100 staff work at the hospital, of whom 1500 are nurses and 268 are AHPs. It has the only UK NIHR funded Biomedical Research centre (BRC) dedicated to paediatric research, working in partnership with other institutions, as part of the largest cluster of child health research in Europe.

The programme of work took place over a 5-year period (2015–2020), following the creation of a part-time post, a Clinical Academic Programme Lead, funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) within the hospital. The post-holder was embedded in an established hospital-wide centre dedicated to patient-focused research by nurses and AHPs. A range of supportive strategies for nurses/AHPs were already in place within the centre, including a weekly drop-in clinic, annual study day and evening seminars.

The introduction of the Clinical Academic Programme Lead coincided with an organisation-wide ambition to transform from being a ‘hospital that does research’ to ‘a research hospital’; where research is fully integrated into every aspect of the hospital, and the development, conduct and translation of research are as much a foundation for all staff members’ professional activities as the delivery of high-quality, effective and compassionate clinical care and treatment. The programme of interventions led, and/or initiated by the Clinical Academic Programme Lead, were integrated into the existing research centre and implemented through a team approach involving the existing members of the senior management team.

2.5 Procedures and findings

To offer the best illustration of the content and nature of this evolving programme of work, we detail our actions, followed by findings and the learning, that then informed further actions. We use the standards for reporting organisational case studies to report our findings (Rodgers et al., 2016; (Appendix S1)). We began by examining the culture in our organisation.

2.6 Understanding the existing culture

2.6.1 What we did

- Part 1: nine questions focused on staff perceptions of their ability to support families to be involved in research within the hospital.

- Part 2: 22 questions focused on staff views concerning their engagement and involvement in research.

A free text box was available for comments. Staff were invited to provide contact details if they wanted to receive support with particular aspects of the research process. The survey was anonymised and distributed widely via the hospital all-users email, newsletter, intranet and screensaver, as well as hard copies being distributed to staff with the assistance of volunteers. Return of completed questionnaires was taken as consent to participate. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample, and chi-square, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare respondent groups. Where provided, comments were used to illustrate quantitative findings and reveal important factors not addressed in the survey questions. Data entry was undertaken by two researchers (KO and JW), with the addition of two further researchers for the analysis (FG and DS). A total of 629 (16% of the workforce) completed surveys were returned, with similar numbers of responses from nurses (n = 190, 30%), AHPs (n = 167, 27%) and ‘others’, this included staff working in administrative, support, non-clinical and research roles (n = 178, 29%). Fewer responses were returned by doctors (n = 85, 14%).

2.6.2 What we found

Key themes around capacity included research interest and awareness; research training and opportunities; research support and infrastructure; research activity and outputs; and research culture. The theme of ‘research culture’ was a consistent thread in the free text replies. Anonymised verbatim quotes are used for illustrative purposes, with the respondent's professional group provided where this information was available.

Culture

Research is key to the future of nursing … it doesn't get the profile it deserves.

It would be helpful if [hospital] could promote a more general understanding and awareness of research … to promote understanding that all research does not mean 'invasive testing' but can cover a wide range of involvement and can be a positive participation with benefits.

As an AHP I have been involved in many posters and have spoken at international conferences. The tight constraints on our clinical time is now meaning we are not able to complete a lot of this work and this is a great shame as there is so much expertise in our department.

I understand that as a healthcare scientist I am here to provide a service but with the unique nature of our patient cohorts it would be almost negligent not to gain information from their samples in addition to routine analysis. This involves going the extra mile.

I have held grants from the MRC and Wellcome Trust whilst working for the hospital, but ALL my research has been conducted with external collaborators. These collaborators contact me to join their grant proposals, as they would appear to appreciate my skill set. Sadly, one is never asked to assist a group here.

If there was more research awareness around the hospital and more resource available it would have such a positive impact on the rate of recruitment. It would also make the process so much easier for both staff and patients - resulting in an improved patient experience and aid retention of staff to research positions.

Cognisance

The majority of nurses, AHPs and doctors agreed that they understood research terminology (79%), knew how clinical practice is influenced by research (87%) and felt confident about using research in practice (70%): perhaps reflective of the nature of respondents who chose to complete the survey. Despite this, and the fact that the majority (73%) of respondents had had some involvement with research in the previous three years, awareness about research support available for staff in the hospital was generally limited, with approximately half of respondents not knowing who to contact to start a research project, only 29% of respondents feeling able to provide information to families about ongoing research, just over half (56%) knowing who to direct families to for this information or knowing where to access information, or what was meant by patient and public involvement (PPI).

Whilst staff awareness of research within their clinical area was considerably higher than at hospital level, only half of respondents felt they were regularly updated about what was happening in their individual clinical setting. In addition, there was variability across professional groups with significantly more doctors (70%) reporting being updated about studies than nurses (49%), AHPs (47%) or others (41%) (Kruskal–Wallis H = 22.27; p < .001).

Having been involved in recruitment for a research study I would like to see older patients, parents and public being generally more aware of research and to feel it to be a positive and integral part of care at this leading hospital.

Capacity and capability

Research is an important and fascinating part of the work we carry out and there is considerable pressure to participate and achieve in this domain. However, there is no protected time do so. I am only able to maintain my involvement in research by doing so in my own time and reducing the free time I have to spend with my family.

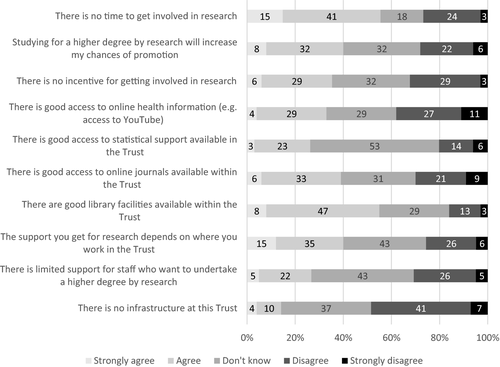

Views about research infrastructure varied, with many respondents indicating ‘don't know’ in response to statements about different sources of support available for staff who wish to engage in research (Figure 1). Overall, library facilities were viewed positively. However, a lower percentage of respondents agreed that access to online journals was good (Figure 1). Whilst some respondents had accessed research evidence to inform their clinical practice within the previous week (43%) or month (35%), nearly a quarter (22%) replied ‘never’ or ‘within the last year’, with some giving a clear message that accessing research evidence was problematic due to a lack of time or resources. There was a significant correlation between access to online journals/health information and respondents reports of confidence using research evidence to inform clinical practice (online journals: r = .113; p = .017; health information: r = .148; p = .002). There was general agreement that the support staff get for research depended on where they worked within the hospital.

There was a clear and statistically significant relationship between beliefs about the existence of infrastructure in the hospital and feelings of being able to access facilities, support and time to do research and the incentives available (r = .129 to. 546; p < .005). Perceptions of there being regular research meetings to explore ideas positively correlated with respondents feeling able to understand research terminology, feeling confident about research in practice and knowledgeable of how practice is influenced by research, as well as having opportunities to reflect on practice and having access to training and development opportunities (r = .235 to .513; p < .01). However, for nurses and AHPs, perceptions of there being regular research meetings were also associated with feeling pressurised by colleagues to undertake research (r = .266; p < .001).

In terms of research activity, there was a significant difference between professional groups in terms of having fulfilled a lead investigator (χ2 = 117.743; p < .001) or co-investigator (χ2 = 124.211; p < .001) role, with more doctors having been a lead investigator (36%) or co-investigator (42%) compared with AHPs (LI:10%, CI:10%) or nurses (LI:1.6%, CI:3%). Just over half of all respondents answered questions about presentations and publications. Few had published from their PhD (3.5%) or Masters (2%) compared to other research (22%). Whilst 70% of doctors had published research, this compared to only 31% for AHPs and 12% for nurses. For the 330 respondents who reported on conference presentations, there was also a significant difference between professional groups (χ2 = 85.289; p < .001), with 94% of doctors having presented at a conference compared with 69% of AHPs and 31% of nurses.

The survey results demonstrated high levels of interest and commitment to research at the individual level; however, this was not always harnessed at the organisational level to facilitate a culture of inquiry. The results indicated a level of inequity between professional groups regarding access to research training, time to undertake research and research opportunities and outputs. We found that awareness and cognisance of research was core to understanding perceptions of roles and contribution to research in our organisation. Moreover, as organisational culture has a role in promoting some behaviours and blocking others, it being shaped by established attitudes, values and practices, it was important for us to capture this. In our view, without these insights of how staff experience this interplay of relationships, progress on developing the multidisciplinary clinical research workforce to improve care and treatment for children and families will remain uneven across professional groups and clinical specialities.

2.7 Implementing a programme of interventions

2.7.1 What we did

We implemented an evolving programme of interventions (Table 1) aimed at enhancing the research culture to make undertaking research and developing a clinical academic career (CAC) pathway more attractive and accessible for nurses/AHPs, with the certainty that this would lead to better engagement and interest in research, thereby increasing research capacity and capability. The programme comprised a range of individual support, group workshops and networking opportunities, funded internships and the provision of resources, as well as mentorship and supervision. Some of these interventions (indicated in italics in Table 1) were initiated prior to conducting the staff survey in response to the national and local drive to support nurses and AHPs to embark on a CAC pathway. Other interventions were implemented in direct response to the survey and the evolving picture of what emerged as local need. In addition, we implemented a more responsive series of activities to increase staff awareness and engagement with research and access to research information, including a nursing/AHP research newsletter. We also took the opportunity to gather staff views on what a research hospital meant to them through a photobooth activity as part of an organisation-wide event on clinical trials day.

| What | Why | How | Resource | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funded doctoral internship | To build research capacity by facilitating nurses/AHP’s to develop and submit a competitive application for the NIHR CDRF | A formal programme of small group seminars built around 15 core objectives and delivered over an 8-month period; collaboration with research design service; peer review process; mock interviews; emotional and practical support; accompanying to NIHR interview | Funding to release interns from clinical duties 1 day/week for 8 −4 months and for patient and public Involvement activities or research training |

Internship's for CDRF 18 funded (10 nurses, 8 AHPs) Following competitive application process Internships for PCAF 1 funded (1 AHPs) Total PCAF awards 5 AHPs, 1 nurse |

| Evening seminars | To build research capability, drawing upon local and national experts, increasing exposure to a range of research methodologies | Delivered around a networking event, methodological and content expertise, for example art-based research, poetry in research | 20017–8 4 sessions |

>160 20–60 per session |

| Workshops | To build research capacity by facilitating nurses/AHPs to develop and submit a competitive application for the NIHR/HEE funded Pre-MRes and MRes Fellowships | Monthly workshops taking nurses/AHPs through the application process, including what makes a good research CV and how to develop a good research question | Four x 1-hour group workshops with additional individual sessions as required | 25 MRes applicants |

| Annual conference | To build research capability and capacity, by providing a vehicle to show-case NAHP research in the organisation | One-day conference, in-house, oral and poster presentations from PhD students, and others, guest speakers, followed by networking session | 2015–2018 |

>150 40–50 participants per event |

| Academic inquiring minds forum | To build research capability and facilitate nurses/AHPs to network internally; sharing ideas and engaging in critical debate | Monthly programme of taught research seminars and discussion | 1.5-hour monthly sessions conducted over lunchtime with lunch provided |

>80 registered members Seminar attendance 10–40 per session. |

| Residential training weekend |

To build research capability and facilitate nurses/AHPs to network externally; sharing ideas and engaging in critical debate Expanded to include additional professional groups across a region |

Two-day programme of workshops, taught seminars, and social activities for NAHPs | 2-day weekend training event at an external venue with external speakers, accommodation and catering |

Own staff 17 External 10 |

| Mentorship and Supervision | To build research capability through provision of mentorship and/or academic supervision |

Supervision of students on academic research programmes (MRes, PCAF and PhD) Formal mentoring of students on NIHR fellowships Provision of mentorship training |

Weekly-monthly meetings |

Doctoral Supervision provided from the research centre to 6 nurses, 3 AHPs Mentorship participation has extended to include those at earlier stages on the CAC Pathway mentoring PCAF awardees, 4 AHPs and 1 nurse |

| Funded Post-Doctoral Internship | To build research capacity by facilitating nurses/AHPs to develop and submit a competitive application for a post-doctoral fellowship or research grant following completion of their PhD. | Individual support and mentorship | Funds to release interns from clinical duties 1 day/week for 6–4 months and for a conference presentation or research training | 7 internships funded (1 nurse, 3 AHPs, 3 psychologists) |

| Funded Development Internship | To build research capability by facilitating nurses/AHPs to consolidate their skills and knowledge following completion of a MRes | Individual support and mentorship to facilitate timely dissemination of findings from MRes; implement findings into practice and enhance local research capacity through teaching and mentoring | Funds to release interns from clinical duties 1 day/week for 6 months and for a conference presentation or research training | 7 (4 nurses 3 AHPs) |

| Resources | To build research capability, to enable nurses/AHPs to collect, analyse and disseminate research using appropriate resources | Providing access to computer software such as NVIVO, SPSS, Survey Monkey; equipment such as Laptops, iPADs, digital voice recorders; research text-books and help with sourcing research papers |

Funds for software licences, equipment and books Administrative support |

Open access to resources |

2.7.2 What we achieved

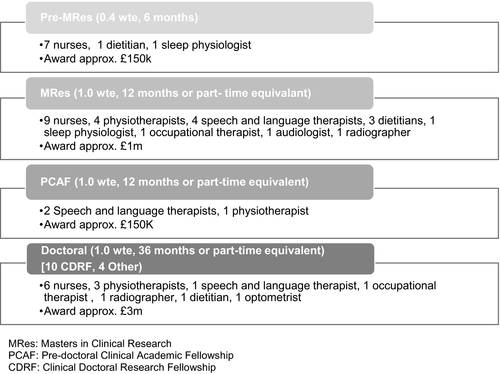

Building capacity was one of our major accomplishments. Prior to the programme, we were aware of only one nurse within the hospital who had applied for an NIHR fellowship, with no award being made. However, during the five-year programme of interventions we achieved considerable success across the NIHR CAC pathways, as well as other doctoral fellowship programmes (Figure 2). Although the data we collected from the surveys and focus groups does not illuminate the extent to which specific interventions contributed to outcomes documented in Table 1, we are confident in their combined impact. Certainly, internships which gave access to funded protected time were available annually and did facilitate the writing of competitive applications.

The number of nursing/AHP applications for a Health Education England (HEE)/NIHR funded MRes Fellowship increased year on year, with an almost 90% success rate and a total of 25 awards being made, albeit for some on their second or third attempt. We had notable success with two of the three Health Education Institutions (HEI) in the region funded to deliver these programmes, neither of which had any direct pre-existing clinical or academic links to our organisation. This research partnership continues to thrive, resulting in the successful appointment to an honorary professorship of one of the centre's senior researchers, as well as joint doctoral fellowship applications and supervision.

In the past five years of our programme, we generated £5 million research funding through competitive grants. We awarded 18 staff (ten Nurses, eight AHPs) a doctoral internship costing approximately £110,000 for salary backfill, with the aim of providing staff with dedicated time and tailored support to develop and submit a competitive application for the NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship Award. Of these, 14 completed the programme and submitted applications, with a further two nurses/AHPs receiving informal support and submitting applications, despite not undertaking an internship. This has resulted in ten NIHR and four non-NIHR funded Doctoral Level Fellowship Awards (six nurses, eight AHPs) with a total income in excess of £3 million. Of the remaining two staff whose submissions were unsuccessful, one was awarded a NIHR pre-doctoral fellowship the following year. Only one of the 18 staff members who participated in the doctoral internship programme has subsequently left the organisation.

A 6-month development internship was set up in response to feedback from nurses/AHPs about the challenges of consolidating their research skills and knowledge once they returned to clinical practice following completion of their MRes. Between 2016 and 2020, four nurses and three AHPs completed the internship, which has resulted in a range of outputs including oral and poster presentations at national and international conferences, journal publications and local initiatives aimed at building capability such as setting up of a journal club, mentorship and delivery of teaching sessions. A number of these interns went on to make successful applications for doctoral funding, showing continued transition along the pathway.

A need for support was also identified for those further along the CAC pathway who had completed doctoral studies. Introduced in 2016, a post-doctoral internship was offered with the aim of providing nurses/AHPs with time and support to develop a grant or fellowship application, to strengthen their research CV through establishing collaborations and/or publishing their work. The structure of the post-doctoral internship was tailored to the individual's needs in line with the known requirements of successful applications and included funded time and mentorship support from a senior researcher. Eligibility was expanded to all professions allied to medicine (as defined in the NIHR fellowship programmes) and reflected approaches made to the centre from these staff groups. Seven staff members (including one nurse, three AHPs and three psychologists) successfully applied to these internship calls.

In addition to our formal internship programme, we have provided more responsive support to nurses and AHPs to enable them to apply for the HEE funded Pre-MRes Internships and the Pre-Doctoral Clinical Academic Fellowship (PCAF) with considerable success. This support includes, for example, our ‘open door’ policy offering signposting and one-off consultations on research ideas, at whatever stage of development. Over time, we have seen capacity building amongst different professional groups, with growing success amongst physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, and dietitians, for example, as well as extending our reach to a wider group of AHPs including two radiographers and an orthoptist, sleep physiologist and an audiologist.

Influencing research capability across the hospital had more varied success. Nurses and AHPs were well represented at a multi-professional residential training weekend organised by the BRC, which led to funding and support for a further two residential weekends solely for nurses/AHPs; the first being for local staff and the second extended to those working in the NHS within the region. As a result of extending the training out-with the organisation, a wider CAC support group for nurses and AHPs was established. In terms of writing mentorship, 12 nurses/AHPs across the trust with experience of writing for publication received mentorship training provided by an external organisation; mentors were then allocated ‘mentees’. We initially targeted nurses/AHPs who had recently completed a Masters qualification and put a system of structured and informal support in place that included monthly meetings and agreed targets.There was a lot of enthusiasm for this initiative, assisted by improving accessibility to a wider range of staff, such as including the provision of evening and weekend research/writing sessions. Time to commit to writing, however, was a challenge for the mentees, and to date, only one has successfully submitted a manuscript to a peer-reviewed journal.

2.8 Evaluating change

2.8.1 What we did

To evaluate progress and the need for possible revisions to our programme, we repeated the staff survey in 2018. We used the methods described previously. We revised six of the questions to enable direct feedback on the interventions implemented. A specific question was also asked about support for staff on a CAC pathway. Completed surveys were returned by 370 staff (9%), including 138 nurses (37%), 68 AHPs (18%), 47 doctors (13%) and 111 others (31%).

2.8.2 What we found

Data entry was undertaken by two researchers (KO, JW), with the addition of two further researchers for the analysis, drawing comparisons over the two time points of data collection (FG, DS). In Table 2, we report changes since the original survey in the domains of culture, cognisance, capacity and capability; we use free-text quotes to illustrate the quantitative findings. Overall, although we found relatively few significant changes over time, the pattern of change differed between the domains of culture, cognisance, capacity and capability, described here in more detail.

| Domain | Topic | Changes from baseline | Free text quotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Keen to use research in practice | Significant increase from 89% to 93% of respondents; χ2 = 13.047; p = .005 | ‘There are many extremely knowledgeable clinical staff who could contribute significantly to research’ |

| Wanting more opportunities to share practice across the Trust | No change (82% vs 84%) |

‘Ensure research activity is highly valued, encouraged and supported within departments. This requires clear direction from the trust that research activity is ‘allowed’ as part of a clinical role’ ‘I think there will need to be a large shift in the culture at …(names the hospital) from the senior management teams to ensure research is given the priority that should exist for our patients’ |

|

| Cognisance | Understanding research terminology | No change—levels remain high (79% vs 81%) | ‘There are sufficient qualified high-level researchers who will help others, but this does not reflect a hospital initiative/infrastructure’ |

| Confident about using research in practice | No change (70% vs 75%) | ||

| Knowing how practice is influenced by research | Significant increase from 87% to 91% of respondents; χ2 = 8.072; p = .045 | ‘The organisation has a unique cohort of patients, and I believe we have a duty as a hospital to ensure that patient care is advanced by encouraging research. This is not the case sadly’. | |

| Know who to contact to start a research project | Slight insignificant decrease (53% vs 49%) | ||

| Awareness of available sources of support | No change |

‘The support we have on the clinical academic pathway has been really fantastic. We are very lucky here at …(names hospital) to have access to such amazing opportunities and be supported along route’. Nurse ‘More insight awareness training of R&D dept roles and responsibilities-including who's who- Training step by step of project registration –completion dissemination’ |

|

| Knowledge about the meaning of PPI in research | No change (58% vs 64%) | ||

| Able to provide relevant information to families about research | Significant increase from 29% to 37%; χ2 = 9.201; p = .027 | ||

| Able to direct families to the correct person about research | Significant increase from 56% to 69%; χ2 = 13.52; p = .004 | ||

| Regularly updated about research studies | Significant increase from 49% to 58%; χ2 = 11.158; p = .011 | ||

| Differences between professional groups (Kruskal–Wallis H = 20.81; p < .001); doctors (79%) and nurses (66%) reported higher rates compared with AHPs (41%) | |||

| Capacity and capability | Perceived barriers such as lack of time and skills and abilities |

No change No differences between professional groups in proportions reporting having insufficient time (unlike baseline findings) |

‘There is limited time and scope for research in clinical roles. It is not well supported and does not link towards promotion (especially in radiology)’ ‘I think the support for NHS consultants to develop research is very limited … Any research undertaken has to be carried out in addition to one's job plan and clinical work understandably has to be prioritised’ ‘Time. There is so much focus on increasing patient flow and capacity without putting extra staff in place that research is often seen as an "optional extra"; something you do "if you have time". |

| Would value opportunity to receive further training | No change—remained high (90%) | ||

| Access to training and development |

No change AHPs more likely to report not having access to training and development compared with either nurses (Z = −2.793; p = .005) or doctors (Z = −3.216; p = .001) |

‘…(names Research centre) provide regular training opportunities and support to develop a research culture within the AHP/nursing groups’. ‘Provide full on line journal access to all; make research training integral to ALL posts, ensure all have GCP training, encourage time for projects, posters, provide time and money to go to meetings, put keen fellows in touch with the BRC Junior faculty forum…’ |

|

| Access to resources (library facilities, online journals, etc) | No change | ‘On line access to journals is terrible. If you can't read other research you can't do research yourself’ | |

| Perceptions about support from staff | No change |

‘More support & Engagement for line managers from senior management team’ ‘Line managers are not supportive. They are reluctant to give us time out to undertake research even if the research is funded’ |

|

| Associations between regular staff meetings to explore ideas and staff feeling, able to understand research terminology, feeling confident about research in practice, feeling knowledgeable of how practice is influenced by research, having opportunities to reflect on practice and having access to training and development opportunities | Similar findings to baseline (r = .291 to .546; p < .01) | ||

| Being a lead investigator or co-applicant on a research grant | Higher proportion of doctors (34%, 47%) compared with nurses (both 4%), similar to baseline | ‘it always feels very medically dominated in terms of research at (names hospital). Nurses and AHP’s appear to have to work much harder to get the same opportunities for example honorary contracts at the (names partnership HEI) are common. Academic appointments for nurses and AHP’s are rare’….given that nursing is the largest staff group this appears unbalanced’ | |

| Presenting at conferences | No change |

Culture

As illustrated in Table 2, although the enthusiasm for undertaking research in practice had significantly increased amongst respondents (93% strongly agreed or agreed that they were very keen to use research in practice, compared with 89% at baseline), in their free text comments they continued to report structural barriers to achieve this ambition for the organisation. These barriers were reported by all professional groups, in particular the tension of prioritising clinical responsibilities for medical and AHP professional groups. Inequities in opportunity were further articulated for nurses, AHPs, healthcare scientists and non-clinical staff. Strong statements were made in relation to limitations for career development associated with pursuing research across many different professional groups.

Cognisance

There were improvements in awareness and understanding of how to support children and families participating in research (able to provide relevant information to families: χ2 = 9.201; p = .027; able to direct families to correct person: χ2 = 13.52; p = .004), but these improvements were not carried through to increasing knowledge of how to undertake research projects. However, knowledge about how research influenced practice had increased significantly (χ2 = 8.072; p = .045). There was also a significant increase in the proportion of respondents reporting that they were regularly updated about research studies, from 49% to 58% (χ2 = 11.158; p = .011), with the greatest increase being seen in nurses (49% at baseline compared with 66% at follow-up).

Capacity and capability

There were few changes in aspects related to capacity and capability, including perceived barriers such as lack of time and skills and abilities. In both surveys, respondents highlighted not only the challenges for all clinicians undertaking research but in particular continuing to develop research alongside clinical practice including at the post-doctoral level. In their free text comments, this related to the organisation's culture as much as to the capacity of professional groups and individuals.

… (HEI institution partner organisation) have a lot of support for full time academics as well as academic clinicians carrying out their own research. However non–academics feel left out of this support. There should be similar support for full time clinicians who carry out very relevant research in their fields.…

At the time of our first survey (2015), there was no recognised cohort of nurses and AHPs explicitly pursuing a CAC pathway; by the 2018 survey, 56 (15%) respondents were pursuing a CAC pathway, 35 of whom were nurses and AHPs.

2.8.3 What we did

We selected participants so that we could begin to explain some of our findings, by exploring in further detail the experiences of individual nurses/AHPs who had embarked on a CAC pathway. We invited all of those who had accessed one or more substantial elements of the interventions on offer (see Table 1), to take part in a focus group interview (n = 44): we undertook five focus groups. Invitations were sent via email along with a study information leaflet. Four nurses and six AHPs agreed to take part and included: (a) four undertaking or having completed an NIHR/HEE funded MRes or PCAF; (b) four undertaking a doctoral fellowship; and c) two with experience of preparing applications for doctoral fellowship funding. All had experience of undertaking a funded research internship in the organisation, which will have shaped their experiences, they did not all achieve success in funding applications to undertake further research.

Focus groups were conducted within the hospital setting during staff work time, with written informed consent being provided beforehand. With permission, each focus group was audio-recorded and facilitated by at least one experienced qualitative researcher who was not directly involved in supporting/supervising the participants (PK/KK/CRM). Discussion focussed on the drivers for participants undertaking research, their experiences of the process, opportunities and realities of combining research and academia with clinical work, including the infrastructures available to support them. Discussions were further framed in relation to their own definitions of CAC for healthcare professionals. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and data were stored in accordance with data protection legislation (Information Commissioner’s Office, 2020). The focus group data were analysed by two experienced qualitative researchers (KK & PK) using the framework approach (Gale et al., 2013; Smith & Firth, 2011). All transcripts were read independently by each researcher and coded inductively. The initial codes were reviewed jointly and further developed into a coding framework used to re-interrogate the whole data set.

2.8.4 What we found

We further expanded our understandings of culture, cognisance, capacity and capability drawing on the focus group data. Anonymised verbatim quotes are used for illustrative purposes. We have omitted the professional group to preserve confidentiality within a small cohort of respondents.

Culture

By having nurses and AHPs with particular areas of research interest and expertise dotted around different areas of the trust might be a step to becoming a research hospital … it’s a different type of research, which is equally important and it can address priorities of patients.

However, whilst the hospital aimed to be a research hospital, it was apparent that research was still not embedded into daily practice but rather seen as an additional aspect of some roles. Furthermore, where nurses/AHPs contributed to medical research they were often excluded from being named authors on publications.

Cognisance

Participants felt the success of previous CAC students had raised awareness of the nursing/AHP research centre within the hospital and the support and direction it made available. The visibility of students supported others with ‘personal drive to publish their own research/audit projects’ and to encourage future applicants to work with the centre to hone their research idea: ‘You can go off and do a sabbatical for one day a week for a build up to a project’.

Capacity and capability

Because you're a clinical academic, you can do that for a day and your supervisor is like, yes, go off and spend the day with the NIHR, and see where that leads.

I suppose the real fun of research is being able to answer a question you’re interested in. That’s where if you’re actually practising in the field, the questions are coming up in front of you all the time.

Where am I going to go? What am I going to do’ Yes, it is exciting to create your own role, but I’m really sceptical that we'll be able to do that.

It was felt that when returning to clinical roles, the time to maintain research skills became problematic because the clinical academic role is not recognised within the clinical area ‘I want to do something that combines both research and clinical and as far as I can see within this organisation that doesn't exist’. It was suggested that whilst this might represent the existing consultant nurse role, at least in theory, these varied widely in practice, with different levels of research activity. Furthermore, very few of these posts existed within this hospital in nursing, and none in the allied health professions. In response to these findings, our clinical academic programme lead successfully applied for the NIHR 70@70 Research Nurse Leadership Programme to take forward specific initiatives aimed at improving research cognisance, capacity and capability amongst nurses (https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/7070-nihr-senior-nurse-and-midwife-research-leader-programme/22750). Furthermore, we recognised a need to harness the relative success of our AHP cohort through the development of an organisational strategic plan for AHP research that includes dedicated research facilitator roles, an AHP Leads steering group including importantly the clinical managers and the research centre staff working in partnership, and a research conference, suggesting a cultural shift in the organisation for this professional group that has yet to be achieved for nursing.

3 DISCUSSION

We have presented our strategic approach to investigate the perceptions, experiences and contributions of the workforce to the research culture. We have described our initiatives to find creative solutions in building a sustainable model to support the development of nurse and AHP CACs. Our case study, focused on a small organisation delivering specialist tertiary level health care to children and young people and their families, illustrates high levels of interest and recognition of the value of research to improve care and treatment. Cognisance of research within individuals’ own clinical areas was highest. The confidence to support children and their families, including providing information and directing them to an appropriate person for further advice, improved over the time of the two surveys.

At an individual level, there was considerable success in building capacity reflected by the increased numbers of nurses and AHPs stepping onto a recognised clinical academic pathway. This cohort of over 30 clinicians have developed unique high-quality patient-centred research studies, across a shared focus of children with complex and rare health care needs; at the same time, bringing nearly £5 million of research funding income into our organisation. In our view, their success was in part facilitated through the financial support from the NIHR BRC grant that enabled funded internships. This was alongside intensive and highly skilled mentorship provided by the clinical academic programme lead, other senior researchers in the centre, as well as support from a growing cohort of peers, enhanced by their own knowledge, skills and personal drive. Embedding this programme of work within an established nurse/AHP-led research centre within the hospital was also key. Building research capability at the individual level was evident through the way that some of the nurses/AHPs moved successfully along the CAC pathway supporting others to achieve the same success. For example, two AHPs with doctoral fellowships are mentoring three PCAF fellows; two AHP post doc's have joined the supervision team of one doctoral fellow and one PCAF fellow; one nurse with a doctoral fellowship is mentoring a PCAF fellow. Informal mentoring, with a vibrant and supportive WhatsApp group, facilitates sharing of expertise, as well as social connections.

The culture of the organisation, and its infrastructure, have played a part in these individual achievements. This was in addition to other enablers, such as the BRC funding, links to a research intensive HEI, and more importantly, the support of individual heads of clinical departments. Evidence of success in the first two years of the programme was used to secure additional BRC funds for two further part-time posts, as well as funding the clinical academic programme lead up to 2022.

At an organisational level, between the two surveys, there was little change in relation to perceptions of capacity, capability and culture. Although there was recognition of the positive steps taken in building a critical mass of research-active staff, there was a perceived lack of translation of individual success to the organisation as a whole. Ongoing concerns were raised by some respondents regarding the lack of development of integrated research and clinical roles: this was reflected across all professional groups in our survey. Individual research talent was regarded as undervalued across the organisation—with respondents describing a culture of limited support, numerous challenges and a shared perception that although research activity was expected, clinicians’ research activities were not supported through a career infrastructure that rewarded research active and competent clinicians. In our view, despite being enthusiastic, skilled and knowledgeable professionals, research confidence was overall far below clinical confidence. We discuss how our experiences may be explained, drawing upon context beyond our own case, with a particular focus on nurses and AHPs.

Whilst all professional groups highlighted barriers to research, particularly in relation to having insufficient time, similar to other studies our survey revealed the experience of AHPs to be different to nurses (Trusson et al., 2019). Overall, AHPs reported more opportunities to be involved in research, and despite lacking access to training and development, they were more likely to have led research and disseminated findings than nurses. This might be because, as documented already in the literature, AHPs have a much longer history than nursing as an all degree profession (Pickstone et al., 2008). Added to which, in the hospital there are more doctoral prepared AHPs active in clinical research or working in research facilitator type roles who can act as role models, than nurses. In addition, four of the nine hospital AHP services secured funding for research facilitator roles who not only acted as role models but also were embedded to different degrees in the clinical departments. Perhaps, in contrast, engagement in research for nurses working in a clinical role was not perceived as a priority. As others have found (Fletcher et al., 2020), whilst the narrative across the organisation was that research is important, perceptions were that limited practical or substantively supported conditions were in place for this to take place, particularly for nurses.

Organisational constraints, evident in our work, are not unique, and like others, the need for an integrated ‘whole system’ approach to research capacity building has been highlighted (Golenko et al., 2012; Luckson et al., 2018; Matus et al., 2019). To be successful, research infrastructure needs to be combined with a positive research culture where research is valued and supported, enabling the generation of new knowledge and opportunities to translate evidence into practice (Matus et al., 2018), thereby influencing research engagement (Matus et al., 2019). Across all professional groups in our study, conflicting messages were reflected upon; research was felt to be celebrated and highly valued, but also somehow out of reach or even out of bounds for many. There were perceived tensions between clinical work and research aspiration, rather than all care and treatment reflecting a seamless integration of research and clinical work. Constraints, whether perceived or real, impacted on research engagement, and similar to others, lack of time, resources and opportunities were cited as ongoing challenges, in addition to mentorship (Marjanovic et al., 2019). Funding and lack of support leadership have been described as essential elements of any research capacity and capability strategy (Hartviksen et al., 2019). In our energies to focus on championing clinical academic roles, we designed interventions that would be most helpful in ensuring nurses and AHPs contribute to a research-active institution, by providing opportunities targeted at some of these known challenges. We anticipated that this might have some influence across the organisation. However, whilst we were able to harness the passion, energy and personal drive of a small number of nurses and AHPs to undertake research, characteristics known to fuel the best research (Maben & King, 2019), in the absence of research being operationalised as an organisational core value, our influence and impact to date have remained limited. This finding is important, and highly relevant, and links to what Cooke (Cooke, 2005) refers to as the sustainability of skills. Organisational infrastructure and supporting individual career planning and skills development are enabled by organisational processes (Gee & Cooke, 2018). Without these in place, career progression will not be facilitated. This remains our biggest challenge, in particular the recognition that research has yet to be truly embedded in a clinical role, in particular for nurses, and some AHPs. Our priority is to establish a structure for CACs; with a cohort of 14 doctoral prepared nurses/AHPs reintegrating back into clinical roles over the next five years, this will be essential. Our findings highlight the need for organisational structures, to reduce known barriers during transition to post-fellowship roles; barriers such as the availability of positions/new roles in which research activity is maintained (Newall & Khair, 2020; Richardson et al., 2019): and we would argue encouraged to flourish.

3.1 Limitations

Although the use of surveys and focus groups allowed us to reach wide and also provide some depth, there are a number of limitations to our work. First, this was a hospital-wide survey, from which we have, in the main, isolated data that relate to healthcare professionals. In terms of the culture, we recognise that all hospital staff have a contribution to make to ‘being a research hospital’. Second, we acknowledge that the survey respondents were different across the two time points, we cannot comment on individual ‘change’. Third, we might have only reached those who had an interest in research, our work presents the views of only a small percentage of the overall workforce. Fourth, this was an unvalidated survey, which we then adapted further, comparisons to other hospitals are therefore limited. Finally, although quantitative and qualitative interpretation was made throughout our work, there is scope for further study, using collective case studies and individual interviews, to examine findings across cases to draw out the nuances that relate to single disciplines, such as nurses, and to more explicitly illustrate a link between the programme of interventions and outcome.

4 CONCLUSION

Our single hospital case study has illustrated how local and national need has shaped a programme of interventions. Together these have impacted on cognisance, capacity and capability within the professions of nursing and allied health, resulting in a growing cadre of clinical academics. These interventions, targeted at the individual level, are having some positive influence on the research culture. Wider impact and reach are however still required. Our research centre is often described in isolation to clinical research and service delivery, yet we firmly believe that we are part of a health research system supporting the development of leading researchers to work within the NHS. We have illustrated the importance of this context; solutions to build CACs must target not only individuals but also the organisation in which they work, if we are to be really ready to harness research talent in clinical practice.

5 RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

Our strategic approach to planning and delivery of interventions, underpinned by leadership, commitment and support, has resulted in significant success at the individual level. The achievements of individual nurses and allied health professionals indicate that with supportive infrastructure capacity, cognisance and capability are not insurmountable barriers for determined clinicians. It is early days in the development of clinical academics and the positioning of such roles within NHS organisations. We have shared some of the building blocks we have put in place to support growth, to foster ‘home-grown’ clinical academics, to impact on research capability and capacity within our organisation. In doing so, hopefully we have illustrated the importance of understanding context and research culture to aid sustainability and impact on clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank everyone who completed a survey or participated in focus groups. In particular, we would like to thank Andrew Pearson, lead of the Audit Department, Dr. Christopher Morriss-Roberts, for support with focus groups, Lashanda Dillon, our administrator at the time, and in addition, hospital volunteers, who together distributed and collected surveys. This research was supported in part by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre: funding contributes to the salaries of Dr. Paula Kelly, Dr. Kate Oulton and Dr. Jo Wray. All of the views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Kate Oulton: conceived the study, contributed to the design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the article and final approval. Dr Jo Wray: contributed to the design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the article and final approval. Dr Paula Kelly: data collection, data analysis and interpretation, revising the article and final approval. Dr Kate Khair: data collection, data analysis and interpretation, revising the article and final approval. Dr Debbie Sell: contributed to the design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the article and final approval. Prof. Faith Gibson: contributed to the design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the article and final approval.