Aesthetic considerations for treating the Middle Eastern patient: Thriving in Diversity international roundtable series

Abstract

Background

The Middle East has a significant influence on the global aesthetic market. Within the United States and globally, patients with Middle Eastern heritage have a wide range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds that affect their perceptions of beauty and motivations to seek cosmetic treatment.

Aims

The aim of this roundtable was to discuss similarities and differences in anatomy and treatment preferences of Middle Eastern patients and explore how these differences may influence aesthetic practices.

Patients/Methods

In support of clinicians who wish to serve a diverse patient population, a 6-part international roundtable series focused on diversity in aesthetics was conducted from August 24, 2021, to May 16, 2022.

Results

The results of the fourth roundtable in the series, the Middle Eastern Patient, are described here. A discussion of treatment preferences is included, and specific procedural information is provided for commonly treated areas in this population (forehead, infraorbital area, and jawline).

Conclusions

Middle Eastern patients have a variety of aesthetic preferences, which are influenced by a wide range of cultural backgrounds, making it difficult to develop general statements about this demographic. There is an unmet need for research into this diverse group of patients to help physicians understand and incorporate their unique needs and desires into clinical practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Middle East has a long-standing and important influence on perceptions of beauty, dating back thousands of years and extending to today's global aesthetics market. In ancient Persia, primitive plastic surgery may have been in practice as far back as 3000 BC.1 Neferneferuaten Nefertiti, queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, continues to influence perceptions of beauty, even today.2 In the modern day, countries in the Middle East have rapidly growing beauty markets.3-6 Within the region, Iran has among the highest rates of cosmetic procedures, and Dubai, often referred to as the plastic surgery hub of the Middle East, has the highest concentration of cosmetic surgeons in the world, with 47 cosmetic surgeons per 1 million people.7-9 In Lebanon, a country of 6 million people, there are 1.5 million cosmetic procedures performed annually, and the aesthetics market continues to thrive despite economic challenges.10, 11 Dubai and Abu Dhabi have launched official initiatives to increase medical tourism and take advantage of this growing interest in the region; the medical tourism market in the Middle East and Africa is projected to be a $1.35-billion industry by 2027.4, 12

People from the Middle East also make up an important population of patients seeking aesthetic treatment in the United States. An estimated 3.7 million Americans claim Arab heritage. While most Middle Eastern Americans are born in the United States, common ancestry within this population includes, but is not limited to, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Iraq.13-15 The Middle Eastern patient population is widely diverse, and this diversity is reflected in populations within the United States, where there are a wide variety of ethnic and cultural attributes that should be considered when counseling patients and making treatment decisions for aesthetic procedures.

There is little content within the medical literature available to guide aesthetic treatment of Middle Eastern patients in the United States. In fact, demographic information about Middle Eastern populations in the US itself is difficult to obtain, as the Census does not include “Middle Eastern” as a race or ethnicity option.16 Despite this paucity of information, it is clear that people of Middle Eastern descent have unique and varied cultural, anthropometric, and personal priorities and concerns that should be considered as part of their medical care.15 As with other areas of aesthetics, especially those for which research is minimal, expert guidance plays a centrally important role in bringing to light key ideas that support optimal care and avoidance of incorrect assumptions about treatment approaches. This report, developed with the expertise of both Middle Eastern clinicians and clinicians who treat patients of Middle Eastern heritage in the United States, describes unique features and motivations within Middle Eastern populations regarding beauty standards and aesthetic preferences, in an effort to increase physician awareness and support culturally competent care. Importantly, clinicians should never forget that each patient is an individual with unique experiences and beliefs which may influence their treatment preferences, and the information within this manuscript only supplements a culturally informed treatment approach.

2 METHODS

A continuing medical education (CME) event series of six international roundtable discussions focused on diversity in aesthetics was conducted from August 24, 2021, to May 16, 2022. Each roundtable was conducted in an area of the world relevant to the demographic being discussed. The series included the Multiethnic North American Patient (Chicaho, Illinois, USA), the Latin American Patient (Medellin, Columbia), the African Patient (Johannesburg, South Africa), the Middle Eastern Patient (Dubai, United Arab Emirates [UAE]), the European Patient (Marbella, Spain), and the Asian Patient (Seoul Korea). At each location, leading aesthetic clinicians convened for a 2-hour roundtable to discuss the impact of race and ethnicity on anatomy and the best aesthetic products, techniques, and practices to achieve natural-looking results with minimal side effects. The results of the fourth roundtable in the series, the Middle Eastern Patient, are described here.

3 RESULTS

- Middle Eastern Populations are Ethnically Diverse. The Middle East refers to a region of the world including 18 individual countries in southwest Asia and northern Africa. Among these countries, the most populous are Egypt, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.17 People from the Middle East have a high degree of genetic and ethnic diversity, even within individual countries.18-21 Ethnic groups include Arabs, Persians, Jews, Turks, Berbers, Kurds, Armenians, Nubians, and Azeris.22 Three distinct racial clusters reflect primary ancestry within this population: Bedouins, Persian-South Asians, and Africans.18, 23-25 Genetic studies reveal significant variation across ethnic groups shaped by a complex demographic history over many generations influenced by admixture as well as events such as emigration, crusades, and colonization.18, 26-28

- Beauty Standards and Desired Features. Beauty ideals are not universal and vary significantly between cultures.29 These variations, combined with personal aesthetic preferences, shape the development of personalized treatment approaches for patients of Middle Eastern descent. Importantly, conflicts with ethnic identity or facial disharmony may result if Western-derived neoclassical canons of beauty are used as the only guide when planning facial treatment for Middle Eastern patients. The negative impact of such a conflict is highlighted by the association of acculturative stress, which results from adapting to a new culture, with body image issues and reduced psychological well-being.30-32 The negative impact of misaligned beauty standards is under-researched, but the importance of recognizing ethnic and cultural differences has been appreciated in other areas of medicine and naturally extends to aesthetics practice.33

-

More Research is Needed. To date, little research defines treatment preferences and considerations for the Middle Eastern patient population. While a recent consensus statement by Kashmar and colleagues, which included dermatologists and plastic surgeons from eight Middle Eastern countries, serves as an excellent resource for understanding facial beauty standards and implications for treatment, there remains a need for more systematic research on facial anthropometry, aging patterns, and patient preferences.25 Though the appearances of historical beauty icons in the Middle East can serve as a barometer of broader beauty standards, this approach has clear limitations, especially in the absence of research to inform how features of the aforementioned icons relate to the aesthetic preferences of modern patients. In addition, historically, Middle Eastern beauty icons were Egyptian and Iranian, while contemporary standards have shifted to include Lebanese and Jordanian features.25 The faces of beauty icons are generally oval-shaped and symmetrical, with thick, arched eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, full lips, well-defined cheeks and jawlines, and prominent chins; however, little is known about the degree to which these standards reflect beauty standards in the Gulf region.25

-

There is little published on anatomical differences that should be considered when treating these patients, which contributes to a lack of clinical knowledge, including aesthetic preferences and facial anthropometry. In cases where communication and awareness are lacking, this lack of understanding can lead to aesthetic clinicians imposing Western beauty ideas.34

The small amount of literature describing the anthropometry of people of Middle Eastern descent is focused on specific geographic regions and includes studies describing Iranian, Lebanese, Saudi Arabian, Egyptian, and Emirati anthropometry.35-42 Understanding these variations is part of a well-rounded baseline knowledge, and personalized assessment for each patient is needed. Facial shape, convexity, and proportions are highly variable among Middle Easterners, and perceptions of these features can be shaped by the high degree of ethnic diversity exhibited by people with Middle Eastern heritage.

- Motivations and Considerations for Treatment May Be Unique. A variety of factors affect a Middle Eastern woman's perception of her appearance and decision to seek cosmetic treatment. According to physician consensus, women report heavy influence of the media and their peers.25 Women under 40 years of age also list social media as a significant influence, and women over 40 years are influenced by husbands, friends, and partners.25 In a survey of Saudi Arabian women, 42% had had at least 1 elective cosmetic procedure and 33% had considered having one.43 Motivations for seeking an aesthetic procedure included improving appearance and self-esteem, attracting or maintaining attraction from a husband, and improving interpersonal relationships.

- Religious Considerations May Be Present: Islam is an influential religion in the Middle East that traditionally suggests modest dress for men and women. The decision to wear a head covering is personal and variable among Islamic women; the interpretation of and adoption of modest dress can vary from covering all hair as well as arms and legs to dressing similarly to Western counterparts.15 There are many different types of hijab that a woman might wear, but regardless of the type of garment worn, wearing a covering does not seem to affect whether women seek cosmetic treatments.43 However, among women who choose to wear a covering, the type and style of that covering can influence facial shape preference and aesthetic priorities.25 For patients who wear a full hijab in particular, a rounder face with fuller cheeks may be preferred, as this shape is often perceived as more attractive when framed by a scarf. Among women who wear head coverings, the eye and periorbital area are preferred areas for treatment.

3.1 Patterns of aging and common aesthetic concerns

The current literature does not describe common aging patterns specific to the Middle Eastern demographic. According to the one consensus group, the eyes, lips, and cheeks are the top aesthetic priorities among Middle Eastern women, followed by skin quality/tone/color, nose, and eyebrows.25 In the experience of the authors, the most common signs of aging in Middle Eastern patients include darkening under-eye area, sagging in the midface, and jowling, which may be explained in part by somewhat thicker skin.25, 44 The authors note that the most challenging aesthetic issues in Middle Eastern patients include heavy faces, disproportionately large or flat and prominently wide noses, thin lips (Lebanese, Jordanian, and Syrian patients), and jowling. Middle Easterners have a similar nasal base width as Caucasian North Americans, but greater nose height with a high arching dorsum and long nasal contour.38, 45 Demand for surgical nasal alterations is high in the Middle East, and in the experience of the authors, surgical correction as opposed to nonsurgical approaches is most often necessary to achieve satisfactory results both for the patient and the clinician.

Regardless of age, most Middle Eastern women desire a natural appearance without exaggeration of facial features.25 In general, women over 40 years want to appear younger and lifted, while younger women present with concerns around skin quality and facial shape or proportions. One author noted that it is not uncommon for younger women to report a desire to resemble beauty icons, even if this conflicts with the patient's natural features. An overview of general preferences for commonly addressed features is shown in Table 1; however, it should be noted that this guidance is not a substitute for individualized assessment to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

| Feature | Preference |

|---|---|

| Skin |

|

| Face shape |

|

| Forehead/brow |

|

| Eyes |

|

| Midface |

|

| Lower face |

|

| Neck |

|

During the roundtable, the panelists discussed several minimally invasive treatment approaches for common issues among their patients with Middle Eastern heritage. The following section summarizes this discussion and provides specific guidance for safely and effectively applying these approaches. While these treatment recommendations are by no means exhaustive, they touch on common techniques used to treat this patient population.

3.1.1 Special considerations for the skin

Though even skin tone and texture and overall skin quality are universal indicators of health and beauty, aesthetic desires surrounding skin characteristics can vary with ethnic background.46 Skin color is often a primary concern. Compared with Caucasians, people from the Middle East generally have darker, thicker skin that may have pigment alterations. Within this demographic, patients often voice a preference for skin tones that are lighter than their own and also actively seek treatment for pigmentary pathologies.25 Though regional influences may impact perceptions of ideal skin tone, the authors have noticed that most people from the Middle East seem to prefer Fitzpatrick skin types II-III while Egyptian patients prefer darker skin (skin types II to IV). Skin lightening is quite common among Middle Eastern women despite the negative side effects.47-49 In one recent study, 43.3% of Saudi women and 60% of Jordanians reported use skin lightening products.47 Patients may not be aware of the risks that accompany some of these treatments, and dermatologists and aesthetic clinicians play an important role in educating patients and promoting treatments and practices that support skin health and vibrancy as well as inclusive views of beauty.49

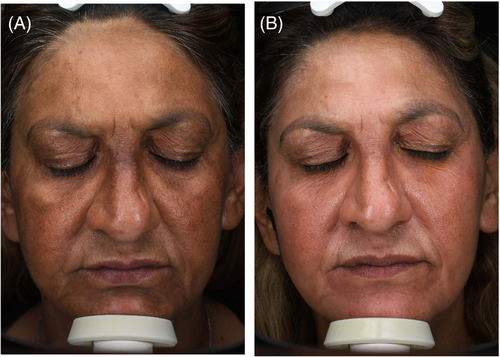

One survey within the United States identified uneven skin tone, discoloration (including melasma), dry skin, acne, and facial hair as top concerns for Arab American patients.50 Treatment for melasma, which is a common skin disorder among people with pigmented skin, is challenging because the pathophysiology of the condition is not just a pigmentary issue from aggregation of melanin and melanosomes, but also includes mast cells, structural issues like solar elastosis, altered basement membrane, and increased vascularization.51, 52 Thus, management requires a multimodal treatment response.51 A aggressive baseline treatment may involve oral tranexamic acid 250 mg twice daily for 3 months in addition to lightening or other treatment approaches (e.g., topical hydroquinone).53 For a more advanced approach, adding laser-based treatments can improve outcomes and is recommended to address the multiple components of melasma. Figure 1 shows an example of this type of approach. In the authors' experience, the best approach is to combine a picosecond laser and microneedling with radiofrequency. Emerging data suggest that microneedling with radiofrequency restores the basement membrane, which promotes clearance of melanin.54, 55 Above all, patients with melasma should make lifestyle changes to increase sun protection, including frequent application of anti UV-A + UV-B + VL sunscreen.

3.1.2 The upper face

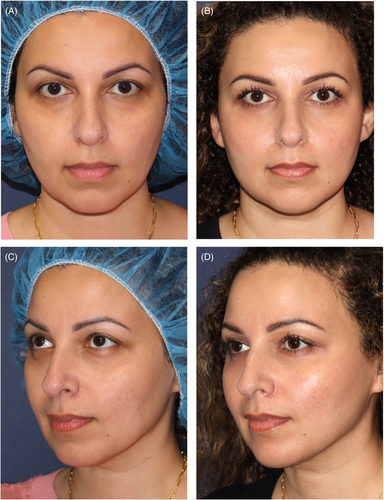

During discussion, the authors noted that while there is a wide range of facial shapes in Middle Eastern patients, the convexity of the forehead is a key feature for which patients often seek treatment. While several studies of areas across the Middle East report that a straight profile is preferred in some regions, forehead contour (often including the upper brow) is a feature many Middle Eastern patients wish to modify (in the experience of the authors).25 Irrespective of overall facial shape, it is important to ensure that any hollowing in the temple area is managed to ensure youthful facial shape and support the appearance of the eyes. For the patient shown in Figure 2, management of the temples, as well as management of the mid and lower face has supported a more youthful and balanced aesthetic.

3.1.3 Forehead contour

- When managing forehead contour, it is important to assess and treat the temples first, which not only is important for harmonious appearance in the upper face, but also may facilitate repositioning tissue within the midface.56 When injecting the temple, it is important to inject the portion of the temple within the hairline to take full advantage of indirect lifting infects.

- In the inferior forehead, vessels travel deep below the frontalis muscle with the major branches traveling between the frontalis muscle and the fascia. The fascia envelopes the roof and the retrofrontalis fat compartment. Supraorbital and supratrochlear branches traverse this region from the orbital septum upward. Superiorly, injecting into the interfacial plane can improve forehead contour and requires a comparatively small amount of product.

- For the brow, deep injection below the muscles can help feminize the brow by softening a prominent suprabrow ridge.

- In the forehead and temple, a 1:1 dilution of calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHA; Radiesse [Merz; Raleigh, NC]) or hyaluronic acid (HA) can be used to improve forehead shape. Irrespective of product, the authors recommended a large-bore 22-G cannula for injection.

- Dynamic lines in the forehead and glabellar complex should be managed proactively with Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A); however, etched-in lines can be managed with a soft filler injected with a 30- or 32-G needle placed intradermally.57

3.1.4 The midface and infraorbital area

- It is important to understand that apparent volume loss can actually be due to shifts in volume. For example, infraorbital volume loss accompanied by volume repositioning in the lower face may be improved by adding volume to the upper cheek, lateral to the line of ligaments, which can provide some repositioning in a cephalad direction. This creates the appearance of tissue lifting while addressing infraorbital hollowing. In addition, the indirect effects of this injection technique may reduce or eliminate the need for more medial tear trough injection. For example, the patient shown in Figure 3 was treated in both the cheek and tear trough, while in Figure 4 improvement in the tear trough can be appreciated even though the patient was not injected directly in the infraorbital area. Importantly, both patients were treated in a holistic fashion, and each received injections in other areas as well.

- When injecting filler in the upper cheek and infraorbital area, a single entry point and deposition of product with a cannula is recommended. The entry point should not be on the malar mound (an area prone to swelling), but instead 1 to 2 cm below the orbital rim lateral to the canthal line.58 From this entry point, injection can be directed straight into the lateral suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) compartment or, by entering this same point at 90-degree angle and turning the cannula, the medial deep fat compartments may be accessed. Of note, the SOOF has a high surface–volume coefficient (0.94), so it is possible to obtain a high degree of surface projection with a minimal amount of filler product injection in this area.59

- To volumize the infraorbital area, the authors may carefully and cautiously go through the orbital retaining ligament (ORL). Instead of a retrograde threading injection approach, depositing microdroplets while withdrawing the cannula can prevent the filler from coalescing and causing eyelid swelling.58

- A robust HA filler can be placed along the prezygomatic space to camouflage the lid-cheek junction.60 A halo effect from the hydrophilic properties of HA fillers will gently augment the lid-cheek junction to create a smooth transition. If the lid-cheek junction hollow is severe and/or there is prominent blepharoptosis, a small amount of HA can be placed superior to the ORL by carefully traversing the ORL with a blunt cannula and placing a 0.05-cc deposit of a low G′ filler with minimal propensity to swell. However, this is an advanced technique that is not recommended for novice injectors.

- Caution is advised when injecting around the orbit to avoid the infraorbital foramen, which gives rise to the infraorbital artery and the infraorbital nerve.61 The canal falls within a rectangular zone of variability measuring 14.30 mm by 10.60 mm. This zone lies 3.50 mm below the infraorbital rim, 7.10 mm medial to the piriform aperture, and 11.60 mm from the lateral orbital rim. The infraorbital artery exits in a medial direction, and a medial to lateral injection in a superior tangential pathway would be more likely to enter the canal. Placing filler too superficially may increase swelling, which can lead to an unnatural contour, and especially in Middle Eastern patients, can worsen shadowing in the area due to a greater distance created between a more recessed globe and maxillary prominence. For some patients, volume replacement and minor swelling can result in distention of veins and a blue discoloration under the eyes. In some patients, the authors recommend pre-treating the periocular veins with a long-pulsed 1064-nm laser (Vbeam Prima [Candela Medical, Marlborough, MA]) to avoid dilation and discoloration.

- When treating the infraorbital area, it is important to use a filler that does not cause significant swelling (i.e., less hygroscopic) and to use a small amount of precisely placed product in deeper planes. This is particularly important if the medial aspect is to be injected. To volumize this region in deeper compartments, one of the authors recommends an HA filler like Vycross gel 20 mg/cc (Juvéderm; Voluma [Allergan Aesthetics, Dublin Ireland]) or an XpresHAn filler (Restylane Contour [Galderma, Fort Worth, TX]).62 If the patient has little fat and/or there is a need to simultaneously inject the superficial compartments, a dynamic filler with low hydrophilicity such as Resilient Hyaluronic Acid-2 gel (RHA2; Teoxane Laboratories, Geneva, Switzerland), or Cohesive Polydensified Matrix-HA (CPM-HA; Belotero Balance [Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC]) can be used.58 Volumization with transplanted fat in the upper cheek, infraorbital hollows, and temples is also an option that one of our authors may use to provide a natural-looking outcome with complementary regenerative properties. However, there is a longer learning curve for this modalities and more complexity involved in offering this procedure. Thus, fat tends to not be a first-line option for most injectors.

Dyspigmentation in the infraorbital area can be treated with a pulse-dye laser or 1927 thulium laser. Laser treatment should be administered 2 weeks before or after filler and/or toxin treatment. Device settings depend on the patient's skin color and desired recovery time. For the thulium laser, inhaled nitrous gas (50% oxygen 50% nitrous oxide) can be used to optimize patient comfort. In darker-skinned patients, consider applying a class II or III topical steroid after treatment to minimize postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: the steroid should be applied twice daily for 3 days after treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear sunblock that is a minimum of 50 SPF (reapplying every 2 hours even if inside). After 1 week, an 8% minimum hydroquinone topical pad may be used. Tripeptide hexapeptide serum (ALASTIN Skincare [Carlsbad, CA]) can also improve healing following the procedure.63

Though the use of neuromodulators to support a rejuvenated appearance for the eyes is standard, patients with deeper-set eyes may benefit from filler combined with toxin treatment.64, 65 Intra- or just-subdermal injection of microdroplets of 1-2 U/mL onabotulinum toxin can be placed infraorbitally (at the midpupillary line along the orbital rim) to relax the orbicularis muscle, which address some darkening by improving light reflection around the eye.

3.1.5 Lower third—chin and jawline

- For Middle Eastern Men, a strong, well-defined jaw and gonial angle are desirable. For female patients, a highly defined jawline is sought after. The ideal angle is variable and dependent on individual patient proportions; however, a mandibular sweep angled superior should be 120 to 130° for female patients and ~ 130° for males (less than 120° makes the jawline more square), with the gonial angle aligned with the mental crease.66, 67

- Uniquely, slimming of the face with BoNT-A to the masseter muscles is rarely used as a treatment for either male or female Middle Eastern patients. There is generally very little desire to slim the lower face.

- High G' fillers (e.g., CaHA or Vycross 25 mg/cc) or a larger particle NASHA 20 mg/cc HA filler (Restylane Lyft [Galderma, Fort Worth, TX]) can be used to define the jawline. Use of a more structural filler is indicated in those with thicker skin who require a robust product to project and accentuate the jawline or chin. Management of the chin and jawline to create a more defined appearance is shown in Figure 4.

- To treat the chin, the injector can enter through the midpoint of the mentum and inject either side. For patients with wider chins, the injector may choose to enter laterally and deposit filler in a line along the jawline. A smooth transition between the lip and chin along the labiomandibular sulcus is necessary to prevent the appearance of a pointy chin. For female patients, the chin should be no wider than the distance between both medial canthi, and attention must be paid to both saggital projection and the length of the chin.

- When performing injections in the chin area, avoid the ascending submental artery, which is a branch of the submandibular artery that enters the chin deeply, approximately 6 mm off the midline and then traverses more superficially as it ascends toward the lower lip. A vascular injection can compromise the vessels leading back to the floor of the mouth via the lingual artery and cause ischemic complications in the tongue.61, 68 Injecting carefully with a large-bore cannula (22-gauge) or deep in contact with the bone when using a needle can be effective and reduce the risk for an intravascular injection. When defining the entire mandible from gonial angle to gonial angle, multiple syringes of product may be needed. Importantly, while using sufficient product is an important procedural consideration in this area, too much product in the chin (>4 cc) may lead to soreness, and rarely to discomfort with chewing or sensitivity/soreness.69 While uncommon, excess superficial injection of filler can lead to hypervascularization and skin discoloration.

4 CONCLUSIONS

People from the Middle East represent a growing and influential demographic within aesthetics. Physicians who treat these patients should take into account the extremely wide range of ethnic and cultural features among Middle Eastern patients to ensure appropriate treatment selection, optimal outcomes, and patient satisfaction with treatment. More research is needed to better understand the needs and desires of this important patient population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.F. and S.D. designed and orchestrated the Thriving in Diversity roundtable series. S.F, H.G, N.F.G., S.NM, O.A., and S.D. participated in the roundtable and reviewed and approved the manuscript. G.V. (listed in the acknowledgments) wrote the manuscript under the direction of the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Ginny Vachon, PhD, Principal Medvantage, LLC, Atlanta, Georgia under the direction of the authors. Funding for this support was provided by a CME grant funded by Abbvie, Merz, and Solta.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding for this CME event was provided by Abbvie, Merz, and Solta.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

All patients treated as part of the is CME activity provided consent for treatment and all patients shown within this manuscript provided permission for their photographs to be used.

DISCLOSURES

S. G. Fabi is a consultant/speaker for Abbvie, Galderma, Merz Aesthetics, Revance, Endo Aesthetics, NC8, CROMA, and Ortho Dermatologics; has received research support from Abbvie, Galderma, Merz, Revance, Endo Aesthetics, CROMA, Ortho Dermatologics, and Raziel; and holds stock in Abbvie, INC and Revance Therapeutics.Hassan Galadari, Nabil Fakih-Gomez: No disclosures. Dr. Nazarian is a consultant and speaker for Galderma and InMode. Dr. Artzi is a consultant/speaker for Galderma, Lumenis, Alma lasers, Novoxel, Entitymed, IBSA, and Venus Concept. Dr. Dayan is a consultant/speaker for Abbvie, Galderma, Merz, Revance, Endo Aesthetics, CROMA, and InMode; has received research support from Abbvie, Galderma, Merz, Revance, and Endo Aesthetics; and holds stock in Abbvie, INC, and Revance Therapeutics.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.