Household Financial Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Instrumental Variable Approach

All results, interpretations, and conclusions expressed are those of the research team alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Rhode Island, the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, FINRA, or any of its affiliated companies.

ABSTRACT

Using data from the 2021 wave of the FINRA Foundation's National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), collected between June and October 2021, we found that adults in households where at least one member contracted the COVID-19 virus had lower financial wellbeing and were more likely to be financially fragile than those in which no members had contracted the virus. Our analyses also revealed that COVID-19-positive households were more likely to report experiencing objective general financial difficulties and difficulties specifically tied to medical costs and debt. Further, to assess whether evidence of a causal link between a COVID-19 infection and negative financial outcomes existed, we used state vaccination rates as an instrumental variable. Our analysis supported a causal link and contributes to a growing body of research on the effects of the pandemic on household finances. Together, our findings can inform how policy makers and other stakeholders may want to respond to the financial repercussions caused by future global health crises and disruptions.

1 Introduction

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for households in the United States are wide-ranging and difficult to fully gauge, with new financial and health consequences still being uncovered. At the time of this writing, 103 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States, with a death toll of over 1.2 million (WHO 2023). The global pandemic, one of the most severe health crises experienced in the last 100 years, has not only impacted public health, but has had a vast range of effects on the economy, including high unemployment rates, the closure of businesses and schools, and a large drop in the national GDP and the stock market in 2020 (see Bauer et al. 2020; Milesi Ferreti 2021 for an overview of the US during the pandemic).

The COVID-19 outbreak, particularly early on, resulted in global disruptions and unparalleled challenges to individuals, families, communities, businesses, and economies. The virus resulted in widespread sickness and millions of deaths worldwide. As in many other countries, measures were taken to curtail the spread of the virus, including implementing social distancing requirements, lockdowns and quarantines, closing schools and limiting social gatherings. Economies were rattled, markets tumbled, businesses shutdown, and millions lost their jobs. Indeed, changes in employment during COVID-19 dwarfed those occurring in other recessions, particularly early on (Montenovo et al. 2022), with a high degree of heterogeneity based on occupation and the feasibility of working from home (Brodeur et al. 2021; Gezici and Ozay 2020). Social distancing measures, common during the pandemic, had negative consequences on physical health, mental health, and family stress, with women bearing the brunt of the adverse effects (Brodeur et al. 2021; Sánchez et al. 2020). The global lockdown also had impacts on a wide range of outcomes from food security and the economy to education and mental health (Onyeaka et al. 2021). This review of published studies by Onyeaka et al. (2021) found that, with the exception of a potential reduction in air pollution, COVID-19 has been harmful for household's finances, health, and mental wellbeing.

While robust evidence has identified effects of COVID-19 on household financial wellbeing (Khetan et al. 2022; Richards et al. 2022; Roll et al. 2022), this study adds to existing literature by examining the causal role of COVID-19 infection on people's ability to manage their finances and make ends meet, comparing the financial outcomes of adults in US households that experienced COVID-19 directly (at least one household member with a positive COVID-19 test result or diagnosis) to those who did not.1 Using data from the FINRA Foundation's 2021 State-by-State National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), we examine these differences at the household level. Importantly, to determine the possible causal effect of COVID-19 infection, we use state-level vaccination rates as an instrumental variable, allowing us to infer causal claims about the relationship between testing positive for COVID-19 and financial outcomes.

Data were collected between June and October 2021, a period during which the Delta variant took hold of the US. By the end of July 2021, several measures had been taken to protect people from the virus and slow its spread. In our sample, “COVID-19-positive households” identify those in households in which a member was infected with COVID-19 relatively early in the pandemic, a time when the US was still wrestling with some pandemic-related challenges. As such, this study sheds light on how adults in US households grappled with a complex economic environment and a changing world, amid considerable temporary cash transfers. The findings can be used to inform policy regarding how to prepare for future pandemics or global disruptions and help identify the demographic groups that may be most vulnerable during challenging economic times.

2 Literature Review

2.1 COVID-19 and Objective Indicators of Financial Difficulties

With job losses and dwindled incomes, many households likely experienced constrained finances, which may have led to financial difficulties. Decreased cash inflows often result in a strained ability to make ends meet, shifting spending patterns and increasing a need for borrowing (Round et al. 2020). This may particularly be the case for those already in precarious financial positions. Prior to the pandemic, many American households were already dealing with various aspects of financial vulnerability. Valdes and Mottola (2021) found using data from the NFCS that four in 10 households lacked the financial resilience in 2018 to deal with a financial crisis such as a pandemic. African Americans and those in low-income households were more likely to be financially fragile (Lusardi et al. 2021). A decade before, research also showed that approximately one quarter of Americans could be described as financially fragile by their inability to come up with $2000 in 30 days to cope with an emergency (Lusardi et al. 2011).

More recently, financially vulnerable households suffered the greatest financial strain (Bruce et al. 2022) and decreases in income (Immel et al. 2022) during the pandemic. Less creditworthy consumers found it harder to access credit, while paying higher interest rates on newly issued credit cards (Horvath et al. 2021). Nearly half of adults making low- to middle-incomes experienced an unemployment spell in 2020. In fact, the Pew Institute (2022) reported that unemployment benefits were the main source of income for many households during the pandemic. The scope of financial vulnerability early in the pandemic was large, with nearly one in five adults classified as fragile during this time period (Clark et al. 2021).

While households, particularly those financially vulnerable, reported general difficulties during the pandemic, the extent to which COVID-19 impacted their medical-related debt is less clear. Guttman-Kenney et al. (2022) found no evidence of increases in medical debt severity during the pandemic. The researchers attributed the lack of association between COVID-19 and medical debt to declines in elective medical procedures as well as healthcare related-policies that served as safety nets, together offsetting the costs of medical debt during the pandemic.

However, a majority of research examining the financial sequalae of COVID-19 looks at households overall rather than taking into consideration whether a household experienced a direct impact of a COVID-19 diagnosis. It is likely that households that were directly impacted by a positive COVID-19 diagnosis (i.e., with that person or a member of their household diagnosed with COVID-19) experienced more acute financial consequences, both generally and related to medical expenses.

2.2 COVID-19 and Perceptions of Financial Wellbeing

While the economic costs of the pandemic are somewhat clearer, the perceived impact of the pandemic on households' financial wellbeing does not necessarily mirror the broader economic context. The Consumer Financial Protection Board (CFPB) defines financial wellbeing as “having financial security and financial freedom of choice, in the present and in the future” (CFPB 2015, Page 7). Financial wellbeing, which can be gauged via constructs like financial anxiety and perceived future financial security, do not necessarily reflect individuals' financial expectations for the country or world. Financial anxiety has been described as feeling anxious or being worried about your personal finances (Archuleta et al. 2013). Barrafrem et al. (2020) found that individuals tend to be less pessimistic about their own financial future relative to broader financial outlooks, with characteristics like financial knowledge and psychological traits playing a role. Other studies have found that individuals facing financial vulnerabilities, including lower available resources and increased household expenses were at higher risk of reporting negative impacts from the pandemic, with those most vulnerable more likely to be Hispanic, non-White, and having less than a college degree (Bruce et al. 2022). Shim et al. (2009) developed a model explaining the financial wellbeing of young adults using personal and family antecedents and financial factors such as financial knowledge and financial attitudes. Factors affecting wellbeing include those that pose a threat to financial security and anxiety, like job stability (Vieira et al. 2021). Taken together, these findings suggest that individuals' financial vulnerabilities, some of which preceded the pandemic (Lusardi et al. 2011, 2021), may have been exacerbated by pandemic conditions, leading to decreased financial wellbeing (Xu and Yao 2022).

Risk of COVID-19 infection varied by characteristics like health, socioeconomic, and living circumstances (Shifa et al. 2022). Notably, many of the risk factors associated with greater financial vulnerabilities were also tied to a higher likelihood of being infected by COVID-19. In addition, some research has found that COVID-19 infection itself is associated with psychosocial impacts among some populations (Mohammadian Khonsari et al. 2021), with those infected experiencing higher levels of mental health problems, impoverished quality of life, and greater financial hardship relative to those without infection.

While a host of studies have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population's financial and psychosocial state, to our knowledge, very few have investigated possible differences between those whose households were directly impacted early in the pandemic via a positive test or diagnosis versus those who did not face infection. The current study adds to the literature on the pandemic by leveraging a national-level dataset collected at a central point of the pandemic to compare differences between households with and without a positive COVID-19 diagnosis. Importantly, we further our understanding of the relationship between COVID-19 and financial behaviors and perceptions by employing an instrumental variable approach to better understand if testing positive for COVID-19 is causally related to a host of financial outcomes.

2.3 Conceptual Framework

Our choice of dependent variables (listed below) was guided by our research question, the framework on financial capability provided by the NFCS (Valdes et al. 2024) and previous research on financial capability and wellbeing (Xiao and Porto 2017; Xiao et al. 2009). While no single, agreed-upon definition of financial capability exists, the NFCS borrows from earlier work (Atkinson 2007) and focuses on four components of financial capability: (1) Making Ends Meet, which examines respondents' ability to pay their bills and service their debt; (2) Planning Ahead, which examines whether respondents are saving for longer-term needs, like retirement or an unexpected emergency; (3) Managing Financial Products, which examines the financial products respondents use and how they use them, for example, credit cards; and (4) Financial Knowledge and Decision Making, which explores respondents' financial knowledge and self-perceptions of their knowledge, including numeracy skills. Given that our research question aims to assess the financial impacts of COVID-19, we focused on respondents' near-term ability to make ends meet, with variables reflecting financial strain from both objective and subjective perspectives.

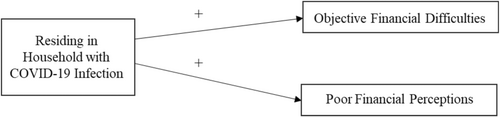

As noted in the Literature Review, the work that has been done looking at the relationship between COVID-19 and a variety of outcomes suggests that the pandemic had a deleterious effect on a wide range of variables. Consistent with these findings, we suggest that the disruptive nature of a COVID-19 infection within a household affected their ability to make ends meet, reflected in objective financial difficulties, both generally and specific to medical debt and medical expenses, as well as poor financial perceptions. Figure 1 captures the nature and direction of these relationships.

3 Methodology

This study uses data from the 2021 wave of the FINRA Investor Education Foundation's State-by-State National Financial Capability Study (NFCS). The sample consists of adults (18+) across the US, with about 500 respondents per state, plus the District of Columbia, resulting in a total sample size of 27,118. The sample for the NFCS is obtained from established opt-in online non-probability research panels using quota sampling. Unless otherwise noted, the analyses are weighted using national weights that accompany the NFCS data, which makes the data representative of the adult US population in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, education, and Census Division. The 2021 State-by-State online survey was fielded between June and October of 2021 (Lin et al. 2022). For more details on survey design and methods, see Mottola and Kieffer (2017).

We compare COVID-19 infected households to non-infected households on a series of relevant financial outcomes. To assess the causal relationship between contracting (or living in a household where someone contracted) COVID-19 and subsequent financial outcomes, we used instrumental variable analysis.

3.1 Measures

3.1.1 Primary Explanatory Variable

Respondents were asked, “Have you or anyone living with you tested positive for or been diagnosed with COVID-19?” A total of 15.7% respondents reported a member of their household had tested positive or been diagnosed with COVID-19. The question was coded as a binary indicator, where 1 represents households that experienced COVID-19 and 0 represents households that did not experience COVID-19 at the time the data were collected. It is the main explanatory variable of interest in the present study. The data were collected before the Omicron variant was prevalent in the US but after three types of vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and J&J/Janssen) were widely available.

3.1.2 Dependent Variables

3.1.2.1 Objective Financial Difficulties

3.1.2.1.1 General Difficulties

To assess objective measures assessing general financial strain, we examined the following variables, which we termed general financial difficulties: (1) Difficulty Paying Expenses (Xiao et al. 2009), (2) Spending More than Income (Porto and Xiao 2021), (3) Overdrawing Checking Account (Robb et al. 2019), and (4) Late Credit Card Payment (Dew and Xiao 2011). All were independently coded as dummy variables, with 1 representing affirming the behavior in the previous 12 months and 0 indicating otherwise. Note that the four variables represent objective assessments of difficulties related to money management.

3.1.2.1.2 Medical Financial Difficulties

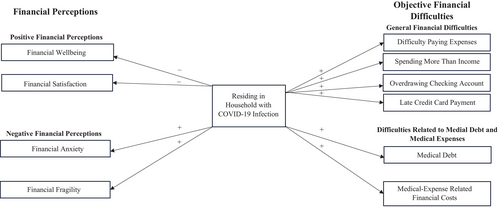

To examine the impact of experiencing COVID-19 on difficulties related to the intersection of health and financial outcomes, we used two measures previously examined in health-related reports (e.g., Karpman and Caswell 2017; Spiegel and Fronstin 2022): (1) Medical Debt and (2) Medical-Expense Related Financial Difficulties. Medical Debt was assessed with one-item asking if the respondent has any unpaid and past due bills from a health care or medical service provider. We categorized respondents as having medical debt (and coded medical debt as 1) if they answered ‘yes’ to this question and as not having past-due medical debt if they answered ‘no’ (and coded as 0). Medical-Expense Related Financial Difficulties were assessed by a series of items asking whether respondents had done any of the following for financial reasons during the last 12 months: (a) not filled a prescription, (b) skipped a medical treatment, test, or follow-up, or (c) not gone to a doctor or clinic. Respondents who answered ‘yes’ to at least one of these questions were categorized as experiencing financial difficulties related to medical expenses (and coded as 1) while those without these financial difficulties were coded as 0. Figure 2 expands the conceptual framework to include the nature and direction of relationships of the specific variables examined within the study.

3.2 Financial Perceptions

Respondents' perceptions about their financial situation were assessed using (1) the Financial Wellbeing Scale, a five-item scale created by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB 2015), (2) Financial Satisfaction was measured via a single item (“Overall, thinking of your assets, debts and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition?”) and rated on a 10-point Likert scale, from 1 “Not at all satisfied” to 10 “Extremely satisfied,” (3) Financial Anxiety was measured via a single item (“Thinking about my personal finances can make me feel anxious.”) rated on a 7-point scale from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 7 “Strongly agree,” and (4) Financial Fragility was measured via a widely used one-item measure (“How confident are you that you could come up with $2,000 if an unexpected need arose within the next month?”). All variables were coded as binary for comparison purposes except for financial wellbeing which follows the scoring method from the CFPB Abbreviated-Version Questionnaire guidelines (CFPB 2015).

3.2.1 Instrument Variable—State Vaccination Rates

As a solution to potential endogeneity, we re-estimated the impact of a positive COVID-19 diagnosis at the household level by using state vaccination rates as of August 1, 2021 (CDC 2023) as the main instrument to predict experiencing COVID-19 at the household level. Instrumental variable analysis is a procedure that can be used when explanatory variables are endogenous (or correlated with the error term), which can occur if omitted or confounding variables are not included in the regression. In this case, a variable or “instrument” that is correlated to the explanatory variable but has no direct effect on the outcome can be used to estimate the causal effect between the predictor and outcome (Crosby et al. 2010; Baiocchi et al. 2014). Because the association between COVID-19 infection and financial outcomes may be confounded by unmeasured factors like occupation, adherence to social distancing measures, and mask use, we used state vaccination rates as an instrument to control for endogeneity and thereby estimate the causal effect of COVID-19 infection on financial outcomes. While the timing of the infection and if the specific households were vaccinated is unknown, our instrument captures variation in the infection rates based solely on state vaccination levels.

State vaccination rate had a sizeable negative association with COVID-19 cases up to December 2021 (Barro 2022). State-level vaccination rates were associated with factors such as politics (Albrecht 2022), county-level vulnerability, and urbanicity (Barry 2021), and vaccine hesitancy was associated with race, income, and educational attainment (Khubchandani et al. 2021). While the decision to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was at the individual level, higher levels of state vaccination offer some protection to all individuals, even those that are unvaccinated. The vaccination threshold necessary to achieve herd immunity to COVID-19 is debatable (Morens et al. 2022) but higher levels of vaccination decrease infection rates due to herd effect (John and Samuel 2000). We also recognize that differences within each state on vaccination access and demand might exist; however, using state-level vaccination rates provides a proper equivalence to our use of clustering standard errors at the state level. Vaccination rate, as such, is a good exogenous instrument since no single respondent can affect it directly, and it should not affect financial outcomes directly but has explanatory power to our endogenous treatment variable of contracting COVID-19. Appendix A displays original survey questions and variable coding for the analysis.

3.2.2 Control Variables

In addition to the main variables of interest listed above, a set of controls was included that have been found in previous research to contribute to financial outcomes or perceptions (Ralphs 2024; Sinha et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2024). Controls included age, age squared, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, income, employment status, marital status, presence of dependents, banking status, homeownership, and indicators of disability and retirement status. Given the nature of this study, we also included variables that indicate whether the respondent received a stimulus payment from the federal government during the pandemic (Stimulus) and whether they were laid off or furloughed due to the pandemic (Job Loss due to COVID-19). Table 1 contains unweighted summary statistics for the variables used in this study. All regressions models used the weights noted above.

| Variables | Full sample (N = 26,762) | Non-COVID-19 household (n = 22,509) | COVID-19 household (n = 4253) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean) | 47.50 | 48.82 | 41.52 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White non-hispanic | 73.98% | 74.64% | 71.97% |

| Black non-hispanic | 10.02% | 9.81% | 10.30% |

| Hispanic | 8.39% | 7.62% | 12.04% |

| Asian/Pacific islander non-hispanic | 4.40% | 4.79% | 2.23% |

| Other | 3.21% | 3.14% | 3.46% |

| Male | 45.97% | 45.27% | 49.54% |

| Married | 48.97% | 48.87% | 50.88% |

| Has dependents | 34.40% | 32.12% | 45.94% |

| Income brackets | |||

| Less than $25 k | 26.16% | 26.07% | 25.79% |

| $25 k–$75 k | 43.41% | 43.76% | 41.50% |

| More than $75 k | 30.43% | 30.17% | 32.71% |

| Finished 4-year college | 35.59% | 36.31% | 32.64% |

| Disabled | 5.65% | 5.85% | 4.80% |

| Currently unemployed | 8.1% | 8.04% | 7.88% |

| Banked | 93.55% | 93.91% | 94.12% |

| Retired | 22.34% | 24.66% | 11.33% |

- Note: 2021 State-by-State National Financial Capability Study.

4 Results

4.1 COVID-19 Households vs. Non-COVID-19 Households on Financial Outcomes

Using t-tests, Table 2 compares the financial outcomes of adults from households who experienced COVID-19 to those who did not. Adults from households directly impacted by COVID-19 fared worse in many areas. In terms of financial perceptions, they were more likely to report financial anxiety, financial fragility, and lower levels of financial wellbeing and financial satisfaction. Those from COVID-19 households were also more likely than those from non-COVID-19 households to report each of the four general objective financial difficulties examined. In fact, adults from COVID-19 households were almost twice as likely to overdraw their checking account or miss a credit card payment than those from non-COVID-19 households. Similarly, these respondents also reported more difficulties with their medical finances and were almost twice as likely to have been laid off or furloughed due to the pandemic. While a slightly higher percentage of adults in COVID-19 households resided in states with lower vaccination rates, adults in households that experienced COVID-19 were as likely to have received a stimulus payment as those not directly impacted by COVID-19. The latter is an expected result since the payments were not tied to contracting the virus.

| Mean comparisons | Full sample | Non-COVID-19 household | COVID-19 household | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Financial perceptions | ||||||

| Financial wellbeing | 52.46 | 53.2 | 16.4 | 49.2 | 14.8 | < 0.001 |

| Financial satisfaction | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| Financial anxiety | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.47 | < 0.001 |

| Financially fragile | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.47 | < 0.001 |

| General obj. financial difficulties | ||||||

| Difficult to pay expenses | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.50 | < 0.001 |

| Spend more than income | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.44 | < 0.001 |

| Overdraw checking account | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| Late credit card payment | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.44 | < 0.001 |

| Medical obj. financial difficulties | ||||||

| Skipped medical treatment | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.49 | < 0.001 |

| Medical debt | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.48 | < 0.001 |

| COVID-19 related controls | ||||||

| Stimulus | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.40 |

| Laid off/furloughed-COVID | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.47 | < 0.001 |

| State vaccination rate | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| N | 22,509 | 4253 | 26,762 | |||

- Note: 2021 State-by-State National Financial Capability Study (using national weights).

Tables 3 and 4 extend this analysis by showing the estimated marginal effects results of ordinary least square (OLS) and linear probability models (LPM) to see if the differences found in Table 2 remain after controlling for key demographic and COVID-19 related factors. We report LPM to facilitate interpretation of results from different models and to facilitate integration in the instrumental variable approach further discussed (Angrist and Krueger 2001). Those who lived in households where a member tested positive for COVID-19 experienced lower financial wellbeing and were more likely to report being financially fragile than those in non-COVID-19 households. However, in this specification, COVID-19 household was not a significant predictor of financial anxiety but, surprisingly, was tied to higher levels of financial satisfaction. Notably, experiencing a COVID-19 lay-off or furlough was associated with poorer financial perceptions.

| (1) OLS | (2) LPM | (3) LPM | (4) LPM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWB | Fin satisfaction | Fin anxiety | Fin fragile | |

| b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | |

| COVID-19 household | −1.38*** (0.25) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) |

| Age | −0.60*** (0.03) | −0.00* (0.00) | 0.01*** (0.00) | 0.00** (0.00) |

| Age-squared | 0.01*** (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) |

| Race/ethnicity ref: white) | ||||

| Black | 2.73*** (0.30) | 0.05*** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.01) |

| Hispanic | 0.80* (0.32) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Asian/Pacific islander | 1.88* (0.78) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.06*** (0.02) | −0.07** (0.02) |

| Other | −0.30 (0.40) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.03) |

| Male | 1.86*** (0.19) | −0.02** (0.01) | −0.06*** (0.01) | −0.07*** (0.01) |

| Married | 3.35*** (0.23) | −0.03*** (0.01) | −0.09*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) |

| Dependents | −3.07*** (0.27) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.03*** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) |

| Income level (ref: less than $25 k) | ||||

| $25–75 K | 2.25*** (0.31) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.11*** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| $75 K+ | 7.41*** (0.38) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.24*** (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.01) |

| College | 2.68*** (0.29) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.11*** (0.00) | −0.02* (0.01) |

| Disabled | −7.14*** (0.55) | 0.08*** (0.01) | 0.25*** (0.01) | 0.09*** (0.02) |

| Unemployed | −4.19*** (0.40) | 0.03** (0.01) | 0.15*** (0.01) | 0.04** (0.01) |

| Banked | 2.48*** (0.40) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.12*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.02) |

| Retired | 2.50*** (0.42) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.06*** (0.02) |

| Stimulus | −2.29*** (0.28) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) |

| Laid off/furlough—COVID | −4.67*** (0.23) | 0.09*** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.13*** (0.01) |

| Constant | 54.73*** (0.75) | 0.30*** (0.04) | 0.44*** (0.03) | 0.60*** (0.04) |

| Observations | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.292 | 0.058 | 0.194 | 0.124 |

- Note: 2021 State-by-State National Financial Capability Study (using national weights). Robust standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult paying expenses | Spending more than income | Overdraw checking account | Late CC payment | Skipped medical treatment | Medical debt | |

| b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | |

| COVID-19 household | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.07*** (0.01) | 0.12*** (0.01) | 0.07*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) |

| Age | 0.00** (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01*** (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00* (0.00) |

| Age-squared | −0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00* (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = white) | ||||||

| Black | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) |

| Hispanic | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.03* (0.02) | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Asian/Pacific islander | −0.05* (0.02) | −0.06*** (0.01) | −0.09*** (0.01) | −0.05** (0.01) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.02) |

| Other | 0.03* (0.02) | −0.00 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Male | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.04*** (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.02** (0.01) |

| Married | −0.07*** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) |

| Dependents | 0.10*** (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.10*** (0.01) | 0.12*** (0.01) | 0.09*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) |

| Income level (ref = less than $25 k) | ||||||

| $25–75 K | −0.07*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| $75 K+ | −0.21*** (0.01) | −0.04*** (0.01) | −0.07*** (0.01) | −0.04** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) |

| College | −0.09*** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.07*** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Disabled | 0.17*** (0.02) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.12*** (0.02) | 0.10*** (0.02) | 0.05* (0.02) | 0.08*** (0.01) |

| Unemployed | 0.11*** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.03** (0.01) |

| Banked | −0.08*** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (.) | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Retired | −0.04** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.03** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) |

| Stimulus | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01* (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Laid off/furlough—COVID | 0.16*** (0.01) | 0.15*** (0.01) | 0.15*** (0.01) | 0.15*** (0.01) | 0.14*** (0.01) | 0.09*** (0.01) |

| Constant | 0.57*** (0.03) | 0.18*** (0.03) | 0.08** (0.03) | 0.29*** (0.03) | 0.27*** (0.04) | 0.30*** (0.04) |

| Observations | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 | 24,089 | 20,759 | 26,095 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.183 | 0.080 | 0.119 | 0.111 | 0.114 | 0.058 |

- Note: 2021 State-by-State National Financial Capability Study (using national weights). Robust standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

In Table 4, we test the association between COVID-19 and a series of general objective financial difficulties after controlling for important variables. Across all six models, households that directly experienced COVID-19 fared worse. Those in COVID-19 households were more likely to have difficulty paying expenses, spend more than income, and have paid a credit card bill late than their non-COVID-19 household counterparts. Those in COVID-19 households result were also 12 percentage points more likely to overdraw a checking account. In the health domain, the chance of skipping a medical treatment and having medical debt was higher among those in COVID-19 households. These findings held even after controlling for demographic and COVID-19 related factors. Being laid-off or furloughed due to COVID-19 was again significantly tied to all negative behaviors examined. While compelling, these results are correlational; next we move to a causal approach.

4.2 Robustness Check

To ensure the robustness of the findings derived from the linear probability model (LPM), we conducted an additional analysis using logistic regression, which is particularly well-suited for binary outcome variables. While the LPM has been criticized for potential limitations, such as producing predicted probabilities outside the [0, 1] range, it remains a valid and interpretable approach for estimating average marginal effects, as argued by Wooldridge (2010, chapter 15). Table 5 presents the odds ratio of the same model specifications as from Table 4. The results from the LPM and the logistic regression were consistent, indicating that the key relationships between the variables remained robust across different modeling approaches. This consistency reinforces the reliability of the findings, regardless of the method used.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult paying expenses | Spend more than Income | Overdraw checking account | Late CC pay | Skipped medical treatment | Medical debt | |

| Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | |

| COVID-19 household | 1.32*** (0.08) | 1.30*** (0.06) | 1.49*** (0.06) | 1.47*** (0.10) | 1.54*** (0.07) | 1.88*** (0.13) |

| Age | 1.03*** (0.01) | 1.00 (0.01) | 1.03** (0.01) | 1.05*** (0.01) | 1.03*** (0.01) | 1.08*** (0.01) |

| Age square | 1.00*** (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00*** (0.00) | 1.00*** (0.00) | 1.00*** (0.00) | 1.00*** (0.00) |

| Race/ethnicity ref: white) | ||||||

| Black | 0.97 (0.05) | 1.33*** (0.06) | 1.34*** (0.07) | 1.43*** (0.08) | 0.69*** (0.04) | 1.15 (0.08) |

| Hispanic | 1.03 (0.07) | 1.01 (0.06) | 0.91 (0.06) | 1.07 (0.10) | 0.89 (0.09) | 0.81* (0.09) |

| Asian/Pacific islander | 0.79* (0.08) | 0.84 (0.10) | 0.71*** (0.07) | 0.72* (0.12) | 0.55*** (0.06) | 0.44*** (0.04) |

| Other | 1.17* (0.09) | 1.03 (0.11) | 1.20 (0.11) | 1.21 (0.14) | 0.97 (0.19) | 1.07 (0.16) |

| Male | 0.78*** (0.03) | 0.89*** (0.03) | 1.02 (0.04) | 0.95 (0.05) | 0.75*** (0.04) | 0.82*** (0.03) |

| Married | 0.69*** (0.03) | 0.81*** (0.03) | 0.98 (0.05) | 0.77*** (0.06) | 0.96 (0.05) | 0.98 (0.04) |

| Dependents | 1.62*** (0.08) | 1.49*** (0.06) | 1.98*** (0.10) | 1.75*** (0.08) | 1.37*** (0.07) | 1.74*** (0.07) |

| Income level (ref: less than $25 k) | ||||||

| $25–75 K | 0.73*** (0.04) | 0.96 (0.04) | 0.90 (0.07) | 0.90 (0.08) | 1.08 (0.06) | 0.98 (0.05) |

| $75 K+ | 0.35*** (0.02) | 0.67*** (0.04) | 0.76*** (0.06) | 0.67*** (0.07) | 0.69*** (0.05) | 0.61*** (0.04) |

| College | 0.64*** (0.03) | 0.95 (0.05) | 0.98 (0.06) | 0.74*** (0.04) | 0.95 (0.05) | 0.59*** (0.02) |

| Disabled | 2.03*** (0.16) | 1.64*** (0.11) | 1.80*** (0.17) | 1.39** (0.17) | 1.37*** (0.12) | 1.80*** (0.14) |

| Unemployed | 1.62*** (0.10) | 1.18* (0.08) | 1.06 (0.07) | 1.08 (0.09) | 1.15 (0.10) | 0.99 (0.06) |

| Banked | 0.70*** (0.05) | 0.97 (0.08) | 1.00 (.) | 0.90 (0.13) | 1.00 (0.11) | 1.02 (0.07) |

| Retired | 0.80** (0.05) | 1.10 (0.10) | 1.15 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.09) | 0.80* (0.07) | 0.89* (0.05) |

| Stimulus | 1.30*** (0.06) | 1.07 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.05) | 1.11* (0.06) | 1.10 (0.06) | 1.49*** (0.10) |

| Laid off/furlough—COVID | 2.13*** (0.10) | 1.70*** (0.08) | 2.20*** (0.10) | 2.26*** (0.13) | 2.46*** (0.10) | 2.19*** (0.11) |

| Constant | 1.12 (0.19) | 0.33*** (0.78) | 0.18*** (0.35) | 0.12*** (0.35) | 0.13*** (0.27) | 0.061*** (0.10) |

| Observations | 26,095 | 26,095 | 24,089 | 20,759 | 26,095 | 26,095 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.146 | 0.061 | 0.112 | 0.129 | 0.090 | 0.120 |

- Note: 2021 National Financial Capability Study (using national weights). Robust standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

4.3 Is There a Causal Relationship Between Testing Positive for COVID-19 and Financial Outcomes?

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First stage COVID | FWB | Financial satisfaction | Financial anxiety | Financially fragile | |

| b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | ||

| State vaccination rate | −0.30*** (0.05) | ||||

| Predicted COVID | — | −12.50* (4.91) | −0.14 (0.21) | 0.03 (0.13) | 0.69*** (0.17) |

| Age | −0.01*** (0.00) | −0.69*** (0.05) | −0.02*** (0.00) | 0.00* (0.00) | 0.01*** (0.00) |

| Age-squared | 0.00*** (0.00) | 0.01*** (0.00) | 0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: white) | |||||

| Black | −0.02 (0.01) | 2.56*** (0.32) | 0.03* (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Hispanic | 0.04** (0.01) | 1.19** (0.42) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.01) |

| Asian/Pacific islander | −0.07*** (0.01) | 0.99 (0.84) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.07** (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) |

| Other | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.46 (0.50) | −0.06*** (0.01) | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Male | 0.02** (0.01) | 2.08*** (0.22) | 0.06*** (0.01) | −0.07*** (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.01) |

| Married | 0.03*** (0.01) | 3.65*** (0.26) | 0.10*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.10*** (0.01) |

| Dependents | 0.04*** (0.01) | −2.55*** (0.35) | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Income level ref: less than $25 k) | |||||

| $25 k–$75 k | −0.01* (0.01) | 2.09*** (0.34) | −0.02* (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.10*** (0.01) |

| $75 k+ | 0.01 (0.01) | 7.52*** (0.41) | 0.13*** (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.01) | −0.24*** (0.01) |

| College | −0.02** (0.01) | 2.43*** (0.34) | 0.09*** (0.01) | −0.02* (0.01) | −0.09*** (0.01) |

| Disabled | −0.00 (0.01) | −7.18*** (0.54) | −0.09*** (0.01) | 0.09*** (0.02) | 0.25*** (0.02) |

| Unemployed | −0.04*** (0.01) | −4.65*** (0.45) | −0.11*** (0.01) | 0.04** (0.01) | 0.18*** (0.02) |

| Banked | 0.03** (0.01) | 2.79*** (0.48) | 0.05** (0.02) | 0.06*** (0.01) | −0.14*** (0.01) |

| Retired | −0.02 (0.01) | 2.32*** (0.40) | 0.10*** (0.01) | −0.06*** (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Stimulus | 0.01 (0.01) | −2.12*** (0.28) | −0.08*** (0.01) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Laid off/furlough—COVID | 0.09*** (0.01) | −3.64*** (0.53) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.13*** (0.01) | −0.02 (0.02) |

| Constant | 0.45*** (0.04) | 58.18*** (1.63) | 0.51*** (0.08) | 0.60*** (0.06) | 0.23*** (0.07) |

| Observations | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 | 26,095 |

| Durbin–Wu–Hausman F statistics | 8.96*** p = 0.0028 | 0.91638 p = 0.3384 | 0.0142 p = 0.9050 | 36.42*** p = 0.0000 | |

- Note: 2021 National Financial Capability Study (using national weights). Robust standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult paying expenses | Spend more than income | Overdraw checking | Late CC payment | Skipped medical treatment | Medical debt | |

| b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | |

| Inst. COVID | 0.39* (0.18) | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.32** (0.10) | 0.28* (0.13) | 1.24*** (0.24) | 1.20*** (0.24) |

| Age | 0.01*** (0.00) | −0.00* (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01** (0.00) | 0.01*** (0.00) |

| Age-square | −0.00*** (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00* (0.00) | −0.00* (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) | −0.00*** (0.00) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: white) | ||||||

| Black | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.04* (0.02) |

| Hispanic | −0.00 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.03* (0.01) | 0.00 (0.02) | −0.07*** (0.02) | −0.07*** (0.02) |

| AAPI | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) |

| Other | 0.04* (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| Male | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.02** (0.01) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.06*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) |

| Married | −0.08*** (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.04*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) |

| Dependents | 0.08*** (0.01) | 0.06*** (0.01) | 0.11*** (0.01) | 0.07*** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) |

| Income level (ref: less than $25 k) | ||||||

| $25 k–$75 k | −0.07*** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| $75 k+ | −0.22*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.04*** (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) | −0.08*** (0.02) | −0.08*** (0.02) |

| College | −0.08*** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.03*** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | −0.05*** (0.01) |

| Disabled | 0.17*** (0.02) | 0.08*** (0.01) | 0.10*** (0.02) | 0.05* (0.02) | 0.08*** (0.02) | 0.12*** (0.02) |

| Unemployed | 0.12*** (0.01) | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.07*** (0.02) | 0.05** (0.02) |

| Banked | −0.09*** (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.06* (0.03) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Retired | −0.04** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.03*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Stimulus | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.04** (0.01) |

| Laid off/furlough due to COVID | 0.13*** (0.02) | 0.10*** (0.01) | 0.13*** (0.01) | 0.12*** (0.02) | 0.09*** (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) |

| Constant | 0.47*** | 0.31*** | 0.20*** | 0.20*** | 0.06 | −0.26** |

| Observations | 26,095 | 26,095 | 24,089 | 20,759 | 26,095 | 26,095 |

| Durbin–Wu–Hausman F statistics | 7.26174*** p = 0.0070 | 0.115234 p = 0.7343 | 6.75186*** p = 0.0094 | 3.91607*** p = 0.0478 | 101.54*** p = 0.0000 | 105.243*** p = 0.0000 |

- Note: 2021 National Financial Capability Study (using national weights). Robust standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

The results from the first stage on Table 6, Column 1 showed that state vaccination rate (the instrumental variable) was significant and negatively associated with the likelihood of a household to test positive (endogenous/treatment variable). An increase of one percentage point in the state vaccination is associated with a three percentage point decrease in COVID infection. A review of postestimation test results shows that state vaccination rate is a robust instrument for predicting testing positive for COVID-19 (Robust F-statistic (1, 50) = 38.04), passing both weak identification test (Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic = 104.46 is above all critical values) and under-identification test (Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic p < 0.0001 rejects the null of under-identification). However, the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test statistic (Deutsch 2012) reported non-significant results in a few cases, showing that endogeneity was not always present (or, at least, failed to find “weak” endogeneity) and the instrumental variable approach does not improve upon a straight OLS model in Columns 3 and 4.

In Table 6, regressions on Columns 3 and 4 did not pass the endogeneity test. In other words, the IV approach, while consistent, is not as efficient as straight OLS in predicting financial satisfaction or financial anxiety. Further, there is no significant relationship found between Predicted COVID and both financial satisfaction and anxiety in those two models. Predicted COVID was not significant in its relationship with financial satisfaction and financial anxiety. Together with Table 3 results, it appears that experiencing the infection had either a minor or no effect on financial satisfaction or financial anxiety. In Columns 2 and 5, results of the second stage IV model show that adults in COVID-19 households experienced lower levels of financial wellbeing and higher levels of financial fragility during the survey period. Both coefficients are stronger than those reported in the OLS in Table 3. Finally, it is also worth noting that the loss of employment due to COVID-19 was related to positive COVID in the first stage and lower financial wellbeing and higher levels of financial anxiety in the second stage.

Table 7 displays the second set of regressions of the 2SLS IV strategy using financial difficulties as the dependent variables of interest to uncover potential impacts of the pandemic in both the wealth and the health of a household.2 Spending more than income was the only outcome that failed the endogeneity test, indicating that the OLS results are more robust. Results show that those in households that experienced COVID-19 reported several worse outcomes on their financial behaviors and medical finances. COVID-19 made it more difficult to pay for expenses and led more respondents to have a late credit card payment or overdraw their checking account. It is also noteworthy that experiencing COVID-19 had a stronger impact on having medical debt and skipping a medical treatment due to cost in the instrumental variable approach. Variation on the sample size for each column is due to some outcome variables being conditional of other survey response (e.g., only those with a credit card can have a late payment). Except for the medical debt outcome, being laid-off or furloughed is tied to worsening financial outcomes. Together, results using the instrumented COVID-19 variable from Tables 6 and 7 points to a potential causal link between contracting the virus and worse self-assessed financial outcomes and are compatible with the previous OLS estimates. Residing in a household in which a member contracted COVID-19 was predictive of a series of detrimental financial outcomes. Being diagnosed with COVID-19 (or being in a household with someone who did) resulted in significantly greater objective general and medical financial difficulties and poorer financial perceptions compared to those not diagnosed with COVID-19. Above and beyond demographic and psychographic characteristics previously tied to poor outcomes, COVID-19 infection emerged as an important characteristic predictive of detrimental outcomes during the pandemic.

5 Discussion

While the current pandemic was felt in some capacity by all US adults, those in households that experienced a COVID-19 infection relatively early in the pandemic fared worse in several key financial outcomes than those who did not. These individuals more frequently lost their jobs, skipped medical treatments due to cost, reported lower levels of financial wellbeing, and were unable to find $2000 to cover an unexpected expense. Other aspects of money management and making ends meet, such as the prevalence of late credit card payments and overdrawing checking accounts, were also affected by COVID-19 infections. Overall, this study found that having COVID-19 early in the pandemic was associated with more negative financial management practices, intentions, and perceptions.

The current study used a representative national survey, controlled for factors such as income and employment, and, most notably, incorporated an instrumental variable approach, using state vaccination rates to explore a potential causal link between COVID-19 infection and a set of financial outcomes. Together, the results indicate that living in a household in which a member was infected with COVID-19 was associated with poorer financial outcomes. More importantly, instrumental variable analyses suggest that being in a household directly impacted by COVID-19 infection may be causally linked to several detrimental financial outcomes. While we found that state vaccination rates are good predictors of a household experiencing COVID-19 and a strong instrument, we recognize that our approach can only alleviate some of the endogeneity and omitted variable bias inherent to these analyses. Our approach is based solely on the variation of the infection related to state-level vaccination rates at the time of the survey collection. This is a limitation given that other potential factors like comorbidities have been shown to impact the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19 (Bajgain et al. 2021).

While our analyses suggest a possible causal relationship between contracting COVID-19 and subsequent financial outcomes, the underlying process is not clear. One possibility is that those who experienced a COVID-19 diagnosis or lived in a household in which someone contracted the disease became more resource constrained, which in turn led to worse financial outcomes. Those experiencing COVID-19 infection or who resided with someone who tested positive were often forced to stay home from work to lessen transmission or provide needed medical care for their loved ones, potentially resulting in loss of employment or earnings. Further, for many mothers of young children, especially, childcare closures impaired their ability to work (Russell and Sun 2020). While limited research exists on the long-term consequences of COVID-19 infection on labor market outcomes, some findings suggest that those experiencing long-term medical effects suffer poorer labor market possibilities (Suran 2023). Additionally, because at the time of data collection, many COVID-19 related work policies required those exposed to COVID-19 to stay home from work, members of a household who dealt with a positive COVID-19 test likely experienced income reductions even if they were not infected or caretakers.

It is also possible that medical expenses related to COVID-19 might have strained these households' budgets, leading to missed payments and more financial anxiety. While the medical sequalae of COVID-19 varied widely across patients, some findings indicate high out-of-pocket medical expenses and adverse financial burdens among those who faced a COVID-19 infection (Becker et al. 2023). In addition, those infected early in the pandemic often experienced social stigma, which could have impacted their employment or job prospects. Loss of employment early in the pandemic was tied to an increased likelihood in the loss of health insurance (Mandal et al. 2022), potentially exacerbating the financial impacts of a COVID-19 diagnosis.

The timing of the survey and the unit of observation must be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. Our experiences with COVID-19 have gone through several stages, from the uncertainties of early days of the pandemic to the current attitude of accepting the virus as part of life with very few restrictions in place. Our data collection occurred during the early to middle stages of the pandemic, when the deadliest strains of the virus had subsided, and vaccines were widely available. Survey collections at earlier or later stages of the pandemic might reveal a different pattern of results on financial outcomes. Additionally, while some survey questions are asked at the household level, others focused on the individual respondent. This is particularly true regarding the job loss variable due to COVID-19, which pertains uniquely to the survey respondent while the question about being infected refers to the household as a whole. There is the possibility that more members of a household experienced job loss due to the pandemic, an event not captured in our data. Further, given that the pandemic took place relatively recently, we cannot be certain about the long-term or permanent implications of the study findings. While a large body of research has examined the effects of the pandemic, examining and understanding long-term financial consequences of those directly impacted by the virus will continue to be an important area of study well into the future.

Results from this study have implications for financial educators and counselors as well as policy makers. Information about the financial strain felt by those directly impacted by COVID-19 early in the pandemic provides insights into the populations in need of resources during times of crisis and can help stakeholders target and tailor financial resources and education. More broadly, financial counselors can help clients better prepare for unexpected life events with negative financial implications. Financial educators also have an important role, bolstering people's financial knowledge and self-efficacy so that they are better prepared to handle these unforeseen financial challenges.

Traditionally, financial counselors have worked with clients on improving crucial financial behaviors from budgeting to building emergency savings. The findings of this study not only reinforce the importance of this current approach but also provide insights into how those directly affected by a pandemic or other global catastrophes might need extra supports. In addition to steering clients to constructive financial behaviors, financial counselors can help clients understand the need for proper medical insurance coverage as part of a broad financial plan. Further, financial counselors' expertise extends beyond just financial topics and can help build clients' financial self-efficacy and reduce financial anxiety using therapy-based strategies.

In a similar vein, our results underscore the importance of policies to improve the financial capability of households. Polices aimed at building household savings, improving money management, providing access to affordable financial services, among others, can help improve financial capability, including the ability to respond to negative financials shocks. When future health shocks occur, special attention might be given to the finances and circumstances of those households impacted early by the disease.

Author Contributions

Nilton Porto: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Gary R. Mottola: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Olivia Valdes: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Appendix A: Variable Description and Coding

| Variable title | Survey item | Original coding | Binary recoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary explanatory variable: COVID-19 | “Have you or anyone living with you tested positive for or been diagnosed with COVID-19?” | Yes/No | Yes = 1 |

| General objective financial difficulties | |||

| Difficulty paying expenses | In a typical month, how difficult is it for you to cover your expenses and pay all your bills? | Very difficult/somewhat difficult/not at all difficult | Very or Somewhat Difficult = 1 |

| Spending more than income | Over the past year, would you say your spending was less than, more than, or about equal to your income? | Spending less than income/spending more than income/spending equal to income | Spending more than income = 1 |

| Overdrawing checking account | Do you overdraw your checking account occasionally? | Yes/No | Yes = 1 |

| Late credit card payment | In the past 12 months, which of the following describes your experience with credit cards? In some months, I was charged a late fee for late payment | Yes/No | Yes = 1 |

| Medical objective financial difficulties | |||

| Medical debt | Do you currently have any unpaid bills from a health care or medical service provider (e.g., a hospital, a doctor's office, or a testing lab) that are past due? | Yes/No | At least one yes = 1 |

| Medical-expense related financial costs |

In the last 12 months, was there any time when you… - Did NOT fill a prescription for medicine because of the cost - Skipped a medical test, treatment or follow-up recommended by a doctor because of the cost - Had a medical problem but did not go to a doctor or clinic because of the cost |

Yes/No | At least one yes = 1 |

| Financial perceptions | |||

| Financial well-being |

- Because of my money situation, I feel like I will never have the things I want in life - I am just getting by financially - I am concerned that the money I have or will save won't last - I have money left over at the end of the month - My finances control my life |

Does not describe me at all to describes me completely = 1–5 Never to always = 1–5 |

Individual scores ranged from 19 to 90 using the CFPB Abbreviated Version Scoring Guide |

| Financial satisfaction | Overall, thinking of your assets, debts and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition? | Likert scale 1–10: where 1 means “not at all satisfied” and 10 means “extremely satisfied.” | 8 or above = 1 |

| Financial anxiety | How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement? Thinking about my personal finances can make me feel anxious | Likert scale 1–7: where 1 = “strongly disagree,” 7 = “strongly agree,” and 4 = “neither agree nor disagree” | 5 or above = 1 |

| Financial fragility | How confident are you that you could come up with $2000 if an unexpected need arose within the next month? | I am certain I could come up with the full $2000/I could probably come up with $2000/I could probably not come up with $2000/I am certain I could not come up with $2000 | I could probably not come up with $2000/I am certain I could not come up with $2000 = 1 |