Evaluation and Treatment of Vulvodynia: State of the Science

Abstract

Vulvodynia affects 7% of American women, yet clinicians often lack awareness of its presentation. It is underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed as vaginitis. The etiology of vulvodynia remains unknown, making it difficult to identify or develop effective treatment methods. The purpose of this article is to (1) review the presentation and evaluation of vulvodynia, (2) review the research on vulvodynia treatments, and (3) aid the clinician in the selection of vulvodynia treatment methods. The level of evidence to support vulvodynia treatment varies from case series to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Oral desipramine with 5% lidocaine cream, intravaginal diazepam tablets with intravaginal transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), botulinum toxin type A 50 units, enoxaparin sodium subcutaneous injections, intravaginal TENS (as a single therapy), multimodal physical therapy, overnight 5% lidocaine ointment, and acupuncture had the highest level of evidence with at least one RCT or comparative effectiveness trial. Pre to posttest reduction in vulvar pain and/or dyspareunia in non-RCT studies included studies of gabapentin cream, amitriptyline cream, amitriptyline with baclofen cream, up to 6 weeks’ oral itraconazole therapy, multimodal physical therapy, vaginal dilators, electromyography biofeedback, hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, cold knife vestibulectomy, and laser therapy. There is a lack of rigorous RCTs with large sample sizes for the treatment of vulvodynia, rendering it difficult to determine efficacy of most treatment methods. Clinicians will be guided in the selection of best treatments for vulvodynia that have the highest level of evidence and are least invasive.

INTRODUCTION

Vulvodynia is chronic vulvar pain of unknown etiology lasting at least 3 months in duration and may be accompanied by other potentially associated factors.1 Vulvodynia can severely impact the lives of women and of individuals assigned female sex at birth. Vulvodynia often affects the ability to have sexual intercourse, devastating intimate relationships.2, 3 Even with adjuvant drugs and opioids, women with vulvodynia reported an average pain intensity score of 6.7 out of 10; 60% of women drank alcohol and 43% used analgesics (including opioids) and alcohol together to reduce their pain.4 Vulvodynia can cause severe chronic pain resulting in physical disability5 and can lead to suicidal ideation.6

Continuing education (CE) is available for this article. To obtain CE online, please visit http://www.jmwhce.org. A CE form that includes the test questions is available in the print edition of this issue.

QUICK POINTS

- ✦ A cotton swab test of the vulva should be performed to diagnose vulvodynia.

- ✦ Clinicians should prescribe treatments that are the least invasive and have the highest level of evidence.

- ✦ There is an urgent need to perform high-quality randomized controlled trials of treatments for vulvodynia.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF VULVODYNIA

The pain of vulvodynia may be described as itching, burning, or stabbing and is often accompanied by dyspareunia.1 Women frequently present with a report of long-standing or recurring vaginitis, with negative laboratory findings, that does not resolve despite receiving a myriad of treatments. Often, women with vulvodynia cannot tolerate anything touching their vulva, such as underclothing or tight-fitting pants, or sitting for prolonged periods, all of which may trigger pain.

HISTORY OF THE PRESENT ILLNESS AND VULVODYNIA

When vulvodynia is suspected, the clinical evaluation focuses on whether women have the following clinical signs and symptoms that may be implicated in, associated with, or lead to the development of vulvodynia: (1) vulvar pain that started while on combined oral contraceptives (COCs), as COCs may promote changes in the vulvar morphology;9 (2) allergic reactions, chronic infections, and yeast infections, as there may be an exaggerated immune response to common pathogens such as Candida albicans;10 and (3) urinary frequency, urgency, hesitancy, feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder, or constipation, which may be signs of hypertonic pelvic floor muscles associated with vulvodynia.1, 11

The clinician should also inquire about other associated factors that can be associated with vulvodynia such as (1) lower back pain, which may constrict muscles, vessels, and nerves with referred pain to the vulva;12 (2) hip, groin, or buttock pain, which may be due to a torn labrum resulting in pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and vulvar pain;13 (3) traumatic childbirth or long bicycle trips, which can lead to pudendal neuralgia and can similarly present with vulvar pain; (4) vulvar burning, soreness, or itching, which may be due to nerve damage that may or may not be associated with low back pain, sciatica, and spinal pathology; and/or (5) genitourinary syndrome of menopause, which may present with vaginal/vulvar pain and/or dyspareunia.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION TO DIAGNOSE VULVODYNIA

Dyspareunia associated with vulvodynia is superficial and occurs at the vaginal introitus, fourchette, and/or outer one-third of the vagina. There is no cervical motion tenderness because the dyspareunia is superficial and not a sign of a peritoneal mass or infection.

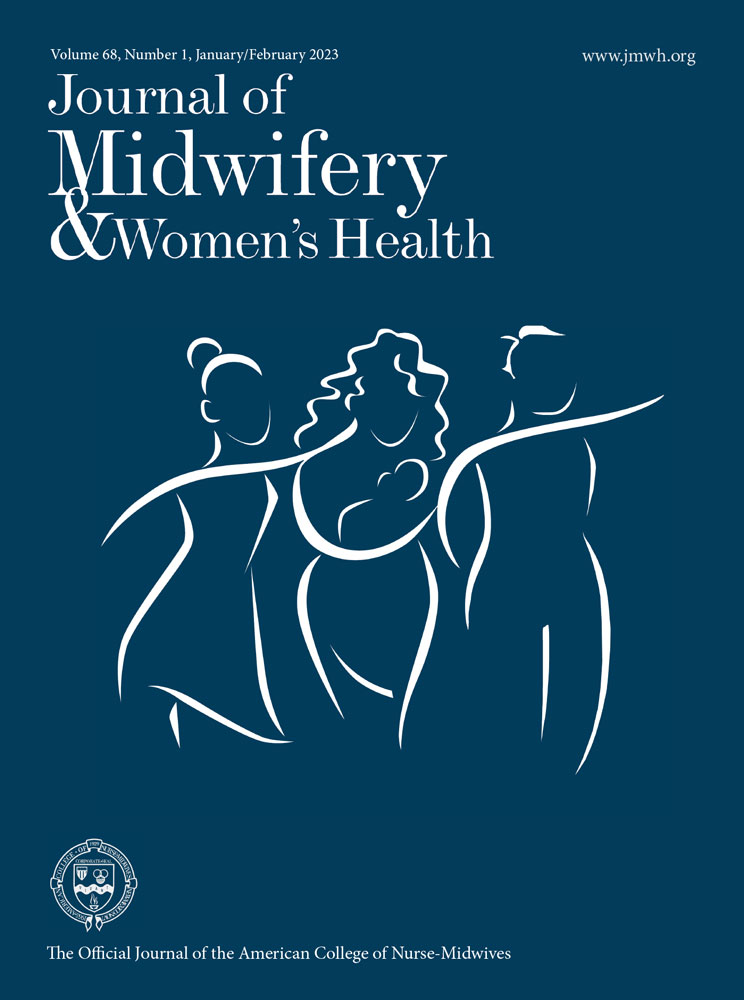

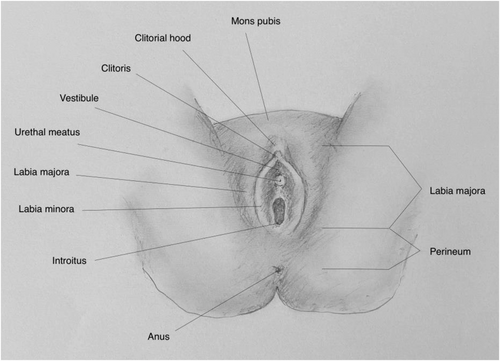

If vulvodynia is suspected, a detailed gynecologic examination of the vulvar anatomy should be performed for allodynia (painful response to an unpainful stimulus) using a cotton swab test (Figure 1). Allodynia, a symptom of neuropathic pain, is caused by a lesion or disease of the nervous system and reflects peripheral or central nervous system changes that may occur in chronic pain conditions.14 The pain of vulvodynia may have a neuropathic component.7, 15 To assess for allodynia, the examiner should perform a cotton swab test (Figure 2). Gentle pressure is applied with a cotton swab starting at the thigh and moving medially to the labia majora, interlabial sulcus, clitoral hood, labia minora, and sites within the vulvar vestibule at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 o'clock.16 Pain is recorded on a 0 to 10 numeric ratings scale (NRS). If the pain is confined to the vulvar vestibule, the diagnosis is localized vestibulodynia; if the pain extends to areas outside the vulvar vestibule, the diagnosis is generalized vulvodynia.

Vulvar Anatomy.

Source: Image courtesy of Pavlina Vagoun-Gutierrez.

Cotton Swab Test to Assess for Vulvar Allodynia.

Source: Image courtesy of Pavlina Vagoun-Gutierrez.

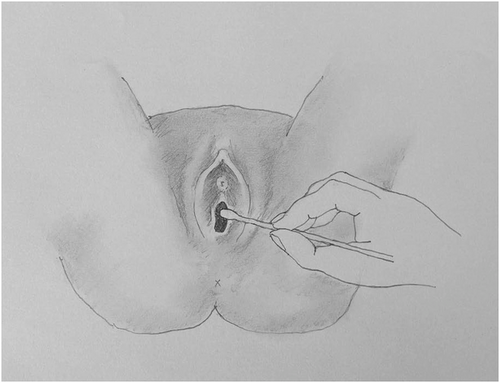

Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is caused by hypertonic muscles with tenderness and can be present in women with vulvodynia.1, 11 Tenderness can be elicited with firm digital pressure to both the levator ani muscle group and the obturator internus in women with vulvodynia. The levator ani muscle group (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and the iliococcygeus) comprises most of the pelvic floor (Figure 3) that supports the bladder and rectum. The obturator internus muscle in the pelvic wall (Figure 3) connects to the pelvic floor via the arcuate tendon levator ani. Both the levator ani and the obturator internus should be palpated by applying even pressure with the index and middle finger of the examining hand during the digital examination, and the pain should be recorded on a 0 to 10 NRS.

Pelvic Floor and Pelvic Wall Musculature

TREATMENTS FOR VULVAR PAIN AND DYSPAREUNIA

The goal of this review is to present the myriad of vulvodynia treatments that patients of midwives are prescribed by other clinicians. All dosages and treatment regimens can be found in Tables 1 to 10. There is a paucity of research on vulvodynia, and many of the studies reviewed are almost 2 decades old with few newer treatment studies that demonstrated efficacy. Our initial search for research articles revealed anecdotal reports and individual case reports of women with vulvodynia, but they were not high quality and were not included in this review. Forty-one studies with the highest level of evidence for each treatment including case series were ultimately included in this review. The level of evidence was evaluated with the rating system from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford (Table 11).17

| Treatment |

Author, Year, Sample Size, Conditions |

Level of Evidence | Study Design, Treatment Groups, Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine |

Zolnoun et al23 2003 N = 61 Vulvar vestibulitis |

2c |

Prospective cohort uncontrolled 5% lidocaine ointment applied generously to the vulvar vestibule and also to a cotton ball that was kept in vulvar vestibule overnight |

Ability to have intercourse increased from 36% to 76% posttreatment (P = .002). Daily vulvar pain (VAS 0-100) reduced from 27.4 to 17.0 (P = .004). Dyspareunia (VAS 0-100) reduced from 76.2 to 37.0 (P = .001). |

| Corticosteroid vs GCBT |

Bergeron et al26 2016 N = 97 PV |

2b |

Uncontrolled randomized trial 2 groups: (1) Hydrocortisone 1% cream every d for 13 wk (2) GCBT, 10 2-h sessions for 13 wk |

Hydrocortisone reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (MPQ PPI, NRS 0-10) from 7.7 (2.1) to 5.6 (3.3) at 13 wk (P < .01) and to 5.9 (3.1) (P < .01) at 6-mo follow-up. GCBT reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 7.3 (2.5) at baseline to 5.5 (2.7) at 13 wk (P < .01) and to 5.2 (2.9) (P < .01) at 6-mo follow-up. GCBT significantly reduced dyspareunia compared with hydrocortisone at 6 mo (P < .01). |

| Gabapentin cream |

Boardman et al28 2008 N = 51 LV, n = 32 GV, n = 19 |

2c |

Retrospective chart review 3 arms: (1) 2% gabapentin cream: LV (n = 9), GV (n = 9) (2) 4% gabapentin cream: LV (n = 7), GV (n = 3) (3) 6% gabapentin cream: LV (n = 16), GV (n = 6) Used for 8 wk but did not state how often was applied |

Mean (SD) vulvar pain (VAS 0-10) in LV reduced significantly from 7.9 (2.0) to 2.7 (1.6) (P < .001). Mean (SD) vulvar pain in GV reduced significantly from 5.8 (1.7) to 2.0 (2.3) (P < .001). Pain improved at least 50% in 80% participants with 29% having complete pain relief in at least 8 wk. Varying doses of gabapentin cream were not accounted for in the statistical analysis. |

| 2% amitriptyline cream |

Pagano and Wong30 2012 N = 150 Vulvodynia |

2c |

Prospective, uncontrolled study 2% amitriptyline cream twice daily for 30 d |

Dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale, 1-3) response: 84 (56%) responded positively to treatment, 15 (10%) participants reported excellent improvement, 44 (29.3%) reported moderate improvement, 25 (16.7%) reported slight but noticeable improvement, 66 (44%) no improvement. 16 participants ceased treatment due to skin irritation. No analysis for significance or posttreatment grading was reported. |

| 2% amitriptyline cream with 2% baclofen cream |

Nyirjesy et al29 2009 N = 38 PV |

2c |

Retrospective study, uncontrolled 2% amitriptyline cream with 2% baclofen cream twice daily for 4-6 wk and up to 33 wk |

Dyspareunia (NRS 1-5) significantly reduced from 4 to 2 (P = .05). |

| Amitriptyline-ketamine gel |

Poterucha et al31 2012 N = 13 Women with genital, rectal, perineal pain |

4 |

Retrospective chart review Amitriptyline-ketamine gel applied to vulva, perineum, rectum, or groin 2-4 times per d Duration unspecified |

Of the 13 women using amitriptyline-ketamine gel, 2 (15%) had no response, 4 (31%) had less than 50% relief, 6 (46%) had 50%-99% relief, and 1 (8%) had complete relief (P = .84). Pain was measured by asking participants which of the categories listed they fell into. No significance testing was reported. |

| Equine conjugated estrogen cream 0.3 mg |

Langlais et al33 2017 N = 20 Vulvodynia |

2b |

Double-blind RCT Equine conjugated estrogen cream 0.3 mg or placebo cream applied at bedtime for 8 wk |

Equine conjugated estrogen significantly reduced global dyspareunia (VAS 0-10) 27% (95% CI, −1% to 55%) (P < .05). Placebo reduced global estrogen 3% (95% CI, −8% to 14%). The difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = .29). Means for each treatment methods were not reported. |

| Topical estradiol 0.03% and testosterone 0.01% cream |

Burrows and Goldstein32 2013 N = 50 Vestibulodynia |

2c |

Retrospective database chart review of 50 consecutive premenopausal women on combined contraceptive pills Topical estradiol 0.03% and testosterone 0.01% cream applied to the vulvar vestibule twice daily for 20 wk |

Cotton swab test vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) reduced from 7.5 to 2 (P = .001). Long-term use of testosterone in premenopausal women has not been evaluated. |

| Nifedipine cream |

Bornstein et al35 N = 30 Localized PV |

2b |

Double-blind RCT 3 arms of 10 participants: (1) 0.2% nifedipine cream (2) 0.4% nifedipine cream (3) Placebo cream Each cream applied 4 times per d for 6 wk |

Nifedipine 0.2% significantly reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (NRS 0-100) from 90.5 (9.0) to 61.9 (34.2) (P = .01). Nifedipine 0.4% significantly reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 92.5 (7.2) to 72.5 (27.6) (P = .06). Placebo significantly reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 88.0 (12.9) to 48.1 (42.8) (P = .04). Treatment methods were not compared with each other. |

- Abbreviations: GCBT, group cognitive behavioral therapy; GV, generalized vulvodynia; LV, localized vulvodynia; MPQ PPI, McGill Pain Questionnaire Present Pain Index; NRS, numeric ratings scale; RCT, randomized controlled trial; PV, provoked vestibulodynia; VAS, visual analog scale.

| Treatment |

Author, Year, Sample Size, Conditions |

Level of Evidence | Study Design, Treatment Groups, Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diazepam intravaginal suppository |

Crisp et al46 2013 N = 21 Hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction |

1b |

Double-blind RCT Diazepam 10 mg or placebo intravaginal suppository at bedtime for 28 d |

Diazepam significantly reduced mean (SD) muscle tone (EMG) from 3.16 (0.88) microvolts to 2.77 (0.91) microvolts (P = .02). Placebo significantly reduced mean (SD) muscle tone from 2.7 (0.328) microvolts to 1.87 (1.3) microvolts (P = .02). The difference between the diazepam and placebo group was not significant. Diazepam significantly reduced mean (SD) worst pelvic pain (VAS 10 cm) from 8.42 (1.02) to 8.5 (1.22) at 2 wk to 8.0 (1.9) at 4 wk. P values not reported. Placebo reduced mean (SD) worst pelvic pain from 8.86 (1.07) to 7.29 (2.14) at 2 wk, and to 6.71 (2.69) at 4 wk. P values not reported. The difference between the diazepam and placebo group was not significant (P = 0.431). |

| Diazepam intravaginal capsules |

Holland et al47 2019 N = 35 Hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction |

1b |

Double-blind RCT 10 mg diazepam capsules or placebo 1-2 times d intravaginally for 4 wk |

Diazepam reduced pelvic pain and levator ani spasm median pain scores (VAS 100 mm) from 59 (95% CI, 50-80) to 50 (95% CI, 20-75). Placebo reduced pelvic pain and levator ani spasm median pain scores from 58 (95% CI, 35-75) to 39 (95% CI, 5-55). Diazepam had 0 median change in the VAS score (100 mm). The placebo group had a 12-point median change. There was not a significant difference in the improvement between the groups (P = .53). |

| Diazepam and intravaginal TENS |

Murina et al48 2018 N = 42 Vestibulodynia |

1b |

Double-blind RCT 10 mg diazepam tablet at bedtime and intravaginal TENS 3 times per wk for 60 d Placebo tablet at bedtime and intravaginal TENS 3 times per wk for 60 d |

Diazepam and TENS reduced mean (SD) cotton swab test vulvar pain (VAS 10 cm) from 7.5 (2) to 4.7 (no SD). Placebo and TENS reduced cotton swab test vulvar pain from 7.2 (1.7) to 4.3 (no SD). No significant difference in pain reduction between groups. P value not provided. Diazepam and TENS reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) from 2.5 (0.5) to 1.6 (no SD). Placebo and TENS reduced mean (SD) pain from 2.0 (1.3) to 1.3 (no SD). Within-group significance testing was not calculated. Diazepam significantly improvement in dyspareunia compared with the placebo group (P < .01). |

- Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Overall, there is great variability in treatments prescribed for vulvodynia. Results from the National Vulvodynia Registry18 showed that a total of 78 different treatments were prescribed to 282 women to reduce their vulvodynia symptoms. Importantly, 72% had been prescribed more than one treatment. Findings highlighted that clinicians may need to prescribe multiple therapies for vulvodynia and that studies may need to replicate real-life conditions.18 Because the etiology of vulvodynia remains unclear, multiple therapies with different mechanisms of action can either potentiate one another or target different pain mechanisms.18

Although the following treatments may have been tested in women with unspecified vulvodynia or for one type of vulvodynia, considering the state of the science, clinicians may consider treating women with either type of vulvodynia. The first 3 treatment groups reviewed are topical, intravaginal, and oral therapies. Topical and intravaginal treatments are localized pharmacologic treatments that are commonly prescribed first. If there is inadequate pain relief, oral therapies are often added. The fourth group of therapies, pelvic floor physical therapy, multimodal therapies, and acupuncture, are minimally invasive and non-pharmacologic. They are prescribed if there is an inadequate response to previously attempted therapies. Unfortunately, third-party insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare reimbursement for these therapies is limited or unavailable, which limits their accessibility.19 The fifth group is injection therapies. They are more invasive and may be prescribed when there is a poor response to the previous therapies. Some clinicians may prescribe them in lieu of pelvic floor physical therapy and particularly acupuncture if they practice within a strict biomedical model. The sixth group, psychological interventions, are presented next, as they are not commonly prescribed because of availability and access issues and are often not considered by the clinician who practices within a strict biomedical model. The seventh group, surgical interventions, are the most invasive therapies and may be prescribed when all other treatment options have failed. The authors reviewed medical cannabis last to update clinicians on progress in this area. There is great interest in treating chronic pain conditions and pelvic pain with medical cannabis.20 The following medications or devices are being used off-label for the treatment of vulvodynia: amitriptyline, desipramine, nifedipine, milnacipran, botulinum toxin type A, low-molecular-weight heparin, and electromyography (EMG) biofeedback.

Topical Treatments

Topical treatments (Table 1) are attractive because they can be applied to the targeted area and have little systemic absorption. Topical treatments for vulvodynia include 5% lidocaine ointment,21-23 capsaicin,24, 25 corticosteroids,26, 27 antiepileptics,28 tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs),29-31 hormones,32, 33 mast cell stabilizers,34 and calcium channel blockers.35

Lidocaine, a local anesthetic, is prescribed as a gel, ointment, or cream and is used to numb the burning pain of vulvodynia. In PV, there is an increase in unmyelinated C-fibers that transmit dull, delayed, diffuse, achy, and burning pain and in calcitonin gene–related peptide that promotes nerve irritation.36, 37 Lidocaine blocks the conduction of C-fibers, but it also can block calcitonin gene–related peptide and calm irritable nociceptors (peripheral sensory neurons) when it is used continuously.38 One large multicenter parallel group randomized trial,22 one randomized controlled trial (RCT),21 and one uncontrolled study23 showed that lidocaine applied to the vulvar vestibule reduced vulvar pain and dyspareunia either alone or with oral desipramine (a TCA) in women with PV.

Capsaicin is the active ingredient found in chili peppers and has been used in many over-the-counter pain preparations. The adverse-effect profile does not warrant prescribing capsaicin for women, as it can cause vulvar burning and can result in vulvar nerve damage.39

One percent hydrocortisone cream decreases inflammation. Long-term use of hydrocortisone causes thinning of skin and vulvar mucosa. In an uncontrolled randomized trial, pre- to post-treatment, 1% hydrocortisone reduced dyspareunia in women with PV, but it did not significantly reduce dyspareunia compared with group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).26 Triamcinolone, a medium potency topical steroid, along with oral amitriptyline, did not reduce vulvar pain in women with PV.27 Even though rapid pain relief is unpredictable and rarely possible,16 there are no data on the long-term use of corticosteroid creams for management of vulvodynia.

Gabapentin, an antiepileptic, exerts its effect on the voltage-dependent calcium ion channels at the postsynaptic terminal of the spinal cord dorsal horn,40 resulting in reduced neuropathic pain. In a retrospective chart review,28 gabapentin cream reduced vulvar pain in PV and generalized vulvodynia pre- to post-treatment. Gabapentin cream must be obtained through a compounding pharmacy. Efficacy of gabapentin cream needs to be tested in future RCTs. Amitriptyline is a TCA that treats chronic neuropathic pain.41 Amitriptyline cream alone30 and amitriptyline cream with baclofen cream, an antispasmotic,29 showed a reduction in dyspareunia in unspecified vulvodynia and in PV. These studies had no control group. Ketamine is used to treat neuropathic pain.42 A case series of 7 women31 showed relief of genital, perineal, and rectal pain after applying amitriptyline-ketamine cream to affected areas. Efficacy of amitriptyline cream, baclofen cream, and amitriptyline-ketamine cream needs to be tested in RCTs.

Conjugated equine estrogen33 and estradiol/testosterone cream32 increase the elasticity, thickness, and moisture of the vulvar epithelium. In a small-sample double-blind RCT of 20 women with PV,33 equine conjugated estrogen showed no reduction in dyspareunia compared with the placebo cream control group. In a retrospective chart review of estradiol/testosterone cream for premenopausal women with PV,32 vulvar pain was reduced pre- to post-treatment. Efficacy of both conjugated equine estrogen cream and estradiol/testosterone cream need to be tested in RCTs. The health effects of long-term hormone creams in premenopausal women have not been studied.

Diazepam Vaginal Suppositories and Tablets

Diazepam is an antispasmodic and anticonvulsant that acts on gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) receptors located in the brain (Table 2).43 GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Diazepam vaginal suppositories and tablets have been prescribed to treat vulvodynia18 and vulvar pain related to hypertonic pelvic floor muscles.11, 43-45 Studies conducted on the use of vaginal diazepam have targeted women with pelvic pain related to hypertonic pelvic floor muscles46-48 but not specifically vulvodynia. There were 2 small-sample double-blind RCTs46, 47 of vaginal diazepam for hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction that showed no reduction in vulvar pain. A third double-blinded RCT48 of diazepam with intravaginal transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo with TENS for PV also showed no reduction in vulvar pain but did show a significant reduction in dyspareunia. All 3 studies were underpowered. Efficacy of diazepam vaginal suppositories and tablets with or without TENS needs to be tested in larger RCTs.

Oral Medications

Oral medications (Table 3) are often prescribed if topical and intravaginal treatments offer incomplete relief. Oral antifungals are initially prescribed for women's common symptoms of vulvar burning and itching with or without confirmatory laboratory testing for vulvar vaginitis. It is only after there is little relief that the clinician may suspect a diagnosis of vulvodynia.49 In an uncontrolled retrospective chart review, women reporting vulvar burning and itching were given 6 to 8 weeks of daily fluconazole with subsequent negative fungal cultures and an insufficient reduction in vulvar pain.49 Women then began a regimen of oral daily itraconazole for 5 to 6 weeks. There was a 70% reduction in vulvar burning and itching. Efficacy of daily fluconazole followed by itraconazole needs to be tested in an RCT. Caution must be exercised if prescribing 5 to 6 weeks of itraconazole therapy for women with vulvodynia that is refractory to fluconazole, even with negative fungal cultures. Because of the risk of hepatotoxicity, liver function needs to be monitored every 3 to 4 weeks during itraconazole therapy.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole and itraconazole |

Rothenberger et al49 2021 N = 106 PV |

2c |

Retrospective cohort chart review with no control 200 mg fluconazole daily for 6-8 wk. If there was insufficient reduction of vulvar pain and a negative fungal culture, itraconazole therapy 200 mg twice daily was used for at least 5 wk Due to risk of hepatotoxicity; liver function tests were carried out every 3-4 wk during treatment period |

Mean (SD) decrease in cotton swab test vulvar vestibule pain (NRS 0-10) from baseline to 9 wk was 60.7% (39%). 66.0% of participants had significant pain reduction of >50% reduction (P = 0.043). The optimal window for pain improvement was 5-6 wk with an average reduction of 69.6%. 5 women discontinued, 3 due to gastrointestinal adverse effects, 1 due to elevated liver function, 1 after seizure during treatment. |

| Oral desipramine with topical lidocaine vs oral desipramine only vs topical lidocaine only |

Foster et al21 2010 N = 133 PV |

1b |

Double-blind placebo RCT 4 arms, 12 wk: (1) 25 mg oral desipramine daily with a 25 mg increase every wk until 150 mg daily; 5% lidocaine cream applied 4 times daily to painful areas (2) Placebo desipramine and placebo topical lidocaine (3) Oral desipramine protocol with placebo topical lidocaine (4) Placebo desipramine with topical lidocaine protocol |

Desipramine with lidocaine cream reduced tampon test pain (NRS 0-10) significantly by 36% (t = −2.13; P = .04). Oral desipramine and placebo topical lidocaine reduced pain by 24% (t = 0.90; P = .37). Placebo desipramine and topical lidocaine cream reduced pain by 20% (t = 1.27; P = .21). Placebo oral desipramine and placebo topical cream reduced pain by 33% (no t-score provided). There was no significant reduction in pain when interventions were used singularly. Pain scores were not provided. |

| Oral amitriptyline vs oral amitriptyline and topical triamcinolone |

Brown et al27 2009 N = 43 Vulvodynia |

2b |

RCT (1) Oral amitriptyline: 10-20 mg daily (2) Oral amitriptyline: 10-20 mg daily and 0.1% topical triamcinolone at bedtime (3) Self-management control 12-wk intervention |

Oral amitriptyline reduced mean (SD) vulvar pain (MPQ PPI, 0-5) by 1.4 (1.6) points. Oral amitriptyline and triamcinolone reduced mean (SD) pain by 0.8 (1.9) points. Self-management reduced mean (SD) pain by 0.7 (1.6) points. No significant difference between self-management, oral amitriptyline, and oral amitriptyline and triamcinolone at 12 wk. No P values reported. |

| Amitriptyline vs amitriptyline and PT |

Bardin et al45 2020 N = 57 PV |

2b |

RCT (1) Daily home PT and amitriptyline 25 mg at bedtime for 8 wk (2) Amitriptyline 25 mg at bedtime for 8 wk |

Amitriptyline only reduced cotton swab test mean (SD) vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) significantly from 6.6 (2.0) to 4.4 (2.5) (P = .018). PT and amitriptyline reduced mean (SD) vulvar pain significantly from 6.3 (2.0) to 2.9 (2.06) (P < .001). Amitriptyline only increased mean (SD) pain during intercourse (NRS 0-10) from 2.4 (2.6) to 2.5 (2.5) (P = .91). PT and amitriptyline reduced mean (SD) pain during intercourse significantly from 7.5 (3.1) to 3.1 (2.6) (P < .001). |

| Milnacipran |

Brown et al50 2015 N = 22 PV |

2c |

Clinical intervention with no control group Milnacipran from 12.5 to 200 mg/d over 6 wk followed by 6 wk on maximum dose |

Milnacipran reduced mean (SD) pain (MPQ PRI 0-45) significantly from 20 (8.9) to 12.3 (13.3) (P = .001). Mean (SD) coital pain (NRS 0-10) reduced from 6.94 (2.51) to 3.43 (2.82) (P = .001). |

| PEA, transpolydatin, and TENS vs TENS |

Murina et al52 2013 N = 20 Vestibulodynia |

1b |

RCT (1) PEA 400 mg and transpolydatin 40 mg twice daily with intravaginal TENS self-administered at home for 60 d (2) Placebo and intravaginal TENS self-administered at home for 60 d |

PEA, transpolydatin, intravaginal TENS significantly reduced mean (SD) pain intensity (VAS 10 cm) from 5.8 (1.1) to 2.2 (1.6) (P < .05). Placebo and intravaginal TENS significantly reduced mean (SD) pain intensity from 6.2 (1.1) to 2.3 (1.5) (P < .05). No significant reduction between groups (P = .57). PEA, transpolydatin, intravaginal TENS reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) from 2.8 (0.4) to 1.0 (0.9); not significant; no P value provided. Placebo and intravaginal TENS reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 2.6 (0.5) to 1.1 (0.9); not significant; no P value provided. No significant reduction between groups (P = .38). PEA and transpolydatin found to be more effective than placebo in cases with more recent onset (VAS, P < .01, Marinoff P < .01). |

| Gabapentin |

Brown et al89 2018 N = 89 PV |

1b |

Double-blind RCT with crossover over 16 wk Gabapentin 1200-3000 mg/d or placebo, increasing dose over 4 wk followed by 2 wk maintenance, then 2 wk taper down (wash out); then switch to other therapy |

Gabapentin reduced mean dyspareunia (tampon test, NRS 0-10) by 3.9 (95% CI, 3.4-4.5) points. Placebo reduced mean pain scores by 4.3 (95% CI, 3.7-4.9). Difference −0.3 (95% CI, −0.7 to 0.1) (P = .07). |

| Gabapentin |

Bachmann et al90 2019 N = 66 PV |

1b |

Double-blind RCT with crossover 16-wk study Gabapentin 1200-3000 mg/d or placebo, increasing dose over 4 wk followed by 2 wk maintenance, then 2 wk taper down (wash out); then switch to other therapy |

Gabapentin did not significantly improve dyspareunia (FSFIp 0-5) (P = .23). |

- Abbreviations: FSFIp Female Sexual Function Index Sensory Pain Subscale; MPQ PPI, McGill Pain Questionnaire Present Pain Index; MPQ PRI, McGill Pain Questionnaire Pain Rating Index; NRS, numeric ratings scale; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; PT, physical therapy; PV, provoked vestibulodynia; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Oral TCAs, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and antiepileptics are prescribed for chronic neuropathic pain. TCAs, SNRIs, SSRIs, and antiepileptics can reduce neuropathic pain by influencing neurotransmitters affecting pain in the central and peripheral nervous systems.41 Their ability to reduce pain in women with vulvodynia has been inconsistent.21, 27, 45, 50

One 4-arm double-blind RCT used oral desipramine (a TCA) and 5% lidocaine cream for dyspareunia.21 Desipramine compared with placebo did not reduce dyspareunia, but desipramine with 5% lidocaine did reduce dyspareunia in women with PV. One RCT using amitriptyline alone and amitriptyline with triamcinolone cream did not reduce vulvar pain in women with PV.27 A second RCT of amitriptyline, and amitriptyline with physical therapy,45 showed amitriptyline alone reduced vulvar pain but not dyspareunia. Amitriptyline with physical therapy reduced vulvar pain and dyspareunia.

There is only one study that used SNRIs and no studies that used SSRIs for vulvodynia even though they are commonly prescribed.18, 50 Milnacipran (an SNRI) reduced pain and dyspareunia in one uncontrolled study.50 Efficacy of SSRIs and SNRIs need to be tested in RCTs.

Women with vulvodynia can have an increased number of vulvar mast cells, which are part of the inflammatory response.51 Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is an endogenous fatty acid amide that targets mast cell infiltration, and trans-polydatin is a natural antiinflammatory compound found in foods.52 An RCT of PEA with trans-polydatin and intravaginal TENS compared with oral placebo and intravaginal TENS (Figure 4) showed no reduction of vulvar pain and dyspareunia except for in newly diagnosed women.52 Both PEA and trans-polydatin are natural food supplements. There is evidence to support the use of PEA and TENS only in women who are newly diagnosed with vulvodynia.

Intravaginal Probe Used with Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation.

Source: Vaginal probe courtesy of BEACMED s.r.l, Portalbera (PV), Italy.

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy and Multimodal Therapy

Pelvic floor physical therapy is used to treat pelvic floor dysfunction and hypertonic pelvic floor muscles associated with vulvodynia (Table 4).45, 53, 54 Pelvic floor physical therapy includes dilators, EMG biofeedback, and TENS.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilators |

Murina et al55 2008 N = 15 Vestibulodynia |

2c |

Uncontrolled observational prospective 4 sizes of sequentially larger vaginal dilators over 8 wk |

Mean (SD) dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) reduced significantly from 2.2 (0.4) to 1.1 (0.9) (P < .001). |

| EMG biofeedback vs topical lidocaine |

Danielsson et al58 2006 N = 46 Vulvar vestibulitis |

2b |

Randomized prospective cohort study 2 arms, no control group: (1) EMG biofeedback 3 times per d with intravaginal probe (2) 2% topical lidocaine gel applied 5-7 times per d for 2 mo, then 5% topical lidocaine ointment applied 5-7 times per d for 4 mo Follow-up at 6 mo and 12 mo |

Both treatments showed significant improvement in vestibular pressure pain threshold (grams) (biofeedback group P = .02, lidocaine group P = .007) and pain threshold intensity (VAS 0-100) (biofeedback group P = .001, lidocaine group P = .002) at 12 mo. Neither the pain nor pain intensity had significant improvement when compared with one another. Compliance for 3 sessions of biofeedback per d was low. |

| TENS |

Murina et al60 2008 N = 40 Vestibulodynia |

1b |

Double-blind placebo controlled RCT 2 arms: (1) TENS 2 times per wk with electrodes placed at the introitus for 10 wk (2) TENS placebo 2 times per wk with electrodes placed at the introitus for 10 wk 60- and 90-d follow-up |

TENS reduced mean (SD) vulvar pain (VAS 0-10) significantly from 6.2 (1.9) to 2.1 (2.7) (P = .004) at 60 d posttest, and to 2.8 (2.5) (P = .004) at 90 d posttest. TENS placebo reduced mean (SD) vulvar pain from 6.7 (2.0) to 5.7 (2.2) at 60 d posttest, and to 5.6 (2.1) at 90 d posttest. Placebo pain reductions were statistically significant; no P value provided. Between-group comparisons were not conducted. TENS reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) significantly from 2.7 (0.4) to 1.1 (0.9) (P = .001) at 60 d posttest, and to 1.1 (0.9) (P = .001) at 90 d posttest. TENS placebo reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 2.7 (0.4), to 2.4 (0.8) at 60 d posttest, and to 2.4 (0.8) at 90 d posttest. Neither reduction in pain due to placebo was significant; P values not provided. Between-group comparisons were not conducted. |

| Multimodal approach |

Brotto et al2 2015 N = 116 PV |

2b |

Uncontrolled prospective study Multimodal approach Each participant received (1) 2 educational informational sessions on PV, (2) 3 educational psychological sessions, (3) 3 pelvic floor education sessions including home exercises and in office biofeedback, (4) final session with gynecologist to discuss skills acquired, referrals needed, and community resources All sessions over 10-12 wk |

Dyspareunia (VAS 0-10) reduced significantly from pretreatment to posttreatment (β = −5.3, P < .001). |

| Multimodal physical therapy vs lidocaine |

Morin et al22 2021 N = 212 PV |

2c |

Multicenter parallel group randomized trial 1:1 (1) Multimodal physical therapy: (a) education, (b) pelvic floor muscle exercises with biofeedback, (c) manual therapy, (d) dilation (2) Overnight lidocaine 5% ointment vestibule with gauze soaked in lidocaine applied to vulvar vestibule Baseline, posttreatment (10 wk), and 6-mo follow-up |

Physical therapy significantly reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia (NRS 0-10) from 7.3 (0.2), to 2.7 (0.2) at 10 wk (P < .01), with results maintained through follow-up at 6 mo 3.0 (0.2). Overnight lidocaine significantly reduced mean (SD) dyspareunia from 7.3 (0.2), to 4.5 (0.2) at 10 wk (P < .01), with results maintained through 6-mo follow-up 4.8 (0.2). Physical therapy significantly reduced dyspareunia compared with lidocaine from baseline to 10 wk, and through follow-up at 6 mo (P < .001). |

- Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; NRS, numeric ratings scale; PV, provoked vestibulodynia; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Dilators desensitize the vulva to touch and pressure and stretch hypertonic pelvic floor muscles and the vagina.54 One uncontrolled prospective study showed dilators55 reduced dyspareunia. Dilators as a standalone therapy are a cost-effective, self-administered at home, and noninvasive intervention with a low adverse-effect profile. Efficacy of dilators as a single therapy needs to be tested in RCTs.

EMG biofeedback offers women immediate visual feedback regarding their pelvic floor muscle tonus. By watching a monitor, women learn how it feels when their pelvic floor muscles contract and relax. Three uncontrolled studies of EMG biofeedback56-58 all showed a reduction in vulvar pain. EMG biofeedback is a noninvasive intervention with a low adverse-effect profile. Efficacy of biofeedback needs to be tested in RCTs.

TENS inhibits pain by (1) blocking pain signals at the injury from being propagated to larger afferent fibers in the central nervous system for processing (gate control theory)59 and (2) stimulating the release of endogenous opioids.60 A double-blind placebo RCT compared intravaginal TENS with a TENS sham.60 TENS significantly reduced pain and dyspareunia.

There are 2 studies that have tested an interprofessional multimodal combined therapy approach. In the first study, which was uncontrolled,2 116 women received educational sessions on PV, psychology, pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback as well as a session with a gynecologist. Findings showed a significant decrease in dyspareunia at 3 months. In the second, a large multicenter parallel group randomized trial,22 212 women with PV were randomized to either multiple modality physical therapy (physical therapy, education, pelvic floor exercises with biofeedback, manual therapy, and dilation) or overnight 5% lidocaine ointment applied to the vulva. Findings showed a significant reduction in dyspareunia in both groups that was maintained at 6 months. Participants in the multimodal physical therapy group had significant improvement in all the measured outcomes; moreover, there was a significant reduction in pain and treatment effectiveness in women who received multimodal physical therapy compared with lidocaine.

Acupuncture

Women often turn to acupuncture to relieve vulvodynia (Table 5).16 According to acupuncture theory, when the vital energy (qi) is blocked in vulvodynia, there is resultant pain and heat (felt as vulvar burning, stinging, and/or itching).61 Acupuncture is applied to acupoints on the abdomen, suprapubically, and the extremities, but not directly to the vulva. Acupuncture moves blocked qi, relax pelvic floor muscles, and reduce pain and heat in the vulva. The physiologic mechanisms of acupuncture include increased release of mu opioids62 and beta endorphins, both important in reducing the sensation of pain.63 Acupuncture in an RCT64 significantly reduced vulvar pain and dyspareunia in vulvodynia compared with a waitlist control. This standardized acupuncture guideline is currently being replicated in a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded double-blind sham placebo–controlled RCT of acupuncture for vulvodynia;65, 66 results will be reported in 2023. Acupuncture is a minimally invasive, non-pharmacologic intervention with a low adverse-effect profile.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture |

Schlaeger et al64 2015 N = 36 Vulvodynia |

1b |

RCT 1:1 Standardized acupuncture protocol twice per wk for 5 wk, total 10 sessions compared with waitlist control group Women in the waitlist control group received 10 sessions free acupuncture upon study completion |

Acupuncture reduced mean (SD) pain (SF-MPQ, VAS 0-10) from 5.6 (1.9) to 2.7 (1.7). Usual care control reduced mean (SD) pain from 5.7 (2.3) to 5.1 (2.9). Acupuncture significantly reduced pain compared with usual care (P = .003). Acupuncture improved mean (SD) dyspareunia (FSFIp, 0-5) from 1.9 (1.3) to 3.2 (1.9). Usual care control improved dyspareunia from 1.7 (1.8) to 1.4 (1.8). Acupuncture significantly improved care compared with usual care (P = .003). |

- Abbreviations: FSFIp, Female Sexual Function Index Sensory Pain Subscale; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SF-MPQ, Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire; VAS, visual analog scale.

Injections

Botulinum toxin type A injections67-69 and low-molecular-weight-heparin70 have been used to treat vulvodynia (Table 6). Botulinum toxin type A prevents the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction resulting in muscle paralysis and has been used in the prevention of migraine headaches.71 Botulinum toxin type A is injected into trigger points (painful areas on the vulvar vestibule) and/or into hypertonic pelvic floor muscles. Out of 3 studies,67-69 one double-blind RCT67 showed that 50 units of botulinum toxin type A reduced dyspareunia but not vulvar pain in women with vulvodynia. The second double-blind RCT69 showed no difference in vulvar pain between botulinum toxin type A 20 units and placebo at 3 and 6 months. The third study was uncontrolled.68 Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A 50 units needs to be replicated in a larger RCT.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botulinum toxin type A |

Diomande et al67 2019 N = 33 PV |

1b |

Double-blind RCT 3 arms: (1) Botulinum toxin type A 50 units (2) Botulinum toxin type A 100 units (3) Saline injections 1 injection subcutaneously into the dorsal vulvar vestibulum Pain assessed at 3 mo |

Botulinum toxin type A 50 units reduced mean (SD) pain (VAS 0-10 cm) from 6.6 (2.0) to 0.2 (2.6) but not significantly more than the placebo (P = .4). Botulinum toxin type A 100 units reduced cotton swab test mean (SD) vulvar pain from 7.4 (1.9) to 6.0 (1.8) but not significantly more than the placebo (P = .2). Saline reduced mean (SD) pain from 7.0 (2.2) to 0.5 (1.3). Botulinum toxin type A 50 units reduced (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) dyspareunia from 2.0 to 1.5, significantly more than the placebo (P = .03). Botulinum toxin 100 units reduced dyspareunia from 2.5 to 1.5, but not significantly more than the placebo (P = .3). Saline dyspareunia pain score remained the same from before to after treatment: 2.0. |

| Botulinum toxin type A diluted in saline |

Petersen et al69 2009 N = 60 PV |

1b |

Double-blind RCT 1 injection in to bulbospongiosus of botulinum toxin type A 20 units diluted in 0.5 mL normal saline or 0.5 mL placebo saline 6-mo follow-ups |

Botulinum toxin 20 units and the placebo significantly reduced pain (VAS 10 cm) from baseline (botulinum toxin type A, 7.5; placebo, 7.6) to 6 mo (6-mo values not provided) (P < .001). There was not a significant difference between improvement in the botulinum toxin 20 units group compared with the placebo group (P = .984). |

| Botulinum toxin type A |

Hansen et al68 2019 N = 109 PV |

2b |

Prospective uncontrolled trial 100 units botulinum toxin type A 50 units to each side |

Cotton swab test vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) (n = 63) reduced significantly from 6.8 to 5.5, at 6 mo (P < .01). Dyspareunia (NRS 0-10) (n = 44) reduced significantly from 7.8 to 5.8 (P < .01). 30 participants dropped before follow-up. |

| Enoxaparin |

Farajun et al70 2012 N = 40 PV |

1b |

Single-blinded RCT Self-administered 40 mg enoxaparin (low-molecular-weight heparin) or placebo saline self-administered subcutaneously to the abdomen every d for 90 d Pain measured at 90 and 180 d Enoxaparin sodium requires daily self-injections and may promote bruising and bleeding |

Enoxaparin reduced cotton swab test vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) from 8.2 to 6.25 at end of treatment and to 5.8 at 180-d follow-up. Saline reduced pain from 7.5 to 6.6 at end of treatment However, pain increased to 6.8 at 180-d follow-up. Enoxaparin reduced pain significantly compared with saline from baseline to 180-d follow-up (P = .004). Enoxaparin sodium significantly reduced pain during intercourse (percentage reduced) 28.9% at 90 d (P = .057). Placebo reduced pain by 4.4%; P value not provided. |

- Abbreviations: NRS, numeric ratings scale; PV, provoked vestibulodynia; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VAS, visual analog scale.

Low-molecular-weight heparin reduces pain by increasing blood flow to the vulvar stroma, reducing the release of nerve growth factor from mast cells, and decreasing inflammation.70 In a single-blind RCT,70 enoxaparin sodium administered subcutaneously to the abdomen by self-injection every day for 90 days showed a significant reduction in vulvar pain at 180 days compared with placebo.70 Coagulation monitoring is not necessary with low-molecular-weight heparin, but women should be taught self-monitoring for bleeding and bruising. Evidence suggests low-molecular-weight heparin be used up to 90 days’ duration.

Psychological Interventions

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT is used as a non-pharmacologic option for the management of PV (Table 7).72 There were 2 uncontrolled studies of group CBT and other psychological modalities.73, 74 The first showed a reduction of dyspareunia in women with PV receiving group CBT.73 The second showed a non-significant reduction in vulvar pain on a scale of 0 to 6, from 2.6 to 1.5 at 10 weeks posttreatment, and to 1.3 at one year posttreatment in unspecified vulvodynia compared with supportive psychotherapy.74 There were 5 separate randomized uncontrolled studies of CBT with non-psychological interventions: 1% hydrocortisone cream,26 physical therapy,72 vestibulectomy plus EMG biofeedback,56, 57 and 5% lidocaine.75 In the first uncontrolled randomized study, CBT significantly reduced dyspareunia compared with 1% hydrocortisone cream at 6 months.26 In the second uncontrolled randomized study, CBT and physical therapy72 showed a decrease in vulvar pain and dyspareunia. Physical therapy significantly reduced vulvar pain more than CBT, but there was no significant difference between CBT's and physical therapy's reduction in dyspareunia. In the third uncontrolled randomized study, CBT compared with vestibulectomy compared with EMG biofeedback56, 57 showed reduced vulvar pain and dyspareunia in all 3 groups at 6 months for women with PV. In a continuation of the same study at 2.5 years, vestibulectomy had a greater reduction in vulvar pain, but all groups had a sustained reduction in pain. Both CBT and vestibulectomy reduced dyspareunia at 2.5 years. However, women in the CBT group were significantly more satisfied with their treatment than women who received vestibulectomy, suggesting that women may prefer less invasive treatments. In the fourth uncontrolled randomized study, both cognitive behavioral couples therapy and 5% overnight lidocaine ointment75 reduced dyspareunia at 12-week and 6-month follow-up in women with PV, but treatment groups were not compared with one another. Use of CBT can be limited by a lack of CBT providers and access to CBT for women with low income. Efficacy of CBT needs to be tested in RCTs.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-gCBT vs education support group |

Guillet et al73 2019 N = 32 Localized provoked vulvodynia |

2b |

Randomized uncontrolled prospective cohort study 2 arms: (1) M-gCBT once per wk for 8 wk (2) Education support group therapy, 3 sessions in 8 wk |

Education support group's dyspareunia (tampon test, Likert 0-10) reduced significantly from baseline to 3 mo (P = .012), and from baseline to 6 mo (P < .001). M-gCBT group's dyspareunia reduced significantly from baseline to 3 mo (P < .001), and from baseline to 6 mo (P < .001). There was no significant difference between dyspareunia scores in the education support group and M-gCBT group (P = .427). |

| CBT |

Masheb et al74 2009 N = 50 Vulvodynia |

2b |

Randomized uncontrolled prospective cohort study CBT 1 session/wk for 10 wk Supportive psychotherapy 1 session/wk for 10 wk Baseline, posttreatment at 10 wk and 3, 6, and 12-mo follow-up |

CBT reduced mean (SE) vulvar pain severity (Yale–New Haven Multidimensional Pain Severity scale, 0-6) from 2.6 (0.2) to 1.5 (0.3) at 10 wk posttreatment, and to 1.3 (0.3) at 1 y posttreatment. Supportive psychotherapy reduced mean (SE) vulvar pain severity from 3.0 (0.6) to 1.9 (0.3) at 10 wk posttreatment, and 1.3 (0.3) at 1 y posttreatment. There was not a significant difference improvement of vulvar pain severity between groups at 1 y (F = 2.63 P = .053). |

| CBT vs PT |

Goldfinger et al72 2016 N = 20 PV |

2b |

Randomized uncontrolled CBT or PT 8 1.5-h one-on-one sessions of CBT or PT and homework activities Pain measured at baseline, posttreatment, and 6-mo follow-up |

CBT reduced cotton swab test mean (SD) vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) from 3.94 (2.3) at pretreatment to 3.26 (2.69) at posttreatment (P = .144) and 2.62 (2.88) at follow-up (pretreatment to follow-up, P = .009). PT significantly reduced cotton swab test mean (SD) vulvar pain from 4.16 (1.53) at pretreatment to 1.28 (1.05) at posttreatment (P = .001) and 1.86 (2.22) at follow-up (pretreatment to follow-up, P = .008). PT reduced average cotton swab test vulvar pain significantly compared with CBT (P = 0.009). CBT significantly reduced mean (SD) pain intensity with intercourse (dyspareunia) from 5.2 (1.4) to 2.6 (1.43) at posttreatment (P = .004) to 2.1 (1.37) at 6 mo (pretreatment to follow-up, P = .001). PT significantly reduced mean (SD) pain intensity with intercourse from 5.05 (1.86) at pretreatment to 2.7 (2.36) at posttreatment (P = .004) to 2.4 (2.63) at follow-up (pretreatment to follow-up, P < .001). There was not a significant difference between the 2 groups; P value not provided. |

|

CBCT Lidocaine |

Bergeron et al75 2021 N = 108 women and their partners PV |

2b |

Randomized uncontrolled trial 2 arms: (1) CBCT 1, 75-min session per wk for 12 wk (2) 5% lidocaine ointment overnight to vulvar vestibule |

CBCT reduced mean (SD) pain intensity during intercourse (NRS 0-10) from 6.8 (1.8) at baseline to 4.7 (2.2) at 12 wk posttreatment, and to 4.5 (2.5) at 6 mo posttreatment. 5% overnight lidocaine reduced mean (SD) pain intensity during intercourse from 6.5 (1.8) at baseline to 4.7 (2.2) at 12 wk posttreatment, and to 4.7 (2.6) at 6 mo posttreatment. No significant difference between the treatment effect of CBCT vs 5% overnight lidocaine. |

| Hypnosis |

Pukall et al76 2007 N = 8 Vulvar vestibulitis |

2c |

Case series with no control group Hypnotherapy, 6 sessions Follow-up at 1 mo and 6 mo posttreatment |

Cotton swab test vulvar pain scores (NRS 0-10) significantly reduced from pretreatment to 1 and 6 mo posttreatment (P ≤ .01). Cotton rub test vulvar pain scores (NRS 0-10) significantly reduced from pretreatment to 6 mo (P ≤ .05) but not pretreatment to 1 mo posttreatment. Intercourse pain measured (MPQ PPI, 0-5) improved significantly between baseline and 1-mo follow-up, and baseline and 6-mo follow-up (P = .006); and intercourse-/nonintercourse-related pain frequency (P = .03). Nonintercourse vulvar pain severity MPQ PPI improved significantly between baseline and 1-mo follow-up, and baseline and 6-mo follow-up (P = .002). |

- Abbreviations: CBCT, cognitive behavioral couples therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; M-gCBT, mindfulness-based group cognitive behavioral therapy; MPQ PPI, McGill Pain Questionnaire Present Pain Index; NRS, numeric ratings scale; PT, physical therapy.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis for vulvodynia has only been evaluated in one uncontrolled study76 that showed a significant reduction of vulvar pain and dyspareunia (Table 7). Because hypnosis is a noninvasive therapy for the treatment of chronic pain conditions,77 it may be considered a viable treatment option for women with PV. Efficacy of hypnosis needs to be tested in RCTs.

Surgical Interventions

Cold Knife Vestibulectomy and Laser Therapy

It is unknown why vestibulectomy reduces vulvar pain and dyspareunia (Table 8). Two studies56, 57, 78 on vestibulectomy found significant reduction in vulvar pain and dyspareunia, one of which was compared with group CBT and EMG biofeedback56 that continued 2.5 years postoperatively.57 Twenty-seven percent of women declined to participate after they had been randomized to the vestibulectomy group, suggesting that not all women may view vestibulectomy as an acceptable treatment option.56 Vestibulectomy is not widely used because of limited patient acceptability. Because of its invasive nature, vestibulectomy should be considered a treatment of last resort.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold knife vestibulectomy vs GCBT vs EMG biofeedback |

2001 and 2008 N = 78 Vulvar vestibulitis |

2b |

2001: Prospective uncontrolled randomized trial 3 arms: (1) Cold knife vestibulectomy with a 6-wk postoperative visit (2) GCBT, 8 sessions over 12 wk (3) Surface EMG biofeedback 8 sessions over 12 wk with twice daily practice sessions All treatment methods had a posttreatment and 6-mo follow-up 2008: 2.5-y follow-up study conducted in 2008 |

2001: 7 of 26 (27%) of women randomized to the vestibulectomy group declined participation (P < .01). All 3 treatment groups had significant reduction in cotton swab test vulvar pain (average of 2 test scores, scale not provided) at posttreatment, 6 mo, and 2.5 y (P < .01). Vestibulectomy reduced vulvar pain by 70%, GCBT by 28.6%, and biofeedback by 23.7%. Vestibulectomy reduced vulvar pain significantly from baseline to posttreatment, and through 6-mo follow-up compared with GCBT and to EMG biofeedback (P < .01). All 3 groups had significant improvement in pain intensity during intercourse (NRS 0-10) (P < .01). Vestibulectomy reduced intercourse pain by 52.5%, GCBT by 37.5%, and biofeedback by 35%. Vestibulectomy significantly improved pain intensity during intercourse from baseline to 6-mo follow-up compared with GCBT and EMG biofeedback (P <0.01). Pain (MPQ PRI 0-78) significantly reduced in all treatment groups (P < .01). Vestibulectomy reduced pain by 46.8%, GCBT by 27.7%, and biofeedback by 22.8%. Between-group comparison was not reported. 2008: 68% of women participated at 2.5-y follow-up. All groups had a significant reduction in pain at 2.5 y (P < .01). Vestibulectomy group had significantly lower cotton swab test vulvar pain from 6 mo to 2.5 y as compared with biofeedback F(62,75) = 8.96 (P < .01), and GCBT F(2,75) = 10.38 (P < .01). Vestibulectomy group had significantly lower pain during intercourse than the biofeedback group F(2,75) = 3.50 (P < .05) but was not compared with the GCBT group. Vestibulectomy group pain (MPQ PRI) was significantly lower than biofeedback (P < .05) and GCBT groups (P < .05). |

| Cold knife posterior vulvectomy |

2011 N = 57 Vulvar vestibulitis |

2c |

Prospective descriptive cohort study Cold knife posterior vulvectomies performed from 1995 to 2007 Long-term follow-up performed for a median of 36 mo (range 5 to 158 mo) No set time points for data collection |

19 (35.2%) of participants reported they were cured by vulvectomy (complete response); 30 (55.6%) had partial response, and 5 (9.3%) had no response. Dyspareunia (VAS 0-10) reduced from 9 to 3 (66.7% decrease; P < .001). 7 (13%) women reported dyspareunia that required topical anesthetic postoperatively. Posterior vestibular tenderness measured with the cotton swab test (0-10) was absent in 34 (64.2%) participants, 14 (25.9%) reported some degree of constant vulvar pain, and 21% had complications (bleeding, hematoma, infection, Bartholin's cyst, vulvar fissure). Duration of wound pain was 14 d (range = 0-90 d). Duration of sick leave for postoperative recovery was 10.5 d (range 3-24 d). |

|

Yag laser Multidisciplinary Treatment |

Trutnovsky et al79 2021 N = 67 Vulvodynia |

1c |

Case study 2 arms: (1) Yag laser up to 3 sessions with 1 session per mo along with a multidisciplinary treatment program (n = 35) (2) Interprofessional treatment program that did not include Yag laser (n = 32) |

Yag laser significantly reduced mean (SD) pain during a vulvar cotton swab test (NRS 0-10) from 6.1 (2.6) to 3.1 (2.6) 1-mo posttreatment (P < .001). At 9-12 mo Yag laser group participants reported 26% were a lot better, 17% better, 23% a little better and 34% unchanged. Multidisciplinary group reported 13% a lot better, 41% better, 28% a little better, and 19% unchanged. At 9-12 mo there was 73% overall improvement with no significant difference between groups (P = .6). |

| Fractional CO2 laser |

Murina et al80 2016 N = 70 Vestibulodynia, n = 37 Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, n = 33 |

4 |

Case series Women underwent 3 fractional CO2 laser treatments Data collected at baseline, 4, 8, 12 wk, and 4 mo |

Using analysis of covariance, there was a statistically significant difference in vulvar pain scores (VAS 0-10) in both groups (P < .05) through 4-mo follow-up. No statistical results reported, only discussion of results. 13 (35.2%) of the vestibulodynia group reported dyspareunia (Marinoff dyspareunia scale 0-3) symptoms were very improved, 12 (32.4%) reported symptoms improved, and 12 (32.4%) reported no change in dyspareunia. |

| Arthroscopic surgery |

Coady et al13 2015 N = 26 Femoral acetabular impingement syndrome and generalized vulvodynia or clitorodynia |

4 |

Case series Uncontrolled observational Arthroscopic surgery to remove impingement between acetabular rim and femoral head |

Vulvar pain (NRS 0-10) was reduced from 6.7 to 3 postoperatively in the improvement group. Pain was reduced from 6.7 to 4.8 postoperatively in the non-improvement group. There was a significant reduction in pain between groups (P = .03). Only 6 (23%) had significant reduction in pain after arthroscopy, and they were all under 30 y old. 1 woman had worse pain. |

- Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; GCBT, group cognitive behavioral therapy; MPQ PRI, McGill Pain Questionnaire Pain Rating Index; NRS, numeric ratings scale; VAS, visual analog scale

KTP-Nd Yag laser uses a deep depth of ablation, may assist in remodeling collagen and vasculature, and may destroy pain fibers. There was a non-randomized case series79 of 67 women who were self-selected to receive an interprofessional treatment program including up to 3 Yag laser treatments (35 women) at least one month apart compared with 32 women receiving usual care for vulvodynia without laser therapy. Baseline differences were not controlled. There was a significant reduction in pain at one-month follow-up in women receiving laser therapy, but no difference in pain at 9-to-12–month follow-up. There was a second case series80 using fractional CO2 laser (used for skin resurfacing at a superficial level) for PV; 67.6% of women with PV reported improvement, and all patients completed the therapy. Efficacy of both KTP-Nd Yag laser and CO2 laser need to be tested in RCTs.

Arthroscopic Hip Surgery

Orthopedists, physiatrists, and physical therapists have observed a relationship between generalized vulvodynia and intra-articular hip disorders, such as femoro-acetabular impingement syndrome and labral tears (Table 8). The labrum is the connective tissue lining of the acetabulum (the hip socket) where the head of the femur inserts and aids in smooth movement and increases stability of the hip joint.13, 81 In a case series13 of 26 individuals with femoro-acetabular impingement syndrome and vulvodynia, arthroscopic correction improved vulvar pain postoperatively in 6 (23%) women under the age of 30. Clinicians may consider an orthopedic source of vulvar pain and referral to an orthopedist and/or physical therapist as warranted.

Cannabis

Medical cannabis has been used to treat chronic neuropathic pain conditions (Table 9).82 Cannabis has anti-inflammatory properties.83 Medical cannabis is not legal in all states and remains illegal at the federal level. Therefore there are few federal funding mechanisms supporting studies on the pain-relieving properties of cannabis.84 An online survey of 38 women with vulvodynia found that cannabis reduced vulvar pain and dyspareunia; however, the route of administration was not reported.85 There have been no rigorous studies on the use of medical cannabis, including utility and safety profiles, for vulvodynia.

| Treatment |

Author/ Year/ Sample Size |

Level of Evidence | Study Design/Treatment Groups/Dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis |

Barach et al85 2020 N = 38 Vulvodynia |

2c |

Online survey Pain relief of vulvodynia symptoms from cannabis use. Average use 17.3 d/mo Route of consumption not stated |

Using cannabis significantly improved sharp/stabbing, dyspareunia, soreness, burning, stinging, throbbing, rawness, itching, and pain with sitting, exercise, and tight pants (Likert −2 to 2) (P = .002) as well as tampon insertion pain (P < .001) using two-tailed t-test. |

DISCUSSION

Vulvodynia research is in its infancy. Most studies lack control groups, have small sample sizes, and do not compare multiple treatment groups with one another. These design flaws limit validity, rigor, reproducibility, and generalizability, which makes it difficult for clinicians to prescribe therapies for vulvodynia that are evidence-based. Also, measures of pain and dyspareunia are not standardized between studies, making it difficult to compare study results.86 There is little evidence supporting the efficacy of treatments for vulvodynia, singularly or together. Most vulvodynia studies were performed in a clinical setting with women expecting treatment and not expecting to be randomized to a non-treatment or placebo control group.2 It is unknown what the effect of a control group would have had on study treatment outcomes for vulvar pain and dyspareunia. For example, several RCTs21, 46, 47 found no reduction in dyspareunia compared with placebo controls. Placebo treatments can have a therapeutic effect of up to 58%.87 Without a control group it cannot be determined if findings are due to the treatment or other influencing factors. Placebo groups allow for the true treatment effect to be determined. Also, in studies testing multiple treatments, the benefit of using multiple modalities compared with individual treatments has not been tested.2

Recommended Treatments for Vulvodynia

There is uncertainty as to how to afford relief to women who suffer from the debilitating pain of vulvodynia. Clinicians tend to prescribe empirically, based on treatments that have worked for women or recommendations from colleagues. The authors recommend that once women are diagnosed with vulvodynia, clinicians teach women to evaluate their vulvar pain and dyspareunia on a 0 to 10 NRS, keeping a log of their pain ratings and treatments attempted. Tracking this information will enable the clinician and woman to develop a personalized treatment plan.

Once diagnosed, women can be referred to the National Vulvodynia Association (nva.org), which has resources and listings for local support groups, as well as a quarterly newsletter summarizing the latest research. The National Vulvodynia Association also has clinician resources. There are also support groups on social media, including Facebook and Reddit.

Changes in sexual position, vaginal lubricants, and good hygiene will not reduce the pain of vulvodynia. Suggestions that women need “to just relax” during intercourse or get more “turned on” in response to reports of dyspareunia are patronizing, dismissive, and not therapeutic. It is the authors’ opinion that these comments may be offered by the clinician because women may not respond to treatments and clinicians may feel helpless.

There are 8 treatments that have the highest level of evidence for reduction of pain and/or dyspareunia based on either RCTs or a comparative effectiveness trial. The authors recommend clinicians first prescribe these 8 treatments. Therapies that are non-pharmacologic and least or minimally invasive can be attempted first with additional treatments as needed: (1) multimodal physical therapy (education, pelvic floor muscle exercises with biofeedback, manual therapy, and vaginal dilators),22 (2) acupuncture,64 (3) intravaginal TENS (as a single therapy),60 (4) overnight 5% lidocaine ointment soaked in a gauze and applied to the vulvar vestibule,22 (5) oral desipramine with 5% lidocaine cream,21 (6) intravaginal diazepam tablets with intravaginal TENS,48 (7) botulinum toxin type A 50 units,67 and (8) enoxaparin sodium (low-molecular-weight heparin) subcutaneous injection.70

The following non-pharmacologic treatments have shown reduction in pain and/or dyspareunia in pre to posttest studies or group comparisons without a control group. This group includes vaginal dilators (as a single therapy),55 EMG biofeedback,56-58 hypnotherapy,76 and CBT.26, 56, 57, 72-75

If further treatment is warranted, there is low-quality evidence for the following topical treatments that were shown to reduce pain in pre to posttest studies (without a control group): gabapentin cream,28 amitriptyline cream,30 amitriptyline with baclofen cream,29 ketamine-amitriptyline cream,31 conjugated equine estrogen cream,33 and estradiol/testosterone cream.32

There is also low-quality evidence for the use of oral milnacipran (reduced pain pre to posttest studies without a control group)50 and laser therapy (reduced pain in a case series).79, 80 Because of the invasive nature of cold knife vestibulectomy,56, 57, 78 it should be used after other treatment options have been exhausted. See Table 10 for a quick guide to treatment recommendations.

| Line | Treatment Recommendation |

|---|---|

| First line: RCT or comparative effectiveness | |

| Non-pharmacologic | Multimodal physical therapy22 |

| Acupuncture64 | |

| Intravaginal TENS as a single therapy60 | |

| Pharmacologic | Overnight 5% lidocaine cream applied with gauze to vulvar vestibule22 |

| Oral desipramine with 5% lidocaine cream21 | |

| Intravaginal diazepam tablets with intravaginal TENS48 | |

| Invasive pharmacologic | Botulin toxin type A 50 units67 |

| Enoxaparin sodium (low-molecular-weight heparin) subcutaneous injections70 | |

| Second line: Non-pharmacologic; pre to posttest or group comparison without a control group | Vaginal dilators as a single therapy55 |

| EMG biofeedback56-58 | |

| Hypnotherapy76 | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy26, 56, 57, 72-75 | |

| Third line: Topical pharmacologic; pre to posttest without a control group | Gabapentin cream28 |

| Amitriptyline cream30 | |

| Amitriptyline with baclofen cream29 | |

| Ketamine-amitriptyline cream31 | |

| Conjugated equine estrogen cream33 | |

| Estradiol/testosterone cream32 | |

| Fourth line: Case studies or prospective descriptive studies or invasive | Milnacipran50 |

| Laser therapy79, 80 | |

| Cold knife vestibulectomy56, 57, 78 |

- Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 1a | Systematic review of randomized controlled trials |

| 1b | Randomized controlled trials |

| 1c | Case series |

| 2a | Systematic review of cohort studies |

| 2b | Cohort study or subpar randomized controlled trials |

| 2c | Ecological or outcomes research |

| 3a | Systematic review of case control studies |

| 3b | Case control study |

| 4 | Case series and subpar cohort or case control studies |

- Adapted from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (2009).17

Treatments That Have No Support for Use in Vulvodynia

Cromolyn sodium, a mast cell stabilizer, reduces chronic urticaria, inflammation, and hypersensitivity reactions. A small-sample double-blind study in women with PV showed that cromolyn sodium cream did not reduce vulvar pain compared with placebo.34 There is no evidence to support prescribing cromolyn sodium for vulvodynia. Nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker, relaxes smooth muscles, decreases inflammatory infiltrates, and reduces hypertonicity of the internal anal sphincter in patients with chronic anal fissures.88 In a double-blind RCT,35 nifedipine showed no reduction in dyspareunia in women with PV as compared with placebo. Antiepileptics treat vulvodynia by calming the central nervous system and are used to treat neuropathic pain conditions.89, 90 In a multicenter double-blind crossover RCT, oral gabapentin did not reduce dyspareunia.90 There is no evidence to support the use of oral gabapentin for vulvodynia.

Future of Vulvodynia Treatments

Because the etiology of vulvodynia remains unknown, it has been virtually impossible to develop effective treatments for the 7% of American women suffering from vulvodynia. Vulvodynia treatments are still based largely on case and anecdotal reports. As of late, vulvodynia specialists are beginning to focus more on uncovering the etiologic factors of vulvodynia and their potential associations that may guide future vulvodynia treatments. This scientific progress is reflected in emerging new diagnostic subcategories of vulvodynia based on etiology.91 These diagnostic subcategories have not been validated. Most are based on either histological findings from vulvar biopsy or response to expensive or invasive testing such as 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging and serial pudendal nerve blocks. Currently, expert clinicians have started to use these diagnostic subcategories to guide their management of women with vulvodynia.91 These subcategories may be subject to change and are based on specific clinical findings. They are (1) hormonally associated vestibulodynia, (2) inflammatory vestibulodynia, (3) congenital neuroproliferative vestibulodynia, (4) acquired neuroproliferative vestibulodynia, and (5) overactive (hypertonic) pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Other factors associated with vulvodynia that have been identified include (1) pudendal neuralgia, (2) spinal pathology and vulvar dysesthesia, and (3) persistent genital arousal disorder. There are no plans at this time to issue a new set of definitions and guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of vulvodynia. An NIH-sponsored study, “Vestibulodynia: Understanding Pathophysiology and Determining Appropriate Treatments (VBD UPDATe),” is currently underway.92 The investigators have identified 2 distinct subtypes of vestibulodynia that may benefit from 2 distinct types of treatments. The subtypes differ based on patient-reported outcomes, physical and mental health, production of cytokines involved with inflammation, and expression of microRNAs that regulate gene expression. The study is in its third of 5 years.

CONCLUSION

It is remarkable how many treatments, including vestibulectomy, women are willing to undergo to obtain relief from the symptoms of vulvodynia.18 Because current treatments for vulvodynia only focus on symptom amelioration, there is a need for research that focuses on the etiology and characterization of vulvodynia. This article provides a framework for clinicians to understand, diagnose, and treat women with vulvodynia using evidence-based approaches. The authors encourage clinicians to avail themselves of changes in the state of the science when treating women with vulvodynia. Importantly, there is an urgent need to conduct rigorous controlled trials to identify the most effective treatments for this difficult condition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was made possible in part by grants R01 HD091210 and R01 HD089935 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Eunice Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, grant R01 HL133590, and NIH National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR), grants F31 NR019529 and F31 NR019716. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD, NHLBI, or NINR. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy. This publication is co-sponsored by the Rockefeller University Heilbrunn Family Center for Research Nursing through the generosity of the Heilbrunn Family and the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through Rockefeller University, grant UL1 TR001866.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.