Non-pharmacological interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities and depression: a systematic review

Abstract

Background

Although high rates of depression symptoms are reported in adults with intellectual disabilities (IDs), there is a lack of knowledge about non-pharmacological treatment options for depression in this population. The first research question of this paper is: Which non-pharmacological interventions have been studied in adults with ID and depression? The second research question is: What were the results of these non-pharmacological interventions?

Method

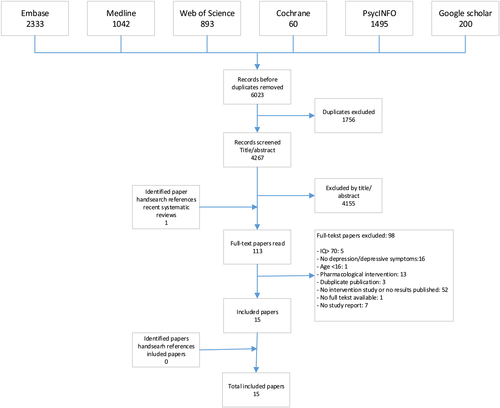

Systematic review of the literature with an electronic search in six databases has been completed with hand searches. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines have been followed. Selected studies met predefined inclusion criteria.

Results

Literature search resulted in 4267 papers of which 15 met the inclusion criteria. Five different types of non-pharmacological interventions have been studied: cognitive behavioural therapy, behavioural therapy, exercise intervention, social problem-solving skills programme and bright light therapy.

Conclusion

There are only a few studies of good quality evaluating non-pharmacological interventions for adults with ID and depression. Some of these studies, especially studies on cognitive behavioural therapy, show good results in decreasing depressive symptoms. High-quality randomised controlled trials evaluating non-pharmacological interventions with follow-up are needed.

Background

Since the 1980s, there is awareness that psychiatric disorders can co-occur with intellectual disabilities (IDs) (Sovner & Hurley 1983; Marston et al. 1997; Cooper et al. 2007; Hurley 2008; Hermans et al. 2013). Nowadays, we know that depression is a common psychiatric disorder in adults with ID. The prevalence range of depression in the ID population varies from 2.2% to 7.6% (Deb et al. 2001; Smiley 2005; Cooper et al. 2007; Hermans et al. 2013). The prevalence is higher compared with that in the general population, despite the fact that depressive symptoms can be difficult to recognise in this population (Marston et al. 1997; Hurley 2008; Hermans et al. 2013). Depression is mainly characterised by sadness and loss of interest or pleasure (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Depression has a major impact on the quality of life (QoL) and leads to cognitive, social and physical problems (Coryell et al. 1993; Hays et al. 1995; Bijl & Ravelli 2000; Sprangers et al. 2000; Beekman et al. 2002; Alonso et al. 2004; Judd et al. 2008; Kober 2010; Horovitz et al. 2014; Rand & Malley 2017). Horovitz et al. (2014) found a significantly higher QoL in a group of adults with ID without Axis I diagnosis compared with adults with ID in the anxiety/mood disorder diagnosis group. Furthermore, adults with ID with higher levels of anxiety/depression are more likely to report a poor QoL (Rand & Malley 2017).

In the general population, antidepressants are frequently prescribed to treat depressive symptoms. Psychoactive medications, including antidepressants, are regularly prescribed in adults with ID, primarily to reduce challenging behaviour (Lott et al. 2004; Deb et al. 2009; Matson & Mahan 2010; Sheehan et al. 2015). There is some evidence that antidepressant medication can decrease depressive symptoms in adults with ID (Masi et al. 1997; Verhoeven et al. 2001; Janowsky et al. 2005). For example, in a group of 20 participants, Verhoeven et al. (2001) found Citalopram effective in decreasing depressive symptoms. Many adults with ID use more than one medication, and polypharmacy is common in adults with ID (Haider et al. 2014; Häβler et al. 2015; Bowring et al. 2017). Negative side effects (short term and long term) can appear when psychoactive medications are used in adults with ID (Deb et al. 2009; Mahan et al. 2010; Matson & Mahan 2010; Eady et al. 2015; Häβler et al. 2015). For example, physical complaints, neurological damage, movement side effects and physiological problems are mentioned (de Leon et al. 2009; Matson & Mahan 2010; Sheehan et al. 2017). Besides, adults with ID seem to be more amenable to develop side effects compared with the general population when psychoactive medications are used (Arnold 1993; Matson & Mahan 2010; Sheehan et al. 2017). Moreover, it can take a while for a psychoactive medication to work in the right daily dosage, and adults with ID may experience even more side effects when more than one psychotropic medication is used (Matson & Mahan 2010). Therefore, there is a need for evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments for depression in adults with ID.

In the general population, a wide range of systematic reviews on non-pharmacological interventions for depression have been published over the last couple of years (Merry et al. 2011; Cox et al. 2012; Catalan-Matamoros et al. 2016; Kvam et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2016; Stubbs et al. 2016). Unfortunately, the conclusions of these reviews (both positive and negative) cannot be generalised to the ID population because a large part of the non-pharmacological interventions for depression of the general population are not suitable for adults with ID. Next to cognitive limitations, adults with ID frequently have verbal limitations. Psychological interventions, for example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), are too difficult for adults with a more severe ID and for those with verbal limitations. Furthermore, a large part of people with ID have physical limitations as well (Cooper et al. 2015). Consequently, exercise interventions can be too complicated to perform or physically impossible.

A few systematic reviews concerning non-pharmacological interventions for depression for adults with ID have been published. Some studies are investigating interventions for a part of the ID population. For example, Osugo & Cooper (2016) focused on interventions for adults with mild ID and mental ill health. They concluded that there was some evidence for group CBT (although larger trials are needed) but that in general the evidence-based interventions for people with mild ID and mental problems were limited. Koslowski et al. (2016) investigated in their systematic review and meta-analyses the effectiveness of interventions on mental health problems in adults with mild to moderate ID. They found no strong evidence for interventions aimed at improving mental health problems, including depression, and found a non-significant moderate effect size [d = 0.49, 95% confidence interval (CI)-0.05 to 1.03; P = 0.08] for depression interventions (psychotherapy only). The focus of other reviews in this research area is on specific treatments only. For instance, Vereenooghe & Langdon (2013) did a meta-analysis on psychological therapies for people with ID and mental health problems and found an overall moderate between-group effect size (g = 0.682, 95% CI 0.379 to 0.985). Furthermore, a subgroup meta-analysis indicated that individually psychological therapy (g = 0.778, 95% CI 0.110 to 1.445) was more effective than group-based psychological therapy (g = 0.558, 95% CI 0.212 to 0.903) and psychological interventions for depression had a moderate effect size (g = 0.742, 95% CI −0.116 to 1.599).

Depression can occur in all levels of ID. Hence, an overview of evidence-based non-pharmacological interventions for depression for the whole ID population is needed, as the severe and profound ID population got no or little attention in previous reviews. Therefore, the aim of this review is to evaluate non-pharmacological treatments for adults with ID (all levels) and depression. Our first research question is: Which non-pharmacological interventions have been studied in adults with ID and depression? Our second research question is: What were the results of these non-pharmacological interventions?

Method

We have used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses checklist to perform this study (Moher et al. 2009). The study is registered in the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO 2016: CRD42016051524).

Data sources

An electronic search in six databases, Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane, PsycINFO and Google Scholar, has been performed on 3 October 2016. The search strategy (for the databases mentioned previously) is included in Appendix 1. The electronic search has been completed with hand searches in reference lists of recent systematic reviews (published between January 2012 and 3 October 2016) and in reference lists of included papers.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria have been clearly defined before the start of the study. All papers published in English before 3 October 2016, mentioning non-pharmacological interventions for treating depression (of any type) or depressive symptoms in adults (aged ≥16 years) with ID (IQ ≤ 70), have been selected. Outcome measures on depressive symptoms must be mentioned in the paper to be included. Because the aim of this study is to find all non-pharmacological interventions for adults with ID and depression, no exclusion on type of study design has been made. Therefore, all different kinds of study designs, from case study to randomised controlled trial (RCT), were included. The choice to include all study designs contributes to the presentation of the current state of evidence for the different types of non-pharmacological interventions, and possible gaps of knowledge can be exposed.

When a combined population of children and adults was described in a paper, the results of the adult population must be separately presented to be included. The same applies to level of ID: when the study population also contained adults with an IQ of more than 70, the population with IQ ≤ 70 must be separately presented to be included. In some papers, combined interventions (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) are described. Papers are only included when the results of both of these interventions are studied separately. (Systematic) reviews of non-pharmacological interventions, as well as narrative papers without results and congress abstracts, were not included in the current review.

Process of the study selection

After identifying papers through the electronic search, duplicates have been removed. Then, title and abstract of the papers have been scanned by two reviewers (PH and HH) independently, according to the predefined inclusion criteria mentioned previously. After the selection of all relevant records on title and abstract, the databases of the two reviewers were merged to see if there was any disagreement about included papers. Any disagreement was solved by discussion in a consensus meeting. Reference lists of recent systematic reviews were studied by both reviewers (PH and HH) for relevant studies. Hereafter, full texts of all remaining papers have been assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (PH and HH) independently. Hand searches in reference lists of included papers were done to search for relevant papers to include. The potential relevant papers of both hand searches were discussed by both reviewers (PH and HH) before including the papers in the final database. After this step, the final database was created. See Fig. 1 for the flow chart of the selection of studies. Data extraction of the included studies has been performed by one reviewer (PH) and checked by the second reviewer (HH). See Tables 1a and 1b for details of the study characteristics.

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size |

Participants (age, gender and level of ID) |

Intervention | Measured depression outcome | Results on depressive symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCabe et al. (2006) | RCT |

n = 34: 19 EG, 15 CG. (The CG group later also took part of the EG). Total EG: 34 |

Mean age: 34.1 (EG), 39.8 (CG) | Group CBT, 5 weeks, 2 h sessions. Control group: waiting list. | BDI-II, ATQ-R | Intervention significantly decreased depressive symptoms and negative automatic thoughts. |

| 22 M (16 EG + 6 CG)/27 F (18 EG + 9 CG) | Follow-up (3 months, n = 18): impact of the intervention on depressive symptoms sustained over time; no further improvement found. | |||||

| Mild–moderate ID | ||||||

| McGillivray et al. (2008) | RCT |

n = 47: 20 TG, 27 CG. Control group received treatment as well after follow-up (TG 2). |

Mean age: 38.4 (TG), 31.2 (CG) | Staff administered group CBT programme, 12 weeks, 2 h sessions. | BDI-II, ATQ-R | Significant decrease in depressive symptoms and negative automatic thoughts in the CBT group. |

| Follow-up (3 months): positive effects maintained. | ||||||

| 32 M (TG 13, CG 19)/15 F (TG 7, CG 8) | ||||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| Ghafoori et al. (2010) | Pilot study, one group (pre, post and follow-up) | n = 8 | Mean age: 20.0 | Cognitive behavioural group therapy programme, 9 weeks, 1.5 h sessions. | SCL-90-R | Significant improvements in six primary dimensions of the SCL-90-R, including ‘depression’. |

| 2 M/6 F | ||||||

| Follow-up (4 months): no significant treatment effects maintained at follow-up. | ||||||

| Mild–moderate ID | ||||||

| Hassiotis et al. (2013) | RCT | n = 32: 16 TG, 16 CG. | Mean age: 33.7 (M-iCBT), 38.3 (TAU) | M-iCBT, 16 weeks, 1 h sessions. Control: treatment as usual. | BDI-Y | No significant treatment effect. |

| Follow-up (6 months): no significant effects on depression. | ||||||

| 12 M/20 F | ||||||

| Mild–moderate ID | ||||||

| McGillivray & Kershaw (2013) | Controlled trial (pre, post and follow-up) | n = 82: 32 G1, 24 G2, 26 G3. | Mean age overall = 37* | Staff administered group CBT programme with (1) a staff-initiated referral to a GP, (2) staff administered group CBT programme only, (3) referral to GP only. | BDI-II, ATQ-R | CB-only group and CB with GP referral group: greatest reduction in depression symptoms directly after the programme. Significant reduction in frequency of negative automatic only in the CB-only group. |

| 47 M/35 F* | ||||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| Follow-up (8 months): CB strategies (particularly CB with referral to GP) appeared effective in reducing depressive symptoms and negative automatic thoughts. | ||||||

| McGillivray & Kershaw (2015) | Controlled trial (pre, post and follow-up) | n = 70: 23 G1, 23 G2, 24 G3. | Mean age overall: 36.0* | Cognitive and behavioural strategies (group 1), cognitive focused strategies (group 2), behavioural focused strategies (group 3). | BDI-II, ATQ-R. | The mean depression scores decreased in all three intervention groups after the intervention. No significant difference between groups. |

| 42 M/28 F* | ||||||

| Mild ID | Follow-up (6 months): group 1, all individuals indicated improvement; group 2, 67% maintained improvement; group 3, 47% maintained improvement. | |||||

| Lindsay et al. (2015) | Controlled trial (pre, post and follow-up) | n = 24: 12 TG, 12 CG | Mean age: 28.9 (TG), 33.1 (CG) | Experimental group: individual CBT. | BSI, GDS | No significant effect on BSI depression score. Statistically significant reductions in self-reported depression (GDS) and carer-reported depression (GDS). |

| Control group: waitlist (TAU). | ||||||

| 12 M (6 TG + 6 CG)/12 F (6 TG + 6 CG) | ||||||

| Follow-up (3 to 6 months follow-up; treatment group only): significant decrease on the GDS maintained. | ||||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| Jahoda et al. (2015) | Feasibility study (one group: pre, post and follow-up) | n = 21 | Mean age = 42.2 | Behavioural activation, 10–12 sessions. | GDS-LD# | Significant reduction in self-report depressive symptoms. Positive change for informant reports on depressive symptoms. |

| 12 M/9 F | IDDS# | |||||

| Mild–moderate–severe ID | ||||||

| Follow-up (3 months): reduction depressive symptoms maintained. | ||||||

| Heller et al. (2004) | RCT | n = 53: 32 TG, 21 CG | Mean age: 39.41 (TG), 40.22 (CG) |

TG: 12 weeks, 3 days per week health promotion programme, 2 h a day (1 h exercise + 1 h health education). CG: no training. |

CDI | Participants in the intervention group were less depressed than those in the control group (marginally significant). |

| 24 M/29 F | No follow-up. | |||||

| Mild–moderate ID | ||||||

| Carraro & Gobbi (2014) | RCT | n = 27: 14 EG, 13 CG | Mean age overall: 40.1* | Short-term group-based exercise programme, 12 weeks, two times a week, 1 h sessions. | Zung Self-rating Depression Scale | Significant reduction of depressive symptoms in the exercise group compared with the control group. |

| 16 M/11 F* | Control group: painting activities. | No follow-up. | ||||

| Mild–moderate ID |

- * Not specified per group.

- # Measurements especially developed for people with ID.

- ATQ-R, Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire–Revised; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-Y, Beck Depression Inventory Youth; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; CDI, Children's Depression Inventory; F, female; GDS-LD, Glasgow Depression Scale for people with learning disabilities; ID, intellectual disability; IDDS, Intellectual Disabilities Depression Scale; M, male; M-iCBT, manualised individual cognitive behavioural therapy; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist-90–Revised; TAU, treatment as usual.

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size |

Participants (age, gender and level of ID) |

Intervention | Measured depression outcome | Results on depressive symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindsay et al. (1993) | Case studies | n = 2 | Mean age: 24 | Cognitive therapy (duration/frequency of therapy is unclear). | Zung Depression Scale | Both subjects improved on the Zung Depression Scale. Suicidal thoughts decreased in one participant. |

| 1 M/1 F | ||||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| Follow-up (6 weeks): reductions on depression scores maintained. | ||||||

| Matson (1982) | Case studies | n = 4 | Mean age: 33.5 | Behavioural therapy, 10–35 sessions. |

Self-rating Depression Scale BDI |

Significant decrease of depressive symptoms on both scales. |

| 3 F/1 M | Follow-up (4–6 months): treatment effect maintained. | |||||

| Mild–moderate ID | ||||||

| Stuart et al. (2014) | Case study | n = 1 | Age: 40.0 | Seven sessions of therapy over 3 months (simplified behavioural activation and daily audio-bases progressive muscular relaxation). | GDS-LD# | Decrease in depressive symptoms on the GDS-LD but still above the cut-off point. |

| 1 F | ||||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| No follow-up. | ||||||

| Anderson & Kazantzis (2008) | Case studies | n = 3 | Age range: 19–52 (no mean published) | Social problem-solving skills training, 15 individual sessions. | Adapted Zung Depression Scale# | Pretreatment—follow-up: depression showed a 40% change in one case and 31% change in another case. |

| 2 M/1 F | Follow-up (4 weeks): improvement maintained. | |||||

| Mild ID | ||||||

| Altabet et al. (2002) | Case studies | n = 3 | Mean age: 57 | LT sessions, 30 min (between 08:00 and 10:00 h), 10.000 lux, 5 days per week for 12 weeks. | DASH# (depression sub-scale) | Positive effects on mood and sleep patterns. |

| Follow-up (3 weeks): treatment gains maintained; (8 weeks): increased depressive symptoms. | ||||||

| 1 M/2 F | ABC# (lethargy and irritability sub-scale) | |||||

| Profound ID | ||||||

| Mood chart |

- # Measurements especially developed for people with ID.

- ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DASH, Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped; F, female; GDS-LD, Glasgow Depression Scale for people with learning disabilities; ID, intellectual disability; LT, light therapy; M, male.

Quality assessment of the included studies

To evaluate the quality of the included studies, the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins & Green 2011) has been used by two reviewers independently (PH and HH), and any disagreement has been discussed in a second consensus meeting. With this tool, six domains were assessed to evaluate the quality of the included studies: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and possible other bias. Low risk of a specific bias is rated with a ‘+’. For example, there is a low risk of performance bias when participants and researchers do not know which intervention the participant will receive (blinding). When there is a high risk of a specific bias, that bias is marked with a ‘−’. For example, when there is a high risk of selection bias because of inadequate concealment of allocations, a question mark is used when not enough information is given in the paper to make a clear judgement. The included studies have also been screened for mentioning conflicts of interest.

Quality assessment of the current systematic review

AMSTAR (which stands for A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) is used by an independent researcher to assess the methodological quality of the current review (Shea et al. 2007). The goals of the AMSTAR include creating valid, reliable and useable instruments to differentiate between systematic reviews. Besides, the AMSTAR facilitates the development of high-quality reviews. The AMSTAR checklist consists of 11 questions and seems to be a valid and reliable instrument (Shea et al. 2009).

Results

The electronic search identified 6023 papers. After removing duplications, 4267 papers have been included in the initial database. These 4267 papers have been screened on title and abstract by two reviewers independently (PH and HH). The reference lists of recent systematic reviews (Flynn 2012; Sturmey 2012; Chen 2013; Hwang & Kearney 2013; Matson 2013; Vereenooghe & Langdon 2013; Jennings & Hewitt 2015; Koslowski et al. 2016; Maber-Aleksandrowicz et al. 2016; Osugo & Cooper 2016; Unwin et al. 2016) were studied for relevant papers by these two reviewers as well. One relevant new paper was found. Both reviewers read 113 full-text articles and screened these papers on the inclusion criteria. The main exclusion reason was the absence of study results (e.g. narrative articles or study results on depressive symptoms were not published) (Fig. 1). A total of 15 papers have been included after full-text screening. Hand searches in reference lists of these included papers (also done by reviewers PH and HH) did not reveal other relevant papers to include in the final database. Therefore, the final database contained 15 papers.

Description of the included studies

Five different types of non-pharmacological interventions are identified in the included studies of this review: CBT, behavioural therapy, exercise intervention, social problem-solving skills programme and bright light therapy (BLT). Some of these interventions are developed for the ID population; others are adjusted versions of interventions of the general population. The interventions will be discussed in the succeeding sections, and the characteristics of the studies are presented in Tables 1a and 1b.

Quality assessment of the included studies

According to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, none of the included papers had a low risk of bias on all domains and much is unclear because of a lack of reporting. Two studies scored a low risk of bias on five out of seven criteria (Hassiotis et al. 2013; Carraro & Gobbi 2014). Only one study mentioned no conflicts of interest (Hassiotis et al. 2013). In the other papers, nothing was mentioned about any conflicts on this matter. In Table 2, the details of the quality assessment are shown.

| Selection bias (random sequence generation) | Selection bias (allocation concealment) | Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) | Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment) | Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) | Reporting bias (selective reporting) | Other sources of bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matson (1982) | − | − | − | − | + | ? | − |

| Lindsay et al. (1993) | − | − | − | − | + | ? | − |

| Altabet et al. (2002) | − | − | − | − | + | ? | − |

| Heller et al. (2004) | ? | ? | + | + | + | ? | + |

| McCabe et al. (2006) | ? | ? | + | + | + | ? | − |

| Anderson & Kazantzis (2008) | − | − | − | + | + | ? | ? |

| McGillivray et al. (2008) | ? | ? | + | + | + | ? | − |

| Ghafoori et al. (2010) | ? | ? | − | + | + | ? | − |

| Hassiotis et al. (2013) | ? | + | + | + | + | ? | + |

| McGillivray & Kershaw (2013) | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | ? |

| Carraro & Gobbi (2014) | + | − | + | + | + | ? | + |

| Stuart et al. (2014) | − | − | − | + | + | ? | − |

| Jahoda et al. (2015) | − | − | + | − | + | ? | − |

| McGillivray & Kershaw (2015) | − | − | − | + | + | ? | + |

| Lindsay et al. (2015) | − | − | + | + | + | ? | + |

- ‘+’ = low risk; ‘−’ = high risk; ‘?’ = unclear.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy is the most common studied intervention to decrease depressive symptoms. CBT is a psychotherapy in which thoughts, beliefs and attitudes are discussed. In CBT, thoughts are modified in order to change mood and behaviour. Eight studies focused on CBT (Lindsay et al. 1993; McCabe et al. 2006; McGillivray et al. 2008; Ghafoori et al. 2010; Hassiotis et al. 2013; McGillivray & Kershaw 2013; Lindsay et al. 2015; McGillivray & Kershaw 2015). Three studies were RCTs with follow-up (McCabe et al. 2006; McGillivray et al. 2008; Hassiotis et al. 2013). Three studies were controlled trials with pre, post and follow-up measurements (McGillivray & Kershaw 2013; Lindsay et al. 2015; McGillivray & Kershaw 2015). The study of Ghafoori et al. (2010) was a pilot study with one group with pre, post and follow-up measurements. Two cases were described in the study of Lindsay et al. (1993).

Seven of these studies reported significantly decreased depression symptoms after CBT; one high-quality study (Hassiotis et al. 2013) did not find significant treatment effects. In the study of Lindsay et al. (2015), no significant effect was found in the Brief Symptom Inventory Depression Scale, but they did found significant reductions in self-reported depression and carer-reported depression (Glasgow Depression Scale). In six of the seven studies with positive results, the improvement maintained at follow-up. Based on the results and quality of the included studies, CBT seems to be an effective intervention to decrease depressive symptoms in adults with ID, although there are some conflicting results.

Behavioural therapy

In three studies, the effect of behavioural therapy on depressive symptoms has been investigated (Matson 1982; Stuart et al. 2014; Jahoda et al. 2015). Behavioural therapy is based on the theory that a large part of human behaviour is learnt from the environment. In all three studies, participants with mild ID have been included; Matson (1982) and Jahoda et al. (2015) also included participants with moderate or severe ID. None of these three studies on behavioural therapy used control groups next to the experimental groups. In the feasibility study of Jahoda et al. (2015), 21 participants were included in a one group study with pre, post and follow-up measurements. Matson (1982) and Stuart et al. (2014) reported case studies (respectively n = 4 and n = 1). Depressive symptoms were (significantly) decreased after behavioural therapy in all three studies. The patient in the study of Stuart et al. (2014) still had a depression score above the cut-off point after the intervention. In the studies of Matson (1982) and Jahoda et al. (2015), the reduction of depressive symptoms maintained at follow-up. Because of the small sample sizes and no use of control groups in the aforementioned studies, the results on behavioural therapy on decreasing depressive symptoms in adults with ID must be interpreted with caution.

Exercise intervention

In two RCTs, the effect of exercise on depressive symptoms has been investigated (Heller et al. 2004; Carraro & Gobbi 2014). Participants in the study of Heller et al. (2004) participated in a 12-week (3 days per week, 2 h a day), health promotion programme, which consisted of 1 h exercise and 1 h health education per day. The participants in the study of Carraro & Gobbi (2014) participated in a short-term group-based exercise programme (12 weeks, 2 times a week, 1 h sessions). Both studies contained an intervention group and a control group and reported significant reductions on depressive symptoms in the intervention group. Unfortunately, both studies did not mention any follow-up measurements. Based on these two studies, we can conclude that exercise interventions to decrease depressive symptoms are promising.

Social problem-solving skills programme

The only study that focused on social problem-solving skills was a multiple single-case study with three participants (Anderson & Kazantzis 2008). Participants in this study had mild ID and got 15 individual sessions of social problem-solving skills training where they were trained to solve the problems that they encountered in daily life. No control group has been used in this study. Reduction of depressive symptoms was seen in two out of three participants, in whom improvement maintained at the 4-week follow-up. This study should be seen as a first exploration of the potential of problem-solving skills programmes, because of the poor design of this study.

Bright light therapy

Altabet et al. (2002) published three case studies investigating the effect of BLT on depressive symptoms. The participants had a profound ID and participated in a 12-week, five days a week, BLT programme (no control group). Participants got BLT in the morning with a 10.000 lux light box. Positive effects on mood were found, but beneficial treatment effects were not uniform. At 3-week follow-up, treatment gains maintained. The 8-week follow-up showed increased depressive symptoms. As this study only contains case reports, it should be seen as a first consideration of the use of BLT to decrease depressive symptoms in adults with ID.

Quality assessment of the current systematic review

The current study was evaluated by an independent researcher and scored 8 out of 11 points. According to AMSTAR, the strengths of this review are the use of an a priori design, the duplicate study selection and data extraction and Tables 1a and 1b providing characteristics of the included studies.

Discussion

The current systematic review contains 15 studies evaluating the effect of a total of five different non-pharmacological interventions to decrease depressive symptoms in adults with ID. These five different types of non-pharmacological interventions are similar to those found by Holvast et al. (2017) in the elderly population with depression in primary care. Based on our study, we can conclude that CBT is an effective non-pharmacological intervention to decrease depressive symptoms in adults with mild or moderate ID (McCabe et al. 2006; McGillivray et al. 2008; McGillivray & Kershaw 2013; Lindsay et al. 2015; McGillivray & Kershaw 2015). However, these results must be interpreted with caution because of the methodological problems of some studies as seen in the quality assessment. In the general population, CBT is a widely used effective treatment for depression (Butler et al. 2006). CBT can be used in the mild to moderate ID population to decrease depressive symptoms as well, although more RCTs are needed to establish its usefulness in clinical practice. The main part of the included studies in this paper includes interventions for people with mild or moderate ID. In only two studies, people with severe or profound ID have been included, even though it is known that they can suffer from depression as well (Cooper et al. 2007; Hermans et al. 2013). In general, conducting intervention studies in the ID population is challenging. For instance, ethical dilemmas, specific living conditions of people with ID, dependence on professional staff, a difficult informed consent procedure, the burden of the measurements and challenging behaviour are issues researchers are confronted with when conducting intervention studies in this population (Oliver et al. 2002; Hamers et al. 2017). This might be an explanation why intervention studies with adults with severe ID are even more scarce. In the 1980s, Matson already published about behavioural therapy for adults with ID and depression. Unfortunately, none of the studies on behavioural therapy included in this review used control groups (Matson 1982; Stuart et al. 2014; Jahoda et al. 2015). Therefore, we cannot conclude with certainty that behavioural therapy is responsible for the decrease in depressive symptoms. However, as positive results are published in these papers, it seems promising.

In the two studies (RCTs) investigating exercise as a non-pharmacological treatment to decrease depressive symptoms, intervention groups as well as control groups have been used (Heller et al. 2004; Carraro & Gobbi 2014). Both studies reported positive results in decreasing depressive symptoms. In the study of Heller et al. (2004), participants got health education and exercise, and in the study of Carraro & Gobbi (2014), participants got exercise only, which makes it hard to compare these two exercise studies. Despite this fact, exercise interventions seem promising interventions to decrease depression in adults with ID without psychical limitations and should be further studied.

The study of Anderson & Kazantzis (2008) was the only study in this review focusing on social problem-solving skills programme. Unfortunately, this was a multiple single-case study with only three participants, which makes it hard to draw any conclusions about the effect of this intervention on decreasing depressive symptoms (Anderson & Kazantzis 2008). BLT in adults with profound ID is studied by Altabet et al. 2002. Positive effects were seen on mood, but no conclusions can be drawn because of the small sample size and no control group (Altabet et al. 2002), so more research is needed. The recent published pilot study with promising results of Hermans et al. (2017) is the first step towards more insight into the effect of BLT as a treatment for depression in adults with ID.

A large part of the 15 included studies of this review are case reports or studies with a small sample size. Some of the reviewed studies also have methodological problems, for example, no control group or no follow-up. Despite the fact that a large number of adults with ID suffer from depressive symptoms, limited well-conducted studies are carried out to evaluate the effect of non-pharmacological interventions to decrease depressive symptoms.

The strength of the current systematic review is that the whole study selection (from title/abstract to full text) and the quality assessment are done by two reviewers independently. Another strength of this study is that there was no restriction on publication year, so all relevant studies published before the start of this study are screened. Besides, the study protocol of this systematic review was registered at the start of the study, which makes the current systematic review transparent. The methodological quality of the current study was assessed with the AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al. 2007) by an independent researcher and received an AMSTAR score of 8 (out of 11).

A limitation of the current systematic review is the small number of papers that could be included because of the inclusion criteria. Many studies were excluded because of lack of data on study methods and outcome measures. For example, in several papers, the IQ level of participants was not mentioned. Further, depressive outcome measures were not reported in quite a few papers, for example, in the case series of Tsiouris (2007). Because of the small number of papers included in our review, which are spread over five different kinds of interventions, a meta-analysis on the effect of the non-pharmacological treatments was unfortunately not possible. We did not use the ‘grey literature’ in this systematic review. So papers could have been missed. Third, this review is limited by only including papers published in English. Fourth, the included studies are very different in study design, which makes them hard to compare with each other.

The used tool to evaluate the quality of the studies (the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool) is actually designed for (randomised) controlled trials. As for a more pragmatic approach, we used it to evaluate all the study designs of the included papers. Eventually, the use of this specific tool emphasised the poor quality of most of the studies. It is well known that there is a possibility of publication bias of papers with positive outcomes (Dickersin et al. 1987; Easterbrook et al. 1991; Turner et al. 2008; Luijendijk & Koolman 2012) and therefore, papers with negative outcomes can be missed, which may have influenced the results of the current review.

In conclusion, currently CBT is the most well-studied non-pharmacological intervention for depression in people with ID, which seems to be effective as well in the mild and moderate ID population. Other promising interventions are exercise and possibly behavioural therapy and BLT. Although it is known that performing an RCT in adults with ID (and depression) can be challenging, we emphasise that further research, preferably RCTs, is needed to grow the evidence-base for non-pharmacological interventions for people with ID and depression. In this way, the non-pharmacological treatment options in this population can be expanded, which is especially important for those with severe or profound ID who can often only rely on pharmacological treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Wichor Bramer, information specialist of the Ërasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands, for his advice with the search strategy of our study. We also want to thank the three care provider services (Amarant Group, Abrona and Ipse de Bruggen) (= HA-ID consort), which provide financial support during this study. Drs. Sylvie Beumer assessed the methodological quality of this review with the AMSTAR checklist.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1

Search strategies

Embase.com

(‘depression’/exp OR ‘mental health’/exp OR ‘mental disease’/de OR ‘mental patient’/de OR ‘mood disorder’/de OR ‘major affective disorder’/de OR ‘minor affective disorder’/de OR (depressi* OR bipolar* OR (season* NEAR/3 affecti*) OR dysphori* OR dysthymi* OR melancholi* OR pseudodementi* OR psychopatholog* OR ((mental* OR psychiatr*) NEAR/3 (health* OR disorder* OR disease* OR difficult* OR comorbid* OR co-morbid*)) OR ((mood OR affect*) NEAR/3 disorder*)):ab,ti) AND (‘psychiatric treatment’/de OR ‘electroconvulsive therapy’/exp OR ‘psychotherapy’/exp OR ‘physical medicine’/exp OR ‘exercise’/exp OR ‘chronotherapy’/exp OR ((non NEXT/1 pharmac*) OR nonpharmac* OR psychotherap* OR physiotherap* OR phototherap* OR kinesiotherap* OR kinesitherap* OR exercis* OR dramatherap* OR storytell* OR mindfulness* OR ((psychiatr* OR behav* OR cognit* OR psycho* OR dance OR activit* OR activat* OR running OR movement* OR physical* OR light OR group OR electroconvuls* OR drama OR socioemotion* OR emotion* OR mental*) NEAR/3 (treat* OR therap* OR interven*)) OR psychoeducat* OR ‘therapeutic work’ OR chronotherap* OR CBT):ab,ti) AND (‘intellectual impairment’/de OR ‘mental deficiency’/exp OR ‘developmental disorder’/de OR (((intellectual* OR mental* OR learning) NEXT/1 (impair* OR disab* OR deficien* OR handicap* OR retard*)) OR (developmental* NEXT/1 (disorder* OR disab*)) OR (Down* NEAR/3 syndrome*)):ab,ti) AND [english]/lim NOT (‘juvenile’/exp NOT adult/exp)

MEDLINE Ovid

(exp ‘Depression’/ OR exp ‘Mood Disorders’/ OR ‘mental health’/ OR ‘Mental Disorders’/ OR ‘Mentally Ill Persons’/ OR ‘Bipolar Disorder’/ OR (depressi* OR bipolar* OR (season* ADJ3 affecti*) OR dysphori* OR dysthymi* OR melancholi* OR pseudodementi* OR psychopatholog* OR ((mental* OR psychiatr*) ADJ3 (health* OR disorder* OR disease* OR difficult* OR comorbid* OR co-morbid*)) OR ((mood OR affect*) ADJ3 disorder*)).ab,ti.) AND (‘Psychiatric Somatic Therapies’/ OR exp ‘Convulsive Therapy’/ OR exp ‘Psychotherapy’/ OR ‘Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine’/ OR ‘Psychiatric Rehabilitation’/ OR exp ‘Physical Therapy Modalities’/ OR exp ‘exercise’/ OR ‘chronotherapy’/ OR ((non ADJ pharmac*) OR nonpharmac* OR psychotherap* OR physiotherap* OR phototherap* OR kinesiotherap* OR kinesitherap* OR exercis* OR dramatherap* OR storytell* OR mindfulness* OR ((psychiatr* OR behav* OR cognit* OR psycho* OR dance OR activit* OR activat* OR running OR movement* OR physical* OR light OR group OR electroconvuls* OR drama OR socioemotion* OR emotion* OR mental*) ADJ3 (treat* OR therap* OR interven*)) OR psychoeducat* OR ‘therapeutic work’ OR chronotherap* OR CBT).ab,ti.) AND (exp ‘Intellectual Disability’/ OR ‘Developmental Disabilities’/ OR (((intellectual* OR mental* OR learning) ADJ (impair* OR disab* OR deficien* OR handicap* OR retard*)) OR (developmental* ADJ (disorder* OR disab*)) OR (Down* ADJ3 syndrome*)).ab,ti.) AND english.la. NOT ((exp child/ OR exp infant/ OR Adolescent/) NOT exp adult/)

PsycINFO Ovid

(exp ‘Depression (emotion)’/ OR exp ‘Affective Disorders’/ OR ‘mental health’/ OR ‘Mental Disorders’/ OR ‘Bipolar Disorder’/ OR (depressi* OR bipolar* OR (season* ADJ3 affecti*) OR dysphori* OR dysthymi* OR melancholi* OR pseudodementi* OR psychopatholog* OR ((mental* OR psychiatr*) ADJ3 (health* OR disorder* OR disease* OR difficult* OR comorbid* OR co-morbid*)) OR ((mood OR affect*) ADJ3 disorder*)).ab,ti.) AND (‘Physical Treatment Methods’/ OR exp ‘Phototherapy’/ OR exp ‘Electroconvulsive Shock Therapy’/ OR exp ‘Psychotherapy’/ OR exp ‘Physical Therapy’/ OR exp ‘exercise’/ OR ((non ADJ pharmac*) OR nonpharmac* OR psychotherap* OR physiotherap* OR phototherap* OR kinesiotherap* OR kinesitherap* OR exercis* OR dramatherap* OR storytell* OR mindfulness* OR ((psychiatr* OR behav* OR cognit* OR psycho* OR dance OR activit* OR activat* OR running OR movement* OR physical* OR light OR group OR electroconvuls* OR drama OR socioemotion* OR emotion* OR mental*) ADJ3 (treat* OR therap* OR interven*)) OR psychoeducat* OR ‘therapeutic work’ OR chronotherap* OR CBT).ab,ti.) AND (exp ‘Intellectual Development Disorder’/ OR ‘Developmental Disabilities’/ OR (((intellectual* OR mental* OR learning) ADJ (impair* OR disab* OR deficien* OR handicap* OR retard*)) OR (developmental* ADJ (disorder* OR disab*)) OR (Down* ADJ3 syndrome*)).ab,ti.) AND english.la. NOT ((100.ag. OR 200.ag.) NOT 300.ag.)

Cochrane

((depressi* OR bipolar* OR (season* NEAR/3 affecti*) OR dysphori* OR dysthymi* OR melancholi* OR pseudodementi* OR psychopatholog* OR ((mental* OR psychiatr*) NEAR/3 (health* OR disorder* OR disease* OR difficult* OR comorbid* OR co-morbid*)) OR ((mood OR affect*) NEAR/3 disorder*)):ab,ti) AND (((non NEXT/1 pharmac*) OR nonpharmac* OR psychotherap* OR physiotherap* OR phototherap* OR kinesiotherap* OR kinesitherap* OR exercis* OR dramatherap* OR storytell* OR mindfulness* OR ((psychiatr* OR behav* OR cognit* OR psycho* OR dance OR activit* OR activat* OR running OR movement* OR physical* OR light OR group OR electroconvuls* OR drama OR socioemotion* OR emotion* OR mental*) NEAR/3 (treat* OR therap* OR interven*)) OR psychoeducat* OR ‘therapeutic work’ OR chronotherap* OR CBT):ab,ti) AND ((((intellectual* OR mental* OR learning) NEXT/1 (impair* OR disab* OR deficien* OR handicap* OR retard*)) OR (developmental* NEXT/1 (disorder* OR disab*)) OR (Down* NEAR/3 syndrome*)):ab,ti) NOT ((child* OR infan* OR adolescen*) NOT adult*)

Web of Science

TS = (((depressi* OR bipolar* OR (season* NEAR/2 affecti*) OR dysphori* OR dysthymi* OR melancholi* OR pseudodementi* OR psychopatholog* OR ((mental* OR psychiatr*) NEAR/2 (health* OR disorder* OR disease* OR difficult* OR comorbid* OR co-morbid*)) OR ((mood OR affect*) NEAR/2 disorder*))) AND (((non NEAR/1 pharmac*) OR nonpharmac* OR psychotherap* OR physiotherap* OR phototherap* OR kinesiotherap* OR kinesitherap* OR exercis* OR dramatherap* OR storytell* OR mindfulness* OR ((psychiatr* OR behav* OR cognit* OR psycho* OR dance OR activit* OR activat* OR running OR movement* OR physical* OR light OR group OR electroconvuls* OR drama OR socioemotion* OR emotion* OR mental*) NEAR/2 (treat* OR therap* OR interven*)) OR psychoeducat* OR ‘therapeutic work’ OR chronotherap* OR CBT)) AND ((((intellectual* OR mental* OR learning) NEAR/1 (impair* OR disab* OR deficien* OR handicap* OR retard*)) OR (developmental* NEAR/1 (disorder* OR disab*)) OR (Down* NEAR/2 syndrome*))) NOT ((child* OR infan* OR adolescen*) NOT adult*)) AND LA = (english)

Google Scholar

Depression|depressive ‘non pharmaceutical’|psychotherapy|phototherapy|’psychiatric|behavior|cognitive|light therapy’ ‘intellectual|intellectually|mental|mentally impairment|disabled|disability|deficiency|handicap|retarded|retardeation’.