Managing Discretionary Accruals and Book-Tax Differences in Anticipation of Tax Rate Increases: Evidence from China

Abstract

This paper investigates how firms manage their earnings to trade off various incentives when tax rates increase. We hypothesize and find that firms generally choose to manage their taxable income upward in a book-tax non-conforming manner rather than in a book-tax conforming manner before a tax rate increment, which in turn reduces the detection risk of aggressive financial reporting. These results suggest that firms give more weight to tax incentives and tax audit or regulatory inspection risks than to boosting financial reporting income in tax management. However, when firms have higher book management incentives or lower tunneling incentives (i.e., non-state-owned enterprises), we find that they manage their taxable income and book income upward together (i.e., in a book-tax conforming manner), whereas their counterparts (i.e., state-owned enterprises) do not. Overall, our paper contributes to the literature by demonstrating the interplay of tax, tunneling and financial reporting incentives in influencing tax management strategies. The findings from our paper should also help government and regulators understand more about firms’ reactions to tax rate increases.

1 Introduction

This paper examines whether and how firms manage income in response to tax rate increases. Prior research demonstrates that an anticipated tax rate reduction provides incentives for firms to manage taxab1e income and book income downward simultaneously (Guenther, 1994; Lopez et al., 1998; Roubi and Richardson, 1998; Adhikari et al., 2005; Lin, 2006). We note, however, that there is a scarcity of studies that examine whether and how firms manage (book and/or taxable) earnings in anticipation to tax rate increases. Under International Accounting Standards (IAS 12), effective tax planning includes creating or increasing taxable profits in an appropriate period (e.g., in the period before expiry of a tax loss or a tax credit carryforward, or in the period before a tax rate increase) such that the overall tax liabilities (i.e., the net present value of tax payments)1 could be reduced. In other words, shifting taxable income from the future (high tax rate) period to the current (low tax rate) period can also achieve tax savings, and thus, firms should have an incentive to respond to a tax rate increase.

Despite the sparse prior evidence on upward tax management,2 understanding how firms respond to a tax rate increase is important for policymakers and the government because some jurisdictions may consider increasing their tax rates for a short period to pay for their fiscal budget deficits. Upward tax management, where taxable profits and the taxes thereon are recognized in the current (low taxed) period, goes against the original intent of the government. Investors and auditors may also have greater concerns over upward tax management than downward tax management because the upward tax management may be coupled with income-increasing discretionary accruals that are signals of opportunistic earnings management. Therefore, it is important to examine whether tax incentives, particularly those driven by a known future tax rate increase, motivate firms to engage in upward tax management.

To reduce the overall tax burden before an announced future tax rate increase, firms are likely to increase their current taxable income from future periods. In particular, firms can inflate taxable income and book income simultaneously (i.e., a book-tax conforming tax management),3 or they can manipulate their taxable income upward without managing their book income (i.e., a book-tax difference tax management, which we also call a book-tax non-conforming tax management in this paper).4 As discussed previously, prior studies generally find that firms use book-tax conforming earnings management to reduce taxable income before tax rates decrease (Guenther, 1994; Lopez et al., 1998; Maydew, 1997; Scholes et al., 1992; Adhikari et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2012). By the same token, one would intuitively expect that firms would use book-tax conforming earnings management to inflate their taxable income before tax rates increase. By doing so, firms can reduce their overall tax liabilities and, at the same time, reduce their financial reporting costs because of the higher book income reported. However, one drawback to using upward tax management via income-increasing discretionary accruals (i.e., a book-tax conformance treatment) before tax rates increase is that it increases the possibility of regulatory inspections of ostensibly over-aggressive financial reporting practices. For example, Kim et al. (2003) find that auditors are more likely to deter and monitor upward discretionary accruals than downward discretionary accruals. Therefore, whether companies will accelerate book income together with taxable income (i.e., book-tax conforming tax management) or just inflate the taxable income before a tax rate increase (i.e., book-tax difference tax management) awaits further investigation.5

We use Chinese listed companies for our study because China's institutional environment allows us to identify clearly firms that have high tax incentives to manipulate taxable income upward (or downward). The Chinese enterprise income tax rate is 33 per cent. However, the central and local governments of China offer firms a basket of tax incentives and tax holidays for a variety of reasons; for example, they offer tax holidays to encourage firms to restructure, to increase investment, or to encourage growth in selected industries (Deloitte, 2005). Therefore, different companies may be subject to different applicable tax rates during the same time period, and the applicable tax rates will increase or decrease in a particular year according to the tax preferential policies that the individual companies are entitled to.6 As the companies can anticipate the changes 1 year ahead, managers will be motivated to reduce the overall tax liabilities of their company by shifting taxable profits from a high tax rate period to a low tax rate period. Our data set enables us to examine upward tax management (i.e., before an impending tax rate increase) and to compare the results with downward tax management (i.e., before an impending tax rate decrease).

The first objective of our paper is to examine whether firms would increase their taxable income in a book-tax conforming or non-conforming manner when faced with a future increase in tax rates. We are particularly interested in investigating how tax incentives affect firms’ upward book management choices and how the financial reporting incentives interact with the tax incentives in affecting such earnings management decisions. If firms consider that reducing financial reporting costs is important (i.e., increasing reported earnings), they would use book-tax conforming tax management. If they consider that reducing regulatory inspection risk is important, they are more likely to use book-tax non-conforming upward tax management.

The second objective of our paper is to investigate how the trade-off between book management and tunneling7 incentives affect the reporting decisions by comparing the tax management strategies between the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the non-state-owned enterprises (NSOEs). Based on the unique institutional background in China, NSOEs should have higher earnings management incentives than SOEs (Chen et al., 2011), whereas SOEs have higher incentives to tunnel profits out from the companies than NSOEs (Lo and Wong, 2011). We expect that NSOEs (i.e., firms with high book management incentives) are more likely to increase their taxable income before a tax rate increment through book-tax conforming tax management because, despite the book income boosting, minimizing total taxation can be used as an excuse for opportunistic earnings management. However, when the benefits of managing taxable income upward outweigh the costs of doing so (e.g., increased regulatory inspection risks), firms would use book-tax non-conforming tax management. Therefore, we expect that SOEs are more likely to increase their taxable income before a tax rate increase through book-tax differences.

Our empirical findings suggest that firms adopt different forms of tax management before a tax rate increase vis-à-vis a tax rate decrease. Specifically, in the period just before a tax rate increment, we find that firms generally choose to increase their taxable income in a book-tax non-conforming way rather than in a book-tax conforming manner.8 In other words, firms tend to accelerate their taxable income alone and avoid the perception of overly aggressive financial reporting. However, when the firms’ book management incentives increase (or tunneling incentives decrease), we find that they use book-tax conforming methods to increase their taxable income for tax savings purposes. Our findings suggest that firms with high book management incentives (or low tunneling incentives) would be more likely to engage in book-tax conforming upward tax management than do firms with low book management incentives (or high tunneling incentives), and vice versa. Our findings are robust after controlling for the financial reporting costs, size, liquidity, growth, and year effects.

Our research makes three important contributions to the literature. First, our results on the choice of book-tax conforming and book-tax difference tax management show that, unlike in downward tax management, firms use book-tax non-conforming methods for upward tax management. Companies are willing to sacrifice financial reporting incentives and choose a method that can reduce their tax liabilities while keeping their book income steady before a tax rate increase. This implies that firms are more concerned about tax audit costs and the appearance of aggressive earnings management as signaled by large book-tax differences and discretionary accruals than financial reporting costs. Our findings help us to gain a better understanding of the choices that firms make for upward tax planning. Policymakers and regulators can gain more insights on firms’ reactions in anticipation of a tax rate increase, and this will help them to devise a tax policy that fits the financial needs of the government.

Second, we demonstrate how the trade-offs between various tax incentives, financial reporting incentives, and tunneling incentives influence managements’ opportunistic behaviors in corporate reporting. When firms are subject to high book management incentives (i.e., the NSOEs), they are more likely to use book-tax conforming tax management in response to a tax rate increase than do firms that are subject to low book management incentives (i.e., the SOEs). Our research provides new evidence from a tax perspective and highlights the interplay between tax incentives and various corporate reporting strategies, which should be helpful for financial statement users, accounting practitioners, and tax regulators as they assess firms’ reporting quality and tax planning activities.

Third, our findings suggest that book-tax differences are associated with upward tax management. These results provide new insights to help explain the informational content of book-tax differences and thus help answer an important research question of whether book-tax differences are informative about tax planning. Our findings show the important role played by book-tax differences in upward tax management and suggest possible research settings for future examinations of the informational content of book-tax differences.

We organize the remainder of this paper as follows. Section 2 provides the institutional background, and Section 2.1 formulates the research hypotheses. Section 2.2 discusses the data and model, and Section 3 describes the results. We present our conclusions in Section 3.1.

2 Institutional Background

2.1 Tax System and Tax Management in China

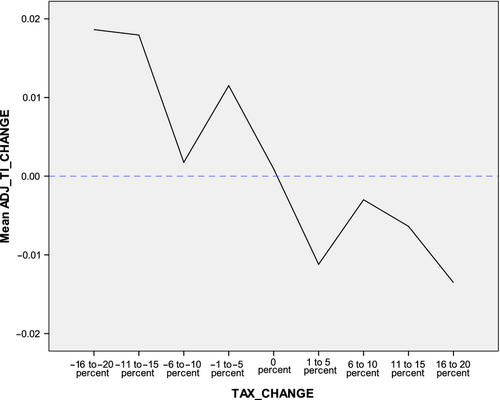

The Chinese enterprise income tax rate is 30 per cent, with an additional 3 per cent local tax (Deloitte, 2005). However, the central and local governments offer a basket of tax incentives and tax reductions to firms for a variety of reasons (e.g., to restructure, to encourage growth in selected industries, or to increase investment). For example, firms located in the western regions of the country are subject to an applicable tax rate of 15 per cent for a specified period (MOF (Ministry of Finance, PRC), 2001; Deloitte, 2005). Newly established or listed firms in state-encouraged industries can also enjoy tax holidays (i.e., tax exemption in the first 2 years and 50 per cent tax rate reduction in the following 3 years) (Liu, 2006). Therefore, domestic companies within China are subject to different applicable tax rates, and their applicable tax rates change according to the tax preferential policies that they are entitled to. To reduce tax liabilities, we believe that Chinese companies would shift their taxable income when tax rates change (no matter if it is a tax rate increase or decrease). Figure 1 illustrates the relation between a year-adjusted change in taxable income (ADJ_TI_CHANGEi,t; a firm's change in taxable income in year t minus the mean value of all sample firms’ change of taxable income in year t, where the change in taxable income in year t is equal to scaled taxable income in year t minus scaled taxable income in year t−1) and a change in tax rate (TAX_CHANGEi,t; a firm's applicable tax rate in year t minus the applicable tax rate in year t−1) of the sample firms we examine.9

- The x-axis represents a firm's tax rate change in year t, TAX_CHANGE, and we categorize it into nine categories. The y-axis is the mean of ADJ_TI_CHANGE for each category of TAX_CHANGE.

- Variable Definitions:

- ADJ_TI_CHANGEi,t = year-adjusted taxable income changes (scaled by a firm's total asset) (i.e., a firm's change in taxable income in year t minus the mean value of all sample firms’ change of taxable income in year t, where the change in taxable income in year t is equal to scaled taxable income in year t minus scaled taxable income in year t−1).

- TAX_CHANGEi,t = a firm's tax rate changes in year t (i.e., tax rate in year t minus tax rate in year t−1).

As illustrated in Figure 1, the change in taxable income (ADJ_TI_CHANGEi,t) has a positive value when the tax rate decreases (i.e., TAX_CHANGEi,t < 0). In contrast, the change in taxable income (ADJ_TI_CHANGEi,t) has a negative value when the tax rate increases (i.e., TAX_CHANGEi,t > 0). Put differently, this preliminary analysis suggests that firms that anticipate a tax rate decrease in year t−1 shift their taxable income from year t−1 to year t, and it results in a positive change (i.e., an increase) in taxable income in year t. Conversely, firms that anticipate a tax rate increase in year t−1 shift their taxable income from year t to year t−1, and it results in a negative change (i.e., a decrease) in taxable income in year t. Both income-shifting behaviors lead to a reduction in a firm's overall tax liabilities, which provide evidence to support our argument that firms engage in tax management practices regardless of tax rate decreases or increases.

As the Chinese accounting rules and tax rules were delinked in 2001, Chinese firms can use the book-tax conforming or the book-tax non-conforming method to engage in tax management. Wu et al. (2007) find that Chinese firms’ effective tax rates are very different from the applicable tax rates in 2001 and 2002 and that a firm's taxable income is significantly different from its book profits. Chan et al. (2010) find that firms can manage their income in both book-tax conforming and book-tax non-conforming manners. For example, a firm can accelerate recognizing its sales or defer the deduction of book-tax conforming expenses to increase its taxable income conformingly. Alternatively, a firm can increase its current taxable income in a book-tax difference manner by deferring the payment of a performance-linked bonus. In China, the provision for a performance-linked bonus is deductible for accounting purposes. However, such a provision is not tax deductible, as a firm can only deduct a performance-linked bonus in its tax return when the amount is paid. Besides, a firm can also defer its sale of devalued inventories to increase current year taxable income non-conformingly because a firm can only deduct provisions for the devaluation of inventories in its tax return when the inventories are sold. Overall, we believe that conforming and non-conforming tax management is a choice by the company, and thus, it is important to examine how this choice is affected by various tax and financial reporting incentives.

2.2 Ownership Structure of Listed Companies in China

The unique ownership structure of listed companies in China creates different types of incentives to manage book earnings. Since the economic reform in 1990s, many profitable units of state enterprises have been spun-off and listed on the stock exchange. After the listing, the state government (i.e., the parent companies) typically retains substantial shareholdings and effectively controls the listed SOEs, while retaining the unprofitable units of the business as well as the social activities (e.g., hospitals, schools, etc.) (Ding et al., 2011). The poor-performing divisions and social service units need financial support from the listed SOEs. Therefore, the managements of the listed SOEs are likely to tunnel profits out to their parent companies to support the poor-performing divisions and non-revenue generating units (Lo and Wong, 2011). As SOEs need to tunnel profits out, they need to sacrifice financial reporting incentives and report lower profits. In addition, SOEs are likely to have weaker incentives to manage accounting performance than NSOEs (Chen et al., 2011). The shares of the listed SOEs held by the parent companies are mainly non-tradable shares (i.e., shares that cannot be sold freely in the stock market), and thus, parent companies cannot enjoy the benefit from the appreciation of share prices (Green, 2003; Jiang and Wang, 2008). Additionally, state-controlled firms have better access to bank loans and find it easier to issue additional shares when compared to non-state-controlled firms, and they have less need to convince skeptical investors by reporting increased book profits. Thus, state-controlled listed firms have a lesser need to inflate their book numbers via earnings management. In conclusion, the distinct differences in ownership structure in China create different incentives for earnings manipulations. In particular, SOEs have higher tunneling incentives and lower book management incentives than do NSOEs.

3 Hypothesis Development

3.1 Strategies for Upward Tax Management

Previous studies have shown that a future tax rate change can significantly influence the financial reporting behavior of managers in achieving tax savings (Lopez et al., 1998; Maydew, 1997; Scholes et al., 1992; Adhikari et al., 2005). For example, some U.S. studies have found that firms manage their discretionary accruals10 in response to tax rate changes caused by the U.S. 1986 Tax Reform Act, and shift their book profits to periods with lower corporate tax rates (Guenther, 1994; Lopez et al., 1998; Yin and Cheng, 2004). In addition to the U.S. studies cited above, Roubi and Richardson (1998) find that non-manufacturing firms in Canada, Malaysia, and Singapore also manage their discretionary accruals for tax saving purposes. Analyzing a data set of Chinese firms, Lin et al. (2012) find that firms facing a tax rate reduction have lower discretionary accruals than do other firms. These studies show that firms shift their taxable profits in a book-tax conforming manner to take advantage of an anticipated tax rate reduction. It is important to note that firms that engage in book-tax conforming management before a tax rate reduction give more weight to tax incentives than to financial reporting incentives (Guenther, 1994). That is, they are willing to incur financial reporting costs (e.g., by reducing their book income) to achieve tax savings.

Similarly, in the period before a tax rate increment, firms may also choose to increase their taxable income book-tax conformingly to reduce their tax liabilities. By utilizing book-tax conforming upward tax management before a tax rate increment, firms can shift their taxable income from the next year to the current year to reduce their total tax liabilities, and at the same time report a higher book income. Therefore, firms can enjoy both tax savings and financial reporting benefits (because of higher reported income) by boosting their book and taxable income together before a tax rate increase. Firms can even use tax planning as a means to prop up income to hide bad news (Wong et al., 2015). Accordingly, we expect that firms will increase their taxable income through book-tax conforming earnings management to take advantage of the anticipated tax rate increment as well as to boost their book income if they place more weight on the financial reporting incentives.

Another tax management choice in response to tax rate increases is engaging in book-tax non-conforming management. Owing to differences between the accounting standards and tax regulations, firms can also achieve tax savings by manipulating their taxable income without managing their book income (Frank et al., 2009; Heltzer, 2009). As suggested by McGill and Outslay (2004), Plesko (2004), and Shevlin (2002), an ideal tax shelter will help reduce a firm's taxable income without affecting its financial reporting income. If so, it is possible that Chinese listed firms will shift their taxable income upward through book-tax non-conforming management for tax purposes. By doing so, a firm can reduce its tax liabilities while keeping its book income unaffected. As Kim et al. (2003) suggest, external auditors are more likely to deter and monitor income-increasing accruals than income-decreasing accruals. Therefore, in the period before a tax rate increase, having book-tax non-conforming earnings may receive less attention from external monitoring bodies than book-tax conforming earnings. Moreover, firms that have large book-tax differences can reduce the differences by increasing taxable income alone, which in turn would help them reduce their tax audit risks and avoid other negative consequences to firm value that might arise from large book-tax differences (Ayers et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2010; Hanlon, 2005; Lev and Nissim, 2004; Mills, 1998). Here, firms engaging in book-tax non-conforming management need to sacrifice their financial reporting incentives.

H1a: (reduction of financial reporting cost) Companies will increase their taxable income before a tax rate increment through book-tax conforming tax management, resulting in larger book-tax conforming discretionary accruals.

H1b: (reduction of tax audit and regulatory inspection risk) Companies will increase their taxable income before a tax rate increment through book-tax difference tax management, resulting in smaller11 book-tax differences.

3.2 Tax Management Strategies for SOEs and NSOEs

Prior studies suggest that firms adopt different reporting strategies to balance various corporate objectives. For example, some tax studies find that firms forgo financial reporting costs, and reduce book and taxable income simultaneously for tax planning purposes (e.g., Klassen, 1997). Prior research on financial reporting finds that some firms would incur additional tax costs and increase book and taxable income together for higher reported profits (e.g., Erickson et al., 2004), whereas other firms would engage in book-tax non-conforming earnings management to avoid earnings declines or losses (e.g., Phillips et al., 2003). However, very few studies investigate the impact of firm characteristics on the choice between conforming and non-conforming reporting decisions. One exception is Badertscher et al. (2009) who find that firms with a net operating loss (i.e., with low tax costs) and that employ high-quality auditors (i.e., have high expected detection costs) are more likely to boost book income conformingly than non-conformingly for financial reporting purposes.

Our study differs from Badertscher et al. (2009) in that we investigate how firm characteristics affect tax management strategies. Specifically, we examine the trade-off between book management incentives and tunneling incentives on the choice between book-tax conforming and non-conforming tax management. Based on the institutional background in China, listed companies are classified into SOEs and NSOEs. As explained earlier, the NSOEs have higher incentives to manage their book income upward for financial reporting purposes, such as avoiding an earnings decline, avoiding losses, and increasing management remuneration, when compared to SOEs (Chen et al., 2011). Therefore, we expect that NSOEs are likely to use tax planning as an excuse for managing their book earnings upward. For example, before a tax rate increase, if the managements of NSOEs want to manage book income to increase their remuneration, they can boost the companies’ book and taxable income simultaneously, and use tax planning to cover up their real book management motives. Accordingly, we expect that NSOEs are more likely to manage their taxable income book-tax conformingly before a tax rate increase and thus have higher discretionary accruals than do SOEs.

H2a: NSOEs are more likely to increase their taxable income before a tax rate increment through book-tax conforming tax management, resulting in larger book-tax conforming discretionary accruals than do SOEs.

H2b: SOEs are more likely to increase their taxable income before a tax rate increment through book-tax difference tax management, resulting in smaller book-tax differences than do NSOEs.

4 Research Method

Our sample comprises all the companies that are listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange from 2001 to 2006.13 The tax incentives and applicable tax rates of listed companies are manually collected from the footnotes of the companies’ annual reports (5 firms are excluded due to missing tax data). Those companies that have no taxes to be paid are excluded (243 companies are excluded for this reason). We then collect other financial data of the companies from the Wind Financial Database and the CSMAR Database. Companies with missing variables and those in the financial services industries are excluded (124 companies are excluded for these reasons). The final sample that meets all our criteria consists of 438 listed companies, equivalent to 2,628 firm-year observations.

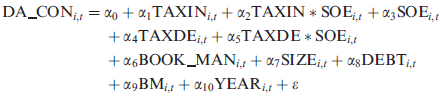

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

(3)Following previous tax research, we limit discretionary accruals to that portion of current accruals (CACCi,t) most directly related to taxable income, such that it reflects the discretionary accruals that affect taxable income (Guenther, 1994; Lin, 2006; Lopez et al., 1998; Roubi and Richardson, 1998).14 We obtain the non-discretionary component of current accruals from Model (3), where the regression parameters are estimated using cross-sectional observations for each year and industry (we use the standard industry classification compiled by the China Securities Regulatory Commission [CSRC]; we exclude industries with < 10 observations). ∆SALEi,t represents the change in sales, ∆ARi,t represents the change in accounts receivable, and PPEi,t represents the firm's gross property, plant, and equipment in year t. Following Kasznik (1999) and Kim et al. (2003), we include the change in cash flow from operations (∆CFOi,t) in the modified Jones model. All the variables are scaled by the lagged total assets (TAi,t−1).

We note that the discretionary accruals employed in previous studies (e.g., Guenther, 1994; Lin, 2006; Lopez et al., 1998; Yin and Cheng, 2004) include not only the accruals that affect both book and taxable income but also those that affect only book or only taxable income (e.g., bad debt accruals) (Lev and Nissim, 2004). In addition, if a firm defers recognizing non-tax deductible expenses to increase its book income, keeping taxable income unaffected, both the current accruals (CACCi,t) and book-tax differences (BT_DIFFi,t) will increase. Our study uses an alternative approach to estimate the book-tax conforming portion of discretionary accruals. Here, we include a firm's book-tax differences (BT_DIFFi,t) in Model (3) to control for the accruals arising from book-tax differences. BT_DIFFi,t measures the book-tax difference of firm i in year t; it is measured by the difference between the before-tax financial profits and taxable profits (scaled by the firm's total assets).15 The residuals obtained from the fitted Model (3) represent the book-tax conforming discretionary accruals (i.e., DA_CONi,t). The dependent variable for Model (2), BT_DIFFi,t, is the same as the independent variable, BT_DIFFi,t, in Model (3). A positive (negative) book-tax difference represents cases where the book income is greater (smaller) than the taxable income.16

The variable of interest in Model (1) and Model (2), TAXINi,t, is a dummy variable, which captures the firm's tax incentives to increase its taxable income in the current year t. TAXINi,t is set equal to 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t + 1, and 0 otherwise. Firms are able to anticipate tax rate increases as they are scheduled well in advance. As hypothesized in H1a, companies that anticipate a tax rate increase are likely to increase their taxable income along with their book income, resulting in greater book-tax conforming discretionary accruals. Therefore, we expect a positive association between TAXINi,t and DA_CONi,t in Model (1). As hypothesized in H1b, we expect a negative coefficient on TAXINi,t in Model (2), because there would be smaller book-tax differences from managing taxable income upward without a concomitant increase in book income in the period prior to a tax rate increment. The coefficient on TAXINi,t would be insignificant in Model (1) (Model [2]) if the firms do not accelerate their taxable income through book-tax conforming (book-tax non-conforming) management.

The first control variable, TAXDEi,t, is a dummy variable, which captures the firm's tax incentives to decrease its taxable income in the current year t. TAXDEi,t is equal to 1 if the firm's tax rate decreases in year t + 1, and 0 otherwise. Following the prior literature, we expect a negative coefficient on TAXDEi,t in Model (1). If firms also use book-tax non-conforming methods for reducing taxable income before a tax rate reduction, we expect there to be a positive association between TAXDEi,t and BT_DIFFi,t in Model (2).

The second control variable, BOOK_MANi,t, is a dummy variable capturing the likelihood that a firm has engaged in earnings management for financial reporting purposes. Phillips et al. (2003) find that firms manage their book income to avoid reporting losses. This behavior is especially pertinent in China. Jiang and Wang (2008) find that the percentage of Chinese listed firms with small profits is significantly higher than the percentage of firms with small losses. The difference between the percentages of the small loss and small profit companies in China is about 10 times that in the United States. These findings provide some evidence that Chinese listed companies engage in book management to achieve at least small profits and thereby avoid losses. In addition, as listed companies cannot report losses for three consecutive years or otherwise their shares will be suspended and delisted (CSRC (China Securities Regulatory Commission), 2001), Chinese listed companies have high incentives to avoid losses and reduce the chances of being delisted.

Another important financial reporting cost borne by Chinese listed firms relates to the return on equity (ROE) thresholds for issuing new capital (Jian and Wong, 2010; Liu and Lu, 2007). In China, listed firms have to meet certain profitability requirements of the stock exchange to issue new equity capital. Firms should have an average ROE of 6 per cent or more over the 3 years preceding a rights issue to their existing shareholders, an average ROE of 10 per cent or more for the 3 years before a share placement to the public, and a minimum ROE of 10 per cent for the year immediately before a share placement (CSRC (China Securities Regulatory Commission), 2002; Shanghai Stock Exchange, 2004). Therefore, the managers of listed firms are keen to maintain these minimum ROE requirements to increase their financial flexibility. We believe that firms with ROEs just above 0, 6, or 10 per cent or firms that issue new shares in the following year are more likely to have engaged in earnings management for financial reporting purposes. Therefore, we include a dummy variable, BOOK_MANi,t, to control for these effects. BOOK_MANi,t is equal to 1 if (i) a firm's ROE17 is between 0 and 1.5 per cent (i.e., just above the delisting earnings threshold), (ii) a firm's ROE is between 6 and 7.5 per cent, or between 10 and 11.5 per cent (i.e., just above the earnings thresholds for issuing new shares), or (iii) a firm issues new shares in the following year; it is 0 otherwise. Given that firms can manage their book income upward book-tax conformingly or non-conformingly, we expect the coefficients on BOOK_MANi,t to be positive in both Model (1) and Model (2).

Previous studies have found that the size and leverage of firms have significant impacts on their book-tax differences and discretionary accruals (Guenther, 1994; Mills and Newberry, 2001; Rego, 2003). For example, Mills and Newberry (2001) show that public firms of larger size and lower leverage have larger book-tax differences. Guenther (1994) shows that firms of larger size and lower leverage are more likely to defer their profits in the year prior to a tax rate reduction and thus have smaller discretionary accruals than firms of smaller size and higher leverage. Therefore, we include SIZEi,t (measured by the natural logarithm of total sales) and DEBTi,t (measured by the long-term debt to asset ratio) in our regression models. We expect that SIZEi,t will be positively (negatively) associated with BT_DIFFi,t (DA_CONi,t), whereas DEBTi,t will be negatively (positively) associated with BT_DIFFi,t (DA_CONi,t).

We also follow the previous literature and control for a firm's growth, BMi,t, on corporate reporting decisions (Badertscher et al., 2009). BMi,t is measured by a firm's book-to-market equity ratio. In addition, we include BT_DIFFi,avg in Model (2) to control for the effect of book-tax differences in individual firms. BT_DIFFi,avg is the average of book-tax differences of firm i in the sample period 2001–2006. We assume that non-discretionary book-tax differences should remain stable over time. Thus, BT_DIFFi,avg reflects the firm's “normal” book-tax differences due to differences between tax and accounting reporting practices. Finally, we include YEARi,t (year dummies) to control for the yearly fixed effects in both models.

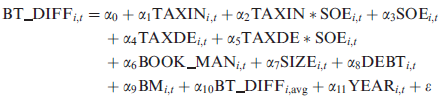

(4)

(4) (5)

(5)Our main variable of interest, TAXIN*SOEi,t, is the interaction term of TAXINi,t and SOEi,t. SOEi,t is equal to 1 if a firm's largest shareholder is the Chinese government; and 0 otherwise. As hypothesized in H2a, NSOEs are more likely to have book-tax conforming upward tax management, and thus, we expect a negative association between DA_CONi,t and TAXIN*SOEi,t in Model (4). As hypothesized in H2b, SOEs are more likely to have book-tax non-conforming tax upward management and we therefore expect a positive association between BT_DIFFi,tand TAXIN*SOEi,t in Model (5).

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 Panel A reports the descriptive statistics of the 2,628 sample observations. The mean and median of book-tax differences (BT_DIFFi,t) are −0.010 and −0.001, respectively. The mean and median of book-tax conforming discretionary accruals (DA_CONi,t) are 0.002 and 0.009, respectively. Panel A also reports that 9.2 per cent of the sample observations expect a tax rate increase in the following year and 2.5 per cent expect a tax rate reduction. About 32 per cent of the observations are likely to have managed their book income for meeting earnings targets (BOOK_MANi,t) within our sample period.

| Panel A: Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | |

| DA_CONi,t | 0.002 | 0.157 | −0.058 | 0.009 | 0.070 |

| BT_DIFFi,t | −0.010 | 0.051 | −0.015 | −0.001 | 0.009 |

| TAXINi,t | 0.092 | 0.289 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| TAXDEi,t | 0.025 | 0.157 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| BOOK_MANi,t | 0.323 | 0.468 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SIZEi,t | 20.626 | 1.255 | 19.833 | 20.543 | 21.385 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.068 | 0.094 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.096 |

| BMi,t | 0.518 | 0.327 | 0.298 | 0.457 | 0.674 |

| BT_DIFFi,avg | −0.010 | 0.029 | −0.019 | −0.005 | 0.006 |

| Panel B: Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA_CONi,t | BT_DIFFi,t | TAXINi,t | TAXDEi,t | BOOK_MANi,t | SIZEi,t | DEBTi,t | BMi,t | BT_DIFFi,avg | |

| DA_CONi,t | 1.000 | ||||||||

| BT_DIFFi,t | −0.026** | 1.000 | |||||||

| TAXINi,t | 0.019 | −0.063*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| TAXDEi,t | −0.051*** | 0.026 | −0.051*** | 1.000 | |||||

| BOOK_MANi,t | 0.002 | 0.031 | −0.028 | −0.002 | 1.000 | ||||

| SIZEi,t | −0.001 | 0.050*** | −0.049*** | −0.009 | −0.017 | 1.000 | |||

| DEBTi,t | 0.055*** | 0.030** | 0.005 | 0.000 | −0.005 | 0.058*** | 1.000 | ||

| BMi,t | 0.020 | −0.027** | −0.113*** | −0.021 | 0.001 | 0.244*** | 0.073*** | 1.000 | |

| BT_DIFFi,avg | 0.003 | 0.474*** | 0.005 | −0.007 | 0.031 | 0.097*** | 0.060*** | 0.026** | 1.000 |

- ***and ** indicate significance at the 1 per cent and 5 per cent levels, respectively (two-tailed), using Kendall's tau_b correlation tests.

-

Variable Definitions:

- BT_DIFFi,t = a firm's book-tax reporting difference (book income minus taxable income) divided by the firm's total assets in year t.

- DA_CONi,t = a firm's book-tax conforming discretionary current accruals.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- BT_DIFFi,avg = a firm's average BT_DIFFi,t for the sample period 2001 to 2006.

Panel B shows the correlation matrix among the selected variables of the regression models, Model (1) and Model (2). We find that TAXDEi,t is negatively correlated with DA_CONi,t, but not significantly correlated with BT_DIFFi,t. Conversely, TAXINi,t is negatively correlated with BT_DIFFi,t, but not significantly correlated with DA_CONi,t. These results give preliminary evidence that firms choose different earnings management methods in response to tax rate increments or reductions. We also find that firms with larger size (SIZEi,t), higher debt ratio (DEBTi,t), and higher growth (represented by smaller BMi,t) are correlated with larger book-tax differences. Firms with a higher debt ratio (DEBTi,t) are correlated with larger book-tax conforming discretionary accruals. Correlations among the independent variables are generally quite low.

5.2 Univariate Tests

Table 2 shows the univariate test results for book-tax difference and book-tax conforming discretionary accruals of firms with tax incentives to manage taxable income. As shown in the table, firms that have tax incentives to manage their taxable profits upward (i.e., before a tax rate increase) have significantly smaller book-tax differences than other firms (p-value < 0.001). Table 2 also shows that firms that have tax incentives to manage their taxable profits downward (i.e., before a tax rate reduction) have significantly smaller book-tax conforming discretionary accruals than those that have no such incentives (p-value < 0.001). We also find that firms that are likely to have engaged in earnings management for financial reporting purposes (BOOK_MANi,t = 1) have larger book-tax differences than those that have not manipulated book earnings. Taken together, the univariate tests suggest that although firms opt to use book-tax conforming discretionary accruals to reduce their taxable income (along with book income) in the period before a tax rate reduction, they choose to increase their taxable income via book-tax difference management in the period before a tax rate increment.

| Variables | Definition | No. of Firms | DA_CONi,t Mean | t-test | BT_DIFFi,t Mean | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAXINi,t | If a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1 | 241 | 0.014 | 1.250 | −0.020 | −3.355*** |

| Otherwise | 2,387 | 0.001 | −0.009 | |||

| TAXDEi,t | If a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1 | 66 | −0.055 | −3.004*** | −0.007 | 0.400 |

| Otherwise | 2,562 | 0.038 | −0.010 | |||

| BOOK_MANi,t | If return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year | 848 | 0.002 | −0.039 | −0.002 | 5.671*** |

| Otherwise | 1,780 | 0.002 | −0.014 |

- ***indicates significance at the 1 per cent level (two-tailed).

-

Variable Definitions:

- BT_DIFFi,t = a firm's book-tax reporting difference (book income minus taxable income) divided by the firm's total assets in year t.

- DA_CONi,t = a firm's book-tax conforming discretionary current accruals.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

5.3 Regression Results

5.3.1 Upward tax management strategies

Table 3 reports the regression results for Model (1), and Table 4 reports the results for Model (2). We base the t-statistics on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms. Table 3 shows that there is no significant association between TAXINi,t and DA_CONi,t, whereas Table 4 shows that TAXINi,t and BT_DIFFi,t are negatively associated at the 1 per cent level. The results support hypothesis H1b and suggest that firms choose to use book-tax non-conforming rather than book-tax conforming tax management before a tax rate increase (for upward tax management). Prior studies have suggested that large book-tax differences are “red flags” to tax authorities, investors, and credit rating agencies (e.g., Ayers et al., 2010; Hanlon, 2005; Lev and Nissim, 2004; Wilson, 2009). By increasing their taxable income without affecting their book income, firms can reduce their book-tax differences (book income minus taxable income) and thereby reduce the risk of being audited by the tax authorities (Mills and Sansing, 2000), and incurring the negative impacts of increased book-tax differences on their credit ratings (Ayers et al., 2010; Crabtree and Maher, 2009). In addition, avoiding overstating the book income of firms can reduce the regulatory detection risks (i.e., sanction risks) associated with over-aggressive financial reporting practices (Feroz et al., 1991; Firth et al., 2005). Therefore, firms are willing to forgo financial reporting benefits and increase their taxable income through book-tax non-conforming methods, and further reduce their book-tax differences and save tax before a tax rate increase.

| DA_CONi,t = α0 + α1TAXINi,t + α2TAXDEi,t + α3BOOK_MANi,t + α4 SIZEi,t + α5DEBTi,t + α6BMi,t + α7YEARi,t + ɛ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Predicted Sign | Regression Coeff. | t-stat |

| Intercept | −0.008 | −0.139 | |

| TAXINi,t | + | 0.000 | 0.044 |

| TAXDEi,t | − | −0.056 | −3.442*** |

| BOOK_MANi,t | + | 0.000 | 0.034 |

| SIZEi,t | − | −0.002 | −0.541 |

| DEBTi,t | + | 0.165 | 5.551*** |

| BMi,t | ? | 0.004 | 0.405 |

| YEARi,t | ? | Included | |

| Adjusted R square | 0.019 | ||

| F statistic | 5.760*** | ||

- ***indicates significance at the 1 per cent level.

- Significances are based on a one- (two-) tailed test when the coefficient sign is (not) predicted.

- The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

-

Variable Definitions:

- DA_CONi,t = a firm's book-tax conforming discretionary current accruals.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- YEARi,t = a vector of year dummy variables from 2001 to 2006.

| BT_DIFFi,t = α0 + α1TAXINi,t + α2TAXDEi,t + α3BOOK_MANi,t + α4 SIZEi,t + α5DEBTi,t + α6BMi,t + α7BT_DIFFi,avg + α8YEAR + ɛ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Predicted Sign | Regression Coeff. | t-stat |

| Intercept | −0.035 | −2.176 | |

| TAXINi,t | − | −0.016 | −5.145*** |

| TAXDEi,t | + | 0.002 | 0.198 |

| BOOK_MANi,t | + | 0.008 | 6.254*** |

| SIZEi,t | + | 0.001 | 1.958** |

| DEBTi,t | − | 0.004 | 0.452 |

| BMi,t | ? | 0.004 | 1.193 |

| BT_DIFFi,avg | + | 0.978 | 15.907*** |

| YEARi,t | ? | Included | |

| Adjusted R square | 0.353 | ||

| F statistic | 120.600*** | ||

- *** and **indicate significance at the 1 per cent and 5 per cent levels, respectively.

- Significances are based on a one- (two-) tailed test when the coefficient sign is (not) predicted.

- The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

-

Variable Definitions:

- BT_DIFFi,t = a firm's book-tax reporting difference (book income minus taxable income) divided by the firm's total assets in year t.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- BT_DIFFi,t-avg = a firm's average BT_DIFFi,t for the sample period 2001 to 2006.

- YEARi,t = a vector of year dummy variables from 2001 to 2006.

Consistent with the results of prior studies on downward tax management, Table 3 shows that TAXDEi,t is negatively significant at the 1 per cent level. This result suggests that firms would reduce their discretionary accruals before a tax rate reduction. We also find that there is no significant association between TAXDEi,t and BT_DIFFi,t (as shown in Table 4). Taken together, these results suggest that firms choose to use book-tax conforming tax management rather than book-tax non-conforming tax management before a tax rate reduction (for downward tax management). Overall, although reducing discretionary accruals in a book-tax conforming manner would increase a firm's financial reporting costs, our empirical evidence shows that firms are willing to do so to enjoy the tax savings therefrom.

In summary, the results in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that firms use different methods for downward versus upward tax management. To reduce their book-tax differences (and associated tax audit risk), firms manipulate their taxable income through book-tax conforming downward tax management, even though this will increase their financial reporting costs. As for upward tax management, firms will manipulate their taxable earnings through book-tax differences rather than through book-tax conformance. Although book-tax conformance reflects more on downward tax management and book-tax differences reflect more on upward tax management, overall, our results demonstrate that reducing tax liabilities (as well as reducing detection costs for tax and book management) is more important than reducing financial reporting costs when it comes to tax management in China.

Table 3 also shows that there is no significant association between BOOK_MANi,t and DA_CONi,t, whereas Table 4 shows that BOOK_MANi,t is positively significant at the 1 per cent level. These results suggest that firms will boost their income for financial reporting purposes through book-tax difference management (instead of book-tax conforming management). Put differently, book-tax differences may also reflect book-induced upward earnings management. These results are consistent with the findings of Badertscher et al. (2009) who show that non-conforming earnings management is more prevalent than conforming earnings management for book-induced earnings management. In addition, our results show that book-tax conforming discretionary accruals are positively associated with DEBTi,t (Table 3), while book-tax differences are positively correlated with SIZEi,t and BT_DIFFi,avg (Table 4).

5.3.2 Tax management strategies for SOEs and NSOEs

Table 5 provides the descriptive statistics for SOEs versus NSOEs. The table shows that the book-tax conforming discretionary accruals and the book-tax differences are not significantly different between SOEs and NSOEs. Approximately 8.8 per cent of SOEs have a tax rate increase and 2.2 per cent of SOEs have a tax rate decrease. Although the percentages of NSOEs that have a tax rate increase and decrease are slightly higher than those of SOEs (i.e., 10.3 per cent and 3.5 per cent, respectively), the differences are not statistically significant. Table 5 also shows that SOEs and NSOEs have similar liquidity ratios (DEBTi,t) and growth rates (BMi,t), but SOEs have larger sizes (SIZEi,t) than do NSOEs.

| Variables | SOEs | NSOEs | t-stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| DA_CONi,t | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.146 |

| BT_DIFFi,t | −0.010 | −0.011 | 0.462 |

| TAXINi,t | 0.088 | 0.103 | −1.252 |

| TAXDEi,t | 0.022 | 0.035 | −1.843 |

| BOOK_MANi,t | 0.319 | 0.332 | −0.606 |

| SIZEi,t | 20.774 | 20.216 | 10.264*** |

| DEBTi,t | 0.070 | 0.063 | 1.788 |

| BMi,t | 0.525 | 0.499 | 1.804 |

| BT_DIFFi,avg | −0.010 | −0.010 | 0.727 |

- ***indicate significance at the 1 per cent level.

-

Variable Definitions:

- DA_CONi,t = a firm's book-tax conforming discretionary current accruals.

- BT_DIFFi,t = a firm's book-tax reporting difference (book income minus taxable income) divided by the firm's total assets in year t.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- BT_DIFFi,t-avg = a firm's average BT_DIFFi,t for the sample period 2001 to 2006.

Tables 6 and 7 report the regression results of Models (4) and (5), respectively. Table 6 shows that the coefficient on TAXINi,t is positively significant at the 5 per cent level. As hypothesized in H2a, we find that the coefficient on the interaction term, TAXIN*SOEi,t, is negatively significant at the 5 per cent level. The summation of the coefficient on TAXINi,t (0.043) and the interaction term TAXIN*SOEi,t (−0.049) is not statistically different from zero. This means that NSOEs have higher conforming discretionary accruals before a tax rate increase, whereas SOEs do not. This suggests that NSOEs are more likely to use conforming discretionary accruals to boost their taxable income before a tax rate increase. SOEs, on the other hand, have weaker book management incentives than do NSOEs. Therefore, they are less likely to manipulate conforming discretionary accruals before a tax rate increase.

| DA_CONi,t = α0 + α1TAXINi,t + α2TAXIN * SOEi,t + α3SOEi,t + α4 TAXDEi,t + α5TAXDE * SOEi,t + α6BOOK_MANi,t + α7SIZEi,t + α8DEBTi,t + α9BMi,t + α10YEARi,t + ɛ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Predicted Sign | Regression Coeff. | t-stat |

| Intercept | −0.059 | −1.119 | |

| TAXINi,t | + | 0.043 | 2.140** |

| TAXIN*SOEi,t | − | −0.049 | −2.119** |

| SOEi,t | ? | 0.001 | 0.112 |

| TAXDEi,t | − | −0.069 | −2.177** |

| TAXDE*SOEi,t | ? | 0.016 | 0.398 |

| BOOK_MANi,t | + | 0.002 | 0.296 |

| SIZEi,t | − | 0.000 | 0.109 |

| DEBTi,t | + | 0.171 | 5.308*** |

| BMi,t | ? | 0.007 | 0.606 |

| YEARi,t | ? | Included | |

| Adjusted R square | 0.041 | ||

| F statistic | 8.996*** | ||

- *** and ** indicate significance at the 1 and 5 per cent levels, respectively.

- Significances are based on a one- (two-) tailed test when the coefficient sign is (not) predicted.

-

Variable Definitions:

- DA_CONi,t = a firm's book-tax conforming discretionary current accruals.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- SOEi,t = 1 if a firm's largest shareholder is the Chinese government; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- YEARi,t = a vector of year dummy variables from 2001 to 2006.

| BT_DIFFi,t = α0 + α1TAXINi,t + α2TAXIN * SOEi,t + α3SOEi,t + α4 TAXDEi,t + α5TAXDE * SOEi,t + α6BOOK_MANi,t + α7SIZEi,t + α8DEBTi,t + α9BMi,t + α10BT_DIFFi,avg + α11YEARi,t + ɛ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Predicted Sign | Regression Coeff. | t-stat |

| Intercept | −0.035 | −2.410** | |

| TAXINi,t | − | −0.017 | −3.279*** |

| TAXIN*SOEi,t | − | 0.002 | 0.295 |

| SOEi,t | ? | −0.002 | −1.055 |

| TAXDEi,t | + | −0.016 | −1.862 |

| TAXDE*SOEi,t | ? | 0.027 | 2.545** |

| BOOK_MANi,t | + | 0.008 | 4.858*** |

| SIZEi,t | + | 0.001 | 2.109** |

| DEBTi,t | − | 0.003 | 0.331 |

| BMi,t | ? | 0.004 | 1.478 |

| BT_DIFFi,avg | + | 0.968 | 34.927*** |

| YEARi,t | ? | Included | |

| Adjusted R square | 0.350 | ||

| F statistic | 95.286*** | ||

- ***and **indicate significance at the 1 and 5 per cent levels, respectively.

- Significances are based on a one- (two-) tailed test when the coefficient sign is (not) predicted.

-

Variable Definitions:

- BT_DIFFi,t = a firm's book-tax reporting difference (book income minus taxable income) divided by the firm's total assets in year t.

- TAXINi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate increases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- SOEi,t = 1 if a firm's largest shareholder is the Chinese government; 0 otherwise.

- TAXDEi,t = 1 if a firm's tax rate decreases in year t+1; 0 otherwise.

- BOOK_MANi,t = 1 if return on equity of the firm is between 0 and 1.5 per cent, 6 and 7.5 per cent, or 10 and 11.5 per cent, or the firm issues new shares in the following year; 0 otherwise.

- SIZEi,t = natural logarithm of total sales.

- DEBTi,t = long-term debt to assets ratio.

- BMi,t = book to market value of a firm's equity.

- BT_DIFFi,t-avg = a firm's average BT_DIFFi,t for the sample period 2001 to 2006.

- YEARi,t = a vector of year dummy variables from 2001 to 2006.

Table 7 reports the regression results of Model (5). Overall, the results are qualitatively similar to the results of Model (2) as reported in Table 4. The coefficient on TAXINi,t is negatively significant at the 1 per cent level, whereas TAXDEi,t is not statistically significant and BOOK_MANi,t is positively significant. We also find that the coefficient on SOEi,t and the interaction term TAXIN*SOEi,t are not statistically significant in the model. The findings suggest that book management and tunneling incentives do not have a significant impact on firms’ non-conforming upward tax management. Both SOEs and NSOEs have lower book-tax differences before a tax rate increase. Table 7 also shows that TAXDE*SOEi,t is positively significant at the 5 per cent level, which implies that SOEs are more likely to decrease taxable income non-conformingly than do NSOEs before a tax rate decrease. In other words, although the earnings management and tunneling incentives do not influence non-conforming upward tax management, they have significant impacts on non-conforming downward tax management.

5.4 Sensitivity Tests

We conduct several additional tests to check the robustness of the main regression results. First, we adjust BT_DIFFi,t by the average value of a firm's book-tax differences. Here, we replace the dependent variable of Model (2) BT_DIFFi,t by BT_DIFFi,t-avg and exclude the independent variable BT_DIFFi,avg from Model (2).18 BT_DIFFi,t-avg is equal to BT_DIFFi,t minus BT_DIFFi,avg. The results of this sensitivity test are qualitatively similar to the original results of Model (2). TAXINi,t is negatively associated with BT_DIFFi,t-avg at the 1 per cent level, while TAXDEi,t is not significantly correlated with BT_DIFFi,t-avg.

Second, we replace the dependent variable of Model (2), BT_DIFFi,t, by DA_NONCONi,t, and exclude the independent variable BT_DIFFi,avg from the model. DA_NONCONi,t captures the non-conforming part of the discretionary accruals and is measured by a firm's discretionary accruals (DAi,t) minus the conforming portion of discretionary accruals (DA_CONi,t). DAi,t is the discretionary accruals obtained from the modified Jones model. Although not tabulated, the results of this sensitivity test are qualitatively similar to the results obtained from the original Model (2). TAXINi,t is negatively associated with DA_NONCONi,t at the 1 per cent level, while TAXDEi,t is not significantly correlated with DA_NONCONi,t. This result further supports our findings that firms use book-tax non-conforming tax management before a tax rate increase.

Third, we extend our data to include 2007 firm-year observations.19 Although China's accounting standards changed significantly in 2007, we find similar results to those tabulated in this paper. TAXINi,t is negatively associated with BT_DIFFi,t at the 1 per cent level. Fourth, we use a continuous variable, TAXIN_CONTi,t (measuring the magnitude of a tax rate increase), to replace TAXINi,t. Results from this sensitivity test are qualitatively similar to the original results. We find that TAXIN_CONTi,t is not significant in Model (1) and is negatively significant at the 1 per cent level in Model (2), whereas the interaction term of SOEi,t and TAXIN_CONTi,t is negatively significant at the 10 per cent level in Model (4).

Fifth, to test whether tax rate changes are endogenous and affect our main results, we run a two-stage analysis for Model (1) and Model (2), respectively. We estimate TAXINi,t and TAXDEi,t by including firm characteristic variables (i.e., SIZEi,t, DEBTi,t, and BMi,t), as defined in the main regression, and exogenous variables that may affect tax rate changes of a company. The exogenous variables include AGE (measures a firm's listing age), INCORP (measures a firm's length of incorporation), TAX (measure a firm's current year tax rate), and LOCATION (a vector of location dummy variables). We rerun Model (1) and Model (2) by including the inverse Mill's ratios for TAXINi,t and TAXDEi,t. Results of this sensitivity test are similar to the original results reported. We find that TAXINi,t is negatively associated with book-tax differences at the 1 per cent level, while TAXDEi,t is negatively and significantly correlated with conforming discretionary accruals at the 5 per cent level. The inverse Mill's ratios are not statistically significant.

Finally, as BOOK_MANi,t reflects book management for two different motivations, we break down BOOK_MANi,t into two dummy variables, LOSSi,t and NEWi,t (Lo et al., 2010). LOSSi,t is equal to 1 if a firm's ROE is between 0 and 1.5 per cent (i.e., just above the delisting earnings threshold), and 0 otherwise. NEWi,t is equal to 1 if a firm's ROE is between 6 and 7.5 per cent, or between 10 and 11.5 per cent (i.e., just above the earnings thresholds for issuing new shares), or if a firm issues new shares in the following year; it is 0 otherwise. Breaking down BOOK_MANi,t into LOSSi,t and NEWi,t does not materially affect our main results, and we find that TAXDEi,t is still negatively associated with DA_CONi,t in Model (1), while TAXINi,t is still negatively significant in Model (2). TAXINi,t is not correlated with DA_CONi,t, and TAXDEi,t is not correlated with BT_DIFFi,t. Both LOSSi,t and NEWi,t are positively associated with BT_DIFFi,t at the 1 per cent level. In summary, our main regression findings are robust after controlling for several alternative measures of the dependent and independent variables.

6 Conclusions

Companies in China are subject to different tax rates during different time periods. By shifting their taxable profits from high tax rate periods to low tax rate periods, companies can reduce their overall tax liabilities. In addition, SOEs have stronger tunneling incentives and weaker book management incentives than do NSOEs. This institutional environment creates an excellent setting for us to investigate how the associations between various tax, financial reporting, and tunneling incentives affect the opportunistic behavior of managements in corporate reporting.

Our empirical findings demonstrate that firms choose different tax management methods in response to tax rate increments as compared to those in response to tax rate reductions. In particular, firms that anticipate tax rate reductions are more likely to manage their taxable income downward through book-tax conforming discretionary accruals. By contrast, we hypothesize and find that firms that anticipate tax rate increases are more likely to manage their taxable income upward through book-tax differences. These results also suggest that firms give more weight to tax incentives and tax audit or regulatory inspections risks than to boosting financial reporting income in tax management. In particular, firms are willing to incur higher financial reporting costs by choosing a method that can reduce tax liabilities and the risk of qualified audit reports arising from aggressive book reporting. In addition, we find that firm characteristics that capture book management and tunneling incentives have significant impacts on tax management strategies. Specifically, NSOEs that have higher book management incentives than SOEs would manage taxable income upward book-tax conformingly before a tax rate increase where SOEs would not.

Taken together, these findings contribute to the existing literature by giving new evidence on upward tax management. Our study shows that book-tax conforming discretionary accruals and book-tax differences reflect different tax planning activities. This enhances our understanding of how managers may engage in tax-induced opportunistic reporting behavior under different financial reporting and tunneling incentives. The interpretation of earnings quality or tax planning activities is fraught with difficulty if the tax and financial reporting incentives are not properly controlled for.