Are Related-Party Sales Value-Adding or Value-Destroying? Evidence from China

We are especially grateful to the editor (Sidney Gray) and the anonymous referee for their insightful and constructive suggestions. We also thank Michael Firth, Clive Lennox, and seminar participants at the 36th EAA Annual Congress at Paris for their helpful comments, discussions, and suggestions on earlier drafts of the paper. This research has benefited from financial support from the Lingnan University, Hong Kong. Raymond Wong (corresponding author) acknowledges the financial support of a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. CityU 195513). All remaining errors and omissions are our own.

Abstract

Prior literature provides mixed and relatively little evidence on the economic consequences of related-party transactions. We examine a hitherto underexplored issue of whether transactions among firms within the same business group increase or reduce firm value. Using a large sample of Chinese listed firms, we find that related-party sales increase firm value. However, this value enhancement disappears for firms with (i) large percentage of parent directors, (ii) high government ownership, or (iii) tax avoidance incentives that often couple with management's rent extraction activities. Although we find that intragroup sales improve firm value in general, we also find that corporate insiders use intragroup sales to deprive value from minority shareholders. Overall, our findings highlight the interplay between ownership structure and tax avoidance incentives in determining the economic consequences of related-party transactions.

1 Introduction

A number of well-publicized accounting scandals around the world, such as the Enron failure (USA), the Pfizer Laboratories case (Pakistan), the BAT-Yava case (Russia), and the Greencool case (China), reveal that firms engage in related-party transactions (RPTs) to opportunistically manage earnings for financial reporting purposes or to tunnel profits to their controlling shareholders at the expense of minority shareholders. Stated another way, this anecdotal evidence suggests that RPTs are used as a means for controlling shareholders and management to extract private control benefits at the expense of outside minority shareholders. Conversely, the fact that laws do not prohibit RPTs suggests that RPTs are normal business practices in that within-group transactions serve as a common means for normal business operations and resource allocation among affiliated firms within the same business group. While large business groups play an important role in emerging economies in Asia, as well as in many Western European countries, prior research has paid relatively little attention to the economic consequences of within-group business transactions or RPTs and in particular, their impacts on firm performance or the market value of the firm. As a result, the question of whether and how RPTs affect firm valuation remains contentious and unresolved.

Related-party transactions can be value-destroying if they are used as a means for managerial opportunism, such as opportunistic earnings management, and tunneling and expropriation of wealth from shareholders. More specifically, under certain conditions RPTs can allow controlling owners and corporate executives of a listed company to earn private control benefits: RPTs can be used as a means to expropriate corporate wealth from outside minority shareholders to controlling shareholders and corporate executives (OECD, 2009). For example, shifting profits from listed companies to non-listed parent companies or non-listed privately owned companies may result in decreased profit attributable to the outside shareholders of listed companies. Jian and Wong (2010) find that Chinese firms prop up their related-party sales to meet earnings targets as stipulated by the regulators,1 and simultaneously to divert profits to their controlling owners. Kim and Yi (2006) show that Korean firms affiliated with a large business group provide controlling shareholders with more incentives and opportunities for opportunistic earnings management than independent firms. Their finding suggests that intragroup transactions are used as a means for opportunistic earnings management, particularly for the benefit of controlling shareholders. Other studies have also shown that corporate insiders can make use of related-party sales as a mechanism to manipulate profit statements for maximizing their compensation or to obfuscate their manipulative practices (Lo et al., 2010a; Kim et al., 2011).

Although prior accounting scandals and literature suggest that RPTs are used for opportunistic earnings management and tunneling, RPTs are a natural part of business as well. In fact, firms can exhibit a high volume of such transactions even when they do not engage in opportunistic earnings management and/or accounting and financial fraud (Gordon et al., 2007). Djankov et al. (2008) point out the fact that no country completely prohibits RPTs: This suggests that at the country level, the benefits from allowing RPTs are likely to be greater than the associated costs and that at the firm level, RPTs could enhance firm's operating efficiency. For example, some companies can benefit from RPTs by making strategic investments in joint ventures such that they can obtain and secure access to supplies or markets and to reduce their business risk (Kohlbeck and Mayhew, 2010).

Despite the conflicting arguments on the purposes of RPTs, there is little direct evidence on the impacts of RPTs on firms’ value (Ryngaert and Thomas, 2012). Even though some studies examine the economic consequences of RPTs, their findings are mixed. For example, Kohlbeck and Mayhew (2010) find that investors respond negatively to the disclosure of related-party loans and guarantees one year before the enforcement of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. In a related vein, Cheung et al. (2006) find that minority shareholders of Hong Kong listed firms experience large value losses at the announcement of connected transactions during 1998–2000. These two studies suggest that investors react negatively on the disclosure of RPTs. However, Buysschaert et al. (2004) find that market reacts positively to the announcement of intragroup equity sales in Belgian companies. Using an Indian sample of listed firms, Khanna and Palepu (2000) find that firms affiliated with a corporate group perform better than non-affiliated companies, suggesting that corporate group affiliation is associated with better resource allocation among affiliated firms. Although Khanna and Palepu's (2000) study does not address the impacts of RPTs directly, their results are consistent with the argument that internal transactions within the same business group help group-affiliated companies improve their performance, because of the greater trust established and the lower information asymmetry achieved through transactions with related-parties than those with non-affiliated companies.

Although we cannot directly compare the above results as these studies investigate different types of RPTs in different countries, the inconclusive evidence is not surprising given the complicated nature of RPTs and possible contradictory impacts of different types of RPTs on firm value. Therefore, our study aims to provide an in-depth analysis on whether related-party sales transactions enhance or reduce the market value of the firm. We examine our research issues using a sample of Chinese listed firms, because China's institutional environment provides us with a unique and rich setting. In China, RPTs are very prevalent, where the sale of goods and services among related parties is the most commonly conducted transactions by the Chinese listed companies. Historically, China's state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have often relied on internal product markets for their product sales or input supplies (e.g., materials and labor) and on internal capital markets for financing, in particular, prior to initial public offerings (IPOs). Before going public, these SOEs, typically production units or factories under direct control of the central or local governments, are carved out and undergo the corporatization process by issuing shares. After carve-outs and corporatization, certain corporatized units (which meet the listing requirements) are listed on the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges via IPOs. In the post-IPO period, these listed subsidiaries tend to engage frequently in RPTs with their parent SOEs and other subsidiaries that are controlled by the same SOEs (Jian and Wong, 2010; Lo et al., 2010b). As Jian and Wong (2010) report, more than 50 per cent of Chinese listed firms are involved in related-party sales to some extent. The sales of goods and services are recurring activities, where the manipulation via sales of goods and services is less likely to be detected. We believe that the considerable volume of RPTs in China and its manipulative nature increase the power of our tests of examining the economic consequences of RPTs. Our first objective is thus to investigate whether related-party sales transactions2 by Chinese listed companies are value-adding or value-destroying.

The second objective of this study is to investigate whether and how the influence or power of controlling shareholders affects the value of RPTs. The control power of controlling shareholders and management is an important factor affecting the decisions on RPTs in China. As mentioned previously, many Chinese listed companies are originally spun off from unlisted parent companies prior to their own listing. As a result, their parent SOEs remain as important controlling shareholders, retain significant control via high voting rights, and exercise a significant influence over their listed subsidiaries even after IPOs (Ding et al., 2007; Berkman et al., 2010; Lo and Wong, 2011). For example, Gul et al. (2010) report that during their sample period of 1996–2003, the largest shareholder in Chinese listed firms holds about 32 per cent of shares outstanding, and about 67 per cent of the largest shareholders are the government. It is also common that parent SOEs often dispatch directors to listed subsidiaries to exercise their control rights. Highly concentrated ownership with the controlling shareholders (usually the government), along with significant influence of the “parent directors” (i.e., directors who are representatives of the parent companies of the listed firms), increases incentives and opportunities for tunneling or income shifting via related-party sales in China (Lo et al., 2010a,b). Such tunneling helps the controlling shareholders camouflage their extraction of private control benefits from outside minority shareholders, which usually brings about losses to the latter shareholders (Liu and Lu, 2007). Although the influence or power of controlling shareholders in affecting the decision on RPTs is documented in prior literature, evidence is scarce about its moderating impacts on the relation between RPTs and firm value. Therefore, our analyses focus on whether the impact of related-party sales on firm valuation differs systematically for firms with high government ownership compared to those with low government ownership, and for firms with a large percentage of parent directors on the board compared to those with a small percentage.

Finally, we also investigate how taxes affect the association between RPTs and firm value. Prior research shows that group companies make use of intragroup transactions to achieve tax savings based on the tax rate differentials between jurisdictions or within a jurisdiction (Harris, 1993; Cravens and Shearon, 1996; Jacob, 1996; Oyelere and Emmanuel, 1998; Conover and Nichols, 2000; Gramlich et al., 2004; Lo et al., 2010b). Tax planning opportunities also exist for companies that are subject to tax rate changes across time (Guenther, 1994; Lo et al., 2010c). For example, firms can shift profits out from a year with a tax rate increase for tax savings. Despite the tax savings, this tax planning activity can also be used as an excuse for management to tunnel profits out from the listed company to its parent company or other related company.3 By the same token, firms can shift profits into a year with a tax rate reduction for tax savings, but they can also use tax planning as a means to prop up income to hide bad news. A number of recent studies argue and find that firm value is negatively affected by corporate tax avoidance and planning activities. This is because tax avoidance and planning activities are usually coupled with managerial rent extraction activities, such as earnings management and related-party transactions, because the latter activities provide tools, masks, excuses, and justifications for the former activities or vice versa (Desai and Dharmapala, 2006, 2009; Desai et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011). To provide empirical evidence on the role of taxes in determining the effect of RPTs on firm value, our analyses focus on whether related-party sales transactions have different impacts on firm valuation when tax rates change.

Using a sample of 4,520 Chinese listed firms during the period of 2002–2009, we find that the value of the firm4 is positively associated with the abnormal level of related-party sales transactions (i.e., the intragroup sales above and beyond the normal level),5 but the association is less pronounced for firms with large percentage of parent directors and those with high government ownership. The findings are robust to controlling for various firm characteristics (namely size, firm age, tax rate, leverage, liquidity, growth, and profitability) as well as the firm and year fixed effects.

Put differently, our results support the view that RPTs are generally used as a tool for improving resource allocation efficiency among affiliated firms within the same business group, thereby increasing firm value. However, in an environment where controlling shareholders and/or parent companies are able to exercise a significant influence over minority shareholders and/or listed subsidiaries, RPTs are likely to serve as a means to divert corporate resources from the latter to the former. In this environment, RPTs are thus likely to be value-destroying rather than value-adding. More specifically, our results are in line with the view that firms with a large percentage of parent directors and high government ownership are more likely to tunnel profits out to prop up their related (low-profit or loss-making) companies via related-party sales transactions. Because of this tunneling activity, a negative impact of RPTs on the market value of the tunneled company offsets or exceeds the associated positive effect mentioned above.

For the effect of corporate tax avoidance incentives, we find that the positive association between abnormal related-party sales and firm value becomes weakened for firms that are subject to a tax rate increase or a tax rate decrease. These results suggest that the value-destroying effect of RPTs associated with non-tax incentives (e.g., managing earnings upward to hide bad news or tunneling profits out for the benefits of controlling shareholders) appears to outweigh the value-adding effect of RPTs associated with tax-saving incentives. Therefore, although firms with abnormally high related-party sales transactions are associated with higher firm value in general, the firm value enhancement associated with RPTs tends to be reduced by corporate tax avoidance and planning activities because these activities facilitate managerial opportunistic rent extraction.

Our study contributes to existing research in several ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine whether and how the value of RPTs is influenced by the largest controlling shareholder of unlisted parent company (or the government) via parent directors’ participation and through concentrated ownership with the largest shareholder—typically the government. Second, our study provides evidence that helps explain and reconcile reasons why prior research documents mixed, albeit limited, evidence about the valuation effect of RPTs.6 We provide new evidence that the positive impact of related-party sales transactions on firm value is mitigated by the influence of the largest shareholder. This influence is typically exercised via the concentrated ownership with the largest controlling shareholder of unlisted parent company or the appointment of parent directors to listed subsidiaries. Finally, we provide existing and potential investors with new insights into the unintended impact of corporate tax planning on the valuation of related-party sales transactions. Stated another way, our study helps us better understand the tax and non-tax factors that influence the decision to make internal resources allocations via RPTs.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the sample, research design and explains how controlling shareholders and tax planning activities might affect the association between related-party sales and firm value; Section 2.1 discusses the results; Section 2.2 provides further tests on the association between abnormal returns and related-party sales transactions and discusses sensitivity tests; and Section 2.3 concludes the paper.

2 Data and Research Design

Our initial sample is comprised of all of the companies that are listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange during 2002–2009, excluding financial institutions and utilities companies. We also exclude those firms with missing data for any year in the sample period. Related-party sales and ownership data are collected from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) related-party transaction database. We hand-collect data on the statutory tax rate7 and the ultimate shareholders of the listed companies as it applies to each firm in our sample.8 All other financial data are extracted from the CSMAR general research database. The final sample that meets all our criteria consists of 4,520 firm-year observations (565 firms).

2.1 Firm Value and Related-Party Sales

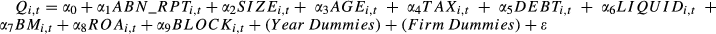

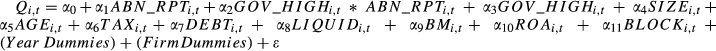

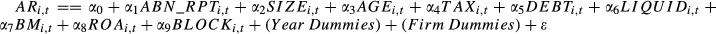

As mentioned previously, prior studies show inconclusive evidence about the impact of RPTs on firm valuation or the market value of the firm. To test whether related-party sales have positive or negative impacts on firm value, we estimate the following regression:

(1)

(1)In the above, the dependent variable, Qi,t, represents industry-adjusted Tobin's Q and is measured by the ratio of the market value of assets divided by the book value of total assets minus the industry average ratio. Following previous research (Berkman et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2009; Kim and Lu, 2011), we measure the market value of assets by the market value of common equity plus the book value of total liabilities minus balance sheet deferred tax assets. The test variable, ABN_RPTi,t, represents the abnormal portion of a firm's related-party sales transactions. We define related-party sales transactions as the sales of goods and services among related companies. Cheung et al. (2006) and Berkman et al. (2010) suggest that companies carry out different related-party activities to expropriate resources from minority shareholders that include purchase or sale of assets, purchase or sale of goods and services, sale of equity, and cash payment to related companies. Among these related-party activities, the sale of goods and services is the most commonly conducted transactions by the Chinese listed companies. Unlike the sales of fixed assets or equity, the sales of goods and services are recurring activities, where the manipulation via sales of goods and services is less likely to be detected (Jian and Wong, 2010). Following prior studies (Jian and Wong, 2010; Lo et al., 2010a), our analyses focus on related-party sales transactions in China rather than other types of RPTs.

Given the nature of business and industry structures, a firm can engage in related-party sales transactions as part of its normal business operations. In such a case, firm management does not have discretion over the volume of related-party sales. However, related-party sales can also be discretionary or abnormal. The magnitude of a firm's involvement in abnormal related-party sales is influenced by a variety of factors, including the extent of a firm's tax avoidance and planning activities, the demand for internal resources allocation among affiliated firms or subsidiaries, earnings management incentives, and profit expropriation activities. Similar to Jian and Wong (2010), we decompose total related-party sales into normal and abnormal parts. For this purpose, for each sample year, we regress RPTi,t (measured by a firm's related-party sales, scaled by the total assets) against SIZEi,t (measured by the natural log of total assets), DEBTi,t (measured by the total debt-to-asset ratio), BMi,t (measured by the ratio of book value to market value of equity), and industry fixed effects. We measure abnormal related-party sales (ABN_RPTi,t) using the residual of the above regression.9

In equation 1, we include several control variables that are known to affect Tobin's Q. Following prior studies (Gompers et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2009), we include SIZEi,t (as defined earlier) and AGEi,t (as measured by the natural log of a firm's age since listing).10 As firms in China are subject to different statutory tax rates based on the preferential tax policies they are entitled to,11 we include a firm's statutory tax rate, TAXi,t, as one of the control variables. Firms that are subject to a lower tax rate are likely to have higher levels of cash flow, and thus higher firm value, all else being equal. Also, previous research shows that leverage, liquidity, growth, and profitability will affect firm value (Chang and Hong, 2000; Doidge et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2004). As such, we include DEBTi,t (as defined earlier), LIQUIDi,t (measured by the current-to-total debt ratio), BMi,t (as defined earlier), and ROAi,t (measured by the return on assets ratio) as additional controls. We also include BLOCKi,t (measured by the sum of percentage of shareholdings of the second to the tenth largest shareholders) as one of the control variables (Berkman et al., 2009). Finally, we include Year Dummies and Firm Dummies to control for year and firm fixed effects.

2.2 Influence of Controlling Shareholders

As mentioned earlier, controlling shareholders can have significant impacts on the sensitivity of firm value to RPTs. In China, many listed companies are spin-offs of the profitable units of SOEs since the economic reform of the 1990s (Green, 2003; Chow, 2007). After the spin-offs, SOEs retain the unprofitable units of the business as well as the social activities (e.g., hospitals, schools, etc.), whereas the profitable units are listed on the stock exchanges. The unlisted parent SOE requires resources from the listed firms so that the poor-performing divisions and non-revenue generating units of the SOE can survive (Wu, 2005; Ding et al., 2007). These unlisted parents are likely to appoint some of their own executives as the directors of their newly listed subsidiary so that they can exercise influence on the corporate decisions such as the decisions on RPTs (Lo et al., 2010a). In most cases, these so-called parent directors are not paid directly by the listed companies, but are instead paid by the unlisted parent companies. As such, parent directors may take instructions from, and act for the benefit of, the parent company at the expense of the minority shareholders of the listed companies. For example, Lo et al. (2010a) find that firms with a high percentage of parent directors are more likely to shift profits from the listed companies to their parent companies via related-party sales transactions than are firms with a low percentage of parent directors.

Another way to maintain substantial influence over the listed spin-off firm is via a significant ownership by the unlisted SOE (Ding et al., 2007). Indeed, many of Chinese listed companies are still owned by the original unlisted parent SOEs (Wu, 2005; Walter and Howie, 2006). This ownership structure unique to China exerts a significant influence over management's business decisions (Wang et al., 2008; Jian and Wong, 2010). Lo et al. (2010b) find that the higher the percentage of shares owned by the parent SOEs, the higher the transfer pricing manipulation for shifting profits out from the listed companies. Apart from the parent director's appointment, we therefore expect that the percentage of shares owned by the parent companies should have significant impacts on the association between firm value and related-party sales transactions. On the other hand, despite the negative influences caused by the controlling owners, controlling shareholders such as unlisted parent companies or the government may have superior information and better knowledge of the parent company and its subsidiaries. As such, the ownership concentration with controlling shareholders and/or the presence of parent directors may indeed help the listed affiliated companies improve the monitoring efficiency as well as the internal resource allocation efficiency in relation to related-party sales transactions. Given the above conflicting arguments, the directional effect of the concentrated ownership and parent directorship on the value of related-party sales transactions is an empirical question. This study therefore aims to provide empirical evidence on this interesting, but under-researched, issue.

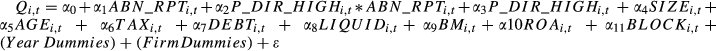

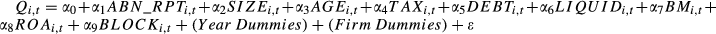

(2)

(2) (3)

(3)In equation 2, P_DIR_HIGHi,t is equal to 1 if the percentage of parent directors of a firm is higher than the median in all the years during the sample period, and 0 otherwise. In equation 3, GOV_HIGHi,t is equal to 1 if the percentage of government ownership of a firm is higher than the median in all the years during the sample period and 0 otherwise. The main variables of interests in the two regressions are the interaction terms of P_DIR_HIGHi,t*ABN_RPTi,t and GOV_HIGHi,t *ABN_RPTi,t where any significant coefficient represents the moderating impacts of controlling shareholders’ influences on the association between related-party sales and firm value. Besides, to further verify the influence of controlling shareholders on the value of RPTs, we partition our sample firms into (i) firms with a large percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_HIGHi,t) versus firms with a small percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_LOWi,t) and (ii) firms with high government ownership (GOV_HIGHi,t) versus firms with low government ownership (GOV_LOWi,t).12 In so doing, we classify a firm as having a large (small) percentage of parent directors if its percentage of parent directors was above (below) the median in all the years during the sample period. Similarly, we classify a firm as having high (low) government ownership if its government ownership is above (below) the median in all the years during the sample period.13 We then re-estimate equation 1 for each partitioned subsample.

2.3 Influence of Corporate Tax Avoidance Incentives

Corporate tax rate is another important factor that influences corporate strategy in general and tax planning policy in particular, as it directly affects a firm's cash flow and thus firm value. Therefore, we investigate whether and how the impact of related-party sales transactions on firm value is differentially affected by corporate tax planning activities driven by tax rate changes. Prior studies find that the major objective of corporate tax avoidance and planning policies can be achieved by related-party sales transactions (e.g., Lo et al., 2010b). Besides, corporate groups can reduce their overall tax liabilities by shifting profits from a period paying high tax rates to a period paying low tax rates (Guenther, 1994; Lo et al., 2010c).

In China, the government offers listed firms various forms of tax incentives and tax reductions, and these incentives vary across location, industry, and form of investment. Therefore, Chinese listed firms face tax rate changes when their preferential tax policies expire or when they are entitled to new tax concession policies. Some Chinese listed firms also encounter a tax rate change in 2008 owing to the introduction of the 2008 Enterprise Income Tax Law.14 Firms can take advantage of the tax rate change for tax savings by shifting profits into the period with a tax rate reduction or shifting profits out from the period with a tax rate increase. On the one hand, these tax-minimizing activities should normally help listed affiliates improve their cash flow performance and thus firm value. On the other hand, one may also expect that corporate managers can take advantage of the tax rate changes for their own private benefits by excessively engaging in tax avoidance and planning activities. For example, Desai et al. (2007) suggest that a higher tax rate increases the return to “theft” by insiders. Desai and Dharmapala (2009) find that the (positive) value of tax planning activities will be offset by increased opportunities for rent diversion provided by tax shelters. Kim et al. (2011) find that corporate tax avoidance is positively associated with firm-specific stock price crash risk and suggest that tax avoidance creates managerial incentives to camouflage unfavorable information about a firm's future prospect. As such, firms may use related-party sales transactions as a means to cover up rent diversion facilitated by the aggressive tax avoidance and planning policy.

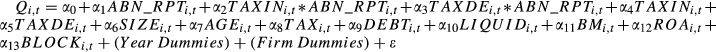

(4)

(4)In equation 4, TAXINi,t is an indicator variable that is equal to 1 if the tax rate in the current year is higher than the tax rate in the previous year, and 0 otherwise. TAXDEi,t is an indicator variable that is equal to 1 if the tax rate in the current year is smaller than the tax rate in the previous year, and 0 otherwise. Any significant coefficient on the interaction terms of TAXINi,t*ABN_RPTi,t and TAXDEi,t*ABN_RPTi,t signifies the influences of corporate tax avoidance incentives on the association between related-party sales and firm value. Further, we also examine the importance of tax rate changes on the value of RPTs by partitioning our sample firms into (i) firms with a tax rate increase (TAXINi,t), (ii) firms with a tax rate decrease (TAXDEi,t), and (iii) firms with no tax rate change. We then re-estimate equation 1 for each partitioned subsample. Table 1 summarizes the definitions of all the variables used in our empirical tests.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Qi,t | Industry-adjusted Tobin's Q. Tobin's Q is measured by market value of assets divided by the book value of total assets. Market value of assets is measured by market value of common equity plus the book value of total liabilities minus balance sheet deferred tax assets. |

| RPTi,t | Related-party sales of the firm, scaled by total assets. |

| ABN_RPTi,t | Abnormal related-party transactions of the firm. We follow Jian and Wong's (2010) model to regress, year-to-year, RPT (measured by a firm's related-party sales, scaled by the total assets) against SIZE (measured by the natural log of total assets), DEBT (measured by the total debt-to-asset ratio), BM (measured by the book-to-market equity ratio), and industry fixed effects. The residual term of the regression model refers to abnormal related-party sales transactions. |

| SIZEi,t | Natural log of total assets of the firm. |

| AGEi,t | Natural log of the firm's age since listing. |

| TAXi,t | Statutory tax rate of the firm. |

| DEBTi,t | Total debt over total assets of the firm. |

| LIQUIDi,t | Current liabilities over total liabilities of the firm. |

| BMi,t | Book-to-market equity ratio of the firm. |

| ROAi,t | Return on assets of the firm. |

| BLOCKi,t | Sum of the percentage of shareholdings of the second to the tenth largest shareholders. |

| P_DIR_HIGHi,t | Equal to 1 if the percentage of parent directors of a firm is higher than the median in all the years during the whole sample period; 0 otherwise. |

| P_DIR_LOWi,t | Equal to 1 if the percentage of parent directors of a firm is lower than the median in all the years during the whole sample period; 0 otherwise. |

| GOV_HIGHi,t | Equal to 1 if the percentage of government ownership of a firm is higher than the median in all the years during the whole sample period; 0 otherwise. |

| GOV_LOWi,t | Equal to 1 if the percentage of government ownership of a firm is lower than the median in all the years during the whole sample period; 0 otherwise. |

| TAXINi,t | A dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the tax rate in the current year is higher than the tax rate in the previous year; and 0 otherwise. |

| TAXDEi,t | A dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the tax rate in the current year is lower than the tax rate in the previous year; and 0 otherwise. |

| ARi,t | Size-adjusted abnormal return, measured from the beginning of the fourth month of the current year to the end of the third month of the following year. |

3 Empirical Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for our total sample of 4,520 observations over the period of 2002–2009. As shown in Table 2, industry-adjusted Tobin's Q, denoted by Qi,t, has the mean (median) of 0.150 (−0.140) with its standard deviation of 1.426, suggesting that its distribution is skewed. The test variable, ABN_RPTi,t, has the mean (median) of 0.003 (−0.027) with its standard deviation of 0.155. The mean P_DIR_HIGHi,t of 0.209 indicates that about 21 per cent of firms have more parent directors than the sample median in all years during the sample period, while the mean GOV_HIGHi,t of 0.368 indicates that nearly 37 per cent of firms have government ownership that is higher than the sample median in all sample years. The mean and median of SIZEi,t are 21.476 and 21.362 with its standard deviation of 1.118, suggesting that while the distribution appears to be approximately normal, its variation is relatively narrow, reflecting the fact that listed firms in China consist of relatively large firms during the sample period. The mean of AGEi,t is 2.105, which implies that the average listing age of firms is around 8.2 years, reflecting a short history of China's stock markets. The mean and median of statutory tax rate for firms (TAXi,t) are 22.9 and 25 per cent, respectively. The mean and median of DEBTi,t are 0.521 and 0.517, respectively, suggesting that more than half of the total assets of the listed companies are financed by debt. The liquidity (LIQUIDi,t) of the sample firms is quite high with the mean and median of 0.845 and 0.918, respectively. Lastly, the mean of book-to-market equity ratio (BMi,t), return on assets (ROAi,t), and block ownership (BLOCKi,t) are 0.485, 0.021, and 0.173, respectively.

| Variable | Mean | Std. D | 5% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qi,t | 0.150 | 1.426 | −1.120 | −0.480 | −0.140 | 0.410 | 2.230 |

| RPTi,t | 0.046 | 0.139 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.240 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.003 | 0.155 | −0.084 | −0.055 | −0.027 | 0.004 | 0.180 |

| SIZEi,t | 21.476 | 1.118 | 19.931 | 20.741 | 21.362 | 22.074 | 23.411 |

| AGEi,t | 2.015 | 0.553 | 0.693 | 1.792 | 2.079 | 2.398 | 2.708 |

| TAXi,t | 0.229 | 0.088 | 0.150 | 0.150 | 0.250 | 0.330 | 0.330 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.521 | 0.226 | 0.198 | 0.379 | 0.517 | 0.644 | 0.837 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.845 | 0.189 | 0.430 | 0.773 | 0.918 | 0.988 | 1.000 |

| BMi,t | 0.485 | 0.350 | 0.095 | 0.256 | 0.423 | 0.646 | 1.086 |

| ROAi,t | 0.021 | 0.084 | −0.099 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.051 | 0.107 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.173 | 0.130 | 0.016 | 0.061 | 0.145 | 0.269 | 0.415 |

| P_DIR_HIGHi,t | 0.209 | 0.407 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| P_DIR_LOWi,t | 0.177 | 0.382 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| GOV_HIGHi,t | 0.368 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| GOV_LOWi,t | 0.343 | 0.475 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

- This table presents firms characteristics for our sample of 4,520 firm-year observations from 2002 to 2009. Our sample comprises all companies that are listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange during 2002–2009, excluding financial institutions and utilities companies. We also exclude those firms with missing data for any year in the sample period. Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1.

3.2 Firm Value, Related-Party Sales, and Controlling Shareholders’ Influence

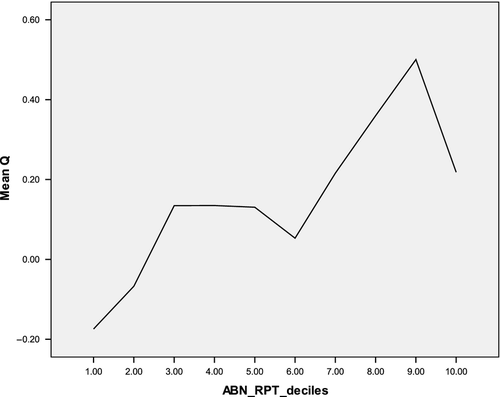

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall value of the firm, captured by industry-adjusted Tobin's Q, increases with a firm's involvement in abnormal related-party sales transactions. For the entire sample period, we first sort firms annually into ten deciles based on their abnormal related-party sales (ABN_RPTi,t) and then compute industry-adjusted Tobin's Q (Qi,t) for firms that belong to each decile. As depicted in the figure, firm value is, overall, positively related to the extent of a firm's involvement in related-party sales: Although only suggestive of the underlying relation between the two, Figure 1 clearly illustrates an overall trend that firm value increases with the level of abnormal related-party sales transactions.

- This figure examines the relation between industry-adjusted Tobin's Q and the abnormal related-party sales. We sort firms annually into ten deciles based on their abnormal related-party sales (ABN_RPT) and then compute industry-adjusted Tobin's Q (Q) for firms that belong to each decile.

Table 3 reports the results of regression in equation 1 for the sample (n = 4,520). The results are based on standard errors corrected for firm-level clustering. As shown in the table, the coefficient on our variable of interest, ABN_RPTi,t, is positively significant (t = 2.914). The control variables, SIZEi,t and BMi,t, are negative and significant at the 1 per cent level, whereas AGEi,t and BLOCKi,t are positively significant at the 1 per cent level. In short, the results reported in Table 3 clearly indicate that firms with higher abnormal related-party sales are associated with higher firm value, all else being equal. This finding is in line with the view that related-party sales transactions are used as a tool for improving intragroup resource allocation efficiency rather than as a tool for rent-seeking activities. As a result, on average, firm values increase with related-party sales transactions.

| Whole sample (n = 4,520) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-statistic |

| Intercept | 8.544 | 13.984*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.605 | 2.914*** |

| SIZEi,t | −0.332 | −10.841*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.075 | 2.429*** |

| TAXi,t | 0.288 | 1.502 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.081 | −0.531 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.022 | 0.264 |

| BMi,t | −1.439 | −12.732*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.656 | 0.659 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.005 | 2.779*** |

| YEAR | Included | |

| FIRM | Included | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.291*** | |

- This table examines whether abnormal related-party sales have positive or negative impacts on firm value. The regression equation is as follows:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *** indicates significance at the 1% level (two-tailed test). The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics on our research variables included in our regression models. In Panel A, we partition our total sample into two subsamples with large and small percentages of parent directors based on the median percentage. It shows that ABN_RPTi,t has the mean (median) value of 0.024 (−0.019) for firms with large percentage of parent directors (i.e., P_DIR_HIGHi,t = 1), whereas ABN_RPTi,t has the mean (median) value of −0.015 (−0.039) for firms with small percentage of parent directors (i.e., P_DIR_LOWi,t = 1). In Panel B, we partition our total sample into two subsamples with high and low government ownership based on its sample median. We find that ABN_RPTi,t has the mean (median) value of 0.020 (−0.025) for firms with high government ownership (i.e., GOV_HIGHi,t = 1), whereas ABN_RPTi,t has the mean (median) value of −0.013 (−0.031) for firms with low government ownership (i.e., GOV_LOWi,t = 1). Briefly, our results show that firms with higher influence of controlling shareholders (i.e., large percentage of parent directors and high government ownership) engage in more abnormal RPTs than firms with lower influence of controlling shareholders. This finding is broadly consistent with prior China studies that show that firms with higher government ownership (in which the government is the largest controlling shareholder) engage in more RPTs (Cheung et al., 2009; Jian and Wong, 2010).

| Panel A: Large versus small percentage of parent directors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Large percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_HIGH; n = 944) | Small percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_LOW; n = 800) | ||||

| Mean | Median | Std. D | Mean | Median | Std. D | |

| Qi,t | 0.196 | −0.110 | 1.392 | 0.014 | −0.170 | 1.006 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.024 | −0.019 | 0.219 | −0.015 | −0.039 | 0.109 |

| SIZEi,t | 21.501 | 21.393 | 1.147 | 21.553 | 21.406 | 1.034 |

| AGEi,t | 2.091 | 2.197 | 0.526 | 1.961 | 2.079 | 0.561 |

| TAXi,t | 0.224 | 0.240 | 0.086 | 0.232 | 0.250 | 0.090 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.499 | 0.495 | 0.226 | 0.496 | 0.500 | 0.177 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.836 | 0.920 | 0.196 | 0.849 | 0.903 | 0.169 |

| BMi,t | 0.487 | 0.416 | 0.394 | 0.520 | 0.457 | 0.320 |

| ROAi,t | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.085 | 0.029 | 0.032 | 0.063 |

| BLOCKi,t | 18.074 | 15.730 | 12.978 | 15.198 | 11.555 | 12.340 |

| Panel B: High vs. low government ownership | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | High government ownership (GOV_HIGH; n = 1,664) | Low government ownership (GOV_LOW; n = 1,552) | ||||

| Mean | Median | Std. D | Mean | Median | Std. D | |

| Qi,t | 0.069 | −0.141 | 1.154 | 0.184 | −0.129 | 1.535 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.020 | −0.025 | 0.166 | −0.013 | −0.031 | 0.144 |

| SIZEi,t | 21.788 | 21.616 | 1.175 | 21.254 | 21.193 | 1.033 |

| AGEi,t | 1.946 | 2.079 | 0.566 | 2.041 | 2.197 | 0.548 |

| TAXi,t | 0.223 | 0.180 | 0.086 | 0.234 | 0.250 | 0.089 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.479 | 0.485 | 0.185 | 0.537 | 0.521 | 0.233 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.846 | 0.926 | 0.191 | 0.855 | 0.918 | 0.172 |

| BMi,t | 0.496 | 0.443 | 0.284 | 0.467 | 0.405 | 0.329 |

| ROAi,t | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.056 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.102 |

| BLOCKi,t | 10.314 | 7.410 | 9.144 | 23.189 | 22.950 | 12.908 |

- This table presents firms characteristics for four subsamples of firms with P_DIR_HIGH=1 versus P_DIR_LOW=1 (Panel A), and with GOV_HIGH=1 versus GOV_LOW=1 (Panel B). Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1.

Panels A and B of Table 5 report the regression results of equations 2 and 3, respectively. We find that ABN_RPTi,t is positively significant at the 1 per cent level in both Panels A and B, and the interaction terms, P_DIR_HIGHi,t*ABN_RPTi,t (Panel A) and GOV_HIGHi,t*ABN_RPTi,t (Panel B), are negatively significant at the 5 and 10 per cent levels, respectively. These results suggest that the positive impact of related-party sales on firm value is weaker for firms with a large percentage of parent directors and a high government ownership. Table 6 reports the regression results for the four partitioned directorship/ownership subsamples. For the subsample of firms with a low percentage of parent directors (i.e., P_DIR_LOWi,t = 1), we find that ABN_RPTi,t is significantly positive at the 5 per cent level (Panel A). We find, however, that for the high-percentage subsample (i.e., P_DIR_HIGHi,t = 1), ABN_RPTi,t is insignificant. For the subsample of firms with low government ownership (i.e., GOV_LOWi,t = 1), ABN_RPTi,t is significantly positive at the 5 per cent level (Panel B). However, for firms with high government ownership (i.e., GOV_HIGHi,t = 1), ABN_RPTi,t is insignificant.

| Whole sample (n = 4,520) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-statistic |

| Panel A: | ||

| Intercept | 8.526 | 14.040*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.935 | 2.925*** |

| P_DIR_HIGHi,t *ABN_RPTi,t | −0.801 | −2.288** |

| P_DIR_HIGHi,t | 0.064 | 1.799* |

| SIZEi,t | −0.332 | −10.871*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.070 | 2.274** |

| TAXi,t | 0.312 | 1.616 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.082 | −0.540 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.032 | 0.390 |

| BMi,t | −1.427 | −12.712*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.686 | 0.695 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.005 | 2.762*** |

| YEAR | Included | |

| FIRM | Included | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.293*** | |

| Panel B: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 8.571 | 13.847*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.837 | 2.464*** |

| GOV_HIGHi,t*ABN_RPTi,t | −0.605 | −1.686* |

| GOV_HIGHi,t | 0.130 | 3.259*** |

| SIZEi,t | −0.340 | −10.808*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.090 | 2.954*** |

| TAXi,t | 0.303 | 1.562 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.071 | −0.467 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.028 | 0.337 |

| BMi,t | −1.410 | −12.333*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.646 | 0.652 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.007 | 3.524*** |

| YEAR | Included | |

| FIRM | Included | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.293*** | |

- This table examines the impacts of controlling shareholders on the association between abnormal related-party sales and firm value.

- The regression equation for Panel A is as follow:

- The regression equation for Panel B is as follow:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively (two-tail test).The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

| Panel A: Large versus small percentage of parent directors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Large percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_HIGH; n = 944) | Small percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_LOW; n = 800) | ||

| Coeff. | t-stat. | Coeff. | t-stat. | |

| Intercept | 9.939 | 8.475*** | 6.340 | 6.998*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.130 | 0.801 | 1.217 | 2.448** |

| SIZEi,t | −0.391 | −7.187*** | −0.223 | −5.356*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.092 | 1.318 | 0.041 | 0.641 |

| TAXi,t | −0.603 | −1.315 | 0.029 | 0.095 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.120 | 0.453 | −0.296 | −0.768 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.069 | 0.420 | 0.070 | 0.516 |

| BMi,t | −1.034 | −6.087*** | −1.546 | −11.939*** |

| ROAi,t | −2.381 | −0.793 | 0.864 | 0.979 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.002 | 0.619 | 0.000 | −0.130 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | ||

| FIRM | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.367*** | 0.454*** | ||

| Panel B: High vs. low government ownership | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | High government ownership (GOV_HIGH; n = 1,664) | Low government ownership (GOV_LOW; n = 1,552) | ||

| Coeff. | t-stat. | Coeff. | t-stat. | |

| Intercept | 4.063 | 6.104*** | 10.362 | 8.954*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.156 | 1.210 | 1.021 | 2.062** |

| SIZEi,t | −0.125 | −4.307*** | −0.411 | −7.692*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.027 | 0.621 | 0.025 | 0.446 |

| TAXi,t | 0.557 | 1.975** | −0.160 | −0.492 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.682 | −5.295*** | 0.250 | 1.061 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.280 | 1.855* | 0.188 | 1.133 |

| BMi,t | −2.073 | −14.534*** | −1.335 | −8.308*** |

| ROAi,t | 5.044 | 4.869*** | −1.366 | −0.977 |

| BLOCKi,t | −0.001 | −0.479 | 0.002 | 0.837 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | ||

| FIRM | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.380*** | 0.347*** | ||

- This table examines whether abnormal related-party sales have positive or negative impacts on firm value for different subsamples. In Panel A, we partition our total sample into two subsamples with large and small percentages of parent directors based on the median percentage. In Panel B, we partition our total sample into two subsamples with high and low government ownership based on its sample median. The regression equation is as follows:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively (two-tailed test). The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

In summary, we find that the market value of the firm is positively related to abnormal related-party sales transactions, especially for firms that are unlikely to be controlled or influenced by the parent company (i.e., firms with a low percentage of parent directors and those with low ownership concentration). Put differently, this positive relationship becomes weakened or disappears for firms with a high percentage of parent directors and with high concentrated ownership. Our findings are in line with the view that RPTs are generally used for better resource allocation, and to improve intragroup allocation efficiency (Khanna and Palepu, 2000). However, firms with significant influence from the parent company via director appointment (i.e., P_DIR_HIGHi,t) or via concentrated ownership (i.e., GOV_HIGHi,t) are more likely to use RPTs as a means to manage earnings or tunnel profits. As such, related-party sales do not add value to such firms. Stated another way, the market discounts the value of related-party sales transactions in an environment where controlling owners of affiliated firms (such as parent companies or the government) are likely to use such transactions as a means to divert resources for their own interest at the expenses of affiliated firms’ minority shareholders.

3.3 Influence of Corporate Tax Avoidance Incentives

Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics for three subsamples of firms with: (i) no change in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t; (ii) an increase in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t; and (iii) a decrease in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t. We find that ABN_RPTi,t has the mean range of 0.002 to 0.003 and the median range from −0.025 to −0.028 for the three subsamples. It implies that firms are likely to have similar amount of abnormal RPTs, irrespective of whether they are subject to a tax rate change or not.

| Variable | Column A No change on tax rates (n = 3,250) | Column B Tax rate increased (TAXIN=1, n = 726) | Column C Tax rate reduced (TAXDE=1, n = 544) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Std. D | Mean | Median | Std. D | Mean | Median | Std. D | |

| Qi,t | 0.198 | −0.112 | 1.553 | 0.056 | −0.215 | 1.092 | −0.014 | −0.212 | 0.919 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.002 | −0.028 | 0.156 | 0.003 | −0.025 | 0.159 | 0.003 | −0.025 | 0.146 |

| SIZEi,t | 21.462 | 21.343 | 1.106 | 21.489 | 21.360 | 1.138 | 21.544 | 21.469 | 1.161 |

| AGEi,t | 1.978 | 2.079 | 0.551 | 2.027 | 2.197 | 0.619 | 2.216 | 2.303 | 0.407 |

| TAXi,t | 0.227 | 0.150 | 0.090 | 0.278 | 0.330 | 0.062 | 0.175 | 0.150 | 0.069 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.520 | 0.516 | 0.222 | 0.519 | 0.511 | 0.260 | 0.531 | 0.526 | 0.203 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.845 | 0.917 | 0.187 | 0.845 | 0.919 | 0.192 | 0.843 | 0.925 | 0.196 |

| BMi,t | 0.470 | 0.408 | 0.333 | 0.493 | 0.428 | 0.362 | 0.568 | 0.488 | 0.413 |

| ROAi,t | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.083 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.086 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.083 |

| BLOCKi,t | 17.836 | 15.135 | 13.253 | 15.943 | 12.450 | 12.411 | 16.269 | 13.655 | 11.908 |

- This table presents firms characteristics for three subsamples of firms with: (i) no change in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column A); (ii) an increase in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column B); and (iii) a decrease in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column C). Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1.

Table 8 shows the regression results of equation 4. We find that ABN_RPTi,t is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level, and the interaction terms, TAXINi,t*ABN_RPTi,t and TAXDEi,t*ABN_RPTi,t, are negative and significant at the 10 and 5 per cent levels, respectively. These results imply that the positive impact of related-party sales on firm value diminishes for firms that are subject to tax rate changes. Table 9 reports the results of regression in equation 1, separately, for the three partitioned tax-rate-change subsamples. As shown in Column A, firms that are not subject to any tax rate change have a positive association between abnormal related-party sales and firm value (where ABN_RPTi,t is positively significant at the 1 per cent level). The results are qualitatively similar to the main results as reported in Table 3. As presented in Columns B and C where firms are subject to a tax rate increase (TAXINi,t = 1) and a tax rate decrease (TAXDEi,t = 1), respectively, the coefficients on ABN_RPTi,t are also positive but are not statistically significant. Besides, we find that these coefficients (in Columns B and C) are smaller in magnitude than that reported in Column A (where firms are not subject to any tax rate change). In particular, the results of tests for differences in regression coefficients on ABN_RPTi,t between Columns A and B and between Columns A and C suggest that the differences are statistically significant at the 5 and 10 per cent levels (Z = 2.310 and Z = 1.920), respectively.

| Whole sample (n = 4,520) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-statistic |

| Intercept | 8.553 | 13.955*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.764 | 2.776*** |

| TAXINi,t* ABN_RPTi,t | −0.574 | −1.879* |

| TAXDEi,t* ABN_RPTi,t | −0.701 | −2.058** |

| TAXINi,t | −0.097 | −2.116** |

| TAXDEi,t | −0.121 | −2.536*** |

| SIZEi,t | −0.332 | −10.822*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.077 | 2.490*** |

| TAXi,t | 0.307 | 1.482 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.081 | −0.532 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.026 | 0.316 |

| BMi,t | −1.433 | −12.731*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.633 | 0.636 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.004 | 2.719*** |

| YEAR | Included | |

| FIRM | Included | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.292*** | |

- This table examines the impacts of corporate tax avoidance incentives on the association between abnormal related-party sales and firm value. The regression equation is as follows:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively (two-tailed test). The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

| Variable | Column A No change on tax rates (n = 3,250) | Column B Tax rate increased (TAXIN=1, n = 726) | Column C Tax rate reduced (TAXDE=1, n = 544) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-statistic | Coefficient | t-statistic | Coefficient | t-statistic | |

| Intercept | 9.084 | 11.449*** | 7.651 | 7.632*** | 5.280 | 5.792*** |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.755 | 2.759*** | 0.143 | 1.412 | 0.172 | 0.978 |

| SIZEi,t | −0.354 | −8.873*** | −0.300 | −5.627*** | −0.203 | −4.706*** |

| AGEi,t | 0.091 | 2.413** | 0.007 | 0.121 | 0.067 | 0.799 |

| TAXi,t | 0.322 | 1.312 | 0.491 | 0.992 | 0.183 | 0.325 |

| DEBTi,t | −0.178 | −0.975 | 0.307 | 0.969 | −0.393 | −1.543 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.095 | 0.881 | −0.077 | −0.549 | −0.180 | −1.021 |

| BMi,t | −1.615 | −12.087*** | −1.353 | −4.685*** | −1.068 | −4.997*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.424 | 0.311 | 1.013 | 1.312 | 1.360 | 1.593 |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.004 | 1.901* | 0.004 | 1.544 | 0.006 | 1.880* |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| FIRM | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.277*** | 0.433*** | 0.410*** | |||

- This table examines the association between Tobin's Q and related-party sales transactions for three subsamples of firms with: (i) no change in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column A); (ii) an increase in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column B); and (iii) a decrease in the statutory tax rate from year t–1 to year t (Column C). The regression equation is as follows:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively (two-tailed test). The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

In sum, we find that the positive impact of ABN_RPTi,t on firm value, as reflected by the positive coefficient on ABN_RPTi,t, decreases when firms experience a tax rate change. Our results in Tables 8 and 9 suggest that firms experiencing a tax rate increase are likely to make use of related-party sales transactions as a means for tax avoidance or planning activities. This in turn provides managers with an excuse for rent extraction activities such as tunneling profits out via related-party sales transactions (Desai et al., 2007). Similarly, firms experiencing a tax rate decrease are likely to use related-party sales transactions as an excuse for tax avoidance or planning activities and as a vehicle for propping up earnings to hide bad news and for covering up other earnings manipulations (Kim et al., 2011). Earnings manipulation deteriorates the quality of financial reporting, thereby exacerbating the information asymmetry between inside managers and outside investors. As a result, tax avoidance and planning activities have a negative impact on firm value. In our cases, the positive impact of ABN_RPTi,t on firm value is offset by the negative impact of tax planning for firms that are subject to a tax rate increase and decrease.15

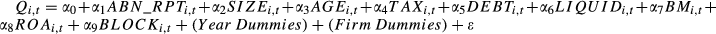

4 Further Tests

4.1 Stock Return and Related-party Sales Transactions

If the market views related-party sales transactions as value-adding activities, one can predict that stock market performance should be positively associated with the extent of a firm's involvement in related-party sales activities. To test this prediction, we now investigate the impacts of abnormal related-party sales on abnormal (excess) stock return. Specifically, we replace the dependent variable, Tobin's Q, in equation 1 by a firm's annual abnormal return, ARi,t, which represents a size-adjusted buy-and-hold stock return inclusive of dividends. To make sure that our measure of abnormal returns fully reflects information about a firm's operational performance in the current year, we measure annual stock return from the beginning of the fourth month of the current year to the end of the third month of the following year.

Table 10 reports the results of regression for this further test. As shown in Table 10, Panel A, we find that the coefficient on ABN_RPTi,t is positive and significant at the 10 per cent level. We also find that the coefficients on ABN_RPTi,t are significantly positive at the 1 and 5 per cent levels, respectively, for the subsamples of firms with low government ownership (Panel C) and of firms with no tax rate changes (Panel D). The above findings are similar to those using Tobin's Q as the dependent variable (as reported in Section 2.1). The only difference is that, as shown in Panel B of Table 10, the coefficient on abnormal related-party sales (ABN_RPTi,t) is not significant across the sample firms with a low percentage of parent directors, while in Panel B of Table 6, the ABN_RPTi,t coefficient is significantly positive for the same sample. In short, the results reported in Tables 3, 6, 9 and 10, taken together, indicate that the market views related-party sales as value-adding, particularly for firms with relatively less incentives for asset diversion via related-party sales transactions; however, for firms with relatively high incentives for asset diversion (i.e., firms with a high percentage of government ownership and/or with tax rate changes), the related-party sales transactions appear to be non-value-adding. This is because the positive impacts of related-party sales on firm valuation and/or stock return performance are offset by the negative impacts associated therewith (e.g., the use of related-party sales for tunneling assets for the interest of non-listed parent companies or controlling shareholders).

| Panel A: Whole sample (n = 4,520) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t-statistic |

| Intercept | −0.001 | −0.118 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.005 | 1.692* |

| SIZEi,t | 0.000 | 0.277 |

| AGEi,t | 0.001 | 0.811 |

| TAXi,t | −0.004 | −0.804 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.003 | 1.258 |

| LIQUIDi,t | −0.002 | −0.830 |

| BMi,t | −0.016 | −9.220* |

| ROAi,t | 0.057 | 7.917*** |

| BLOCKi,t | −0.001 | −0.754 |

| YEAR | Included | |

| FIRM | Included | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.069*** | |

| Panel B: Large vs. small percentage of parent directors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Large percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_HIGH; n = 944) | Small percentage of parent directors (P_DIR_LOW; n = 800) | ||

| Coeff. | t-stat. | Coeff. | t-stat. | |

| Intercept | 0.005 | 0.242 | −0.023 | −1.082 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.006 | 1.293 | 0.009 | 0.950 |

| SIZEi,t | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.997 |

| AGEi,t | −0.001 | −0.815 | 0.004 | 2.720*** |

| TAXi,t | −0.006 | −0.642 | −0.010 | −1.098 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.002 | 0.321 | 0.002 | 0.359 |

| LIQUIDi,t | −0.001 | −0.158 | −0.005 | −0.843 |

| BMi,t | −0.014 | −4.854*** | −0.016 | −3.987*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.051 | 3.635*** | 0.081 | 5.681*** |

| BLOCKi,t | 0.001 | 0.108 | −0.001 | −0.588 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | ||

| FIRM | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.063*** | 0.083*** | ||

| Panel C: High vs. low government ownership | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | High government ownership (GOV_HIGH; n = 1,664) | Low government ownership (GOV_LOW; n = 1,552) | ||

| Coeff. | t-stat. | Coeff. | t-stat. | |

| Intercept | −0.017 | −1.179 | −0.029 | −1.409 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | −0.002 | −0.523 | 0.013 | 2.171** |

| SIZEi,t | 0.001 | 1.003 | 0.002 | 1.701* |

| AGEi,t | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.000 | −0.311 |

| TAXi,t | −0.002 | −0.312 | 0.000 | 0.057 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.010 | 2.443** | −0.001 | −0.252 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.001 | 0.289 | 0.001 | 0.165 |

| BMi,t | −0.025 | −7.769*** | −0.017 | −5.320*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.065 | 4.688*** | 0.043 | 3.988*** |

| BLOCKi,t | −0.001 | −1.322 | −0.001 | −0.081 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | ||

| FIRM | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.074*** | 0.072*** | ||

| Panel D: No change on tax rates vs. tax rates increased or reduced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Column A | Column B | Column C | |||

| No change on tax rates (n = 3,250) | Tax rate increased (TAXIN=1, n = 726) | Tax rate reduced (TAXDE=1, n = 544) | ||||

| Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Intercept | 0.002 | 0.198 | −0.059 | −2.269** | 0.022 | 0.612 |

| ABN_RPTi,t | 0.008 | 2.222** | −0.010 | −1.419 | 0.005 | 0.759 |

| SIZEi,t | 0.000 | −0.474 | 0.002 | 1.999** | 0.001 | 0.606 |

| AGEi,t | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 1.957** | 0.001 | 0.026 |

| TAXi,t | 0.000 | 0.096 | 0.026 | 1.459 | −0.033 | −1.358 |

| DEBTi,t | 0.007 | 2.423** | −0.003 | −0.657 | −0.016 | −1.589 |

| LIQUIDi,t | 0.001 | 0.433 | −0.004 | −0.690 | −0.016 | −1.434 |

| BMi,t | −0.016 | −7.574*** | −0.018 | −5.117*** | −0.019 | −4.043*** |

| ROAi,t | 0.069 | 7.345*** | 0.041 | 3.446*** | 0.010 | 0.533 |

| BLOCKi,t | −0.001 | −0.127 | −0.001 | 0.689 | 0.000 | −3.061*** |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| FIRM | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.078*** | 0.062*** | 0.075*** | |||

- This table examines whether abnormal related-party sales have significant impacts on a firm's abnormal return. The regression equation is as follows:

- Definitions of all variables appear in Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively (two-tailed test). The t-statistics are based on standard errors adjusted for clustering on firms.

4.2 Sensitivity Tests

We conduct several additional tests to check the robustness of our regression results shown in Section 2.1. First, we replace the test variable in equation 1, ABN_RPTi,t, by RPTi,t. RPTi,t measures the total amount of related-party sales scaled by the total assets. Although not tabulated, for brevity, the results of regression using RPTi,t in lieu of ABN_RPTi,t are similar to those using ABN_RPTi,t (as reported in Table 3). Specifically, we find that the coefficient on RPTi,t is positive and significant below the 10 per cent level. The above results suggest that the valuation effect of related-party sales transactions holds, irrespective of whether the total (unadjusted) amount of RPTi,t or the abnormal (residual) amount of RPTi,t is used.

Second, as prior studies show that the government ownership through listed SOEs or asset management bureaus has differential impacts than those from the government ownership through unlisted SOEs, we exclude firms being owned by listed SOEs and state-asset investment bureaus from government-owned companies (Berkman et al., 2009, 2010) and rerun equation 1 for the subsamples with high/low government ownership. The results are qualitatively similar to the original results reported. Although nor reported for brevity, we find that the coefficients on ABN_RPTi,t are positively significant for the subsample with a low percentage of government ownership, and not significant for the subsample with a high percentage of government ownership. We also include GOV_LOWi,t (P_DIR_LOWi,t) in equation 1 as a control variable when analyzing the subsamples of parent-director ownership (government ownership). Untabulated results further show that the coefficient on ABN_RPTi,t remains positively significant for the subsamples with a low percentage of parent directors and government ownership, whereas the coefficients on GOV_LOWi,t and P_DIR_LOWi,t are insignificant. That means that the inclusion of the additional variables does not alter our statistical inferences on the variables of interest.

Third, we reclassify the subsamples of firms with a large and small percentage of parent directors and those with high and low government ownerships, using different classification methods. Specifically, a firm is classified as having a large (small) percentage of parent directors if its percentage of parent directors is above (below) the median in the current year (instead of all the years during the sample period). Similarly, a firm is classified as having high (low) government ownership if its government ownership is above (below) the median in the current year. We find that the regression results using these newly constructed subsamples are similar to those reported in Table 6: The coefficients on ABN_RPTi,t are positively significant only for the subsamples with a small percentage of parent directors and low government ownership.

Finally, Lo et al. (2010a) find that firms with a board with a high percentage of independent directors show a smaller magnitude of manipulated transfer prices for RPTs. We thus control for the possible effects of this type of director on the value of related-party sales by adding IND_DIRi,t (expressed as the percentage of independent directors) as an additional control variable. Untabulated results show that the coefficient on IND_DIRi,t is insignificant, suggesting that the inclusion of this variable does not alter our statistical inferences on the variables of interest.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we investigate the impact of abnormal related-party sales transactions on firm valuation captured by industry-adjusted Tobin's Q. Further, we also examine whether and how two aspects of influence of controlling shareholders, namely the percentages of parent directors and government ownership, matter in determining the relation between related-party sales transactions and firm value. The results, using a sample of Chinese listed firms, show that related-party sales transactions have a significantly positive impact on firm value in general. However, this positive impact of related-party sales on firm value is less prominent for firms with a large percentage of parent directors on board than for firms with a small percentage of parent directors. We also find that the positive impact of related-party sales on firm value disappears for firms with high government ownership, while it remains significant for firms with low government ownership.

Our results provide useful insights into whether and how the control power and incentive structure of controlling shareholders, captured by their ownership and parent directorship, affect the impact of related-party sales on firm value. Specifically, related-party sales transactions are value-adding to the extent that the transactions improve the efficiency of internal resource allocation among affiliated firms within the same corporate group. However, this value-adding effect is mitigated or offset in an environment where controlling shareholders of affiliated firms, such as unlisted parent companies or the government, exercise their control against the interest of affiliated firms.

We also find that even though abnormal related-party sales had a positive impact on firm value, this positive impact was offset by the associated negative impact when corporate insiders, such as controlling shareholders or corporate executives, have incentives to use RPTs as a tax planning tool in response to tax rate changes. These results lend further support to the view that corporate tax avoidance and planning activities are used as an excuse for managerial opportunism such as accrual management and as a vehicle for tunneling or resource diversion, rather than as an opportunity for pure tax savings and profit maximizing activities. The results suggest that outside investors or minority shareholders should look into the details of tax avoidance and planning activities to see whether these activities are used to cover up any earnings manipulation or tunneling activities. Given the scarcity of empirical evidence on the economic consequences of RPTs, we recommend further research on how RPTs can influence a firm's operational performance, firm valuation, and stock return.

Notes