The Client's Goals Are My Primary Responsibility: A Qualitative Study Examining Dietitians' Perceptions of the Barriers and Facilitators to Incorporating Environmentally Sustainable Food Systems in Clinical and Food Services Practice Within Healthcare Settings

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Current industrial food systems are not sustainable; they threaten future generations and cause rapid environmental degradation. Shifts to more sustainable food systems (SFS) and associated dietary practices can help reduce the carbon footprint and promote environmental sustainability. Dietitians working in healthcare settings can promote SFS initiatives. This study explored dietitians' SFS practices and their perceptions of the barriers and facilitators within healthcare settings.

Methods

This study analyzed secondary data from a survey of dietitians in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and the United States (US). A convenience sample of dietitians was recruited through national dietetic associations, professional networks, social media, listservs and snowball sampling. Responses were isolated for dietitians working in clinical and food services practice areas and analyzed thematically. The socio-ecological framework was used to understand areas where dietitians have influence within healthcare settings.

Results

Three main themes were identified where clinical and food services dietitians (n = 111) are incorporating SFS into practice in healthcare settings: education, communication, and workplace-related activities. Key barriers included operational and organizational factors (competing priorities), external factors (rising food costs), practice area constraints (limited role clarity), and concern for the client-practitioner relationship (CPR). The CPR tension theme emerged as a challenge for clinical dietitians in incorporating SFS into patient counselling. Facilitators included organizational factors (leadership), research and educational resources, personal factors (interest), and practical tools and resources (national food guides).

Conclusion

This study underscores the important work that dietitians are already doing across countries with different yet comparable dietetic professions and health systems. Recognizing that the barriers and facilitators identified in this study will vary between nations, institutions and practitioners, four areas of consideration were suggested, including expanding the client-practitioner relationship to include planetary health; learning from what dietetics and nutrition professionals are doing in other countries; advocating for policy and organizational changes within healthcare, and communicating in the ‘cost language’ of decision-makers. This study identified that there may be gaps for some dietitians in understanding client-centredness in the context of planetary health. This study highlights the need for further research to support more formalized approaches to the incorporation of SFS and planetary health considerations across all dietetic practice areas.

Summary

-

Dietitians play an important role in incorporating sustainable food systems (SFS) in healthcare settings. While barriers to incorporating SFS in healthcare settings were identified, dietitians have a strong and diverse skill set to support the incorporation of SFS into practice and are already doing this in a variety of ways. This paper provides insights and considerations for dietitians working in clinical and food services and showcases the activities, facilitators and barriers associated with incorporating SFS into healthcare settings.

-

Dietitians are encouraged to consider speaking the ‘cost language’ of decision makers in healthcare settings to positively frame SFS from a budget perspective.

-

Dietitians can incorporate SFS when providing nutritional care to clients by recognizing the interconnectedness between human and planetary health. Recommended strategies include utilizing motivational interviewing and behaviour change counselling techniques to incorporate SFS practices while maintaining a client-centred and planet-centred approach.

1 Introduction

How we eat, as a global population, must change to ensure the viability of future food systems [1]. Current industrial food systems are threatening future generations [2] and causing rapid environmental degradation [3]. Concerns with current food systems include their greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) levels, their impact on chronic disease prevalence, and excessive food waste [1]. More sustainable food systems and dietary patterns are needed. Sustainable food systems (SFS) are defined as “food system[s] that ensure food security and nutrition for all in such a way that the economic, social, and environmental bases to generate food security and nutrition of future generations are not compromised.” [4]. Environmentally sustainable diets are aligned with SFS with a focus on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and nuts while limiting red meat, sugar, and processed foods [2]. Dietary practices promoting sustainability include reducing food waste and associated plastic packaging, emphasizing plant-based foods, and prioritizing seasonal local foods [2].1

Globally, countries are urged to reduce GHGE to align with sustainable development goals [5] and support planetary health [6]. The healthcare sector contributes to 4.4% of overall GHGE, which is the equivalent of 514 coal-fired power plants annually [7]. Significant contributors to GHGE in healthcare include the production, transport, and disposal of food and agricultural products, medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and equipment [7]. In response, concepts like ‘planetary healthcare’ and the ‘greening of healthcare’, albeit not new concepts, have gained traction over decades as the urgency of the climate crisis becomes more apparent [8, 9]. Promoting sustainable food environments and dietary practices in healthcare settings has the potential to reduce the carbon footprint and promote environmental sustainability [5].

Clinical and food services dietitians work across various areas in healthcare settings and possess diverse skill sets, from providing individual patient care to participating in broader organizational initiatives. In hospitals, clinical dietitians provide education on diets for specific health conditions and ensure patients receive safe and appropriate meals. Food services dietitians plan patient menus, work with suppliers, and oversee operations, including staffing, budgets, and food safety [10]. Dietitians also work closely with other health professionals, where there are opportunities to promote SFS within healthcare settings [11, 12] and can provide important insights into the challenges and opportunities of incorporating sustainable food practices in healthcare settings. Clinical and food services dietitians can promote SFS in many ways, including introducing plant-based and locally sourced foods into hospital menus and reducing food and packaging waste [13-17].

Despite successfully incorporating SFS into practice activities, there is a need and potential for more. For example, Carino et al. [18] describe a novel SFS dietitian role in patient food services, noting that a lack of designated personnel and necessary skills and knowledge are barriers to SFS in healthcare settings. In addition, clinical dietitians can devise nutrition care plans supporting planetary health, and food service dietitians can work with suppliers to promote sustainable supply chains [19]. Although many strategies for incorporating SFS into clinical and food services dietetic practice have been identified [18, 19], research is needed to understand current practice, including the barriers and facilitators of incorporating SFS in healthcare settings. Further, examining what dietitians are doing across countries with different yet comparable health systems and dietetic professions could provide insight into contextual differences affecting practice. Thus, this study explored how clinical and food services dietitians across four countries incorporate SFS into their practice and their perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to doing so in healthcare settings.

2 Methods

Secondary data from a survey of dietitians (n = 219) in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and the United States (US) was used to address this study's aims. The survey was launched between 2022 and 2023 as part of a larger Canadian-led international study [20]. Ethics approval was received from all three universities affiliated with the primary research team; Toronto Metropolitan University (REB 2022-367), Acadia University (REB 22-42), and St. Francis Xavier University (File #25723). A convenience sample of dietitians was recruited through national dietetic associations, professional networks, social media, listservs and snowball sampling. The original study design and sampling method were not designed to elicit a representative sample of dietitians but aimed to recruit those incorporating SFS in their practice. An identical survey consisting of demographic and SFS-related questions (open- and closed-ended), hosted on QualtricsTM software, was circulated in each country. Minor differences in language and dietetic practice areas were adjusted for. For this study, only responses from dietitians who identified that they worked in clinical nutrition and/or food and nutrition management (food services) were included. The results of three open-ended survey questions related to incorporating SFS into practice, barriers, and supports were analyzed thematically.

Data were cleaned, deidentified and saved in Microsoft Excel. Responses were removed if they contained demographic information only (Canada) or if less than 50% of the survey was completed (US, UK, Australia). All respondents were assigned a unique participant number and country code and the spreadsheets were organized by country. Country-level data were imported into NVIVO to facilitate data management and analysis. The data were analyzed thematically by two members of the research team (K.S. and J.W.) following the methods outlined by Braun & Clarke [21], including (i) initial line-by-line coding for more extended responses; (ii) ongoing refinement of the codes after each country analysis, including collapsing and grouping codes and generating into themes; and (iii) ongoing discussion and deliberation of codes and themes among the research team to increase qualitative rigour. Any discrepancies were resolved by referring to the quotes and deliberating among team members to ensure the data were interpreted accurately. Google Jamboard was used to visualize themes during data analysis.

Responses from dietitians in clinical and food services were analyzed together for each country (i.e., they were not treated as two unique data sets). Therefore, the themes identified through analysis are shared across clinical and food services. Where possible, the researchers used contextual details within dietitians' responses to highlight any differences between practice areas. Themes were organized using the socio-ecological framework (SEF) [22], which has been applied in nutrition research to understand behavioural influences and potential leverage points–actions that have a larger impact than their immediate outcome - for health professionals [22, 23]. For this study, the SEF was used to understand the areas where clinical and food service dietitians have an influence in incorporating SFS into practice and to conceptualize the perceived barriers and facilitators. Activities were organized according to how dietitians are incorporating SFS into practice with consideration to leverage points at the individual (i.e., personal knowledge, skill and motivation), social (i.e., relationships with colleagues, administration and community members), physical (e.g., healthcare settings within the community); and the macro-environmental levels (e.g., national policy and marketing strategies).

3 Results

The analyses were based on the responses from one hundred and eleven dietitians working in clinical and food services in healthcare settings across four countries. The majority of dietitians were from Canada (41%) and the UK (35%), with fewer from Australia (15%) and the US (8%). A significantly larger number of dietitians were working in clinical (81%) compared to food services (19%), which was consistent across all countries (see Table 1 below).

| Canada | United Kingdom | Australia | United States | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 46 (41%) | 39 (35%) | 17 (15%) | 9 (8%) | 111 |

| Dietitians in clinical practice | 35 (76%) | 36 (92%) | 13 (76%) | 6 (66%) | 90 (81%) |

| Dietitians in food services | 11 (24%) | 3 (8%) | 4 (24%) | 3 (33%) | 21 (19%) |

3.1 Incorporating Sustainable Food Systems Into Practice in Healthcare Settings

Clinical and food services dietitians in healthcare settings are incorporating SFS into practice through education, communication, and workplace-related activities specific to their practice area (see Table 2). Through education, they are learning about SFS through tertiary education, continuing professional development, self-led study, and research. These dietitians share information through education activities with peers, colleagues, staff, and clients through client-centred education and counselling. For clinical dietitians, client education is focused on plant-based diets, the connection between healthy and sustainable diets, and methods to reduce household food waste. A unique example of education with clinical relevance included instructing clients on food-safe ways to freeze and cook with leftover oral nutrition supplements to reduce food waste. Using a variety of communication strategies, clinical and food services dietitians are also strategically raising awareness through activities such as Earth Day and advocating for changes in institutional food procurement practices.

| Theme | Key action area | Specific activities | Level of the socioecological framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Self and peer education | Educating self and others: Studying higher education, reviewing literature, peer and staff education, SFS in courses taught at university, continuing professional development |

Individual level; social environment |

| Research | Conducting research, e.g., conducting research in medical nutrition therapy and SFS | Individual level; social environment | |

| Client education | Client-centred education and counselling: Education focused on: plant-based/sustainable diets, connection between healthy diets and sustainable diets, reducing food waste, considering budget/savings in SFS recommendations, grocery shopping alignment with SFS, recycling, food storage tips, discussing freezing/cooking with leftover oral nutrition supplements in a food safe way (i.e. making ice blocks) to reduce waste, incorporating more plant-based options in diet sheets and advice where appropriate/evidence-based |

Individual level; social environment | |

| Communication | Resourceful promotion of SFS | Sustainable food marketing, using days of significance to bring awareness of SFS, promoting SFS through print and media | Macro-level environment |

| Advocacy | Requesting changes to the sustainability of enteral feed products to companies, raising awareness through partnerships, talking to decision makers to try and influence the system | Macro-level environment, social environment | |

| Workplace Activities | Institutional food service considerations | Sustainability-focused food service-related practices: Reducing food waste, local foods procurement, food services menu incorporates SFS, considering products or packaging, patient menus provide information on SFS |

Physical environment |

| Clinical approaches | Reducing waste in enteral nutrition prescriptions (formulating regimens that don't leave unused portions of feed in the bags), advocating for plant-based diet codes in institutions | Physical environment | |

| Collaboration | Networking and partnership development, sustainability groups, working group with food producers and procurement | Social environment | |

| Incorporation of SFS into strategy | Including a sustainability focus in policy and programs, strategy creation | Physical environment |

Dietitians also incorporated SFS into practice through workplace-related activities specific to their practice area. For food services dietitians, activities focused on the food environment and included reducing food waste, promoting local food procurement, incorporating sustainable menu considerations (e.g., sustainable foods and relevant information about SFS), and reducing packaging. For clinical dietitians, activities included formulating regimens that prevent leftover enteral nutrition formulas, recycling nutritional supplement bottles, and advocating for plant-based diet codes in healthcare institutions. Both groups of participants highlighted the need for collaboration and organizational policy change, such as collaborating with others through sustainability groups, partnerships with local food producers, and embedding sustainability within policies and programs.

3.2 Perceived Barriers in Healthcare Settings

Barriers identified by dietitians were themed into categories based on how frequently they were mentioned. There were four key barriers to incorporating SFS more widely into practice. Despite the ability to incorporate SFS through education, communication, and workplace-related activities, dietitians described barriers that were perceived to hinder progress in healthcare settings. Organizational and operational barriers (workplace-related), external factors, practice area constraints, and the client-practitioner relationship were identified. Table 3 includes a summary of key identified barriers, a description, and supporting quotes from participants.

| Barrier | Description | Examples of relevant quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace barriers (organizational factors) | Relate to the organization's vision and values and include policies, budgets, and leadership. | “I recommended [that] my workplace not purchase mini containers of items and [to] choose the larger food items for less plastic waste. My option was more affordable, but they said it was less convenient for the client to portion out the product from the larger container” (CP6) “Often these [SFS practices] have a cost attached to implement[ing] them (e.g., new lower carbon equipment) and right now with food production costs so high, there is no available money to invest” (UKP39). “In the hospital, [we are] trying to find the lowest cost foods rather than [focusing on] sustainability” (UKP11). |

| Workplace barriers (operational factors) | Relate to operations; procedural in nature and include the assignment of tasks and activities, dietitians’ influence within the organization, and perceptions of the healthcare setting itself | “There are some pockets of Veteran's Administration Nutrition Service[s] implementing more sustainable practices, but [these are] not [implemented] at my facility” (USP1) “[It is] impossible to source appropriate enteral and parental nutrition products” (UKP8) “Infection control precautions [are] trumping opportunities for sustainable initiatives.” (CAP21) “No control over hospital foods/menus” (CAP15) “[I am] not included with managing the sustainability of meals provided in the hospital. [The] catering team manage this” (UKP11) “Encouraged to use local foods on [the] menu, but [there is] no appetite to include these within state-wide contracts [n]or recognition for additional costs involved (associated with change process)” (AUP5) |

| External factors | Social, environmental and political influences outside the control of dietitians e.g., lack of government policy, corporate food interest and food cost, and geographical barriers | “Companies we rely on to supply products are slow to engage” (UKP8) “Seasonal variety of locally produced food [is] limited during winter months” (UKP3) “Corporations are looking for low-cost box-ticking solutions which limit how effective I can be” (UKP29) “The government must help in this issue” (CAP16) “I feel governments need to be more proactive, e.g., act on National Food Strategy” (UKP37) “I think many people are too busy focusing on their day job and don't realize that sustainability is part of everyone's role in the food industry” (UKP39) |

| Practice area constraints | Factors specific to clinical and food services practice areas, including a lack of professional role clarity and understanding of SFS in clinical practice, limited opportunities to collaborate between clinical and food services dietitians and lack of clinically relevant resources | “Certain issues [are] not relevant to clinical conversations” and “[there is] difficulty defining what “sustainable” really signifies in terms of food choices” (CAP23) Another dietitian pointed to a lack of SFS awareness within the profession: “I feel this may be more of a lack of awareness around a common language/vision when it comes to sustainable food systems” (CAP13) “Certain issues [are] not relevant to clinical conversations” (CAP13) “For clinical dietitians not directly working in food procurement, this still has some work [to do] to define and advocate.” (AUP12) “I've met many dietitians who define their practice area very narrowly and get uncomfortable engaging with new areas of practice…sustainability being one of them” (USP1). “[there is] no great consolidated resource to keep up to date, except maybe [the] ICDA SFS toolkit” (CAP23) |

| Concern for the client-practitioner relationship | Personal tensions associated with maintaining client-centredness when incorporating SFS into practice within client care | “It [SFS] is within the scope of dietetic practice but not at the expense of clinical outcomes or the patient feeling [like] I [don't] understand their food preferences [or] building rapport” (UKP3). “The client's agenda (goals) are my primary responsibility” (USP2) “Patients care more about food costs versus sustainability” (CAP34) “Yes, I feel in clinical dietetics the focus is on the patient's health and financial capacity rather than SFS” (AUP12) |

3.3 Physical Environment: Organizational and Operational Workplace Barriers

The most frequently reported barriers to incorporating SFS into practice are related to factors within the healthcare setting (35 mentions) that are organizational or operational. Organizational factors relate to the organization's vision and values, including policies, budgets, and leadership. Dietitians described several examples of organizational factors needed to incorporate SFS more widely into practice. These included policies and practices to support SFS, multi-disciplinary training for sustainability-related work, and supportive leadership in the workplace. One dietitian described a scenario where organizational factors prevented a more sustainable and cost-effective change in practice. Difficulties meeting institutional budget requirements while achieving SFS-friendly practices resulted from a lack of investment in sustainable practices and may signal a misalignment between organizational values and policies, as noted in Table 3 by Participant 11 from the UK.

Dietitians also identified operational factors as a perceived workplace barrier to incorporating SFS in practice. In contrast to organizational barriers, operational factors are procedural, including time and task management, food procurement processes, and other factors hindering SFS action within the physical setting. Dietitians described barriers in their assignment of tasks and activities, influence within the organization, and the healthcare setting itself. Specifically, examples included the perception that clinical and food services dietitians lack allocated time for SFS-related activities, have little influence over procurement decisions, face multi-system complexity in their work, and operate with varying levels of support for SFS activity across sites within the same organization (as noted by USP1 in Table 3). Concerning organizational influence, dietitians expressed frustration with their perceived limited ability to affect food availability and procurement processes within their institution. Similarly, dietitians also noted that operational practices prioritizing infection and food safety over sustainability, an operational precaution reinforced by the complexity of working in multiple systems, limited the broader incorporation of SFS within healthcare settings, particularly affecting food waste reduction (this was noted by CAP 21 in Table 3).

Specific barriers, such as having limited influence over operational activities, were uniquely identified by clinical dietitians who noted having limited influence over food services operations within their organizations. Differences among clinical and food services dietitians in their activities, tasks and influence over organizational and operational practices point to potential silos in some healthcare settings that may hinder collaboration between nutrition and food services departments and challenge efforts to incorporate SFS more widely into practice.

3.4 Macro Level Environment: External Factors Outside Dietitians' Influence

Following organizational and operational barriers, dietitians most frequently identified external factors as a challenge to incorporating SFS into practice (22 mentions). External factors were described as social, environmental and political influences outside the control of dietitians, and examples included a perceived lack of government policy, corporate food interest and food cost, and geographical barriers (e.g., food availability due to seasonal or geographical limitations) (see Table 3).

Dietitians described the need for government-level interventions, including but not limited to policies, that could influence the implementation of SFS practices within healthcare organizations (as CAP16 and UKP37 suggest, see Table 3).

Corporate food interests were also a source of concern and frustration, affecting their ability to incorporate sustainability into practice. Examples related to the widespread availability of ultra-processed foods, the food industry's preoccupation with cost, and limited attention to sustainability within some businesses.

3.5 Social Environment: Practice Area Constraints

Clinical and food services dietitians identified a third barrier related to practice area constraints (20 mentions). Practice area constraints specific to clinical practice included a lack of professional role clarity and understanding of SFS in clinical practice, a perceived separation from the activities of food services dietitians (possible silos/limited opportunities to collaborate) and a lack of clinically relevant resources and education to incorporate SFS into practice. Notably, the latter finding was a more common complaint among Canadian dietitians but present across all countries.

Dietitians described uncertainty in how best to incorporate SFS. The responses suggested SFS language confusion, a lack of clarity regarding SFS, and uncertainty around ‘what to do’. Compared to food services, slower uptake within clinical practice was also noted. While it was believed that the SFS profile was increasing among clinical dietitians, several respondents felt there is “still some work [to do] to define and advocate” (AUP12), for change within clinical practice.

In addition to a lack of professional role clarity, dietitians described how the capacity for collective activity among colleagues was limited by gaps in SFS awareness, individuals being slow to engage, and resistance to change among dietitians preferring more traditional practice. This barrier was noted across all countries.

3.6 Individual Level: Concern for the Client-Practitioner Relationship

The value dietitians place on their relationship with their clients was noted as a barrier to incorporating SFS in clinical practice. Specifically, 19 clinical dietitians (21%) in this sample described concern for the client-practitioner relationship by emphasizing the importance of prioritizing client needs ahead of sustainability within their day-to-day activities. For example, dietitians acknowledged that they did not include SFS considerations in the nutrition care planning process if they felt it did not align with the client's personalized nutrition goals. Thus, concern for the client-practitioner relationship and its importance to an effective therapeutic alliance presents a perceived barrier for clinical dietitians trying to incorporate SFS into their work with clients. The following sentiment was from a UK dietitian, “It [SFS] is within the scope of dietetic practice but not at the expense of clinical outcomes or the patient feeling [like] I [don't] understand their food preferences or [at the expense of] building rapport” (UKP3).

3.7 Perceived Facilitators in Healthcare Settings

Dietitians also described several perceived supports. These included supportive organizational (workplace) factors, access to research and educational resources, personal factors, and access to practical tools and resources.

3.8 Physical Environment and Social Environment: Organizational Factors

Across all countries, dietitians most frequently reported organizational factors within their respective healthcare settings as supportive (28 mentions). Workplace groups and initiatives related to SFS, such as “green committees”, projects related to sustainability, sustainability working groups, a green ambassador scheme (in the UK), and a national sustainable diet education workgroup (in the US) were identified as facilitators. These groups and initiatives are an important way for dietitians to learn and provide opportunities for intra- and interorganizational collaboration to support the incorporation of SFS into practice. Colleagues, particularly a supportive manager, were also identified as essential organizational factors. Individuals within the organization who share values and beliefs about the importance of sustainability were perceived as critical for sustainability leadership and the allocation of time within a dietitian's schedule for SFS-related activities. Supportive organizational governance tools (within public and private institutions), such as institutional policies, were another organizational support.

3.9 Individual Level: Access to Research and Educational Resources and Personal Factors

Following organizational factors, dietitians most frequently identified access to research and educational resources as a factor in increasing knowledge and confidence in incorporating SFS into practice (21 mentions). Dietitians understood the need to identify and incorporate evidence-based research into practice. Having “access to evidence-based data” (USP1) was a support for incorporating SFS into nutrition care. Professional education opportunities were identified as supportive for increased awareness and access to relevant research; these included online learning, continuing professional development, webinars, conferences, and workshops. Dietitians referred explicitly to those available through national dietetic associations as supportive. For example, the British Dietetic Association's One Blue Dot campaign and a Dietitians Australia workshop were noted. Thirteen dietitians emphasized the importance of personal factors, including personal interest, awareness, beliefs, and SFS practices, as they supported their incorporation of SFS into practice (13 mentions). Clinical dietitians incorporated SFS into their practice by utilizing existing skills, including those related to patient counselling and assessment (where client openness is identified), teaching (e.g., food waste reduction, budgeting, grocery shopping, recycling, and the storage and preparation of food) and resource development. Food services dietitians also described applying personal skills to incorporate SFS into food services, including reducing food waste, procuring local foods, incorporating plant-based or lower-carbon items into menus, and selecting sustainable products and packaging within the organization.

For example, dietitians recognized personal beliefs as a motivation for incorporating SFS into practice and underscored the obligation to take responsibility for SFS within the dietetics profession (Table 4).

| Facilitator | Description | Examples of relevant quotes or identified resources |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational factors | Factors within the organization perceived as supports for incorporating SFS into practice: E.g., workplace groups and initiatives related to SFS, supportive colleagues, supportive organizational governance | “Having a sustainability group at work to discuss ideas and thoughts” (UKP8) “Supportive managers who have dedicated FTE towards supporting sustainable food services.” (AUP2) “…hugely reliant on a few key champions and a supportive CEO” (AUP5) |

| Access to research and educational resources | Access to available research on SFS and, for some, professional education opportunities and critical learning through formal university education to increase knowledge and confidence in incorporating SFS into practice. | “Self-research (webinars, reading papers, books, etc.) to become more knowledgeable to provide most up-to-date evidence to patients”(CAP23) |

| Personal factors | Personal interest, awareness, beliefs and SFS practices, as supporting their incorporation of SFS into practice | “General interest/care in sustainability, otherwise there's no motive” (CADP8) “Personal interest [in sustainable food systems]” (UKP13) |

| Access to practical tools and resources | Practical tools and resources to support the incorporation of sustainability considerations in patient contexts, such as during nutrition assessments and interventions. | Clinical: BDA One Blue Dot guidelines, BDA resources, DA workshop, planetary health collective, new Canada's food guide, WHO recommendations for pulses, Nutritics Carbon Footprint Calculator Food Services: Humane Society Forward Food Program, Physician's Committee for Responsible Medicine |

3.10 Individual Level and Macro-Level Environment: Access to Practical Tools and Resources

Lastly, clinical and food services dietitians identified access to practical tools and resources as a support for incorporating SFS into practice (nine mentions). Tools and resources were described as a way of justifying the incorporation of sustainability within the patient context, such as during nutrition assessments and care planning. Frequently identified tools and resources included national nutrition guidelines aligned with SFS (e.g., Canada's Food Guide and the UK's Eatwell Guide). Other examples were more specific to clinical practice and included practice guidelines with an SFS focus, including those used in renal and diabetes care. Others described using a carbon footprint calculator or cooking tips for pulses from the World Health Organization as part of client education. The latter was recognized as an important resource for dietitians supporting a higher protein intake from plant sources. An SFS approach to dietetic assessment was mentioned infrequently and included comments about the need for “appropriate prescribing” and considering social and environmental factors with patients. Public-facing campaigns that promote and raise awareness about local, seasonal, and more sustainable food were thought to facilitate more significant consideration of local foods within hospital food procurement, resulting in broader public interest in consuming foods grown closer to home.

4 Discussion

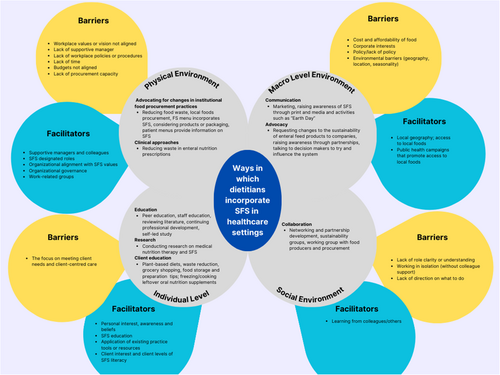

This study is an opportunity for dietitians to learn about SFS practices across four different countries with comparable health and dietetic professions. Dietitians are already incorporating SFS into practice in many ways, and there is an opportunity to do more. Yet, many dietitians experience personal (e.g., a lack of knowledge of SFS) and organizational barriers. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore how dietitians are incorporating SFS into healthcare settings and to identify the barriers and facilitators to doing so. As such, it offers a unique snapshot across four countries. Barriers included organizational and operational factors, factors external to dietetic remit, practice area constraints, and client-practitioner relationship concerns. These barriers emphasize the healthcare setting as an important influence. Facilitators included supportive organizational factors, access to research and educational resources, personal factors and access to practical tools and resources (see Figure 1). These supports emphasize the physical environment and professional associations as important influences.

From a socio-ecological perspective, these findings emphasize what is already known about the strong influence of the organizational setting (e.g., organizational policies) and the role of professional associations on dietitians’ incorporation of SFS into practice [13, 23-27]. However, this is the first study to provide specific details of the organizational barriers and supports.

One of the unexpected findings of this study was the concern dietitians across all four countries expressed for the client-practitioner relationship. The tension around maintaining client-centredness, a central feature in the therapeutic alliance between the client and the dietitian, suggests that, at present, many dietitians in healthcare settings consider the patient and planet separately and seek to prioritize only clients’ needs. There was an underlying sentiment that clinical dietitians should be treating the client, not the climate crisis. According to Singh & Sherman (2022), the growing influence of climate-related threats, such as food and water shortages, disease spread, and extreme weather events, presents an increasing risk to all individuals and strains the healthcare system [28]. Thus, we may be at a point where the inseparable relationship between human and ecological health, emphasized by nutrition and ecological scientists [4], cannot be ignored. Professional ethics (e.g., nonmaleficence or the principle of ‘do no harm’) requires us to reconsider clinical care and expand concern for clients to include the needs of the planet as well. Other dietitians are willing to address sustainability considerations in nutrition assessment, care and client education if they detect a higher level of food literacy or openness among clients. Reasons for these differences among dietitians could relate to client differences (assessed food literacy and receptiveness levels), uncertainty about incorporating SFS into patient care, and education and training. These factors can create variability in confidence when applying sustainable dietary patterns and their associated practices or when tailoring these to vulnerable client populations and disease states.

- 1.

Expand to a client-planet-practitioner relationship.

At the individual level, dietitians can make an informed, evidence-based decision to recognize the inseparable relationship between human health and the social and ecological systems upon which it depends. The Eat-Lancet Commission calls on healthcare professionals to promote the planetary health diet by assessing individual diets, providing dietary guidance, educating and training others, changing food procurement practices, and engaging in advocacy efforts within and around health professions [29]. Thus, clinical dietitians can expand their view of the client-practitioner relationship to include what is best for the health of the planet. Recognizing that sustainable diets are often synonymous with healthy eating recommendations, dietitians can use the language of healthy eating without explicitly talking about sustainable diets, to the same end. Landry and Ward (2024) note that patients are often open to adopting dietary changes when approached with a patient-centred strategy and gradual exposure [30]. In recommending plant-based diets, the authors suggest considering food preferences, cultural background, financial situation and eating habits and guiding clients in making simple changes [30]. These considerations are already standard practice for many clinical dietitians. However, the concept of incorporating SFS into the nutrition care planning process through ‘gradual exposure’ may be an important reminder to dietitians that, when expanding the client-practitioner relationship to include planetary health, they can choose whether and to what degree it is appropriate to provide education on the SFS co-benefits when recommending healthy dietary choices to clients. Another consideration for dietitians is to employ motivational interviewing and health behaviour change theories to help clients adopt SFS diets and associated practices [31, 32].

- 2.

Learn from other countries (or learn from others).

Within the social environment, dietitians interact with colleagues, professional associations, and community interest groups to share examples of SFS in practice, offer supportive ideas, and collectively shape new norms for SFS-supportive activities within the profession. Dietitians in this study identified their respective national dietetic associations (NDA) as a support for incorporating SFS into practice. Specifically, Dietitians Australia was recognized for a progressive Professional Code of Conduct [33], and British dietitians cited the One Blue Dot campaign [34], an initiative of the British Dietetics Association, as a critical source of evidence-based information on environmentally sustainable diets. Given that dietetics is an evidence-based profession, dietitians without access to a supportive professional environment and resources may be reluctant to incorporate SFS in practice. Wider incorporation of SFS into clinical practice may require dietitians to adapt by making greater use of emerging evidence. Boak and colleagues in Australia argue that the future dietetic workforce will require dietitians to be knowledge translators who can navigate the complexity of food and health systems and lead in systems change [35]. The willingness to embrace food systems and sustainability knowledge may be particularly relevant to clinical dietitians, given the prevailing view that clinical practice has seen a slower uptake in SFS relative to other practice areas.

Unconventional steps have been taken internationally to support and safeguard the SFS-related activities of food services dietitians. A novel Sustainable Food Systems Dietitian role in Melbourne, Australia, has been described [18]. Some tasks assigned to the SFS Dietitian include evaluating food waste, conducting needs assessments, raising awareness, and promoting local procurement [18]. This example offers a potential solution to the role clarity challenge identified by clinical dietitians in this study. A title such as SFS Clinical Practice Lead could promote ongoing SFS investment and action in clinical dietetics. A SFS Clinical Practice Lead might work collaboratively with their food services counterpart (possibly a SFS Food Services Practice Lead) to coordinate all food and nutrition-related activities within the healthcare setting. Depending on the size of the institution, this might include two distinct roles for dietitians or one combined role. This leadership is consistent with other research showing how supportive organizational changes, including supportive management, can shape social norms for acceptable and standard practice in healthcare settings [24, 26, 36]. These are novel examples of organizational practices occurring in some countries and institutions, providing insight into what is feasible, collectively and individually.

- 3.

Advocate for organizational changes within healthcare settings and sectors.

Consistent with recent research [13], dietitians in this study identified the need for organizational policies to support the incorporation of SFS in practice. However, there was a perception among some dietitians that they were ‘working in isolation’, and that their colleagues did not see SFS as a priority and that many preferred to maintain their traditional practice. Additionally, there was a lack of collaboration between dietitians in clinical and food services departments resulting from perceived organizational silos. Perceived silos may be linked to the organizational structures, roles and individual responsibilities within hospital food services and to the complexity of having outsourced food services in healthcare settings. Dietetic practice silos can also limit the influence of clinical dietitians in making hospital menu recommendations and promoting more sustainable food service practices in healthcare settings. Thus, this presents an opportunity for dietitians to advocate for policies that support the work of dietitians across previously perceived silos. Sustainability working groups and workplace projects were an avenue for collaborative work, a finding consistent with previous research [23]. Working groups facilitate networking and advocacy for sustainability-informed organizational policies concerning what is purchased, served, and recommended to patients within healthcare settings. In some institutions, dietitians can support wider acceptance of their SFS-related initiatives by aligning with existing sustainability plans and strategies and by linking this to their obligation as an employee within the organization.

To ensure success beyond the institution, Carino et al. [13] argue that public policy can help address the specific challenges that hospitals face. In this study, dietitians from the UK highlighted their country's ‘Net Zero’ as one such facilitator; the strategy is a series of policies and proposals for decarbonizing all sectors of the economy, including the health sector, by 2050 [37]. Specifically, the Strategy includes the creation of a recognized role for a Net Zero Dietitian tasked with delivering net zero food in hospitals, including reduced food waste, electronic meal ordering, lower carbon meal choices, and staff education on sustainable eating. Broader public policies that mandate SFS-promoting practices can facilitate the engagement of other allied health professionals and promote system-wide changes across the healthcare sector.

- 4.

Communicate effectively in the language of decision-makers.

Dietitians in this study echo previous research findings that cost is a significant operational barrier [38]. Dietitians noted that if SFS initiatives can save money, it can be helpful in getting it ‘over the line’ in contract purchasing decision making [39]. This suggests the power of communicating effectively in the language of decision-makers to gain support. Dietitians can draw on their training and expertise in communication to translate sustainability goals into the language of Group Purchasing Organizations (GPO) and procurement-related decisions. GPOs are large entities that help ensure that the food brought into healthcare facilities meets food safety regulations at an affordable price within budgets [38]. Dietitians can begin by investigating vendor contracts to better understand purchasing decisions in their healthcare organization. By investigating and understanding GPO contracts, dietitians may be better equipped with the language of decision-makers and more informed on the cost considerations of incorporating sustainable foods, products and services in healthcare settings [40].

Decision makers may also be focused on their organization's ability to be resilient in the face of disaster or to threats in access to supplies and services by global trade issues. Dietitians will need to be able to identify these concerns and tailor their messages accordingly to support ongoing SFS-related initiatives that can help organizations adapt under these circumstances. In this way, dietitians can contribute to not only sustainable, but resilient, healthcare.

4.1 Limitations

This study was limited to the perspectives of clinical and food services dietitians who were open to or already incorporating SFS into practice in four countries. Practice area categories differed across countries and collapsing these into broad practice areas may have limited analyses. For example, food services dietitians working in public institutions may perceive different barriers and supports than those working in the private sector. Further research is needed to understand what is needed to support those with limited SFS interest or training to consider SFS and planetary health goals within practice in healthcare settings.

5 Conclusion

Dietitians in clinical and food services can influence greater incorporation of SFS in healthcare settings through efforts at the individual (personal), social (networks), physical (setting), and macro-level (sector) environments. Recognizing that the barriers and facilitators identified in this study will vary between nations, institutions and practitioners, four areas of consideration were suggested, including expanding the client-practitioner relationship to include planetary health; learning from what dietetic and nutrition professionals are doing in other countries; advocating for policy and organizational changes within healthcare, and communicating in the ‘cost language’ of decision-makers. The client-practitioner relationship is a fundamental focus of dietetic practice. This study identified that there may be gaps for some dietitians in understanding client-centredness in the context of planetary health. This exploratory work calls for further research to understand how best to support those with specific health concerns and disease states in planetary health. This study also highlights the need for further research to support more formalized approaches to the incorporation of SFS and planetary health considerations across all dietetic practice areas.

Sustainable diets can be synonymous with healthy eating recommendations and align with emerging evidence for specific disease states. Given the urgency of the climate crisis, clinical and food services dietitians may be required to strengthen knowledge translation skills and act as ‘change agents’ [41] in their respective areas of practice to incorporate the planetary health diet and its associated practices in healthcare settings.

Author Contributions

Katy Saucis was involved in secondary data analysis, drafting and writing the full manuscript, and conceptualization of the paper. Jessica Wegener was involved in research generation, data collection, data analysis, conceptualization of the paper and full manuscript writing and editing. Liesel Carlsson was involved in research generation, data collection, drafting and editing the manuscript. Tracy Everitt was involved in research generation, data collection, and manuscript drafting and editing.

Acknowledgements

This study project was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Development Grant and a University Council for Research Award (St. Francis Xavier University).

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from all three universities affiliated with the primary research team between August 2022 and January 2023; Toronto Metropolitan University (REB 2022-367), Acadia University (REB 22-42) and St Francis Xavier University (Romeo #25723).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.