Do medical schools teach medical humanities? Review of curricula in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom

Abstract

Rationale and objectives

Medical humanities are becoming increasingly recognized as positively impacting medical education and medical practice. However, the extent of medical humanities teaching in medical schools is largely unknown. We reviewed medical school curricula in Canada, the UK and the US. We also explored the relationship between medical school ranking and the inclusion of medical humanities in the curricula.

Methods

We searched the curriculum websites of all accredited medical schools in Canada, the UK and the US to check which medical humanities topics were taught, and whether they were mandatory or optional. We then noted rankings both by Times Higher Education and U.S. News and World Report and calculated the average rank. We formally explored whether there was an association between average medical school ranking and medical humanities offerings using Spearman's correlation and inverse variance weighting meta-analysis.

Results

We identified 18 accredited medical school programmes in Canada, 41 in the UK, and 154 in the US. Of these, nine (56%) in Canada, 34 (73%) in the UK and 124 (80%) in the US offered at least one medical humanity that was not ethics. The most common medical humanities were medical humanities (unspecified), history, and literature (Canada); sociology and social medicine, medical humanities (unspecified), and art (UK); and medical humanities (unspecified), literature and history (US). Higher ranked medical schools appeared less likely to offer medical humanities.

Conclusions

The extent and content of medical humanities offerings at accredited medical schools in Canada, the UK and the US varies, and there appears to be an inverse relationship between medical school quality and medical humanities offerings. Our analysis was limited by the data provided on the Universities' websites. Given the potential for medical humanities to improve medical education and medical practice, opportunities to reduce this variation should be exploited.

1 INTRODUCTION

A growing number of studies have suggested that teaching medical humanities has a range of benefits1, 2 including better grades,3, 4 less burnout,5, 6 improved clinical judgement,7 better critical appraisal skills8 (including about wider problems such as overdiagnosis9) better prepared students for real life careers in medicine,10 enhanced medical professionalism,11 greater empathy,12 and appreciation that patients' problems go beyond their biology.13 The presence of elective courses in humanities is also appreciated by medical students.6, 14 Ethics is obviously required, since grasping the facts about a clinical case cannot guide action without considering patients' values (among other things).15 Reflecting the increasing importance in humanities, the Journal of the American Medical Association introduced a special section ‘Introducing the Arts and Medicine’ to their flagship journal in 2016.16

Teaching the medical humanities is now part of the core curriculum in many medical schools. For instance, the University of Toronto integrates consistent small-group reflection writing sessions, seminars on anti-oppression mediated through discussions of current news and social history, and historical backgrounds of medical topics like cancer into content modules. Moreover, the university offers many optional and complementary opportunities to integrate humanities, such as a health, arts, and humanities diploma program integrating literary narratives and art into medical knowledge.17 In the United Kingdom, King's College London has a mandatory series of philosophy lectures,18 and in the United States, Columbia University has a Division of Narrative Medicine which pervades the medical school teaching and includes literary theory, philosophy, narrative ethics and the creative arts.19

Given the potential benefits of studying medical humanities, it would be useful to know about the extent to which humanities are taught within medical schools. We are aware of one study that examined the prevalence of teaching medical humanities in Spain and Italy,20 but there are none in the United States or other English speaking countries. To overcome this gap, we used similar methods to survey whether medical humanities were part of the curricula in three English-speaking countries: Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

2 OBJECTIVES

Our primary objective was to survey medical school in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States to check whether and which medical humanities topics were taught. Our secondary objective was to explore the relationship inclusion of medical humanities in the curricula medical school ranking.

3 METHODS

3.1 Sample

We replicated the methods from a similar systematic search of medical schools in Spain and Italy.20 Our sample countries were chosen because they are broadly comparable in terms of language and cultural settings, and because of the location of the lead authors. A future larger study of all medical schools worldwide is planned.

3.2 Information sources

We identified accredited medical schools on July 15 2020 using Maclean's (Canada),21 the Medical Schools Council (United Kingdom),22 and the American Association of Medical Colleges (United States).23 The information on the medical curricula of each medical school was obtained from their institutional curriculum websites on the Internet. Where the same university offered more than one medical school programme (usually: an undergraduate and graduate programme in the UK), we included the one that was most comparable to the others in that country (usually: the undergraduate programme in the UK).

3.3 Eligibility criteria

To count as having included medical humanities, the curriculum website had to specify that there was an actual course (either optional or mandatory). It did not suffice to claim, for example, that cultural competence was a desired learning outcome. Again, following methods used in a previous survey, we considered humanities in a broad sense, which included literature, visual arts, performing arts, philosophy, anthropology, history and sociology.

3.4 Data items

Two authors for each country extracted the following data from the curricula website, where available: presence of subjects in humanities in the curriculum; whether specific medical humanities were taught (anthropology, history, language studies, literature, music, philosophy, religion and theology, sociology, visual arts and ‘other’); number of credits; academic consideration (compulsory or elective); academic year of the curriculum where the subject is offered (first to sixth); syllabus (presence or absence); ranking of the Medical School (see below).

We did not classify communication skills or foreign languages as humanities for the purposes of this study. This was to remain comparable with the previous study of medical humanities in Spain and Italy. We did not classify the study of population health, or social determinants of health as humanities, because they are social sciences. However, if the website classified sociology or medical sociology as a humanity, then we included it as such. This to follow the methods of the previous survey, and to be charitable as anecdotally, we have found that more traditional humanities topics are included in what is claimed to be sociology.

Within the UK, we did not classify Intercalated Degrees in the Medical Humanities as medical humanities courses. This is because intercalated degrees are additional, separate, degrees. Finally, we classified courses as compulsory even if they were sub-parts of other compulsory courses.

3.5 Obtaining an average rank

We used two rankings for medical schools: the Times Higher Education in the ‘clinical, pre-clinical, and health’ category24 and the U.S. News and World Report (USNWR) ranking.25 For both ranking systems, we extracted the within country ranking and the worldwide ranking. By using a UK-based and a US-based ranking system we aimed to overcome potential bias that the country producing the ranking system viewed its own medical schools as superior. For example, it may not have been an accident that the UK-based Times Higher Education system ranked Oxford as the best medical school in the world while the USNWR ranked Harvard as the best medical school in the world.

We then calculated the average rank. This was problematic for the schools that were listed in one of the systems but not the other. To overcome the problem, we assigned a rank to the unranked school based on its relative position in the system for which it was ranked. For example, in the US, Times Higher Education ranked 107 schools, and USNWR ranked 109. Say a school was ranked 51st by the former but not ranked by the latter. We would then assign it a rank of (51/109)107 = 49. Schools that were ranked by neither system were not included in any of our analyses related to rankings.

3.6 Analysis

We reported whether there was at least one humanities course taught other than ethics as a compulsory subject. This was because there was no consistent way of determining whether optional medical humanities were taken up by any students. We reported whether at least one medical humanity (other than ethics) was taught, whether or not it was mandatory and the total number of medical humanities offered (mandatory or not).

We explored whether there was a relationship between the ranking of the medical school programmes and whether they offered medical humanities in two ways

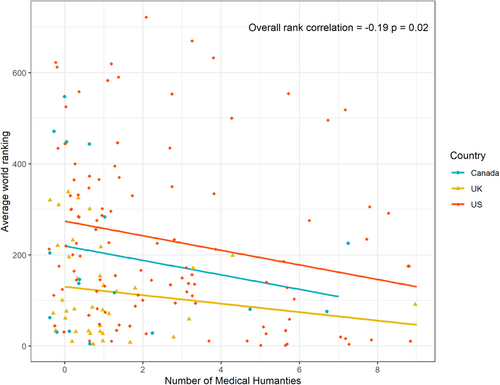

First, we explored whether there was a relationship between the number (mandatory or not) of medical humanities and the average world ranking. We quantified the strength of the relationship using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient for the three countries in turn (US, UK and Canada) and for all countries combined (Figure 1). Negative values for the correlation coefficients indicate an inverse association with average rankings being lower on average for schools with a greater number of humanities, whereas positive values would indicate rankings increasing with the number of humanities offered. Values close to zero be consistent with no association.

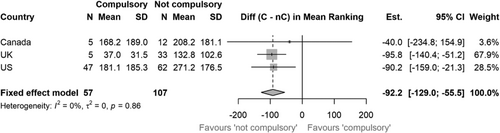

Second, we divided schools into two groups; those that mandated medical humanities (other than ethics) and those that did not. We estimated the average difference (95% CI) in mean ranking in non-compulsory schools and compulsory schools in the US, UK and Canada. Negative differences would indicate that the average mean ranking was higher in ‘non-compulsory’ schools and positive differences would indicate average mean ranking was higher in compulsory schools. Finally, we combined the three estimated differences to form an overall difference using a weighted average approach, where the weight were based on the reciprocal of the mean difference variance (inverse variance). This method allocates more weight to countries with more precise estimates. We did not include schools that were not ranked by either system in this analysis. Analysis was done using R 4.04 and the metafor library.

4 RESULTS

We were able to obtain data from 18 medical school programmes in Canada, 41 in the United Kingdom, and 154 in the United States. Of these, 17 in Canada, 38 in the United Kingdom, and 117 in the United States were ranked by at least one ranking system and we were able to ascertain the number of humanities and whether they were compulsory or not. Schools with missing data in one of these categories were excluded from the statistical analyses.

All our data was obtained from the websites. All the medical schools in Canada, all but nine in the United Kingdom, and all but 19 in the United States claimed to offer medical ethics as part of the curriculum. The 10 most highly ranked medical schools in the US all had at least one medical humanity that was compulsory (see Table 1). Not all the 10 most highly ranked medical schools in the UK or Canada required the teaching of at least one medical humanity.

| Name of School | Is at least one medical humanities topic (other than ethics) mandatory? | Total number of medical humanities other than ethics (mandatory or not) | Within country ranking (world ranking) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | |||

| University of Toronto | Yes | 1 | 1 (5) |

| McMaster University | Yes | 2 | 3 (29) |

| McGill University | No | 0 | 3 (31) |

| University of British Columbia | No | 0 | 4 (33) |

| University of Montreal | No | 0 | 5 (62) |

| University of Alberta | No | 7 | 7 (76) |

| University of Ottawa | Yes | 5 | 7 (81) |

| University of Calgary | No | 1 | 8 (117) |

| Western University | No | 0 | 9 (138) |

| Laval University | No | 0 | 9 (146) |

| United Kingdom | |||

| Oxford | Yes | 1 | 1 (4) |

| Imperial | No | 2 | 3 (8) |

| Cambridge | Yes | 1 | 3 (12) |

| UCL | No | 0 | 4 (10) |

| KCL | No/unsure | 3 | 5 (20) |

| Edinburgh | No/unsure | 1 | 6 (27) |

| Liverpool | Yes | 1 | 8 (71) |

| Glasgow | No | 1 | 9 (33) |

| Manchester | No | 0 | 9 (34) |

| Queen Mary | Unsure | 1 | 11 (45) |

| United States | |||

| Harvard | Yes | 5 | 1 (1.5) |

| Stanford | Yes | 7 | 3 (4) |

| Johns Hopkins | Yes | 6 | 3 (4.5) |

| Columbia | Yes | 9 | 7.5 (10.5) |

| UCLA | Yes | 1 | 7.5 (10.5) |

| University of Washington | Yes | 4 | 7.5 (11) |

| Yale | Yes | 5 | 8 (11) |

| Duke | Yes | 8 | 9 (13.5) |

| Michigan | Yes | 7 | 11.5 (16.5) |

| Washington University St. Louis | Yes | 7 | 13 (20) |

Excluding medical ethics, nine Canadian medical schools (56%) offered at least one medical humanity with six of these (33%) having the medical humanity as compulsory. Of the 34 UK, 30 (73%) offered at least one medical humanity and five (12%) had a medical humanity that was compulsory. One hundred and twenty-four (80%) US schools offered at least one medical humanity with 57 (37%) of these having the medical humanity as compulsory.

The most common medical humanities (see Table 2) were Unspecified Medical Humanities, History, and Literature (Canada), Sociology and Social Medicine, Unspecified Medical Humanities, and Art (UK), and Unspecified Medical Humanities, Literature and History (US).

| Canada | United Kingdom | United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | % of schools | Name | % of schools | Name | % of schools |

| Medical Humanities (unspecified) | 33% | Sociology and social medicine | 37% | Medical Humanities (unspecified) | 37% |

| History | 22% | Medical Humanities (unspecified) | 22% | Literature or narrative medicine | 32% |

| Literature or narrative medicine | 17% | Art (general or unspecified) | 12% | History | 23% |

| Visual arts | 17% | History | 10% | Art (general or unspecified) | 20% |

| Performing arts | 11% | Philosophy | 7% | Theology and spirituality | 15% |

| Art (general or unspecified) | 11% | Literature or narrative medicine | 7% | Sociology and social medicine | 15% |

We also found a weak statistically significant negative correlation between the number of medical humanities offered and the average ranking, with the average rank to be lower as the number of medical humanities topics offered increased (r = −0.19, P = 0.02), see Figure 1. This result was consistent in direction within country: UK schools (r = −0.09, P = 0.55), Canadian schools (r = −0.26, P = 0.31), US schools (r = −0.25, P = 0.007). Medical schools that had at least one medical humanity were ranked an average of 92.2 points lower than schools that did not list a compulsory medical humanity (95% CI −129.0 to −55.5, P < 0.0001) (see Figure 2).

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Summary of findings and implications for research and practice

Three quarters of the medical schools in the United States and the United Kingdom offered at least one medical humanity, and half of those in Canada did so. While high, this was not as prevalent as it was in medical schools in Spain and Italy.20 A third of the medical schools in the United States and Canada had compulsory medical humanities, and just over 10% of the medical schools in the UK mandated at least one medical humanity. Three medical humanities topics featured in the top 10 most common in all three countries: history, literature/narrative medicine and art.

Contrary to what we anticipated, there was an association between lower ranked schools and quantity of medical humanities (and whether the medical humanities were compulsory). This association is unlikely to be causal for a number of reasons, including a common cause. The higher-ranked medical schools may not feel the need to bolster their curricula with topics they believe (for better or worse) are not essential. Relatedly, the higher-ranked schools may not feel pressure to innovate and be steeped in tradition that makes curricular innovations difficult. Anecdotally, some of the authors have noted that the higher-ranked medical schools focus on the ‘harder’ aspects of the curriculum, and de-value the ‘softer’ aspects; these anecdotes cannot be generalized. The lower-ranked schools, by contrast, are often newer and could be more sensitive to the need to innovate or improve. It will be interesting to see whether this changes if teaching medical humanities becomes compulsory. Addressing this potential imbalance in medical humanities could be achieved in a cost-effective way as teaching medical humanities rarely requires equipment, and humanities teachers are rarely on (higher) clinical salaries.

Given the growing importance of teaching medical humanities, we propose that medical schools communicate their humanities offerings clearly on their curriculum websites. We also recommend that future research to investigate the effects of offering medical humanities, for example on burnout, subsequent medico-legal complaints, and effectiveness of practice (measured, e.g., by patient satisfaction, which is a determinant of outcomes26, 27). At least in principle, there could also be harms, for example by taking away students' attention from the basic science of medicine. It may also involve additional costs, although, as mentioned above, these are likely to be minimal. Related to the potential cost, future research should investigate the most efficient ways to introduce medical humanities to medical school curricula in ways that enhances rather than interferes with the other competing and necessary topics.

5.2 Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, we used the university medical school curriculum websites as our main sources, whereas the information on the website may not reflect what is actually taught. For example, Queens University (Canada) does not list medical humanities on their curriculum website (apart from ethics). Yet we are aware through the effort of their previous Chair of History of Medicine that Queens integrates mandatory history of medicine lectures into various curriculum segments.28 Gathering information from the website also made it difficult to know whether the humanities listed as being taught were taught in a superficial (e.g., as a one-off, short lecture) or deeper way (e.g., as a series of lectures).7 However, given the importance of websites for providing information about their curricula, we believe that it was not unreasonable to look at the curriculum websites. Second, the data extraction was not done by two independent authors. Third, we followed previous surveys and included some topics such as sociology which are often not considered to be humanities. We did this so our results could be comparable to related studies in Europe, and only when the medical schools classified sociology as a humanity. Fourth, we used a convenience sample, albeit one that that provides a useful basis for comparison due to shared culture and language. Fifth, the ranking systems were blunt tools for rating the quality of medical schools, as evidenced by the differences between the two ranking systems we used. Our averaging of the rankings mitigated this limitation to some degree. Sixth, in Canada, some of the material might be covered in residency training. It is worth nothing that it is a possibility (and might account for a lower rate of uptake in their undergraduate training programs). Finally, we did not investigate the relationship between specific medical humanities and the school rankings. This would be an appropriate question for future studies of the effects of teaching medical humanities to medical students to examine.

6 CONCLUSION

According to what they report on their curriculum websites, medical humanities are commonly offered in medical schools, at least as an option. Contrary to what we anticipated, there was an association between lower ranked schools and medical humanities teaching. Future research should investigate the effects of teaching medical humanities to medical students, and which medical humanities topics are most appreciated, appropriate, and effective.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have conflicts of interest related to this study.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

Jeremy Howick conceived of the idea, drafted the first manuscript and piloted the data extraction form. Dien Ho, Raffaella Campaner and Lunan Zhao further developed the structure of the study. Dien Ho, Lunan Zhao, Alessandro Rosa, Brenna McKaig did the data extraction. Jason Oke conceived of and conducted the statistical methods and analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and editing the final manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The full data for this study is available as a Supplementary file.